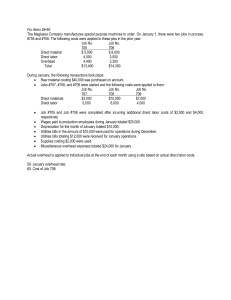

CHAPTER THREE JOB ORDER COSTING SYSTEM Introduction Accurate product costing is vital for business success. It is used for planning, product costing, cost control, and decision making. With a well setup product costing system, the price of products can be precisely determined. The product costing system can therefore be used by manufacturers to select products for maximum profitability. The following points need to be remembered in connection with costing systems: 1. The cost benefit approach: The costs of a complex costing system, including the costs of educating managers and other personnel to use it, can be high. Managers should install a more complex system only if they believe that its additional benefits - such as making better informed decisions - will outweigh the additional costs. 2. Costing systems should be tailored to the underlying operations; the operations should not be tailored to fit the costing systems. Any significant change in operations is likely to justify a corresponding change in the costing system. Designing the best system begins with a study of how operations are conducted and then determining from that study what information to gather and report. 3. Costing systems accumulate costs to facilitate decisions. Because it's not always possible to foresee specific decisions that might be necessary, costing systems are designed to fulfill several general needs of managers. Managers use product-costing information to make decisions and strategy, and for planning and control, cost management, and inventory valuation. 4. Costing systems are only one source of information for managers. When making decisions, managers combine information on costs with other non-cost information, such as personal observation of operations, and no financial performance measures, such as setup times, absentee rates, and number of customer complaints. Cost System Basics Cost system is a collective term for the policies, procedures, and functional hardware that a company uses to provide the value of the unit costs of its products or services. The cost system includes, but may not be limited to, the following components: cost objects; cost pools; cost accumulation method (e.g., job costing or process costing); cost measurement method (e.g., actual, normal, or standard costing); overhead allocation procedure (cost drivers, choice of capacity measure, and overhead rates) for service departments, joint process costs, and other overhead costs; cost reporting format (e.g., absorption or variable costing); hardware design (e.g., central mainframe or site workstations); accessibility (manager or financial analyst only or full accessibility); and reporting frequency. Organizations choose among costing systems by considering two things. First, how detailed and specialized must costs of each product be? Second, must periodic costs be accumulated from the beginning of the life of a product until it is sold? Answering these questions helps managers to choose from different types of costing systems. A cost object is any entity or activity for which costs are accumulated for management purposes (e.g., financial reporting, decision-making, or performance evaluation). Examples include physical products, service products (such as the processing of an insurance claim), customers, product lines, and organizational units. In any analysis of a cost system, it is important to consider whether the cost objects are appropriate for the decision(s) at hand. If the manager is interested in customer profitability, then the appropriate cost objects are individual customers. If the decision involves product mix, then products are the appropriate cost objects. If the decision involves outsourcing a service function, then the organizational unit that is the service department in question is the appropriate cost object. Cost pools are meaningful groups into which costs are aggregated. The most common cost pool is an organizational unit, such as a production or service department. Cost pools are intermediate accumulations of costs that help clarify the process of assigning and allocating costs to cost objects. Cost Pools can be production departments, service departments, or organizational activities. The costs 1 of the resources they consume are collected in each cost pool. Some are directly traced; others (such as service department costs in a manufacturing plant) may be allocated. Cost Objects (as it is discussed in CH-2) can be products, customers, services, or organizational units. Ideally, we assign costs to each cost object in proportion to the value of the resources they consume. Costs are transferred from cost pools to cost objects using cost drivers. Cost Drivers ideally reflect the indirect resources consumed in the production of a cost object. Traditional cost drivers include material costs, labor hours, and machine hours. These assume that production of cost objects consumes overhead costs such as set-ups, maintenance, engineering, quality control, etc., in proportion to production volume. Activity-based cost drivers, such as the number of set-ups or engineering change orders, assume that production of cost objects consumes overhead resources in proportion to the amount of a particular activity required. Cost Accumulation Method The cost accumulation method typically depends on the characteristics of the production process of the organization. The accumulation method describes the procedures by which costs are recorded as incurred, tracked with cost objects through the production process, and expensed when products are sold. It is possible to think of cost accumulation methods as lying along a spectrum: The next few paragraphs provide a brief description of these cost systems. Process Costing Process Costing is appropriate for production environments that involve high volumes of homogeneous products. Costs accumulated by department and are assigned to units of products by dividing the total costs incurred by the equivalent units of production. The equivalent unit concept accounts for the costs of beginning and ending work-in-process inventory. Examples of settings that might use process costing include chemical processing, oil refining, and paper production. Job Order (or Job) Costing What is Job-Order Costing? Job-order costing is used when different types of products, jobs, or batches are produced, typically over a rather short period of time to the customer's specifications. As a result, each job tends to be different. In job-order costing, each distinct batch of production is called a job or job order. The cost-accounting procedures are designed to assign costs to each job. Then the costs assigned to each job are averaged over the units of production in the job to obtain an average cost per unit. Examples of industries in which job-order costing is used include printing presses, construction, automobile repairs, office and household furniture, office machines, etc. In a job-order costing system, direct materials costs and direct labor costs are usually "traced" directly to jobs. Overhead is applied to jobs using a predetermined rate. Actual overhead costs are not "traced" to jobs. Remember that job costs consist of actual direct materials costs, actual direct labor costs, but applied overhead costs. Because reporting of business activity occurs periodically but completion of jobs generally does not occur at the end of a reporting period, job cost reporting must reflect the value of jobs at interim points before they are completed. There are two inventory accounts in which costs of jobs are accumulated. They are Work-in Process (WIP) inventory and Finished-goods inventory (FGI). Work-in-Process inventory accumulates all costs of resources used on jobs that have not been completed. Each job has its own subsidiary account, where costs specific to the job are recorded. Finished-goods inventory is an account where costs of all completed jobs are recorded. These costs are transferred from WIP inventory when a job is completed. The costs remain in FGI until the job is sold. Once sold, the costs of a job are transferred to an expense account called cost of goods sold. Companies using job costing usually have many jobs being worked on at the same time. An accounting system must allow the organization to keep track of all jobs separately and must maintain records of all jobs in progress, completed, and sold. It must also record activity for WIP inventory, FGI, and cost of goods sold. These three are general ledger accounts are important in a job costing system 2 The distinction between the job cost and the process cost methods centers largely on how product costing is accomplished. Job costing applies costs to specific jobs, which may consist of either a single physical unit or a few like units in a distinct batch or job lot. In contrast, process costing deals with great masses of like units and broad averages of unit costs. The basic distinction between job order costing and process costing is the breadth of the denominator: in job order costing, the denominator is small; however, in process costing, the denominator is large. Job costing and process costing are extremes along a continuum of potential costing systems. Each company designs its own accounting system to fit its underlying production activities. Some companies use hybrid costing systems, which are blends of ideas of both job costing and process costing. Job-costing System Process-costing system Distinct units of a product or service Masses of identical or similar units of a product or service Examples of Job Costing and Process Costing in the Service, merchandising, and Manufacturing Sector Service Sector Merchandising Sector Manufacturing Sector Job Costing Used -Auditing engagements -Consulting-firm engagements -Advertising-agency campaigns -Law cases -Auto-repair shops -sending special-order items by mail order -Special promotion of new store products -Aircraft assembly -House Construction Process Costing Used -Bank-check clearing -Postal delivery (standard items) -Grain dealer -Lumber dealer -Oil refining -Beverage production In this chapter, we focus on job costing systems. Chapter Four discusses process-costing systems. The discussion below assumes that a paper-based manual system is used for recording costs. Cost and other data are recorded on materials requisition forms, time tickets, and job cost sheets. Of course, many companies now enter cost and other data directly into computer databases and have dispensed with these paper documents. Nevertheless, the data residing in the computer typically consists of a "virtual" version of the manual system. Since a manual system is easy for students to understand, we continue to rely on it when describing a job-order costing system. 1. Job Cost Sheet. In a job order costing system, we maintain a job cost sheet for each job. The cost sheets are like the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger. While the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger provides a detailed listing of individual customer accounts, the job cost sheets show a detailed listing of the costs assigned to individual jobs in the work in process and finished goods inventories. Each job sheet breaks the costs down in terms of direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead assigned to individual jobs. The job cost sheet will have some code or descriptive data to identify the particular job and will contain spaces to collect costs of materials, labor, and overhead. 2. Accounting for materials Costs. When a job is started, materials that will be required to complete the job are withdrawn from the storeroom. The document that authorizes these withdrawals and that specifies the types and amounts of materials withdrawn is called the materials requisition form. Normally the production department supervisor completes the materials requisition form and presents it to the storeroom supervisor. The materials requisition form is prepared at least in three copies. One copy goes to the cost accounting department. In this department this copy is used as a basis for transferring the cost of the requisitioned material from the “Raw Material Inventory” account to the “Work in Process Inventory” account, 3 and for entering the cost of the material on the job-cost sheet for the production job in process. The materials requisition form identifies the job to which the materials are to be charged. Care must be taken when charging materials to distinguish between direct and indirect materials. For products and product components that are produced routinely, the required materials are known in advance. For these products and components, material requisitions are based on a “bill of material” that lists all of the materials needed. In complex manufacturing operations, in which production takes place in several stages, material requirements planning (MRP) may be used. MRP is an operations-management tool that assists managers in scheduling production in each stage of the manufacturing process. Such careful planning insures that, at each stage in the production process, the required subassemblies, components, or partially processed materials will be ready for the next stage. MRP system, which are generally computerized, include files that list all of the component parts and materials in inventory and all of the parts and materials needed in each stage of the production process. The cost of a manufactured product consists of the combined costs of the raw materials processed, the direct labor of employees who processed the raw materials and the factory overhead generated by the manufacturing process. Since materials may comprise the largest single element of cost, the control of materials cost is an important factor in manufacturing. Materials control Procedures The logical step-by-step development of materials control procedures can be illustrated by using a simplified version of what is ordinarily a complex manufacturing activity. Although the following presentation suggests that only one job is being processed and that each step in the processing of the forms described is isolated, the fact is that several jobs may be in production simultaneously, and the flow of paperwork would be continuous. Control during Purchasing On receipt of a customer’s order, the sales manager communicates to the production manager all the needed details, such as specifications, units ordered, required delivery date, and prices. From these data, the production manager reports a production order which authorizes the production of the required products. Bill of materials: The production order is given to supervisor in charge of production, who, based on knowledge of the product, prepares a schedule of the materials required to complete the order. The form for this purpose is called bill of materials. A copy of the bill of materials is sent to be storeroom keeper. This person checks the quantities of the various materials required with those on hand and on order to determine whether or not there are enough materials available to complete the order. If there are not enough materials, the purchasing agent must be notified of the quantity required; if there is an adequate amount of materials on hand for the order, it must be determined whether the withdrawal of the required quantity will reduce the stock on hand to a low level. If such is the case, the purchasing agent must be advised on the replacement needed. The bill of materials procedures are preliminary to the actual starting of the job order through the factory. They are designed to ensure that once the order starts into production, it will not be held up for lack of raw materials. Purchase Requisition. The form used by the storeroom keeper to notify the purchasing agent of the additional materials needed is known as a purchase requisition. This requisition is an important part of the materials control process because it is the agent’s authority to buy. A carefully designed form should be used. Purchase requisitions should originate with the storeroom keeper or some other designated individual given similar authority and responsibility. Purchase requisitions should be numbered serially to help detect the loss or misuse of any of these forms. They may be prepared in duplicate or in triplicate. If prepared in duplicate, the storeroom keeper retains one copy is sent to the purchasing agent. If the storeroom keeper has physical charge of the materials but another person in the accounting department is in charge of the subsidiary stores ledger in which a record is kept on the materials on hand, the requisition should be prepared in triplicate. The first copy goes to the purchasing agent; the second copy goes to the person in charge of the subsidiary stores ledger; and the third copy is retained by the storeroom keeper. 4 Purchase order The purchase requisition gives the purchasing agent authority to order the materials described in the requisition. From a file of quotations and prices, the vendor may be selected from whom the materials can be obtained at the lowest cost and with the least delay. If the file does not contain this information, the purchasing agent may communicate with several prospective vendors and request quotations on the materials needed. A purchase order is then completed and addressed to the chosen vendor, describing the materials wanted stating price and terms, and fixing the date and method of delivery. This purchase order should be numbered serially and prepared in quadruplicate. The first goes to the vendor, the second copy is retained by the purchasing agent, the third copy goes to the accounting department where it is referred to the stores ledger clerk, and the fourth copy goes to the receiving clerk. The stores ledger clerk makes a memo entry on the appropriate ledger sheet of the quantity on order. Vendor’s Invoice The vendor’s invoice should be received before the materials arrive at the factory. As soon as it is received, it goes to the purchasing agent, who compares it with the purchase order, noting particularly that the description of the items is the same, that the price and the terms agree, and that the method of shipment and the date of delivery conform to the instructions on the purchase order. When satisfied that the invoice is correct, the purchasing agent indicates approval directly on the invoice. Receiving Report It was suggested that the fourth copy of the purchase order goes to the receiving clerk to give advance notice of the arrival of the materials ordered. This is done to facilitate planning work and allotting space to incoming materials. The receiving clerk is in charge of the receiving department where all incoming materials are received, opened, counted or weighed, and tested for conformity with the order. If the materials received are of too technical a nature to be tested by the receiving clerk, the inspection may be undertaken by an engineer from the production manager’s office or the materials may be sent to the plant laboratory for testing. As the receiving clerk counts and identified the materials, a receiving report should be prepared similar in form to the one reproduced below. Each report is numbered serially and shows from whom the materials were received, when they were received, what the shipment contained, and the number of the purchase order that identifies the shipment. The report should be prepared in quadruplicate. The first and second copies go to the purchasing agent, the third copy goes with the materials or supplies to the storeroom keeper to ensure that all of the materials that come to the receiving department are put into the storeroom; and the fourth copy is retained by the receiving clerk. The purchasing agent’s first copy of the receiving report is compared with the vendor’s invoice and the purchase order to determine that the materials received are exactly like those ordered and billed. If they are found to be the same, the purchasing agent then attaches the receiving report to the other forms already in the file and sends the entire file to the accounting department where a voucher is prepared and recorded in the voucher register. To the second copy of the receiving report, the purchasing agent adds the unit prices of the articles received and extends the figure to show the total cost. This copy then goes to the accounting department for posting to the appropriate materials accounts in the stores ledger. The purpose of this double routing to the accounting department of copies of the same form is to maximize internal control procedures. One accounting clerk enters the purchase in total in the voucher register; a second clerk enters the purchase in detail in the subsidiary stores ledger. Debit-Credit Memorandum - occasionally, a shipment of materials does not match the order and the invoice. When this situation occurs, comparing the receiving report with the purchase order and the invoice will disclose the variance to the purchasing agent. Whatever the cause of the difference, it will lead to correspondence with the vendor, and copies of the letters should be a part of the files of forms relating to the transaction. If a larger quantity has been received than has been ordered and the excess is to be kept for future use, a credit memorandum is prepared notifying the vendor of the amount of the increase in the invoice. If, on the other hand, the shipment is short, one of the two courses of action may be taken. If the materials received can be used, they may be retained and a debit memorandum prepared notifying the vendor of the amount of the shortage. If the materials received can not be used, a return shipping order is prepared and the materials returned. 5 The return shipping order is usually made out in triplicate. The first copy goes to the vendor, the second copy goes to the receiving or shipping clerk, and the third copy is filed with other forms relating to the transaction. Debit or credit memorandums should be prepared in duplicate. The first copy goes to the vendor and the second copy is filed with documents relating with the transaction. Not until all variances or disagreements have been resolved will the transaction be complete. When they are resolved, the purchasing agent sends the file to the accounting department. Control During storage and Issuances The proceeding discussion applies to the control of materials during the process of procurement. The routine that has been suggested and the forms described have traced the ordering and the arrival of the materials and their transfer to the storeroom. The next problem to be considered is the storage and issuance of materials and supplies. Materials inventories usually represent a considerable investment of money; therefore, care should be taken to devise an adequate control system to protect these assets. The problem is how this control can best be achieved. The importance of knowing the quantities of materials on hand at any time has already been emphasized; it is equally important that the cost of materials on hand be known. Materials Requisition No material should be issued from the storeroom except on written authorization so that there is less chance of theft, carelessness, or misuse. The form used to provide this control is known as the material requisition or stores requisition and is prepared by the person or persons in the factory authorized to withdraw materials from the storeroom. The individuals who are authorized to perform this function may differ from company to company, but such authority must be given to someone. The most satisfactory arrangement would be to have the production manager prepare all of the materials requisitions, but this is not usually feasible. Another arrangement is to require that the supervisor of the department sign all materials requisitions. When a properly signed requisition is presented to the storeroom keeper, the requisitioned materials are released. The employee to whom materials are issued should be required to sign the requisition. The material requisition, which is numbered serially, is usually prepared in quadruplicate. The first and second copy goes to the accounting department. One copy, after pricing, provides the information needed in posting the cost of requisitioned materials to the appropriate accounts in the job cost and factory overhead ledgers. Direct materials are charged to the proper jobs and indirect materials are charged to the factory overhead accounts. The other copy provides the information needed in posting the quantities and costs of issued materials to the credit of the proper materials accounts in the stores ledger. This copy also serves as a source of the information needed in preparing a summary of the total direct and indirect materials issued during the month. The third copy is given to the storeroom keeper and serves as the authority for issuing the materials requisitioned. The fourth copy is retained by the production manager or supervisor who prepared it. Identification continues to be the most important factor in the control of materials. From the time materials are issued for use in the factory until they are removed as finished products, they are identified by number as applying to a particular job. For this reason, one of the most important items of information that should appear on the materials requisition is a job or production order number. 3. Accounting for Labor Costs. Labor costs are recorded on a document called a time ticket or a time sheet. Each employee records the amount of time he or she spends on each job and each task on a time ticket. The time ticket is the source document used in the cost accounting department as the basis for adding direct-labor cost to “Work in Process Inventory” and to the job-cost sheets for the various jobs in process. In some factories a computerized time-clock system may be used. Employees enter the time they begin and stop work on each job into the time clock. The time clock is connected to a computer, which records the time spent on various jobs and transmits the information to the accounting department. The time spent on a particular job is considered direct labor and its cost is "traced" to that job. The cost of time spent on other tasks, not traceable to any particular job, is usually considered part of manufacturing overhead. 6 Allocation of Factory Overhead Why Allocation? As discussed in the previous chapter, manufacturing overhead includes all of those costs incurred in the manufacturing process which are not directly "traced" to a particular cost object. In practice, manufacturing overhead usually consists of all manufacturing costs other than direct materials and direct labor. Compared to direct materials and direct labor, manufacturing overhead costs are not as easy to assign to particular job. Besides, for most overhead costs actual cost is known after a long period of time, say, after a year, a month, etc. So, since manufacturing overhead costs are also costs of a job, we assign (allocate) manufacturing overhead to jobs based on a predetermined overhead rate, which is estimated at the beginning of the year. Otherwise, we would have to wait until the end of the year to calculate the cost of jobs. Selection of Allocation Base In order to allocate overhead costs, some type of allocation base common to all products being produced must be identified. The most widely used allocation bases are direct labor-hours, direct labor costs, and machinehours. (These bases have been severely criticized in recent years since allegedly there is little relationship between machine-hours or direct labor-hours and overhead.). A predetermined overhead rate is computed by dividing the estimated total overhead for the upcoming period by the estimated total amount of the allocation base. Ideally overhead cost should be strictly proportional to the allocation base; in other words, for example a 10% change in the allocation base should cause a 10 % change in the overhead cost. Only then will the allocated overhead costs be useful in decision-making and in performance evaluation. However, much of the overhead typically consists of costs that are not proportional to any allocation base that could be devised for products and hence any scheme for allocating such costs will inevitably lead to costs that are biased and unreliable for decision-making and performance evaluation. In practice, the overriding concern is to select some bases for allocating all overhead costs and hardly any (scant) attention is paid to questions of causality. The predetermined cost-driver rate may be referred to as a predetermined overhead rate or a burden rate. Developing predetermined cost-driver rates requires a lot of estimation, described below. For estimating cost-driver rates, all activities must be defined and categorized. Then the overhead costs of all of the categories must be estimated. These cost estimates are usually based on past experience, current conditions, and expected changes. Next, cost-driver bases must be chosen and the quantity of the base must be estimated. Sometimes a cost-driver base is obvious for some overhead costs. At other times, a valid cost-driver base cannot be identified. Cause and effect relationship between the driver and the cost must be investigated. Finally, the predetermined cost-driver rate can be calculated by dividing the estimated cost of a resource by the estimated quantity of the chosen cost-driver base. These rates are then used to apply costs to jobs based on the actual amount of use of the cost driver. At any rate, the actual amount of the allocation base incurred by a job is recorded on the job cost sheet. The actual amount of the allocation base is then multiplied by the predetermined overhead rate to determine the amount of overhead that is applied to the job. The following bases can be used to compute the factory overhead application rate: 1. Physical output per unit of production base 2. Direct materials cost base 3. Direct labor (DL) cost base 4. Direct labor hours base 5. Machine hours base The bases used differ not only from company to company but also from one department or cost center to another within the same company. 1. Physical output per unit of production base This method applies factory overhead equally to each unit produced and is appropriate when a company or department manufactures only one type/kind of product. This method is very simple since data on the 7 units produced are readily available for applying factory overhead. The factory overhead rate is computed as follows: Factory overhead rate per unit of production = Estimated factory overhead costs Estimated units of production 2. Direct materials cost: If factory overhead consists mainly of the labor and equipment costs needed for material handling, a direct relationship is established and this base is used. A problem arises when more than one product is made, because each product requires its own quantities and types of materials, therefore accuracy would dictate a separate computation of factory overhead application rates for each product. This, however, violates the goal of simplicity. The factory overhead rate is computed as follows: FOH rate as a percentage of direct material cost = Estimated factory overhead cost X100% Estimated direct material costs This method has limited use because in most cases no logical relationship exists between direct material cost of a product and factory overhead used in its production. 3. Direct labor cost base: This is the most widely used base because direct labor costs are generally closely related to factory overhead costs and payroll data are readily available. It therefore meets the objectives of having a direct relationship to factory overhead cost, being simple to compute and apply and requiring little, if any, additional cost to compute. The formula is as follows: FOH rate as a percentage of direct cost = Estimated factory overhead cost X 100% Estimated direct labor cost This method would not be appropriate: a) If there is a direct relationship between factories overhead cost and direct labor cost but wage rates vary greatly within departments. b) If factory overhead costs are composed largely of depreciation and equipment related costs. 4. Direct labor hours: This method is appropriate when there is a direct relationship between factory overhead costs and direct labor hours and when there is significant disparity in hourly wage rates. Time keeping records must be accumulated to provide the data necessary for applying this rate. The rate computed as follows: Factory overhead rate per direct labor hours = Estimated factory overhead cost Estimated direct labor hours This method like direct labor cost method would be inappropriate if factory overhead cost were composed of costs unrelated to labor activity. 5. The machine hours: This method uses the time required for machines to perform similar operations as a base in computing the factory overhead application rate. This method is appropriate in organizations or departments that are largely automated so that the majority of factory overhead costs consist of department and other equipment related costs. The formula is as follows: Factory overhead rate per machine hours =Estimated factory overhead cost Estimated machine hours In general, Factory overhead application rate per unit\dollars = Estimated factory overhead costs Estimated base at denominator activity Note that in any case, the numerator remains constant; only the denominator or base activity varies. General Approach to Job Costing There are seven steps to assigning costs to an individual job. This seven-step procedure applies equally to assigning costs to a job in the manufacturing, merchandising, and service sectors. 8 Step 1: Identify the job that is the chosen cost Object. Step 2: Identify the Direct costs of the Job. Direct material and direct labor: Direct materials costs are calculated by multiplying the quantity of each material used for a particular job by its unit cost (the direct-cost rate) and adding together the costs of all the materials. Similarly, direct manufacturing labor costs are calculated by multiplying the hours worked by each employee on a particular job by his or her wage rate and adding these costs together. Step 3: Select the cost-Allocation Bases to Use for Allocating Indirect Costs to the Job. Indirect manufacturing costs are necessary costs to do a job that cannot be traced to a specific job. It would be impossible to complete a job without incurring indirect costs such as supervision, manufacturing engineering, utilities, and repairs. Because these costs cannot be traced to a specific job, they must be allocated to all jobs but not in a blanket way, different jobs require different quantities of indirect resources. The objective is to allocate the costs of indirect resources in a systematic way to their related jobs. Companies often use multiple cost-allocation bases to allocate indirect costs. Step 4: Identify the Indirect Costs Associated with Each Cost-Allocation Base: i.e. FOH. Step 5: Compute the Rate per Unit of Each cost-Allocation Base Used to Allocate Indirect costs to the Job. For each cost pool, the indirect-cost rate is calculated by dividing total overhead costs in the pool (determined in step 4 above) by the total quantity of the cost-allocation base (determined in step 3 above). Step 6: compute the Indirect costs Allocated to the Job. The indirect costs of a job are computed by multiplying the actual quantity of each different allocation base (one allocation base for each cost pool) associated with the job by the indirect cost rate of each allocation base. Step 7: Compute the Total Cost of the Job by Adding all direct and Indirect costs Assigned to the Job. Examples 1 1. The following budgeted data is given for XYZ Textile Factory for the year 2001. Estimated factory overhead for the year………………………………$450,000 Estimated number of shirts to be produced in the year…………………200,000 Estimated direct material cost for the year…………………………….$300,000 Estimated direct labor cost…………………………………………….$900,000 Estimated direct labor hours………….……………………………… 300,000 hrs Estimated machine hours……………………………………………… 90,000 hrs Instruction: Compute the predetermined factory overhead rate based on the following bases. A. Physical output method B. Direct materials cost base C. Direct labor cost base D. Direct labor hours base E. machine hours base Example-2 Assume all information in example 1 above and the following additional information: Actual data for job 201 is give is given below o Actual shirts completed for job 201………………2,000 shirts o Actual direct material cost used………………...$30,000 o Actual direct cost incurred……………………...$20,000 o Actual direct labor hours used…………………. 400 hours o Actual machine hours…………………………. 240 hours Instruction: Record the applied factory overhead and determine the total cost of job 201 under each of the five bases. A. Physical output method B. Direct materials cost base C. Direct labor cost base D. Direct labor hours base E. Machine hours base 9 The Manufacturing Overhead Control Account Actual overhead costs are recorded by debiting “Manufacturing Overhead Control” account. Overhead costs applied to jobs in Work in Process using predetermined rates are recorded on the credit side of the Manufacturing Overhead Applied account with a debit to ‘Work in Process’ account. Time Period Used To Compute Indirect-Cost Rates Indirect cost rates should be calculated for a long period of time (usually for a year) and not for short periods (such as a week, a month, etc). This is so because of the following reasons: 1. The numerator reason (indirect-cost pool). The shorter the period, the greater the influence of seasonal patterns on the amount of costs. For example, if indirect- cost rates were calculated each month, costs of heating (included in the numerator) would be charged only to production during the winter months. But an annual period incorporates the effect of all four seasons into a single, annual indirect-cost rate. Levels of total indirect costs are also affected by nonseasonal erratic costs. Examples of nonseasonal erratic costs include costs incurred in a particular month that benefit operations during future months, costs of repairs and maintenance of equipment, and costs of vacation and holiday pay. Pooling all indirect costs together over the course of a full year and calculating a single annual indirect-cost rate helps to smooth some of the erratic bumps in costs associated with specific periods. 2. The denominator reason (quantity of the allocation base). Another reason for longer periods is the need to spread monthly fixed indirect costs over fluctuating levels of monthly output. Some indirect costs may be variable each month with respect to the cost allocation base (for example, supplies). Whereas other indirect costs are fixed each month (for example, property, taxes, and rent). Normal Costing The difficulty of calculating actual indirect cost rates on a weekly or monthly basis means managers cannot calculate the actual costs of jobs as they are completed. However, managers want a close approximation of the manufacturing costs of various jobs regularly during the year, not just at the end of the year. Managers want manufacturing costs (and other costs, in fact) for ongoing uses, including pricing jobs, managing costs and preparing interim financial statements. Because of these benefits of immediate access to job costs, few companies wait until the actual manufacturing overhead is finally known (at year end) before allocating overhead costs to compute job costs. Instead, a predetermined or budgeted indirect-cost rate is calculated for each cost pool at the beginning of a fiscal year, and overhead costs are allocated to jobs as work progresses. For the numerator and denominator reasons already described, the budgeted indirect-cost rate is computed for each cost pool by dividing the budgeted annual indirect cost by the budgeted annual quantity of the cost allocation base. Using budgeted indirect-cost rates gives rise to normal costing. Normal costing is a costing method that traces direct costs to a cost object by using the actual direct-cost rates times the actual quantity of the direct cost inputs, and allocates indirect costs based on the budgeted indirect-cost rates times the actual quantity of the cost allocation base(s). Both actual costing and normal costing trace direct costs to jobs in the same way. The actual quantities and actual rates of direct materials and direct manufacturing labor used on a job are known from the source documents as the work is done. The only difference between actual costing and normal costing is that actual costing uses actual indirect-cost rates, whereas normal costing uses budgeted indirect-cost rates to cost jobs. Example-3 (taken from your text book, page 123, exercise 4-18) Anderso construction assembles residential houses. It uses a job costing system with two direct cost categories (direct materials and direct labor) and one indirect cost pool (assembly support). A direct labour hours is the allocation base for assembly support costs. In December 2003, Anderson budgets 2004 assembly support costs to be $8,000,000 and 2004 direct labor hours to be 160,000. At the end of 2004, Anderson is comparing the cost of several jobs that were started and completed in 2004. Laguna Model Mission Model Construction period Feb – June 2004 May – Oct 2004 Direct materials $106,450 $127,604 Direct labor $36,276 $41,410 Direct labor hours 900 1,010 10 Direct material and direct labor are paid for on a contract basis. The costs of each are known when direct materials are used or direct labor hours are worked. The 2004 actual assembly – support costs were $6,888,000, and actual direct labor hours were 164,000. Required: i) Compute the (a) budgeted and (b) actual indirect cost rates. Why do they differ? ii) What is the job cost of the Laguna Model and the Mission Model using: (a) Normal costing and (b) Actual costing iii) Why might Anderson construction prefer normal costing over actual costing? Example-4 Zigba Furniture is a furniture manufacturing firm that uses job order costing. The company’s inventory balances on January 1, the beginning of its fiscal year were as follows: Raw materials............................................. Br 40,000 Work in process......................................... 30,000 Finished goods ........................................... 60,000 The company applies overhead cost to jobs on the basis of machine-hours worked. For the current year, the company estimated that it would work 150,000 machine-hours and incur a manufacturing overhead cost of Br 900,000. The following transactions were recorded for the year: a. Raw materials were purchased on account, Br 820,000. b. Raw materials were requisitioned for use in production, Br 760,000 (Br 720,000 direct material and Br 40,000 indirect material). c. The following costs were incurred for employee services; direct labor Br 150,000: indirect labor Br 220,000; sales commission, Br 180,000; administrative salaries, Br 400,000. d. Sales travel costs were incurred, Br 34,000. e. Utility costs were incurred in the factory, Br 86,000. f. Advertising costs incurred; Br 360,000. g. Depreciation for the year, Br 700,000 (80% relates to factory operations and 20% to selling and administrative activities) h. Insurance expired during the year, Br 20,000 (70% relates to factory operations and the remaining 30% relates to selling and administrative activities) i. Manufacturing overhead was applied to production. Due to greater than expected demand for its products, the company worked 160,000 machine hours during the year. j. Goods costing Br 1,800,000 to manufacture, according to their job cost sheets, were completed during the year. k. Goods were sold on account to customers during the year at a total selling price of Br 3,000,000. The goods cost Br 1,740,000 to manufacture according to their job cost sheets. Instruction: Prepare journal entries to record the preceding transactions. Budgeted Indirect Costs and End-Of-Period Adjustments Since the predetermined overhead rate is based entirely on estimated data, there will almost always be a difference between the actual amount of overhead cost incurred and the amount of overhead cost that is applied to the Work In Process account. This difference is termed under applied or over applied overhead and can be determined by the comparing these two accounts. An under applied balance occurs when more overhead cost is actually incurred than is applied to the Work in Process account. An over applied balance results from applying more overhead to Work in Process than is actually incurred. In another word, when the total FOH Applied exceeds the FOH Control account the difference is over applied and when the total FOH Applied is lower than the FOH Control account the difference is under applied. Cause of under- and over applied overhead When a predetermined overhead rate is used, it is implicitly assumed that the overhead cost is variable with (i.e., proportional to) the allocation base. For example, if the predetermined overhead rate is Br 80 per direct labor-hour, it is implicitly assumed that the actual overhead costs will increase by Br 80 for each additional 11 direct labor-hour that is incurred. If, however, some of the overhead is fixed with respect to the allocation base, this will not happen and there will be a discrepancy between the actual total amount of the overhead and the overhead that is applied using the Br 80 rate. In addition, the actual total overhead can differ from the estimated total overhead because of poor controls over overhead spending or because of inability to accurately forecast overhead costs. Disposition of under- and over applied Overhead There are three approaches to dealing with an under- or over applied overhead balance in the accounts. (1) the adjusted allocation-rate approach, (2) the proration approach, and (3) the write-off to cost of goods sold approach. 1. Adjusted Allocation-Rate Approach The adjusted allocation-rate approach restates all overhead entries in the general ledger and subsidiary ledgers using actual cost rates rather than budgeted cost rates. First, the actual indirect-cost rate is computed at the end of the year. Then, the indirect costs allocated to every job during the year are recomputed using the actual indirect-cost rate (rather than the budgeted indirect-cost rate). Finally, end-of year closing entries are made. The result is that at year-end, every job-cost record and finished goods record - as well as the ending Work-in Process Control, Finished Goods Control, and Cost of Goods Sold accounts - accurately represents actual indirect costs incurred. The widespread adoption of computerized accounting systems has greatly reduced the cost of using the adjusted allocation-rate approach. The adjusted allocation-rate approach yields the benefits of both the timeliness and convenience of normal costing during the year and the accuracy of actual costing at the end of the year. Each individual job-cost record and the end-of-year account balances for inventories and cost of goods sold are adjusted to actual costs. After-the-fact analysis of actual profitability of individual jobs provides managers with accurate and useful insights for future decisions about job pricing, which jobs to emphasize, and ways to manage costs. 2. Proration Approach Proration spreads under allocated overhead or over allocated overhead among ending work in process, finished goods and cost of goods sold. Materials inventories are not allocated manufacturing overhead costs, so they are not included in this proration. Organizations should prorate under allocated or over allocated amounts on the basis of the total amount of manufacturing overhead allocated (before proration) in the ending balances of Work-in-Process Control, Finished Goods Control, and Cost of Goods Sold. However, in case such information is not available, the ending balances (before proration) of WIP, FGs and CGS accounts can be used for disposition of over or under applied overhead. 3. Write-Off to Cost of Goods sold Approach In this case, the total under allocated overhead or over allocated overhead is included in the current year's Cost of Goods Sold. The simplest approach is to close out the under- or over applied overhead to Cost of Goods Sold Choice among Approaches Which of these three approaches is the best one to use? In marketing this decision, managers should be guided by how the resulting information will be used. If managers intend to develop the most accurate record of individual job costs for profitability analysis purposes, the adjusted allocation-rate approach is preferred. If the purpose is confined to reporting the most accurate inventory and cost of goods sold figures in the financial statements, proration based on the manufacturing overhead-allocated component in the ending balances should be used because it adjusts the balances to what they would have been under actual costing. Note that the proration approach does not adjust individual job cost records. The write-off to Cost of Goods Sold is the simplest approach for dealing with under allocated or over allocated overhead. If the amount of under allocated or over allocated overheads is small -- in comparison to total operating income or some other measure of materiality -- the write-off to Cost of Goods Sold approach yields a good approximation to more accurate, but more complex, approaches. Modern companies are also becoming increasingly conscious of inventory control. Thus, quantities of inventories are lower than they were in earlier years, and Cost of Goods Sold tends to be higher in relation to the dollar amount of work-in12 process and finished goods inventories. Also, the inventory balances of job-costing companies are usually small because goods are often made in response to customer orders. Consequently, as is true in our Robinson example, writing off under allocated or over allocated overhead instead of prorating it is unlikely to cause significant distortions in financial statements. For all these reasons, the cost-benefit test would favor the simplest approach -- write-off to Cost of Goods Sold -- because the more complex attempts at accuracy represented by the other two approaches do not appear to provide sufficient additional useful information. The Effect of under- and over applied Overhead on Net Income If overhead is under applied, less overhead has been applied to inventory than has actually been incurred. Enough overhead must be applied retroactively to Cost of Goods Sold (and perhaps ending inventories) to eliminate this discrepancy. Since Cost of Goods Sold is increased, under applied overhead reduces net income. If overhead is over applied, more overhead has been applied to inventory than has actually been incurred. Enough overhead must be removed retroactively from Cost of Goods Sold (and perhaps ending inventories) to eliminate this discrepancy. Since Cost of Goods Sold is decreased, over applied overhead increases net income. The Flow of Costs in Job Order Costing The basic flow of costs in a job-order system begins by recording the costs of material, labor, and manufacturing overhead. Direct material and direct labor costs are debited to the Work in Process account. Any indirect material or indirect labor costs are debited to the Manufacturing Overhead Control account, along with any other actual manufacturing overhead costs incurred during the period. Manufacturing overhead is applied to Work In Process using the predetermined rate. The offsetting credit entry is to the Manufacturing Overhead control account. The cost of finished units is credited to Work In Process and debited to the Finished Goods inventory account. When units are sold, their costs are credited to Finished Goods and debited to Cost of Good Sold. Example 5 A Corporation uses a job-order cost system. The factory overhead rate estimated for the year 2001 was $8 per DL hrs. The inventory accounts had the following balances on December 1: Materials………………………………$7,000 Work-in-process (job 210)……………………….. 6,500 Finished Goods (job 209)………………. 7,000 During December, the following events occurred: a) Material purchased on account $18,000 b) Direct materials and factory supplies were issued as follows: Job 211………………………$4,500 Job 212……………………… 5,300 Job 213……………………… 6,200 Supplies (indirect materials)….1,800 c) The December direct labor costs were: Job 210…………………150 hrs at $ 6/hr……………………..$ 900 Job 211………………… 400 hrs at $6/hr…………………….. 2,400 Job 212 ………………... 350 hrs at $6/hr……………………...2,100 Job 213 …………………100 hrs at $6/hr ……………………... 600 Total 1,000 hrs $ 6000 d) Factory indirect labor for December was $2,400. e) Other overhead costs incurred during December: Utilities (paid in cash)…………………. $2,500 Factory depreciation………………..…… 1,000 Repairs and maintenance (Paid in cash)… 500 Total……………………..$4,000 f) Job 210, 211, and 212 were completed and transferred to finished goods inventory. g) Job 209 and 210 were sold on account for 120% of cost assumes perpetual inventory system. 13 Instruction:1. Journalize the above transactions. 2. Determine ending balance of all inventory accounts. 3. Determine the under or over applied overhead. Example 6 Consider the following ending balances of some accounts in B Company. Factory Overhead Control Factory Overhead Applied 326,000 Finished Goods 70,000 324,000 Cost of Good Sold 900,000 Work in process 30,000 The amounts of factory overhead applied included in different accounts are as follows: Account Factory overhead cost Cost of goods sold…………………………$ 275,400 Finished goods…………………………….. 32,400 Work in process…………………………… 16,200 Instruction: 1. Compute over or under applied. 2. Show the disposition and the necessary journal entries to account for under or over applied OH using: a).Proration Approach b). Write-Off to Cost of Goods sold Approach Example-7 ABC Furniture Company has two departments and the following data relate to the company for the year 2008. Inventory January 1, 2008 Direct material---------------------------------130,000 Work in process-------------------------------100,000 Finished goods---------------------------------80,000 Manufacturing overhead costs budgeted for the year in both departments is given below: Overhead item Department-A Department-B Indirect labor 500,000 820,000 Supplies 90,000 80,000 Utilities 220,000 150,000 Repairs 280,000 220,000 Supervision 260,000 430,000 Factory rent 190,000 150,000 Depreciation-Factory 320,000 210,000 Insurance and others 120,000 140,000 Total 1,980,000 2,200,000 Machine hours 180,000 Direct labor cost 4,400,000 Note: The company applies overhead using machine hours in department-A and direct labor cost in department-B. 14 Summary of actual events for the year is given below for both departments and for the company as follows: No. A B C D E F G H Items Direct material purchased Direct material requisitioned Direct labor cost incurred FOH incurred FOH Applied Cost of goods manufactured Sales Cost of goods sold Department-A Department-B 2,200,000 1,800,000 2,200,000 1,760,000 1,500,000 5,600,000 2,200,000 X Total 3,800,000 3,700,000 7,400,000 4,400,000 X 15,640,000 26,000,000 15,600,000 Required A. B. C. D. E. compute the budgeted overhead rates for both departments Compute the amount of machine hours actually worked in department-A Compute the factory overhead applied in department-B Record transactions A through H Is overhead under applied or over applied and by how much? Example-8 Alpha limited company produces office equipments in response to its customer’s orders. The company uses job costing system that has two direct cost categories (DM and DL) and one indirect cost category (OH). Overhead is allocated based on manufacturing labor costs. Budgeted data for a given period is given below: Direct labor cost-------------------------2,100,000 Manufacturing overhead--------------1,260,000 Additional information At the end of that year, two jobs X and Y were incomplete. Total direct labor and direct material for job X is $55,000 and $110,000 respectively and for job Y $195,000 and $210,000 respectively. Machine time for jobs X and Y are 1,435 and 3,235 hours respectively. Total manufacturing overhead incurred for the period is $1,000,000 and direct labor cost total $2,000,000 (100,000 direct labor hours) There were no beginning inventories and in addition to the ending work in process inventory, finished goods has an ending balance of $780,000 out of which $200,000 is direct labor cost. Total sales for the period is $11,200,000 and goods are sold at 140% of their cost and operating expense for the period is $2,200,000 Required A. What is the balance of W/P, F/G and CGS at the end of the period before adjustment? B. Compute the cost of goods manufactured C. Is overhead under or over applied and by how much? D. Prorate the under or over applied overhead among W/P, F/G and CGS based on I. Their ending balance before proration II. The FOH in each item before adjustment Items Ending Fraction Allocated FOH-in Fraction Allocated balance OH ending OH W/P 720,000 720/9,500 15,157.89 150,000 150/1,200 25,000 F/G 780,000 780/9,500 16,421.05 120,000 120/1,200 20,000 CGS 8000,000 8,000/9,500 168,421.06 930,000 930/1,200 155,000 Total 9,500,000 1,200,000 E. Prepare a partial income statement for the period ( use I in E) 15 Example-9 XYZ Company has two departments in one of its plants: Machining and assembly. Its job costing system has two direct cost categories (DM and DL) and two manufacturing overhead categories (Machining department OH allocated using machine hours and Assembly department overheads allocated using direct labor cost). The following is a budget for the year 2009: Items Machining department Assembly department Manufacturing overhead $1,800,000 $3,600,000 Direct labor cost 1,400,000 2,000,000 Machine hours 50,000 hrs 200,000 hrs Direct labor hours 100,000 hrs 200,000 hrs Required A. During the month of February, the job cost record of Job-494 contained the following Items Direct material used Direct labor cost Direct labor hours Machine hours Machining department $45,000 14,000 1,000 hrs 2,000 hrs Assembly department $70,000 15,000 1,500 hrs 1,000 hrs I. Compute the total overhead cost for job-494 II. Compute the total cost of the job B. At the end of the year the total actual manufacturing overhead cost was $2,100,000 in the Machining department and $3,700,000 in the Assembly department. Assume that 55,000 actual machine hours were used in the machining department and that direct labor cost of $2,200,000 was incurred in the Assembly department: Is overhead under or over applied and by how much? Example-10 Z Law firm uses job order costing with two direct cost categories ( professional partner labor and professional associate labor) and two indirect cost categories ( general support and secretarial support). Budgeted data for the company during a particular month is as follows: Direct cost categories Items No. of professionals Hours of billable time per professional per year Total compensation (average per professional Professional partner labor 5 1,600 Professional associate labor 20 1,600 $200,000 $80,000 Indirect cost categories Items Total cost Allocation base General support $1,800,000 Professional associate labor Secretarial support $400,000 Professional partner labor Required A. Compute the budgeted direct cost rates for professional partners and associate partners B. Compute the budgeted indirect cost rates for professional partners and associate partners C. The has been offered to give professional services to Company X and Y that requires the following resources: 16 Items X-Company Y-Company Professional partner labor 60 hrs 30 hrs Professional associate labor 40 hrs 120 hrs Compute the budgeted total cost of giving services to both companies Example-11 A corporation uses a job order costing system. The following items relate the work in process account of the company for the month of March. Work in process March 1---------------------------$12,000 Direct material----------------------------------------40,000 Direct labor--------------------------------------------30,000 FOH applied-------------------------------------------27,000 Cost of goods manufactured------------------------100,000 The corporation applied overhead using direct labor cost.job-232, the only job in process at the end of March, has been charged with FOH of $2,250. Required: Compute AR=27,000/30,000=0.9 A. The cost of the job still in process B. The direct material cost charged to job-232 Accounting For Spoilage, Re-Work and Scrap Generally, manufacturing operations cannot escape the occurrence of certain losses or output reduction due to scrap, spoilage, or defective work. Although sometimes these are the cost of doing good units, management and the entire personnel of an organization should cooperate to reduce such losses to a minimum. As long as they occur, however, they must be reported and controlled. Definition of terminologies Scrap Materials: are raw materials left over from the production process that cannot be put back into the production for the same purpose. However, they may be useful for different purpose or production process. Waste Materials: are parts of raw materials left over after production that has no further use or resale value. Sometimes cost may be incurred to dispose waste materials. Spoiled Units: are units that do not meet production standards and are either sold for their salvage value or discarded. Spoiled units have imperfections that cannot be economically corrected. They may be sold as items of inferior quality or “seconds”. Defective (rework) units: are units that do not meet production standards and must be further processed in order to be salable as good units. Such units have imperfections considered correctable because the market value of the corrected units will be greater than the total cost incurred for the units. Note: scrap is the by-product of the production of the primary product whereas spoiled and defective goods are not by-products but imperfections of the primary product. Types of Spoilage The key objectives in accounting for spoilage are determining the magnitude of the costs of spoilage and distinguishing between the costs of normal and abnormal spoilage. Normal Spoilage Normal Spoilage is spoilage that is an inherent result of the particular production process and arises even under efficient operating conditions. For a given production process, management must decide the rate of spoilage it is willing to accept as normal. Costs of normal spoilage are typically treated as component of the costs of good unit manufactured because good units cannot be made without the simultaneous appearance of spoiled units. Normal spoilage rates should be computed using total units completed as the base, not total actual units started in production. Because total units started also include any abnormal spoilage in addition to normal spoilage. Moreover, the normal spoilage is the amount of expected spoilage associated or related to the good units produced. 17 Abnormal Spoilage Abnormal Spoilage is spoilage that should not arise under efficient operating conditions. It is not an inherent result of the particular production process. Abnormal spoilage is regarded as avoidable and controllable. Line operators and other plant personnel can generally decrease abnormal spoilage by minimizing machine break downs, accidents and the like. Abnormal spoilage costs are written off as losses of the accounting period in which detection of the spoiled units occurs. Job Costing and Spoilage The concepts of normal and abnormal spoilage also apply to job-costing systems. Abnormal spoilage is usually regarded as controllable by the manager. Costs of abnormal spoilage are not considered as inventor able costs and are written off as costs of the period in which detection occurs. Normal Spoilage costs in jobcosting systems just as in process costing systems are inventor able costs, although managements are tolerating only small amounts of spoilage as normal. Spoilage is an important consideration in any production and cost related to planning and control decision. Since in most cases spoilage is unavoidable, management must determine the most efficient production process that will keep spoilage to a minimum possible. When assigning costs, job-costing systems generally distinguish between normal spoilage attributable to a specific job and normal spoilage common to all jobs. Generally, as it is mentioned above in this chapter, spoilage is classified into two: normal and abnormal. 1. Normal spoilage: Is spoilage that results despite efficient production method. The costs of normal spoilage are considered to be unavoidable cost of producing good units and are therefore treated as a product cost. Normal spoilage costs are accounted for in two ways: Applied to a specific job Applied to all jobs Normal spoilages are recorded in an asset account like “Spoiled Goods Inventory” account. 2. Abnormal spoilage: Is spoilage in excess of what is considered normal for a particular production process. The total cost of abnormal spoilage should be charged to an expense account like “Loss from Abnormal Spoilage” account. Example-1 Assume that in ABC Company 10,000 units were put into production for job 09. The total cost of production was $ 300,000. Normal spoilage for the job is estimated to be 50 units. At the completion of production only 9,910 units were good. All spoiled units are estimated to have a salvage value of $5 each. Required: 1. Present the required journal entry assuming normal spoilage isA. Applied to a specific job B. Applied to all jobs 2. Compute the unit cost of the remaining finished good units. Solution To record normal spoilage: a) To specific job Spoiled Goods Inventory…………250 WIP-job 09…….…………………….250 b) To all jobs: Spoiled Goods Inventory…………250 FOH- Control…………………….1, 250 WIP- job 09……..……………….1, 500 To record abnormal spoilage: Spoiled goods inventory...……….200 18 Loss from Abnormal Spoilage……1,000 WIP-job 09…................................... 1,200 Example-2 In a Machine Shop 5 aircraft parts out of a job lot of 50 aircrafts parts are spoiled. Costs assigned prior to inspection point are $2,000 per part. The current disposal price of the spoiled parts is estimated to be $600 per part. When the spoilage is detected, the spoiled goods are inventoried at $600 per part. Normal Spoilage attributable to a specific job: Materials Control (5*$600) 30001 Work-in Process Control (specific job) (5*$600) 3000 Note that the Work-in Process Control (specific job) has already been debited $10,000 for the spoiled parts (5 spoiled parts * $2,000 per part). The effect of the $3,000 entry is that the net cost of the normal spoilage, $7,000 ($10,000-$3,000) becomes an additional cost of the 45(50-5) good units produced. The total cost of the 45 good units is $97,000. $90,000 (45units*$2,000 per unit) incurred to produce the good units plus the $7,000 net cost of normal spoilage. Normal Spoilage common to all jobs Materials Control (spoiled goods at disposal value 5*$600) MOH Control (normal spoilage $10,000-$3,000) Work-in Process Control (specific job 5*$2,000) 3000 7000 10000 Abnormal Spoilage: Materials Control (spoiled goods at current disposal value: Loss from Abnormal Spoilage Work-in Process Control (specific job) 3000 7000 10000 Accounting for defective (rework) units As with spoiled units, defective units are classified as either normal or abnormal. Normal defective units: The numbers of defective units in any particular production process that can be expected despite efficient operations are known as normal defective units. Normal defective rework costs may be: A) Applied to a specific job. B) Applied to all jobs. Abnormal defective units: The number of defective units in excess of what is considered to be normal for an efficient productive operation is called abnormal defective units. The total cost of reworking abnormal defective units should be charged to “Loss from Abnormal Defective” Account. Example-1 Assume that 40,000 units are placed into production for job 10. Normal defective units for this job are estimated to be 400 whereas actual defective units were 1000.The total cost to rework the 1000 defective units was as follows: Per unit Direct materials…………..$500……$0.50 Direct labor………………..1000……1.00 FOH-applied……………… 500…….0.50 $2000 $2.00 Required: Present the required entry assuming that normal rework costs are applied to a. A specific job b. All jobs 19 Solution Abnormal defective = total defective –normal defective. =1000 units –400 units = 600 units To record normal defective A) To specific job WIP-job 10 (400x Br 2)……………….800 Materials (400x0.5)………....................200 Payroll (400x0.1)………………….…...400 FOH-Applied……….…………...…….200 B) To all jobs FOH-control………………………..800 Materials…………….……………...200 Payroll……………………………..400 FOH-Applied………….……………200 To record abnormal Defectives: Loss from Abnormal Defects (600x$2)………..1,200 Material (600x0.5)………………………………..300 Payroll (600x1)……………………………………600 FOH-Applied (600x0.5)…………………………..300 A compound entry can also be made a) WIP-Job 10………………………………..800 Loss from Abnormal Defectives…………1,200 Materials………………………………… 500 Payroll………………………….…….…. 1,000 FOH-Applied…….…………………………500 b) FOH- control……………….……….. 800 Loss from defects……….………….. 1,200 Materials ………………….……………. 500 Payroll …………………………………….1, 000 FOH-Applied……………………………....500 Example-2 Consider Hull Machine Shop; assume that the 5 spoiled parts used in the illustration are reworked. The journal entry for the $10,000 of total cost assigned to the 5 spoiled units before considering rework costs are as follows: Work-in Process Control (Specific Job) 10000 Materials Control 4000 Wage payable Control 4000 MOH Allocated 2000 Normal Rework common to all jobs: MOH Control (rework costs) 3800 Materials Control 800 Wage payable control 2000 MOH Allocated 1000 20 Abnormal rework: Loss from Abnormal Rework 3800 Materials Control 800 Wage Payable Control 2000 MOH Allocated 1000 Accounting for Scrap Materials As for spoilage and defective units, the cost accounting system should provide a method of costing and control for scrap. When the amount of scrap produced exceeds the norm it could be an indicator of inefficiency. When the scarp value is small no entry is made until the scarp is sold. At the time the scarp is sold the following entry will be made: Cash (A/R)…… …….xxx Scrap Revenue/WIP/FOH-con……………..xxx The income from scrap sales is usually reported as “Other Income” in the income statement. When the value of the scarp is relatively high an inventory card will be prepared and if both the quantity and the market value of the scrap are known, the following journal entries are made. To record the inventory: Scrap Materials………………………..xxx Scrap Revenue /WIP / FOH-ctrl…………..xxx When the scrap is sold: Cash (A/R)…………………xxx Scrap Materials………………….xxx Note: 1. Sometimes scrap may be sold for more or less than the value at which it is recorded. Any difference between the sales price and the recorded value is treated as an adjustment to the account that was originally credited. (i.e., WIP, FOH- control, Scrap Revenue, Miscellaneous income, etc) 2. If the market value of the scrap is not known, no journal entry is made until the scrap is sold. At the time of sale, the following entry is made: Cash…………….……………………..xxx Scrap Revenue (WIP or FOH-ctrl)…………..xxx Example Bisrat Teshome Company maintains a Scrap Inventory account for metal scrap recovered from operations in the cutting department. On September 8, 2005 5,300 pounds of scrap with an estimated market value of $2,385 are transferred from the Factory to the storeroom. Instruction: make journal entries to record 1. The storage of the metal scrap. (Credit WIP account) 2. The cash sale of 1,900 pounds of scrap at recorded value. 3. The sale of 2,100 pounds of scrap at $0.52 per pound on credit. 4. The sale of 1,300 pounds of scrap at $ 0.39 per pound on credit. Solution 1. Scrap Material……………..2,385 WIP…………………………….2, 385 2. Cash……………………….855 Scrap Materials……………855 3. A/R……………………..1,092 Scrap Material………………945 WIP…………………………147 4. A/R……………………507 WIP…………………....78 Scrap Material……………585 21