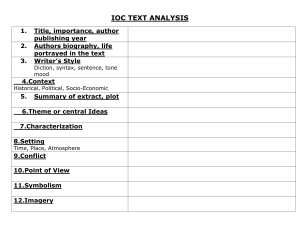

IOUEC-XXXIIU2 Annex 3 Paris, 27 March 2000 Original: English INTERGOVERNMENTAL Thirty-third OCEANOGRAPHIC (of UNESCO) COMMISSION Session of the IOC Executive Council Paris, 20-30 June 2000 Apenda Item: 3.4 EXTERNAL EVALUATION REPORT The External evaluation of IOC was implemented by the team of external experts during 1999-2000 with the goal to provide an objective view of the capacities and capabilities of IOC as an intergovernmental organization and a dedicated UN mechanism for carrying out the mission assigned to the Commission by the Statutes. The product of the evaluation team was the external evaluation report which was presented to the Director-General in March 2000. The report is submitted to the Executive Council for information and discussion of follow-up actions. The report will also be available for discussion during the 160* Session of the UNESCO Executive Board in the fall of 2000. SC-2000KONF.204KLD.7 UNESCO AND THE OCEANS - AN EVALUATION INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC FINAL REPORT John W Zillman John G Field Elie Jarmache February 2000 OF THE COMMISSION ... 111 Mr Koichiro Matsuura Director General United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, Place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris Cedex 07 FRANCE Dear Mr Matsuura On behalf of the External Evaluation Team, I am pleased to submit the Team’s Evaluation Report on the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO. The Team was appointed by your predecessor in March 1999 to provide an independent external evaluation of the IOC in the wake of the 1998 International Year of the Oceans. We found an organization that is unique in UNESCO and in the UN system and of which UNESCO can feel extremely proud. It is performing a vitally important role in international earth system science - effectively a role in need of specialised agency status and resources and one which will assume greatly increased importance in the years ahead. We believe UNESCO is faced with an unprecedented window of opportunity to provide the IOC with the institutional and financial support which will enable it to deliver enormous benefits to society from its investment in the science of the oceans during the second half of the twentieth century. With the help of much valuable advice from many stakeholders, we have suggested how this might be done. We believe UNESCO is uniquely placed to provide the international leadership that is urgently needed at this time and we commend our proposed strategy for your consideration. It has been a pleasure to carry out this evaluation with the support and assistance of the Executive Secretary of the IOC, Professor Bernal, and his dedicated staff. It was a rare privilege, in reviewing an international organization, to find a Secretariat whose professionalism, dedication and practical achievement were so appreciated by Member States: even in the face of Members’ abiding frustration that so much more needs to be done. We believe the small IOC Secretariat to be the vital professional nucleus for a truly outstanding UNESCO contribution to the good of humanity through marine research and operational oceanography in the twenty-first century. Yours sincerely J W Zillman (Team Leader) on behalf of the Evaluation Team John G Field Elie Jarmache John W Zillman February 2000 V UNESCO AND THE OCEANS - AN EVALUATION OF THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii-xii 1 INTRODUCTION Purpose of this Report 1.1 The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission 1.2 The Evaluation 1.3 Conclusion and Recommendation 1.4 2 IOC STRUCTURE AND OPERATIONS The Evolution of the IOC as an International Agency 2.1 Role and Statutes 2.2 Governance 2.3 National Representation 2.4 Cooperation with Other Organizations 2.5 Planning and Evaluation 2.6 Conclusions and Recommendations 2.7 8 8 10 10 12 12 15 15 3 THE IOC PROGRAMME Overall Impressions 3.1 Ocean Science 3.2 Operational Observing Systems 3.3 Ocean Services 3.4 Cross-cutting Activities 3.5 Regional Activities 3.6 Conclusions and Recommendations 3.7 17 17 18 20 23 25 26 27 4 ADMINISTRATION AND RESOURCES The IOC Secretariat 4.1 The WESTPAC Office 4.2 Resources and Resource Management 4.3 Conclusions and Recommendations 4.4 29 29 32 32 34 5 SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE Conclusions 5.1 Recommendations 5.2 Lessons Learned 5.3 37 38 41 44 vi APPENDIXES A B C D E F G H I J K List of Acronyms A Brief History of the IOC IOC Statutes IOC Organization and Programme Structure IOC Secretariat IOC Resources and Budget Terms of Reference and Membership of the Evaluation Team Questionnaire to IOC Member States Summary Analysis of Responses to Evaluation Questionnaire The Evaluation of WESTPAC Economic Evaluation and IOC Activities 47 51 61 67 69 71 77 79 85 87 91 vii UNESCO AND THE OCEANS - AN EVALUATION OF THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The world’s oceans represent a unique global commons and vital life support system for humanity in the twenty-first century. They are arguably the most bountiful yet the most threatened natural resource of the planet. Their vastness belies their fragility and the important and wide-ranging services they render to the global community contrast sharply with the limited extent to which they have yet been properly observed and understood. The oceans provide the physical linkage and the primary mode of transportation of natural resources and manufactured goods between maritime nations. Their evolution on timescales from days to millennia is a major determinant of the world’s weather and climate and they provide the key to better understanding of society’s vulnerability to natural disasters and the impacts of inadvertent human interference with the natural systems of the planet. More than half of the earth’s surface consists of international ocean, demanding intergovernmental coordination of national programmes for its study and management. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO is uniquely placed to play this pivotal role. In particular, recent scientific and technological advances, outlined below, provide UNESCO with a window of opportunity to coordinate a new generation of services needed for the oceans, much as already exists for the atmosphere. The 1980s and 1990s have seen a revolution in global marine science and technology. It has brought the ability to provide daily global pictures of the dynamics of ocean surface physics, chemistry and biology from satellites. This capacity is coupled with new technologies for automated sensing at and below the ocean surface, feeding information into databases and ocean models in real time. The information technology and computing revolution pose exciting challenges for the IOC to coordinate international distribution and use of massive quantities of three-dimensional data for operational and research applications. These applications include forecasting El Nifio and other climate oscillations as well as waves, currents and storm surges, and managing fisheries, marine pollution, harmful plankton blooms, offshore oil and gas extraction, ocean mining, shipping and coastal zone development. If these opportunities are to be grasped and if society is to continue to draw on the vital sustenance and services provided by the oceans and maintain the habitability and quality of life on the planet, a vastly increased effort on monitoring, understanding, predicting and protecting the oceans must be recognised and embraced as a global imperative for the twenty-first century. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) was established under the auspices of UNESCO in 1960 to provide the Member States of the United Nations (UN) with an essential mechanism for global cooperation in the study of the ocean - much as was already being provided by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) for the atmosphere - but with the added ... Vlll responsibility of serving also as a common mechanism for essential global coordination amongst all the UN agencies and programmes with responsibility for marine affairs. In order to perform its vital cross-sectoral and cross-agency responsibilities and provide an efficient and effective mechanism for drawing on the expertise of the nongovernmental scientific community, the Twenty-fourth Session ofthe General Conference in 1987 provided the IOC with functional autonomy within UNESCO. The basic mission of the IOC is defined in Article 2 of its statutes which states that “The purpose of the Commission is to promote international cooperation and to coordinate programmes in research, services and capacity building, in order to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas and to apply that knowledge for the improvement of management, sustainable development, the protection of the marine environment, and the decision making processes of its Member States.” The Evaluation This external evaluation of the IOC was commissioned by the Director General in 1998 as part of the overall evaluation programme of UNESCO. Its general goal was to provide an objective view of the capacities and capabilities of the IOC as an intergovernmental organization and a dedicated UN mechanism for carrying out the mission assigned to it by its statutes. It thus embraced an evaluation of: . The structure and operation of the IOC as an intergovernmental organization. . The IOC Programme as part of the overall Science Programme of UNESCO. . The role of the IOC Secretariat in support of the work of the Commission as both an intergovernmental organization and a programme of UNESCO. The evaluation was carried out by a team of three external experts with wide experience in oceanography and its sister sciences at both the intergovernmental and nongovernmental levels including leadership of the major scientific organizations with which the IOC works closely in several of its international cooperative scientific programmes. The Evaluation Team drew on questionnaire assessmentof views from the Member States of the Commission, direct input from IOC’s partner agencies and programmes within UNESCO and the broader UN system, extensive opinion sampling from leaders of the international marine science community, consultation with IOC staff in Paris and in its Regional Offices as well as detailed study of IOC documentation and reports. It also drew on the findings of consultant studies on the economic and social value of IOC programmes and its members observed recent sessions of the IOC governing bodies. The Evaluation Team met formally in Paris on 22-23 June and 710 December 1999 and two members of the Team reviewed the operation of the WESTPAC (Western Pacific Sub-Commission) Office of the IOC in Bangkok on 2-4 December 1999. The main findings of the Evaluation Team are summarised below as a basis for the Team’s general conclusions and major recommendations which follow and which are elaborated in more detail in the full report. IOC Structure and Operations The Evaluation Team found that the overall situation of the IOC as an autonomous intergovernmental organization within UNESCO is widely regarded as appropriate for the ix performance of its mission and that its operation is seen as generally efficient and effective by most of the countries, organizations and individuals who are closely familiar with its work. The IOC statutes, as most recently approved by the Thirtieth Session of the General Conference of UNESCO in November 1999, were developed through an extensive process of internal evaluation and consultation and should provide an appropriate framework for the governance of the Commission and for ensuring its accountability to its Member States over the next decade. The IOC’s structures for working in collaboration with other UN system agencies and programmes are generally well regarded and there is a high level of expectation in the marine community for the newly established IOC-WMO Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM) as a vehicle for streamlined coordination at intergovernmental level between international programmes in oceanography and meteorology and as a prototype for broader cooperation in the earth and environmental sciences between UNESCO and WMO and within the UN system generally. Collaboration between the governing bodies of the IOC and its counterparts in the nongovernmental marine science community, especially the ICSU (International Council for Science) Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR) and the ICSU World Data Centres (WDCs) Panel is also seen as exemplary. The Evaluation Team believes, however, that there is scope for improved strategic planning and management in IOC as it focusses on the major challenges of the next few years, both within the context ofthe UNESCO medium-term strategy and more broadly. A much greater effort is needed on increasing the visibility and understanding of the work of the IOC within UNESCO and the larger UN system. The Commission is, in effect, charged with fulfilling the responsibilities of a UN specialised agency for the oceans but currently lacks the resources and the international profile to carry out that role. It will need the strong support of both its parent UNESCO and its partner agencies in meeting this challenge over the next decade. The Evaluation Team found that particular effort is needed to strengthen the role of National Committees for the IOC (or other appropriate national coordination mechanisms) in many countries. Stronger links are also needed to the National Commissions for UNESCO as well as with the broader national marine coordination mechanisms which operate in most maritime countries. The IOC Programme The overall programme of the IOC has evolved over the past 40 years from an initial focus on a number of geographically and discipline-specific research projects into an integrated framework for observing, understanding, modelling and managing the health ofthe oceans and their interface with the hydrological, coastal and atmospheric processes which govern the behaviour of the total earth system. One of the inevitable results of this evolution and the increasing need for coordination with other disciplines and other programmes within and external to UNESCO has been that the work programme of the IOC has become too thinly spread and sub-critical in many areas. The recent restructuring of the overall IOC Programme into the three major areas of: . ocean sciences, . operational observing systems (essentially the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and its coordination with other international environmental observing programmes), . ocean services, X with the former Training, Education and Mutual Assistance (TEMA) and Regional Programmes now managed as cross-cutting activities, is considered to be timely and appropriate for the current stage of development of the Commission. The Evaluation Team was concerned, however, at the generally poorly defined programme structure and the lack of readily accessible information on programme and project budgets and expenditures, apparently due in large measure to the lack of appropriate programme costing and management information systems and support staff. The Team shared a widely-felt need for the IOC Programme to be thoroughly reviewed and rationalised within the new overall programme structure with significant streamlining and refocussing of programmes and projects and adoption of a much more strategic approach to programme planning, budgeting, management and performance evaluation with the support of modem management infrastructure. The Evaluation Team found a significant polarisation of views on the IOC Regional Programme. On the one hand, Member States look to the IOC to facilitate and accelerate what they see as essential and urgent action on regional problems but, on the other, they recognise that the focussing of resources at the regional level runs the risk of diverting attention from the global programmes on which they are also heavily dependent. Ultimately, this must be addressed as an issue of prioritisation by the Members and governing bodies of the IOC within the total resources available for implementation of the IOC Programme. IOC Administration and Resources The Evaluation Team found a widespread appreciation among Members and the scientific community for the professionalism, dedication and efficiency of the Executive Secretary and the staff of the IOC Secretariat. This was, however, coupled with almost universal recognition that the Secretariat is far too small and thinly spread to carry out the enormous range of functions and tasks that Members expect of it in support of the work of the IOC governing bodies and coordination of the implementation of the IOC Programme. The staffing situation in the IOC Secretariat has reached crisis point but remedies appear to be potentially available within the management flexibility of UNESCO and the marine agencies of Member States who stand to benefit from the improved performance of the IOC Programme. For the Secretariat to adequately support the IOC role, not just as an important science programme of UNESCO but also, in effect, as the UN specialised agency for the oceans, and to deliver the benefits to UNESCO Member States from its partnership with other marine-oriented programmes and agencies of the UN system, it is essential and urgent that the present core professional staffing be at least doubled from 9 to 18 Regular Budget funded posts with appropriate associated administrative support. Experience has shown that, given a critical mass of core funded experts for overall leadership of the IOC Programme, the multiplier effect and reciprocal benefits to Members from limited-term (ie several months to several years) secondments into the specialist programme areas of the IOC Secretariat are extremely large. The Evaluation Team believes that a strengthened programme of expert secondments to the IOC Secretariat to complement the proposed doubling of the core professional staff, would enable UNESCO and IOC Member States to reap enormous benefits from the IOC Programme over the next decade. The Evaluation Team has reluctantly concluded that, despite the clear and immediate benefits of decentralised IOC Offices in the regions where they already exist and the strongly felt need for a local presence of the Secretariat in other regions, the IOC Secretariat is, at present, much too small to support separate offices in all regions. These would only be viable if a significant number xi of Members States are prepared to follow the admirable example of those who have already contributed expert staff on long-term secondment to work as IOC representatives or programme experts within the regions. It is clear that the inadequacy of the overall staffing and resource levels at the disposal of the Commission and its Executive Secretary represent the most serious impediment to realisation of the immense potential benefits of the IOC and its programmes over the next decade. The Evaluation Team is strongly of the view that, given the enormous opportunities that are opening up as a product of the international scientific collaboration amongst IOC and its partners in the final decades of the twentieth century, the small additional investment now required by UNESCO and IOC Member States would repay itself many-fold to UNESCO itself and to all those countries and social and economic sectors whose future prosperity, welfare and quality of life are so clearly linked to better understanding and management of the coasts and oceans. Conclusions and Major Recommendations The information and evidence available to the Evaluation Team leads it to the conclusion that the IOC is performing a vital role in science and international affairs by providing the essential framework for coordination and leadership of intergovernmental cooperation in understanding, observing, predicting, and ultimately protecting, the world’s oceans; and that it is doing so with remarkable efficiency and effectiveness given the magnitude of the task and the limited resources historically available to support its operation. The institutional arrangements for the IOC as an essentially autonomous agency within UNESCO are appropriate and helpful both to the pursuit of an integrated multidisciplinary approach to the oceans in collaboration with the other earth and environmental science programmes of UNESCO and to the development of effective partnerships with the many other international organizations, both inside and outside the UN system, with specific interests in, and responsibilities for, the oceans. There is no doubt that the benefits to individual nations and the entire global community from active involvement in the work of the IOC are immediate and substantial. It is also clear, however, that the pursuit of a more pro-active and strategic approach to understanding and management of the coasts and oceans is emerging as a global imperative for the twenty-first century. But it will require a rejuvenated IOC and a much greater investment than in the past. The Evaluation Team concludes that reaping the benefits of this investment by the global community will be heavily dependent on the extent to which UNESCO and IOC Member States recognise and grasp the opportunity to exploit the scientific and technological progress of recent decades and the synergies provided by the UNESCO commitment to science and international cooperation. This will require the revitalisation of the role of IOC within UNESCO and development of its unique potential for partnership with other UN and nongovernmental organizations in an integrated framework for marine research and operational oceanography for the twenty-first century. To this end, the Evaluation Team recommends: That UNESCO and its Members seize the opportunity to build on their initial investment (1) in the scientific study of the oceans in the second half of the twentieth century to provide the urgently needed global leadership in the development of operational oceanographic services for the benefit of all humanity through the twenty-first century. xii (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) That UNESCO sponsor and support the progressive development of the IOC as the UN specialised agency for the oceans, formally within the UNESCO framework, but working closely with the WMO and other partner agencies in the UN system. That the IOC governing bodies and Executive Secretary review and revitalise the IOC programme structures, planning, priority setting and management systems in line with its new statutes and based on modernised and streamlined arrangements for consultation and communication within the IOC Secretariat and Regional Offices. That UNESCO and IOC Member States be urged to strengthen their contribution to the work of the IOC through enhanced national marine programmes and increased financial and other support for the international planning and implementation of marine activities; and especially through extrabudgetary funding and the secondment of expert staff to participate in the international planning and management processes in both the IOC Secretariat and the Regional Offices. That IOC’s partner agencies and programmes within and outside the UN system be invited to join in the new and more integrated approach to exploiting the opportunities which recent developments in marine science and technology offer to the global community in the twenty-first century. That the more detailed findings and recommendations in the body of this Evaluation Report be referred for consideration and appropriate action by those concerned. 1 INTRODUCTION In November 1994, the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law ofthe Sea (UNCLOS) came into force and granted coastal States the right ofjurisdiction over ocean space and resources up to two hundred nautical miles from their shores, potentially even further over continental shelf seabed resources. For many countries, these new areas represented huge extensions of both opportunity and responsibility, and a large number of nations found themselves ill-equipped either to take advantage of the potential benefits or to adequately respond to the new management challenges. In addition, despite the massive transfer of international waters to national jurisdiction, over half the world surface remains a global ocean commons. In 1998, the world celebrated the International Year of the Ocean (IYO) and most nations and organs of the UN System focussed their attention, as never before, on humanity’s extraordinary and multifaceted dependence on the more than two-thirds of the earth’s surface that is covered by water. It also focussed attention on the remarkable fact that there is still no major international organization of Specialised Agency status, within or outside the UN System, responsible for intergovernmental cooperation and coordination of the collection and distribution of data, information and knowledge on the ocean. The world’s oceans represent a vital life support system for humanity in the twenty-first century. They are arguably the most bountiful yet the most threatened natural resource of the planet. Their vastness belies their fragility and the important and wide-ranging services they render to the global community contrast sharply with the limited extent to which they have yet been properly observed and understood. The oceans provide the physical linkage and the primary mode of transportation of natural resources and manufactured goods between maritime nations. Their evolution on timescales from days to millennia is a major determinant of the world’s weather and climate and they provide the key to better understanding of society’s vulnerability to natural disasters and the impacts of inadvertent human interference with the natural systems of the planet. More than half of the earth’s surface consists of international ocean demanding intergovernmental coordination of national programmes for its study and management. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO is uniquely placed to play this pivotal role. In particular, recent scientific and technological advances, outlined below, provide UNESCO with a window of opportunity to coordinate a new generation of services needed for the oceans, much as already exists for the atmosphere. The 1980s and 1990s have seen a revolution in global marine science and technology. It has brought the ability to provide daily global pictures of the dynamics of ocean surface physics, chemistry and biology from satellites. This capacity is coupled with new technologies for automated sensing at and below the ocean surface, feeding information into databases and ocean models in real time. The information technology and computing revolution pose exciting challenges for the IOC to coordinate international distribution and use of massive quantities of three-dimensional data for operational and research applications. These applications include forecasting El Nitio and other climate oscillations as well as waves, currents and storm surges, and managing fisheries. marine pollution, harmful plankton blooms, offshore oil and gas extraction ocean mining. shipping and coastal zone development. If these opportunities are to be grasped, and if society is to continue to draw on the vital sustenance and services provided by the oceans and maintain the habitability and quality of life on the planet. a vastly increased effort on monitoring, understanding, predicting and protecting the oceans must be recognised and embraced as a global imperative for the twenty-first century. 2 1.1 Purpose of this Report This Evaluation Report, which is directed initially to the Director General and governing bodies of UNESCO, takes stock of the role and achievements of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), as the primary international, intergovernmental mechanism in the UN system for dealing with the science ofthe ocean, in addressing the enormous opportunities and challenges opened up by humanity’s increasing awareness of the importance of the oceans. Its purpose is to provide UNESCO with an independent external evaluation of the capacities and capabilities of the IOC and a realistic course of action to ensure that UNESCO and the global community of nations reap the enormous benefits potentially available from investment in a new and rejuvenated IOC for the early decades of the new century. A list of the abbreviations and acronyms used in this report is provided in Appendix A. 1.2 The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) is a functionally autonomous and largely self-contained intergovernmental body that operates, in accordance with its own mandate and statutes, as a part of UNESCO and serves as the primary organization of the United Nations (UN) system for dealing with the science of the oceans. It was established by the Eleventh Session of the General Conference of UNESCO in 1960 in response to the widely-felt need, within the ocean science community at that time, for an intergovernmental mechanism for the international coordination of ocean science, much as was already provided by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), a separate Specialised Agency of the UN, for the atmosphere. It was recognised that a range of marine science responsibilities and activities already resided with other agencies and programmes of the UN system but that UNESCO, with its broad mandate and commitment to science, would provide the most appropriate sponsor and institutional home for the new organization. In order, however, to ensure effective cooperation between the IOC and all the other organizations of the UN system in the planning and implementation of an expanded programme of international cooperation in marine science, the participating agencies agreed, through the 1969 ICSPRO (Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography) Agreement, to recognise the IOC as an effective joint specialised mechanism through which to discharge certain of their own responsibilities in the field of marine science. This included, for example, the secondment of staff from other agencies into the secretariat that had been established within UNESCO to support the work of the IOC. Initially there was some overlap of responsibilities between UNESCO’s own work in marine science and the new Commission and some ambiguity in the framework of governance ofthe IOC which had been established with its own membership. open to all Members of UNESCO, and its own intergovernmental Assembly and Executive Council (initially Consultative Council). In 1987. however, the Twenty-fourth Session of the UNESCO General Conference conferred full functional autonomy on the IOC and, over the following decade, a series of IOC study groups reexamined the statutes, structure, operations and development of the Commission and prepared proposals for new statutes which were approved by the Twentieth Session of the IOC Assembly in July 1999 and subsequently by the Thirtieth Session of the General Conference of UNESCO in November 1999. A brief history of the development of the IOC from its establishment in 1960 until the recent approval of the new statutes is provided in Appendix B. 3 The new statutes, which provide the formal mandate and charter of the IOC, are at Attachment C. Under Article 1 of the statutes: . The Commission is established as a body with functional autonomy within UNESCO. . The Commission defines and implements its programme according to its stated purposes and functions and within the framework of the budget adopted by its Assembly and approved by the General Conference of UNESCO. Article 2 of the new statutes defines the basic mission of the IOC in the following terms: . The purpose of the Commission is to promote international cooperation and to coordinate programmes in research, services and capacity-building, in order to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas and to apply that knowledge for the improvement of management, sustainable development, the protection of the marine environment, and the decision-making processes of its Member States. . The Commission will collaborate with international organizations concerned with the work of the Commission, and specially with those organizations of the United Nations system, which are willing and prepared to contribute to the purpose and functions of the Commission and/or to seek advice and cooperation in the field of ocean and coastal area scientific research, related services and capacity-building. Membership of the IOC is open to any Member State of any one of the organizations of the United Nations System. It has grown from a membership of 40 in 196 1 to 127 in 1999. The supreme organ of the IOC is the Assembly which consists of all State Members of the Commission. It is convened in ordinary session every two years to, inter alia, establish general policy and the main lines of work of the Commission, approve its biennial Draft Programme and Budget, and elect its Chairperson and five (previously four) Vice-Chairpersons and its Executive Council which consists of up to 40 Member States, including those States represented by the six elected officers. The Executive Council meets annually to carry out the responsibilities assigned to it by the Assembly. The overall structure of the IOC, including its recently reorganised program structure, is shown in Appendix D. The scientific activities of the IOC constitute part of the UNESCO Major Programme II on “The Sciences in the Service of Development”. Along with: . Earth sciences, earth system management and natural disaster reduction (including the International Geological Correlation Programme (IGCP)); . Ecological sciences (including the Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB)); . Hydrology and water resources development (including the International Hydrological Programme (IHP)); and . Social transformation and development (including Management of Social Transformations Programme (MOST)); it makes up the UNESCO Programme on “Science, Environment and Socio-economic Development” with effective coordination mechanisms operating across the five programmes. However, only the IOC operates with the dual status of a UNESCO programme and an autonomous intergovernmental body. The IOC Secretariat consists of the Executive Secretary who is appointed, at the level of Assistant Director General (ADG), by the Director General of UNESCO, following consultation with the Executive Council of the Commission; along with “such other staff as may be necessary, provided by UNESCO, as well as such personnel as may be provided, at their expense, by other organizations, the United Nations system, and by Member States of the Commission”. 4 The current (January 2000) structure of the IOC Secretariat, including the details of permanently filled posts, consultant staff and secondees, is shown at Appendix E. In summary, the current staffing situation of the IOC Secretariat is as follows (where “UNESCO” refers to presently occupied permanent posts funded through the UNESCO Regular Budget and “OTHER” includes staff secondment by Members and other organisations, staff funded from extra budgetary sources through the IOC Trust Fund (and other Funds in Trust) and consultants/supernumerary staff funded through maintaining a small vacancy factor in the 22 UNESCO posts and through other sources). The details are shown separately for Professional (Prof.) and General (Gen.) staffas well as the totals: I UNESCO PROGRAMME/ACTIVITIES Prof. Ocean Science Operational Observing Systems Ocean Services Regional Activities Management and Coordination TOTAL Total Prof. Gen. ALL STAFF Total Prof. 9 7 2 2 3 3 5 5 7 5 0 1 7 6 1 1 2 1 4 3 2 6 2 4 1 0 0 1 2 4 2 21 19 2 21 2 I8 Gen. OTHER 113 27 Cm. Total 3 4 11 2 1 5 5 6 8 15 42 12 The total resources available for the operation of the IOC consist of: . resources provided from the UNESCO Regular Budget (including personnel costs associated with the UNESCO permanent posts (22) assigned to the IOC; Regular Budget programme funds; and resources provided in kind (accommodation, conference facilities, documentation services, etc)); . resources provided from other sources (including funds contributed by Members and collaborating organisations to the IOC Trust Fund; staff secondments and in-kind support to the IOC Secretariat; and the substantial resources committed by Members to the implementation of IOC programmes at the national level). That part of the total resources which can be readily identified in financial terms and which fall broadly under the authority of the Executive Secretary of the IOC, may be summarised for 1998 from the most recently published IOC Annual Report as (US $000 rounded): SOURCE OF FUNDS PERSONNEL COSTS PROGRAMME FUNDS TOTAL UNESCO Regular Budget IOC Trust Fund 1831 1380 766 1465 3211 223 1 TOTAL 2597 2845 5442 The recent resource history of the IOC (1990-91 to 1998-99 biennia) is summarised in Appendix F, along with the provisional budget for 2000-01. Although it is not possible to attribute historical expenditure uniquely acrossthe current IOC programme structure summarised in Appendix D, Appendix F indicates the allocation of the 2000-01 budget across a number of types and objects of expenditure in line with UNESCO 2000-01 Budget documentation. 5 1.3 The Evaluation This independent external evaluation of the IOC was commissioned by the Director General of UNESCO in 1998 as part of the UNESCO biennial evaluation plan for 1998-99. It resulted from the perceived need within the governing and subsidiary bodies of the IOC for systematic evaluation of the programmes and activities of the Commission and the desire of the governing bodies of UNESCO for better knowledge of the IOC. The general goal of the evaluation, as advised to the members of the Evaluation Team on 29 March 1999, was “to provide an objective review of the capacities and capabilities of the IOC as an intergovernmental organization and a dedicated UN mechanism whose mission is to lead, promote and coordinate the development of knowledge and observations of the ocean by its Member States, with the purpose of preserving the integrity of the life supporting system of the earth and of providing the suite of related environmental services”. It was agreed that the evaluation of IOC should: . provide an assessment of its current effectiveness and its capacities to respond to the changing conditions in which it operates; . provide an assessment of its administrative effectiveness and efficiency; . identify key lessons learned in programme implementation and assesstheir implication for future programming of the IOC’s activities. It was also agreed that the evaluation should lead to recommendations on: . future orientation of IOC’s activities, including their concentration and sharing their responsibilities between partners; . decentralisation and regionalisation of activities; . reorientation or termination of some programme activities; . management and accountability to the governing bodies of the IOC and UNESCO; . effective use of results, public awareness and information. The membership of the Evaluation Team (Appendix G) was approved by the Director General in March 1999 following consideration of a list of nominations by UNESCO National Commissions. Its final composition was: . Dr John G Field, Professor, Zoology Department, University of Cape Town, South Africa and President of the ICSU (International Council for Science) Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR), Cape Town, South Africa; . Dr Elie Jarmache, Director of International Relations, Institut Francais de Recherche pour 1’Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER), Paris, France; . Dr John W Zillman, Professor in the School of Earth Sciences of the University of Melbourne, Chairman of the Australian Commonwealth Heads of Marine Agencies (HOMA), Director of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and President of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Melbourne, Australia (Team Leader). Secretariat support to the Evaluation was provided by Dr Iouri Oliounine, Deputy Executive Secretary of the IOC. The Evaluation Team first met at IOC headquarters in Paris on 22-23 June 1999 for a general briefing on the UNESCO evaluation methodology and an exchange of views on the scope and conduct of the Evaluation. The Team was supplied with a substantial amount of documentation including the UNESCO Biennial Programme and Budget, statements made by Member States at the 1997 UNESCO General Conference, technical documents on the IOC Programme, current 6 budgetary documents prepared for discussion at the IOC Assembly, the then current IOC statutes and rules of procedure, the IOC Annual Report for 1998 and a variety of project-related documents and reports. The members of the Team also had the opportunity to participate in meetings of the Twentieth Session of the IOC Assembly held in Paris from 29 June -9 July 1999. A principal outcome of this initial meeting was formal agreement on the final terms of reference for the Evaluation as being to: provide an objective and detailed review of the capacities and capabilities of IOC in (9 carrying out its mission; provide an assessmentof the current effectiveness of IOC programmes and IOC capacities (ii) to respond to changing needs and circumstances; provide an assessment of the IOC administrative effectiveness and efficiency; (iii) provide recommendations for the IOC future activities and related administration. (iv) The Team agreed to follow the general methodology for evaluation of UNESCO programmes as set out in the 1994 Reference Manual “Evaluation of Programme Activities at UNESCO” and as elaborated, in the IOC context, by the Assistant Director General-IOC, Professor Patricia Bernal, and the Director of the UNESCO Central Programme Evaluation Unit, Dr Michail Reshov. The principle means adopted by the Team for assembly of the information base for its Evaluation, in addition to all the relevant current and historical IOC documentation, included: . preparation of a questionnaire (Appendix H) to IOC Member States (distributed on 3 August with a requested return date of 15 September 1999) seeking information and views on: the relative importance of various marine activities, - the effectiveness of the IOC, - the efficiency of the IOC, - the value of the IOC to individual countries, - national participation in IOC programmes, national arrangements for participation in the IOC, future development of the IOC; . consultation with IOC officers and delegates attending the Twentieth Session of the IOC Assembly 29 June-9 July 1999; . written invitations to some 24 international organizations represented at the Twentieth Assembly to provide views on any aspect of the operation of the IOC relative to the terms of reference of the Evaluation; . the commissioning of two consultants to the Evaluation Team: the immediate past Chairman of the IOC, Mr Geoffrey L Holland (2WE Associates Consulting Ltd), who canvassed widely in the international marine science community (including longstanding delegates to the IOC, representatives of other UN specialised agencies, Chairs of IOC technical committees and regional bodies, chairs of scientific committees and senior staff) for issue identification and views for consideration by the Team; and who generally assisted the Team with information and advice, Mr Martin Brown, a former OECD economist, who carried out a survey of studies of the economic value of IOC and other marine science programmes; . a detailed review of the WESTPAC (Western Pacific Sub-Commission) Office of IOC in Bangkok, Thailand on 2-4 December 1999 by a subgroup of the Evaluation Team consisting of Professor Field (Leader) and Professor Zillman; 7 . . a Team meeting with all available IOC staff in IOC headquarters on 8 December 1999 and later meetings with senior IOC programme managers and individual staff members who wished to meet privately with the Team; consultation (in Paris on 8-9 December 1999) with various senior staff of UNESCO responsible for a range of scientific programmes with significant linkages to the IOC including: Dr Gisbert Glaser. Assistant Director General for Coordination of Environmental Programmes (ADGCORENV), Dr Mauritzio Iaccarino? Assistant Director General for Natural Sciences (ADGSC), Dr Peter Bridgewater, Director of the Division of Ecological Sciences (DIR/SC/EGO), Dr L Mandalia, Programme Specialist in the Division of Water Sciences. The Team met finally in Paris on 7-10 December (for part of the time with the assistance of the IOC Secretariat and consultants and for part ofthe time in closed session) to agree on its principal findings, conclusions and recommendations and prepare its draft report. Following consideration of further input from those consulted until mid-February 2000, the Team adjusted its conclusions and recommendations and finalised its report by correspondence. The remainder of this final report of the Evaluation is structured as follows: Section 2 addresses Term of Reference (i) of the Evaluation (“provide an ob.jective and detailed review ofthe capabilities of IOC in carrying out its mission”) by summarising the Team’s assessment of the overall mandate, structure and operation of the IOC as an intergovernmental organization; Section 3 addresses Term of Reference (ii) of the Evaluation (“provide an assessment of the current effectiveness of IOC programmes and IOC capacities to respond to changing needs and circumstances”) by reviewing the structure and performance of the scientific and technical programmes of the IOC, along with the planning, management and resourcing of the work of the Commission. Section 4 addressesTerm of Reference (iii) of the Evaluation (“provide an assessment of the IOC administrative effectiveness and efficiency”) by examining the organization and operation of the IOC Secretariat and the overall allocation and management of the financial and staff resources of the Commission; Section 5 addressesTerm of Reference (iv) of the evaluation (“provide recommendations for the IOC future activities and related administration”) by drawing together the findings, conclusions and recommendations of Sections l-4 and presenting the overall lessons learned from the Evaluation and from the work of the IOC for consideration by the Director General and the governing bodies of UNESCO and the IOC. Conclusion and Recommendation On the basis of the substantial body of information and expert opinion assembled for the purposes of its evaluation of the IOC, the Evaluation Team reached one overarching conclusion on the importance of the oceans to humanity in the twenty-tirst century and wishes, at the outset, t,o convey to the Executive Director and governing bodies of UNESCO its strongest recommendation that UNESCO seize the unique opportunity now available to ensure that the benefits of its investment in ocean science in the second half of the twentieth century are realised for the good of all humanity in the twenty-first century. Thus. the Evaluation Team concludes and formally recommends as follows: 8 Conclusion 1 - The oceans represent a unique but seriously threatened global commons whose scientifically based monitoring, understanding, prediction and protection will be vitally important to community welfare and planetary survival in the twenty-first century. Recommendation 1 - That UNESCO and its Member States seize the opportunity to build on their initial investment in the scientific study of the oceans in the second half of the twentieth century to provide the urgently needed global leadership in the development of operational oceanographic services for the benefit of all humanity through the twenty-first century. 2 IOC STRUCTURE AND OPERATIONS The difficulties and costs of observing and describing ocean processes are immense and far beyond the capabilities of any single nation. When the IOC was established forty years ago, scientific awareness of the global interdependence of ocean processes and their vital links to, and influence on, the atmosphere were only just beginning to be understood. UNESCO’s decision in 1960 to establish the IOC to begin to develop, for the ocean. the international framework of cooperation and data exchange that had already been in place for the atmosphere for almost a century under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and its predecessors was a bold and farsighted initiative. So was its decision to support the concept of the IOC as a joint specialised mechanism of the UN system for the oceans under the ICSPRO Agreement and subsequently to grant it functional autonomy within UNESCO. The Evaluation Team was conscious of the extent to which any assessment of the overall performance of the IOC (“provide an objective and detailed review of the capacities and capabilities of the IOC in carrying out its mission”) must take account of the history of its development. 2.1 The Evolution of the IOC as an International Agency It is useful to review the various influences on the development of the IOC over the period 196099 as a basis for understanding its present strengths and weaknesses and its capacity to serve as the foundation for the greatly increased focus on the oceans which is emerging as a global imperative for the decades ahead. As the membership of the IOC grew through the 1960s and 70s the composition of Member States and the direction of its programme evolved. Whereas initially, the membership was largely composed of countries with an established capability in marine science, many of the newer Members were less fortunate. The original focus on marine science was thus broadened to encompass capacity building and technology transfer. The changes taking place in the legal regimes governing the oceans were passing more responsibilities onto Coastal States in terms of the management of areas out to 200 nautical miles or more offshore. Resolving the needs of science with the expanded national jurisdictions over marine resources brought political arguments to the tables of the IOC governing body meetings. The expanded membership of the Commission and the increased awareness of ocean issues led to a rapid increase in programme activities that was not matched by a concurrent increase in staff and resources. For the first decade or so: the IOC had operated within the UNESCO system, with little attention asked for. or offered, by its parent organization. This came to an end with the arrival of the economic constraints of the eighties and nineties. The programmes adopted at the IOC Assembly were necessarily curtailed by the competition for funds amongst other programme demands at the General Conference. The “functional autonomy” enjoyed by the IOC in the 9 selection of its programmes became more and more constrained by the inability of UNESCO to supply adequate funding. Some additional contributions were solicited from Member States in the form of targeted funds deposited to an independent Trust Fund account. This was only a partial solution and. as the economic situation worsened, so did the competition for funds at the UNESCO General Conference. With its continual demands for additional support, the IOC found itself increasingly unwelcome in the tightly constrained budget decision-making fora of the General Conference. Although UNESCO lost two of its major funding sources with the withdrawal ofthe LJSand UK as Member States in 1983. both countries were able to continue as Member States of the IOC and indeed transferred funding directly to the IOC using Trust Fund arrangements. One unfortunate result of this development was to cast the IOC as a “privileged programme” of UNESCO, bringing its autonomous status under scrutiny and subjecting its applications for additional support from the Regular Budget to a high prospect of rejection. The IOC was initially supported by several related UN agencies through the interagency ICSPRO Agreement and secondment of staff. Unfortunately, however, the tightening funds situation in the ICSPRO agencies resulted in the progressive withdrawal of all but the staff member from WMO. The ICSPRO still exists and, in general, cooperation amongst the agencies continues. especially with the WMO. Cooperation with WMO has always been strong and productive and has been reemphasized, amongst other developments: by joint IOC-WMO sponsorship of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) and, most recently, through the establishment of their Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM). Through the 1980s and early 90s new priorities arrived for programmes to address the immediate concerns of both developed and developing countries in coastal and ocean resource management and these competed for attention with the emergence of global environmental issues such as ocean health, climate change and biodiversity. The IOC statutes were rewritten to encompass service and management programmes that could be justified more directly on a cost-benefit rationale. The IOC statutes recognize that the Commission’s programmes will be implemented through the collective efforts of Member States and developed through its regional bodies. Many Member States extended their support directly to the Secretariat through secondments of personnel that alleviated staff shortages in Paris, but the lack of support available to the Regional Offices emerged as a critical problem. The obvious benefits of operating under the auspices of UNESCO have, to a significant extent, been undermined by the perceived lack of status for the Commission. The efficiencies of scale which should have resulted from using the financial and management staff of UNESCO have also been negated to a significant extent by the unavoidable duplication of management procedures within the IOC and UNESCO leading to delays and confusion. What should have been a positive partnership has, at times, deteriorated into a situation of conflict and frustration. Up to 1998, the functional autonomy of the IOC was implemented by means of the delegation of authority from the Director-General ofUNESC0 to the Executive Secretary of the IOC. During the Nineteenth Assembly, in July 1997, the Director-General announced the upgrading ofthe Post of Executive Secretary of IOC to the level of Assistant Director-General (ADG). The special authorizations achieved through the delegation of powers to the Executive Secretary of IOC have thus been superceded since they now fall within the regular authority of any ADG of UNESCO. Furthermore, this new status is not linked to the incumbent but to the post of Executive Secretary 10 and is now reflected in the IOC statutes. The ADG/IOC now has specific written instructions as to his duty of reporting directly to the Director General and for co-ordinating programme execution with the ADG/SC (Assistant Director General for Natural Sciences) and the ADG/COR/ENV (Assistant Director General for Coordination of Environmental Programmes). All administrative procedures of the IOC continue to be served by the same administrative unit as the Science Sector that, according to UNESCO regulations and standard practice in such organizations, do not report to either of the two ADG’s, but to the ADG for Administration (ADG/ADM). The Commission has benefited from the creation of the IOC Special Account under Article 6 of UNESCO Financial Regulations. Although this mechanism is shared by many UNESCO bodies outside headquarters. it is restricted to very few within headquarters. The application of the decision of the Twenty-eighth General Conference to provide a protected or incompressible budget for the IOC has allowed for improved financial planning for the IOC activities and has also been a major incentive for Member States to contribute to the Special Trust Fund Account for IOC (a total of US$l.978 million from twelve Members in 1998 according to the IOC Annual Report for 1998). 2.2 Role and Statutes The Evaluation Team was aware of the extensive process of study and consultation undertaken under the auspices of: . the IOC ad hoc Study Group on Measures to Ensure Adequate and Dependable Resources for the Commission’s Programme of Work (FURES), whose last report was considered by the IOC Assembly at its Sixteenth Session (1991); . the IOC ad hoc Study Group on Development, Operations, Structure and Statutes (DOSS), whose final report was considered by the IOC Assembly at its Twentieth Session (1999); and concluded that the role envisaged by the IOC governing bodies for the Commission in the early years of the twenty-first century is essential and important and is appropriately reflected in the new statutes (Appendix C) as approved by the Thirtieth Session of the General Conference of UNESCO in November 1999. While these new statutes may need further amendment in a few years’ time to reflect the enhanced role, status and influence for the Commission which would result from UNESCO acceptance of the Recommendations of this Report, the Evaluation Team believes they provide an appropriate legal and organizational framework for the operation of the IOC for the immediate future. 2.3 Governance The mechanisms for governance ofthe IOC reside in the operation of its Assembly and Executive Council with the composition and functions set down in the statutes (Appendix C). Probably more so than most other UN system bodies, the IOC governing bodies reflect both the stimulus and the tensions associated with the juxtaposition of the separate cultures of science and international relations but the combination has generally worked well over the years despite the inevitable problems of communication and occasional frustration on both sides. The generally informal working style of the plenary meetings of the Assembly and Executive Council based on a high level of professional camaraderie between most of the participants, has 11 proved conducive to effective cooperation and the prompt resolution of what, in more politically charged fora, frequently turn into difficult impasses. Although the IOC tradition, based on UNESCO’s own practices, of working through a formally registered list of speakers rather than opening up the floor to the cut and thrust of debate, may tend to suppress some spontaneity, it provides a useful discipline on the formal business and is well complemented by other less formal mechanisms for Member input such as the facility for submission of draft resolutions. The Evaluation Team found a moderate to high level of satisfaction with the efficiency of operation of the Assembly and Executive Council amongst national delegates, albeit with the inevitable frustrations on the part of some individuals, particularly those with strong scientific interest in particular issues and little time available to commit to the general debate on issues and programmes outside their area of special interest. While most experienced participants in Assembly and Executive Council sessions welcome the involvement of UNESCO Permanent Delegation representatives in the debates as a mechanism for raising the awareness of IOC programmes in UNESCO and in broader diplomatic circles, the intrusion of politically based arguments into the debate can lead to some alienation of the more scientifically inclined and professionally committed delegates and some criticism of the workings of the IOC from within the broader scientific community. Some delegates and external observers believe the IOC governing bodies could make increased use of the Vice-Chairpersons during their sessions in addition to the particular portfolios of responsibilities that they may accept in the overall working of the IOC. The IOC’s Regional Sub-Commissions and Regional Committees are viewed somewhat ambiguously by Members. In general they are neither as satisfactorily institutionalised or effectively focussed as their counterparts in some other organizations and might benefit from adoption/adaptation of some of the working methods and discipline of mechanisms such as the Regional Associations of the WMO. The IOC has had a need for special groups and programme activities that deal with policy and political issues rather than scientific and technical problems. In fact, over the past two decades there has been a virtual standing committee, albeit changing its name from time to time ( FURES, FUROF, DOSS-l and DOSS-2), that has looked, inter alia, at the statutes, rules of procedure, funding requirements, geographical representation and subsidiary bodies. In many respects, it has been a useful process, allowing the governing bodies to avoid becoming bogged down in difficult issues by passing them on to these special groups. The danger is always present, however, that the presence of such bodies encourages delays in decision-making. In the earlier days, the composition of the group was largely dictated by the IOC Chairman working in consultation with the Executive Secretary and his Vice-Chairmen. The last group, however, the DOSS-2 Group, was open-ended. The most recent Assembly did not establish a further group. Other groups have been established by decision of the Assembly or Executive Council to deal with such matters as the involvement of the IOC in UNCLOS, consultations on the development of programmes, programme evaluation or advisory groups. Overall, the Evaluation Team found that the IOC governance mechanisms and their operation are regarded as broadly satisfactory, albeit with some scope for improvement through adoption/adaption of organizational or procedural arrangements found useful in other organizations. 12 2.4 National Representation Member States send delegates to the governing body sessions of the IOC to represent their views and interests in discussions on the direction of policies and programmes of the Commission. Such national representation usually reflects the individual governmental structure, with regard to ocean management, within each respective Member State. For some countries, the prime ocean interests reside in the military, for some it is within the research community, for some it is linked to fisheries management and for others to environmental matters or to the responsibilities of the National Meteorological Service. This variety of interests, although demonstrating the wide influence of marine science and services, tends to lead to a lack of cohesion when addressing ocean matters at the intergovernmental level. The representation at the IOC therefore contrasts with most other UN agencies, such as the WMO, where the Permanent Representatives and Principal Delegates to sessions of the governing bodies are usually the Directors of the National Meteorological Services of the Member States and agreed actions can be consistently and promptly implemented within established national structures. A further complication with national representation in the IOC is that of coordination between the national representation at the IOC governing bodies and at those of UNESCO. The situation often develops where the national priorities put forward by a delegation to the IOC are not endorsed by the delegation of the same country to UNESCO. This is not the fault of the Commission but the product of lack of adequate communication within national governments. This lack of cohesion and communication is a pervasive problem caused by the segregation of issues within governmental departments and amongst UN agencies. It has emerged as a practical problem in recent times because many present day issues can only be addressed by multidisciplinary approaches and through cooperative action. It is certainly not a problem that arises only in the IOC, but the very nature of the oceans creates a special need for common approaches and collective solutions. The Evaluation Team found widespread support for proposals for renewed efforts to persuade Member States to set up national committees to rationalize their approach to intergovernmental ocean matters. Such committees should be an integral part of the overall framework for coordination of national participation in the programmes of UNESCO to improve the coordination of IOC Assembly and UNESCO General Conference decisions. Allowance must, however, be made for the fact that IOC’s programmes impinge upon a range of potential users that usually extend beyond the traditional UNESCO constituencies represented in most Member States by the Education and/or Science Ministries. 2.5 Cooperation with Other Organizations Cooperation and partnerships are absolutely essential to the work of the IOC. They are an effective way to avoid overlap and to increase the capacity of the Organization. The administration of such partnerships, however, places heavy demands upon the IOC Secretariat. If partnerships are ignored or poorly serviced due to lack of attention, they languish and become a drain on resources rather than a benefit. The IOC has a reasonable record in the area of cooperation with other agencies. In the words of an IWCO (Independent World Commission on the Oceans) study on international ocean organizations “The IOC has co-operated with all relevant organizations in these and other efforts. It is in reality surprising that IOC has been able to do all it has done.” On the other hand, the present Evaluation Team received some criticism of a perceived duplication of effort with and between outside agencies, especially in the regions. 13 The IOC has advisory bodies, joint bilateral and multilateral coordinating bodies, memoranda of understanding, inter-secretariat bodies, interagency arrangements and co-operative programmes. In its evaluation of the IOC’s performance in cooperation with other agencies, the Evaluation Team focussed its attention on the major partnerships. The major scientific advisory body to the IOC has been the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR). This independent organization of ICSU (International Council for Science) has provided general advice ad co-operated with the IOC on specific programmes. The roles of IOC and SCOR are complementary. SCOR consists of active marine scientists and deals with scientific issues, but lacks the political influence of a UN agency. SCOR is also able to advise on suitable scientists to serve on various committees because of its close links into the marine science community. At present, it is cooperating with the IOC in the preparation of a major publication on Ocean Science to the year 2020. The IOC partnership with SCOR is widely recognised as having been extremely valuable and productive, especially during the last decade. One of the most important external interactions for the IOC is with the United Nations (UN) itself and, in particular, with its Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into force on 16 November 1994, provides, in its Part XIII, the legal regime for the conduct of marine scientific research by States and international organizations (Article 247). States as well as competent international organizations have an obligation to promote international cooperation in marine scientific research for peaceful purposes and to publish and disseminate relevant information and knowledge. The regime envisaged by UNCLOS needs concrete policies and results-oriented initiatives to be formulated and implemented. It is clear that, as the competent international organization, IOC should play an increasingly assertive role in marine scientific research in particular in view of its amended statutes which provide that its purpose is to “promote international cooperation and to coordinate programmes in research ... in order to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas ...” There is scope for much more proactive cooperation between the IOC and the UN Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea over the next few years. The strongest ties with another UN Specialized Agency have been with the WMO, starting from the Joint IOC/WMO Working Committee for IGOSS and leading to the recently established Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM), an innovative and far-reaching partnership which will increasingly seethe IOC and WMO working through a single mechanism for international coordination in marine meteorological and oceanographic monitoring and service provision. The IOC has maintained close and productive ties with the WMO since its establishment. In addition, the two agencies have cooperated closely as co-sponsors of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), the Data Buoy Cooperation Panel (DBCP) and the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS). Officers of the IOC and WMO regularly attend governing body and other relevant programme meetings of the other organization. The close partnership also leads to collaboration on training, conferences and other ocean-related activities. It is generally felt that cooperation between these two agencies has strengthened significantly over the years to mutual benefit. The flow-on to improved coordination and cooperation between the oceanographic and meteorological communities at the national level has also been warmly welcomed in most countries. Whereas cooperation with the WMO has progressed well, the co-operation with UNEP has so far been disappointing, except in a few specific areas. In particular, the Regional Seas programme of UNEP should be a fertile area for IOC participation. The scientific and technical expertise from the IOC and its regional bodies could provide much needed support to the regional agreements, 14 whilst the exposure of the IOC to these political arrangements would enhance the status of, and support for, the IOC in the regions. The IOC was not heavily involved in the Washington Agreement on the Prevention of Marine Pollution from Land-Based Sources, conducted largely under the auspices of UNEP albeit in an area of IOC expertise. UNEP and the IOC are joint sponsors of GIPME (Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment) and cooperate under ICSPRO and GESAMP (Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environment Protection). There appears to be scope for considerable strengthening of cooperation between the IOC and UNEP over the next few years. ICSPRO, the Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Related to Oceanography, is a long standing cooperative arrangement that has languished in recent years. Originally set up to encourage co-operation amongst the UN Specialized Agencies dealing with the Oceans (IOC, UNESCO, UNEP, WMO, IMO, FAO, ...). i t initially worked well in ensuring effective cooperation within the UN System and staff from the other agencies were seconded to the IOC to promote cooperation. Unfortunately, as indicated earlier, only the WMO staff secondment has survived. There would be value in a reassessment of the need, purpose, and effectiveness, of the ICSPRO arrangement. A second and currently more powerful inter-secretariat committee is the ACC (Administrative Committee on Coordination) Sub-Committee on Oceans and Coastal Areas (ACC-SOCA). This mechanism is charged with the function of Task Manager for Chapter 17 of Agenda 2 1. As such, it has to report to the UN Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) on the follow-up activities. The last two reports to the UNCSD have been seen as disappointing by many in the ocean community, being more ofthe nature of a factual list of activities in the respective agencies without much attention to reviewing performance or addressing policy issues. The IOC is currently providing the chair (IOC Executive Secretary) as well as the ongoing secretariat to this subcommittee. Although this is a visible and responsible role for the IOC, it also carries a heavy workload and the benefits to the IOC are not immediately evident. It remains to be seen whether this new role for the IOC can impact on UN ocean policies and enhance the effectiveness of IOC in the broader international fora. It will be important, in a few years, to evaluate the new arrangement with the IOC-WMO JCOMM, which has placed inter-agency cooperation at a higher level than hitherto. Similar arrangements might be contemplated with the FAO, IMO and UNEP and might also serve as a model for UNESCO-WMO cooperation in other areas such as hydrology and natural disaster reduction. The IOC has signed Memoranda of Understanding with several non-UN bodies including the IHO (International Hydrographic Organization), ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea), the International Union of Geographers and ACOPS (Advisory Committee on Protection of the Sea). One difficulty is maintaining the impetus for such arrangements when the initial programmes have terminated or the original rationale has changed. MOUs should be designed to provide a general co-operative agreement stating the general expectations and support from each organization to mutual benefit. They should allow for the addition and termination of discrete programmes that can be annexed to the MOU without the need for renegotiation of the basic cooperative agreement. Each new suggested programme would be accepted or rejected on its individual merits. Of course the MOU itself should be reviewed and altered if necessary on a longer time frame or when both organizations agreed changes were necessary. The IOC co-sponsors joint groups of experts such as the GESAMP and the Guiding Committee for GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans). The benefit of such arrangements has 15 been very apparent over the years with the results complementing the IOC programmes. The Evaluation Team found strong support for the IOC continuing with such cooperation as appropriate. Finally. one of the closest partnerships for the IOC is that with the other science activities of UNESCO. Over the last four years, the other science programmes of UNESCO and the IOC have cooperated in a multidisciplinary and issue-oriented manner. The Evaluation Team found strong support for this development. As indicated above, the science programmes of UNESCO include geology, hydrology, ecology and the social sciences. The Chairperson of the IOC and the Chairs of the other science programmes now meet. at the time of the UNESCO General Conference, to develop a joint statement to UNESCO. The statement provides an opportunity for the programmes to make a collective review of science within UNESCO and to suggest actions. A further useful step would involve the development of a mechanism for joint collaboration with the related programmes of other science agencies external to UNESCO, such as the WMO. 2.6 Planning and Evaluation The Evaluation Team reviewed the IOC planning and evaluation mechanisms both within the context of the larger UNESCO framework and with a specific focus on marine science. While there was evidence of excellent strategic thinking and effective programme planning and management in some subsidiary bodies of the IOC, in general the Team found that the Commission lacks an effective organization-wide strategic planning, management and evaluation framework. There was a widespread view that, despite the additional workload involved for Members, the governing bodies, subsidiary bodies and the Secretariat, a more systematic approach to planning and evaluation is a necessary discipline and a prerequisite for substantially increased support by Members and from the governing bodies of UNESCO. 2.7 Conclusions and Recommendations Based on its general impressions and findings, summarised above, on the appropriateness of the new statutes of the IOC to current national and international needs, and its assessmentof the role and operation of the Commission, the Evaluation Team concludes and recommends as follows: Conclusion 2. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) has responded effectively to the changing national and international needs for coordination and cooperation in oceanography and its current statutes and its governance and working methods are appropriate to the contemporary international situation in marine science. Improvement is needed in a number of areas including the arrangements for national representation, regional coordination arrangements and cooperation with other international organizations. The opportunity exists for the IOC to assume a proactive leadership role in international marine affairs in the twenty-first century. . C2.1. The IOC possessesthe experience, structure, linkages and scientific competence to contribute more strongly to the total science effort of UNESCO and to the broader UN system. . C2.2 The ICSPRO (Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography) Agreement is no longer working effectively and is in urgent need of reactivation or replacement by something more suited to contemporary needs. . C2.3 The new IOC statutes provide an appropriate legal and organizational framework for the future development of the Commission but they need to be supported by appropriate rules of procedure and agreed administrative structures and practices. 16 C2.4 . . . . . . The concept of operation of the Executive Council has proven to be effective and appropriate to the IOC role but it is important, when electing Member States to Council membership, to ensure that the Council retains a high level of specialist oceanographic expertise. C2.5 While the IOC is widely recognised for its scientific expertise, there has been a significant tendency in the past for its input not to be sought in the negotiation and implementation of international conventions and agreements which require substantial marine expertise. C2.6 The regional substructure of the Commission is poorly defined and largely ineffective with particular problems associated with its ability to provide a working framework for addressing agreed regional marine priorities. C2.7 Many Member States do not have effective national coordination mechanisms and, in general, the linkages between National IOC Committees (where they exist) and National Commissions for UNESCO are weak or non-existent. C2.8 The IOC has an excellent opportunity through its chairing and secretariat responsibilities for the new UN ACC-SOCA (United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination - Subcommittee on Oceans and Coastal Areas) to play a much stronger role in the UN handling of marine affairs. C2.9 There is substantial scope to build on the IOC-WMO (World Meteorological Organization) JCOMM (Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology) model to enhance IOC collaboration with several other marine-oriented agencies and programmes in the UN system. C2.10 The IOC lacks an adequate framework and system for strategic planning and programme evaluation. Recommendation 2. That UNESCO sponsor and support the progressive development ofthe IOC as the UN specialised agency for the oceans. formally within the UNESCO framework, but working increasingly closely with the WMO and other partner agencies in the UN system. R2.1 R2.2 R2.3 R2.4 R2.5 R2.6 R2.7 That the UNESCO Director General, Executive Board and General Conference endorse a new and more proactive leadership role for the IOC in international marine science and services based on a substantially strengthened commitment to the role of the Commission as a central element of the science mission of UNESCO. That UNESCO and the IOC, in partnership with the other ICSPRO (Intersecretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography) agencies, review the appropriateness of the ICSPRO mechanism with a view to its rejuvenation or replacement by some new mechanism more suited to contemporary needs. That new IOC rules of procedure be developed as a matter of urgency to facilitate and support the operation of the new statutes. That Member States nominating for membership of the IOC Executive Council be encouraged to identify individuals with strong personal marine science credentials as their representatives on the Council. That the IOC play a more effective role in global and regional marine conventions and agreements that impose obligations on Member States. That the IOC governing bodies undertake a comprehensive review of the regional structure of the Commission with a view to its rationalisation and sharper focussing on regional needs and priorities. That Member States, who have not done so, be urged to establish formal national oceanographic committees (National Committees for the IOC) as focal points for 17 IOC within their countries; and that these be established in close collaboration with National Commissions for UNESCO so as to ensure effective linkages between the National Commissions and all those institutions and agencies with an interest in the marine environment. R2.8 That the present IOC role as Chair and Secretariat of the UN ACC-SOCA (United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination - Subcommittee on Oceans and Coastal Areas) be given high priority and that the IOC communities within Member States be encouraged to develop complementary linkages into the UNCSD (UN Commission for Sustainable Development) process. R2.9 That the Executive Secretary investigate the scope for stronger and more effective ties with IMO (International Maritime Organization), UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) and the FA0 (Food and Agriculture Organization), based on the IOC-WMO (World Meteorological Organization) JCOMM (Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology) model, with a view to improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the IOC role. R2.10 That the IOC governing bodies and Executive Secretary give priority to the development and implementation of an appropriate system of strategic planning and programme evaluation compatible with the needs and working methods ofthe Commission. THE IOC PROGRAMME The Evaluation Team attached particular importance to that part of its task (“provide an assessment of the current effectiveness of IOC programmes and IOC capacities to respond to changing needs and circumstances”) related to IOC’s performance of its central role in international marine science in the belief that its findings on this aspect would be of special interest to UNESCO and IOC Members and to the Executive Board and General Conference of UNESCO in the context of the overall scientific programme of UNESCO. Unfortunately, while there is much evidence to suggest that many IOC programmes are well managed and effective and are highly valued by Members, the Evaluation Team had a great deal of difficulty in obtaining firm information on programme structure, plans, budgets, performance information and the like. This is a serious shortcoming in the current operation of the IOC, given the now almost universally expected disciplines of programme planning, management and performance evaluation in national governments and the UN system generally. The general discussion and findings which follow and which form the basis for the Team’s conclusions and recommendations are based mainly on informal exchange of opinion, anecdotal evidence, questionnaire responses and briefings by Secretariat staff. Some general observations and impressions are followed by separate consideration of the major programmes of the IOC as identified in Appendix D. 3.1 Overall Impressions During the past decade, there has been a gradual shift from the traditional working structure of the IOC. which consisted of a range of programmes in science, services and TEMA (Training, Education and Mutual Assistance). each coordinated by an intergovernmental committee or panel of experts. In the present (and still evolving) structure, the IOC programmes are categorized, under three main headings, as Ocean Science, Operational Observing Systems and Ocean Services. In addition. there are cross-cutting programmes on Capacity Building (TEMA), 18 Regional Bodies, Partnerships, Joint Bodies with other UN Agencies and ad hoc programmes on special issues. The Evaluation Team found considerable frustration, amongst stakeholders, that past attempts to establish clear priorities for the IOC have not been successful. The reason is that massive effort is needed to resolve the many ocean problems, with all their intrinsic variety and complexity. It is extremely difficult to achieve consensus on priorities when the urgent needs of individual Member States cover the entire spectrum of ocean issues. It appears that any permanent solution to this dilemma must be based on a resolution of the issue of resources versus mandate. At present, the two are incompatible. In the current climate of zero or negative real growth which prevails in the UN system, a reduction in the size and scope of the 1,OCProgramme may, at times, appear inevitable, but resolution of priorities has been debated in the governing bodies of the IOC for years. without any satisfactory answers being found. Aside from the resource and mandate problems, which can only be resolved over a long time frame, there are many shorter term issues of efficiency, direction and programme management which must be considered. The Evaluation Team found that there was a widely held opinion that the overall IOC Programme is well implemented, in the circumstances, although some streamlining of its management machinery is felt to be necessary in order to reduce the number of committees, working groups, panels, etc within the IOC, and to reduce overlap of functions and duplication ofwork. The Team was impressed by the effort being undertaken by the Executive Secretary and his managers in this regard. As could be expected, there were many expressions of satisfaction with the IOC efforts but also some criticism of direction and performance, the least critical comments emanating from those countries with the most to gain from the international ocean science and service community. The Team recognized the often differing perspectives of developed and developing countries, the former being more inclined to support programmes aimed at confronting the challenges of the future while the latter assigned highest priority to dealing with the compelling problems of today. 3.2 Ocean Science The IOC Ocean Science Programme covers ocean sciences related to climate, living and nonliving marine resources, coastal zone management and pollution. All are linked closely to real problems and issues. The climate programmes include the IOC involvement with the Climate Variability and Predictability (CLIVAR) programme, the Ocean Observations Panel for Climate (OOPC) and the Global Ocean Data Assimilation Experiment (GODAE). All of these relate to the observational need for ocean and climate data and to the operational need for forecasting and prediction services. All are essential to the better understanding of climate and, if their intergovernmental oceanographic elements were not undertaken within the IOC, they would have to be assumed by some other international organization. Understandably, the climate programmes are carried out in partnership with the WMO and ICSU under the auspices of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), of which WMO, IOC and ICSU are the three sponsors. There is a financial burden for IOC involved with its cosponsorship of the WCRP, but the Member States have recognized the need to support the 19 programme and to contribute a strong ocean research direction. Governments and their constituencies are becoming more aware of the potential benefits and urgency of better understanding climate variability and long-term change, particularly as a result of the successful prediction of recent El Nifio events but also because of the perceived increased frequency of disastrous weather related events over recent years. The oceans play a key role in the earth’s climate system and the WCRP depends fundamentally on effective coordination with, and contributions from, the oceanographic community. There is no doubt that the IOC has responded well to the increased international emphasis on climate over the past two decades. The major TOGA (Tropical Ocean Global Atmosphere) and WOCE (World Ocean Circulation Experiment) experiments under the WCRP and JGOFS (Joint Global Ocean Flux Study) under the auspices of the IGBP (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme) are largely completed, with the IOC having played a vital intergovernmental supporting role. As knowledge is acquired on weather and climate prediction, it should automatically be folded into the forecasting and prediction networks and models. The IOC clearly has an important role to play in this process in collaboration with the WMO. The Evaluation Team is aware that the IOC needs also to be involved in longer-term more strategic research in ocean climate related to human-induced climate change. Within the overall OSLR (Ocean Science in Relation to Living Marine Resources) Programme, there are several programmes that are successful and of high priority and which attract strong support from Member States. The Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) programme, for example, has received accolades from many sources for its work on the identification and monitoring of toxic species. This program has now been extended into a joint venture with SCOR and ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) to include the global ecology and oceanography of HAB (GEOHAB). The need for observational data is so fundamental to all science programmes that it is inevitable that the arguments about linkages to GOOS will be repeated for each element of the programme. The OSLR programme has accepted responsibility for the GOOS Panel on Living Marine Resources (LMR-GOOS). The Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), which the IOC co-sponsors, has also been recognized as part of the GOOS network. The IOC is a co-sponsor of the Global Ocean Ecosystem Dynamics Programme (GLOBEC) with SCOR and IGBP and also the Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Programme. Given the variety of elements within OSLR, the Evaluation Team endorses the call from Member States for the development of a strategic plan for the future of OSLR. The Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Living Resources (OSLNR) Programme is more modest than the OSLR, but is also in urgent need of an overall strategy to guide its future development. Marine Pollution is addressed within the IOC under the joint IOC-UNEP-IMO Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment (GIPME) Programme. GIPME has largely undertaken the responsibility for the design of the Health of the Ocean (HOTO) module of the GOOS Programme. This is a programme that has addressed its objectives and organization and over the last several years has been substantially revised. The rather cumbersome Intergovernmental Panel has been replaced, following a decision by the Assembly in 1997, by a 20 GIPME Expert Scientific Advisory Group (GESAG) that incorporates all elements of the programme. These actions to streamline the programme appear to have been well judged. The 1997 Assembly also decided to have a discrete programme directed at Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM). This was a direct reflection of the priority for coastal issues shared by all Member States. The priority was amplified by the new management responsibilities for the EEZ created by UNCLOS. A Consultative Meeting prepared a proposal for an ICAM programme that was subsequently endorsed by the IOC Executive Council in 1998. There are five elements in the core ICAM programme: namely: interdisciplinary approaches, monitoring, information, the development of methodologies and capacity building. ICAM has the support of Member States but nevertheless presents a risk to the IOC. The scope of issues within the vulnerable coastal areas ofthe world is enormous and the number of agencies dealing with these issues is huge. The IOC cannot hope, within even optimistic limits of foreseeable resources, to cover all the expectations of its Member States. The programme will therefore have to be very specific about what it can contribute to ICAM and be equally specific about what it is unable to tackle. Although coastal issues have long been cited as priorities within the IOC, the ICAM programme is a recent initiative that needs to be monitored closely and critically. The Evaluation Team was conscious of the need to maintain credible and well-focussed science programmes within the IOC. The Ocean Science programme clearly requires strong and respected leadership and needs to have its collective opinion heard in the other programmes. The professional secretariat for Ocean Science currently consists of a Head of Section and one other staff member, two seconded staff and five consultants. Because of the heavy workload of program management and coordination, much of the scientific leadership must inevitably come from designated experts, elected chairs ofworking groups and committees, consultants and so on. The ocean climate programmes are demanding on the IOC, but critical to its future role. The direction for these programmes is largely found outside the IOC: but commitment and direct involvement of Member States are needed for their successful implementation. At the moment, the successesof recent El NiAo forecasts are fresh in the minds of many governments, UNESCO and its IOC cannot afford to be absent from the debate on these critical global issues and therefore must keep Member States fully informed of, and committed to, the climate programme and its impact. Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM) also has to be watched closely, but from a different perspective. Its high priority amongst Member States could possibly lead to a proliferation of demands and programmes that exceed the capacity of the available resources. High expectations lead to severe disappointments and frustrations when desired objectives are not achieved. Finally, the whole Ocean Science Programme could benefit from an expert strategic review of where it is heading and how its various components can progress within a common framework that exploits and enhances the role of the IOC. In a time of scarce resources, such a plan is necessary to maintain a balance amongst the many competing activities. 3.3 Operational Observing Systems There have been few programmes that have seized the IOC with the attention that has been given to the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS). Perhaps it has achieved high priority because of the breadth of its clients, in climate, living resources, ocean health and coastal management; perhaps becausethe role of an intergovernmental organization lends itself to tackling harmonized global programmes; or perhaps because of the obvious need for such a system to underpin all 21 aspects of ocean science and services. Whatever the reason, GOOS has emerged as a clear focus of IOC activities over the past decade. The Secretariat Section responsible for the Operational Observing Systems Programme has a Head who is also Director of the GOOS Project Office (GPO), a programme specialist, three seconded staff and two consultants. An appointment has also recently been made to the new Regional Programme Office of the IOC in Perth (Australia) to focus on GOOS implementation in the region. Over the past few years, the Programme has clearly made strides to become more effective and valuable. GOOS has the advantage ofbeing identified and encouraged in other intergovernmental fora, such as Agenda 21 of the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) and subsequently in the follow-up deliberations as part of the UN Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD). The programme is also recognized as the ocean component of the joint WMO-IOC-UNEP-ICSU Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) and receives visibility in such fora as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) and the World Climate Programme (WCP). Regionally, the benefits associated with observing the oceans have been recognized for specific phenomena such as the El Nina (the GOOS TAO (Tropical Atmosphere Ocean) array in the Equatorial Pacific) and for broad regional applications in ocean and coastal management under initiatives such as EuroGOOS, NEARGOOS, and others that are in various stages of planning such as MedGOOS, PacificGOOS, BlackseaGOOS, GOOSAfrica and so on. All this potential has not yet materialised as the needed ocean coverage and services that are the ultimate objective of GOOS, nor is it reasonable to expect that this will be achieved overnight. The GOOS development has been planned to build on existing capabilities and networks, to develop in regional areas where specific priorities can be identified and resolved, to investigate technologies and methodologies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of ocean measurement and monitoring systems and to build capacity and capabilities in developing countries in order for them to recognize potential benefits and contribute to their attainment. Recent developments within the IOC have consolidated many of the observational elements within GOOS. IGOSS and GLOSS and the former WMO Commission for Marine Meteorology have been brought into the Joint IOC-WMO Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM), that will serve as the main technical committee for GOOS. JCOMM will also encompassthe IOC Ships-of-Opportunity programme and the WMO Voluntary Observing Ships (VOS) programme, the Data Buoy Cooperation Panel and others. The decision to establish JCOMM was ratified by the IOC Assembly and the WMO Congress only in 1999 and so it is too early to evaluate its success. However, it has clear potential to reduce the administration involved in the formerly separate observational programmes of the two parent organizations. GOOS has a new GOOS Steering Committee (GSC) and has developed a Strategic Plan and Principles. It has developed clear objectives combined with a realistic developmental plan whose emphasis is on an holistic issue-driven approach. It has a major pilot project (GODAE cf pl 8) designed to demonstrate the assimilation of data and the capability of providing ocean services in real-time. In preparation for this project, GOOS is also carrying out a feasibility study on an array of automated profiling floats, and 3,000 of these are expected to be deployed in the ARGO experimental programme. 22 GOOS is comprised of modules addressing climate, living resources, coastal management, pollution and ocean services. The design of the climate observational programme has led the GOOS development becauseof the clear existing requirement. The Health ofthe Oceans (HOTO) pollution model is being planned by GIPME as already discussed above under Ocean Science. The design of HOT0 is already at an advanced stage. The living resources and coastal modules are more complex and the design phase is still under development, also with the assistance and direction of other IOC programmes. The close linkage between GOOS and GCOS is maintained by a Memorandum ofunderstanding that was revised in 1998. The co-operation, includes joint work on the design of climate observing systems, joint sponsorship of the Ocean Observations Panel for Climate (OOPC), the Joint G30S Data and Information Management Panel (JDIMP) and the Global Observing Systems Space Panel (GOSSP). The new JCOMM joint arrangement will have management implications for GCOS and these other panels, that have been accommodated in the organization, but again the implementation has not yet fully taken effect. The role of the Intergovernmental Panel for GOOS (I-GOOS) is not always well understood. GOOS cannot be sustained as an operational system without the support of governments, but the representation of national delegates to I-GOOS is usually at an expert level. It is considered that I-GOOS would benefit from representation by national delegates at a higher level of national coordination responsibility within Member States. Capacity building to allow Member States to participate in and benefit from GOOS has emerged as a high priority. Member States are anxious to avail themselves ofworkshops and other material that is ofobvious usefulness in dealing with the growing coastal conflicts and management issues. It appears that the very success of GOOS presents one of its biggest problems. GOOS is so fundamental to every ocean issue that the demand on staff and expertise is enormous. GOOS ultimately is a tool to serve other programmes and projects and needs to be managed in this way. The objectives of GOOS must be supported by the other programmes and GOOS must, in turn, ensure that it is responsive to the priorities from those programmes. Despite the recent streamlining of the operational IOC programmes, the number of panels, committees and other meetings associated with GOOS is too high for the existing staff resources of the GPO and for the national experts associated with the programme. To a large extent, the integration of expertise from other IOC programmes into GOOS has been addressed very well. It is difficult, however, to rationalize the very real demands of individual programme elements with the larger picture of overall IOC objectives. The common objective and organization of GOOS has imbued the staff of the GOOS Programme Office with a closer liaison and esprit de corps than may be found in some other areas of the organization. GOOS presents the optimum potential for the IOC to attract support and resources. It has a direct cost-benefit potential for all Member States regardless of their state of development. The present structure has momentum and visibility which needs to be maintained. The Evaluation Team found a high level of optimism that, well supported, GOOS will deliver enormous benefits to the global community over the next few decades. 23 3.4 Ocean Services The Secretariat Section responsible for the Ocean Services Programme is small and consists of a Section Head, who is also currently the Deputy Executive Secretary of the IOC, one permanent professional, one consultant who is working on Ocean Mapping, one consultant on IODE/GOOS and two general service staff. Under the structure of past years, an Ocean Services Section included the Integrated Global Ocean Services System (IGOSS), the Data Buoy Cooperation Panel (DBCP) and the Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS). These were then transferred as existing components of GOOS and recent changes within the Secretariat further consolidated these and other programmes under the Joint WMO/IOC Technical Commission (JCOMM). The Evaluation Team was aware that before and during the International Year ofthe Ocean (IYO) in 1998, it was the staff of the Ocean Services Programme that supported and managed the extremely heavy additional work-load of information and programme management. Some of the vitally important follow up to IYO is still in need of attention. The major programme under Ocean Services is the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE), which was established in 1961 to facilitate the exchange of oceanographic data and information amongst Member States and to meet their data management needs. The IODE System forms a world-wide network of ocean data centres (Designated National Agencies and National Oceanographic Data Centres) some of which act as regional or global centres for specific tasks. Representatives attending IODE are usually Directors or experts from the national centres giving the deliberations of the meetings substance and guaranteeing the implementation of decisions made. The number of such centres is approaching sixty, which is a high proportion of the active Member States of the IOC. The System gives world-wide accessto millions of ocean measurements and observations that need international formats and standards to facilitate their exchange and use. The programme has recognized the emergence of the information age and responded with a programme on Marine Information Management (MIM). As would be expected in an area basic to the development of ocean expertise, the requests for technical assistance for marine data management and information services are demanding. The data policy for the IOC is to protect and preserve free and open access to ocean data. This will be vitally important to the entire future of international oceanography. The IODE programme continues to pay attention to existing past datasets with its very successful Global Ocean Data Archeology and Rescue (GODAR) programme. Over the past several years, fifty countries have taken part in six regional GODAR workshops, resulting in an impressive increase in the number of data profiles now available. The work of GODAR is continuing as a priority programme of IODE. IODE was established to handle archived ocean data and, in the early days, this meant data that could be many years old. Some years later, when a requirement was seen to handle data being transmitted in real-time or near-real time, the IOC, jointly with WMO, established a new Working Committee for IGOSS (Integrated Global Ocean Station (later Services) System). Over the years, as more observations became automated, and as new technologies were contributing vast amounts of data, the distinction between real time and archived data diminished and the two committees increased joint activities. End-to-end management of data from observation through quality control to final archive became a reality through such co-operative programmes as the Global Temperature and Salinity Profile Programme(GTSPP). IODE supplies datasets to scientists and 24 institutions around the world. These are continually improved and up-dated through the addition of new data from observations and projects such as GODAR. The Marine Information Management (MIM) has redesigned the IODE website, established a Global Directory of Marine and Freshwater Professionals (GLODIR) and prepared a metadata base development tool. Many of the initiatives of the IODE are contributed by national data centres. The global network of Responsible National Oceanographic Data Centres (RNODCs) usually involves the more capable of the national centres, that undertake specific regional or global tasks and make the results available to all. The full IODE Working Committee meets at intervals of several years but the intersessional work is carried out by four groups of experts - on TADE (Technical Application of Data Exchange), on MIM (Marine Information Management). on IGOSSIODE end-to-end data management systems, and a task team on biological and chemical data. The leaders of these groups, the GODAR Project Leader and the Directors of the ICSU WDCs on Oceanography and Marine Geology and Geophysics form the IODE Bureau. IODE has always paid close attention to capacity building activities. Perhaps some ofthe greatest achievements have taken place in Africa where partnership with donor agencies has allowed the programme to develop networks of ocean information and data exchange in both eastern and western Africa. These networks promote regional cooperation, encourage publications, provide access to ocean science literature and data and raise the capability of African countries in oceanographic data monitoring and marine research. One criticism that has been voiced numerous times over the years by the data experts associated with the IODE, is that, too often, other programmes tend to establish their own specific data programmes to satisfy their individual needs. The IODE experts see this as duplication and “reinventing the wheel”. They also worry that such data may not find their way into the ocean data archives. Opposing arguments cite special requirements, the need to manage the discrete data set in a timely fashion and a worry that, if they used the existing IODE framework, they might not be able to easily access their special data sets. Obviously, merit exists in both views. It is the present aspiration of IODE to be recognized as the ocean data standards authority. Then others could be free to establish individual data programmes as long as they adhered to the rules and standards laid down by the IODE. Perhaps this is the ideal with the future IODE performing more policy setting and less management. IODE will be stronger if its competency is drawn upon by all IOC programmes needing data management components for their projects and programmes. The Evaluation Team was aware that the IODE has been a solid performer for the IOC over the years and that the present IODE leadership is determined to establish the IOC as the world authority for ocean data standards and to move forward with the electronic age. It will be important, however, that this be achieved in close coordination with other key agencies and, in particular, through the facilitating role of the IOC-WMO JCOMM. Another longstanding and successful programme from the perspective of the countries of the Pacific Basin is the International Tsunami Warning System (ITSU), which facilitates an intergovernmental programme to warn of, and mitigate the impacts of, devastating tsunamis. Through the tsunami programme, IOC has contributed effectively to the objectives of the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR). Although the ITSU programme has been centred on the Pacific for many years, there is, of course no special regional significance to this, beyond the proneness of the region to earthquakes and 25 hence to tsunamis. In general, Members not prone to tsunamis have tended to regard ITSU as of relatively low priority. Recently, however, other regions have been requesting more attention to the forecasting of tsunami, and of storm surge propagation, in their respective areas. The resources allocated to manage the ITSU programme have never been generous. The problem is now compounded by the demands to extend the work outside the Pacific Basin to other regions. The ITSU programme covers all aspectsof a tsunami warning network from mathematical models of tsunami propagation to programmes to alert the community. Perhaps it is time to examine this very successful programme and to determine what should be the responsibility of the benefiting Member States and what would be the most useful role for the IOC. In IOC programme terms, Ocean Mapping was traditionally included under Ocean Science, but is now part of Ocean Services. It is a programme that has been very successful at minimal cost to the IOC. Ocean Mapping is a programme carried out in partnership with the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). Producing maps and charts of the sea-bed is very expensive, but the need for charts to support marine transportation has led to an extensive network of agencies throughout the world which co-operate largely through the IHO. This expertise was extended into deeper waters as interest in the deep ocean developed. Much of the expense of publishing the GEBCO series of ocean charts was assumed by the hydrographic agencies. Today, the requirement for ratifying countries to delineate their offshore resources under the UNCLOS, the march of the hydrocarbon industry into ever deeper waters, the growing interest in deep-sea living and non-living resources and the need for geological information has expanded the operational interests of the hydrographic community beyond the shallow coastal waters. Accurate mapping and positioning is a prerequisite for scientific and observational activities and recent advances into electronic mapping and satellite positioning adopted for navigation are rapidly assumed into the ocean science community. Global and regional models need higher accuracy of boundary information as their resolution increases and the exchange of ocean data in all disciplines requires meta-data giving precise spatial coordinates. 3.5 Cross-cutting Activities Capacity building is an essential and critical part of all IOC activities. The Training Education and Mutual Assistance (TEMA) role of the IOC has always been of high priority. Until recently, TEMA was run as a separate programme ofthe Commission, complete with an intergovernmental committee. It has now been accepted that TEMA is best managed as a cross-cutting activity that must be seen as part of each and every IOC programme. This is viewed within the Commission as a positive step and one that will result in a more effective use of IOC TEMA resources. It will be important, however, to ensure that the shift from recognition of TEMA as one of the three traditional pillars (science, services, TEMA) of the IOC does not lead to less focussed attention on the needs of the developing countries. As a cross-cutting programme, TEMA activities will be planned and managed within, and as part of. the other programmes. In fact, with limited resources, it should perhaps be a criterion that IOC TEMA should be limited to areas which directly support participation in IOC’s own programmes, such as the highly successful ODINAFRICA (Oceanographic Data and Information Network for Africa) where the dollars spent will develop capabilities that will be used to increase participation in data management programmes. Collectively, the relative strength of TEMA is apparent. During 1998. for example. the IOC supported fifty-eight TEMA activities mostly in the form of training workshops and, in total. spent US$800,000 on TEMA activities, of which about 60% came from extra-budgetary resources. 26 The IOC’s efforts to utilize modem methods and educational materials in TEMA are to be applauded. It is recognized that nothing that the IOC can do in this area will be sustainable without the cooperation and commitment of the recipient countries. Regional activities provide a way to make more effective and efficient use of funds. Wherever possible, mutual assistance programmes within regions should be supported. There appears to be general agreement that a promising start has been made to address the challenge of capacity building within the IOC. The TEMA programme may need to become more focussed as a result of the new arrangement, with the experts within the individual scientific and technical programmes having a clearer idea of requirements for the training and assistance required to meet priority programmes. Each IOC Science and Services programme should now take over stronger responsibility for capacity building actions, identifying needs, establishing contacts and mobilizing resources. The Evaluation Team found that there has been virtually no auditing of past TEMA activities to record past successesand failures and to learn from these experiences. Thus a desirable role for IOC headquarters would be to assist in TEMA activities and courses through assistance with training methodologies, maintaining adequate databases of activities and in evaluating their performance. 3.6 Regional Activities The implementation of IOC programmes through the collective efforts of its Member States has always been a central theme of the IOC. A second has been based on the belief that the programmes can best be handled through a regional approach, However, after many years of attempting to deliver regional activities, the results are definitely a mixture of successand failure. The IOC has seven major regional bodies with regional programme responsibilities. Two ofthese are Sub-Commissions (WESTPAC and IOCARIBE) and five are Regional Committees (IOCINCWIO, IOCEA, IOCINDIO, IOCSOC and BSRC). In addition, the IOC has specific programmes in other regions - South-East Pacific, South-West Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea, the Gulf/Red Sea/Gulf of Aden and the Caspian Sea. The strain on IOC resources to maintain these regional programmes has been substantial and the Evaluation Team found a generally equivocal assessment of their success. The role of the regional bodies is twofold , to facilitate participation of regional Member States in the IOC global programmes, and to address the identified regional programme priorities of the Member States. The IOC regional bodies are of special significance in terms of their particular concern with the needs of the developing country Members of the IOC. Ideally, much more effort should be directed by the Secretariat and the developed Member States to implementation of the programme priorities of the regional bodies. The core funding needed to support regional activities is not excessive. One or two professionals and supporting staff could provide most of the co-ordination required for a Regional Office. The regional countries themselves could provide the collective effort needed to address programmes selected to focus on regional elaborations of the global IOC Programme, to administer regional groups of experts and to service the Regional Sub-Commission or Regional Committee sessions. Regional countries should second staff. Headquarters staff support is needed also, however, to provide guidance and to maintain a liaison with the overall IOC Programme. 27 What does need to be addressed, of course, is how the regional body decides on its programme of activities. The regional Members should dictate their own programmes within the context of the overall guidance and assistanceofthe IOC Programme. Their programmes should be practical and realistic. The regional Member States should also feel that their own experience and needs can be brought to bear on the global programmes through the participation of their delegates in the IOC governing bodies and of their experts in the planning process for the global programmes. A substantial part of the IOC capacity building activities is implemented in the regions. If the IOC could provide a better structure for articulating the collective needs of regional Member States, so that the priorities reflect the real regional needs, then a greater flow of resources could reasonably be expected from the donor community. The regional meetings could also be improved with better communication and input in the preparation process. Member States should feel an ownership ofthe agenda and the results should address the priorities identified. There is now sufficient indigenous capacity in several regions to identify priorities, programmes and projects. IOC staff need to be present to explain the possibilities and limitations of the global programmes and the potential for assistance. Mutual assistance should be an important agenda item in addition to external support and funding. Greater ownership of the regional agendas and programmes will lead to more of a ‘“partnership type” meeting where delegates and potential donors could meet on more equal terms and where linkages could be encouraged between the regional IOC bodies and the more politically oriented agencies such as OAU in Africa, OAS in Latin America, APEC in WESTPAC and SPREP in the South Pacific. It is clear that presently the IOC regional bodies are mostly unknown entities to other regional governmental and NGO bodies with whom they could form constructive partnerships. This impression was reinforced by the Evaluation Team’s review of WESTPAC. 3.7 Conclusions and Recommendations There is no doubt that the IOC Programme is an extremely important part of UNESCO’s overall scientific programme in the earth and environmental sciences and that, together with the meteorological and hydrological programmes of the World Meteorological Organization, these constitute the centrepiece of the international intergovernmental effort to better observe, understand, predict and protect the total earth system. Based on the available documentation and briefings on the IOC Programme and its general findings summarised above, the Evaluation Team concludes and recommends as follows: Conclusion 3. The IOC Programme has an enviable record of achievement over many years but has become too unfocussed and thinly spread to be adequately carried out with the resources available. Although the recent restructuring of the Programme has provided a much more appropriate framework for conduct of the scientific work of the IOC and several individual components of the Programme are now progressing well, the Programme is in need of a much more strategic and focussed leadership if the IOC is to deliver the results which Members expect of it over the coming decade. . C3.1 The recent regrouping of the IOC’s scientific and technical programmes into Ocean Science, Operational Observing Systems and Ocean Services has significantly improved the IOC programme structure but the IOC currently lacks a well developed programme planning, management and evaluation framework. 28 C3.2 c3.3 c3.4 C3.5 C3.6 c3.7 C3.8 c3.9 The IOC Ocean Science Programme has served the Commission and IOC Member States extremely well but it is very thinly spread and in need of expert review and refocussing. IOC has played an effective role in the international planning and coordination of climate research and its joint sponsorship of climate programmes with WMO, UNEP, ICSU and other international organizations has greatly facilitated a cooperative and integrated international approach to climate research. The IOC has performed a valuable role in participation with other organizations in the study of marine pollution but it needs to avoid duplication and overlap with other international programmes. The planning and development of GOOS is proceeding very well but the need to support the wide range of planning and interagency coordination activities is placing excessive demands on the GOOS Project Office. The International Oceanographic Data Exchange (IODE) programme has been very effective in establishing a common framework and standards for exchange of vitally important ocean data. It is performing a continuing valuable function in ensuring that IOC moves with the times in the use of new technologies for data archival and exchange. The IOC Tsunami Warning (ITSU) programme has been very successful but its extension into regions beyond the Pacific basic will require more resources than can be expected to be available from within the IOC Secretariat. The more direct involvement of potential beneficiary countries will be essential. The decision to treat capacity building as an integral part of all of IOC’s scientific and technical programmes, and thus as a cross-cutting activity, is appropriate and timely. Because of its importance to so many Member States, IOC’s TEMA (Training, Education and Mutual Assistance) activities need to be carefully assessedto ensure maximum efficiency and effectiveness in the overall use of resources. Despite its unquestioned importance to Members, the regional programme of IOC has not been easy to plan or implement effectively. A greatly increased commitment of Members is needed to focus the regional programme on priority issues with expert staff seconded by Members to support the regional effort, with only general coordination from IOC Headquarters. Recommendation 3. That the IOC governing bodies and Executive Secretary review and revitalise the IOC programme structure and its planning, priority setting and management systems in line with its new statutes and based on modernised and streamlined arrangements for consultation and communication within the IOC Secretariat and Regional Offices. . R3.1 That the IOC give very high priority to further review of its scientific and technical programme structure and management with a view to implementing a more strategic and systematic approach to program planning, management and evaluation. . R3.2 That the IOC prepare an overall strategic plan for the Commission’s future role in ocean sciences with particular emphasis on ensuring that the plan is realistic and focussed on the identified priorities of Member States. . R3.3 That the IOC maintain and strengthen its role, in partnership with other relevant international organizations, in sponsoring international climate research and, particularly, in involving the relevant science agencies of its Member States in the coordinated research effort. . R3.4 That GIPME (Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment) technical design ensure that the future role of the IOC is compatible with other 29 R3.5 R3.6 R3.7 R3.8 R3.9 international mechanisms for dealing with marine pollution whilst also preserving a clear and appropriate role for the IOC. That the GOOS Steering Committee (GSC) and GOOS Project Office (GPO) continue to explore ways of reducing the complexity of the GOOS organization and the number of GOOS-associated meetings. That the IOC continue to strongly support the work of IODE (International Oceanographic Data Exchange) through the Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM) and in other ways and encourage its efforts to establish widely accepted global standards for marine data. That the International Tsunami Warning (ITSU) programme be examined to establish the extent of the continuing role needed of the IOC with Member States of regions desiring support being encouraged to undertake more direct responsibility for resourcing of the programme. That the IOC efforts in Training, Education and Mutual Assistance (TEMA) be strongly endorsed and strengthened and that both donor and recipient Members be encouraged to give priority to TEMA activities as part of their participation in IOC scientific and technical programmes. That the IOC governing bodies and Regional Sub-Commissions and Committees give priority to redefining the IOC approach to regional programme planning and implementation with a view to ensuring that IOC programmes focus clearly on regional priorities. ADMINISTRATION AND RESOURCES In addressing the requirement to evaluate the overall administrative performance of the IOC in carrying out its mandate and implementing its programmes (“provide an assessment of the IOC administrative effectiveness and efficiency”), the Evaluation Team found it necessary to focus on two major aspects of the operation of the Commission: . the performance of the IOC Secretariat; . the overall resourcing of the IOC and its programmes. The Team also examined, in greater depth, one particular aspect of the operation of the Secretariat, the WESTPAC Regional Office in Bangkok, where several of the difficulties relating to the overall operation of the IOC assumed particular significance. 4.1 The IOC Secretariat The IOC Secretariat (Appendix E) consists of a small group (currently 21) of permanent staff, who are employees of UNESCO, complemented by a temporary band (also currently 21) of seconded experts and consultants - all under the leadership of the Executive Secretary (of Assistant Director General rank in UNESCO) who is supported by a Deputy Executive Secretary (who currently also heads one of the three major programme sections of the Secretariat). It should be stated at the outset that, from national questionnaire responses, stakeholder submissions and interviews and confidential opinion surveys in the marine science community, the Evaluation Team found a widespread appreciation among Members and the scientific community of the professionalism, dedication and efficiency of the Executive Secretary (and his predecessor) and the staff of the IOC Secretariat; but an almost universal recognition that the Secretariat is far too small and thinly spread to carry out the enormous range of scientific, technical, policy, liaison and management functions that Members expect of it in supporting the work of the IOC governing bodies and in the planning and coordination of the IOC Programme. 30 The current staff situation in the Paris Headquarters is a particular cause for concern. Several posts are empty or occupied on an ad hoc basis and the small group of permanent staff is spread extremely thinly across the entire responsibilities of the Commission. Although the maintenance of a vacancy factor to provide some funds for employment of consultants has enabled the Executive Secretary to accessa wider range of skills than might otherwise be available, the effort in hiring consultants to maintain adequate staffing levels consumes a significant fraction of senior staff time. Additionally although, once hired, the consultants provide a much needed temporary relief in the work load, this does not afford a long-term solution, which can only be achieved with an adequate number of highly qualified permanent personnel. A positive feature of the situation that contributes to some alleviation of the staffing situation is the provision of secondments by Member States. Several Member States continue to provide support to the IOC Secretariat through secondment of staff (Australia, Brazil, France, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, USA) and associate experts (Denmark and Japan). There are also financial provisions to the Special Account/Trust Fund which enable the employment of some additional staff. However, while financial support for the IOC has remained relatively steady over the past decade, secondments to the Secretariat from Member States have decreased. Renewed efforts should be made to make Member States more aware of the benefits that accrue to Members from secondment of personnel to Paris or their attachment to IOC Regional Offices. These benefits are as much in the training of the respective staff as from the direct outputs of the programme itself. The comments received by the Evaluation Team on IOC management capabilities included many complements and some surprise that such a small organization, with limited resources, could produce the volume of publications, arrange the number of meetings and run the variety of programmes that it does. Most respondents recognized the restrictions of operating within a UN system that is, itself, not as well equipped as it might be to respond to today’s global needs and expectations. Stakeholder comments on IOC staff efficiency range from glowing praise to disappointment. Clearly, such comments are coloured by individual contacts and experiences and the standard of staff performance is not uniform. Although it is recognized that the workload within the Secretariat is already severe, indeed near crisis point, there is a perceived need for a more systematic way of motivating staff and maintaining performance by rewarding productivity and dealing with under-achievers. This is an essential part of good management practice which has been difficult to maintain given the senior staff workload situation which currently exists. Management skills need to be stressed. In a small organization addressing complex issues, it is often easier for managers to deal with matters themselves rather than take the time to delegate and supervise. But quality then suffers because the manager eventually gets overloaded or is absent too frequently and the administrative and management duties are neglected. This, clearly, has been a problem for the IOC. Staff continuity also continues to be a serious problem. Secondments from Member States and the temporary necessity of hiring consultants, inevitably leads to higher turn-over of staff, loss of corporate knowledge and time lost in training and knowledge acquisition. The problem is clearly linked to the present constraints on financial resources, but recognition of the issue can guide the Secretariat in its negotiations with Member States for secondments and in the process of hiring temporary personnel. 31 The Evaluation Team considers that the often-heard criticism, that the Commission has too many programmes, is an unfair charge to lay at the door of a Secretariat that must follow the decisions and priorities set by Member States. The number and variety of the programmes within the TOC may be confusing to those viewing the organization from outside, but is largely the product of a lack of collective discipline of Members in the governing bodies of the Commission. It is true, however, that the Executive Secretary has some flexibility in the way those decisions are implemented and the Team was pleased that he is already taking steps to restructure the management of the Secretariat to better reflect the lines of authority and to reduce the perceived complexity. It is too early to say how beneficial such improvements will be, but it is to be hoped that the introduction of the new management structure will lead to: . a transparent and more understandable distribution of responsibilities; . an overall reduction in workload; . enhanced personnel management; . improved management of programs; . more explicit accounting for resource use; . a more defensible and manageable allocation of the budget, and; . more effective longer-term strategic planning. One particularly important management issue in the Secretariat relates to the previously mentioned lack of strategic planning. At the most general level, the IOC needs a clear and simple vision statement to guide and motivate the planning and management of its programmes. Not all management concerns with the IOC relate to its structure and programmes. A perennial complaint relates to the tardiness of documentation preparation and distribution for meetings, which reduces the time for preparation within Member States. The production and delivery of written material is a severe drain on the time of the overworked staff and making the process more efficient and effective would benefit the entire organization. The use of electronic information techniques has already provided some relief on this front and hopefully will lead to improved access and availability of information. On the other hand, attention must :still be paid to the number and size of documents and the pertinence of the content. It is a difficult balance to maintain between necessary and sufficient information. There is some support among stakeholders for a “publishing on demand” approach as a way to save both money and storage space. The administrative effectiveness and efficiency of the IOC Secretariat is a function of the boundary conditions within UNESCO under which it operates. Despite improvements and considerable mutual goodwill, there are still problems with the interface of administrative management between the IOC and its parent organization that severely prejudice the overall work of the Commission. The Executive Secretary must continue to work with his counterpart in UNESCO Administration (ADG!ADM) to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of this relationship. To some extent, and despite its professionalism and acknowledged commitment, the IOC Secretariat lacks a performance-related culture. While it should not go overboard with performance management initiatives for their own sake, it does need to embrace a set of simple performance indicators against which its activities can be measured. This will help to identify the weak areas that either need additional support or should be cut. 32 Attention to management detail could be productive. Having adequate computer equipment and all staff well trained and comfortable with modem electronic methods, should reduce both work loads and the expensive use of phones and faxes. More advance planning could help to reduce travel costs. Better office electronic information systems would improve liaison, reduce search time and lessen the chance of duplication. Standardized training and other manuals would save time wasted on repetitive learning curves. Strong leadership and management of the IOC Secretariat is needed. Pending the availability of additional resources, clear boundaries must be drawn and limits must be set around the tasks that the IOC assumes.Doing a few projects well brings credit to an organization. Doing many projects poorly brings only skepticism as to future capabilities and worth. Difficult choices may have to be made. The Evaluation Team was convinced that the Executive Secretary is fully aware of the need for such choices to be made. 4.2 The WESTPAC Office As part of its overall Evaluation of the IOC Secretariat, the Evaluation Team was asked by the Executive Secretary to undertake a more in-depth assessment of the IOC WESTPAC Office in Bangkok, Thailand. Two members of the Evaluation Team (Field (Leader) and Zillman) carried out the assessment over the period 2-4 December 1999 in the context of a review of the overall operation of the WESTPAC Sub-Commission and the WESTPAC Programme. The essential findings of the Team are summarised in Appendix J and the full report of the WESTPAC Evaluation is available as a separately-bound annex to this report. In summary, the Evaluation Team found that the WESTPAC Office in Bangkok performs a very useful function in the region and should be maintained. It is well located in near optimal conditions to serve the needs of WESTPAC and its Members and the present arrangement under which it is hosted by the National Research Council of Thailand is welcome and appropriate. The Team found, however, that the efficiency and effectiveness of the Office could be enhanced by more systematic resource planning in the Office and increased devolution of budgetary responsibility from IOC Headquarters in Paris. To fulfil its potential, the Office needs dynamic leadership with vision, initiative and the ability to inspire cooperation in the scientific community and raise the profile of IOC within the region. 4.3 Resources and Resource Management As elaborated in Appendix F. the IOC funding comes from the Regular Budget of UNESCO (about 60%) and from the IOC Special Account (about 40%), the latter being made up mainly from contributions from Member States. The Regular Budget funds support all of the costs for permanent staff posts (which account for about a third of the total IOC budget) and the Special Account adds another 15% for seconded positions and consultants. Thus, personnel costs take almost half of the funding with the remainder (made up of approximately equal amounts of Regular Budget and Special Account monies) available to address the programme requirements. Despite the efforts of UNESCO to maintain its support for the work of the IOC, the burgeoning new demands on the Commission. emanating from the various international environmental conventions and the pressures for rapid implementation of the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), have generated an increasing resource gap that makes it very difficult to meet Members’ expectations of the Commission. 33 Some relief from additional extra-budgetary funds from donor countries does occasionally enable the IOC to carry out more capacity building activities than would otherwise be the case. However, as the only UN specialized agency for science and services for the oceans, it might reasonably be expected that rather more support would have been forthcoming from other sources wishing to avail themselves of the expertise within the IOC programmes or wishing to strengthen the work of the IOC in particular areas of mutual interest. The Evaluation Team was aware that one of the impediments to securing significantly increased funding for IOC programmes in the past has been the lack of a substantial body of rigorous economic analysis and case study information demonstrating the economic benejits of IOC activities to Member States, to complement the undoubted social and environmental benefits from effective international coordination in monitoring and understanding of the oceans. In order to help it to focus attention on the urgent need for such information and to assist Members in ensuring more informed decision-making at the national level, the Team sought consultant assistance in developing an initial framework for cost-benefit analysis of IOC programmes and a preliminary survey of evidence from published studies of the economic benefits of marine science programmes. The report of the consultant (Mr Martin Brown) is available separately as an annex to this report and its Table of Contents is provided at Appendix K. It appears that, while cost-benefit analysis is a potentially useful tool for promoting economic discussion of marine science and technology and should be vigorously promoted by the IOC, the literature is not as well developed as for meteorological science and services and the work of the World Meteorological Organization. There are clearly difficulties, also, in separating cost-benefit considerations applying to the work of the IOC governing bodies and Secretariat and the coordinating and catalytic work of the IOC on the one hand and the IOC-related marine science and technology activities of IOC Member States undertaken for strictly national reasons, on the other. The limited information so far available suggests that there are compelling economic grounds for increased UNESCO and Member State investment in the work ofthe IOC. One particularly useful role which could be assumed by a strengthened IOC Secretariat would be to serve as a sponsor and focus for development and implementation of a more rigorous framework for evaluation of marine science and technology and IOC programmes as an aid to improved priority setting and resource allocation within the IOC itself as well as in the marine science and technology programmes of its Member States. There is no capability within the Secretariat devoted to fund raising. Many of the professional staff have done well at attracting extra-budgetary funds, but it is time consuming and a specialized task requiring specialized skills. There has, in the past, been some fairly strong Member State criticism of IOC financial management and budget presentation. The Evaluation Team was informed that the financial management within the IOC is improving, but it was also aware that it is difficult to maintain tiscal responsibility when most of the financial machinery is external to the organization in another part of UNESCO. The Team concluded, however, that there is more that the IOC could do. The IOC does not make long-term budgetary plans. The reason for this has been that it has been impossible to predict the level of funding either from the Regular Budget or Special Account. Recently. however, the Director-General bestowed an “incompressible” budget on the IOC that does offer some protection against unexpected reductions, and the contributions from Member States have remained relatively steady. The reasonable assumption that at least the 34 present level of funds will be available over a five- to ten-year term has, in fact, helped the IOC to establish a more stable planning framework. The presentation of budget information to Member States is still, however, inadequate and obscure. Although the most recent Twentieth Session of the Assembly received a clearer picture of the budget and had a better financial debate than at any time in recent years, much greater clarity is still needed. It is extremely difficult to ascertain, with any confidence, what has been spent on travel, on translations, on meeting arrangements, on publications, etc. This level ofdetail may not be necessary for the general plenary debate but, without such information, it is difficult for the governing bodies to take properly informed decisions on the best use of the resources of the Commission. The IOC is not a funding agency. Although it is cost-effective, at times, to support an external workshop or conference of particular relevance to the IOC Programme, by far the largest part of the IOC budget should be addressed to the IOC activities themselves. Many approaches have been considered for increasing the resources at the disposal of the IOC. A suggestion to impose a voluntary contribution system on Member States, according to their ability to pay, received little support from Members. This may not mean, however, that such a scheme will not emerge in the future when the benefits from ocean services become more evident. The IOC needs to form stronger links with the donor community and industry as a matter of urgency. The latter would be a new development for the IOC. Partnerships with the funding communities are long overdue. Where possible, donors might be encouraged to contribute to the policy forming committees of the IOC to enable the programme to take advantage of potential opportunities. Another way would be to prepare documentation indicating how the IOC can meet the needs of new resource communities. An obvious problem is that searching for new resources and new donor partnerships takes a lot of effort especially for an organization that is virtually starting from the beginning. Eventually one would hope that the funds produced would more than compensate for the expended effort, but there are real start-up costs. Getting the right people seconded to the IOC to prepare proposals is one way forward and perhaps assistance could be obtained from such organizations as the World Bank or other funding agencies. The IOC programme underpins many of the objectives pursued by these agencies. This is an area where UNESCO itself should be able to help. Notwithstanding the widespread recognition that the IOC is severely under-resourced, there is no firm estimate presently available of the annual amount required to adequately support the essential elements of its scientific programme. It may, indeed, be impossible to arrive at a precise figure for the total requirements. However, by identifying specific milestones and objectives, realistic estimates are possible for the short- to medium-term. These suggest the need for an approximate doubling of the IOC Budget (Regular Budget plus Trust Fund) from around $5.5M pa to $1 IM pa over the next two to three years. 4.4 Conclusions and Recommendations The Evaluation Team found itself in considerable admiration of the past achievements of the IOC Secretariat in very difficult circumstances but it was also very concerned that the secretariat lacks a sound programme planning and management framework and that the entire IOC operation, including especially the Secretariat, is critically under-resourced. Given the enormous benefits that would flow from having just two or three extra people in each of a few key areas, the 35 Evaluation Team believes that a major upgrading of the work of the IOC is well within the management flexibility of UNESCO and IOC Member States. The Team concludes and recommends as follows: Conclusion 4. The IOC, as an organization, and, in particular, its Secretariat, are doing a remarkable job with very limited resources. However, continuation of present arrangements indefinitely is not an option if the Commission is to perform the role Members expect of it. The Commission and its Secretariat are in urgent need of improved management processes and increased resources, both from Regular Budget and external sources. . c4.1 The IOC Secretariat carries out a vitally important role with great professionalism and dedication but it lacks the resources and management systems and capabilities to adequately meet Members’ expectations of it. . C4.2 Although recent reallocation of responsibilities in the Secretariat has provided an improved framework for management of IOC programmes, the staffing situation is sub-critical in most areas with a severe shortage of core professional staff and insufficient continuity and corporate memory to ensure effective and accountable programme management. . c4.3 The secondment of staff to the Secretariat by Members for periods ranging from a few months to a few years has played a key role in maintaining the viability of several IOC programme activities and has also proved extremely beneficial to Members’ own national marine activities. . c4.4 The Secretariat lacks a performance culture and effective personnel practices for monitoring staff performance, enhancing staff motivation, recognising high performance and managing under-performance. . c4.5 The IOC cannot afford to be left behind in the use of emerging technology for internal and external communication, information management, documentation and programme management. . C4.6 Substantial Secretariat time and financial resources are consumed in the preparation of often excessively detailed and repetitive documentation which is frequently late in its availability to Members and other stakeholders. . c4.7 Despite substantial goodwill on both sides, the interface between the IOC Secretariat and UNESCO Administration does not work well and is in need of review and streamlining to produce more responsive and efficient administrative support for IOC programme management. . C4.8 The WESTPAC Office is well located and performs a very useful function but is not fully meeting Members’ expectations and needs dynamic leadership to inspire cooperation in the scientific community and raise the profile of IOC in the Western Pacific region. . c4.9 The IOC has benefited from significant extra-budgetary supplementation of the resources made available from the UNESCO Regular Budget but the overall IOC Programme is severely under-resourced and is in urgent need of increased budgetary support from both the Regular Budget (to maintain the viability of its core functions) and increased contributions to the IOC Trust Fund (to enable urgently needed programmes to proceed at a viable level). . c4.10 While available economic analysis suggests that UNESCO and its Members have much to gain from substantially increased investment in the work of the IOC, there is an urgent need for a more rigorous framework for cost-benefit analysis of marine science programmes and for a range of case studies at both the national and international level. . c4.11 The IOC’s accounting and budgetary systems and procedures are inadequate to provide the Executive Secretary, governing bodies and Members of the 36 . C4.12 . C4.13 . . C4.14 C4.15 Commission with a sufficiently clear basis for sound decision-making and effective resource management. The IOC has benefited from the recent allocation of an “incompressible” budget for its established level of Regular Budget-supported activities but requires a secure long-term resource base compatible with the substantially increased programme needed to meet the expectation of Members. The use of the IOC Special Account through which IOC Members and other donors contribute to the IOC Trust Fund (in addition to the provision of seconded staff and in-kind support) has enabled the Secretariat to maintain some support for a wide range of programmes required by Members and has proved highly beneficial to the overall work and effectiveness of the IOC. The IOC has inadequate experience in, and capabilities for, external fund raising. While it is not possible, at this stage, to establish the optimum level of overall long-term resourcing of the work ofthe IOC, it is important that the UNESCO and IOC governing bodies endorse an overall strategic approach to funding ofthe IOC Programme in line with Members’ expectations over the next 5-10 years. Recommendation 4. That UNESCO and IOC Member States be urged to strengthen their contribution to the work of the IOC through enhanced national marine programmes and increased financial and other support for the international planning and implementation of marine activities; and especially through extrabudgetary funding and the secondment of expert staff to participate in the international planning and management processes in both the IOC Secretariat and the Regional Offices. R4.1 That the Executive Secretary vigorously pursue his efforts to strengthen and streamline the overall working of the Secretariat by progressive implementation ofmore efficient management support arrangements and improved work practices. R4.2 That urgent steps be taken to increase the core professional staffing of the Secretariat with a target of increasing the permanent professional posts in the Paris headquarters from nine to eighteen within two years. R4.3 That Member States be strongly encouraged to consider secondment of professional staff to the IOC Secretariat on both a short and extended term basis, consulting with the Executive Secretary in respect of the scientific and management skills of secondees who might contribute most effectively to the achievement of both the individual Member’s objectives and those of the IOC as a whole. R4.4 That the Executive Secretary introduce an appropriate performance management system into the Secretariat and give increased priority to measures aimed at enhancing staff motivation and recognising outstanding achievement. R4.5 That the Secretariat progressively modernise and streamline its internal and external communication and information management systems and introduce appropriate management methodologies consistently across programme areas. R4.6 That a review of IOC documentation preparation and distribution be undertaken to seeif simpler, more timely and less time-consuming and less costly systems can be put in place. R4.7 That the Executive Secretary and his counterpart in UNESCO Administration be invited to explore ways of improving the efficiency and responsiveness of UNESCO administrative support for the IOC. R4.8 That the WESTPAC Office be maintained in Bangkok with significant internal reorganisation and improved arrangements for communication and coordination within the region and enhanced planning and devolution of resource management from IOC headquarters. 37 R4.9 R4.10 R4.11 R4.12 R4.13 R4.14 R4.15 That the Executive Secretary be invited to prepare a strategic resourcing plan for the highest priority work of the Commission over the next decade as a framework for increased support from the UNESCO Regular Budget and enhanced contribution from extra-budgetary sources. That the IOC should take a lead in encouraging and assisting Members and their marine institutions in carrying out cost-benefit analysis of a range of marine science and technology projects to assist in decision-making on IOC Programme funding at both the national and international levels. That. as a matter of urgency, UNESCO assist the IOC Secretariat in the implementation ofmodem cost accounting and financial management systems and procedures to enable the IOC Executive Secretary, governing bodies and Members to be provided with essential programme-based financial information for decisionmaking. That UNESCO provide an increased fixed percentage of its Regular Budget for support of the operation of the IOC. That IOC Member States and partner organizations be encouraged to contribute on a regular basis, and at an increased level, to the IOC Trust Fund to complement and reinforce the increased core capabilities resulting from stronger Regular Budget support of the IOC. That the IOC seek external assistance in strengthening its capabilities for raising funds from new sources to supplement the resources available from the UNESCO Regular Budget and the IOC Special Account. That the UNESCO and IOC governing bodies and Members endorse and support the progressive strengthening of the IOC and international marine science programmes through increased resourcing from both Regular Budget and extrabudgetary sources in the light of the IOC strategic resource plan. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS AND The Evaluation Team was extremely conscious of the limitations of its own understanding of the details of many aspects of the work of the IOC, given especially the limited time and resources available for the conduct of the Evaluation. It was greatly assisted and reassured, however, by the extraordinary amount of insightful and constructive advice and suggestions received from a wide range of stakeholders in IOC’s partner organizations and the marine community generally, and the large measure of consistency amongst the views received. While many of its conclusions may need deeper analysis and its recommendations may need refinement in the light of more detailed examination of many of the issues involved, the Team believes that there is a large reservoir of goodwill and support for the work of the IOC which is available to be tapped in the follow-up action on this Evaluation. It, therefore, reached the following summary Conclusion and Recommendation in respect of follow-up action on the Evaluation: Conclusion 5. The follow-up action on the 1999-2000 Evaluation of the IOC provides a unique opportunity for UNESCO to draw on its forty years of investment in the development o.f international oceanography, and the IOC’s own established working relationships with the many other marine science-related agencies in the international system, to assist nations to reap the enormous benetits potentially available from marine research and operational oceanography in the twenty-tirst century. Recommendation 5. That IOC’s partner agencies and programmes within and outside the UN system be invited to join in the new and more integrated approach to exploiting the opportunities 38 which recent developments in marine science and technology offer to the global community in the twenty-first century. 5.1 Conclusions In order to facilitate an integrated appreciation of the main conclusions of the Evaluation, this section draws the Evaluation Team’s conclusions together from Sections l-4 above. In summary, the Team concludes that: . The oceans represent a unique but seriously threatened global commons whose scientifically based monitoring, understanding, prediction and protection will be vitally important to community welfare and planetary survival in the twenty-first century (Conclusion 1). . The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) has responded effectively to the changing national and international needs for coordination and cooperation in oceanography and its current statutes and its governance and working methods are appropriate to the contemporary international situation in marine science. Improvement is needed in a number of areas including the arrangements for national representation, regional coordination arrangements and cooperation with other international organizations. The opportunity exists for the IOC to assume a proactive leadership role in international marine affairs in the twenty-first century (Conclusion 2). The IOC possessesthe experience, structure, linkages and scientific competence to contribute more strongly to the total science effort of UNESCO and to the broader UN system (Conclusion 2.1). The ICSPRO (Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography) Agreement is no longer working effectively and is in urgent need of reactivation or replacement by something more suited to contemporary needs (Conclusion 2.2). The new IOC statutes provide an appropriate legal and organizational framework for the future development of the Commission but they need to be supported by appropriate rules of procedure and agreed administrative structures and practices (Conclusion 2.3). The concept of operation of the Executive Council has proven to be effective and appropriate to the IOC role but it is important, when electing Member States to Council membership, to ensure that the Council retains a high level of specialist oceanographic expertise (Conclusion 2.4). While the IOC is widely recognised for its scientific expertise, there has been a significant tendency in the past for its input not to be sought in the negotiation and implementation of international conventions and agreementswhich require substantial marine expertise (Conclusion 2.5). The regional substructure ofthe Commission is poorly defined and largely ineffective with particular problems associated with its ability to provide a working framework for addressing agreed regional marine priorities (Conclusion 2.6). Many Member States do not have effective national coordination mechanisms and, in general, the linkages between National IOC Committees (where they exist) and National Commissions for UNESCO are weak or non-existent (Conclusion 2.7). The IOC has an excellent opportunity through its chairing and secretariat responsibilities for the new UN ACC-SOCA (United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination - Subcommittee on Oceans and Coastal Areas) to play a much stronger role in the UN handling of marine affairs (Conclusion 2.8). There is substantial scope to build on the IOC-WMO (World Meteorological Organization) JCOMM (Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine 39 . Meteorology) model to enhance IOC collaboration with several other marine-oriented agencies and programmes in the UN system (Conclusion 2.9). The IOC lacks an adequate framework and system for strategic planning and programme evaluation (Conclusion 2.10). The IOC Programme has an enviable record of achievement over many years but has become too unfocussed and thinly spread to be adequately carried out with the resources available. Although the recent restructuring of the Programme has provided a much more appropriate framework for conduct ofthe scientific work ofthe IOC and several individual components of the Programme are now progressing well, the Programme is in need of a much more strategic and focussed leadership if the IOC is to deliver the res’ults which Members expect of it over the coming decade (Conclusion 3). The recent regrouping of the IOC’s scientific and technical programmes into Ocean Science, Operational Observing Systems and Ocean Services has significantly improved the IOC programme structure but the IOC currently lacks a well developed programme planning, management and evaluation framework (Conclusion 3.1). The IOC Ocean Science Programme has served the Commission and IOC Member States extremely well but it is very thinly spread and in need of expert review and refocussing (Conclusion 3.2). IOC has played an effective role in the international planning and coordination of climate research and its joint sponsorship of climate programmes with WMO, UNEP, ICSU and other international organizations has greatly facilitated a cooperative and integrated international approach to climate research (Conclusion 3.3). The IOC has performed a valuable role in participation with other organizations in the study of marine pollution but it needs to avoid duplication and overlap with other international programmes (Conclusion 3.4). The planning and development of GOOS is proceeding very well but the need to support the wide range of planning and interagency coordination activities is placing excessive demands on the GOOS Project Office (Conclusion 3.5). The International Oceanographic Data Exchange (IODE) programme has been very effective in establishing a common framework and standards for exchange of vitally important ocean data. It is performing a continuing valuable function in ensuring that IOC moves with the times in the use of new technologies for data archival and exchange (Conclusion 3.6). The IOC Tsunami Warning (ITSU) programme has been very successful but its extension into regions beyond the Pacific basic will require more resources than can be expected to be available from within the IOC Secretariat. The more direct involvement of potential beneficiary countries will be essential (Conclusion 3.7). The decision to treat capacity building as an integral part of all of IOC’s scientific and technical programmes, and thus as a cross-cutting activity, is appropriate and timely. Because of its importance to so many Member States, IOC’s TEMA. (Training, Education and Mutual Assistance) activities need to be carefully assessedto ensure maximum efficiency and effectiveness in the overall use of resources (Conclusion 3.8). Despite its unquestioned importance to Members, the regional programme of IOC has not been easy to plan or implement effectively. A greatly increased commitment of Members is needed to focus the regional programme on priority issues with expert staff seconded by Members to support the regional effort, with only general coordination from IOC Headquarters (Conclusion 3.9). The IOC, as an organization, and, in particular, its Secretariat, are doing a remarkable job with very limited resources. However, continuation of present arrangements indefinitely is not an option if the Commission is to perform the role Members expect of it. The 40 Commission and its Secretariat are in urgent need of improved management processesand increased resources, both from Regular Budget and external sources (Conclusion 4 ). The IOC Secretariat carries out a vitally important role with great professionalism and dedication but it lacks the resources and management systems and capabilities to adequately meet Members’ expectations of it (Conclusion 4.1). - Although recent reallocation of responsibilities in the Secretariat has provided an improved framework for management of IOC programmes, the staffing situation is sub-critical in most areas with a severe shortage of core professional staff and insufticient continuity and corporate memory to ensure effective and accountable programme management (Conclusion 4.2). The secondment of staff to the Secretariat by Members for periods ranging from a few months to a few years has played a key role in maintaining the viability of several IOC programme activities and has also proved extremely beneficial to Members’ own national marine activities (Conclusion 4.3). The Secretariat lacks a performance culture and effective personnel practices for monitoring staff performance. enhancing staff motivation, recognising high performance and managing under-performance (Conclusion 4.4). The IOC cannot afford to be left behind in the use of emerging technology for internal and external communication, information management, documentation and programme management (Conclusion 4.5). Substantial Secretariat time and financial resources are consumed in the preparation of often excessively detailed and repetitive documentation which is frequently late in its availability to Members and other stakeholders (Conclusion 4.6). Despite substantial goodwill on both sides, the interface between the IOC Secretariat and UNESCO Administration does not work well and is in need of review and streamlining to produce more responsive and efficient administrative support for IOC programme management (Conclusion 4.7). The WESTPAC Oftice is well located and performs a very useful function but is not fully meeting Members’ expectations and needs dynamic leadership to inspire cooperation in the scientific community and raise the profile of IOC in the Western Pacific region (Conclusion 4.8). The IOC has benetited from significant extra-budgetary supplementation of the resources made available from the UNESCO Regular Budget but the overall IOC Programme is severely under-resourced and is in urgent need of increased budgetary support from both the Regular Budget (to maintain the viability of its core functions) and increased contributions to the IOC Trust Fund (to enable urgently needed programmes to proceed at a viable level) (Conclusion 4.9). While available economic analysis suggests that UNESCO and its Members have much to gain from substantially increased investment in the work of the IOC, there is an urgent need for a more rigorous framework for cost-benefit analysis of marine science programmes and for a range of case studies at both the national and international level (Conclusion 4. IO). The IOC’s accounting and budgetary systems and procedures are inadequate to provide the Executive Secretary, governing bodies and Members of the Commission with a sufficiently clear basis for sound decision-making and effective resource management (Conclusion 4.11). - The IOC has benefited from the recent allocation of an “incompressible” budget for its established level of Regular Budget-supported activities but requires a secure longterm resource base compatible with the substantially increased programme needed to meet the expectation of Members (Conclusion 4.12). 41 - . 5.2 The use of the IOC Special Account through which IOC Members and other donors contribute to the IOC Trust Fund (in addition to the provision of seconded staff and in-kind support) has enabled the Secretariat to maintain some support for a wide range of programmes required by Members and has proved highly beneficial to the overall work and effectiveness of the IOC (Conclusion 4.13). The IOC has inadequate experience in, and capabilities for, external fund raising (Conclusion 4.14). While it is not possible, at this stage, to establish the optimum level of overall longterm resourcing of the work of the IOC, it is important that the UNESCO and IOC governing bodies endorse an overall strategic approach to funding of the IOC Programme in line with Members’ expectations over the next 5-l 0 years (Conclusion 4.15). The follow-up action on the 1999-2000 Evaluation of the IOC provides a unique opportunity for UNESCO to draw on its forty years of investment in the development of international oceanography, and the IOC’s own established relationships with the many other marine science-related agencies in the international system, to assist nations to reap the enormous benefits potentially available from marine research and operational oceanography in the twenty-first century (Conclusion 5). Recommendations On the basis of its evaluation of the IOC over the past year and in light of the conclusions summarised above, the Evaluation Team recommends: . That UNESCO and its Member States seize the opportunity to build on their initial investment in the scientific study of the oceans in the second half of the twentieth century to provide the urgently needed global leadership in the development of operational oceanographic services for the benefit of all humanity through the twenty-first century (Recommendation 1). . That UNESCO sponsor and support the progressive development of the IOC as the UN specialised agency for the oceans. formally within the UNESCO framework, but working increasingly closely with the WMO and other partner agencies in the UN system (Recommendation 2). That the UNESCO Director General, Executive Board and General Conference endorse a new and more proactive leadership role for the IOC in international marine science and services based on a substantially strengthened commitment to the role of the Commission as a central element of the science mission of UNESCO (Recommendation 2.1). That UNESCO and the IOC, in partnership with the other ICSPRO (Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography) agencies,review the appropriateness of the ICSPRO mechanism with a view to its rejuvenation or replacement by some new mechanism more suited to contemporary needs (Recommendation 2.2). That new IOC rules of procedure be developed as a matter of urgency to facilitate and support the operation of the new statutes (Recommendation 2.3). That Member States nominating for membership of the IOC Executive Council be encouraged to identify individuals with strong personal marine science credentials as their representatives on the Council (Recommendation 2.4). That the IOC play a more effective role in global and regional marine conventions and agreements that impose obligations on Member States (Recommendation 2.5). 42 That the IOC governing bodies undertake a comprehensive review of the regional structure of the Commission with a view to its rationalisation and sharper focussing on regional needs and priorities (Recommendation 2.6). That Member States, who have not done so, be urged to establish formal national oceanographic committees (National Committees for the IOC) as focal points for IOC within their countries; and that these be established in close collaboration with National Commissions for UNESCO so as to ensure effective linkages between the National Commissions and all those institutions and agencies with an interest in the marine environment (Recommendation 2.7). That the present IOC role as Chair and Secretariat of the UN ACC-SOCA (United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination - Subcommittee on Oceans and Coastal Areas) be given high priority and that the IOC communities within Member States be encouraged to develop complementary linkages into the UNCSD (UN Commission for Sustainable Development) process (Recommendation 2.8). That the Executive Secretary investigate the scope for stronger and more effective ties with IMO (International Maritime Organization), UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) and the FA0 (Food and Agriculture Organization), based on the IOC-WMO (World Meteorological Organization) JCOMM (Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology) model, with a view to improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the IOC role (Recommendation 2.9). That the IOC governing bodies and Executive Secretary give priority to the development and implementation of an appropriate system of strategic planning and programme evaluation compatible with the needs and working methods of the Commission (Recommendation 2.10). That the IOC governing bodies and Executive Secretary review and revitalise the IOC programme structure and its planning, priority setting and management systems in line with its new statutes and based on modernised and streamlined arrangements for consultation and communication within the IOC Secretariat and Regional Offices (Recommendation 3). That the IOC give very high priority to further review of its scientific and technical programme structure and management with a view to implementing a more strategic and systematic approach to program planning, management and evaluation (Recommendation 3.1). That the IOC prepare an overall strategic plan for the Commission’s future role in ocean sciences with particular emphasis on ensuring that the plan is realistic and focussed on the identified priorities of Member States (Recommendation 3.2). That the IOC maintain and strengthen its role, in partnership with other relevant international organizations, in sponsoring international climate research and, particularly, in involving the relevant science agencies of its Member States in the coordinated research effort (Recommendation 3.3). That GIPME (Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment) technical design ensure that the future role of the IOC is compatible with other international mechanisms for dealing with marine pollution whilst also preserving a clear and appropriate role for the IOC (Recommendation 3.4). That the GOOS Steering Committee (GSC) and GOOS Project Office (GPO) continue to explore ways of reducing the complexity of the GOOS organization and the number of GOOS-associated meetings (Recommendation 3.5). That the IOC continue to strongly support the work of IODE (International Oceanographic Data Exchange) through the Joint Technical Commission on Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM) and in other ways and encourage - 43 . its efforts to establish widely accepted global standards for marine data (Recommendation 3.6). That the International Tsunami Warning (ITSU) programme be examined to establish the extent of the continuing role needed of the IOC with Member States of regions desiring support. being encouraged to undertake more direct responsibility for resourcing of the programme (Recommendation 3.7). That the IOC efforts in Training, Education and Mutual Assistance (TEMA) be strongly endorsed and strengthened and that both donor and recipient Members be encouraged to give priority to TEMA activities as part of their participation in IOC scientific and technical programmes (Recommendation 3.8). That the IOC governing bodies and Regional Sub-Commissions and Committees give priority to redefining the IOC approach to regional programme planning and implementation with a view to ensuring that IOC programmes focus clearly on regional priorities (Recommendation 3.9). That UNESCO and IOC Member States be urged to strengthen their contribution to the work of the IOC through enhanced national marine programmes and increased financial and other support for the international planning and implementation of marine activities, and especially through extrabudgetary funding and the secondment of expert staff to participate in the international planning and management processes in both the IOC Secretariat and the Regional Offices (Recommendation 4). That the Executive Secretary vigorously pursue his efforts to strengthen and streamline the overall working of the Secretariat by programme implementation of more efficient management support arrangements and improved work practices (Recommendation 4.1). That urgent steps be taken to increase the core professional staffing of the Secretariat with a target of increasing the permanent professional posts in the Paris headquarters from nine to eighteen within two years (Recommendation 4.2). That Member States be strongly encouraged to consider secondment of professional staff to the IOC Secretariat on both a short and extended term basis, consulting with the Executive Secretary in respect of the scientific and management skills of secondees who might contribute most effectively to the achievement of both the individual Member’s objectives and those of the IOC as a whole (Recommendation 4.3). That the Executive Secretary introduce an appropriate performance management system into the Secretariat and give increased priority to measures aimed at enhancing staff motivation and recognising outstanding achievement (Recommendation 4.4). That the Secretariat progressively modernise and streamline its internal and external communication and information management systems and introduce appropriate management methodologies consistently across programme areas (Recommendation 4.5). That a review of IOC documentation preparation and distribution be undertaken to see if simpler, more timely and less time-consuming and less costly systems can be put in place (Recommendation 4.6). That the Executive Secretary and his counterpart in UNESCO Administration be invited to explore ways of improving the efficiency and responsiveness of UNESCO administrative support for the IOC (Recommendation 4.7). That the WESTPAC Office be maintained in Bangkok with significant internal reorganisation and improved arrangements for communication and coordination within the region and enhanced planning and devolution of resource management from IOC headquarters (Recommendation 4.8). 44 - . 5.3 That the Executive Secretary be invited to prepare a strategic resourcing plan for the highest priority work of the Commission over the next decade as a framework for increased support from the UNESCO Regular Budget and enhancedcontribution from extra-budgetary sources (Recommendation 4.9). That the IOC should take a lead in encouraging and assisting Members and their marine institutions in carrying out cost-benefit analysis of a range of marine science and technology projects to assist in decision-making on IOC’Programme funding at both the national and international levels (Recommendation 4.10). That, as a matter of urgency, UNESCO assist the IOC Secretariat in the implementation of modern cost accounting and financial management systems and procedures to enable the IOC Executive Secretary, governing bodies and Members to be provided with essential programme-based financial information for decisionmaking (Recommendation 4.11). That UNESCO provide an increased fixed percentage of its Regular Budget for support of the operation of the IOC (Recommendation 4.12). That IOC Member States and partner organizations be encouraged to contribute on a regular basis, and at an increased level, to the IOC Trust Fund to complement and reinforce the increased core capabilities resulting from stronger Regular Budget support of the IOC (Recommendation 4.13). - _ That the IOC seek external assistancein strengthening its capabilities for raising funds from new sources to supplement the resources available from the UNESCO Regular Budget and the IOC Special Account (Recommendation 4.14). That the UNESCO and IOC governing bodies and Members endorse and support the progressive strengthening of the IOC and international marine science programmes through increased resourcing from both Regular Budget and extra-budgetary sources in the light of the IOC strategic resource plan (Recommendation 4.15). That IOC’s partner agencies and programmes within and outside the UN system be invited to join in the new and more integrated approach to exploiting the opportunities which recent developments in marine science and technology offer to the global community in the twenty-first century (Recommendation 5). Lessons Learned The Evaluation Team believes that some useful general lessons may be learned from this Evaluation and from the work of the IOC as follows: . Many in the international marine research community are not particularly aware of the role, or even the existence, of the IOC and it is clear that much stronger efforts are needed to raise the awareness of UNESCO science programmes, even within the relevant expert scientific communities. . Questionnaires seeking national input on programme performance need to be cast in clear and simple terms and it should not be assumed that all respondents will have a high level of familiarity with the details of the programmes being evaluated. . There is a large reservoir of insight and wisdom on ways of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the IOC resident in the intergovernmental marine science community and in the IOC Secretariat and a great willingness in IOC’s partner organizations and the marine community to help the Commission in carrying out its mandate. . UNESCO and the IOC have much to gain by drawing on the experience and goodwill of other international marine-oriented agencies to build the Commission into an effective specialised agency for the oceans over the next decade. . Although the resources presently available to the IOC appear grossly inadequate for the challenges it has before it. there are substantial opportunities and scope, within the 45 management flexibility of UNESCO and the national oceanographic institutions of many Member States, to strengthen the Commission to carry out the responsibilities which its Members expect of it, with large net benefit to all. Finally, the Evaluation Team learned that evaluation of an organization as complex and wideranging as the IOC is a daunting task. The Team regrets that limitations of time and resources constrained it to an inevitably broad-brush treatment of many aspects of the operation of the IOC where more time and greater in-depth knowledge might -have enabled more insightful and focussed recommendations to be provided. 47 APPENDIX A LIST OF ACRONYMS ACC ACC-SOCA ACOPS ADG/ADM ADG/COR/ENV ADG/IOC ADG/SC ARGO ASFA ASFIS BSRC ccc0 CGOM C-GOOS CICAR CIM CLIVAR COBSEA COP COST CPPS CSD DAIM DBCP DNA EEZ ENS0 ESCAP ETDB EU EuroGOOS FA0 FCCC FGGE G30S GAPA GATE GCOS GCRMN GEBCO GEEP GEF GEMIM GEMS1 GEOHAB GESAG GESAMP Administrative Committee on Co-ordination (UN) ACC Subcommittee on Oceans and Coastal Areas Advisory Committee on Protection of the Sea Assistant Director-General for Administration Assistant Director-General for Coordination of Environmental Programmes Assistant Director-General IOC Assistant Director-General for Natural Sciences Array for Real-time Geostrophic Oceanography (CLIVAR-GODAE) Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System Black Sea Regional Committee Committee on Climate Changes and the Oceans IOC Consultative Group on Ocean Mapping Coastal GOOS Cooperative Investigation of the Caribbean and Adjacent Reg,ions Cooperative Investigation in the Mediterranean Climate Variability and Predictability (WCRP) Coordinating Body on the Seas of East Asia (UNEP) Conference of the Parties (to the UN FCCC) European Co-operation in the Field of Scientific and Techniccal Research Permanent Commission for the South Pacific Commission on Sustainable Development (UN) Data Availability Index Maps Data Buoy Co-operation Panel (WMO-IOC) Designated National Agency Exclusive Economic Zone El-NiAo-Southern Oscillation Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN) Expert Tsunami Data Base European Union European GOOS Food and Agriculture Organization (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change (UN) First GARP Global Experiment Global Observing Systems (GCOS-GOOS-GTOS) Geophysical Atlases of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (IOC) CARP Atlantic Tropical Experiment Global Climate Observing System Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (IOC-IHO) Group of Experts on Effects of Pollutants Global Environment Facility (World Bank-UNEP-UNDP) Group of Experts on Marine Information Management (IODE) Group of Experts on Methods, Standards and Intercalibration Global Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms GIPME Expert Scientific Advisory Group Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environment Protection (IMO-FAO-UNESCO/IOC-WMO-WHO-IAEA-UN-UNEP) 48 GETADE GFCM GIPME GLOBEC GLODIR GLOSS GODAE GODAR GOOS GOSSP GPA GPO GPS GSC GTOS GTS GTSPP HAB HOT0 . IAEA IASC IBCM IBP ICAM ICCOPS ICG-ITSU ICITA ICES ICRI ICSEM ICSPRO ICSU ICZM IDOE IDNDR IFREMER IGBP IGCP I-GOOS IGOS IGOSS IGU IHO IHP IMCO IMO IOC Group of Experts on Technical Aspects of Data Exchange (IODE) General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean (FAO) Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment Global Ocean Ecosystems Dynamics (SCOR-IOC) Global Directory of Marine (and Freshwater) Professionals Global Sea-level Observing System Global Ocean Data Assimilation Experiment (GOOS) Global Oceanographic Data Archaeology and Resource Project Global Ocean Observing System (IOC-WMO-UNEP-ICSU) Global Observing Systems Space Panel (G30S) Global Programme of Action (for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities) (UNEP) GOOS Project Office (formerly GSO) Global Positioning System GOOS Steering Committee Global Terrestrial Observing System (FAO-UNEP-UNESCO-WMO-ICSU) Global Telecommunication System (WWW) Global Temperature-Salinity Pilot Project/Profile Programme Harmful Algal Blooms Health of the Oceans (module of GOOS) International Atomic Energy Agency International Arctic Science Committee (Oslo, Norway) International Bathymetric Chart for the Mediterranean IGOOS Product Bulletin Integrated Coastal Area Management International Centre for Coastal and Ocean Policy Studies International Coordination Group for the Tsunami Warning System for the Pacific International Cooperative Investigation of the Tropic Atlantic International Council for the Exploration of the Sea International Coral Reef Initiative International Commission for the Scientific Exploration of the Mediterranean Sea Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography International Council for Science Integrated Coastal Zone Management International Decade of Ocean Exploration International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction French Institute of Research and Exploitation of the Sea International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (ICSU) International Geological Correlation Programme (UNESCO) Intergovernmental Panel for GOOS (IOC-WMO-UNEP) Integrated Global Observing Strategy (GCOS-GOOS-GTOS+CEOS) Integrated Global Ocean Services System International Geographical Union International Hydrographic Organization International Hydrological Programme (UNESCO) International Maritime Consultative Organization International Maritime Organization Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO) 49 10c/0cs IOC/OOS IOC/OSC IOC-VAP IOCARIBE IOCEA IOCINCWIO IOCINDIO 10cs0c IODE IOSLON IPCC ITIC ITSU IUCN IUGG IWCO IYO JCOMM JDIMP JGOFS JODC LEPOR LME LMR-GOOS LOICZ MAB MAP MAPMOPP MARPOLMON MEA MedGOOS MEDI MEDPOL MEL MEMAC MESL MIM MOST MPU NATO NEAR-GOOS NGO NOAA NODC ODAS ODINAFRICA IOC Ocean Services IOC Operational Observing Systems IOC Ocean Science IOC Voluntary Assistance Programme IOC Sub-commission for the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions IOC Regional Committee for the Central Eastern Atlantic IOC Regional Committee for the Co-operative Investigation in the North and Central Western Indian Ocean IOC Regional Committee for the Central Indian Ocean IOC Regional Committee for the Southern Ocean International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IOC) Indian Ocean Sea Level Observing Network Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (WMO-UNEP) International Tsunami Information Centre International Co-ordination Group for the Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific (IOC) International Union for the Conservation of Nature (and Natural Resources) International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (ICSU) Independent World Commission on the Oceans International Year of the Ocean (1998) Joint IOC-WMO Technical Commission for Oceanography and Marine Meteorology Joint G30S Data and Information Management Panel Joint Global Ocean Flux Study (IGBP) Japan Oceanographic Data Centre Long-term and Expanded Programme of Ocean Exploration and Research Large Marine Ecosystems Living Marine Resources module of GOOS Land-Ocean Interaction in the Coastal Zone (IGBP) Man and the Biosphere Programme (UNESCO) Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP) Marine Pollution Monitoring Pilot Project Marine Pollution Monitoring System Working Group on Marine Environmental Assessments (GESAMP) Mediterranean regional GOOS Marine Environmental Data Information Referral Service Co-ordinated Mediterranean Pollution Monitoring and Research Programme (UNEP) Marine Environment Laboratory (IAEA) Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre, Bahrain Marine Environment Studies Laboratory (IAEA-MEL) Marine Information Management (IODE) Management of Social Transformations Programme (UNESCO) Marine Pollution Research and Monitoring Unit (IOC) North Atlantic Treaty Organization North-East Asian Regional GOOS Non-Governmental Organization National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (USA) National Oceanographic Data Centre (IODE) Ocean Data Acquisition Systems Oceanographic Data and Information Network for Africa 50 ODINEA OOPC OOSDP OPC OSLR OSNLR PACSICOM POEM PRIM0 PSMSL RNODC ROPME SAREC SBSTA SCOR SEAPOL SIDS SOOP SOOPIP . SOPAC STAR TAO TEMA TOGA UKMO UNCED UNCLOS UNCSD UNEP UNGA UNIDO UOP vos WCP WCRP WDC WESTPAC WIPO WMO WOA WOCE WOD www www XBT Oceanographic Data and Information Network for Eastern Africa Ocean Observations Panel for Climate Ocean Observing System Development Panel (replaced by OOPC) ’ Ocean Processes and Climate (IOC) Ocean Science in Relation to Living Resources (IOC) Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Living Resources (IOC) Pan-African Conference on Sustainable Integrated Coastal Management (Maputo, Mozambique, 18-25 July 1998) Physical Oceanography of the Eastern Mediterranean Programme de Recherche International en Mediterranee Occidentale Permanent Service for Mean Sea-Level (UK) Responsible National Oceanographic Data Centre (IODE) Regional Organization for the-Protection of the Marine Environment Swedish Agency for Research Co-operation with Developing Countries Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (UN/FCCC) Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (ICSU) Southeast Asian Programme on the Law of the Sea Small Island Developing States Ship-of-Opportunity Programme SOOP Implementation Panel (IGOSS) South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission Joint CCOPSOPAC-IOC Working Group on South Pacific Tectonic and Resources Tropical Atmosphere Ocean Array Training, Education and Mutual Assistance (IOC) Tropical Ocean and Global Atmosphere (WCRP) United Kingdom Meteorological Office United Nations United National Conference on Environment and Development (Brazil, 1992) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Montego Bay, 1982) United Nations Commission for Sustainable Development United National Environment Programme (UN) United Nations General Assembly United Nations Industrial Development Organization Upper Ocean Panel (CLIVAR) Voluntary Observing Ship (WMO) World Climate Programme World Climate Research Programme (WMO, IOC, ICSU) World Data Centre (ICSU) IOC Sub-commission for the Western Pacific World Intellectual Property Organization (crr\J) World Meteorological Organization World Ocean Atlas World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WCRP) World Ocean Database World Wide Web (Internet) World Weather Watch (WMO) Expendable Bathythermograph 51 APPENDIX A BRIEF HISTORY B OF THE IOC - First Intergovernmental Conference on Oceans formulated the recommendations for an intergovernmental oceanographic body to be established within UNESCO to promote concerted actions of Member States in the field of oceanographic research. July 1960, Copenhagen, Denmark 1960 - Eleventh Session of UNESCO’s General Conference adopted the recommendations of the First Intergovernmental Conference on Oceans and approved the statutes of the IOC. The Office of Oceanography was set up within UNESCO. November-December 1961-65 - IOC provided co-ordination arrangements and assisted in the publication of the results of the 1959-65 International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIOE) in the form of five comprehensive atlases. October 1961 - First Session of the IOC Assembly decided on the organizational structure, provisional rules of procedure and the general objectives of the Commission and established its subsidiary bodies. The Chairman and two Vice-Chairmen were elected and a Consultative Council was established. There were 40 Member States. 1961 - A Working Group on Data Exchange was established and the basis for the International Oceanographic Data Exchange Programme (IODE) was put in place. (In 1973, the Working Group was renamed as the Working Committee on IODE and, in 1987, it was named the Committee on International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange, in recognition ofthe importance of marine information for different areas of application. The acronym was retained.) 1962 - IOC Bureau decided to hold the Bruun Memorial Lectures at each IOC Session in recognition of the input to the development of the IOC of Professor Anton Bruun, who passed away on 13 December 196 1. These lectures are focussed on the results of important scientific engagements of IOC during the preceding 2-year period. 1962-65 - IOC. with the assistance of SCOR (Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research) which became an IOC scientific consultative body, prepared and published “Perspectives in Oceanography, 1969” which contained a scientific framework for the comprehensive study of the world’s oceans. 1963 - International Marine Science (IMS) Newsletter was first published by UNESCO. (It was suspended in February 1970 and revived in 1972 with the collaboration of the UN (United Nations), FA0 (Food and Agriculture Organization), IMO (International Maritime Organization) and WMO (World Meteorological Organization) in English. By 1986, IMS was produced in six languages and distributed in more than 10,000 copies worldwide free of charge. In 1996, due to UNESCO restructuring, the publication was stopped.) April 1963-64 - International Co-operative Investigation of the Tropical Atlantic (ICITA) involved an oceanographic multi-ship survey of the Tropical Atlantic Ocean. Observations included direct current measurements as well as meteorological, oceanographic, biological, bathymetric and geophysical observations. The results were published by the IOC in two volumes. June 1964 - The IOC Assembly at its Third Session recognized the need for a special programme which would co-ordinate capacity building activities and identify priorities for IOC in providing training, education and mutual assistance to developing countries. 52 1964-67 - Working groups on Mutual Assistance in Training and Education in Oceanography were created. They were replaced later by the Committee for TEMA (Training, Education and Mutual Assistance). June 1964, Paris, France - Third Session of the IOC Assembly adopted changes to the IOC statutes which were approved by the Thirteenth Session of the UNESCO General Conference the same year. 1965 - An IOC Working Group on Marine Pollution was established. (In 1969 it was superseded by the Joint IMCO (International Maritime Consultative Organization)-FAO-UNESCOWMO-WHO-IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency)-UN-UNEP Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution (GESAMP).) 1965 - Tsunami Warning Programme in the Pacific started with the establishment of the International Co-ordination Group for the Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific (ICG/ITSU), with the purpose of providing or improving all aspects of tsunami mitigation including hazard assessment,warnings, preparedness and research. The International Tsunami Information Centre (ITIC) was organized. (The most recent (Seventeenth) Session of the ICG/ITSU took place in 1999.) 1965 - The first edition of the “Manual on International Oceanographic Data Exchange” was published. (The Manual was regularly revised and the most recent edition was published jointly with the ICSU Panel on WDC in 1991.) 1965-77 - Co-operative Study ofthe Kuroshio and Adjacent Regions included studies ofphysical, chemical and biological oceanographic conditions and processes, and included fisheries oceanography and meteorological observations. (The results were discussed at a series of symposia and the proceedings were published under the titles “The Kuroshio”, “The Kuroshio II” and “The Kuroshio III”.) recognizing the need for greater knowledge of the oceans and for the utilization of their resources, requested proposals for ensuring effective arrangements for an expanded programme of international co-operation. (The report “International Ocean Affairs” was produced in the northern summer of 1967.) December 1966 - The UN General Assembly (UNGA), 1967 - A permanent “Working Committee for an Integrated Global Ocean Station System” was established within the IOC. (It was replaced in 1977 by the joint IOC-WMO Working Committee for IGOSS which had its first session in 1978. In 198 1, in a change in the name of the Committee, the word “Station” was changed to “Services”.) 1967-76 - Co-operative Investigation of the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions (CICAR) was carried out as an area-oriented research programme with a strong capacity-building component. (Implementation of the programme helped create national marine science structures in the region.) 1967, 1975 and 1977 - The IOC SOC (IOC Regional Committee for the Southern Ocean), IOCARIBE (IOC Sub-Commission for the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions) and WESTPAC (IOC Sub-Commission for the Western Pacific) regional bodies were established respectively, thus creating the basis for regionalization of the IOC programme activities. (Today there are seven such regional bodies.) 53 December 1968 - UNGA endorsed the concept of a long-term and expanded programme of oceanographic research and welcomed the idea of an International Decade of Ocean Exploration (IDOE). 1969-82 - Co-operative Investigation in the Mediterranean (CIM) was implemented jointly with ICSEM (International Commission for the Scientific Exploration of the Mediterranean Sea) and the General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean (GFCM) ofFA0. Some successwas attained in marine pollution research, in the preparation of a new International Bathymetric Chart of the Mediterranean (IBCM) and in data collection, processing and exchange. 1969 - The Inter-secretariat Committee on Scientific Programmes Relating to Oceanography (ICSPRO) was established with the objective of contributing to the development of effective forms of co-operation among organizations of the UN family concerned with oceanic programmes. The Committee consisted of the Executive Heads of the UN, FAO, UNESCO, WMO and IMO. September 1969 - IOC adopted the “General Plan and Implementation Programme for IGOSS for Phase I” to deal with the temperature and salinity data collection from the upper layer of the ocean. September 1969 - Sixth Session of the IOC Assembly extended the number of Vice-Chairmen to four persons, re-formulated the functions of the Commission and replaced the Consultative Council by the Executive Council. It approved the Long-term and Expanded Programme of Ocean Exploration and Research (LEPOR). 1971 - The Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System (ASFIS) was set up jointly with FAO. The publication of ASFA (Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts) started from July 1971. 1971-80 - International Decade of Ocean Exploration (IDOE) was implemented,, consisting of national oceanographic activities of significant size and scope in which the participation of scientists from other nations was actively sought. November 1971 - Seventh Session of IOC Assembly established the Global Investigations of Pollution in the Marine Environment (GIPME) programme. (In 1972, the International Coordination Group was created for promoting and monitoring its implementation. It was replaced by a Working Committee for GIPME in 1975. GIPME investigations focus not only on the coastal zone and shelf seas but also deal, where appropriate, with the open ocean. The programme assessesthe presence of contaminants and their effects on human health, marine ecosystems and marine resources, and amenities, both living and non-living. GIPME is sponsored by IOC, UNEP and IMO and IAEA is a partner through its Marine Environment Laboratory.) 1972 - BATHY and TESAC Pilot Project of IGOSS was launched to deal with the operational collection and exchange of temperature and salinity data. (It became fully operational in 1975.) 1972 - UNESCO-IMCO (subsequently IMO) co-sponsored Preparatory Conference of Governmental Experts to formulate a draft Convention on the Legal Status of Ocean Data Acquisition Systems (ODAS). (The problem of the legal status of ODAS, however, remains unsolved.) 1972 - Ocean Mapping Programme was established in response to the decisions of UNGA. 54 1972 - UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden, requested IOC to organize marine pollution monitoring jointly with WMO. (The Marine Pollution Monitoring Pilot Project (MAPMOPP) was developed and approved by IOC, WMO and UNEP in 1973.) October 1972 - Office of Oceanography was re-organized into the IOC Secretariat and the UNESCO Office of Oceanography (later re-named the UNESCO Division of Marine Sciences), as separate entities with the Secretary of the IOC reporting directly to the Assistant Director General for Science (ADG-SC). 1973 - IOC joined IHO (International Hydrographic Organization) in managing the General Bathymetric Chart of the Ocean (GEBCO). The joint IOC-IHO Guiding Committee for GEBCO was established and its first meeting took place in 1974. 1974-78 - The GARP Atlantic Tropical Experiment (GATE) was implemented jointly with WMO and ICSU. It contained an oceanographic component, with the focus on the study of the interaction between the ocean and atmosphere, and of the processes of energy transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere and within the atmosphere in various scales of motion. A Synoptic Atlas, composed of 3 volumes was published to present the oceanographic data collected during GATE. 1975 - Geological/Geophysical Atlas of the Indian Ocean was published. (It was followed by one on the Atlantic Ocean, published in 1989.) 1976 - A Comprehensive Plan for the Global Investigation of Pollution in the Marine Environment (GIPME) was adopted. It provided an international scientific framework and helped to focus Member States’ efforts on the establishment ofa sound scientific basis for the assessment and regulation of the marine pollution problem. (The plan was re-evaluated in 1984. GIPME is presently going through a re-evaluation process by taking into account the overall scientific activities within IOC, the new perspectives of damage and threats to the marine environment, its resources and amenities, and scientific advances made in the last two decades.) 1976 - The First Five Year IGOSS General Plan and Implementation Programme was drafted. (Subsequently, it was been regularly updated, with the most recent one issued in 1996 for 19962003 .) July 1977 - Second Session of the Working Committee for Training, Education and Mutual Assistance (TEMA) recommended that TEMA activities become a compulsory component of all IOC programmes. November 1977 - Tenth Session of the IOC Assembly adopted the creation of the Voluntary Assistance Programme (IOC-VAP). 1978-80 - The First GARP Global Experiment (FGGE) was held. This experiment provided an opportunity for oceanographers to study ocean processes originating from atmospheric forcing. 1978-90 - Development of the GF-3 format and publication of six volumes of the GF-3 Manual. RNODC for GF-3 was established at the ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) Headquarters. 1979 - The First Edition of the Maritime Environmental Data Information Referral System (MEDI) Catalogue was published. (The last edition in hard copy form was published in 1993. Today the Catalogue is available electronically.) 55 October 1979 - Committee on Climate Change and the Oceans (CCCO) was formed jointly with SCOR to plan the ocean component of the World Climate Research Programme (.WCRP) (eg TOGA and WOCE), as well as other (non-WCRP) issues of climate change involving the ocean. IOC provided the Secretariat for CCCO. (The Committee was terminated in 1991. The CCCO’s last product was a document titled “Oceanic Interdecadal Climate Variability”.) Mid-1980s - Oceanographic studies in the Mediterranean contributed to Alpex. Implementation of POEM (Physical Oceanography of the Eastern Mediterranean) which encompassed not only physical but also biological and chemical oceanography and PRIM0 (Programme de Recherche International en Mediterranee Occidentale) which focussed on the dynamics of water masses. November 1982 - Ocean Science and Living Resources Programme (OSLR) was established by the Twelfth Session of the IOC Assembly. (OSLR now includes programme elements focussed on coral reefs (Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) and the GCRMN South Asia Node). Harmful Algal Blooms (HAB) and the Living Marine Resources (LMR) module of GOOS. In 2000, an expert panel will review OSLR in order to recommend how the programme can maintain and increase its relevance to the living marine resource research, mana.gement and user communities). At the same session, the Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Livin,g Resources (OSNLR) programme was established to provide scientific and technical advice in the area of seafloor minerals studies and exploitation.) 1984 - Fifth edition of GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans) was published through the joint effort of IOC and IHO. December 1984 - Ocean Carbon Dioxide (COz) Panel was established by CCCO. (It was converted into the JGOFS-IOC panel in September 1988 to oversee the task of obtaining a high quality coherent global dataset on ocean COz. In July 1994, a document was produced - “CO, and the Ocean: A Review of the State of Knowledge” The Panel completed its task in 1999 and is being reconstituted jointly with SCOR in light of today’s new CO, issues. The stewardship for the Panel was provided by IOC.) 1985 - The Global Sea-level Observing System (GLOSS) was instituted as a programme for the provision of high quality sea-level information for international and regional research activities, as well as for the support of practical applications at the regional and national level. January 1985-December 1994 - TOGA (Tropical Ocean Global Atmosphere) was implemented. (A tropical Pacific ocean observing array of moored buoys was produced that provided real-time surface and sub-surface data for the development of ocean-atmosphere coupled models for predicting the El Nina cycle. IOC and WMO sponsored a TOGA intergovernmental Board that reviewed the programme from a government perspective. IOC under COOS continues to provide stewardship for the panels maintaining and expanding the Tropical Ocean Atmosphere (TOA) array of moored buoys in the world’s oceans.) 1986 - Nineteenth Session of the IOC Executive Council accepted the WMO invitation to cosponsor the Drifting Buoy Co-operation panel (DBCP). 1987 - First product of the International Bathymetric Chart of the Mediterranean Sea (IBCM) project was printed. It marked the beginning of the IBCM geological./geophysical series publication which includes maps of gravity anomaly and seismicity, plio-quatemary sediment thickness and sediment maps. (The last map was published in 1996 and contains magnetic anomaly data.) 56 1987 - The twenty-fourth Session of the UNESCO General Conference provided the IOC with functional autonomy within UNESCO. 1988 - The Global Temperature-Salinity Pilot Project (GSTPP) was launched in co-operation with WOCE in an attempt to bring operational and non-operational data flows closer. 1988 - IOC Executive Council established an IOC Group of Experts on’GLOSS. (This Group produced the first Implementation Plan for GLOSS which was published in 1990. A new version of the Plan which defines the programme into the next century was adopted by the IOC Assembly in 1997.) 1988 - A workshop on education and training required towards addressing marine science and technology for the years beyond 2000 was organized by UNESCO with IOC participation. (The results of the discussions were published by UNESCO as “Year 2000 Challenges for Marine Science Training and Education Worldwide”.) 1989 - The first edition of the Tsunami Master Plan which is designed as a long-term guide for improvement of the tsunami warning system was published. (It provides a description of the current status of the Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific with an identification of its limitations and presents the views on corresponding directions for progress. The second edition of the Master Plan was published in 1999.) 1990-97 - The field phase of WOCE (World Ocean Circulation Experiment) was implemented. The most comprehensive and accurate datasets were produced making possible new scientific insights into the role of the ocean in climate. IOC sponsored an Intergovernmental WOCE Board and provided stewardship. (Analysis, interpretation, modelling and syntheses efforts will continue through until 2002.) July 1990 - The First Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in which IOC played a role of expert reviewer was published. (The IPCC’s Second Assessment Report was published in 1996 and the Third Assessment Report is now under preparation.) September 1990 - The first meeting of the Ocean Observing System Development Panel (OOSDP) established by CCC0 and the Joint Scientific Committee (JSC) for the WCRP (World Climate Research Programme) was held. (The OOSDP final report titled “The Scientific Design of the Common Module of GOOS and GCOS: An Ocean Observing System for Climate” was published in 1995.) October-November 1990 - IOC co-sponsored the Second World Climate Conference which produced a Ministerial Declaration aimed at reversing the damage being done to the earth’s climate that can be attributed to human activity. The Second World Climate Conference identified the need to establish a Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) of physical, chemical and biological measurements as a major component of the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS). November 1990 - The OceanPC project of IODE was approved for implementation. (The first phase of its implementation culminated with the publication in 1995 of the OceanPC Manual and common software for management and international exchange of oceanographic data.) 57 1991 - Publication of the IGOSS Products Bulletin (hard-copy version) was started. (The publication was replaced by an electronic version in 1994.) March 1991 - Sixteenth Session of the IOC Assembly approved IOC co-sponsorship of the WCRP. At the same session, .a resolution recognizing the need to undertake the development of GOOS and establish a GOOS Support Office within the IOC Secretariat was adopted. July 1991 - First in the series of international meetings of Scientific and Technical Experts on Climate Change and the Ocean was held 19-2 1 July. (The meetings led to the publication in the IOC Technical Series of “The Ocean and Climate: A Guide to Present Needs” and “A Review of the State of Knowledge” of the problem of the ocean and CO,.) 1992 - The decision was taken to have the memorial lectures dedicated to the memory of Professor R Revelle, one of IOC’s founders, who passed away in 1991. (The first lecture entitled “Roger Revelle and his Contribution to International Ocean Science” was given at the Twentyfifth Session of the IOC Executive Council. The objective of the lectures is to give a foresight on the future development of ocean and coastal area research and management.) Ocean Climate Data Workshop brought together scientists and data managers to identify opportunities for improving data management in support of ocean climate research. February 1992 - IOC-CEC-ICES-WMO-ICSU March 1992 -The IOC Committee for GOOS was established to serve as the intergovernmental forum for promoting GOOS. (Later this Committee became known as I-GOOS. A GOOS Technical and Scientific Advisory Panel was also established to advise on all scientific and technical aspects of GOOS and undertake negotiations with ICSU and SCOR. and other appropriate scientific and technical bodies to facilitate its establishment. This Panel later became known as J-COOS.) June 1992 - The UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Its recommendations in Agenda 21 featured GOOS prominently. The Conference recognized the leading role of IOC in research and systematic observations in relation to “protection of the oceans, all kinds of seas,including enclosed and semi-enclosed seas and coastal areas, and the protection, rational and development of their living resources” and related capacity building. (The ACC Sub-Committee on Oceans and Coastal Areas (ACC-SOCA) was subsequently established and the IOC took the responsibility for providing secretariat support. In 1999, the Executive Secretary IOC became Chairperson of the ACC-SOCA.) 1993 - The IODE Data Management Policy for Global Ocean Programmes was adopted at the Seventeenth Session of the IOC Assembly. The Global Oceanographic Data Archeology and Rescue Project (GODAR) was approved for implementation. (The results of the first phase of the project were summed up at the International GODAR Review Conference in July 1999, Washington. USA.) February-March March 1993 - The CLIVAR programme was established by the Joint Scientific Committee (JSC) for the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP). (In December 1998, IOC hosted the International Conference on CLIVAR. The Conference statement was produced explaining the CLIVAR objectives and inviting Member States to indicate their interest and intentions for participating.) 58 November 1994 - The Second International Conference on Oceanography was held in Lisbon, Portugal. The Conference issued two symbolic documents “The Oceans - A Shared Vision” (based on the scientific experts) and a “Declaration” (endorsed by the governmental experts) which expressed the agreement on basic concerns and on the implications for future work vis-avis research on oceans and coastal areas. 1994 - The first book ‘Coastal Zone Space” by E.D. Goldberg was published in a new series of IOC publications entitled “IOC Ocean Forum”. The publication addressed “critical uncertainties” identified by UNCED. (The most recent book in the series has been published in 2000 dealing with the El Nifio phenomenon.) 1994 - A CD-ROM version of the GEBCO,Digital Atlas was published and widely circulated. (An updated version of this CD-ROM appeared in 1997 and the next edition is planned for 200 1.) 1995 - IOC Homepage was developed on the WWW (World Wide Web) server. 1995 - The International Conference on Coastal Change in Bordeaux, France, summed up the progress in the OSNLR programme. 1995 - The Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) was created jointly with UNEP and the World Conservation Union in response to global degradation of coral reef ecosystems. (The GCRMN improves conservation and management of reefs by providing data on status and trends of reef ecosystems, and increases the capacities of individuals, organizations and governments to participate in reef monitoring and assessment, and to disseminate the resulting information.) 1995 (1998-1999) - The results of the first phase of the IODE/GODAR project were published and circulated to users in the form of Technical Reports and sets of CD-ROMs. (They have been included in World Ocean Atlas ‘94 and World Ocean Database ‘98 and World Ocean Atlas ‘98.) March 1995 - TEMA Strategy ad hoc Meeting addressed the implications of UNCED and UNCLOS for the capacity building/TEMA programme and discussed strategy. (As a follow-up, a Group of Experts for TEMA capacity building was established which proposed in 1996 the TEMA Action Plan for 1997-2001.) June 1995 - Eighteenth Session of the IOC Assembly decided to hold at each Assembly a “Dr Panikkar Lecture” in recognition of his input to the IOC and particularly its TEMA programme. (The lectures will address capacity building in marine science issues at regional and/or national levels.) June 1995 - IOC became a co-sponsor of the Floating University project which was operated by UNESCO since 1990. (The Floating University Cruise of 1995 was included in the list of events for the celebration ofthe Fiftieth Anniversary ofthe United Nations. Annual reports are published and workshops and seminars are arranged regularly where scientific results of cruises are presented.) 1996 - The IGOSS-IODE data management strategy was published in support of GOOS. 1996 - The series of GLOSS manuals was started with the publication of the first two volumes on sea-level measurement and interpretation. (Volume 3 will be completed by the end of 2000.) The GLOSS Station Handbook containing a comprehensive database of information about 308 59 tide gauge stations was published. In the same year, the Handbook was transferred onto CDROM. The CD-ROM also contains an overview of the GLOSS system and a complete listing of the 72,500 station year of sea-level data held by PSMSL and covering 1,750 stations worldwide. 1996-1998 - The first sheets of the IBC for the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, and for the Eastern Atlantic were printed. March 1996 - OOPC (Ocean Observations Panel for Climate) was established as a follow-up to OOSDP (Ocean Observing System Development Panel). (The OOPC generates activities leading to updating and implementation of the OOSDP design plan. It produced the specification for the initial observing system.) 1997 - IOC initiated efforts towards facilitating and co-ordinating a requisite unified research programme in the Mediterranean complemented by operational oceanography and coastal area management science and activities. 1997 - The Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM) was adopted as an independent programme by the Nineteenth Session of the IOC Assembly. (In November 1998 the programme strategy was defined. The ICAM programme is the follow-up to UNCED with the objective of assisting IOC Member States in their efforts to build marine scientific and technological capabilities in the field of integrated coastal management.) 1997 - The Methodological Guide to Integrated Coastal Area Management was published. 1998 - Strategic Plan and Principles for GOOS, as well as the Global Ocean Observing System Prospectus were published. 1998 - The International Year ofthe Ocean (IYO), EXPO ‘98 was held. “The Ocean Charter” was written and signed by almost 1 million persons and many governmental officials in recognition of the wisdom of acting in unison to protect the oceans and to use their resources in a sustainable manner. May 1998 - IOC co-sponsored the International Conference on Ocean Circulation and Climate in Halifax, Canada, with the purpose of reporting at the mid-life of WOCE on achievements thus far and presenting the first results that show a far more active picture of the deep circulation than formerly believed. IOC was a co-sponsor. (Pan African Conference on Sustainable Integrated Coastal Management) Conference was held in Maputo, Mozambique, on 18-25 July. July 1998 - The PACSICOM 1998 - The Seychelles Atlas on Sensitivity of Coastal Shallow Areas was published. 1998 - The European Union (EU) started the 3-year MEDARMEDATLAS-II project as a regional contribution to GODAR with the objective of rescuing, safeguarding and making available a comprehensive dataset of oceanographic parameters collected in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. (IOC is assisting in the project implementation.) 1998 - The Director-General of UNESCO commissioned an External Evaluation of IOC by a group of independent experts. 60 November 1998 - The First Youth Forum on Oceans was held in conjunction with the Thirty-first Session of the IOC Executive Council where the results of the IYO were presented. The Forum formulated a statement with the commitment to the principles presented in the Ocean Charter. December 1998 - The GOOS Memorandum of Understanding between IOC, WMO, UNEP and ICSU was revised to create the GOOS Steering Committee. 1999 - A CD-ROM with geophysical data from the Mediterranean Seaand a CD-ROM containing data and information on geology, geophysics and non-living resources of the Indian Ocean were developed with financial support from IOC. July 1999 - A new internal mechanism to co-ordinate TEMA component activities across all IOC programmes was established within the IOC Secretariat. October 1999 - First International Conference on Ocean Observations for Climate was organized at St Raphael, France, with the purpose of building consensus and defining the optimum mix of measurements, as well as the data management and modelling activities needed to meet the goals of climate programmes. October-November 1999 - Thirtieth General Conference of UNESCO approved revised statutes for the IOC as a body with functional autonomy within UNESCO with the purpose “to promote international co-operation and co-ordinate programmes in research, services and capacity building, in order to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas and to apply that knowledge for the improvement of management, sustainable development, the protection of the marine environment and the decision-making processes of its Member States”. 61 APPENDIX C IOC STATUTES Article 1 - The Commission 1. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission,. hereafter called the Commission, is established as a body with functional autonomy within the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2. The Commission defines and implements its programme according to its stated purposes and functions and within the framework of the budget adopted by its Assembly and the General Conference of UNESCO. Article 2 - Purpose of the Commission 1. The purpose of the Commission is to promote international cooperation and to coordinate programmes in research, services and capacity-building, in order to learn more about the nature and resources of the ocean and coastal areas and to apply that knowledge for the improvement of management, sustainable development, the protection of the marine environment, and the decision-making processes of its Member States. 2. The Commission will collaborate with international organizations concerned with the work of the Commission, and specially with those organizations of the United Nations system, which are willing and prepared to contribute to the purpose and functions of the Commission and/or to seek advice and cooperation in the field of ocean and coastal area scientific research, related services and capacity-building. Article 1. 3 - Functions The functions of the Commission shall be to: (a> recommend, promote, plan and coordinate international ocean and. coastal area programmes in research, observations and dissemination and use of their results; (b) recommend, promote and coordinate the development of relevant standards, reference materials, guidelines and nomenclature; (cl respond, as a competent international organization, to the requirements deriving from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), and other international instruments relevant to marine scientific research, related services and capacity-building; (4 make recommendations and coordinate programmes in education, training and assistance in marine science, ocean and coastal observations and the transfer of related technology; 62 Cd make recommendations and provide technical guidance to relevant intersectoral activities of UNESCO and undertake mutually agreed duties within the mandate of the Commission; (0 undertake, as appropriate, any other action compatible with its purpose and functions. 2. The Commission shall prepare regular reports on its activities, which shall be submitted to the General Conference of UNESCO. These reports shall also be addressed to the Member States of the Commission as well as to the organizations within the United Nations system covered by paragraph 2 of Article 2. 3. The Commission shall decide upon the mechanisms and arrangements through which it may obtain advice. 4. The Commission, in carrying out its functions, shall take into account the special needs and interests of developing countries, including in particular the need to further the capabilities of these countries in scientific research and observations of the oceans and coastal areas and related technology. 5. Nothing in these Statutes shall imply the adoption of a position by the Commission regarding the nature or extent of the jurisdiction of coastal States in general or of any coastal State in particular. Article 4 - Membership A. Membership 1. Membership of the Commission shall be open to any Member State of any one of the organizations of the United Nations system. 2. States covered by the terms of paragraph 1 above shall acquire membership of the Commission by notifying the Director-General of UNESCO. 3. Any Member State of the Commission can withdraw by giving notice of its intention to do so to the Director-General of UNESCO. 4. The Director-General of UNESCO shall inform the Executive Secretary of the Commission of all notifications received under the present Article. Membership will take effect from the date on which the notification is received by the Executive Secretary. Notice of withdrawal will take effect one full year after the date on which the notice is received by the Executive Secretary, through the Director-General of UNESCO. The Executive Secretary will inform Member States of the Commission and the Executive Heads of the relevant United Nations organizations of all notifications. B. 5. Responsibilities of Member States The responsibilities of Member States imply: (9 compliance with the Statutes and Rules of Procedure of the Commission; 63 6. (ii) collaboration with and support of the programme of work of the Commission; (iii) specification of the national coordinating body for liaison with the Commission; (iv) support of the Commission at an appropriate level using any or all-of the financial mechanisms listed under Article 10. The notification by a Member State requesting membership shall include a statement indicating acceptance of the above responsibilities or its intention to comply at an early date. Article 5 - Organs The Commission shall consist of an Assembly, an Executive Council, a Secretariat and such subsidiary bodies it may establish. Article 6 - The Assembly A. 1. Composition The Assembly shall consist of all States Members of the Commission. B. Functions and powers 2. The Assembly is the principal organ of the Commission and shall perform all functions of the Commission unless otherwise regulated by these Statutes or delegated by the Assembly to other organs of the Commission. 3. The Assembly shall determine the Commission’s Rules of Procedure. 4. The Assembly shall establish general policy and the main lines of work of the Commission, and shall approve the IOC Biennial Draft Programme and Budget in accordance with paragraph 2 of Article 1. 5. During the course of each ordinary session, the Assembly shall elect a Chairperson and, taking into account the principles of geographic distribution, shall elect five ViceChairpersons who shall be the officers of the Commission, its Assembly and its Executive Council, and shall also elect a number of Member States to the Executive Council in accordance with Article 7. 6. In electing Member States to the Executive Council, the Assembly shall take into consideration a balanced geographical distribution, as well as their willingness to participate in the work of the Executive Council. C. Procedure 7. The Assembly shall be convened in ordinary session every two years. 8. Extraordinary sessions may be convened if so decided or if summoned by the Executive Council, or.at the request of at least one third of the Member States of the Commission under conditions specified in the Rules of Procedure. 64 9. Each Member State shall have one vote and may send to sessions of the Assembly such representatives, alternates and advisers, as it deems necessary. 10. Subject to provisions in the Rules of Procedure regarding closed meetings, participation in the meetings of the Assembly, of the Executive Council and subsidiary bodies, without the right to vote, is open to: I 1. (4 representatives of Member States of organizations of the United Nations system which are not members of the Commission; (b) representatives of the organizations of the United Nations system; cc> representatives of such other intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations as may be invited subject to conditions specified in the Rules of Procedure. The Assembly may set up committees or other subsidiary bodies as may be necessary for its purpose, in accordance with conditions specified in the Rules of Procedure. Article 7 - The Executive A. Council Composition 1. The Executive Council shall consist of up to 40 Member States, including those Member States represented by the Chairperson and the five Vice-Chairpersons. 2. The mandate of the members of the Executive Council shall commence at the end of the session of the Assembly during which they have been elected and expire at the end of the next session of the Assembly. 3. In selecting representatives to the Executive Council, Member States elected to the Executive Council shall endeavour to appoint persons experienced in matters related to the Commission. 4. In the event of the withdrawal from the Commission of a Member State that is Member of the Executive Council, its mandate shall be terminated on the date the withdrawal becomes effective. 5. Members of the Executive Council are eligible for re-election. B. Functions and powers 6. The Executive Council shall exercise the responsibilities delegated to it by the Assembly and act on its behalf in the implementation of decisions of the Assembly. 7. The Executive Council may set up committees or other subsidiary bodies as may be necessary for its purpose, in accordance with conditions specified in the Rules of Procedure. 65 C. Procedure 8. The Executive Council shall hold ordinary and extraordinary sessions as specified in the Rules of Procedure. 9. At its meetings, each Member State of the Executive Council shall have one vote. 10. The agenda of the Executive Council should be organized as specified in the Rules of Procedure. 11. The Executive Council shall make recommendations on future actions by the Assembly. Article 8 - The Secretariat 1. With due regard to the applicable Staff Regulations and Rules of UNESCO, the Secretariat of the Commission shall consist of the Executive Secretary and such other staff as may be necessary, provided by UNESCO, as well as such personnel as may be provided, at their expense, by other organizations, the United Nations system, and by Member States of the Commission. 2. The Executive Secretary of the Commission, at the level of Assistant Direc:tor-General, shall be appointed by the Director-General of UNESCO following consultation with the Executive Council of the Commission. Article 9 - Committees and other subsidiary bodies 1. The Commission may create, for the examination and execution of specific activities, subsidiary bodies composed of Member States or individual experts, after consultation with the Member States concerned. 2. To further the cooperation referred to in Article 11, other subsidiary bodies composed of Member States or individuals may also be established or convened by the Commission jointly with other organizations. The inclusion of individuals in such subsidiary bodies would be subject to consultations with the Member States concerned. Article 1. 2. 10 - Financial and other resources The financial resources of the Commission shall consist of: (i) funds appropriated for this purpose by the General Conference of UNESCO; (ii) contributions by Member States of the Commission, that are not Member States of UNESCO; (iii) additional resources as may be made available by Member States of the Commission, appropriate organizations of the United Nations system and from other sources. The programmes or activities sponsored and coordinated by the Commission and recommended to its Member States for their concerted action shall be carried out with 66 the aid of the resources of the participating Member States in such programmes or activities, in accordance with the obligations that each State is willing to assume. 3. Voluntary contributions may be accepted and established as trust funds-in accordance with the financial regulations of the Special Account of IOC, as adopted by the Assembly and UNESCO. Such contributions shall be allocated by the Commission for its programme of activities. 4. The Commission can establish, promote or coordinate, as appropriate, additional financial arrangements to ensure the implementation of an effective and continuing programme at global and/or regional levels. Article 11 - Relations with other organizations 1. The Commission may cooperate with Specialized Agencies of the United Nations and other international organizations whose interests and activities are related to its purpose, including signing memoranda of understating with regard to cooperation. 2. The Commission shall give due attention to supporting the objectives of international organizations with which it collaborates. On the other hand, the Commission shall request these organizations to take its requirements into account in planning and executing their own programmes. 3. The Commission may act also as a joint specialized mechanism of the organizations of the United Nations system that have agreed to use the Commission for discharging certain of their responsibilities in the fields of marine sciences and ocean services, and have agreed accordingly to sustain the work of the Commission. Article 12 - Amendments The General Conference of UNESCO may amend these Statutes following a recommendation of, or after consultation with, the Assembly of the Commission. Unless otherwise provided by the General Conference, an amendment of these Statutes shall enter into force on the date of its adoption by the General Conference. 67 APPENDIX IOC ORGANIZATION AND PROGRAMME I I I ASSEMBLY EXECUTIVE EXECUTIVE STRUCTURE I COUNCIL SECRETARY 1 1 SECRETARIAT + Ocean Science Operatlonal Oceans and Climate (WCRP, OOPC. GODAE, JGOFS, CLIVAR. El Nino) Ocean Science in Relation to Living Marine Resources, OSLR (HAB, GCRMN. GLOBEC, LME. SAHFOS) Marine Pollution and Monitoring (GIPME, MEL) l l l Observing Systems Global Ocean Observing System, GOOS International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange, IODE (GODAR. MIM, GLODIR, GTSPP, RECOSCIX ODINEA. GETADE. OceanPC) GOOS Modules (Climate, Coastal, Health of the Ocean, Living Marine Resources) IDNDR-Related Activities: International Tsunami Warning System (ITSU) Storm Surges Disaster Reduction Integrated Global Observing Strategy, IGOS Research . Science for Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM, COASTS, OCEANS 21) Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Living Resources, OSNLR Joint Technical Commission for Oceanography and Marine Meteorology, JCOMM (DBCP.IGOSS, Argo, TAO, GLOSS) . Global Climate Observing System, GCOS . Remote Sensing Ocean Mapping (GEBCO, GAPA. IBCM) Public Information (IOC Website, Newskstter) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 0 0 i EDUCATION AND MUTUAL ASS REGIONS Regional Sub-Commissions, Committees other specific programmes I IOCARIBE l :....... .............. ............1 I ] Casoian Sea . Persian Gulf, Red Sea and Gulf of Aden IOCINDIO ; . Mediterranean . Africa (PACSICOM) and I’.... ..... ...... .... ... . ..t j IOCINCWIO j I BlackSea D ! 69 I I IOC SECRETARIAT I, 2 !I i APPENDIX E 71 APPENDIX IOC RESOURCES AND F BUDGET This appendix provides summary information on the overall resource situation of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) over the past decade. The financial resources available for carrying out the work of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) consist of: funds approved for this purpose by the General Conference of UNESCO, including: (a> . personnel costs associated with staffing of the approved UNESCO permanent posts in the IOC Secretariat, . programme funds made available from the UNESCO Regular Budget for expenditure by the IOC Secretariat, . resources made available in-kind from within UNESCO Administration for support of the work of the IOC in the form of accommodation, meeting facilities, accounting support, documentation, etc, but not explicitly attributed to the IOC; contributions by Member States of the Commission that are not Member States of (b) UNESCO; additional resources as may be made available by Member States of the Commission, (cl appropriate organizations of the United Nations system and from other sources. The financial resources made available from within the UNESCO Regular Budget ((a) above) are administered through UNESCO in accordance with the UNESCO Financial Regulations but only the first two sub-categories (personnel costs and programme funds) are normally explicitly identified as IOC resources. The resources contributed by Member States and collaborating organizations ((b) an.d(c) above) for the implementation of IOC programmes fall into two main categories: . resources provided directly (as financial contributions to the IOC Trust Fund or through staff secondment, in-kind support and the like) to the IOC for administration under the authority of the Executive Secretary; . national or institutional resources which remain fully under the control of Members or cooperating organizations but which are part of the coordinated implemenltation of the agreed IOC Programme. On this basis, the historical resourcing of the IOC can be represented approximately in terms of biennial income (and expenditure) as: . UNESCO Regular Budget: Personnel costs Programme expenditure . IOC Trust Fund (Personnel costs and programme expenditure). The biennial income/expenditure from 1990-9 1 to 1998-99 and the budget for 2000-O 1 may thus be summarised as follows (US$OOO): __i_--- -._ - -----l_..l_ .“--- 72 UNESCO REGULAR BUDGET IOC TRUST FUND BIENNIUM Personnel costs Programme Expenditure 1990-91* 2072 1992-93* 3637 TOTAL I 10404 1994-95 * 3300 4013 3469 10782 1996-97 3359 3065 4947 11371 1998-99 3603 3066 4549 11218 2000-01** 3663 2960 4000 10623 * ** IOC and marine-related issues Trust Fund component estimated This financial summary for the past decade does not enable separation of Trust Fund expenditure into personnel and programme costs but the most recently published IOC Annual Report does provide a separation of the annual income/expenditure for 1998 as follows (US$OOO): SOURCE OF FUNDS UNESCO Regular Budget IOC Trust Fund ITOTAL I TOTAL Personnel costs Programme Expenditure 1830.850 1380.000 3210.850 766.240 1464.642 2230.882 2597.090 I 2844.642 I 5441.732 4 I Although a detailed budget breakdown in line with the new programme structure summarised in Appendix D is not available, an indicative breakdown of total annual IOC expenditure (in percentage and US$ terms) can be estimated as follows: PROGRAMME/ACTIVITIES PERCENT Ocean Science Operational Observing Systems Ocean Services Regional Activities Management and Coordination TOTAL BUDGET ($000) 30 25 15 15 15 I 100 I I 5500 I Useful indications of the distribution of Regular Budget resources by activity and object of expenditure are also available from the Session documents prepared for the consideration of the Draft Programme and Budget 2000-01 at the Twentieth Session of the Assembly in June-July 1999. These may be summarised as follows (Proposed expenditure 2000-01 in US$OOO): 73 PROGRAMME/ACTIVITY Oceans and climate 2000-01 Biennium ($000) 165 Oceans and global change 95 Ocean Science in Relation to Living Resources (OSLR) 95 Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Living Resources (OSNLR) 45 Global Investigation of Pollution in Marine Environment (GIPME) IIntegrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM) Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) 290 International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE) 215 International Coordination Group for the Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific (ITSU) and International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR) 65 Ocean Mapping 45 Capacity building (TEMA) 500 Regional programmes 500 Governing bodies and global policy 300 Assessment and evaluation 105 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) and interagency cooperation 165 Public awareness 140 The additional contribution from Trust Fund sources for 2000-O 1 can be summarised in terms of the breakdown of total budgeted expenditure into the two “Main Lines of Action” (MLA) identified in the UNESCO Draft Programme and Budget 2000-01 as follows: 74 UNESCO Regular Budget Extrabudgetary resources MLA 1: REDUCING SCIENTIFIC UNCERTAINTIES ABOUT COASTAL AND OCEANIC PROCESSES Ocean sciences and ocean services OSLR (part GOOS Living Marine Resources Model) Capacity building (500,000 x 80%) Regional programmes Governing bodies and global policy (300,000 x 80%) Assessment and evaluation Public awareness Sub-total 895 20 900 400 500 240 500 700 150 105 100 2260 2250 MLA 2: MEETING THE NEED OF OCEAN-RELATED CONVENTIONS AND PROGRAMMES 3cean and climate, oceans and global change 3SLR (GCRMN and HAB) Zapacity building (500,000 x 20%) Governing bodies and global policy (300,000 x 20%) JNCLOS, UNCED and interagency :ooperation ?ublic awareness Sub-total rOTAL 260 75 100 60 400 1200 165 150 140 700 1750 2960 4000 A further perspective on the breakdown of planned expenditure for 2000-O 1 is also provided from the Twentieth Assembly Programme and Budget documentation as follows: Grants 52 1793 1845 TOTAL 2960 4000 6960 75 Under this classification: . Personnel includes temporary appointments, translation and interpretation, consultants, overtime. . Consultations includes travel of participants and staff to expert consultations, meetings of IOC groups of experts, participation at UN and other meetings and advice to Member States. . Contractual services includes contracts other than those under “Fellowships” below. . General operating expenses includes communications, freight, hospitality, miscellaneous (but not Xerox, see below). . Supplies and materials includes office supplies, Xerox, library books and book/reprint orders, public information supplies, data processing supplies (but not equipment, see below). . Acquisition of furniture and equipment includes office furniture and equipment, data equipment. . Fellowships, grants and contributions includes fellowships and study grants, grants to seminars and training activities, including group training; contributions towards programme activities; subventions, contributions to joint activities within the UN; and framework agreements. .~-_.-. -.- -______- ---- 77 APPENDIX TERMS OF REFERENCE AND MEMBERSHIP THE EVALUATION TEAM G OF The terms of reference for the independent external evaluation of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO carried out over the period June 1999 to February 2000 were to: provide an objective and detailed review of the capacities and capabilities of IOC in (i> carrying out its mission; (ii) provide an assessmentof the current effectiveness of IOC programmes and IOC capacities to respond to changing needs and circumstances; (iii) provide an assessment of the IOC administrative effectiveness and efficiency; (iv) provide recommendations for the IOC future activities and related administration. The membership of the Evaluation Team consisted of: Dr John G Field, Professor, Zoology Department, University of Cape Town, South Africa and President of the ICSU (International Council for Science) Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR). Zoology Department Address: University of Cape Town 770 1 Rondebosch South Africa. Dr Elie Jarmache, Director of International Relations, Institut Francais de Recherche pour 1’Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER), Paris, France. IFREMER Address: 155 rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau 92 138 Issy-les-Moulineaux Cedex France. Dr John W Zillman, Professor in the School of Earth Sciences of the University of Melbourne, Chairman of the Australian Commonwealth Heads of Marine Agencies (HOMA), Director of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and President of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (Team Leader). Address: Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289K Melbourne, Victoria, 300 1 Australia. The Secretariat support for the conduct of the Evaluation was provided by Dr Iouri Oliounine, Deputy Executive Secretary of the IOC. Special assistance to the Evaluation Team was provided by consultants Mr Geoffrey L Holland (immediate past Chairman of the Commission) and Mr Martin Brown (economic c,onsultant). 79 APPENDIX QUESTIONNAIRE TO IOC MEMBER STATES INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION COMMI!%ION OCEANOGRAPHIQUE INTERGOUVERNEMENTALE COMISION OCEANOGRAFICA INTERGUBERNAMENTAL MEXllPABHTEJTbCTBEHHAR OKEAHO~AUW4ECIGUI KOMHCCHH UUESCO “Our Common Heritage” - 1, rue Miollis - 75732 Paris Cedex 15, Cbl: UNESCO Paris, llx: 204461 Paris, Fax: <33> 145 68 58 12, Tel: <33> 145 68 39 63, E-mail: i.oliouuine@unesco.org UNESCO Paris, 03 August 1999 Our ref. IO/sm IOC Circular (English Letter No. 1621 only) To: IOC Member States From: ADGAJNESCO, Executive SecretaryIOC Subject: External Evaluation of IOC Dear Madam/Sir, Pleasefid attached a qucsticrnneire regardiy tb External Evalua!ion of the !ntr+yvemmentrl OceanographicCommission (IOC) of UNESW held in Paris from 22-23 June 1999. I would appreciateit if you provide us with the required information by 15 SeDtember1999, through the IOC Secretariat,attention Dr. I. Oliounine. Yours sincerely, P. Bemal I’Executive SecretaryIOC Chairman Prof. Su Jilan Second ,“SttNte of Oceanography State Oceanic Admimstmt~on P.O. Bon 1207. Hattgzhw Zheijang 310012 CHINA Vice-Chairmen Dr. David T. Pugh Soulhampton Oceanography Empress Do& Swthmptott SO14 32H UNITED KINGDOM Exacutive Scretary Dr. Patrtcio Bemal Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission _ UNESCO I, NC Miollis 75732 Paris Ccdex IS FRANCE Vice-Admiral Marcus Lral de Azwedo Diiol Directotia de Hidmgtafia e Navegw Rua Barb de Jaceguay rltt Ponta da Army&~ 24048-900 Niterdi. RI BRAZIL Centre Dr. Sergey s. Khodktn Deputy Head, Russian Federal Hydrometcomlogy and EnvtmntnentaJ Monnonng Novovagttttkovslty St. 12 Moscow 123 242 RUSSIAN FEDERATION Serwe for Dr. Thomas Olantnde AJayi Director. Nigerian h.SttNte for Oceanography and Marine Research Federal Ministry of Agnculture. Water Resources and Rural Development Wilma Pomt Road. Victona Island P.M.B. 12729 Lagos NIGERIA H 80 EXTERNALEVALUATIQNOIFTHEIW QUESTKOiVNAIRE TO IOCACTIONADDR~EES To assist the Exrenal Evaluation Team in Its evaluatian of the current capabilities and effectiveness of the IOC and in the formulation of its recommendations to the Executive Board of UNESCO. ICYC Member StaResare invited EOprovide answers ta the: following questions: IDENTIFICATICKV A? QF I?Esl”ONRER~ PERSON COMPLETING l TM4 QtJE!3TKWNAIRE .................................................................... (Name) .................... ..~.~*....~~.....~..~..~.....~..~..........~.. (Address) ...................................................... (position/authority) l This identification page will bedetached before processing ofthe questionnaireand isrequested to be filled forauthentitication purposes alone. The anal><ical information requested from Member States is contained in items I & 2. I. COUNTRY CHARACTERUAT?QN GNP in USS tmillions) A?. 0500-f.ooa CJ1.000-5.ooo m.ooo-10.ooo u mmo-2aooo u>20.ooo Population . .. Length of the Cortstline . Signatop of UNCLOS aYes . . . . . .. . . .. . . ._.. ON0 very Low I 2 3 1 Ven High 5 cl 0 u cl n 0 Cl cl 0 ci’ Cl cl a Cl C a cl 0 e Cl Coastal tourism a 0 a a Cl Coastal development 0 cl 17 Cl CI RELATIVE IMRXULWCE ECONOMIC ACTIV’FTIES O‘F THE FOLLQwlNc Fisheries (mva0tive.U Fisheries (small-s&e) Offshore oil Shipping 3. ac50a Very low I 2 3 high 4 0 Cl I3 cl 0 a 0 cl q a 0 cl 0 a cl cl 2 3 VeT high 4 of the IOC 0 cl (b) The efficiency Assembly of the work of the a 0 of the Executive cl 0 (c) The efficiency Council II a (d) The efficiency of the IOC Secretariat EFFECTWENESS OF KX How do you currently rate : (a) The overall &ectiveness Very of IOC (b) IOC’s Global programmes (c) IOC’s Regional programmes Ed) DC’s 4. EFFICIENCY Joint programmes with other bodies OF IOC Ho\% do you currently rate: (a) The over4 eficiency 2 82 s. 1. VALUE OF IOC TO YOUR COWTRY V-w VerY IOW 1 2 3 4 high 9 the IOC u a u u cl (b) IOC uok rn ocean sciences u a cl a u (C) IOC u0A In ocean services cl a n 17 u cI q u a a cl u q cl a HOH do you currently (a) The overall balueof rate: Id) IOC work in ocean observing (e) IOC wark in capacity building d IOC Priority of your country Afready participating Would like to participate very low I2 Yes Na YCS VO auoaa a u a 0 uuaau u u cl a (c) Ocean science in relation to nonliving resources (OSLNR) auoau u cl n a (d) IODE (data and information) nu au0 0 17 cl 0 q I7 ffucl 5 u u 17 cl cl q uu u 17 u n 00000 u cl a q Cl 0 q clcl 0 n a 0 cl 0 uuu a u cl cl PARTICIP’ATfOS PROCR&MMES IX (a) Oceans and climate (b) Ocean science in relation living resources (OSLR) tu very high 345 (e) Tsunami! Storm surges ( D Ocean mapping (g) ICAM ( Inte-grated Coastal Area Managment) (h) Marine Pollution (i) OS. s) stems including operating 3 83 7 YATIONA;t ARRANGCMEXI-S PARTICtP.ATIO3 fN WC FOR (a) Approsimately how many agencies in \our country are actively tn\ol\rd in !OC programmes (h) Approximatei! how man) jclen~ls1S in?ourcounn~arcacti~bj mvolhed in 1OC programmes .._.......“..........._._... (c) Do you have a Nation& Commitee for IOC DYes ON0 (cl) If yes. is it part of the Ni&n2k Commissian for UNDSCO high t0Vd (e) How efkaive I 2 3 4 5 u n cl cl 0 do you conskien national co-ardination your arrangments for ICC ........................................................................................ ( tJ Elaborate briefly on your national ca-ordinati.on [institutions governmental arrangments parricipaeiag. level. etc.) ........................................................................................ .... ..............~_............-...~..~..~.~.........~.~...-..........-~..................................................................................................... ........................ ........._...............-.~.....................~--..-.......- 8. n;TURE DIEVEl.OP.MENT OF -I-HE IOC Would you/your countty favour. (a) Higher/lower Budget funding I h) Higherilower Higher About right Lower 5 cl a q n a 0 MOE 0 Aboutright Less 0 0 q of q cl q of cl 0 17 with cl u cl 0 cl 0 levels of Regular kvelsofpemmerrt jrafling (c) Higher/lower funding (d) More/less levels of voluntary individuai IOC programmes (e) More/less regional programme activities focus (f) More/less decentralisation Secretariat from Paris (g) Moreiless coltaboration other orpanizations (h) More/less emphasis on public awareness of IOC role and activities 4 q 84 ( i) .Vore/ less use ofetpens seconded by countries far programmes coordination . 0 u a !j) More/less meetings of subsicky bodies a a 0 (k) increxx’decrease consultants in Secretariat u 0 cl use of 9. Please provide any views, you would like the Evaluation Team M coasider on the current performance artdh htwe dcvelop~1101t and oper&on of the IOC Foptianal): .................................................................................. ..................................................... ..........._................~ ...._..............--.._..........-......-.........-_.......................... ..............._................................~..................... ....................................-.............................-..... .......______._........~...........................~..~................. ..... .._.....-..................................................................... ....................................... ...._................-..................................................................................................... .................................................................................. ......................~..........-............................................... 85 APPENDIX SUMMARY ANALYSIS OF RESPONSES TO EVALUATION I QUESTIONNAIRE The questionnaire included nine sections to be completed by national respondents as follows: country characterization; (1) relative importance of economic activities; (2) effectiveness of IOC; (3) efficiency of IOC; (4) value of IOC to countries; (5) participation in IOC programmes; (6) national arrangements for participation in IOC; (7) future development of the IOC; (8) general comments. (9) 2 For questions (2) to (6), IOC Action Addressees were invited to answer by rating their assessment on a scale from very 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). 3 The questionnaire was sent to all 127 Member States of IOC. 4 The Evaluation Team received 4 1 answers which represented a response ratio of 32%. In absolute terms, this ratio seems rather low, but the responses included most of the active Members of the Commission and represented close to half of the usual attendance at an Assembly session. Classification by region showed three regions sending almost the same number of 5 answers: Latin and Central America 10, Asia 11, Europe 12. From Africa there were 6 answers, with 2 out of the 6 from Arab Mediterranean countries, 2 from Indian Ocean States and one answer from the west coast of Africa. One response was received from North America and one from the Pacific area. 6 Some of the responses were ambiguous in that, occasionally, more than one box was ticked and, in a few cases,marginal comments appeared to disagree with the rating given. Several respondents chose not to complete certain questions. No respondent provided information on all items. 7 A tabular summary of respondents for those questions which involved a rating, l-5 is given overleaf. In summary and using the totals of ratings 3-5 as a general indicator of positive support/importance: . Importance of economic activities. Coastal development (37), shipping (35) and coastal tourism (35) emerged as the most important economic activities. . Effectiveness of the IOC. The IOC received a fairly high total of positive ratings (32) for overall effectiveness with its global programmes (32) and joint programmes (30) rating higher than its regional programmes (22). There appears to be a difficul.ty with the regional programmes with almost half the respondents responding negatively. . Efficiency of the IOC. Although the number of positive (rating 3-5) responses on the overall efficiency of the IOC was 27, the separate ratings of the efficiency of the Assembly, Executive Council and Secretariat were all higher, with the Secretariat (35, of which 21 were rating 4) conspicuously the most highly rated. . Value. All components of the work of the IOC except capacity building (24) received 28 or more positive ratings. 86 . Priority. All the identified programme areas received high (rating 3-5) priority ratings of 27 or more, except Ocean Science in Relation in Non-living Resources (23) and Tsunami/Storm Surges (15). The analysis of the remaining questions did not permit of simple summary but the 8 conclusions, and particularly the Member comments, were fully taken into account by the Evaluation Team in reaching its overall interpretation of Members’ views from the sample represented. RATING ITEM TOTAL 2 3 1 1 10 1 3 0 7 9 5 2 1 2 10 10 4 10 10 13 4 15 613 6 9 11 14 5 20 8 16 37 39 34 38 39 39 EFFECTIVENESS OF THE IOC Overall effectiveness Global programmes Regional programmes Joint programmes 1 2 1 1 2 4 15 6 23 16 7 18 7 14 14 11 2 2 1 1 35 38 38 37 EFFICIENCY OF THE IOC Overall efficiency Assembly Executive Council Secretariat 1 0 1 0 11 8 5 3 13 21 16 10 9 6 9 21 5 4 4 4 39 39 35 38 VALUE Overall Ocean science Ocean services Ocean observing Capacity building 2 3 2 2 2 7 7 5 6 11 11 10 10 10 11 11 11 14 13 10 7 7 7 7 4 38 38 38 38 38 4 4 5 4 4 11 3 6 10 10 13 8 15 10 5 36 37 39 2 3 7 14 9 35 6 6 51011 4 11 7 3 3 8 3 6 6 12 10 16 34 34 38 37 36 IMPORTANCE OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY Fisheries (extractive) Fisheries (small scale) Offshore oil Shipping Coastal tourism Coastal development PRIORITY FOR PARTICIPATION Oceans and Climate Ocean Science in Relation to Living Resources Ocean Science in Relation to Non-Living Resources International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE) Tsunami/Storm Surges Ocean Mapping Integrated Coastal Area Management Marine Pollution Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) 13 2 3 4 2 4 5 1 8 13 7 87 APPENDIX THE EVALUATION J OF WESTPAC Two members of the external Evaluation Team (Field and Zillman) visited the IOC-WESTPAC Office in Bangkok from December 2 - 5, 1999. During this period they interviewed: . Dr Shigeki MITSUMOTO (UNESCO-IOC staff); . Mr Maarten KUIJPER (Seconded/contract staff); . Prof. Manuwadi HUNGSPREUGS (Vice-chair, WESTPAC); . Mr Agapito MBA-MOKUY (UNESCO admin and finance unit, Bangkok); . Dr Anond SNIDVONGS (Chulalongkorn Univ., Project leader); . Mr JIAN Yihang (UNEP, Bangkok, and former IOCAJNESCO staff) The evaluators thank all the above for their time, hospitality and constructive comments. They particularly thank Mr Kuijper and Dr Mitsumoto for the detailed document they preptared for the evaluation. This greatly aided in the task. THE WESTPAC SUB-COMMISSION This body meets in session every three years. It is headed by a chair (Prof. Taira, Japan) and two vice-chairs, one of whom is based in Bangkok and regularly visits the office. The SubCommission has 20 Member States, differing greatly in their involvement with WESTPAC and its programmes. There are two main types of programmes: Those generated from “the bottom up” by regional needs (eg Gulf of Thailand Project), (1) and Those generated “top-down” as regional components of global programmes (eg GOOS). (2) The programmes are grouped to correspond with the same categories as the central IOC categories (eg OSLR, etc). WESTPAC PROGRAMMES These include: 1.1 Gulf of Thailand Co-operative Study: A very successful project amongst 5 countries of the region involving monitoring, data management and data exchange, scientific research and capacity building, and communication with decision makers and the public. This programme is unlikely to have happened without the regional secretariat. 1.2 Mussel Watch: This project took a long time to get going in this region, and then only with limited funding. A report on the first workshop is still outstanding and follow up is required. 1.3 Paleogeographic map: This regional initiative has been an academic succes’s,although it still needs funds to publish the third map. 1.4 Ocean Dynamics and Climate; This project includes a study of the Indonesian throughflow, of great interest in understanding global circulation. 1.5 Harmful Algal Blooms: This longstanding programme (started 1987) has enjoyed great successand is important in the region, with many countries relying so heavily on fisheries and mariculture. It has links with the international GEOHAB programme. 1.6 NEARGOOS: This programme is now making steady progress amongst the Member countries (China, Japan, Korea. Russia). It is administered mainly from .Paris. 1.7 TEMA: Training . Education and Mutual Assistance are built into all prqjects of the region and not separated. There is a move to establish a post-graduate: school of 88 oceanography in the region which would probably operate mainly via the World Wide Web. REGIONAL SECRETARIAT The regional secretariat is housed in the headquarters of the National Research Council of Thailand (IVRCT) in Bangkok, in very adequate offices. The NRCT falls under the Ministry of Science in Thailand and is responsible for co-ordinating all scientific research in Thailand, including marine research, and has a staff of some 400 people. The NRCT provides the offices, a secretary and clerk, and pays for basic services. The arrangement seems to function well and the secretariat has a very good strategic location both in Thailand and in the region. There are great advantages in being in Bangkok, which houses so many regional headquarters, for UNESCO and many other bodies, such as UNEP. There are good links with local universities, in particular through Prof. Manuwadi Hungspreugs and Dr Anond Snidvongs. It should be noted that it took some six years of negotiation between deciding to open a regional office in Bangkok, and actually opening the office in the NRCT building in 1994. The budget is controlled from IOC headquarters. In 1999 it consisted of US$83,000 of Regular Programme funds, US$30,000 of Extra-budgetary funds (SIDA-SAREC) and some US$75,000 in Japanesefunds earmarked for IOC-WESTPAC. In the past, there has been uncertainty as to the availability of some of these funds for a good part of the year. These funds have been released to Bangkok as they are spent. but recently this has been streamlined into lump sums approximately every 3 months. The Secretariat is responsible for administering the WESTPAC Programmes, arranging meetings and workshops, and for keeping in good communication with both Member countries and with the IOC headquarters. To this end it produces a newsletter at six-monthly intervals. However, the last newsletter appeared in July 1998, and it appears that WESTPAC is losing visibility amongst marine scientists and authorities in the region. PERSONNEL The Secretariat was initially staffed by an IOC Assistant Secretary for WESTPAC on short-term contracts (Mr JIANG Yihang) who established the office after serving in Paris for several years. Thus he knew the ropes from the start. Dr Mitsumoto arrived in April 1997 and occupies a P4 Post. Mr Kuijper arrived in July 1997 as a P2 consultant, seconded from the Netherlands. In mid1998 Mr Jiang left to join the UNEP office in Bangkok at the P3 level. Thus the secretariat consisted of 3 professional staff plus two support staff for about a year (mid-1997 until mid1998). The present level of staffing of the Secretariat appears to be appropriate. However, it cannot be said to be operating at optimal efficiency. CONCLUSIONS 1 2 3 AND RECOMMENDATIONS The WESTPAC Secretariat performs a very useful function in the region and should be maintained. The Secretariat is well-located in near optimal conditions to serve WESTPAC and the present arrangement with NRCT should be continued. Some changes to staffing and working arrangements are urgently needed. 89 4 5 6 7 8 The office needs dynamic leadership with vision, initiative and the ability to inspire confidence in the scientific community and raise the profile of WESTPAC within the region. Any new professional appointees to regional offices would benefit greatly from several months prior work experience in IOC headquarters. The efficiency of the office could be enhanced by more systematic resource planning in the office, and increased devolution of the budget from headquarters on a six-monthly or annual basis. Given the present funding climate, consideration should be given for the secretariat to act as a co-ordinating and implementing agency for projects funded from outside the IOC. The future role of the secretariat should build on the commendable progress already made in establishing effective working relationships with UNESCO-PROAP, UNEP, and other regional 0fIices. 91 APPENDIX ECONOMIC EVALUATION AND IOC ACTIVITIES (Table of Contents of Consultant Report by Mr Brown) 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EVALUATION 3 PUBLIC GOODS, BENEFITS AND FINANCE FOR MARINE S&T 4 APPROACHES TO ECONOMIC EVALUATION 5 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 SOCIO-ECONOMIC COST/BENEFIT ANALYSIS Social Market Equilibrium Assumptions The accounting structure of CBA Project/programme definition Prices and valuation of costs and benefits Discounting, time periods and long term outcomes Sunk costs and benefits Shared costs and benefits 6 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 WHAT IS AVAILABLE ON MARINE S&T CBA? Introduction Economic value of marine activities Methodological studies of the benefits of climate forecasts The ENS0 studies SEAWATCH Europe North Sea Water Quality Information Service (NSWQIS) UK wave research Potential US Coastal Forecasting System (CFS) 7 POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF CURRENT/PROJECTED 8 8.1 8.2 COST/BENEFIT APPROACHES TO IOC EVALUATION The need for more economic evaluation of marine S&T Cost/benefits analysis for the IOC 9 CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PROGRAMMES OR S&T PROGRAMMES (CBA) IOC ACTIVITIES K