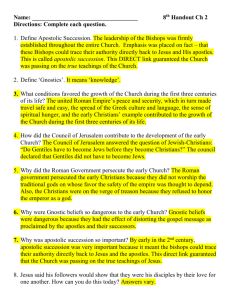

PAURASTYA VIDYĀPĪṬHAM INSTITUTE OF EASTERN CANON LAW HIERARCHICAL AUTHORITY IN THE INDIAN CHURCH A Historico-Juridical Exposition on the Constitution of the Hierarchy of Syro-Malabar Church Joseph Antony Kottayam February 15, 2022 TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................. 1 1. APOSTOLIC PERIOD ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Early Sources of the Apostolic Origin and Hierarchy ...................................................... 2 2. EAST SYRIAN PERIOD .................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Persian Migrations to India ............................................................................................... 3 2.2. Chaldean Patriarchate and Metropolitan-Archdeacon Hierarchy ..................................... 4 3. PAPAL PRIMACY AND INDIAN CHURCH ................................................................ 5 3.1. Doctrine of Papal Primacy in the Apostolic Period .......................................................... 5 3.2. Doctrine of Papal Primacy in the Chaldean Period .......................................................... 6 3.3. John Marignolli OFM (1348/9) ........................................................................................ 6 3.4. Joseph the Indian in Rome in 1502 ................................................................................... 7 3.5. East Syrian Understanding of the Doctrine of Papal Primacy .......................................... 7 4. LATIN PERIOD: PADROADO – PROPAGANDA JURISDICTION ........................ 7 4.1. Padroado Jurisdiction and the Loss of All India Jurisdiction ........................................... 8 4.2. Propaganda Jurisdiction and Erection of Latin Vicariates ................................................ 8 4.3. Erection of Two Separate Vicariates Exclusively for St Thomas Christians ................... 9 5. SYRO-MALABAR PERIOD .......................................................................................... 10 5.1. Erection of Three Vicariates and Native Bishops ........................................................... 10 5.2. Constitution of Syro-Malabar Hierarchy: The Erection of Eparchies and Exarchies ..... 10 5.3. Syro-Malabar Church as Major Archiepiscopal Church ................................................ 12 5.5. The Erection of New Metropolitan Provinces and Eparchies ......................................... 14 CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................... 15 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………16 Introduction Today the Catholic Church in India is composed of Christians belonging to three sui iuris Churches: Syro-Malabar Church, Syro-Malankara Church, and Latin Church. In this seminar paper, we are concerned with the Syro-Malabar Church. Through this scientific work, we wish to make a historico-juridical appraisal of the hierarchical authority in the Indian Church. This study focuses on the constitution of the Syro-Malabar hierarchy. The whole paper is divided into five sections. In the first section, which is entitled ‘Apostolic period’, we study the apostolic origin of the Indian Church. The second section deals with the ‘East Syrian Period’. In this period, we could see a deep-rooted relationship between the sister Churches of Persian Empire and India. In the third section ‘Papal Primacy and the Indian Church’, we study the St Thomas Christians’ understanding of the doctrine of papal primacy. The fourth section introduces the ‘Latin period’ which had begun with the arrival of the Portuguese. During this period St Thomas Christians were under the jurisdiction of Padroado and Propaganda. In the fifth section ‘the Syro-Malabar period’ we notice the erection of vicariates and appointment of native bishops and the gradual development of the Syro-Malabar Hierarchy. In this period, we could see the re-birth of St Thomas Christians under the new tile ‘Syro-Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Church’. 1. Apostolic Period In the very ancient pseudo work ‘the Doctrine of the Apostles’ we read: “India and all its regions and those bordering it as far as the farthest sea, received the hand of the Apostles from Thomas who was the ruler and preceptor in the Church he founded and ministered to there.”1 The Indian Church in the tradition is known as the Church of Thomas Christians. Placid J. Podipara states “By the Church of Thomas Christians, we mean the most ancient Church of India which gravitated towards Malabar, the home and habitat of those who are even today known as ‘Thomas Christians’. In fact, the Church of Malabar was known as the Church of India.”2 According to the tradition, the Apostle Thomas, who confirmed his faith in the Risen Lord by pronouncing him Lord and God (Jn 20: 28), arrived at the ancient port of Muzaris on Ebedjesus (Abdiso) Sobensis, Collectio Canonum Synodicorum, in Mai (ed.) “Scriptorum Veterum Nova Collectio e Vaticanis Codicibus Edita” (Romae, 1838), 7, as cited in Placid J. Podipara, The Hierarchy of the Syro-Malabar Church (Alleppey: Prakasam Publications, 1976) 24 (hereafter cited as Hierarchy). 2 Placid J. Podipara, Four Essays on the Pre-Seventeenth Century Church of the Thomas Christians of India (Malabar) (Changanassery: Sandesanilayam Publications, 1997), 7. 1 the Malabar Coast (Cranganore) in the middle of the first century (AD 52). In Cranganore, Palayur, Kottakkavu near Parur, Kokkamangalam in south Pallippuram, Niranam in Thiruvalla, Quilon, and Chayal near Nilackal, he converted many to Christian faith and formed seven Christian communities. He appointed deacons, presbyters, and bishops to continue the ministry. After that, Apostle Thomas died as a martyr at Mylapore near Madras, where his tomb is venerated even today.3 1.1. Early Sources of the Apostolic Origin and Hierarchy Acts of Thomas (ca AD 200) is one of the important sources to study the history of the evangelization of India by the Apostle Thomas. Acts of Thomas offers information regarding the Apostle’s voyage to India, his mission works, miracles, martyrdom, and burial in India. Apart from this written Apocryphal work, the other sources of the Apostolic origin of the Indian Church are the oral traditions that were handed from generation to generation by the word of the mouth. Some details of these oral traditions can be found in the folk songs such as Ramban Pattu or Thomaparvam (song of Thomas), Veeradyan Pattu (recited by a particular Hindu caste), and Margam Kali Pattu (the song-play of the way). The existence of the Christian community in South India (Malabar) from the very first century, who were called ‘Thomas Christians’ is the most important source that proves the Apostolic origin of the Indian Church.4 In the canonical collection of the West Syrian Tradition ‘Synodicon’, the hierarchical succession of the Indian Church from the Apostle is portrayed as: “India and all the countries in the periphery up to the farthest sea received the ordination to the priesthood from Apostle Thomas who was their leader and superintendent in the Church which he had built there and which he served.”5 We find the names Kepa and Paul in the Song of the Rabban Thomas (Ramban Pattu), who were ordained bishops directly by the Apostle for the territories of Malabar and Coromandal on India's south-east coast. This line of episcopacy, according to tradition, continued for a few centuries. 2. East Syrian Period St Thomas Christians in India were depending on the patriarch of the Church of the East in the Persian Empire from the fourth century onwards for the appointment and 3 Paul Pallath, The Catholic Church in India (Rome: Mar Thoma Yogam, 2005), 3. Paul Pallath, The Catholic Church in India, 4-6. 5 Vööbus, "The Teaching of Addai", 195. as cited in Joy George Mangalathil, “The Metropolitan and Gate of All India: A Proud Legacy of the St Thomas Christians,” in The All-India Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church, Qanona 6 (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2019), 76. 4 2 consecration of bishops due to various historical, ecclesiastical, and canonical reasons. 6 Around the fourth century in the Churches of Roman and Persian empires, the hierarchical structure began to develop. During that period the Indian Church was not large enough to establish itself into such a hierarchy. According to the tradition, Persecution and internal conflicts weakened the Church in Malabar during the time. The canons of the First Council of Nicaea had far-reaching impacts on the hierarchical development of the Church of India. The Council had appointed thirteen council fathers to carry its symbol of faith and the twenty constitutions to the churches in various territories. Mar John of Persia, representing the Churches of Persia and India, was one of them. As per canon 4 of Nicaea I “A bishop is to be chosen by all the bishops of the province, or at least by three, the rest giving by letter their assent; but this choice must be confirmed by the Metropolitan.” 7 St Thomas Christians of India had been reduced to a small community when the Council constitutions were conveyed to them. Hence, they were not able to form a full-fledged hierarchy with a great Metropolitan and Bishops. As a result, for the episcopal succession, the Indian Church had no choice but to rely on a Church with a full hierarchical structure, as mandated by the Nicaea I. So, the Indian Church relied on the Persian Church with which they had a common apostolic origin and was accessible to them through trade routes. At the request of the Thomas Christians of India, the Patriarch of the East began sending bishops from the fourth century.8 2.1. Persian Migrations to India The arrival of some migrant Christians from Persia re-energized the ancient Christian community in Malabar. However, we are not sure why, how, or when these migrations took place. Mainly there are two views concerning this. Some historians are of the view that they came as refugees fleeing from the severe religious persecution of the Sassanid emperors. Though many other migrations are known, two are more well-known in tradition: one related with Thomas of Cana (around the fourth century) and the other with two saintly men named Sapor and Prot in the ninth or eleventh centuries. 9 6 Paul Pallath, The Catholic Church in India, 10. Philip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol 14, The Seven Ecumenical Councils (Grand Rapids, Michigan: WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994), 58, accessed February 09, 2022, https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.html. 8 Joseph Perumthottam, “Historical Evolution of the Hierarchy of the Syro-Malabar Church,” in Mar Thoma Margam: The Ecclesial Heritage of the St Thomas Christians, ed. Andrews Mekkattukunnel (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2012), 782-783 (hereafter cited as Mar Thoma Margam). 9 Joy George Mangalathil, “The Metropolitan and Gate of All India: A Proud Legacy of the St Thomas Christians”, in The All-India Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church, Qanona 6 (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2019), 78 (hereafter cited as All-India Jurisdiction). 7 3 Another view concerning these migrations is that they were sent by the East Syrian Patriarch at the request of the Indian Church. According to the tradition around the fourth century Bishop Uraha Mar Yausef, four priests, several deacons and about 400 Christians led by Thomas of Cana migrated to Cranganore with the blessing of the Patriarch.10 2.2. Chaldean Patriarchate and Metropolitan-Archdeacon Hierarchy From the beginning of its hierarchical relationship with the Persian Church, the Indian Church was indirectly related to the Chaldean. When the local Churches in the Persian Empire recognized the Seleucian Church's supremacy, the Church in India accepted it as well, and so directly came under Chaldean jurisdiction.11 The Chaldean Patriarch Isoyahb (c.650-660) or his successor Sliba Zcha (714-728) elevated the Indian Church to the metropolitan status. It was Patriarch Timothy I (780/89823) who took Indian Church away from under the Persian Church and placed it directly under him. Patriarch Theodosius (852-858) decreed that the Indian Church was obliged to send to the Patriarch cathedraticum and the letter of Communion only once in six years. 12 The Indian Christians had no difficulty in receiving these bishops from Persia, whom they considered as bishops of their own rite and nation. These bishops had jurisdiction all over India, and their seat was not assigned to a specific city, instead, they were called ‘metropolitan of all India’. The temporal administration of the Indian Church was governed by the Archdeacon. He himself acted with the assistance of the Palliyogam. Though the hierarchical structure of the Indian Church in the medieval period can be called a ‘metropolitan-archdeacon combination rule’. During the period there were two kinds of metropolitans in the Church of East; 1) electoral and 2) autonomous missionary metropolitans. Electoral metropolitans were carried the day-to-day administration of their local church, whereas the autonomous missionary metropolitans were the metropolitans in missionary lands that were far away from the patriarchal see. Indian metropolitan was of the second type. That means Indian metropolitans were fully autonomous.13 Even though he was the canonical head of the Indian Church, the Chaldean patriarch did not interfere in the internal administration of the Church. Because he respected the identity and autonomy of the Indian Church. Placid J. 10 Joseph Perumthottam, Mar Thoma Margam, 782-783. Placid J. Podipara, Hierarchy, 31. 12 Placid J. Podipara, Hierarchy, 31-32. 13 James Puliurumpil, Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church: A Historical Perspective (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2018), 88-89. 11 4 Podipara states, “According to tradition the Syro-Malabar Church was neither an extension nor an integral part either of the Persian or of the Chaldean Church. The Chaldean Church has always admitted the Apostolic origin of the Syro-Malabar Church.”14 The title of the Metropolitan of India was THE METROPOLITAN AND THE GATE OF ALL-INDIA (Metropolita v-thar'a d-kollah hendo). His authority was similar to that of a Catholicos. Though a catholicos was independent of the Patriarch, he was not.15 So we conclude that during the East Syrian period: “... the Church of St Thomas Christians was an autonomous metropolitan Church, headed by a metropolitan of All-India, appointed by the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch and governed by an indigenous Archdeacon of All-India, assisted by the general church assembly consisting of representatives of the clergy and the people of God." 16 3. Papal Primacy and Indian Church “Nineteen hundred years have passed since the Apostle came to India and in word and deed and utter self-sacrifice bore witness to Christ in your land.… During the centuries that India was cut off from the West …, the Christian communities formed by the Apostle conserved intact the legacy he left them.” 17 There were many attempts from the western writers to establish that St. Thomas Christians of India united with Rome only in the sixteenth century. But the Holy See corrected those mistakes by proclaiming that this Church was never separated from Rome. The above-quoted words are of Pope Pius XII which he gave in a radio message on the occasion of the 19th centenary celebration of the arrival of St Thomas in India and the 4th centenary of the death of St Francis Xavier. In these words of Pope Pius XII clearly states that the Indian Church conserved the faith which they received from the Apostle Thomas unbrokenly. 3.1. Doctrine of Papal Primacy in the Apostolic Period The Thomas Christians of India had no direct contact with the See of Rome till the sixteenth century. The question regarding the Papal primacy i.e., whether Thomas Christians of India had accepted the primacy of Roman see from the first century is the matter of study in this section. Though we don’t have any direct sources regarding the teaching of Apostle Thomas on Apostolic college and the primacy of Apostle Peter as the head of the college. We can assume that he had taught his disciples about the apostolic college and Jesus’s installation 14 Placid J. Podipara, Hierarchy, 35. Placid J. Podipara, Hierarchy, 32-33. 16 Paul Pallath, The Grave Tragedy of the St Thomas Christians and the Apostolic Mission of Sebastiani (Changanasserry: HIRS Publications, 2006), 6. 17 Pius XII, AAS 45 (1953) 96. 15 5 of Simon Peter (Kepha) as head of the apostles. We can notice his respect for Peter and Paul in naming his own successors after the apostles of Rome: Kepha in Cranganore and Paulose in Mylapore. After the apostolic period, the Indian Church kept its communion with the Eastern Churches with which they had a common apostolic origin. So, we can reach the hypothesis that, when the doctrine of the papal primacy was recognized in the eastern Christian centers, it was also acknowledged by the Indian Church.18 3.2. Doctrine of Papal Primacy in the Chaldean Period The Pseudo-Nicene canons of Mar Maruta of Maipherqat19 had great authority in the East Syrian Church. Two of these seventy-three canons were the basis for the East Syrians understanding of the canonical doctrine of papal primacy. These canons were in use in Malabar. Bishop Francis Ros found them in an ancient codex at Angamaly. So, the presence of Pseudo-Nicene canons in the ancient codex at Angamaly is the indication that the doctrine of papal primacy was part of the Indian Church's teaching. The Chaldeans claimed patriarchal rank for their Church based on letters from "western" fathers, among whom they listed Pope Caius. 20 3.3. John Marignolli OFM (1348/9) Another reference to the acknowledgment of Roman primacy by St Thomas Christians of India can be found in John Marignolli OFM's (1348/9) Asian voyage. He was sent as a legate by Pope Benedict XII to the Great Khan in 1338. On his return, he resided for about sixteen months at Quilon (1348/9). He was honored with great respect as the pope's legate by the St Thomas Christians. The leaders carried him in a palanquin. They erected a memorial monument of his visit, which displayed the pope's coat of arms. This way of receiving Marignolli with great respect by the Christians of St Thomas at Quilon is the best example of their awareness of the supremacy of the pope over their Church.21 18 Jacob Kollamparambil, The Sources of the Syro-Malabar Law, ed. Sunny Kokkaravalayil (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2015), 507 (hereafter cited as Sources). 19 Jacob Kollamparambil, Sources, 482-483. It is commonly belied that these canons were compiled by Mar Maruta of Maipherqat from the western sources (eg. Corpus canonum antiocheum) adapting them, to the particular needs of the East Syrian Church, and presented them to the Seleucian synod (410) in a pious fraud as though they were canons enacted by the Council of Nicaea. 20 Bishop Francis Ros translated this codex into Latin and sent the script to the Jesuit general for publication. We can have information regarding this from his letter to Fr John Alvarez, the Portuguese assistant to the Jesuit general, which he wrote on 23 November 1605. Jacob Kollamparambil, Sources, 508-9. 21 Jacob Kollamparambil, Sources, 518-20. 6 3.4. Joseph the Indian in Rome in 1502 In 1502 the famous Joseph the Indian visited Rome. Pope Alexander VI gave him an audience. During the meeting, the pope asked him about the authority of the catholicos of the East. Joseph's answer confirms the east Syrian understanding of the doctrine of papal primacy.22 3.5. East Syrian Understanding of the Doctrine of Papal Primacy In the canonical collections of the Indian Church which they had in common with the Persian Church, we can see their understanding of the doctrine of papal primacy. Like the number of the four parts of the globe, the Patriarchs are to be four, and their chief, the Patriarch of Rome as the Apostles have ordained. …A canon of the Church prescribes that the inferior must obey its superior and that the Roman Patriarch should include all under his obedience, seeing that he fills the place of Simon Peter.23 These canons express the correct eastern understanding of the doctrine of papal primacy i.e., first among the equals. In contrast to this, the western medieval concept of primacy appears to be a monarchical pattern. This concept is evident in the ecclesiastical policy followed by the Portuguese in India. This monarchic concept of authority reaches its hype during the Synod of Diamper. 4. Latin Period: Padroado – Propaganda Jurisdiction The centuries between sixteen and nineteen can be referred to as the Latin period for the St Thomas Christians of India. Because during this period they were under Latin jurisdiction. In the first phase of the Latin period, they were under Padroado jurisdiction. The second phase was of propaganda jurisdiction. In the third phase, two vicariates were erected exclusively for St Thomas Christians. 22 A. Vallavanthara, India in 1500 AD: The Narratives of Joseph the Indian (Mannanam: RISHI, 1984), 170, as cited in Jacob Kollamparambil, Sources, 521-22. Joseph the Indian replied: St Peter was the Pontiff in Antioch at the time of Simon Magus. Because there was no one who could oppose him they sent to supplicate St Peter to allow him to be transferred to Rome. Leaving a vicar of his (in Antioch) he came to Rome. And this is the one who is now called Catholica and he acts as the vicar of Peter. As regards how this Pontiff or Catholica is made, the twelve cardinals mentioned above gather in the province of Armenia where they elect their Pontiff. This authority, they say, they have from the Roman Pontiff. Here Joseph's knowledge of the Chaldean doctrine of Roman primacy is noticeable. 23 Xavier Koodapuzha, “Historical Overview of the Faith and Communion of St. Thomas Christians,” in Mar Thoma Margam, ed. Andrews Mekkattukunnel (Kottayam: OIRSI, 2012), 778. 7 4.1. Padroado Jurisdiction and the Loss of All India Jurisdiction The Padroado was a privilege granted by popes, that allowed the king of Portugal to invade, conquer, and subjugate all of the kingdoms in Africa and the East Indies. This gave the king ecclesiastical authority over his new subjects, allowing him to send good missionaries and establish new dioceses, parishes, and religious institutions. 24 The Padroado jurisdiction began in India by the erection of the diocese of Goa. Later Goa elevated to the metropolitan see by erecting two suffragan dioceses of Kochi in India and Malacca's in Malaysia. During the Portuguese time, the Chaldean bishops were Mar Jacob (1503-1552), Mar Joseph (15581569), and Mar Abraham (1569-1597). Following the death of Mar Abraham, the last Chaldean bishop, the Portuguese Padroado authorities made many organized attempts to latinize the St Thomas Christians. The most important was the Synod of Diamper, held from 20 to 26 June 1599 at Diamper, Udayamperur, convoked by Alexis de Menezes, archbishop of Goa. With the appointment of Francis Roz SJ (1599-1624) as the first Latin bishop of the St Thomas Christians and the abolition of the metropolitan status of Angamaly, by Pope Clement VIII (1592-1603) on 20 December 1599, the Latin jurisdiction over the St Thomas Christians formally began. The same Pope extended the Padroado jurisdiction over Angamaly on August 4, 1600. In 1608 Pope Paul V restored the Metropolitan rank of Angamaly in response to appeals from St Thomas Christians. During Francis Ros' reign, the See was moved from Angamaly to Cranganore. On December 20, 1610, India was partitioned geographically among the prelates of Goa, Cochin, Cranganore, and Mylapore. As a result, the Metropolitans of the St Thomas Christians' All-India authority were abolished.25 4.2. Propaganda Jurisdiction and Erection of Latin Vicariates From the Synod of Diamper (1599) until the Coonan Cross Oath (1653), Portuguese Padroado had exclusive jurisdiction in India. However, in the second half of the 17th century (1657), we find the existence of another jurisdiction in India under the guidance of the Congregation of Propaganda Fide. As a result, over the next two and a half centuries, the onefold St. Thomas Christians were divided between the two Catholic western Latin jurisdictions of Padroado and Propaganda. Padroado became weak owing to internal and external factors. Because of these political changes in Portugal, the Padroado sees of Cranganore and 24 Paul Pallath, Catholic Church in India, 41. These privileges and rights (also some obligations) were granted to the Portuguese kings through a number of papal decrees (bulls). By the papal bulls, Dum Diversas of June 18, 1452 and Romanus Pontifex of January 8, 1454, by Pope Nichola V (1447-1455) the Portuguese Padroado assumed its definite form. 25 Joseph Perumthottaam, Mar Thoma Margam, 785. 8 Cochin, to which the St Thomas Christians belonged, were suppressed in 1838. With this suppression, both St Thomas Christians and Latins came under the undivided Propaganda jurisdiction of the Vicar Apostolic of Malabar (subsequently named Verapoly). Because of its wide and inconvenient nature, Pope Pius IX separated the apostolic vicariate of Malabar into three in 1845: Quilon (South), Verapoly (Centre), and Mangalore (North). The vicariate of Verapoly included all St Thomas Christians. The Vicar Apostolic Mgr. Bernardino Bacinelli OCD of Verapoly appointed Fr. Kuriakose Chavara as vicar-general of the St Thomas Christians in 1861.26 However, at the request of the St Thomas Christians, the Holy See bestowed the title of 'Archbishop and Metropolitan' on the vicar apostolic of Malabar. The ancient archdiocese of Cranganore was suppressed on September 1, 1886. The vicariate apostolic of Verapoly was elevated to the status of a metropolitan archdiocese of the Latin Church, with Quilon as its suffragan see, and all Catholic St Thomas Christians became members of the archdiocese. 27 Another Portuguese Padroado bishop of Damuan was given the ancient title ‘Cranganore’ ad honorem. Furthermore, the Portuguese Padroado Archbishop of Goa was named ‘Patriarch of the East Indies.’ In sum, the St Thomas Christians were effectively deprived of its 'All-India' title as a result of all of these narrow-minded attitudes.28 4.3. Erection of Two Separate Vicariates Exclusively for St Thomas Christians On 20 May 1887 Pope Leo XIII separated the Eastern Catholics from the Latin Christians through the apostolic letter Quod iampridem and established two Syro-Malabar vicariates apostolic for them, Trichur and Kottayam. 29 On 23 August 1887 the Pope appointed Fr Charles Lavigne SJ, titular bishop of Milevum (1887- 1896), the vicar apostolic of Kottayam and Adolf Medlycott, titular bishop of Tricomia(1887-1896), vicar apostolic of Trichur. At the same time Pope appointed two native priests as the vicars general of the vicariates. Fr George Mampally was appointed vicar-general of Trichur and Fr Emmanuel Nidhiri vicar general of Kottayam.30 26 Placid J. Podipara, Hierarchy, 162. Paul Pallath, Constitution of Syro-Malabar Hierarchy: A Document Study (Changanassery: HIRS, 2014), 910 (hereafter cited as Constitution). 28 Joy George Mangalathil, All-India Jurisdiction, 97-98. 29 Leo XIII, Quod iampridem, ASS 29 (1886) 513-514. 30 Paul Pallath, Hierarchy, 175-6. 27 9 5. Syro-Malabar Period The Syro-Malabar31 period begins with the erection of separate vicariates for the St Thomas Christians and the appointment of native bishops. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century St Thomas Christians of India were under Latin jurisdiction. It is from 1896 the Syro-Malabar period began. 5.1. The Erection of Three Vicariates and the Appointment Native Bishops St Thomas Christians continued their effort to get bishops of their own rite and nation. On 28 July 1896 Pope Leo XIII with the apostolic letter Quae rei sacrae reorganized the territory and erected the three vicariates Apostolic of Trichur, Ernakulam, and Changanacherry. As vicars apostolic three native priests were appointed: John Menacherry, titular bishop of Parai and vicar apostolic of Trichur, Mathew Makil, titular bishop of Tralli and vicar apostolic of Changanacherry and Aloysius Pazheparambil, titular bishop of Tiana and vicar apostolic of Ernakulam. On 25 October 1896 in the cathedral church of Kandy in Sri Lanka the Apostolic Delegate Ladislao Michele Zaleski consecrated the first three Indian bishops. In order to fulfill the demand of the Sounthist (Knanaya) community for a separate vicariate, Pope Pius X by the Apostolic letter In Universi Christiani the vicariate of Kottayam was erected on 29 August 1911 and Vicar Apostolic Mathew Makil was transferred to the new vicariate of Kottayam. Thomas Kurialacherry was appointed as the vicar apostolic of Changanacherry. 32 5.2. Constitution of Syro-Malabar Hierarchy: The Erection of Eparchies and Exarchies On 1 May 1917 Pope Benedict XV erected the ‘Sacred Congregation for the Oriental Churches’ with the motu proprio Dei providentis. Till the erection of this congregation exclusively for the Oriental Churches, the Syro-Malabar Church was under the Congregation of Propaganda Fide. From 1917 onwards they came directly under this congregation. Even though Syro-Malabar Church had four vicariates and native bishops by the year 1911, they were not established to a hierarchy. After considering the progress of the Syro-Malabar Church under the native bishops, upon the recommendation of the Oriental Congregation, by the apostolic constitution Ramani pontifices33 on 21 December 1923, Pope Pius XI established The name ‘Syro-Malabar’ began to use to denote the St Thomas Christians in India from the nineteenth century. The term ‘Syro’ represents the East Syrian connection i.e., St Thomas Christians’ relationship with the Chaldean Church from whom they received their ways of worship. The later part of the name ‘Malabar’ denotes the geographical area in South India. 32 Paul Pallath, Constitution, 9-10. 33 Pius XI, apostolic constitution Ramani pontifices, AAS 7 (1924), 257-262. 31 10 Syro-Malabar hierarchy with Ernakulam-Angamaly as the Metropolitan See and Trichur, Changanassery and Kottayam as suffragan dioceses.34 Although the new Syro-Malabar hierarchy was de iure oriental, but its structure and hierarchical divisions of order and jurisdiction were identical to the Latin hierarchy. Roman Pontiff directly appointed the metropolitan and bishops. As in the Latin Church, it was mandatory for the Metropolitan to accept the pallium from Roman Pontif. The metropolitan and bishops possessed basically all of the rights, privileges, responsibilities, and obligations specified in the Latin Code (CIC 1917).35 During the period between 1950 to 1992, we could see the gradual growth of the SyroMalabar Church. During this period several dioceses and mission dioceses were erected. On 25 July 1950 Pope Pius XII bifurcated the eparchy of Changancherry and erected the eparchy of Palai by the apostolic constitution Quo Ecclesiarum.36 On 31 December 1953 the same Pope erected the eparchy of Tellichery for the Syro Malabar faithful who had immigrated to the northern part of Kerala.37 On 29 July 1956 Pope divided the archeparchy of Ernakulam and erected the eparchy of Kothamangalam.38 On 29 July 1956 Pope constituted Changanassery as the new Metropolitan See and Palai and Kottayam as suffragans. However, on 10 January 1959, his successor Pope John XXIII (1958 1963) issued the apostolic constitution Regnum Caelorum, which established the new province. 39 Between 1962 and 1972, six Syro-Malabar mission apostolic Exarchates were formed in central and northern India: Chanda, Sagar, Satna, Ujjain, Bijnor, and Jagadalpur.40 On1 March 1973 Pope Paul VI by the apostolic constitution Quanta Gloria bifurcated the eparchy of Tellicherry and erected the eparchy of Mananthavady as a suffragan of the archeparchy of Ernakulam.41 On 27 June 1974 the eparchy of Trichur was divided and the 34 James Puliurumpil, Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church, 245-246. Paul Pallath, The Catholic Church in India ,133. 36 Pius XII, apostolic constitution Quo Ecclesiarum, AAS 43 (1951) 147-150. 37 Pius XII, apostolic constitution Ad Christi Ecclesiam, AAS 46 (1954) 385-387. 38 Pius XII, apostolic constitution Qui in Beati Petri, V. Vithayathil, The Origin and Progress of the SyroMalabar Hierarchy, appendix VIII (Kottayam: OIRSI,1980), 129-131. This apostolic constitution is not found in AAS (hereafter cited as Origin and Progress). 39 John XXIII, apostolic constitution Regnum Caelorum, AAS 51 (1959) 580-581. 40 The apostolic decrees: Chanda - Qui benignissimo, in V. Vithayathil, The Origin and Progress, Apendix XI, 135; Sagar - Quo aptius, AAS 61 (1969) 20-21; Satna In more, AAS 61 (1969) 21-22; Ujjain - Apostolicum munus, AAS 61 (1969) 23-24; Bijnor- In beatorum apostolorum similitudinem and Jagadalpur- Inc Gentes. AAS 64 (1972) 416-419. 41 Paul VI, apostolic constitution Quanta gloria, AAS 65 (1973) 228-229. 35 11 same Pope created the eparchy of Palaghat in the ecclesiastical province of Ernakulam. 42 Pope elevated the six apostolic exarchates, Chanda, Sagar, Satna, Ujjain, Bijnor and Jagadalpur to the rank of eparchies on 26 February 1977 and erected the new mission eparchy of Rajkot.43 On the same day the Pope divided the archeparchy of Changanacherry, creating the eparchy of Kanjirappally as its suffragan.44 Pope bifurcated the eparchy of Trichur by the apostolic constitution Trichuriensis eparchiae on 22 June 1978 and established the eparchy of Irinjalakuda as a suffragan of the see of Ernakulam.45 Thus, nine eparchies were established during the Pontificate of Pope Paul VI 1963-1978) for the St Thomas Christians of India. We could also see a significant progress in the Syro-Malabar Church during the Pontificate of Pope John Paul II (1978-2005). On 11 September 1984 he erected the eparchy of Gorakpur by the apostolic constitution Ex quo divinum.46 On 28 April 1986 as a suffragan to Ernakulam the eparchy of Thamarasserry was constituted.47 The eparchy of Kalyan was erected on 30 April 1988 with special consideration for the pastoral care of the Syro-Malabar immigrants in Bombay, Pune Nasik region.48 5.3. Syro-Malabar Church as Major Archiepiscopal Church On 16 November 1992 Pope John Paul II nominated Mar Antony Padiyara, the metropolitan archbishop of Ernakulam as the first Major Archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church. On 16 December 1992 by the apostolic constitution Quae maiori Pope constituted Syro-Malabar Church as a Major Archiepiscopal Church under the title ErnakulamAngamaly. Even though, it was stated in the apostolic constitution Quae maiori that “along with all the rights and duties incumbent on the same in terms of the Sacred Canons of the Eastern Churches”, all that is concerned with the Episcopal elections and the liturgical order was reserved to the Roman Pontiff. 49 Taking into account the lack of unity among the bishops and the identity crisis within the Syro-Malabar Church the Holy Father did not grant all the powers to this Church which 42 Paul VI, apostolic constitution Apostolico requirente, AAS 66 (1974) 472. The 7 apostolic constitutions can be found in AAS 69 (1977) 241-248. 44 Paul VI, apostolic constitution Nos, Beati Petri, AAS 69 (1977) 249-250. 45 Paul VI, apostolic constitution Trichuriensis eparchiae, AAS 70 (1978) 447-448. 46 John Paul II, apostolic constitution Ex quo divinum, AAS 1976 (1984) 945-946. 47 John Paul II, apostolic constitution Constat non modo, AAS 78 (1986) 908. 48 John Paul II, apostolic constitution Pro Christi fidelibus, AAS 80 (1988) 1381-1382. 49 John Paul II, apostolic Constitution Quae maiori, AAS 85 (1993) 398-399. 43 12 is stipulated in the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches and some peculiar norms were established ad tempus. He reserved certain functions to a special Delegate. 5.4. Juridical Perfection of Syro-Malabar Church and the Synod of Bishops In the Eastern tradition, the supreme authority of a patriarchal or Major Archiepiscopal Church is the Synod of Bishops convoked and presided over by the patriarch or Major Archbishop (CCEO c.152). The synod of bishops juridically comes into being by the very fact of the elevation of a Church to the patriarchal or major archiepiscopal status. The patriarch or major archbishop can convoke a synod of bishops at any time after his coronation and the reception of ecclesiastical communion from the Roman Pontiff. Considering the situation in the Syro-Malabar Church, Holy Father was granted these faculties to convoke and preside over the synod of bishops to papal delegate. After the installation of Mat Antony Padiyara (20 May 1993) the first Major Archbishop, the first session of synod of bishops was conducted on 20 to 25 of May 1993. During the synod the elections of the members of permanent synod and superior tribunal were taken place. The synodal commissions for particular law, liturgy, ecumenism, catechism, evangelization, pastoral care of migrants and catholic doctrine were formed. In the second session of the synod which was held from 22 November to 4 December the synodal statutes were approved. During the third session (7 to 23 November 1994) the statutes of the permanent synod and the superior tribunal were approved. 50 On 18 December 1999 Pope John Paul II appointed Varkey Vithayathil the then apostolic administrator as the Major Archbishop of Syro-Malabar Church. In the decree of the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, we read: “decided to elevate His Excellency the Most Reverend Varkey Vithayathil,… to the dignity and Office of the Major Archbishop of Ernakulam-Angamaly, … with all the rights, honors and privileges of the Office of the Major Archbishop according to the norms of the Code of Canons of the Oriental Churches and the norms of the Holy See.”51 During the time of the second Major Archbishop the Synod of SyroMalabar Church was given full powers. On the proposal of Congregation for the Oriental Churches Pope John Paul II revoked the reservation and with the decree of the Congregation published on 3 January 2004 the decision came into effect. With this decree, Syro Malabar Church has become a fully-fledged and juridically perfect major archiepiscopal Church according to the norms of the Eastern Code. 50 Paul Pallath, The Catholic Church in India, 148-149. The Decree of the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, Prot. N. 140/99, Synodal News, vol. 7, nos. 1& 2 (December 1999) 99. 51 13 5.5. The Erection of New Metropolitan Provinces and Eparchies On 18 May 1995, Pope John Paul II established the metropolitan provinces of Trichur and Thalassery, raising the said eparchies to metropolitan status.52 The Eparchies of Thucklay (11.11.1996), Belthangady (26.5.1999), Adilabad (16.7.1999), Chicago in USA (13.3.2001) and Idukki (19.12.2002) were erected.53 With the consent of the synod of bishops and having consulted the Apostolic See, on 9 May 2005 Mar Varkey Vithayathil, the major archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church elevated the eparchy of Kottayam to the rank of a metropolitan see. On 21 August 2007 Cardinal Varkey Vithayathil, Major archbishop of the SyroMalabr Church erected the eparchy of Bhadravati as a suffragan of the archdiocese of Thalassery. On 15 January 2010, bifurcating Mananthavady, erected the eparchy of Mandya, as suffragan of Thalassery in Karnataka. On the same day bifurcating Palakad, Ramanathapuram was constituted in Tamil Nadu as suffragan of Thrissur. On 6 March 2012, the eparchy of Faridabad was erected in North India. On 23 December 2013 Melbourne, on 6 August 2015 Canada (exarchate), and on 28 July 2016, Great Britain were erected as SyroMalabar dioceses outside India. With the document Mystici unitas the diocese of Hosur was erected on 9 October 2017 by Pope Francis. 5.6 The Erection of the Diocese of Shamshabad and All India Jurisdiction With the document, Tamquam viti palmites Pope Francis erected the diocese of Shamshabad on 9 October 2017. It reads: “We erect and constitute the new eparchy under the name of Shamshabad, out of all the territories of India where at present the eparchial jurisdiction for the Christian faithful of the same Syro-Malabar Church is wanting.”54 Through the letter Varietas ecclesiarum which is addressed to the bishops of India dated 17 October 2017 Holy Father Pope Francis says that all the new and old circumscriptions of the SyroMalabar Church in India “are entrusted to the pastoral care of the Major Archbishop of Ernakulam-Angamaly and to the Synod of Bishops of the Syro-Malabar Church, according to 52 John Paul II, apostolic constitutions Ad augendum spirituale (Trichur) and Spirituali bono (Tellicherry), AAS 87 (1995) 984-986. 53 John Paul II, apostolic constitutions Apud Indorum, AAS 89 (1997) 745-746 (Thuckalay); Cum ampla, AAS 91 (1999) 1025-1026 (Belthangady); Ad aptius, AAS 91 (1999) 1031 (Adilabad); Congregatio pro, AAS 93 (2001) 423-424 (Chicago); Maturescens Cattolica, AAS 95 (2003) 381-382 (Idukki). 54 Synodal News, No.1-2, vol. 25 (2017) 191-192. 14 the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.”55 With the erection of the Eparchy of Shamshabad and the introduction of this letter, we could assume that the proper territory of the Syro-Malabar Church is now extended to the other parts of India where there is no SyroMalabar eparchy or exarchy had been erected. Thus, the once lost ‘All-India Jurisdiction’ is now restored. Conclusion “I love your Church because I know her history.” - Cardinal Eugene Tisserant These words of Cardinal Eugene Tisserant always place a great challenge before every Syro-Malabar Christian. Through this seminar paper, we were making a short historicojuridical study on the hierarchical authority of the Indian Church. This study was focused on the historical evolution of the hierarchy of Syro-Malabar Church. While going through history we realize the great effort that has taken by the St Thomas Christians to upheld the true catholic faith even in the midst of persecutions and religious suppression from the part of Padroado. Their great reverence towards the see of Apostle Peter and his successors is appreciable. The great love and respect that the Chaldean Patriarchs had towards their sister Church in India are praiseworthy. Because their presence re-energized the Indian Church. Through this study, we realize the serious responsibility of protecting and nourishing the authentic Oriental nature and identity of the Syro-Malabar Church. Thou, a stable hierarchical structure has established during the course of time there is more to nurture in the fields of liturgy, theology, spirituality, and discipline. 55 Francis, apostolic letter to the Bishops of India, Varietas ecclesiarum, 7. Accessed on February 14, 2022, https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/letters/2017/documents/papa-francesco_20171009_vescoviindia.html. 15 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Roman Documents Francis. Apostolic letter to the Bishops of India, Varietas ecclesiarum. Accessed on February 14, 2022, https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/letters/2017/documents/papafrancesc o_20171009 _vescovi-india.html. John Paul II. Apostolic constitution Constat non modo. AAS 78 (1986). ________. Apostolic constitution Ex quo divinum. AAS 1976 (1984). ________. Apostolic constitution Pro Christi fidelibus. AAS 80 (1988). ________. Apostolic Constitution Quae maiori. AAS 85 (1993). ________. Apostolic constitutions Ad augendum spirituale (Trichur) and Spirituali bono (Tellicherry). AAS 87 (1995). ________. Apostolic constitutions Apud Indorum. AAS 89 (1997) 745-746. ________. Apostolic constitutions Cum ampla. AAS 91 (1999) 1025-1026. ________. Apostolic constitutions Ad aptius. AAS 91 (1999) 1031. ________. Apostolic constitutions Congregatio pro. AAS 93 (2001) 423-424. ________. Apostolic constitutions Maturescens Cattolica. AAS 95 (2003) 381-382. John XXIII, apostolic constitution Regnum Caelorum. AAS 51 (1959) 580-581. Leo XIII. Apostolic constitution Quod iampridem. ASS 29 (1886) 513-514. Paul VI. Apostolic constitution Apostolico requirente. AAS 66 (1974) 472. ________. Apostolic constitution Nos, Beati Petri. AAS 69 (1977) 249-250. ________. Apostolic constitution Quanta gloria. AAS 65 (1973) 228-229. ________. Apostolic constitution Trichuriensis eparchiae. AAS 70 (1978) 447-448. Pius XI. Apostolic constitution Ramani pontifices. AAS 7 (1924), 257-262. Pius XII. Apostolic constitution Ad Christi Ecclesiam. AAS 46 (1954) 385-387. ________. apostolic constitution Quo Ecclesiarum. AAS 43 (1951) 147-150. Congregation for the Oriental Churches. Quo aptius. AAS 61 (1969) 20-21. ________.In more, AAS 61 (1969) 21-22. ________.Apostolicum munus, AAS 61 (1969) 23-24. ________.In beatorum apostolorum similitudinem. AAS 64 (1972) 416-419. ________.Inc Gentes. AAS 64 (1972) 416-419. 16 2. Books and Articles Kollamparambil, Jacob. The Sources of the Syro-Malabar Law. Edited by Sunny Kokkaravalayil. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2015. Koodapuzha, Xavier. “Historical Overview of the Faith and Communion of St. Thomas Christians.” In Mar Thoma Margam: The Ecclesial Heritage of the St Thomas Christians, edited by Andrews Mekkattukunnel, 770-780. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2012. Mangalathil, Joy George. “The Metropolitan and Gate of All India: A Proud Legacy of the St Thomas Christians.” In The All-India Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church, Qanona 6, 75-105. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2019. Mekkattukunnel, Andrews, ed. Mar Thoma Margam: The Ecclesial Heritage of the St Thomas Christians. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2012. Pallath, Paul. Constitution of Syro-Malabar Hierarchy: A Document Study. Changanassery: HIRS, 2014. ________. The Catholic Church in India. Rome: Mar Thoma Yogam, 2005. ________. The Grave Tragedy of the St Thomas Christians and the Apostolic Mission of Sebastiani. Changanasserry: HIRS Publications, 2006. Perumthottam, Joseph. “Historical Evolution of the Hierarchy of the Syro-Malabar Church.” In Mar Thoma Margam: The Ecclesial Heritage of the St Thomas Christians, edited by. Andrews Mekkattukunnel, 781-793. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2012. Podipara, Placid J. Four Essays on the Pre-Seventeenth Century Church of the Thomas Christians of India (Malabar). Changanassery: Sandesanilayam Publications, 1997. ________. The Hierarchy of the Syro-Malabar Church. Alleppey: Prakasam Publications, 1976. Puliurumpil, James. Jurisdiction of the Syro-Malabar Church: A Historical Perspective. Kottayam: OIRSI, 2018. Schaff, Philip. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Vol 14, The Seven Ecumenical Councils. Grand Rapids, Michigan: WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994. Vallavanthara, A. India in 1500 AD: The Narratives of Joseph the Indian (Mannanam: RISHI, 1984). Vithayathil, V. The Origin and Progress of the Syro-Malabar Hierarchy. Kottayam: OIRSI,1980. 17