Drift & Conversion: Institutional Change in Political Science

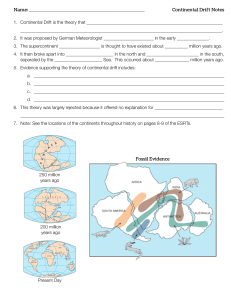

advertisement