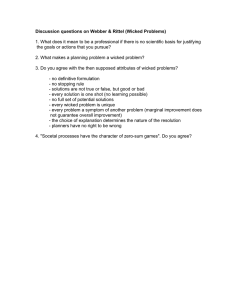

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289366161 Wicked problems: turning strategic management upside down Article in Journal of Business Strategy · January 2016 DOI: 10.1108/JBS-11-2014-0129 CITATIONS READS 20 5,891 2 authors, including: Charles Mcmillan York University 35 PUBLICATIONS 618 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Charles Mcmillan on 26 January 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. “Wicked Problems and the Misalignment of Strategic Management Design” Charles McMillan Schulich Business School, York University Toronto (charlesmcmillansgi@gmail.com) Jeffrey Overall Ryerson University Toronto (jsoverall@ryerson.ca) To Be Published in Journal of Business Strategy (Spring) 2015 January 2015 1 Introduction Most decision-makers know well the challenges of environment complexity. While the underlying causes are many, they include such factors as globalization of trade and finance, the digital revolution and the Internet, the explosion of education and income disparities. This new reality contains new forms of disorder, massive uncertainties and volatility, unpredictable consequences, and severe disruptions of the corporate playing field. How does society, in general, and strategic decision-makers in firms, universities, and public bureaucracies, in particular, address these very complex management discontinuities? Are strategy makers misaligning their internal decision structures to address ill-structured problems? The conventional doctrines of strategic management have, as their premise, the reduction and control of disequilibria, unknowns, and random events. They focus on various frameworks where the problems are known and understood, the means-end relationships are complicated but deterministic, knowledge and expertise can be applied by using formal mathematical models and conventional tools of linear analysis. The metrics of efficiency and effectiveness can address fluctuations and deviance from expected norms. In the past decades, corporate strategists, drawing on the huge academic literature, new models in the corporate space, military strategists and the consulting world have made great advances to address environmental uncertainty, knowledge complexity, and industry oscillations. Theories of creative destruction as the inevitable process of market economies, giving rise to new theories of disruptive technologies, Moore’s Law, and constant innovation, affect all sectors, even a once staid, insular industry like automobiles (Christensen, 1998; Schumpeter, 1942) 1 . These issues of knowledge complexity and problem uncertainties raise many challenges for corporate decision-makers. Do managers understand the appropriate tools to address unconventional problems? Or are they tied to conventional thinking, assumptions, and approaches to strategic decision-making? In their discourse, LaFlay and Martin (2013) describe how to approach this dilemma: (1) be clear about what business to operate in, (2) where to operate, (3) how to win, and; (4) what competencies are needed to consistently outperform the competition. This approach forms the core theories and models taught in business schools. As depicted in Figure 1, corporate strategy models now are more comprehensive, shifting the emphasis to include not just corporate positioning against competitors, but also encompassing people issues, network alignments, and the management of ideas and innovation in uncontested markets. 1 For over 100 years in the automotive industry, only three dramatic innovations occurred in 1904 (Ford’s system of mass production), 1956 (Toyota’s system of lean production), and hybrid vehicles in the 1990s. Since then, novelty and innovation occurs with the shift from ownership of vehicles to access to vehicle services (such as Uber, Zipcar, and RelayRides), new dealership models (Tesla selling directly to consumers), and new connectivity, such as vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication, semiautonomous and fully autonomous driving, or connecting to the cloud. 2 Figure 1 – Changing the Focus of Corporate Strategy The Four Ps of Strategy: 1970s – Price – Low Cost Leadership 1980s – Industry Position and Portfolio Analysis 1990s – Organizational Processes and Capabilities 2000 + - People, Networks, Sustainability Price: Cost Leadership Positioning Processes People Tools: Scale, Experience Curves, Cost Analysis, Industry structure and supply curves Tools: BCG Growth/ Share Matrix GE Matrix McKinsey 7s Scenarios Tools: Value Chain Quality – TQM Balanced Score Board Resource-Base Time Tools: Collaboration Strategic Alliances Networks Blue Ocean Cloud Computing Source: Authors Questions remain: are these tools the right strategic approaches needed for all markets, strategic problems, and firms? Consider the following quote, describing the aftermath of the 2008 Wall Street financial debacle (emphasis added): Its 20 minutes before 4 p.m. in London and currency traders' screens are blinking red and green. Some dealers have as many as 50 chat rooms crowded onto four monitors arrayed in front of them like shields. Messages from salespeople and clients appear, get pushed up by new ones and vanish from view. Orders are barked through squawk boxes. This is the closing ‘fix’, the thin slice of the day when foreign-exchange traders buy and sell billions of dollars of currency in the largely unregulated $5.3trillion-a-day foreign-exchange market, the biggest in the world by volume, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Their trades help set the benchmark WM/Reuters rates used to value more than $3.6 trillion of index funds held by pension holders, savers and money managers around the world. Now regulators from Bern to Washington are examining evidence first reported by Bloomberg News in June that a small group of senior traders at big banks had something else on their screens: details of each other's client orders. Sharing that information may have helped dealers at firms, including JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., UBS AG, and Barclays Plc, manipulate prices to maximize their own profits, according to five people with knowledge of the probes. 3 "This is a market where there is no law and people have turned a blind eye," said former U.S. Sen. Ted Kaufman, a Delaware Democrat who sponsored legislation in 2010 to shrink the largest U.S. banks. "We've been talking about banks being too big to fail. What’s almost as big a problem is banks too big to manage" (Vaughan, Finch, & Ivry, 2013, p. 1). Such media accounts typify massive inconsistencies between model assumptions – openness, competition, transparency, executive responsibility, and low risk – and the reality of decision premises, a form of hypocrisy between mission goals and actual behaviour. Most theories of strategic decision-making apply premises and assumptions of rational behaviour and stable systems. In finance and the world of banking, actual strategic behaviour differs wildly from the rational model of perfect competition, where all the variables are known, where information is free and available, and where computation of strategic choices and their consequences are examined in minute detail. Indeed, the real world of corporate finance is the exact opposite. More generally, strategic approaches to complex problems are misaligned with the problems themselves and potentially make firms ill-equipped to address wicked problems with simplistic approaches. In this paper, we focus on wicked problems as the decision environment for strategic management. Wicked problems cover such diverse topics as climate change, low costhealthcare, terrorism, security, extreme income disparity in a world of trade liberalization, inner city poverty, white collar crime, and cyber crime. Other management problems are numerous - the hidden and real cost of waste management, volatile global supply chains, moral hazards in financial markets, and the organizational ecosystems to provide social justice in an era of ethnic nationalism. These issues are challenging but rarely inflict high risks for corporate misdemeanours. Wicked problems often arise when companies are faced with the need to cope with constant change or to face new, unprecedented challenges. Camillus (2008, p. 101) elaborates: Wicked problems often crop up when organizations have to face constant change or unprecedented challenges. They occur in a social context; the greater the disagreement among stakeholders, the more wicked the problem. In fact, it’s the social complexity of wicked problems as much as their technical difficulties that make them tough to manage. Not all problems are wicked; confusion, discord, and a lack of progress are telltale signs that an issue might be wicked. The signals of wicked problems involve: complexity with conflicts arising from multiple but differing stakeholder views, social and attitudinal variables, varying sequential and simultaneous pressures and timelines, possible presence of ideological precocity, and lack of clarity on end-means relations. Very different approaches to address, understand, and cope with wicked problems are needed. 4 The New Paradigm: Wicked Problems Corporate finance issues and food supply products exemplify conventional problem solving. Assumptions of caveat emptor, where customers know and understand the products offered, and senior managers understand the causal impacts of product-market linkages illustrate the contrast between conventional problems and wicked problems and possible moral hazardous outcomes. Financial institutions in many countries defined their products on the premise that they are conventional, and the Wall Street crash shows that they are truly wicked problems. Rittel (1972) is often credited as the author of the term ‘wicked problems.’ However, Churchman (1967) used the term in a guest editorial of a special issue of Management Science. In this, he defined wicked problems as “a class of social system problems, which are ill-formulated; where the information is confusing; where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values; and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing (p. B142).” Wicked problems have various antecedents, are difficult to define, and when conventional solutions are applied to them, the consequences can be undesirable. Put differently, they are dynamically-complex, illstructured, problems that have highly uncertain causes and outcomes (Batie, 2008). Contrary to wicked problems, Simon (1973) provides an efficient summary of the characteristics of traditional, conventional problems: 1. Well-structured problems have norms of testing solutions with mechanical processes using numbers; 2. A clear means-ends pattern between the problem or goal state, and future states to be reached or considered as the solution state; 3. Knowledge application about the problem and problem states; 4. Clear accuracy of means-ends that govern the ‘external’ world; 5. Such conditions that allow practical amounts of computation and practical search processes. Individuals and firms address countless daily issues meeting the norms of conventional problems, where continuities, not discontinuities, determine decision deliberation and preferences. Such problems differ from wicked problems, as shown in Table 1, highlighting the contrasts between conventional problems and wicked problems. Wicked problems have characteristics that reach the headlines but most firms do not want to address, in part because they require fundamentally different assumptions, thought processes, and methods of solution. In the corporate world, problem-solving and strategy-making reflect the playful images of Machiavelli, deciding how managerial behaviour can shift corporate risk to the public sector (‘heads I win, tails you lose’), allowing possibilities to make the external world a captive stakeholder. Such strategy models reflect a desire for order, continuities, sequential attention of problem-solving procedures, and consistency of belief systems with decision preferences. In crisis, by contrast, organizational cohesion diminishes; ambiguities, false choices, and intelligence failures arise from deep uncertainty of future 5 Table 1 - Characteristics of Problems: Conventional vs. Wicked Problems Characteristics 1. Problems Conventional Clear definition of problem, unknown solutions Wicked No clear definition of problem – unknown and changing solutions 2. Thought processes Linear Complex systems 3. Time dimension Task completed when No time solution, politically problem solved determinate 4. Nature of knowledge Scientific solutions by Problem definition is expertise experts function of stakeholder views and perspectives 5. Outcomes Outcome is either true or Unknown outcome – may false, successful or be better, worse, or unsuccessful acceptable 6. Problem approach Scientific, knowledge Solutions are judgmental, protocols depending on stakeholder views 7. Problem characteristic Loose coupling Tight coupling 8. Solutions characteristic Cause and effect analysis Multiple feedback analyses 9. Value system Shared values of outcomes Values are in dispute, or in conflict Source: Adapted from Batie (2008) and based on Kreuter et al. (2004). actions predicated on low individual and organizational trust. As Katz and Kahn (1967, p. 188) put it, “… praise and blame have one set of means when they come from a trusted source and another when they stem from untrusted sources”. Individuals address conventional problems daily, often informed by habits, past experience, protocols, and routines. For example, a medical doctor undertaking a patient diagnosis combines her stock of knowledge from memory, her colleagues’ advice, and certain tools (e.g., blood tests) as the basis to prescribe medical treatment to find acceptable solutions. Managers, on the contrary, apply software tools, judgement, and forecasts to stock shelves with replenished inventory based on past, current, and expected sales. Strategies and heuristics, or rules of thumb, which allow decision-makers to search for solutions to conventional problems, may become inappropriate to address wicked problems. Strategic Nature of Wicked Problems In today’s complex world, tools of strategy, such as forecasting, SWOT analysis, competitive forces, lifecycle models, and portfolio and scenario analysis stem from assumptions, premises, and theories drawn mainly from microeconomics. Unfortunately, real world social systems displaying novelty, disruptive change, and social dynamics are not governed by stable, linear causal mechanisms. More specifically, the modern views 6 of strategic management suggest that models and expectations of linear approaches leading to ‘optimal’ decisions with premises of cause and effect. Put differently, strategy ‘A’ leads to structural outcome ‘B’ with optimal performance outcome ‘C’. It is then necessary to fold the two states, before and after, to show that the strategic tools and mechanisms causes or impact the target state, using varying assumptions are of limited value to real understandings of expected outcomes. Horn (1981), addressing wicked problems, contends that “… a social mess is a set of interrelated problems and other messes. Complexity—systems of systems—is among the factors that makes social messes so resistant to analysis and, more importantly, to resolution.” Ackoff (1974) contended that there are three categories of wicked problems: puzzles (well-defined with optimal solutions), problems (well-defined but no single solution), and messes (hard to formulate). In real life and in organizations of diverse kinds, the butterfly effect sows how nonlinearity usually results in unpredictable outcomes. Weather, the stock-market, human and environmental health, novel products or processes, NIMBY infrastructure pressures for firms, and sociopolitical adversary groups are examples of unpredictable, nonlinear systems. Traditional approaches using bureaucratic systems fail to address wicked problems because their uncertainty characteristics require collaboration that enhances intellectual knowledge diffusion, joint learning, and understanding how one issue can be a symptom of a related problem. Effective collaboration demands a shared consensus on the problem definition, which fosters commitment of alternative solutions, and understanding of feedback mechanisms and mean-ends relationships. There are several aspects associated with defining complex problems including recognizing that a problem exists, and a clear picture of the measurable and immeasurable uncertainties and risks. Wicked problems require a decision process of structuring and restructuring, in which solutions emerge only gradually through a process of defining external and internal constraints. How one defines the problem affects the attempts to solve it. In this definitional context, the concept of task environment is essential, and its analysis means that tasks possess characteristics which the initial state can be transformed to the goal state. Collaboration requires intellectual exercises and experiential learning to allow executives to learn and harness the collaborative skills necessary to address wicked problems. It is therefore most important to establish the choices that satisfy the requirements of a solution (Goel & Pirolli, 1992). Wicked problems are rarely dealt with in the C-suite, except perhaps only under extreme crisis. Conventional models ignore the extremely complex causal relations and feedback mechanisms. They apply to decision problems of relative stability, linearity, simple causal mechanisms in the environment and the classical, hierarchical information flows. These strategic frameworks may be highlighted with mathematical and technical virtuosity, but disguise the true nature of many problems, assumptions of probabilistic inferences, and the explanatory powers of feedback and underlying causes. Strategies often tolerate the organizational hypocrisy of stated ends and actual results. 7 Similarly, wicked problems are rarely addressed in the core MBA curriculum. As depicted in Figure 2, business strategy textbooks, case studies, models, and tools fostered by consulting firms and their in-house journals often ignore wicked problems. Even worse, they address wicked problems with solutions that apply only to problems with well-defined probabilistic solutions. Models of traditional problem-solving hierarchical decision-making fail to understand the complicated interdependencies of wicked problems. Why? Conventionally, organizations cultivate measures of self-sufficiency or closed-systems thinking. These approaches parallel the organizational decision processes well-known in supply chain management called the bullwhip effect, where problems elicit information distortion, weak demand signal false impressions from data flows, naïve or poor forecasting emits reliance on past routines. Decision command structures (McMillan, 2010) become misaligned, from distorted information intelligence, erratic decision processes, shifting participants, and misunderstanding problem definitions with problem solutions. Strategic misalignments arise when organizations use a decision-making system designed to address environmental uncertainties that assume linear models with limited cognitive complexity and computational deliberation. Indeed, the seeds of simple failure, leading to catastrophic failure, rest in organizational hierarchies where dominant coalitions – senior managers and boards – display false reactions, such as a confirmation bias, where executives overestimate how others accept their belief systems, and where core assumptions are not assessed (March & Olsen, 1966). High Figure 2 - Conventional MBA Curriculum and Wicked Problem Solving Low Level of Uncertainty Wicked Problems of Corporations & Society Problem Solving In Conventional MBA Curriculum Low Value Conflict High Source: Authors The second is an anchor bias, where evidence is quickly accepted that supports existing assumptions while contrary opinions are downplayed or rejected. In this way, hostility toward critics is heightened in the hierarchy (Roxburgh, 2003) especially if decisionmakers fail to produce real solutions and, as a result, dire unintended consequences occur. In crisis, shifting technologies and information uncertainty suggest that organizations 8 focus on ambiguities at all levels. In some quarters, studies of intractable problems lead to theories of chaos and complexity, where linear thinking precludes problem-solving on complex dynamic issues. These traditional processes can be fatal when addressing wicked problems. Managing Problem-Solving Models with Strategic Alignment How do wicked problems challenge the cognitive systems of conventional managerial behaviour? Sheer complexity, to be sure, but inexperience, novelty, and weak sensemaking constantly test the orientation of ill-structured problems and the design choices. Cognitive psychologists now understand that such sense-making leads to ambiguities of conflict resolution, with inherent biases to conflate numbers and measurement with importance. Understanding the nature of wicked problems, and appreciating approaches to address them, represent a strategic design challenge. Past experience and historical precedents may prejudge appropriate views of success, or even the people to address the issues. Clearly, deviations from the norm defy conventions of what is appropriate. Misalignment of managers’ sense-making or, in other words, the vital managerial capacity to recognize, understand, and interpret inherent complexity in the environment (Weick, 1979) can lead to costly and possibly catastrophic errors (see Figure 3). Figure 3 – Alignment of Problem-solving and Nature of Problems Nature of Problems Conventional Business Model Planning Misalignment of Problem-Solving and Wicked Problems Advanced Strategic Planning Alignment: Managing High Risk Problem Solving Low Risk Managerial SenseMaking High Risk Wicked Source: Authors These issues are especially evident in knowledge-intensive firms that are platformdependent. An organizational platform is a strategic design that configures people, technology, and coordination processes that combine the tightly-coupled rule features of machine bureaucracy (i.e., exploitation) with highly flexible, loosely-coupled organic features of exploration. Exploitation involves cultivating knowledge that is already accepted, while exploitation often takes precedence at the expense of exploration. The recent grounding of the Boeing-580 Dreamliner illustrates the new skill-sets needed to address the platform complexity of global ecosystems of supply chains, logistics and supply clusters. The contrast between 20th century models of loosely-coupled structures 9 and the complexity of and tightly-coupled systems challenges new approaches to problem-solving. As Dyer (1994, p. 176) suggests “…a tightly integrated production network, dedicating supplier assets to the customer, will virtually always outperform a loosely-coupled production network”. Systems design, often seen in platform engineering, show qualitatively novel features, away from deterministic and probabilistic (often called stochastic), where there is knowledge (or good estimates) of the probability distribution of future events to uncertain and emergent systems of massive absence of knowledge. Platforms function as an extended network value-chain under a generic organizational ecosystem umbrella, with intense interaction processes including parts and component suppliers and output distributors tailored to meet specific customer needs with variants within common structures. Platform organizations center flexible, mass customization models with high variety, speed, reduced lead-time, and high reliability (March & Olsen, 1966). The risks of strategic misalignment, based on executive attention focusing not only to the wrong issues but with a closed mindset to the nature of wicked problems, may seem obvious. Executive behaviour reflects coalition politics that allows senior managers to mold firm identity, competences, and problem attention by controlling communication tools, issue agendas, luxury goods, and promotion positions that preserve power and status (March & Olsen, 1966). In general, steady economic growth, often thanks to government policies that calibrate the economy and to rectify oscillations of long tailed outcomes, allow corporations the opportunity to retain traditional strategic management tools. However, today’s corporate landscape means that wicked problems are not addressed, and conventional approaches to problem-solving are in reality incremental adjustments. The result is potential misalignment of corporate approaches to strategy, and possible catastrophic failure from the full implications of ill-structured systems, even though it may take years to realize the full impacts. These transformations change the nature of corporate risk and risk assessment. The intensity of knowledge in the design and engineering of products and services – smart phones, hybrid vehicles, nuclear power plants, and aerospace products – illustrate new demands of risk management, because their design features increase risks of failure with potentially catastrophic consequences. Charles Perrow (1984), studying high risk organizations such as nuclear power plants, addresses two dimensions of wicked systems. The first is the degree of inter-active complexity, with the potential of deeply-rooted ignorance about how variables interact or can be foreseen, understood, or managed. The second is tight coupling, the design system of tight, procedural and sequential flows of each subsystem where the failure of one, with little buffering or redundancy, can result in catastrophic failure of the entire system. Variability coordination is, however, not a trivial activity and needs high-levels of training, collaborative decision-making, long-term perspectives, but if successful becomes very difficult to replicate. Toyota pioneered lean production, with its Tier 1 and Tier 2 supplier network, now widely applied in industries as diverse as healthcare and aircraft production (Tang & Zimmerman, 2009). Problems that are perceptual, or data 10 driven, start at the bottom of the human cognitive system. Problem-solving of illstructured problems, by contrast, start at the top of the cognitive system. Combining goaldirected to data-directed processing is linked to more knowledgeable expertise (Simon & Gilmartin, 1973). Without extreme conditions of training, expertise, and a culture of safety, platform models can fail precipitously (Vaughan, 1996). Conclusion Conventional strategy management models presume reasonable stability in the task environment, in the nature of the feedback mechanisms (e.g., information and social relations) and the organizational design features that weaken the interactions and direct participation of activities of those decision-makers who make strategic choices and those who are removed in time and space from direct organizational activities. Wicked problem solving removes a culture of denial, quick adaptation to simple failure, and short-term repairs to communications feedback. Wicked problem-solving is by temperament and time horizon, a multilayered, multitasked, organizational challenge, and requires fundamentally different mindsets for design and performance systems for senior executives. Organizational pathologies rest in executive action: pursuit of goals and objectives with a false sense of causation, feedback filters that exaggerate good news and restrict bad news, and actions that given only token measures to correct faulty design decisions and faulty decision processes, including more emphasis on vertical channels than horizontal task interdependencies. Indeed, wicked problems are a fact of life in a global world, changing profoundly the nature of strategic management, where management faces a deep paradox – an environment of unprecedented interdependence yet unpredictable forces of chaos and volatility, a landscape of wicked problems. Infectious diseases, terrorism, climate change, and social catastrophes such as tsunamis and earthquakes are everyday occurrences. Strategic management now faces the prospect of a dramatic shift, away from reasonable deterministic models to address uncertainty – the firm as a portfolio of industries and technologies, a collection of distinct businesses and decision problems – to a collection of wicked problems with indeterminate solutions. As governments are incapable of addressing guerilla warfare and terrorism using conventional military tactics, organizations are also unable to address wicked problems using the traditional tools of strategic management. Executive preferences impact signals of past actions, memory recall, and weak feedback mechanisms. Indeed, the study of wicked problems requires a new corporate mindset, new collaborative models to address them, and new corporate processes and executive training tools who increasingly have to address them. The status quo state of denial is ending and strategists now require a new, multidisciplined approach to address wicked problems. A focused attention and recognition of historical, social, and technological impacts, with new strategic methodologies are vital. New skill sets needed for wicked problem-solving must include tools and models of the conventional MBA curriculum. However, as once mighty brands like IBM, Coca-Cola, and McDonald’s illustrate, disruptive change is more than technological or financial. The corporate environment encompasses very complicated social and political dimensions 11 that are the characteristics of wicked problems where simple, linear, and deterministic models will not provide optimal or even acceptable outcomes. 12 References Ackoff, R. (1974), Systems, messes, and interactive planning: Redesigning the future, Wiley Publishing, New York, NY. Batie, A.S. (2008), “Wicked problems and applied economics”, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 90, pp. 1196-1191. Camillus, J.C. (2008), “Strategy as a wicked problem”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 86 No. 5, pp. 99-109. Christensen, C. (1998), The innovators dilemma. Harper Business, New York, NY. Churchman, C.W. (1967), “Wicked problems”. Management Science, Vol. 14, pp. B141142. Dyer, J.H. (1994), “Dedicated assets: Japan’s manufacturing edge”, Harvard Business Review. Vol. 72, pp. 174-181. Goel, V. and Pirolli, P. (1992), “The structure of design problem space”. Cognitive Science, Vol. 16, pp. 395-429. Horn, R. E. (1981), Trialectics: Toward a practical logic of unity. Information Resources, Inc., Lexington, MA. Katz, D. and Kahn, R.L. (1967), The social psychology of organizations. Wiley Publications, New York, NY. Kreuter, M.W. De Rosa, C. Howze, E.H. and Baldwin, G.T. (2004), “Understanding wicked problems: A key to advancing environmental health promotion”, Health Education & Behaviour, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 441-454. Lafay, A.G. and Martin, R.L. (2013), Playing to win: How strategy really works. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. March, J.G. and Olsen, J. (1966), Ambiguity and choice in organizations. Universitetsforig, Bergen. McMillan, C. (2010), “Five forces for effective leadership and innovation”, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 31, pp. 11-22. Perrow, C. (1984), Normal accidents: Living with high risk futures. Basic Books, New York, NY. Rittel, H. (1972), “On the planning crisis: Systems analysis of the ‘first and second generations”, Bedriftskonomen, Vol. 8. 13 Roxburgh, C. (2003), “Hidden flaws in strategy: Can insights from behavioural economics explain why good executives back bad strategies?”, McKinsey Quarterly (May 2003). Schumpeter, J.A. (1942), Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. Harper and Row, New York, NY. Simon, H.A. (1973), “The structure of ill-structured problems”. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 4, pp. 181-204. Simon, H.A. and Gilmartin, K. (1973), “A simulation of memory for chess positions”, Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 29-46. Tang, C.S. and Zimmerman, J.D. (2009), “Managing new product development and supply chain risks: The Boeing 787 case”. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, Vol. 10, pp. 74-86. Vaughan, D. (1996), “The Challenger launch decision: Risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA”, Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL. Vaughan, L. Finch, G. and Ivry, B. (2013), “Secret currency traders’ club devised biggest market’s rates”, Bloomberg News, December 19, pp. 1-2. Weick, K. (1979), The social psychology of organizing. Random House, New York, NY. 14 View publication stats