Five Forces Model

Based Upon Michael E. Porter’s Work

Contents

1

2

3

Michael Porter

1

1.1

Early life . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

1.2

Career . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

1.2.1

Competition among nations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

1.2.2

Healthcare . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.2.3

Consulting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.2.4

Non-profit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.3

Honors and awards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.4

Criticisms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.5

Works . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.6

See also . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

1.7

References

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

1.8

External links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

Porter five forces analysis

5

2.1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

2.1.1

Threat of new entrants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

2.1.2

Threat of substitute products or services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.1.3

Bargaining power of customers (buyers) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.1.4

Bargaining power of suppliers

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.1.5

Intensity of competitive rivalry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

2.2

Usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

2.3

Criticisms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

2.4

See also . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

2.5

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

2.6

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

Five forces

Porter’s generic strategies

9

3.1

Concept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

3.2

Origins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10

i

ii

4

5

CONTENTS

3.3

Cost Leadership Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10

3.4

Differentiation Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

3.4.1

Variants on the Differentiation Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

3.5

Focus strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

3.6

Recent developments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

3.7

Criticisms of generic strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

3.8

See also . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13

3.9

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13

Competitive advantage

14

4.1

Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

4.2

Generic competitive strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

4.2.1

Cost leadership strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

4.2.2

Differentiation strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

4.2.3

Innovation strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

4.2.4

Operational effectiveness strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

4.3

See also . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

4.4

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

4.5

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

4.6

External links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

Value chain

17

5.1

Firm-level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

5.1.1

Primary activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

5.1.2

Support activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

5.1.3

Physical, virtual and combined value chain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

5.2

Industry-level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

5.3

Global value chains (GVCs)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

5.3.1

Cross border / cross region value chains . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

5.3.2

Global value chains (GVCs) in development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

5.4

Significance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

5.5

Use with other Analysis Tools

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

5.6

SCOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

5.7

Value Reference Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

5.8

See also . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

5.9

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

5.10 Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

5.11 External links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

5.12 Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

CONTENTS

iii

5.12.1 Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

5.12.2 Images . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

5.12.3 Content license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

Chapter 1

Michael Porter

For the American wrestling ring announcer, see Michael inspired the Porter five forces analysis framework for anaPorter (professional wrestling). For the Australian rules lyzing industries.[3]

footballer, see Michael Porter (footballer). For the English

footballer, see Mick Porter.

Michael Eugene Porter (born May 23, 1947)[2] is the

Bishop William Lawrence University Professor at The Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, based at the Harvard

Business School. He is a leading authority on competitive

strategy and the competitiveness and economic development of nations, states, and regions. Michael Porter’s work

is recognized in many governments, corporations and academic circles globally. He chairs Harvard Business School’s

program dedicated for newly appointed CEOs of very large

corporations.

1.2

Career

Michael Porter is the author of 18 books and numerous

articles including Competitive Strategy, Competitive Advantage, Competitive Advantage of Nations, and On Competition. A six-time winner of the McKinsey Award for the

best Harvard Business Review article of the year, Professor

Porter is the most cited author in business and economics.[4]

Porter stated in a 2010 interview: “What I've come to see as

probably my greatest gift is the ability to take an extraordinarily complex, integrated, multidimensional problem and

get arms around it conceptually in a way that helps, that informs and empowers practitioners to actually do things.”[3]

1.1 Early life

Michael Eugene Porter received a BSE with high honors in

aerospace and mechanical engineering from Princeton University in 1969, where he graduated first in his class and was

1.2.1 Competition among nations

elected to Phi Beta Kappa and Tau Beta Pi. He received an

MBA with high distinction in 1971 from Harvard Business

School, where he was a George F. Baker Scholar, and a PhD Porter wrote “The Competitive Advantage of Nations” in

1990. The book is based on studies of ten nations and arin business economics from Harvard University in 1973.

gues that a key to national wealth and advantage was the

Porter said in an interview that he first became interested in productivity of firms and workers collectively, and that the

competition through sports. He was on the NCAA cham- national and regional environment supports that productivpionship golf squad at Princeton and also played football, ity. He proposed the “diamond” framework, a mutuallybaseball and basketball growing up.[3]

reinforcing system of four factors that determine national

Porter credits Harvard professor Roland “Chris” Chris- advantage: factor conditions; demand conditions; related

tensen with inspiring him and encouraging him to speak up or supporting industries; and firm strategy, structure and riduring class, hand-writing Porter a note that began: “Mr. valry. Information, incentives, and infrastructure were also

Porter, you have a lot to contribute in class and I hope you key to that productivity.[5]

will.” Porter reached the top of the class by the second year During April 2014, Porter discussed how the United States

at Harvard Business School.[3]

ranks relative to other countries on a comprehensive scoreAt Harvard, Porter took classes in industrial organization card called “The Social Progress Index”, an effort which he

economics, which attempts to model the effect of compet- co-authored.[6] This scorecard rated the U.S. on a compreitive forces on industries and their profitability. This study hensive set of metrics; overall, the U.S. placed 16th.[7]

1

2

CHAPTER 1. MICHAEL PORTER

1.2.2

Healthcare

1.2.4

Non-profit

foundations in the area of creating social value. He also

currently serves on the Board of Trustees of Princeton UniPorter has devoted considerable attention to understanding versity.

and addressing the pressing problems in health care delivery

in the United States and other countries. His book, Redefining Health Care (written with Elizabeth Teisberg), devel- 1.3 Honors and awards

ops a new strategic framework for transforming the value

delivered by the health care system, with implications for

In 2000, Michael Porter was appointed a Harvard Univerproviders, health plans, employers, and government, among

sity Professor, the highest professional recognition that can

other actors. The book received the James A. Hamilton

be awarded to a Harvard faculty member.[10] In 2009, he

award of the American College of Healthcare Executives

was awarded an honorary degree from McGill University.

in 2007 for book of the year. His New England Journal

of Medicine research article, “A Strategy for Health Care

Reform—Toward a Value-Based System” (July 2009), lays

out a health reform strategy for the U.S. His work on health 1.4 Criticisms

care is being extended to address the problems of health

care delivery in developing countries, in collaboration with Porter has been criticized by some academics for inconDr. Jim Yong Kim and the Harvard Medical School and sistent logical argument in his assertions.[11] Critics have

Harvard School of Public Health.

also labeled Porter’s conclusions as lacking in empirical

support and as justified with selective case studies. They

have also claimed that Porter fails to credit original cre1.2.3 Consulting

ators of his postulates originating from pure microeconomic

theory.[4][12][13][14] Others have argued Porter’s firm-level

In addition to his research, writing, and teaching, Porter analysis is widely misunderstood and mis-taught.[15]

serves as an advisor to business, government, and the social

sector. He has served as strategy advisor to numerous leading U.S. and international companies, including Caterpil1.5 Works

lar, Procter & Gamble,[8] Scotts Miracle-Gro, Royal Dutch

Shell, and Taiwan Semiconductor. Professor Porter serves

on two public boards of directors, Thermo Fisher Scientific Competitive Strategy

and Parametric Technology Corporation. Professor Porter

also plays an active role in U.S. economic policy with the

• Porter, M.E. (1979) “How Competitive Forces Shape

Executive Branch and Congress, and has led national ecoStrategy”, Harvard Business Review, March/April

nomic strategy programs in numerous countries. He is cur1979.

rently working with the presidents of Rwanda and South

• Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy, Free Press,

Korea.

New York, 1980. The book was voted the ninth most

Michael Porter is one of the founders of The Monitor

influential management book of the 20th century in

Group, a strategy consulting firm that came under scrutiny

a poll of the Fellows of the Academy of Managein 2011 for its past contracts with the Muammar Gaddafiment.[16]

led regime in Libya and alleged failure to register its activities under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. In 2013

• Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage, Free

Monitor was sold to Deloitte Consulting through a strucPress, New York, 1985.

tured bankruptcy proceeding.

• Porter, M.E. (ed.) (1986) Competition in Global Industries, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1986.

Michael Porter has founded three major non-profit organizations: Initiative for a Competitive Inner City – ICIC[9] in

1994, which addresses economic development in distressed

urban communities; the Center for Effective Philanthropy,

which creates rigorous tools for measuring foundation effectiveness; and FSG-Social Impact Advisors, a leading

non-profit strategy firm serving NGOs, corporations, and

• Porter, M.E. (1987) “From Competitive Advantage

to Corporate Strategy”, Harvard Business Review,

May/June 1987, pp 43–59.

• Porter, M.E. (1996) “What is Strategy”, Harvard Business Review, Nov/Dec 1996.

• Porter, M.E. (1998) On Competition, Boston: Harvard

Business School, 1998.

1.6. SEE ALSO

• Porter, M.E. (1990, 1998) “The Competitive Advantage of Nations”, Free Press, New York, 1990.

• Porter, M.E. (1991) “Towards a Dynamic Theory of

Strategy”, Strategic Management Journal, 12 (Winter

Special Issue), pp. 95–117. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

com/doi/10.1002/smj.4250121008/abstract

• McGahan, A.M. & Porter, M.E. Porter. (1997)

“How Much Does Industry Matter, Really?" Strategic

Management Journal, 18 (Summer Special Issue),

pp. 15–30. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.

1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199707)18:1%2B%3C15::

AID-SMJ916%3E3.0.CO;2-1/abstract

• Porter, M.E. (2001) “Strategy and the Internet”,

Harvard Business Review, March 2001, pp. 62–78.

3

• Rhatigan, Joseph, Sachin H Jain, Joia S. Mukherjee,

and Michael E. Porter. “Applying the Care Delivery

Value Chain: HIV/AIDS Care in Resource Poor Settings.” Harvard Business School Working Paper, No.

09-093, February 2009.

1.6

See also

• Cluster development

• Marketing strategies

• National Diamond

• Strategic planning

• Porter, M.E. & Kramer, M.R. (2006) “Strategy and

Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage

and Corporate Social Responsibility”, Harvard Business Review, December 2006, pp. 78–92.

• Strategic management

• Porter, M.E. (2008) “The Five Competitive Forces

That Shape Strategy”, Harvard Business Review, January 2008, pp. 79–93.

• Smart, Connected Products

• Porter, M.E. & Kramer, M.R. (2011) “Creating

Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review, Jan/Feb

2011, Vol. 89 Issue 1/2, pp 62–77

• Porter, M.E. & Heppelmann, J.E. (2014) “How Smart,

Connected Products are Transforming Competition”,

Harvard Business Review, November 2014, pp 65–88

Domestic Health Care

• Porter, M.E. & Teisberg, E.O. (2006) “Redefining

Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition On

Results”, Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

• Berwick, DM, Jain SH, and Porter ME. “Clinical Registries: The Opportunity For The Nation.” Health Affairs Blogs, May 2011.

• Social Progress Index

• Techno cluster

1.7

References

[1] http://hbr.org/2008/01/

the-five-competitive-forces-that-shape-strategy/ar/1

[2] date & year of birth, full name according to LCNAF CIP

data

[3] Kiechel, Walter (2010). The Lords of Strategy. Harvard

Business Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-782-3.

[4] False Expectations of Michael Porter’s Strategic Management Framework, by Omar AKTOUF, Dr. HEC Montréal

[5] Porter, Michael E. Porter (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Free Press. ISBN 0-684-84147-9.

[6] CNN-GPS with Fareed Zakaria-Michael Porter on GPS: Is

the U.S. #1? April 20, 2014

[7] Social Progress Imperative.Org - Retrieved May 2014

Global Health Care

[8] Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press.

• Jain SH, Weintraub R, Rhatigan J, Porter ME, Kim JY.

“Delivering Global Health”. Student British Medical [9] “Initiative for a Competitive Inner City”.

Journal 2008; 16:27.[1]

[10] Colvin, Geoff (October 29, 2012). “There’s No Quit in

Michael Porter”. Fortune 166 (7): 162–166.

• Kim JY, Rhatigan J, Jain SH, Weintraub R, Porter

ME. “From a declaration of values to the creation of [11] Sharp, Byron; Dawes, John (1996), “Is Differentiation Opvalue in global health: a report from Harvard Univertional? A Critique of Porter’s Generic Strategy Typology,”

sity’s Global Health Delivery Project”. Global Public

in Management, Marketing and the Competitive Process,

Peter Earl, Ed. London: Edward Elgar.

Health. 2010 Mar; 5(2):181-8.

4

CHAPTER 1. MICHAEL PORTER

[12] Speed, Richard J. (1989), “Oh Mr Porter! A Re-Appraisal

of Competitive Strategy,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 7 (5/6), 8–11.

[13] Yetton, Philip, Jane Craig, Jeremy Davis, and Fred Hilmer

(1992), “Are Diamonds a Country’s Best Friend? A Critique

of Porter’s Theory of National Competition as Applied to

Canada, New Zealand and Australia,” Australian Journal of

Management, 17 (No. 1, June), 89–120.

[14] Allio, Robert J. (1990), “Flaws in Porter’s Competitive Diamond?,” Planning Review, 18 (No. 5, September/October),

28–32.

[15] Spender, J.-C., & Kraaijenbrink, Jeroen. (2011). Why

Competitive Strategy Succeeds - and With Whom. In

Robert Huggins & Hiro Izushi (Eds.), Competition, Competitive Advantage, and Clusters: The Ideas of Michael

Porter (pp. 33-55). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[16] Bedeian, Arthur G.; Wren, Daniel A. (Winter 2001).

“Most Influential Management Books of the 20th Century” (PDF). Organizational Dynamics 29 (3): 221–225.

doi:10.1016/S0090-2616(01)00022-5.

1.8 External links

• Michael Porter currently leads the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness at Harvard Business School

– Accessed October 15, 2012

• Porter proposals for reforming the delivery of health

care – Accessed October 15, 2012

• Summary Biography from Global Leaders

• Biography at Harvard Business School Faculty Pages

– Accessed October 15, 2012

• Porter Prize

• Michael Porter’s Author profile and bibliography from

Shelfari – Accessed October 15, 2012

Chapter 2

Porter five forces analysis

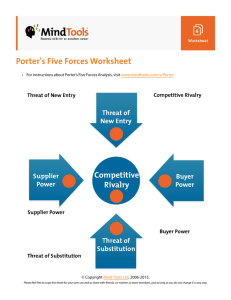

Threat

of New Entrants

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

have been able to make a return in excess of the industry

average.

Industry

Rivalry

Porter’s five forces include - three forces from 'horizontal' competition: the threat of substitute products or services, the threat of established rivals, and the threat of new

entrants; and two forces from 'vertical' competition: the

bargaining power of suppliers and the bargaining power of

customers.

Threat

of Substitutes

Porter developed his Five Forces analysis in reaction to

the then-popular SWOT analysis, which he found unrigorous and ad hoc.[1] Porter’s five forces is based on the

Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm in industrial orA graphical representation of Porter’s five forces

ganizational economics. It has been applied to a diverse

range of problems, from helping businesses become more

Porter five forces analysis is a framework that attempts profitable to helping governments stabilize industries.[2]

to analyze the level of competition within an industry and Other Porter strategic frameworks include the value chain

business strategy development. It draws upon industrial or- and the generic strategies.

ganization (IO) economics to derive five forces that determine the competitive intensity and therefore attractiveness

of an Industry. Attractiveness in this context refers to the

overall industry profitability. An “unattractive” industry is 2.1 Five forces

one in which the combination of these five forces acts to

drive down overall profitability. A very unattractive in- 2.1.1 Threat of new entrants

dustry would be one approaching “pure competition”, in

which available profits for all firms are driven to normal

Profitable markets that yield high returns will attract new

profit. This analysis is associated with its principal innovafirms. This results in many new entrants, which eventually

tor Michael E. Porter of Harvard University.

will decrease profitability for all firms in the industry. UnPorter referred to these forces as the micro environment, to less the entry of new firms can be blocked by incumbents

contrast it with the more general term macro environment. (which in business refers to the largest company in a cerThey consist of those forces close to a company that affect tain industry, for instance, in telecommunications, the tradiits ability to serve its customers and make a profit. A change tional phone company, typically called the “incumbent opin any of the forces normally requires a business unit to re- erator”), the abnormal profit rate will trend towards zero

assess the marketplace given the overall change in industry (perfect competition).

information. The overall industry attractiveness does not

The following factors can have an effect on how much of a

imply that every firm in the industry will return the same

threat new entrants may pose:

profitability. Firms are able to apply their core competencies, business model or network to achieve a profit above

the industry average. A clear example of this is the air• The existence of barriers to entry (patents, rights,

line industry. As an industry, profitability is low and yet

etc.). The most attractive segment is one in which enindividual companies, by applying unique business models,

try barriers are high and exit barriers are low. Few new

Bargaining Power of Buyers

5

6

CHAPTER 2. PORTER FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS

firms can enter and non-performing firms can exit eas- 2.1.3

ily.

• Government policy

Bargaining power of customers (buyers)

• Product differentiation

The bargaining power of customers is also described as the

market of outputs: the ability of customers to put the firm

under pressure, which also affects the customer’s sensitivity

to price changes. Firms can take measures to reduce buyer

power, such as implementing a loyalty program. The buyer

power is high if the buyer has many alternatives. The buyer

power is low if they act independently e.g. If a large number

of customers will act with each other and ask to make prices

low the company will have no other choice because of large

number of customers pressure.

• Brand equity

Potential factors:

• Capital requirements

• Absolute cost

• Cost disadvantages independent of size

• Economies of scale

• Economies of product differences

• Switching costs or sunk costs

• Expected retaliation

• Access to distribution

• Customer loyalty to established brands

• Industry profitability (the more profitable the industry

the more attractive it will be to new competitors)

2.1.2

Threat of substitute products or services

• Buyer concentration to firm concentration ratio

• Degree of dependency upon existing channels of distribution

• Bargaining leverage, particularly in industries with

high fixed costs

• Buyer switching costs relative to firm switching costs

• Buyer information availability

• Force down prices

• Availability of existing substitute products

The existence of products outside of the realm of the common product boundaries increases the propensity of cus• Buyer price sensitivity

tomers to switch to alternatives. For example, tap water

might be considered a substitute for Coke, whereas Pepsi

• Differential advantage (uniqueness) of industry prodis a competitor’s similar product. Increased marketing for

ucts

drinking tap water might “shrink the pie” for both Coke

• RFM (customer value) Analysis

and Pepsi, whereas increased Pepsi advertising would likely

“grow the pie” (increase consumption of all soft drinks), al• The total amount of trading

beit while giving Pepsi a larger slice at Coke’s expense. Another example is the substitute of traditional phone with a

smart phone.

2.1.4 Bargaining power of suppliers

Potential factors:

The bargaining power of suppliers is also described as the

market of inputs. Suppliers of raw materials, components,

• Buyer propensity to substitute

labor, and services (such as expertise) to the firm can be

• Relative price performance of substitute

a source of power over the firm when there are few substitutes. If you are making biscuits and there is only one

• Buyer switching costs

person who sells flour, you have no alternative but to buy it

• Perceived level of product differentiation

from them. Suppliers may refuse to work with the firm or

• Number of substitute products available in the market charge excessively high prices for unique resources.

• Ease of substitution

• Substandard product

Potential factors are:

• Quality depreciation

• Supplier switching costs relative to firm switching

costs

• Availability of close substitute

• Degree of differentiation of inputs

2.3. CRITICISMS

• Impact of inputs on cost or differentiation

• Presence of substitute inputs

• Strength of distribution channel

• Supplier concentration to firm concentration ratio

• Employee solidarity (e.g. labor unions)

• Supplier competition: the ability to forward vertically

integrate and cut out the buyer.

2.1.5

Intensity of competitive rivalry

For most industries the intensity of competitive rivalry is the

major determinant of the competitiveness of the industry.

7

2.3

Criticisms

Porter’s framework has been challenged by other academics

and strategists such as Stewart Neill. Similarly, the likes of

ABC, Kevin P. Coyne and Somu Subramaniam have stated

that three dubious assumptions underlie the five forces:

• That buyers, competitors, and suppliers are unrelated

and do not interact and collude.

• That the source of value is structural advantage (creating barriers to entry).

• That uncertainty is low, allowing participants in a market to plan for and respond to competitive behavior.[4]

An important extension to Porter was found in the work of

Adam Brandenburger and Barry Nalebuff of Yale School

of Management in the mid-1990s. Using game theory, they

• Sustainable competitive advantage through innovation

added the concept of complementors (also called “the 6th

force”),

helping to explain the reasoning behind strategic

• Competition between online and offline companies

alliances. Complementors are known as the impact of re• Level of advertising expense

lated products and services already in the market. [5] The

idea that complementors are the sixth force has often been

• Powerful competitive strategy

credited to Andrew Grove, former CEO of Intel Corpora• Firm concentration ratio

tion. According to most references, the sixth force is government or the public. Martyn Richard Jones, whilst con• Degree of transparency

sulting at Groupe Bull, developed an augmented 5 forces

model in Scotland in 1993. It is based on Porter’s model

and includes Government (national and regional) as well

2.2 Usage

as Pressure Groups as the notional 6th force. This model

was the result of work carried out as part of Groupe Bull's

Strategy consultants occasionally use Porter’s five forces Knowledge Asset Management Organisation initiative.

framework when making a qualitative evaluation of a firm's Porter indirectly rebutted the assertions of other forces,

strategic position. However, for most consultants, the by referring to innovation, government, and complemenframework is only a starting point or “checklist.” They tary products and services as “factors” that affect the five

might use value chain or another type of analysis in forces.[6]

conjunction.[3] Like all general frameworks, an analysis that

uses it to the exclusion of specifics about a particular situa- It is also perhaps not feasible to evaluate the attractiveness

of an industry independent of the resources a firm brings to

tion is considered naive.

that industry. It is thus argued (Wernerfelt 1984)[7] that this

According to Porter, the five forces model should be used theory be coupled with the Resource-Based View (RBV) in

at the line-of-business industry level; it is not designed to order for the firm to develop a much more sound strategy.

be used at the industry group or industry sector level. An It provides a simple perspective for accessing and analyzindustry is defined at a lower, more basic level: a market ing the competitive strength and position of a corporation,

in which similar or closely related products and/or services business or organization.

are sold to buyers. (See industry information.) A firm that

competes in a single industry should develop, at a minimum,

one five forces analysis for its industry. Porter makes clear

2.4 See also

that for diversified companies, the first fundamental issue

in corporate strategy is the selection of industries (lines of

• Coopetition

business) in which the company should compete; and each

line of business should develop its own, industry-specific,

• National Diamond

five forces analysis. The average Global 1,000 company

• Value chain

competes in approximately 52 industries (lines of business).

Potential factors:

8

CHAPTER 2. PORTER FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS

• Porter’s four corners model

• Industry classification

• Nonmarket forces

• Economics of Strategy

2.5 References

[1] Michael Porter, Nicholas Argyres, Anita M. McGahan, “An

Interview with Michael Porter”, The Academy of Management Executive 16:2:44 at JSTOR

[2] Michael Simkovic, Competition and Crisis in Mortgage Securitization

[3] Tang, David (21 October 2014). “Introduction to Strategy

Development and Strategy Execution”. Flevy. Retrieved 2

November 2014.

[4] Kevin P. Coyne and Somu Subramaniam, “Bringing discipline to strategy”, The McKinsey Quarterly, 1996, Number

4, pp. 14-25

[5] http://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/six-forces-model.

asp

[6] Michael E. Porter. “The Five Competitive Forces that Shape

Strategy”, Harvard Business Review, January 2008, p.86104. PDF

[7] Wernerfelt, B. (1984), A resource-based view of the firm,

Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 5, (April–June): pp.

171-180

2.6 Further reading

• Coyne, K.P. and Sujit Balakrishnan (1996),Bringing

discipline to strategy, The McKinsey Quarterly, No.4.

• Porter, M.E. (March–April 1979) How Competitive

Forces Shape Strategy, Harvard Business Review.

• Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy, Free Press,

New York, 1980.

• Porter, M.E. (2008) The Five Competitive Forces That

Shape Strategy, Harvard business Review, January

2008.

• Ireland, Hoskisson, Understanding Business Strategy.

SOUTH WESTERN.

• Rainer and Turban, Introduction to Information Systems (2nd edition), Wiley, 2009, pp 36–41.

• Kotler Philip, Marketing Management, Prentice-Hall,

Inc. 1997

• Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel,Strategy Safari

1998.

Chapter 3

Porter’s generic strategies

Porter’s generic strategies describe how a company pursues competitive advantage across its chosen market scope.

There are three/four generic strategies, either lower cost,

differentiated, or focus. A company chooses to pursue one

of two types of competitive advantage, either via lower costs

than its competition or by differentiating itself along dimensions valued by customers to command a higher price.

A company also chooses one of two types of scope, either focus (offering its products to selected segments of the

market) or industry-wide, offering its product across many

market segments. The generic strategy reflects the choices

made regarding both the type of competitive advantage and

the scope. The concept was described by Michael Porter in

1980.[1]

gies, product differentiation strategies, and market focus

strategies.[1]

Porter described an industry as having multiple segments

that can be targeted by a firm. The breadth of its targeting refers to the competitive scope of the business. Porter

defined two types of competitive advantage: lower cost

or differentiation relative to its rivals. Achieving competitive advantage results from a firm’s ability to cope

with the five forces better than its rivals. Porter wrote:

"[A]chieving competitive advantage requires a firm to make

a choice...about the type of competitive advantage it seeks

to attain and the scope within which it will attain it.” He

also wrote: “The two basic types of competitive advantage

[differentiation and lower cost] combined with the scope

of activities for which a firm seeks to achieve them lead to

three generic strategies for achieving above average performance in an industry: cost leadership, differentiation and

focus. The focus strategy has two variants, cost focus and

differentiation focus.”[2] In general:

3.1 Concept

S TR ATE GIC TA R GE T

STRATEGIC ADVANTAGE

Industrywide

Uniqueness Perceived

by the Customer

Low Cost Position

DIFFERENTIATION

OVERALL

COST LEADERSHIP

• If a firm is targeting customers in most or all segments

of an industry based on offering the lowest price, it is

following a cost leadership strategy;

• If it targets customers in most or all segments based

on attributes other than price (e.g., via higher product quality or service) to command a higher price, it

is pursuing a differentiation strategy. It is attempting

to differentiate itself along these dimensions favorably

relative to its competition. It seeks to minimize costs

in areas that do not differentiate it, to remain cost competitive; or

STUCK IN THE MIDDLE

Particular

Segment Only

FOCUS

Michael Porter’s Three Generic Strategies

• If it is focusing on one or a few segments, it is following

Porter wrote in 1980 that strategy target either cost leada focus strategy. A firm may be attempting to offer a

ership, differentiation, or focus.[1] These are known as

lower cost in that scope (cost focus) or differentiate

Porter’s three generic strategies and can be applied to any

itself in that scope (differentiation focus).[2]

size or form of business. Porter claimed that a company

must only choose one of the three or risk that the business

would waste precious resources. Porter’s generic strate- The concept of choice was a different perspective on stratgies detail the interaction between cost minimization strate- egy, as the 1970s paradigm was the pursuit of market share

9

10

(size and scale) influenced by the experience curve. Companies that pursued the highest market share position to

achieve cost advantages fit under Porter’s cost leadership

generic strategy, but the concept of choice regarding differentiation and focus represented a new perspective.[3]

3.2 Origins

Empirical research on the profit impact of marketing strategy indicated that firms with a high market share were often

quite profitable, but so were many firms with low market

share. The least profitable firms were those with moderate

market share. This was sometimes referred to as the hole

in the middle problem. Porter’s explanation of this is that

firms with high market share were successful because they

pursued a cost leadership strategy and firms with low market

share were successful because they used market segmentation to focus on a small but profitable market niche. Firms

in the middle were less profitable because they did not have

a viable generic strategy.

Porter suggested combining multiple strategies is successful

in only one case. Combining a market segmentation strategy with a product differentiation strategy was seen as an

effective way of matching a firm’s product strategy (supply

side) to the characteristics of your target market segments

(demand side). But combinations like cost leadership with

product differentiation were seen as hard (but not impossible) to implement due to the potential for conflict between

cost minimization and the additional cost of value-added

differentiation.

CHAPTER 3. PORTER’S GENERIC STRATEGIES

high return on investment, the firm must be able to operate

at a lower cost than its rivals. There are three main ways to

achieve this.

The first approach is achieving a high asset utilization. In

service industries, this may mean for example a restaurant

that turns tables around very quickly, or an airline that turns

around flights very fast. In manufacturing, it will involve

production of high volumes of output. These approaches

mean fixed costs are spread over a larger number of units

of the product or service, resulting in a lower unit cost, i.e.

the firm hopes to take advantage of economies of scale and

experience curve effects. For industrial firms, mass production becomes both a strategy and an end in itself. Higher

levels of output both require and result in high market share,

and create an entry barrier to potential competitors, who

may be unable to achieve the scale necessary to match the

firms low costs and prices.

The second dimension is achieving low direct and indirect

operating costs. This is achieved by offering high volumes

of standardized products, offering basic no-frills products

and limiting customization and personalization of service.

Production costs are kept low by using fewer components,

using standard components, and limiting the number of

models produced to ensure larger production runs. Overheads are kept low by paying low wages, locating premises

in low rent areas, establishing a cost-conscious culture, etc.

Maintaining this strategy requires a continuous search for

cost reductions in all aspects of the business. This will include outsourcing, controlling production costs, increasing

asset capacity utilization, and minimizing other costs including distribution, R&D and advertising. The associated

distribution strategy is to obtain the most extensive distribution possible. Promotional strategy often involves trying

to make a virtue out of low cost product features.

Since that time, empirical research has indicated companies pursuing both differentiation and low-cost strategies

may be more successful than companies pursuing only one

The third dimension is control over the value chain encomstrategy.[4]

passing all functional groups (finance, supply/procurement,

Some commentators have made a distinction between cost

marketing, inventory, information technology etc..) to enleadership, that is, low cost strategies, and best cost stratesure low costs.[5] For supply/procurement chain this could

gies. They claim that a low cost strategy is rarely able to

be achieved by bulk buying to enjoy quantity discounts,

provide a sustainable competitive advantage. In most cases

squeezing suppliers on price, instituting competitive bidfirms end up in price wars. Instead, they claim a best cost

ding for contracts, working with vendors to keep invenstrategy is preferred. This involves providing the best value

tories low using methods such as Just-in-Time purchasing

for a relatively low price.

or Vendor-Managed Inventory. Wal-Mart is famous for

squeezing its suppliers to ensure low prices for its goods.

Other procurement advantages could come from preferen3.3 Cost Leadership Strategy

tial access to raw materials, or backward integration. Keep

in mind that if you are in control of all functional groups

This strategy involves the firm winning market share by ap- this is suitable for cost leadership; if you are only in control

pealing to cost-conscious or price-sensitive customers. This of one functional group this is differentiation. For example

is achieved by having the lowest prices in the target market Dell Computer initially achieved market share by keeping

segment, or at least the lowest price to value ratio (price inventories low and only building computers to order via

compared to what customers receive). To succeed at offer- applying Differentiation strategies in supply/procurement

ing the lowest price while still achieving profitability and a chain. This will be clarified in other sections.

3.5. FOCUS STRATEGIES

Cost leadership strategies are only viable for large firms with

the opportunity to enjoy economies of scale and large production volumes and big market share. Small businesses

can be cost focus not cost leaders if they enjoy any advantages conducive to low costs. For example, a local restaurant in a low rent location can attract price-sensitive customers if it offers a limited menu, rapid table turnover and

employs staff on minimum wage. Innovation of products

or processes may also enable a startup or small company to

offer a cheaper product or service where incumbents’ costs

and prices have become too high. An example is the success of low-cost budget airlines who despite having fewer

planes than the major airlines, were able to achieve market

share growth by offering cheap, no-frills services at prices

much cheaper than those of the larger incumbents. At the

beginning for low-cost budget airlines choose acting in cost

focus strategies but later when the market grow, big airlines

started to offer same low-cost attributes, cost focus became

cost leadership! [5]

11

the product or service but is ineffective when its uniqueness

is easily replicated by its competitors.[6] Successful brand

management also results in perceived uniqueness even when

the physical product is the same as competitors. This way,

Chiquita was able to brand bananas, Starbucks could brand

coffee, and Nike could brand sneakers. Fashion brands rely

heavily on this form of image differentiation.

Differentiation strategy is not suitable for small companies.

It is more appropriate for big companies. To apply differentiation with attributes throughout predominant intensity

in any one or several of the functional groups (finance, purchase, marketing, inventory etc..).[5] This point is critical.

For example GE uses finance function to make a difference. You may do so in isolation of other strategies or

in conjunction with focus strategies (requires more initial

investment).[5] It provides great advantage to use differentiation strategy (for big companies) in conjunction with focus

cost strategies or focus differentiation strategies. Case for

Coca Cola and Royal Crown beverages is good sample for

A cost leadership strategy may have the disadvantage of this.

lower customer loyalty, as price-sensitive customers will

switch once a lower-priced substitute is available. A reputation as a cost leader may also result in a reputation for 3.4.1 Variants on the Differentiation Stratlow quality, which may make it difficult for a firm to rebrand

egy

itself or its products if it chooses to shift to a differentiation

strategy in future.

The shareholder value model holds that the timing of

the use of specialized knowledge can create a differentiation advantage as long as the knowledge remains unique.[7]

3.4 Differentiation Strategy

This model suggests that customers buy products or services

from an organisation to have access to its unique knowlDifferentiate the products/services in some way in order to edge. The advantage is static, rather than dynamic, because

compete successfully. Examples of the successful use of the purchase is a one-time event.

a differentiation strategy are Hero, Honda, Asian Paints, The unlimited resources model utilizes a large base of reHUL, Nike athletic shoes (image and brand mark), BMW sources that allows an organisation to outlast competitors by

Group Automobiles, Perstorp BioProducts, Apple Com- practicing a differentiation strategy. An organisation with

puter (product’s design), Mercedes-Benz automobiles, and greater resources can manage risk and sustain profits more

Renault-Nissan Alliance.

easily than one with fewer resources. This provides a shortA differentiation strategy is appropriate where the target term advantage only. If a firm lacks the capacity for concustomer segment is not price-sensitive, the market is com- tinual innovation, it will not sustain its competitive position

petitive or saturated, customers have very specific needs over time.

which are possibly under-served, and the firm has unique

resources and capabilities which enable it to satisfy these

needs in ways that are difficult to copy. These could include

patents or other Intellectual Property (IP), unique technical

expertise (e.g. Apple’s design skills or Pixar’s animation

prowess), talented personnel (e.g. a sports team’s star players or a brokerage firm’s star traders), or innovative processes. Successful differentiation is displayed when a company accomplishes either a premium price for the product

or service, increased revenue per unit, or the consumers’

loyalty to purchase the company’s product or service (brand

loyalty). Differentiation drives profitability when the added

price of the product outweighs the added expense to acquire

3.5

Focus strategies

This dimension is not a separate strategy for big companies

due to small market conditions. Big companies which chose

applying differentiation strategies may also choose to apply

in conjunction with focus strategies (either cost or differentiation). On the other hand, this is definitely appropriate

strategies for small companies especially for those wanting

to avoid competition with big ones.

In adopting a narrow focus, the company ideally focuses on

12

CHAPTER 3. PORTER’S GENERIC STRATEGIES

a few target markets (also called a segmentation strategy or

niche strategy). These should be distinct groups with specialised needs. The choice of offering low prices or differentiated products/services should depend on the needs of

the selected segment and the resources and capabilities of

the firm. It is hoped that by focusing your marketing efforts

on one or two narrow market segments and tailoring your

marketing mix to these specialized markets, you can better meet the needs of that target market. The firm typically

looks to gain a competitive advantage through product innovation and/or brand marketing rather than efficiency. A

focused strategy should target market segments that are less

vulnerable to substitutes or where a competition is weakest

to earn above-average return on investment.

which clearly contradicts with the basis of low cost strategy

and on the other hand relatively standardised products with

features acceptable to many customers will not carry any

differentiation[9] hence, cost leadership and differentiation

strategy will be mutually exclusive.[8] Two focal objectives

of low cost leadership and differentiation clash with each

other resulting in no proper direction for a firm. In particular, Miller[10] questions the notion of being “caught in the

middle”. He claims that there is a viable middle ground between strategies. Many companies, for example, have entered a market as a niche player and gradually expanded.

According to Baden-Fuller and Stopford (1992) the most

successful companies are the ones that can resolve what they

call “the dilemma of opposites”. Furthermore, Reeves and

Routledge’s (2013) study of entrepreneurial spirit demonExamples of firm using a focus strategy include Southwest

Airlines, which provides short-haul point-to-point flights in strated this is a key factor in organisation success, differencontrast to the hub-and-spoke model of mainstream carri- tiation and cost leadership were the least important factors.

ers, United, and American Airlines.

However, contrarily to the rationalisation of Porter, contemporary research has shown evidence of successful firms

practising such a “hybrid strategy”.[11] Research writings

of Davis (1984 cited by Prajogo 2007, p. 74) state that

3.6 Recent developments

firms employing the hybrid business strategy (Low cost and

differentiation strategy) outperform the ones adopting one

Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema (1993) in their book

generic strategy. Sharing the same view point, Hill (1988

The Discipline of Market Leaders have modified Porter’s

cited by Akan et al. 2006, p. 49) challenged Porter’s conthree strategies to describe three basic “value disciplines”

cept regarding mutual exclusivity of low cost and differenthat can create customer value and provide a competitive

tiation strategy and further argued that successful combinaadvantage. They are operational excellence, product leadtion of those two strategies will result in sustainable comership, and customer intimacy.

petitive advantage. As to Wright and other (1990 cited by

A popular post-Porter model was presented by W. Chan Akan et al. 2006, p. 50) multiple business strategies are reKim and Renée Mauborgne in their 1999 Harvard Business quired to respond effectively to any environment condition.

Review article “Creating New Market Space”. In this ar- In the mid to late 1980s where the environments were relaticle they described a “value innovation” model in which tively stable there was no requirement for flexibility in busicompanies must look outside their present paradigms to find ness strategies but survival in the rapidly changing, highly

new value propositions. Their approach complements most unpredictable present market contexts will require flexibilof Porter’s thinking, especially the concept of differentia- ity to face any contingency (Anderson 1997, Goldman et

tion. They later went on to publish their ideas in the book al. 1995, Pine 1993 cited by Radas 2005, p. 197). After

Blue Ocean Strategy. Thus it is difficult, but not impossible, eleven years Porter revised his thinking and accepted the

to topple a firm that has established a dominant standard.

fact that hybrid business strategy could exist (Porter cited

by Prajogo 2007, p. 70) and writes in the following manner.

3.7 Criticisms of generic strategies

Several commentators have questioned the use of generic

strategies claiming they lack specificity, lack flexibility, and

are limiting.

Porter stressed the idea that only one strategy should be

adopted by a firm and failure to do so will result in “stuck

in the middle” scenario.[8] He discussed the idea that practising more than one strategy will lose the entire focus of

the organization hence clear direction of the future trajectory could not be established. The argument is based on the

fundamental that differentiation will incur costs to the firm

Though Porter had a fundamental rationalisation in his concept about the invalidity of hybrid business strategy, the

highly volatile and turbulent market conditions will not permit survival of rigid business strategies since long-term establishment will depend on the agility and the quick responsiveness towards market and environmental conditions.

Market and environmental turbulence will make drastic implications on the root establishment of a firm. If a firm’s

business strategy could not cope with the environmental and

market contingencies, long-term survival becomes unrealistic. Diverging the strategy into different avenues with

the view to exploit opportunities and avoid threats cre-

3.9. REFERENCES

13

ated by market conditions will be a pragmatic approach for [11] Hambrick, D, “An empirical typology of mature industrial

product environments” Academy of Management Journal,

a firm.[10][12][13] Critical analysis done separately for cost

26: 213-230. (1983)

leadership strategy and differentiation strategy identifies elementary value in both strategies in creating and sustain- [12] Murray, A.I. “A contingency view of Porter’s “generic strateing a competitive advantage. Consistent and superior pergies.” Academy of Management Review, 13: 390-400.

formance than competition could be reached with stronger

(1988)

foundations in the event “hybrid strategy” is adopted. Depending on the market and competitive conditions hybrid [13] Wright, P, “A refinement of Porter’s strategies.” Strategic

Management Journal, 8: 93-101.(1987)

strategy should be adjusted regarding the extent which each

generic strategy (cost leadership or differentiation) should

be given priority in practice.

3.8 See also

• Critique of generic strategies and their limitations, including Porter - “Generic strategies: a substitute for

thinking?"

Orcullo, Jr., N. A., Fundamentals of Strategic Management

3.9 References

[1] Porter, Michael E. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press.

ISBN 0-684-84148-7.

[2] Porter, Michael E. (1985). Competitive Advantage. Free

Press. ISBN 0-684-84146-0.

[3] Kiechel, Walter (2010). The Lords of Strategy. Harvard

Business Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-782-3.

[4] Wright, Peter, Kroll, Mark, Kedia, Ben, and Pringle,

Charles. 1990. Strategic Profiles, Market Share, and Business Performance. Industrial Management, May 1, pp23-28.

[5] Wright, P, “A refinement of Porter’s strategies.”

[6] Gamble, Arthur A. Thompson, Jr., A.J. Strickland III, John

E. (2010). Crafting and executing strategy : the quest for competitive advantage : concepts and cases (17th ed.). Boston:

McGraw-Hill/Irwin. p. 149. ISBN 9780073530420.

[7] William E. Fruhan, Jr., “The NPV Model of Strategy—The

Shareholder Value Model,” in Financial Strategy: Studies

in the Creation, Transfer, and Destruction of Shareholder

Value (Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, 1979)

[8] Porter, M.E., “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors” New York: The Free Press

(1980)

[9] Panayides, “Unknown” (2003)

[10] Miller, D., “The generic strategy trap” in The Journal of

Business Strategy 13(1):37-41 1992)

Chapter 4

Competitive advantage

Competitive advantage is a business concept describing attributes that allow an organization to outperform its

competitors. These attributes may include access to natural

resources, such as high grade ores or inexpensive power,

highly skilled personnel, geographic location, high entry

barriers, etc. New technologies, such as robotics and information technology, can also provide competitive advantage,

whether as a part of the product itself, as an advantage to

the making of the product, or as a competitive aid in the

business process (for example, better identification and understanding of customers).

and Lynch 1999, p. 45).[3] The study of such advantage

has attracted profound research interest due to contemporary issues regarding superior performance levels of firms in

the present competitive market conditions. “A firm is said

to have a competitive advantage when it is implementing

a value creating strategy not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential player” (Barney 1991

cited by Clulow et al.2003, p. 221).[4]

The term competitive advantage refers to the ability gained

through attributes and resources to perform at a higher level

than others in the same industry or market (Christensen and

Fahey 1984, Kay 1994, Porter 1980 cited by Chacarbaghi

The goal of cost leadership strategy is to offer products or

services at the lowest cost in the industry. The challenge

of this strategy is to earn a suitable profit for the company,

rather than operating at loss and draining profitability from

Successfully implemented strategies will lift a firm to superior performance by facilitating the firm with competitive

advantage to outperform current or potential players (Passemard and Calantone 2000, p. 18).[5] To gain competitive

advantage, a business strategy of a firm manipulates the various resources over which it has direct control and these re4.1 Overview

sources have the ability to generate competitive advantage

(Reed and Fillippi 1990 cited by Rijamampianina 2003, p.

Michael Porter defined the two types of competitive ad- 362).[6] Superior performance outcomes and superiority in

vantage an organization can achieve relative to its rivals: production resources reflects competitive advantage (Day

lower cost or differentiation. This advantage derives from and Wesley 1988 cited by Lau 2002, p. 125).[7]

attribute(s) that allow an organization to outperform its

competition, such as superior market position, skills, or Above writings signify competitive advantage as the ability

resources. In Porter’s view, strategic management should to stay ahead of present or potential competition. Also, it

be concerned with building and sustaining competitive provides the understanding that resources held by a firm and

the business strategy will have a profound impact on genadvantage.[1]

erating competitive advantage. Powell (2001, p. 132)[8]

Competitive advantage seeks to address some of the criti- views business strategy as the tool that manipulates the recisms of comparative advantage. Porter proposed the the- sources and create competitive advantage, hence, viable

ory in 1985. Porter emphasizes productivity growth as the business strategy may not be adequate unless it possess confocus of national strategies. Competitive advantage rests trol over unique resources that has the ability to create such

on the notion that cheap labor is ubiquitous and natural re- a unique advantage.

sources are not necessary for a good economy. The other

theory, comparative advantage, can lead countries to specialize in exporting primary goods and raw materials that

trap countries in low-wage economies due to terms of trade. 4.2 Generic competitive strategies

Competitive advantage attempts to correct for this issue by

stressing maximizing scale economies in goods and services 4.2.1 Cost leadership strategy

that garner premium prices (Stutz and Warf 2009).[2]

14

4.3. SEE ALSO

all market players. Companies such as Walmart succeed

with this strategy by featuring low prices on key items on

which customers are price-aware, while selling other merchandise at less aggressive discounts. Products are to be

created at the lowest cost in the industry. An example is

to use space in stores for sales and not for storing excess

product.

15

4.3

See also

• Resource-based view

• Core competency

• Economies of scale

• Comparative advantage

• Value chain

4.2.2

Differentiation strategy

The goal of differentiation strategy is to provide a variety of

products, services, or features to consumers that competitors are not yet offering or are unable to offer. This strategy

gives a direct advantage to the company which is able to provide a unique product or service that none of its competitors

are able to offer. An example is Dell which launched masscustomizations on computers to fit consumers’ needs. This

allows the company to make its first product to be the star

of its sales.

4.2.3

Innovation strategy

Porter describes innovation strategy as determining how,

and to what degree, firms use innovation to deliver a unique

mix of value and achieve competitive advantage.[9] The goal

of innovation strategy is to leapfrog other market players by

the introduction of completely new or notably better products or services. This strategy is typical for technology startup companies which often intend to “disrupt” the existing

marketplace, obsoleting the current market entries with a

breakthrough product offering. It is harder for more established companies to pursue this strategy because their

product offering has achieved market acceptance. Apple

has been a notable example of using this strategy with its introduction of iPod personal music players, and iPad tablets.

Many companies invest heavily in their research and development programs to achieve such statuses with their innovations.

4.2.4

Operational effectiveness strategy

The goal of operational effectiveness as a strategy is to perform internal business activities better than competitors,

making the company easier or more pleasurable to do business with than other market choices. It improves the characteristics of the company while lowering the time it takes

to get the products on the market with a great start.

• Differentiation (economics)

• Cost leadership

• Tacit knowledge

4.4

References

[1] Porter, Michael E. (1985). Competitive Advantage. Free

Press. ISBN 0-684-84146-0.

[2] Warf, Frederick P. Stutz, Barney (2007). The World Economy: Resources, Location, Trade and Development (5th ed.).

Upper Saddle River: Pearson. ISBN 0132436892.

[3] Chacarbaghi; Lynch (1999), Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance by Michael E.

Porter 1980, p. 45

[4] Clulow, Val; Gerstman, Julie; Barry, Carol (1 January

2003). “The resource-based view and sustainable competitive advantage: the case of a financial services firm”.

Journal of European Industrial Training 27 (5): 220–232.

doi:10.1108/03090590310469605.

[5] Passemard; Calantone (2000), Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance by Michael E.

Porter 1980, p. 18

[6] Rijamampianina, Rasoava; Abratt, Russell; February, Yumiko (2003). “A framework for concentric diversification

through sustainable competitive advantage”. Management

Decision 41 (4): 362. doi:10.1108/00251740310468031.

[7] Lau, Ronald S (1 January 2002). “Competitive factors and their relative importance in the US electronics and computer industries”. International Journal of

Operations & Production Management 22 (1): 125–135.

doi:10.1108/01443570210412105.

[8] Powell, Thomas C. (1 September 2001). “Competitive

advantage: logical and philosophical considerations”.

Strategic Management Journal 22 (9):

875–888.

doi:10.1002/smj.173.

[9] Saemundsson, R. J. and Candi, M. (2014), Antecedents

of Innovation Strategies in New Technology-based Firms:

Interactions between the Environment and Founder Team

Composition. Journal of Product Innovation Management,

31: 939–955. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12133

16

4.5 Further reading

• Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance by Michael E. Porter

• Creating Competitive Advantage: Give Customers a

Reason to Choose You Over Your Competitors by Jaynie

L. Smith

• Using MIS by David M. Kroenke pages 71–77

• Unraveling The Resource-Based Tangle by Peteraf M.

& Barney J (2003). Managerial and Decision Economics 24. doi:10.1002/mde.1126

• Erica Olsen (2012). Strategic Planning Kit for Dummies, 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

• Profit from the Core: Growth Strategy in an Era of Turbulence by Chris Zook and James Allen

• Beyond the Core: Expand Your Market Without Abandoning Your Roots by Chris Zook

• Unstoppable: Finding Hidden Assets to Renew the Core

and Fuel Profitable Growth by Chris Zook

• Value Migration: How to Think Several Moves Ahead

of the Competition by Adrian Slywotzky

4.6 External links

• Competitive Advantage

• Porter and Competitive Advantage

• Competitive Advantage in Business

CHAPTER 4. COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

Chapter 5

Value chain

A value chain is a set of activities that a firm operating in a specific industry performs in order to deliver a

valuable product or service for the market. The concept

comes from business management and was first described

and popularized by Michael Porter in his 1985 best-seller,

Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior

Performance.[1]

The idea of the value chain is based on the

process view of organizations, the idea of seeing

a manufacturing (or service) organization as a

system, made up of subsystems each with inputs,

transformation processes and outputs. Inputs,

transformation processes, and outputs involve

the acquisition and consumption of resources money, labour, materials, equipment, buildings,

land, administration and management. How

value chain activities are carried out determines

costs and affects profits.

— IfM, Cambridge[2]

Michael Porter’s Value Chain

5.1

Firm-level

The appropriate level for constructing a value chain is the

business unit,[5] not division or corporate level. Products

pass through a chain of activities in order, and at each activity the product gains some value. The chain of activities

gives the products more added value than the sum of added

values of all activities.[5]

The activity of a diamond cutter can illustrate the difference

between cost and the value chain. The cutting activity may

have a low cost, but the activity adds much of the value to

the end product, since a rough diamond is significantly less

valuable than a cut diamond. Typically, the described value

chain and the documentation of processes, assessment and

auditing of adherence to the process routines are at the core

of the quality certification of the business, e.g. ISO 9001.

The concept of value chains as decision support tools, was

added onto the competitive strategies paradigm developed

by Porter as early as 1979.[3] In Porter’s value chains, Inbound Logistics, Operations, Outbound Logistics, Marketing and Sales, and Service are categorized as primary activities. Secondary activities include Procurement, Human Resource management, Technological Development and In- A firm’s value chain forms a part of a larger stream of acfrastructure (Porter 1985, pp. 11–15).[1][2]

tivities, which Porter calls a value system. A value system,

According to the OECD Secretary-General (Gurría or an industry value chain, includes the suppliers that pro2012)[4] the emergence of global value chains (GVCs) in vide the inputs necessary to the firm along with their value

the late 1990s provided a catalyst for accelerated change in chains. After the firm creates products, these products pass

the landscape of international investment and trade, with through the value chains of distributors (which also have

major, far-reaching consequences on governments as well their own value chains), all the way to the customers. All

as enterprises (Gurría 2012).[4]

parts of these chains are included in the value system. To

17

18

CHAPTER 5. VALUE CHAIN

achieve and sustain a competitive advantage, and to support a firm performs in designing, producing, marketing, delivthat advantage with information technologies, a firm must ering and supporting its product. Each of these activities

understand every component of this value system.

can contribute to a firm’s relative cost position and create a

basis for differentiation.

5.1.1

Primary activities

• Inbound Logistics: arranging the inbound movement

of materials, parts, and/or finished inventory from

suppliers to manufacturing or assembly plants, warehouses, or retail stores

• Operations: concerned with managing the process that

converts inputs (in the forms of raw materials, labor,

and energy) into outputs (in the form of goods and/or

services).

• Outbound Logistics: is the process related to the storage and movement of the final product and the related

information flows from the end of the production line

to the end user

• Marketing and Sales: selling a product or service

and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.

• Service: includes all the activities required to keep the

product/service working effectively for the buyer after

it is sold and delivered.

5.1.2

Support activities

Michael Porter[6]

The value chain categorizes the generic value-adding activities of an organization. The activities considered under this

product/service enhancement process can be broadly categorized under two major activity-sets.

1. Physical/traditional value chain: a physical-world activity performed in order to enhance a product or a

service. Such activities evolved over time by the experience people gained from their business conduct. As

the will to earn higher profit drives any business, professionals (trained/untrained) practice these to achieve

their goal.

2. Virtual value chain: The advent of computer-based

business-aided systems in the modern world has led

to a completely new horizon of market space in modern business-jargon - the cyber-market space. Like

any other field of computer application, here also we

have tried to implement our physical world’s practices to improve this digital world. All activities of

persistent physical world’s physical value-chain enhancement process, which we implement in the cybermarket, are in general terms referred to as a virtual

value chain.

• Procurement: the acquisition of goods, services or In practice as of 2013, no progressive organisation can afworks from an outside external source

ford to remain stuck to any one of these value chains. In or• Human Resources Management: consists of all activi- der to cover both market spaces (physical world and cyber

ties involved in recruiting, hiring, training, developing, world), organisations need to deploy their very best praccompensating and (if necessary) dismissing or laying tices in both of these spaces to churn out the most informative data, which can further be used to improve the

off personnel.

ongoing products/services or to develop some new prod• Technological Development: pertains to the equip- uct/service. Hence organisations today try to employ the

ment, hardware, software, procedures and technical combined value chain.

knowledge brought to bear in the firm’s transformation

Combined Value Chain = Physical Value shown in sample

of inputs into outputs.

below.

• Infrastructure:

consists of activities such as This value-chain matrix suggests that there are a number of

accounting, legal, finance, control, public rela- opportunities for improvement in any business process.

tions, quality assurance and general (strategic)

management.

5.2

5.1.3

Industry-level

Physical, virtual and combined value

An industry value-chain is a physical representation of the

chain

various processes involved in producing goods (and serCompetitive advantage cannot be understood by looking at vices), starting with raw materials and ending with the deliva firm as a whole. It stems from the many discrete activities ered product (also known as the supply chain). It is based on

5.4. SIGNIFICANCE

the notion of value-added at the link (read: stage of production) level. The sum total of link-level value-added yields

total value. The French Physiocrats’ Tableau économique is

one of the earliest examples of a value chain. Wasilly Leontief’s Input-Output tables, published in the 1950s, provide

estimates of the relative importance of each individual link

in industry-level value-chains for the U.S. economy.

5.3 Global value chains (GVCs)

19

commonly associated with export-oriented trade, development practitioners have begun to highlight the importance

of developing national and intra-regional chains in addition

to international ones.[11]

For example, the International Crops Research Institute

for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) has investigated

strengthening the value chain for sweet sorghum as a biofuel

crop in India. Its aim in doing so was to provide a sustainable means of making ethanol that would increase the incomes of the rural poor, without sacrificing food and fodder

security, while protecting the environment.[12]

Main article: Global value chain

5.4

5.3.1

Cross border / cross region value

The value chain framework quickly made its way to the

chains

Often multinational enterprises (MNEs) developed global

value chains, investing abroad and establishing affiliates

that provided critical support to remaining activities at

home. To enhance efficiency and to optimize profits, multinational enterprises locate “research, development, design,

assembly, production of parts, marketing and branding”

activities in different countries around the globe. MNEs

offshore labour-intensive activities to China and Mexico,

for example, where the cost of labor is the lowest.(Gurría