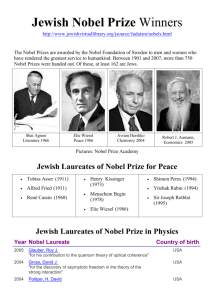

Agnon’s Tales of the Land of Israel, Edited by Jeffrey Saks and Shalom Carmy, Yeshiva University Center for Israel Studies Series.2021. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications. 209 pp. Naomi Sokoloff University of Washington In 1966, S.Y. Agnon won the Nobel Prize for literature. In 2016, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of that occasion, Yeshiva University held a symposium in honor of Modern Hebrew literature’s most acclaimed author. The volume that emerged from the conference, Agnon’s Tales of the Land of Israel, offers eleven essays. All of them focus on narratives dealing with the State of Israel, the Yishuv, and/or themes of Holy Land and Exile. The novel T’mol Shilshom [Only Yesterday] holds pride of place, drawing central attention in four of the essays. The collection opens with the compelling question, who reads Agnon? Shalom Carmy shares reflections on his own experience. As a young man he preferred Christian writers, such as T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, C.S. Lewis, and Graham Greene. However, as he matured, he found that Agnon’s appeal grew. In contrast to literature that dealt in crisis or melodrama, Agnon’s work presented “indolent confusions” – material that was less exciting, but more likely to foster “mature religious flourishing”. Carmy concludes that Agnon inspires: as a moral psychologist, a committed Jewish artist, and a chronicler who commemorates the Jewish past. Carmy’s comments set the stage for the other essays in the volume. His piece implies the question, whose work appears here? Who are these readers? What is their orientation toward Agnon, toward religious heritage, toward reading itself? One answer is that the contributors – a stellar line-up of Agnon scholars – are for the most part associated with Jewish academic institutions, such as Yeshiva University, JTSA, HUC-JIR, and more. They all display extensive knowledge of traditional Judaic texts. For example, in an interview with Jeffrey Saks, Avraham Holtz outlines a longstanding project of his, an annotated edition of T’mol Shilshom; he notes that one of its primary aims is to explain the novel’s many references to Biblical and rabbinic sources. Saks, in an essay of his own, considers Agnon’s Nobel speech in light of Psalm 137. Both texts, he observes, express yearning for Zion and emphasize literature as HHE 24 (2022) Reviews “balm for pain,” compensation for the loss of past tradition. Saks highlights storytelling as an important motif throughout Agnon’s work, and he makes the case that literary creativity has long been a Jewish response to catastrophe. Wendy Zierler considers religious themes as she compares Agnon’s “Tehilla” (1950) to Dvora Baron’s “Savta Hanye” (1909), another story featuring a saintly grandmother whose name connotes prayer (tkhine). Zierler’s analysis is accompanied by her translation of Baron’s story. Alan Mintz’ chapter is notable in part because it directly addresses the question of readership and religious focus. This piece surmises that many future Agnon readers will be Americans, given that Agnon’s work bridges “the world of tradition and the world of modernity,” eschewing binaries and so speaking persuasively to Diaspora Jews. I am not entirely swayed by this argument; many Israeli Jews in recent years have moved beyond religious/secular divides. It is certainly true, though, that Americans have contributed meaningfully to Agnon studies. Mintz is one of the most esteemed among them. His essay here deftly calls attention to the pull of Diaspora on Agnon’s imagination. It develops the claim that tales in Ir Umelo’ah [A City in Its Fullness] evolved in reaction against Ben Gurion’s nativist Zionism and expressed nostalgia for the religious milieu of Eastern Europe in days gone by. Several other essays in this book concentrate on tensions between religious and secular values in Zionist contexts. Zafrira Lidovsky Cohen reads “Agunot” (1908) as a story reflecting concerns from the period of the Second Aliya – specifically, negation of the Diaspora and of old-world culture. Moshe Simkovich, for his part, assesses “The Covenant of Loss” (1925) by comparing Agnon’s thoughts on Aliya with the ideas of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook. Steven Fine discusses Agnon’s “Tale of the Menorah” (1956), a story about recovering lost sacred artifacts, as indicative of tensions between Jewish religious authorities and secular governmental ones in the State of Israel. In so doing, Fine comments on both a long history of Jewish cultural adaptation in Europe and on a mid-20th century menorah craze in Israel (where, he notes, images of menorahs were everywhere, from “soap and insurance to postage stamps and building facades”). Hillel Halkin, in his essay, looks closely at T’mol shilshom as a novel about loss of balance. The protagonist, of the novel, Yizhak Kummer, famously goes to extremes as he gravitates first to secular values, then religious ones. Halkin contends that Agnon, himself, strove 2 HHE 24 (2022) Reviews instead for balance: in religious observance and also in his art. Agnon crafted innovative prose that sustains the richness of tradition. Even as Hebrew in the 20th century expanded rapidly (developing into a spoken language) and shrank dramatically (losing many of its earlier, sacred strata), Agnon refused to accept rupture with the past. He wanted both modernity and continuity. In another essay that highlights Agnon’s views vis-à-vis linguistic revival, Laura Wiseman reads the satirical piece “Orange Peel” (1939) as a cautionary tale on uses and abuses of the Hebrew language and its sacred and secular components. The volume concludes with Shulamith Z. Berger’s account of a visit by Agnon at Yeshiva University in 1967. That event took place a year after the awarding of the Nobel Prize, and in the midst of the June war. In his speech for the Swedish Academy, Agnon had spoken intently of Jerusalem as his home; in New York he was preoccupied with news of the war and especially with the battle for Jerusalem. Commenting on these points, Berger’s essay links Yeshiva University directly with the central focus of Saks and Carmy’s edited volume: the importance of Zion in Agnon’s thinking. Agnon’s writing can be and has been approached from many perspectives. His art continues to fascinate, to exert influence on a range of readers and writers, to elicit all manner of interpretations. Recent approaches have included new psychoanalytic angles as well as post-colonial, anthropological, and archival ones, plus considerations of gender studies, critical animal studies, computational analysis, and more. Agnon is for everyone. Still, one of the strengths of Agnon’s Tales of the Land of Israel is that the contributors, with their deep knowledge of Judaism and traditional texts, bring a special erudition to their readings. They apply to their work a sensibility close to Agnon’s own heart. In short: readers, do not expect this collection of essays to provide a comprehensive update on Agnon studies. But, do know that the volume contains excellent work. This book is highly informative and a rewarding read. 3