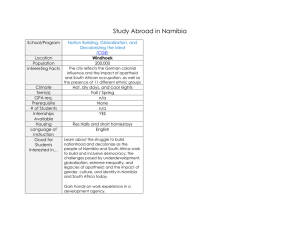

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2011) http://lexikos.journals.ac.za 216 Resensies/Reviews J.K. Kloppers, D. Nakare and L.M. Isala (Compilers), A.W. BredelI (Editor). Bukenkango Rukwangali-English. English-Rukwangali Dictionary, 1st edition 1994, ii + 164pp. ISBN 0-86848-878-X. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan. Price N$48,38. This book is the first publication with English both as the target and source language for the Kwangali language (Rukwangall) spoken in the Okavango Region of Northern Namibia. Although the data given in the 1991 population census for all so-called Kavango peoples do not indicate the exact figure for the Kwangali ethnic group, it is generally accepted that Rukwangali is the dominant medium in the Region either as mother tongue or spoken as a second language. This fact may also be illustrated by the number of those who are taught in Rukwangali in lower primary (Grade 1-3) compared with other Kavango languages which are also media of instruction, i.e. Rugciriku and Thimbukushu. Details extracted from the 1993 Annual Education Census for Namibia are as follows: number of learners mother tongue speakers Rukwangali 16872 11768 Rugdriku 4100 3981 Thimbukushu 2904 2775 Language In addition Rukwangali is a school subject up to Grade 11 at the end of which students sit for the International General Certificate of Secondary Education. Resulting from its actual position in particular in education, there is a growing need for reference materials including those which assist learners in finding the adequate equivalent in the official language which is English (and vice versa). So far, lexicographic work done for Kavango languages is in its infancy. In 1957 a Rukwangali-German word list of approx. 1100 entries was published by Dammann in his "Studien zum Kwangali". The book under review is actually based on a glossary compiled by the late J.K. Kloppers who was employed by the Native Language Bureau of the then Department of Bantu Education before Independence. In those days Kloppers was also the Chairman of the Kwangali Language Committee as well as in charge of other Kavango languages. Thus, the glossary referred to contains also equivalents for Thimbukushu and Rugciriku. The lexical stock which forms the backbone of the present book is in large parts adopted from this glossary and expanded by everyday vocabulary and expressions. Nonetheless, the impact of the original source is felt time and again, for there is an imbalance between medical terms, of which there are Lexikos 5 (AFRILEX-reeks/series 58: 1995): 216-218 Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2011) http://lexikos.journals.ac.za Resensies/Reviews 217 many in the glossary, and entries from other domains. The publication, as indicated in its title, is divided into two sections. In part I (pp. 1-49) the target language is English, in part 11 (pp. 53-156) Rukwangali. This partition makes it clear that the second part is larger than the first one. In fact, there are approx. 3000 English entries against about 1900 for Rukwangali. In other words, the English part is an expanded version of the Rukwangali vocabulary. Four appendices complete the publication, in turn covering names for places, plants, birds and larger mammals. These appendices (excluding place names) summ,arize lexical elements which are already entered in the preceding main parts of the book. They are in fact a mere replica of Kloppers's material, for the appendices are less comprehensive and exclude a number of entries in the actual work. Thus, under "wild" one finds run-ons like "wild asparagus, wild date-palm, wild orange, wild-sage" and separately "wildplum" or "luckybean" which do not turn up in Appendix 2. Although the book is called a dictionary by the compilers, it is rather a vocabulary, the reason being that examples which illustrate the use of equivalents for an entry are scarce. Accordingly, it is mostly left to the user to decide which of the lexical elements given for the target language suits his/her intention. The disproportion between the English and Rukwangali parts is striking. While "milk" is an entry in the English part, its equivalent "masini" does not turn up in the Rukwangali part. The same applies to "magadi" (fat, oil), "mahinatopatopi" (typewriter) or "kapaya" (ribbon) and many others. Some substantial lexical elements, e.g. "mbere" (knife), are missing in both parts. "Mugara" (man) is used in explanations (comp. possessive "his"), but one looks for this noun in vain in the Rukwangali part, while "mukadi" (woman) is there. There is a short introduction on how to use the publication as well as on how various form classes are entered there. For the adjectives the compilers follow the conventional approach of giving the stem preceded by a hyphen. Subsequently, this is explained by means of three examples, but neither of these lexical elements exists in the Rukwangali part of the book. "-Zera"(white) and "-wa" (good, nice) are at least mentioned under this meaning in the English part. "-Mpo" (said to be an adjectival equivalent of "traditional") is found under "tradition" as well as "traditional". Under the former entry "mpo" is followed by a plural marker which clearly points to its status as a noun, while the qualifying function ("traditional") results from its occurrence in a postnominal clause of the structure (N) + connective -~ + N, i.e. "a song of tradition" > "a traditional song". The way the class markers after the noun are indicated differs from most dictionaries for class languages in so far as there is no space left between the entry and its plural marker. No reason whatsoever is given for this format, although one may guess that this goes back to word-processing. Another weak point is the treatment of the reflexive marker which is not identified at all. Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2011) http://lexikos.journals.ac.za 218 Resensies/Reviews Instead, various verbs are entered under "li... " such as "lidaya" (hit oneself), "liguma" (touch each other) or "likanganga" (praise oneself). These entries are more or less redundant since they may be easily derived from non-reflexive, basic verbs like "daya", "guma" and "kanganga" which are all given. In addition, it is not clear why some nouns are entered in a plural fonn, e.g. "mahwa" (waterlily plants) and not "ehwa". Similarly "makopa" and "makwewo" (fruits of indigenous trees) as well as "mandjembere" (grapes), while for the latter under English "grape" one finds at least "endjembere". It is evident that the publication under review lacks lexicographical fundamentals as partly demonstrated above. But for all shortcomings pointed out here one has to acknowledge the fact that a much needed reference source for an important Namibian language is now available. One cannot wait until Namibians more qualified in lexicography get down to compiling a dictionary which is founded on a sound lexicographic basis. Dictionary-making for most Namibian languages has to be done as soon as possible and by all means. Otherwise, the gap between the official language and those which have already functionally become minority languages will become wider. Therefore, all potential compilers are invited to play their part. It is, however, up to the publishers to avoid, as much as possible, bottlenecks. They should do everything to guarantee a qualified adjudication of the manuscript by lexicographers or linguists. Mother tongue competence of the compiler is alone not enough to produce a solid piece of work, as it is not complemented by an adequate theoretical background in the subject matter. In this context - to end with a hopeful infonnation for Rukwangali enthusiasts - a more comprehensive Rukwangali-English dictionary is being prepared by Father M. Forg who has been in the Kavango area for many years. Karsten Legere Department of African Languages University of Namibia Windhoek Namibia