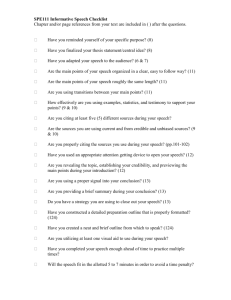

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

LABOR LAW

CANONICAL DOCTRINES

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES

TOPIC

Presumption of

Inherent

Inequality

DOCTRINE

The presumption is that the employer

and the employee are on unequal

footing so the State has the

responsibility to protect the employee.

This presumption, however, must be

taken on a case-to-case basis.

CITED IN

Perfecto

M.

Pascua v. Bank

Wise, Inc.

G.R. No. 191460 |

Jan. 31, 2018

CITING

Fuji

Television

Network,

Inc.

v.

Arlene Espiritu, G.R.

No. 204944-45, Dec.

3,

2014;

citing

Jaculbe v. Silliman

University, G.R. No.

156934, Mar. 16,

2007, citing Mercury

Drug Co, Inc. v. CIR,

G.R. No. L-23357,

Apr. 30, 1974; &

Philippine

Association

of

Service Exporters v.

Drilon,

G.R.

No.

81958, June 30, 1988

RECRUITMENT AND PLACEMENT

TOPIC

POEAStandard

Employment

Contract

integrated in

every

employment

contract

DOCTRINE

As part of a seafarer's deployment for

overseas work, he and the vessel

owner or its representative local

manning agency are required to

execute the POEA-SEC. Containing

the standard terms and conditions of

seafarers' employment, the POEASEC is deemed included in their

contracts of employment in foreign

ocean-going vessels.

CITED IN

Sharpe

Sea

Personnel, Inc. v.

Mabunay, Jr.

Estafa vs. Illegal

Recruitment

It is well-established in jurisprudence

that a person may be charged and

convicted for both illegal recruitment

and estafa.The reason therefor is not

hard to discern: illegal recruitment is

malum prohibitum,while estafa is

mala in se.In the first, the criminal

intent of the accused is not necessary

for conviction. In the second, such

intent is imperative. Estafa under

People v. Racho y

Somera

Page 1 of 16

abon3298

G.R. No. 206113 |

Nov. 6, 2017

G.R. No. 227505 |

Oct. 2, 2017

CITING

Wallem

Maritime

Services,

Inc.

v.

Tanawan, G.R. No.

160444, Aug. 29,

2012; citing Coastal

Safeway

Marine

Services,

Inc.

v.

Delgado, G.R. No.

168210, June 17,

2008; citing Pentagon

International

Shipping,

Inc. v.

Adelantar, G.R. No.

157373, July 27,

2004

People v. Chua, G.R.

No. 187052, Sept. 13,

2012; citing People v.

Chua,

G.R.

No.

184058, Mar. 10,

2010; citing People v.

Comila, G.R. No.

171448, Feb. 28,

2007; citing People v.

Hernandez, G.R. No.

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

Article 315, paragraph 2 (a) of the

Revised Penal Code is committed by

any person who defrauds another by

using fictitious name, or falsely

pretends to possess power, influence,

qualifications,

property,

credit,

agency, business or imaginary

transactions, or by means of similar

deceits executed prior to or

simultaneously with the commission

of fraud.

141221-36, Mar. 7,

2002; citing People v.

Sagaydo, G.R. No.

124671-75, Sept. 29,

2000 & People v.

Banzales, G.R. No.

132289, Jul. 18, 2000

LABOR STANDARDS

TOPIC

Designation as

"manager" not

enough to be

considered

managerial

employee

DOCTRINE

Managerial employees are ranked as

Top Managers, Middle Managers and

First Line Managers. The mere fact

that an employee is designated

"manager" does not ipso facto make

him one-designation should be

reconciled with the actual job

description of the employee for it is the

job description that determines the

nature of employment.

CITED IN

Asia

Pacific

Chartering (Phils.)

Inc. v. Farolan

Field Personnel

The definition of a "field personnel" is

not merely concerned with the

location where the employee regularly

performs his duties but also with the

fact that the employee's performance

is unsupervised by the employer. We

held that field personnel are those

who regularly perform their duties

away from the principal place of

business of the employer and whose

actual hours of work in the field cannot

be determined with reasonable

certainty. Thus, in order to determine

whether an employee is a field

employee, it is also necessary to

ascertain if actual hours of work in the

field can be determined with

reasonable certainty by the employer.

In so doing, an inquiry must be made

as to whether or not the employee's

time and performance are constantly

supervised by the employer.

If there is no work performed by the

employee, there can be no wage.

Far

East

Agricultural

Supply, Inc. v.

Lebatique

No-work-no-pay

Page 2 of 16

abon3298

G.R. No. 151370 |

Dec. 4, 2002

CITING

Paper

Industries

Corp. v. Laguesma,

G.R. No. 101738,

April 12, 2000; citing

Dunlop

Slazenger

(Phils.),

INC.,

v.

Secretary of Labor,

G.R. No. 131248,

Dec. 11, 1998; citing

Engineering

Equipment, Inc. v.

NLRC, G.R. No. L59221, Dec. 26, 1984

Auto Bus Transport

Systems v. Bautista,

G.R. No. 156367,

May 16, 2005

G.R. No. 162813 |

Feb. 12, 2007

Coca-Cola

Bottlers,

Phils.,

Inc. v. Iloilo CocaCola

Plant

Employees Labor

Union

Aklan

Electric

Cooperative Inc. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

121439, Jan. 25,

2000; citing Caltex

Refinery Employees

Association

v.

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

G.R. No. 195297 |

Dec. 5, 2018

Inclusion of

commission in

basic salary

Civil Code

exemption

against

garnishment

only refers to

It is well-established in jurisprudence

that the determination of whether or

not a commission forms part of the

basic salary depends upon the

circumstances or conditions for its

payment. In Phil Duplicators, Inc. v.

NLRC,

the

Court

held

that

commissions earned by salesmen

form part of their basic salary. The

salesmen's commissions, comprising

a pre-determined percentage of the

selling price of the goods sold by each

salesman, were properly included in

the term basic salary for purposes of

computing the 13th month pay. The

salesmen's commissions are not

overtime payments, nor profit-sharing

payments nor any other fringe benefit,

but a portion of the salary structure

which represents an automatic

increment to the monetary value

initially assigned to each unit of work

rendered by a salesman. On the other

hand, in Boie-Takeda Chemicals, Inc.

v. De la Serna, the so-called

commissions paid to or received by

medical

representatives

were

excluded from the term basic salary

because these were paid to the

medical representatives and rankand-file employees as productivity

bonuses, which were generally tied to

the productivity, or capacity for

revenue production, of a corporation

and such bonuses closely resemble

profit-sharing payments and had no

clear direct or necessary relation to

the amount of work actually done by

each individual employee.

The exemption under Article 1708

('The laborer's wages shall not be

subject to execution or attachment,

except for debts incurred for food,

shelter,

clothing

and

medical

attendance') of the Civil Code favors

Page 3 of 16

abon3298

Philippine Spring

Water Resources,

Inc. v. Court of

Appeals

G.R. No. 205278 |

June 11, 2014

Spouses

Balanoba

Madriaga

v.

G.R. No. 160109 |

Nov. 22, 2005

Brillantes, G.R. No.

123782, Sept. 16,

1997; citing Social

Security System vs.

SSS

Supervisors'

Union, G.R. No. L31832, October 23,

1982; citing J .P.

Heilbronn Co. vs.

National Labor Union,

G.R. No. L-5121, Jan.

30, 1953

Philippine

Duplicators, Inc. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

110068, Feb. 15,

1995,

and

BoieTakeda Chemicals,

Inc. v. De la Serna,

G.R. No. 92174, Dec.

10, 1993

Gaa v. CA, G.R. No.

L-44169, Dec. 3,

1985

U.P LAW BOC

"wages" not

"salaries"

Elements of

Wage Distortion

abon3298

only laboring men or women whose

work is manual. Belonging to this

class are the workers who usually

look to the reward of a day's labor for

immediate or present support. They,

more than any other persons, are the

ones in need of the exemption 27

which, needless to say, does not

encompass any and all workers.

Prubankers Association v. Prudential

Bank and Trust Company laid down

the four elements of wage distortion,

to wit: (1) an existing hierarchy of

positions with corresponding salary

rates; (2) a significant change in the

salary rate of a lower pay class

without a concomitant increase in the

salary rate of a higher one; (3) the

elimination of the distinction between

the two levels; and (4) the existence

of the distortion in the same region of

the country.

LABOR LAW

Philippine

Geothermal, Inc.

Employees Union

v.

Chevron

Geothermal Phils.

Holdings, Inc.

Prubankers

Association

v.

Prudential Bank &

Trust Co., G.R. No.

131247, Jan. 25,

1999

G.R. No. 207252 |

Jan. 24, 2018

POST-EMPLOYMENT

TOPIC

Test to

determine

employeremployee

relationship

DOCTRINE

The tests for determining employeremployee relationship are: (a) the

selection and engagement of the

employee; (b) the payment of wages;

(c) the power of dismissal; and (d) the

employer's power to control the

employee with respect to the means

and methods by which the work is to

be accomplished. The last is called the

"control test," the most important

element.

CITED IN

Tesoro v. Metro

Manila Retreaders,

Inc.

Determination

of "regular"

employee

There are two separate instances

whereby it can be determined that an

employment is regular: (1) if the

particular activity performed by the

employee is necessary or desirable in

the usual business or trade of the

employer; and, (2) if the employee has

been performing the job for at least a

year.

Once a project or work pool employee

has been: (1) continuously, as

opposed to intermittently, rehired by

the same employer for the same tasks

or nature of tasks; and (2) these tasks

are

vital,

necessary,

and

indispensable to the usual business or

trade of the employer, then the

employee must be deemed a regular

employee.

Pangilinan

v.

General

Milling

Corp.

Project

Employee

Attaining Status

of Regular

Employee;

Requisites

Page 4 of 16

abon3298

G.R. No. 171482 |

March 12, 2014

G.R. No. 149329 |

July 12, 2004

Freyssinet

Filipinas Corp. v.

Lapuz

G.R. No. 226722 |

March 18, 2019

CITING

"Brotherhood" Labor

Unity Movement v.

Zamora, G.R. No. L48645, Jan. 7, 1987;

citing

Investment

Planning Corp. of the

Phil. v. SSS, G.R. No.

L-19124, Nov. 18,

1967,

Manfinco

Trading Corp. v.

Ople, G.R. No. L37790, Mar. 25, 1976

Viernes v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 108405,

April 4, 2003; citing

De Leon v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 70705, Aug,

21, 1989 & Abasolo v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

118475, Nov. 29,

2000

Maraguinot, Jr. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

120969, Jan. 22,

1998; citing PNCC v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

85323, June 20, 1989

& Capitol Industrial

Construction Groups

v. NLRC, G.R. No.

U.P LAW BOC

Valid Project

Employment

Test to

determine

project

employment

Fixed-term

employment;

when valid

abon3298

The Court has upheld the validity of a

project-based contract of employment

provided that the period was agreed

upon knowingly and voluntarily by the

parties, without any force, duress or

improper pressure being brought to

bear upon the employee and absent

any other circumstances vitiating his

consent; or where it satisfactorily

appears that the employer and

employee dealt with each other on

more or less equal terms with no moral

dominance whatever being exercised

by the former over the latter; and it is

apparent from the circumstances that

the period was not imposed to

preclude the acquisition of tenurial

security by the employee.

According to jurisprudence, the

principal test for determining whether

particular employees are properly

characterized as "project employees"

as

distinguished

from

"regular

employees," is whether or not the

employees were assigned to carry out

a "specific project or undertaking," the

duration (and scope) of which were

specified at the time they were

engaged for that project. The project

could either be (1) a particular job or

undertaking that is within the regular or

usual business of the employer

company, but which is distinct and

separate, and identifiable as such,

from the other undertakings of the

company; or (2) a particular job or

undertaking that is not within the

regular business of the corporation. In

order to safeguard the rights of

workers against the arbitrary use of the

word "project" to prevent employees

from attaining a regular status,

employers claiming that their workers

are project employees should not only

prove that the duration and scope of

the employment was specified at the

time they were engaged, but also that

there was indeed a project.

A fixed-term employment is valid only

under certain circumstances. We thus

laid down in Brent School, Inc. v.

Zamora parameters or criteria under

which a "term employment" cannot be

said to be in circumvention of the law

on security of tenure, namely:

Page 5 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

E. Ganzon, Inc. v.

Ando, Jr.

G.R. No. 214183 |

Feb. 20, 2017

Omni

Hauling

Services, Inc. v.

Bon

G.R. No. 199388 |

Sept. 3, 2014

Regala v. Manila

Hotel Corp.

G.R. No. 204684,

Oct. 5, 2020

105359, April 22,

1993;

Salinas, Jr. v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 114671,

Nov. 24, 1999; citing

Caramol v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 102973,

Aug. 24, 1993

GMA Network v.

Pabriga, G.R. No.

176419, Nov. 27,

2013; citing ALUTUCP v. NLRC, G.R.

No. 109902, Aug. 2,

1994

Brent School, Inc. v.

Zamora, G.R. No. L48494, Feb. 5, 1990

U.P LAW BOC

Regular

seasonal

employment

Requirements

of employer in

probationary

employment

Penalty

imposed should

be

commensurate

to infraction

abon3298

1) The fixed period of employment

was knowingly and voluntarily

agreed upon by the parties without

any force, duress, or improper

pressure being brought to bear

upon the employee and absent

any other circumstances vitiating

his consent; or

2) It satisfactorily appears that the

employer and the employee dealt

with each other on more or less

equal terms with no moral

dominance exercised by the

former or the latter.

As with project employment, although

the

seasonal

employment

arrangement involves work that is

seasonal or periodic in nature, the

employment itself is not automatically

considered seasonal so as to prevent

the employee from attaining regular

status. To exclude the asserted

"seasonal" employee from those

classified as regular employees, the

employer must show that: (1) the

employee must be performing work or

services that are seasonal in nature;

and (2) he had been employed for the

duration of the season. Hence, when

the

"seasonal"

workers

are

continuously and repeatedly hired to

perform the same tasks or activities for

several seasons or even after the

cessation of the season, this length of

time may likewise serve as badge of

regular employment.

When dealing with a probationary

employee, the employer is made to

comply with two (2) requirements: first,

the employer must communicate the

regularization standards to the

probationary employee; and second,

the employer must make such

communication at the time of the

probationary employee's engagement.

If the employer fails to comply with

either, the employee is deemed as a

regular and not a probationary

employee.

Infractions committed by an employee

should merit only the corresponding

penalty

demanded

by

the

circumstance. The penalty must be

commensurate

with

the

act,

conduct or omission imputed to the

employee and must be imposed in

Page 6 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

Universal Robina

Sugar

Milling

Corp. v. Acibo

G.R. No. 186439 |

Jan. 15, 2014

Enchanted

Kingdom, Inc. v.

Verzo

G.R. No. 209559 |

Dec. 9, 2015

Negros Slashers

v. Alvin Teng

G.R. No. 187122 |

Feb. 22, 2012

Abasolo v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 118475,

Nov. 29, 2000; citing

Bacolod-Murcia

Milling Co., Inc. v.

NLRC, 204 SCRA

155, 158 [1991];

Visayan Stevedore

Transportation

Company v. CIR, 19

SCRA 426 [1967];

IndustrialCommercial

Agricultural Workers'

Organization

(ICAWO) v. CIR, 16

SCRA 562, 565-566

[1966], Manila Hotel

Company v. Court of

Industrial Relations, 9

SCRA

184,

186

[1963]

Abbott Laboratories

v. Alcaraz, G.R. No.

192571, Jul. 23,

2013; citing Section 6

(d), Rule I, Book VI of

the

Implementing

Rules of the Labor

Code

Sagales v. Rustan's

Commercial Corp.,

G.R. No. 166554,

Nov. 27, 2008; citing

CREA v. NLRC, G.R.

No. 102993, Jul. 14,

1995; citing Radio

Communications of

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

connection with the disciplinary

authority of the employer.

Loss of

confidence;

managerial vs

rank-and-file

employees

Resignation;

requisites

Dismissal for

valid cause but

no procedural

due process

liable for

nominal

damages

With

respect

to

rank-and-file

personnel, loss of trust and confidence

as ground for valid dismissal requires

proof of involvement in the alleged

events in question, and that mere

uncorroborated

assertions

and

accusations by the employer will not

be sufficient. But as regards a

managerial employee, the mere

existence of a basis for believing that

such employee has breached the trust

of his employer would suffice for his

dismissal. Hence, in the case of

managerial employees, proof beyond

reasonable doubt is not required, it

being sufficient that there is some

basis for such loss of confidence, such

as when the employer has reasonable

ground to believe that the employee

concerned is responsible for the

purported misconduct, and the nature

of his participation therein renders him

unworthy of the trust and confidence

demanded by his position.

A resignation must be unconditional

and with the intent to operate as such.

Moreover, the intention to relinquish

an office must concur with the overt act

of relinquishment. The act of the

employee before and after the alleged

resignation must be considered to

determine whether in fact, he or she

intended

to

relinquish

such

employment.

If

the

employer

introduces

evidence

purportedly

executed by an employee as proof of

voluntary

resignation

and

the

employee specifically denies the

authenticity and due execution of said

document, the employer is burdened

to prove the due execution and

genuineness of such document.

Where the dismissal is for a just cause,

as in the instant case, the lack of

statutory due process should not

nullify the dismissal, or render it illegal

or ineffectual. However, the employer

should indemnify the employee for the

violation of his statutory rights, as ruled

in Reta v. National Labor Relations

Commission. The indemnity to be

imposed should be stiffer to

discourage the abhorrent practice of

"dismiss now, pay later," which we

Page 7 of 16

abon3298

Padrillo

Bandojo

v.

G.R. No. 224854 |

March 27, 2019

Fortuny

Garments/Johnny

Co v. Castro

G.R. No. 150668 |

Dec. 15, 2005

Spouses

v. Oreiro

Maynes

G.R. No. 206109 |

Nov. 25, 2020

the Phils. v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 102958,

Jun. 25, 1993

Etcuban,

Jr.

v.

Sulpicio Lines, Inc.,

G.R. No. 148410,

Jan. 17, 2005; citing

Caoile v. NLRC, G.R.

No. 115491, Nov. 24,

1998

AZCOR

Manufacturing, Inc. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

117963, Feb. 11,

1999

Agabon v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 158693,

Nov. 17, 2004

U.P LAW BOC

Abandonment;

requisites

Constructive

dismissal

Preventive

suspension;

when proper

abon3298

sought to deter in the Serrano ruling.

The sanction should be in the nature of

indemnification or penalty and should

depend on the facts of each case,

taking into special consideration the

gravity of the due process violation of

the employer. Under the Civil Code,

nominal damages is adjudicated in

order that a right of the plaintiff, which

has been violated or invaded by the

defendant, may be vindicated or

recognized, and not for the purpose of

indemnifying the plaintiff for any loss

suffered by him.

To prove abandonment, two elements

must concur:

1. Failure to report for work or

absence without valid or justifiable

reason; and

2. A clear intention to sever the

employer-employee relationship

LABOR LAW

Stanley

Furniture

Gallano

Fine

v.

G.R. No. 190486 |

Nov. 26, 2014

Constructive dismissal exists when

there is cessation of work because

continued employment is rendered

impossible, unreasonable or unlikely,

as an offer involving a demotion in rank

and a diminution in pay.

Petchan v. The

Southern

Cross

Hotel Manila, Inc.

Preventive suspension is justified

where the employee's continued

employment poses a serious and

imminent threat to the life or property

of the employer or of the employee's

co-workers. Without this kind of threat,

preventive suspension is not proper.

Maula v. Ximex

Delivery Express,

Inc.

Page 8 of 16

abon3298

G.R. No. 242117

(Notice) | June 3,

2019

G.R. No. 207838 |

Jan. 25, 2017

Josan, JPS, Santiago

Cargo Movers v.

Aduna, G.R. No.

190794, February 22,

2012; citing Icawat v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

133573, June 20,

2000; citing Artemio

Labor vs. NLRC, 248

SCRA 183 [1995],

Cindy and Lynsy

Garment vs. NLRC,

284 SCRA 38 [1998],

and Hagonoy Rural

Bank, Inc. vs. NLRC,

285

SCRA

297

[1998].

Central Azucarera de

Bais, Inc. v. Siason,

G.R. No. 215555,

July 29, 2015; citing

Morales v. Harbour

Centre Port Terminal,

Inc.,

G.R.

No.

174208, Jan. 25,

2012; citing Globe

Telecom,

Inc.

v.

Florendo-Flores, 438

Phil. 756, 766 (2002);

citing

Philippine

Japan Active Carbon

Corporation v. NLRC,

et al., 253 Phil. 149,

152, (1989).

Artificio v. National

Labor

Relations

Commission,

G.R.

No. 172988, July 26,

2010;

citing

Maricalum

Mining

Corp. v. Decorion,

G.R. No. 158637,

April 12, 2006 and

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

Valiao v. CA, G.R.

No. 146621, Jul. 30,

2004; citing Secs. 8

and 9, Rule XXIII,

Implementing Book V

of the Labor Code

Due process in

labor cases

Separation pay

in lieu of

reinstatment;

when proper

The holding of a formal hearing or trial

is discretionary with the Labor Arbiter

and is something that the parties

cannot demand as a matter of right.

The requirements of due process are

satisfied when the parties are given the

opportunity to submit position papers

wherein they are supposed to attach

all the documents that would prove

their claim in case it be decided that no

hearing should be conducted or was

necessary.

Oriental

Shipmanagement

Co., Inc. v. Bastol

As stated, "an illegally dismissed

employee is entitled to reinstatement

as a matter of right." But when an

atmosphere

of

antipathy

and

antagonism has already strained the

relations between the employer and

employee, separation pay is to be

awarded as reinstatement can no

longer be equitably effected.

Litex Glass and

Aluminum Supply

v. Sanchez

G.R. No. 186289 |

June 29, 2010

G.R. No. 198465 |

April 22, 2015

Note:

The

IRR

provisions

on

preventive

suspension

was

deleted after the

issuance of D.O. No.

40-03,

but

jurisprudence

still

cites the provisions

despite their repeal.

Pepsi Cola Products

Philippines, Inc. v.

Santos, G.R. No.

165968, April 14,

2008; citing Shoppes

Manila,

Inc.

v.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission,

G.R.

No. 147125, January

14, 2004; citing Mark

Roche International

v. NLRC, G.R. No.

123825, Aug. 31,

1999

Globe-Mackay Cable

and

Radio

Corporation v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 82511,

March 3, 1992

LABOR RELATIONS

TOPIC

Right to selforganization

includes the

right not to join a

union

Collective

bargaining in the

public sector

DOCTRINE

The right to form or join a labor

organization necessarily includes the

right to refuse or refrain from

exercising the said right. It is selfevident that just as no one should be

denied the exercise of a right granted

by law, so also, no one should be

compelled to exercise such a

conferred right.

Relations between private employers

and their employees are subject to the

minimum requirements of wage laws,

Page 9 of 16

abon3298

CITED IN

Samahan

ng

Manggagawa sa

Hanjin Shipyard v.

Bureau of Labor

Relations

CITING

Reyes v. Trajano.

G.R. No. 84433, June

2, 1992

G.R. No. 211145 |

Oct. 14, 2015

GSIS Family Bank

Employees Union

v. Villanueva

Alliance

of

Government Workers

v. Minister of Labor,

U.P LAW BOC

Mixing of

supervisory and

rank-and-file

employees does

not divest union

of legitimate

labor

organization

status

Confidential

employees also

barred from

joining unions

abon3298

labor, and welfare legislation. Beyond

these

requirements,

private

employers and their employees are at

liberty to establish the terms and

conditions of their employment

relationship. In contrast with the

private sector, the terms and

conditions

of

employment

of

government workers are fixed by the

legislature; thus, the negotiable

matters in the public sector are limited

to

terms

and

conditions

of

employment that are not fixed by law.

The alleged inclusion of supervisory

employees in a labor organization

seeking to represent the bargaining

unit of rank-and-file employees does

not divest it of its status as a legitimate

labor organization.

Although Article 245 of the Labor

Code limits the ineligibility to join, form

and assist any labor organization to

managerial employees, jurisprudence

has extended this prohibition to

confidential employees or those who

by reason of their positions or nature

of work are required to assist or act in

a fiduciary manner to managerial

employees and hence, are likewise

privy to sensitive and highly

confidential records. Confidential

employees are thus excluded from the

rank-and-file bargaining unit. The

rationale for their separate category

and disqualification to join any labor

organization is similar to the inhibition

for managerial employees because if

allowed to be affiliated with a Union,

the latter might not be assured of their

loyalty in view of evident conflict of

interests and the Union can also

become company-denominated with

the

presence

of

managerial

employees in the Union membership.

Having

access to

confidential

information, confidential employees

may also become the source of undue

advantage. Said employees may act

Page 10 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

G.R. No. 210773 |

Jan. 23, 2019

Holy

Child

Catholic School v.

Sto. Tomas

G.R. No. 179146 |

July 23, 2013

Tunay

na

Pagkakaisa

ng

Manggagawa sa

Asia Brewery v.

Asia Brewery, Inc.

G.R. No. 162025,

Aug. 3, 2010

G.R. No. L-60403,

Aug. 3, 1983

Samahang

Manggagawa

sa

Charter

ChemicalSuper v. Charter

Chemical

and

Coating Corp., G.R.

No. 169717, March

16,

2011;

citing

Republic

v.

Kawashima Textile

Mfg.,

Philippines,

Inc.,

G.R.

No.

160352, July 23,

2008

Metrolab Industries,

Inc.

v.

RoldanConfesor, G.R. No.

108855, February 28,

1996; citing Philips

Industrial

Development, Inc. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

88957, June 25, 1992

U.P LAW BOC

Beneficiaries of

CBA

abon3298

as a spy or spies of either party to a

collective bargaining agreement.

The benefits of a collective bargaining

agreement extend to the laborers and

employees in the collective bargaining

unit, including those who do not

belong to the chosen bargaining labor

organization.

LABOR LAW

Mactan Workers

Union v. Aboitiz

G.R. No. L-30241 |

June 30, 1972

Community or

Mutuality of

Interests Test in

determining

appropriate

bargaining unit

The basic test for determining the

appropriate bargaining unit is the

application of a standard whereby a

unit is deemed appropriate if it affects

a grouping of employees who have

substantial, mutual interests in wages,

hours, working conditions, and other

subjects of collective bargaining.

Ang

Lee

v.

Samahang

Manggagawa ng

Super Lamination

Factors in

determining

bargaining unit

The

fundamental

factors

in

determining the appropriate collective

bargaining unit are: (1) the will of the

employees (Globe Doctrine); 6 (2)

affinity and unity of the employees'

interest, such as substantial similarity

of work and duties, or similarity of

compensation and working conditions

(Substantial Mutual Interests Rule);

(3) prior collective bargaining history;

and (4) similarity of employment

status.

A local union which has affiliated itself

with a federation is free to sever such

affiliation

anytime

and

such

disaffiliation cannot be considered

disloyalty. In the absence of specific

provisions

in

the

federation's

constitution prohibiting disaffiliation or

the declaration of autonomy of a local

union, a local may dissociate with its

parent union.

Sta.

Lucia

Commercial Corp.

v. Secretary of

Labor

and

Employment

Right to

disaffiliate

Page 11 of 16

abon3298

G.R. No. 193816 |

Nov. 21, 2016

Leyte

Land

Transportation

v.

Leyte Farmers' and

Laborers' Union, 80

Phil. 842 (1948);

Land Settlement and

Development

Corporation

v.

Caledonia

Pile

Workers' Union, 90

Phil. 817 (1952);

Price

Stabilization

Corporation v. Prisco

Workers' Union, 104

Phil. 1066 (1958) and

International

Oil

Factory

Workers

Union v. Martinez,

110 Phil. 595 (1960).

University of the

Phils.

v.

FerrerCalleja, G.R. No.

96189, July 14, 1992;

citing

Democratic

Labor Association v.

Cebu

Stevedoring

Company, Inc., G.R.

No. L-10321, Feb. 28,

1958

San Miguel Corp. v.

Laguesma, G.R. No.

100485, Sept. 21,

1994

G.R. No. 162355 |

Aug. 14, 2009

National Union of

Bank Employees

v.

Philnabank

Employees

Association

G.R. No. 174287 |

Aug. 12, 2013

MSMG-UWP v. Hon.

Ramos, G.R. No.

113907, Feb. 28,

2000; citing Ferrer vs.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission,

224

SCRA 410; People's

Industrial

and

Commercial

Employees

and

Workers

Organization (FFW)

vs.

People's

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

Disaffiliation of

affiliated union

without

independent

registration;

effect

A local union which is not

independently registered cannot,

upon disaffiliation from the federation,

exercise the rights and privileges

granted by law to legitimate labor

organizations; thus, it cannot file a

petition for certification election.

Fraud and

misrepresentation as ground

for cancellation

of union

registration

For fraud and misrepresentation to

constitute grounds for cancellation of

union registration under the Labor

Code, the nature of the fraud and

misrepresentation must be grave and

compelling enough to vitiate the

consent of a majority of union

members.

Attorney's fees

only chargeable

to union funds;

exception

A deadlock

presupposes

reasonable

effort at good

faith bargaining

Labor contracts

construed in

favor of labor

The general rule is that attorney's

fees, negotiation fees, and other

similar charges may only be collected

from union funds, not from the

amounts that pertain to individual

union members. As an exception to

the general rule, special assessments

or other extraordinary fees may be

levied upon or checked off from any

amount due an employee for as long

as there is proper authorization by the

employee.

A 'deadlock' is . . . the counteraction

of things producing entire stoppage; .

. . There is a deadlock when there is a

complete blocking or stoppage

resulting from the action of equal and

opposed forces . . . . The word is

synonymous with the word impasse,

which . . . 'presupposes reasonable

effort at good faith bargaining which,

despite noble intentions, does not

conclude in agreement between the

parties.'

Article 1702 of the New Civil Code

provides that, in case of doubt, all

labor legislation and all labor

contracts shall be construed in favor

of the safety and decent living of the

laborer. Thus, this Court has ruled

that any doubt or ambiguity in the

contract between management and

the union members should be

resolved in favor of the latter.

Page 12 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

Abaria v. National

Labor

Relations

Commission

G.R. Nos. 154113,

187778, 187861 &

196156 | Dec. 7,

2011

De

Ocampo

Memorial Schools,

Inc.

v.

Bigkis

Mangga-gawa sa

De

Ocampo

Memorial School,

Inc.

G.R. No. 192648 |

March 15, 2017

Mariño,

Jr.

v.

Gamilla

Industrial

and

Commercial Corp.,

112 SCRA 440

Villar v. Inciong, Nos.

L-50283-84, April 20,

1983

Mariwasa

Siam

Ceramics, Inc. v.

Secretary

of

the

Department of Labor

and Employment

G.R. No. 183317 |

Dec. 21, 2009

BPI

Employees

Union-ALU v. NLRC

G.R. No. 149763 |

July 7, 2009

G.R. Nos. 69746-47,

76842-44, 76916-17 |

March 31, 1989

Tabangao

Shell

Refinery

Employees

Association

v.

Pilipinas

Shell

Petroleum Corp.

Capitol

Medical

Center Alliance of

Concerned

Employees-UFSW v.

Laguesma, G.R. No.

118915, February 4,

1997; citing Divine

Word University of

Tacloban

v.

Secretary of Labor

and

Employment,

G.R. No. 91915,

September 11, 1992

Holy Cross of Davao

College, Inc. v. Holy

Cross

of

Davao

Faculty

UnionKAMAPI, G.R. No.

156098, June 27,

2005, 461 SCRA 319,

Babcock-Hitachi

(Phils.),

Inc.

v.

Babcock

Hitachi

(Phils.), Inc., Makati

G.R. No. 170007 |

April 7, 2014

Bank

of

the

Philippine Islands

v. Bank of the

Philippine Islands

Employees UnionMetro Manila

G.R. No. 175678 |

Aug. 22, 2012

U.P LAW BOC

Preconditions

for collective

bargaining

ULP; how

committed

Dismissal based

on union

security clause

abon3298

The

mechanics

of

collective

bargaining are set in motion only

when the following jurisdictional

preconditions are present, namely, (1)

possession of the status of majority

representation by the employees'

representative in accordance with any

of the means of selection and/or

designation provided for by the Labor

Code;

(2)

proof

of

majority

representation; and (3) a demand to

bargain.

In the past, we have ruled that "unfair

labor practice refers to 'acts that

violate the workers' right to organize.'

The prohibited acts are related to the

workers' right to self-organization and

to the observance of a CBA." We have

likewise declared that "there should

be no dispute that all the prohibited

acts constituting unfair labor practice

in essence relate to the workers' right

to self-organization." Thus, an

employer may only be held liable for

unfair labor practice if it can be shown

that his acts affect in whatever

manner the right of his employees to

self-organize.

To validly terminate the employment

of an employee through the

enforcement of the union security

clause, the following requisites must

concur: (1) the union security clause

is applicable; (2) the union is

requesting for the enforcement of the

union security provision in the CBA;

Page 13 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

Associated Labor

Unions v. FerrerCalleja

Employees

Union,

G.R. No. 156260,

March 10, 2005, 453

SCRA 156, 161;

Mindanao

Steel

Corporation

v.

Minsteel

Free

Workers

Organization

Cagayan de Oro,

G.R. No. 130693,

March 4, 2004, 424

SCRA 614, 618 and

Plastic Town Center

Corporation

v.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission,

G.R.

No. 81176, April 19,

1989, 172 SCRA 580,

587.

Kiok Loy v. NLRC,

G.R. No. L-54334,

Jan. 22, 1986

G.R. No. 77282 |

May 5, 1989

Culili v. Eastern

Telecommunications Philippines,

Inc.

G.R. No. 165381 |

Feb. 9, 2011

Slord

Development

Corp. v. Noya

G.R. No. 232687 |

Feb. 4, 2019

Great Pacific Life

Employees Union v.

Great Pacific Life

Assurance

Corp.,

G.R. No. 126717,

February 11, 1999

General

Milling

Corporation v. Casio,

G.R. No. 149552,

March 10, 2010;

citing

Alabang

Country Club, Inc. v.

National

Labor

Relations

U.P LAW BOC

Procedural

requirements for

strike are

mandatory

Good faith as

defense against

illegal strike

abon3298

and (3) there is sufficient evidence to

support the decision of the union to

expel the employee from the union.

It is settled that [the procedural

requirements for a valid strike] are

mandatory in nature and failure to

comply therewith renders the strike

illegal.

Generally, a strike based on a "nonstrikeable" ground is an illegal strike:

corollarily, a strike grounded on ULP

is illegal if no such acts actually exist.

As an exception, even if no ULP acts

are committed by the employer, if the

employees believe in good faith that

ULP acts exist so as to constitute a

valid ground to strike, then the strike

held pursuant to such belief may be

legal.

LABOR LAW

Pilipino Telephone

Corp. v. Pilipino

Telephone

Employees

Association

G.R. Nos. 160058

&160094 | June 22,

2007

National Union of

Workers in Hotels,

Restaurants and

Allied Industries v.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission

G.R. No. 125561 |

March 6, 1998

Commission,

G.R.

No.

170287,

February 14, 2008

CCBPI

Postmix

Workers Union v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

114521, November

27, 1998

Panay Electric Co.,

Inc.

vs.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission, et al, G

R.

No.

102672,

October 4, 1995, 248

SCRA 688; Master

Iron Labor Union

(MILU), et al. vs.

National

Labor

Relations

Commission, et al.,

G.R

No.

92009,

February 17, 1993,

219

SCRA

47;

People's

Industrial

and

Commercial

Employee's

and

Workers

Organization (FFW),

et al. vs. People's

Industrial

and

Commercial

Corporation, et al., L37687, March 15,

1982, 112 SCRA 440

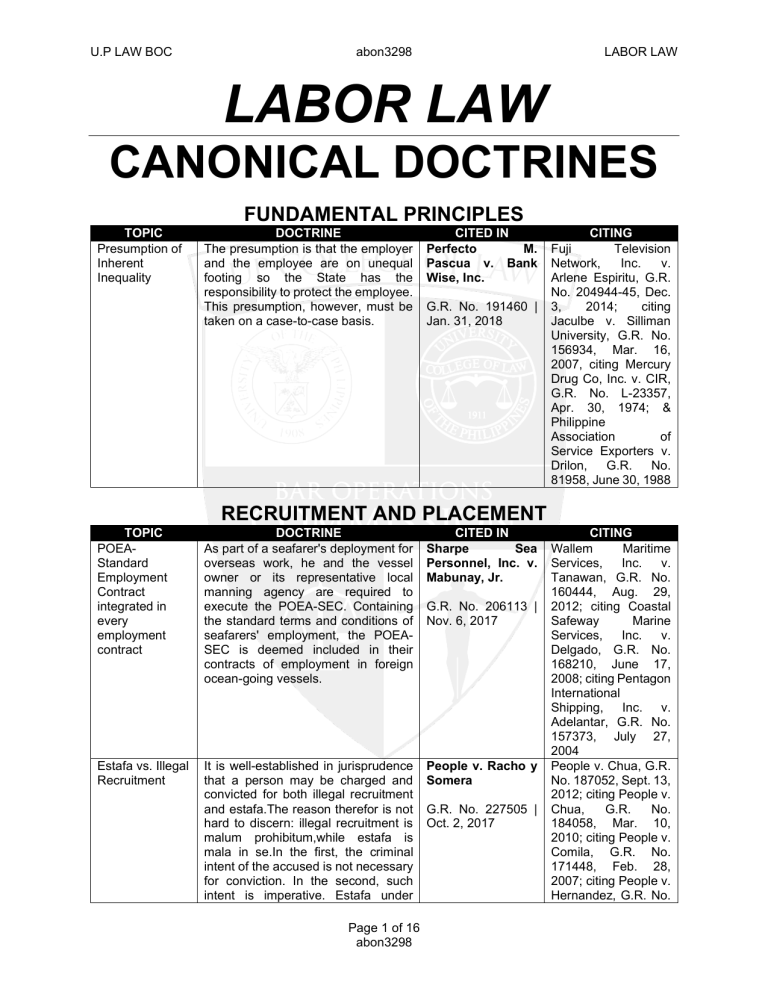

MANAGEMENT PREROGATIVE

TOPIC

Rights of

Management

DOCTRINE

While our laws endeavor to give life to

the constitutional policy on social

justice and the protection of labor, it

does not mean that every labor

dispute will be decided in favor of the

workers. The law also recognizes that

management has rights which are

also entitled to respect and

enforcement in the interest of fair play.

Page 14 of 16

abon3298

CITED IN

St. Luke’s Medical

Center Employees

Association - AFW

v. National Labor

Relations

Commission

G.R. No. 162053 |

March 7, 2007

CITING

Duncan Association

of

DetailmanPTGWO v. Glaxo

Wellcome

Philippines, Inc., G.R.

No.

162994,

September 17, 2004;

citing Sta. Catalina

College v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 144483,

Nov. 19, 2003; citing

Sosito v. Aguinaldo

Development Corp.,

G.R. No. L-48926,

Dec. 14, 1987

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

Management

Prerogative

The right of an employer to regulate

all aspects of employment, aptly

called "management prerogative,"

gives employers the freedom to

regulate, according to their discretion

and best judgment, all aspects of

employment,

including

work

assignment,

working

methods,

processes to be followed, working

regulations, transfer of employees,

work supervision, lay-off of workers

and the discipline, dismissal and

recall of workers. In this light, courts

often decline to interfere in legitimate

business decisions of employers. In

fact,

labor

laws

discourage

interference in employers' judgment

concerning the conduct of their

business.

It is well recognized that company

policies and regulations are, unless

shown to be grossly oppressive or

contrary to law, generally binding and

valid on the parties and must be

complied with until finally revised or

amended unilaterally or preferably

through negotiation or by competent

authority.

St. Luke's Medical

Center, Inc. v.

Sanchez

Although jurisprudence recognizes

the validity of the exercise by an

employer

of

its

management

prerogative and will ordinarily not

interfere with such, this prerogative is

not absolute and is subject to

limitations imposed by law, collective

bargaining agreement, and general

principles of fair play and justice.

Hongkong Bank

Independent

Labor Union v.

Hongkong

and

Shanghai Banking

Corp. Limited

We have long recognized the

prerogative of management to

transfer an employee from one office

to another within the same business

establishment, as the exigency of the

business may require, provided that

the transfer does not result in a

demotion in rank or a diminution in

salary, benefits and other privileges of

Duldulao v. Court

of Appeals

Validity of

Company Policy

Management

Prerogative

subject to CBA

Transfer is valid

management

prerogative

Page 15 of 16

abon3298

LABOR LAW

G.R. No. 212054 |

March 11, 2015

China

Banking

Corp. v. Borromeo

G.R. No. 156515|

Oct.19, 2004

G.R. No. 218390 |

Feb. 28, 2018

G.R. No. 164893,

March 1, 2007

Philippine Industrial

Security

Agency

Corp. v. Aguinaldo,

G.R. No. 149974,

June 15, 2005; citing

Mendoza vs. Rural

Bank of Lucban, G.R.

No. 155421, July 7,

2004; citing Metrolab

Industries, Inc. vs.

Roldan-Confesor,

G.R. No. 108855,

Feb. 28, 1996; &

Bontia vs. NLRC, 325

Phil. 443 (1996)

Alcantara, Jr. v. CA,

G.R. No. 143397,

Aug., 2, 2002; citing

San Miguel Corp. v.

Ubaldo, G.R. No.

92859, Feb. 1, 1993;

citing

GTE

Directories

Corporation

vs.

Sanchez, G.R. No.

76219, May 27, 1991

Morales v. Harbour

Centre Port Terminal,

G.R. No. 174208,

Jan. 25, 2012; citing

Norkis Trading v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

168159, Aug, 19,

2005;

citing

Philippine

Airlines,

Inc. v. NLRC, G.R.

No. 85985, 13 August

1993; citing UST v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

89920, Oct. 18, 1990;

citing

Abbott

Laboratories [Phil.]

Inc. v. NLRC, 154

SCRA 713 [1987];

Sentinel

Security

Agency, G.R. No.

122468, September

3, 1998; citing Asis v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

82478, Sept. 7, 1989,

Chu v. NLRC, G.R.

No. 106107 Jun. 2,

1994,

Pocketbell

U.P LAW BOC

abon3298

LABOR LAW

the employee; or is not unreasonable,

inconvenient or prejudicial to the

latter; or is not used as a subterfuge

by the employer to rid himself of an

undesirable worker.

Enforceability of

Bonus

Bona fide

occupational

qualification

For a bonus to be enforceable, it must

have been promised by the employer

and expressly agreed upon by the

parties, or it must have had a fixed

amount and had been a long and

regular practice on the part of the

employer. To be considered a "regular

practice," the giving of the bonus

should have been done over a long

period of time, and must be shown to

have been consistent and deliberate.

American

Wire

and Cable Daily

Rated Employees

Union v. American

Wire and Cable

Co.

To justify a bona fide occupational

qualification, the employer must prove

two factors: (1) that the employment

qualification is reasonably related to

the essential operation of the job

involved; and, (2) that there is a

factual basis for believing that all or

substantially all persons meeting the

qualification would be unable to

properly perform the duties of the job.

Capin-Capiz

v.

Brent Hospital and

Colleges, Inc.

G.R. No. 155059 |

April 29, 2005

G.R. No. 187417 |

Feb. 24, 2016

Phils., Inc. v. NLRC,

G.R. No. 10683, Jan.

20,

1995,

and

Philippine Telegraph

and Telephone Co. v.

Laplana, G.R. No.

76645, Jul. 23, 1991

Philippine Appliance

Corp. v. CA, G.R. No.

149434, June 3,

2004; citing Globe

Mackay Cable v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

74156, June 29,

1988; citing Oceanic

Pharmacal

Employees Union v.

Inciong, G.R. No. L50568, Nov. 7, 1979

Star Paper Corp. v.

Simbol, G.R. No.

164774, April 12,

2006;

citing

Philippine Telegraph

& Telephone Co. v.

NLRC, G.R. No.

118978, May 23,

1997

JURISDICTION AND REMEDIES

TOPIC

"Reasonable

Causal

Connection" and

the jurisdiction

of labor tribunals

DOCTRINE

The money claims within the original

and exclusive jurisdiction of labor

arbiters are those which have some

reasonable causal connection with

the employer-employee relationship.

Page 16 of 16

abon3298

CITED IN

Paredes v. Feed

the

Children

Phils., Inc.

G.R. No. 184397 |

Sept. 9, 2015

CITING

Portillo v. Rudolf Lietz,

Inc., G.R. No. 196539,

October 10, 2012;

citing San Miguel v.

NLRC,

G.R.

No.

80774, May 31, 1988