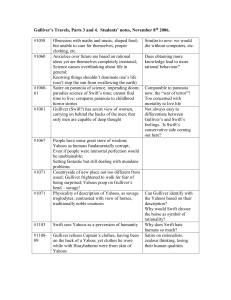

NAME:- FAHEEM ANWAR REGNO:- 2021158 NOVEL:- GULLIVER’S TRAVEL WRITTEN BY:- JONATHAN SWIFT GULLIVER’S VOYAGE TO LAND OF HOUYHNHNMS The fourth voyage lacks the picturesque and captivating illustrative and narrative detail so abundantly present in the first two voyages. There is, for instance, no double physical scale, and there is little narrative action. Swift does, of course, embody the chief elements of his sarcastic analysis in the actual symbols of the horse and the Yahoo, and he describes the Yohoo in complete and unpleasant detail. Even so, the spirit and scheme of the fourth voyage possess far less narrative richness than we find in the case of the first two voyages, because Swift now shifts the stress of his attack. The pasquinade of the first two voyages is affected with the flaws and defects of human actions. But the account of the fourth voyage cuts deeper. As actions are an index of human nature, the sarcasric satire of the last voyage deals with the motives and causes of action, and with the inner make-up of man. Moreover it has now become Swift’s intent to drive home the pasquinade insistently and relentlessly. Had he wished to achieve only the amusing and comic satire of the first two parts with occasional touches of the sarcastic variety, he need not have written the last part. But Swift went on, and in the fourth voyage corrosive satire becomes deep and heatless. In this part of the book, Swift sharply divides human nature into two parts. He attributes reason and benevolence to the Houyhnhnms, while the Yahoos are described as mere brutes with selfish appetites. Furthermore, Swift gives to the good qualities the non-human form of the horse, and to the bad qualities the nearly human form of the Yahoos. The satire would have been much less effectual if the Houyhnhnms had been depicted merely as a superior human race. The reader would in that case have naturally evaded the satirical attack by distinguishing himself with a Houyhnhnms. Again, for heat of attack, Swift dwells with harsh particularity on Yahoo form and nature: the emphasis is necessarily on Yahoo form and nature. In this connection, it may be pointed out that the unpleasant physical characteristics of the Yahoos are in themselves hardly as awful as the evil physical details which Gulliver has noted among the Brobdingnagians. The microscopic eye among the giants produces perhaps as repulsive a series of physical images as can be found in literature; but, for all that, we are conscious of a unreal enlargement, and this makes for relative unreality. The Yahoos are not giants; they resemble us all too closely in some ways, and their unpleasant physical attributes are shown to us without the variety of relief existing in Part II. Swift does not scant us anything in this last voyage. If he had made us heehaw and laugh at the Yahoos, and had amused us by depicting their activities, his corrosive pasquinade would have been fairly weakened. Similarly, if he had defined the Houyhnhnms so as to produce a comic effect, his chief purpose would have been flawed. Another noteworthy point is that in the first nine chapters of Part IV Swift further simplifies and focuses his attack by making almost no use of fun. The attack on the Yahoos (that is, human beings) is not only severe, but objective and direct. In the first nine chapters of the last voyage, the Yahoos (or the human beings) have been presented in all their horror. Swift has in these chapters achieved the most roaring and unrelieved satirical attack possible. Whatever can be said against the flaws and defects of human nature has been exhaustively said. Gulliver’s revolt against mankind is so complete that Swift is able to give the knife a final twist: mankind is, if anything, worse than the Yahoos, since man is afflicted by pride, and makes use of what mental power he has to achieve perversions and corruptions undreamed of even by the Yahoos. In Part IV, then, Swift gives a complete expression to his satirical vision, lashing his victims mercilessly. But he also realizes that the conclusions which have been drawn by Gulliver from this frightful vision are inadequate and invalid. The negative, corrosive attack by Swift on mankind is present up to the last page of the book. But what more Swift does in the last three chapters is unique in the history of satirical literature. Severe satire remains the main theme even in these chapters, but the new theme of Gulliver’s absurdity now complicates the issue. Swift rises to a larger and more comprehensive view than Gulliver, and in this way he satirically comments on the inadequacy of the corrosive attitude. The evils in the world and in man are such that a simple and ethical temperament may be driven to despair and misanthropy. Yet such an attitude is shown using Swift to be inadequate and absurd.