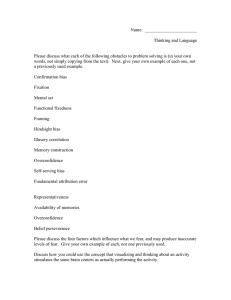

FINANCE Behavioral finance and wealth management building optimal

advertisement