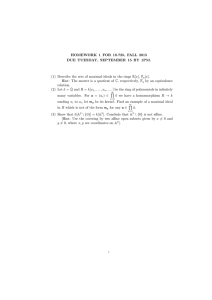

www.uka.org.uk/coaching Strength Series MAXIMAL STRENGTH: PART 1 By Derek Evely & Tom Crick Originally published in Athletics Weekly (www.athletics-weekly.com) Maximal Strength is one of the most popular topics in sport training culture today. An entire industry and marketplace has evolved surrounding the use of weight training and its application to sport. But is it effective or even necessary? Does it help or hinder athletic performance? Do all events require the implementation of a maximal strength program? Maximal, or absolute, strength is the ability to produce large amounts of force with a single concentric muscle contraction. Maximal strength does not relate to time constraints, so the amount of time required to develop force is not a consideration. Maximal strength also does not take into account the athlete’s body weight. In Athletics, we need our athletes to produce high forces relative to their bodyweight in very short amounts of time, so is there a place in any athlete’s program for maximal strength training? The key question to ask when designing a strength program involving maximal strength work is “why am I doing this?” Unfortunately, many coaches employ this kind of work in their programs without a clear reason for doing so. There are, or should be, two main rationales for why one implements any kind of training. The first has to do with the direct effect of the training one wants to implement. Ask yourself: “is there any direct transfer from this kind of work to the event I coach?” The two key areas in which maximal strength can have a direct transfer to performance is by helping an athlete to overcome inertia (i.e. direct force application) and to negotiate yielding forces, or changes in direction. If the event does not require the athlete to overcome inertia or negotiate rapid changes in direction then there is perhaps little to no point in improving maximal strength. The second rationale for employing a training method relates to laying a foundation for future work. In this case a coach should ask themselves: “if there is little direct transfer, am I then doing this work to lay a base for, or to augment, something else?” While one form of work may not transfer directly to the competitive event it may be essential in supporting another form of loading that does. For example, in one method of training known as “complex training”, maximal strength work is combined with reactive strength routines (plyometrics) in order to take advantage of the enhanced neural drive one experiences after lifting maximal loads, which tend to, if done properly, boost the reactive strength work. Research from Ireland shows that performing a squat exercise for five reps using close to maximal load about 3-5 minutes before performing a depth jump will result in the athlete being able to jump higher than they could under normal conditions. www.uka.org.uk/coaching While for the purposes of this article series we have broken up the main divisions of strength in order to examine them closely, it really helps here to remember that none of these can be viewed as segregated from one another. This cannot be stressed enough. An increase in maximal strength performance without corresponding increases in event-specific work is a red flag one needs to watch for. As we discussed in our last article, changes in one motor ability tends to have ripple effects in all others, hence the danger of viewing each in isolation of one another. So once a coach has decided that it would be appropriate to include some maximal strength work in their program, the next thing to ask is how much of this type of work is necessary and when should it be implemented. In order to answer these questions one really needs to look at the situation being discussed and the athletes in question. It is generally agreed that maximal strength training for younger athletes (or athletes without a preparatory strength base) is inappropriate. Why is this? Well, there are two primary reasons. The first is a no-brainer. The types of intensities we are talking about when discussing maximal strength are far too aggressive for the physical structures of most young or ill-prepared athletes. By “young” we are basically referring to pre-junior age athletes or athletes who are still growing rapidly, and by “ill-prepared” we are referring to athletes with little or no exposure to general strength routines designed to prepare an athlete for higher intensity work. The second reason is perhaps not so obvious to all coaches, as it has to do with the somewhat subjective concept of early specialisation in young athletes. Even if a young athlete can handle the physical demands of maximal strength loads there is the question of early specialisation. Maximal strength training is really a form of specialist strength training, and to implement such concentrated work in a young athlete’s program is to bring about a specialised response that may be way too early for an athlete’s own good, especially if they are gifted. The focus on this type of training early on in an athlete’s career may detract from or interfere with the development of essential abilities such as technique and speed training, abilities which if not developed early may be difficult to develop fully later on. Maximal strength, on the other hand, can generally be completely exploited at any time and so should be left until athletes are more fully developed. By now we agree (hopefully) that younger athletes need little or no maximal strength training. At the other end of the spectrum, it is becoming more and more evident that elite performers later in their careers may not need quite the volume of maximal strength training that they once did when developing. It seems that those who benefit most from this type of training are, generally speaking, U23 and early senior level athletes. So then for them it really becomes a question of how much is enough? Yes, there is probably a minimum level of maximal strength required for each speed/power event, but how does one know when enough is enough? How does one measure such a need? Other issues complicate matters further… what about the individual needs of athletes? Some may need more maximal strength work than others, so what does this say about “recipe” approaches to maximal strength implementation? What about event specific needs www.uka.org.uk/coaching and athlete physiology? Both play large roles in the load prescription. For instance, athletes loaded with the super fast type IIX fibers (often jumpers and throwers) may require unique quantities of maximal strength as they tend to respond intensely to this kind of work. Athletes with a large degree of endurance characteristics may adapt to this type of training differently and therefore their programs may need to reflect this. So now that we have a general overview of key issues surrounding maximal strength, it is time to define the exercise variables that play a part in developing it. Reps: The smallest unit we need to know about for this discussion is the repetition. Each time the athlete performs a movement, we count this as a “rep.” Because maximal strength relates to one single episode of force production, our reps during training will be kept low. Sets: Collections of reps are termed “sets” so if the athlete performs 5 squats in a row, then re-racks the bar to rest before starting another series of squats, this would be a set. Typically, multiple sets of each exercise are used when developing maximal strength. Exercise: Each movement pattern used during a maximal strength training session is referred to as an exercise. Exercises can be classified in a variety of ways, but for maximal strength training, many employ a very simple taxonomy, which categorizes exercises as upper body push (using the chest, shoulders, triceps), upper body pull (using the upper back and biceps) and leg exercises that involve the leg extensors and flexors. Tempo: The time it takes to perform each movement is the tempo of the exercise. As I squat, I may use a 5-2-5 tempo: 5 seconds lowering, a 2 second pause in my lowest position, followed by a 5 second ascent. Many different tempos can be used for maximal strength training, and varying the tempos is another method of stimulation the coach can use. Rest: Due to the intense nature of maximal strength training, rest breaks between sets of exercises and between the different exercises that make up the strength training session are necessarily long. Density: The training density is the total number of sessions of strength training per unit of time, usually expressed as sessions per microcycle, or week. Volume: The training volume is a very important indicator for the coach to monitor. A simple way to measure volume is simply to multiply the sets against the reps for a total. For example, today’s strength training may be 5 sets of 10 (50 reps total) and the next time, I may only do 5 sets of 8 reps (40 reps total). I can easily compare the rep totals and see that the volume for the second session is 80% of the volume for the first session. Intensity: While it is important to know the reps, sets, tempos and other exercise variables, the most important exercise variable for us to consider is intensity. Intensity refers to the percentage of maximum that the coach selects for training. Since maximal strength is expressed by maximal force produced by voluntary contraction, it is helpful to know a starting point, so intensities can be carefully prescribed and monitored. For example, if I am www.uka.org.uk/coaching able to squat 100kg, using 50kg as a training weight would represent an intensity of 50%. Over time, maximal voluntary force production increases (we hope), so periodic testing of maximal results for the various lifts being trained is indicated. Having testing data allows the coach to plan new intensities and check progress toward maximal strength goals. A word of caution: the stress that maximal lifting testing places on the athlete’s body is considerable, and much care should be taken to ensure adequate preparation, proper warm-up, and safety procedures in the weight room. Many athletes have been physically damaged by attempting to lift weights that they were not mentally or physically ready to lift. Always err on the side of caution. Just as intensities that are too high can result in injury, intensities that are too low will result in maximal strength stagnation. Having testing data allows the coach to assure that the athlete is operating in an intensity zone that will allow for improvement of maximal strength qualities. Now we have discussed the role of maximum strength training in athletics and described the key variables and parameters, in our next article we will examine some specific protocols that coaches use to develop maximal strength. A more in-depth discussion can be found in the Coach Cast “Maximal Strength Training”, which can be downloaded from the Canadian Athletics Coaching Centre at www.athleticscoaching.ca.

![Mathematics 321 2008–09 Exercises 5 [Due Friday January 30th.]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010730637_1-605d82659e8138195d07d944efcb6d99-300x300.png)