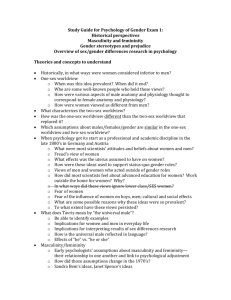

Benevolent Sexism & Collective Action: A Social Psychology Study

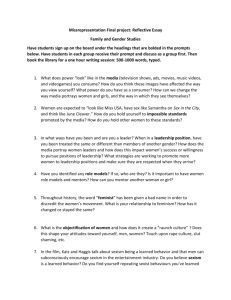

advertisement