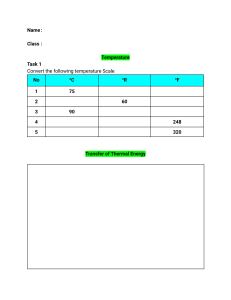

Journal of ELECTRONIC MATERIALS, Vol. 42, No. 7, 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s11664-013-2488-0 Ó 2013 TMS Two-Dimensional Thermal Resistance Analysis of a Waste Heat Recovery System with Thermoelectric Generators GIA-YEH HUANG1 and DA-JENG YAO1,2,3 1.—Department of Power Mechanical Engineering, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu 30013, Taiwan, ROC. 2.—Institute of NanoEngineering and MicroSystems, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu 30013, Taiwan, ROC. 3.—e-mail: djyao@mx.nthu.edu.tw In this study, it is shown that two-dimensional (2D) thermal resistance analysis is a rapid and simple method to predict the power generated from a waste heat recovery system with thermoelectric generators (TEGs). Performance prediction is an important part of system design, generally being simulated by numerical methods with high accuracy but long computational duration. Use of the presented analysis saves much time relative to such numerical methods. The simple 2D model of the waste heat recovery system comprises three parts: a recovery chamber, the TEGs, and a cooling system. A fin-structured duct serves as a heat recovery chamber, to which were attached the hot sides of two TEGs; the cold sides were attached to a cooling system. The TEG module and duct had the same width. In the 2D analysis, unknown temperatures are located at the centroid of each cell into which the system is divided. The relations among the unknown temperatures of the cells are based on the principle of energy conservation and the definition of thermal resistance. The temperatures of the waste hot gas at the inlet and of the ambient fluid are known. With these boundary conditions, the unknown temperatures in the system become solvable, and the power generated by the TEGs can be predicted. Meanwhile, a three-dimensional (3D) model of the system was simulated in FloTHERM 9.2. The 3D numerical solution matched the solution of the 2D analysis within 10%. Key words: Thermal resistance, waste heat recovery system, thermoelectric generator, modeling INTRODUCTION Thermoelectric generators (TEGs) have been studied for more than a century. In many applications, the TEG converts heat into electricity.1–5 In the reported work on models of waste heat recovery systems, harvesting of energy from exhaust heat is emphasized. Computational methods and models of thermal resistance assist in analysis and improve performance.6–9 In the present work, a model of a waste heat recovery system was developed using two-dimensional thermal resistance analysis. This method helps to solve the temperature gradient of the TEG (Received July 19, 2012; accepted January 10, 2013; published online February 20, 2013) 1982 modules. The solutions enable performance estimates of waste heat recovery systems. The same systems were modeled using FloTHERM 9.2 software. The solutions of the thermal resistance model are compared with the results of simulations. TWO-DIMENSIONAL THERMAL RESISTANCE The concept of 2D thermal resistance is based on one-dimensional (1D) thermal resistance. The thermal resistance circuit is an electrical analogy with heat transfer. The heat rate (Q) is analogous to the current flow in an electric circuit. The analog of the temperature difference (DT) is the voltage difference. In 1D thermal resistance analysis, the thermal resistance is defined as Two-Dimensional Thermal Resistance Analysis of a Waste Heat Recovery System with Thermoelectric Generators R¼ DT : Q 1983 (1) For heat transfer by conduction, the thermal resistance in one dimension is defined as Rcond ¼ L ; kA (2) where L denotes the length of material, A the contact area, and k the thermal conductivity. For convective heat transfer, the thermal resistance is defined as Rconv ¼ 1 ; hA (3) where h denotes the convective heat transfer coefficient. Usually, thermoelectric effects are considered for thermoelectric devices. The thermal energy flowing into a thermoelectric device is not equal to the thermal energy flowing out of the other side, as part of the thermal energy is converted into electric power. Based on theoretical calculations for the operating conditions and TEG module properties considered in this study, the best efficiency of the TEGs in the system with and without consideration of thermoelectric effects is 5.21% and 5.64%. Due to the small size of this difference, the thermoelectric effects are neglected and the heat energy is assumed to be conserved for the TEGs. Therefore, the principle of energy conservation is also applied in the 2D thermal resistance analysis. In the 2D analysis, the computational domain is divided into several cells; the temperatures nodes are located at the centroid of each cell, as shown in Fig. 1. For each cell, the heat flowing in equals the heat flowing out. Moreover, the relation between two nodes is developed based on the definition of thermal resistance as represented in Eq. 4. Ti Te Ti Tw Ti Tn Ti Ts þ þ þ ¼ 0: Re Rw Rn Rs (4) The method for solving the estimated performance of a simple waste heat recovery system is as follows. Figure 2 shows that the system comprises three parts: a heat recovery chamber, the TEGs, and a cooling system. To the fin-structured duct that serves as a heat recovery chamber is attached the hot sides of two TEGs. The properties of the commercial TEG module (TMH400302055; Wise Life Technology, Taiwan) considered in this work are listed in Table I. The cold sides of the TEGs are attached to a cooling system; in this case, heat sinks serve as the cooling system. The TEG module and the duct have the same width. For the 2D analysis to solve the problem, nodes with unknown temperatures are located at the centroid of each cell into which the waste heat Fig. 1. Relation developed among one node (Ti) and four other nodes (Te, Tw, Tn, Ts) with a definition for thermal resistance. recovery system has been divided. The relation between one node and another is developed based on the definition of thermal resistance. In Fig. 3, the black nodes are the boundary conditions. The relations among wall nodes (square) are expressed as Eq. 4, but the relations among the end nodes (triangle) must be corrected for their positions. When the end nodes lack eastern nodes, Eq. 4 is rewritten as Eq. 5. When the end nodes lack western nodes, Eq. 4 is rewritten as Eq. 6. Ti Tw Ti Tn Ti Ts þ þ ¼ 0; Rw Rn Rs (5) Ti Te Ti Tn Ti Ts þ þ ¼ 0: Re Rn Rs (6) For the interior chamber nodes (diamond), the relation is expressed as Eq. 7. mcp Ti ¼ mcp Ti1 q_ v ; (7) where q_ v is the heat flowing in the vertical direction. The relations involve the matrix Eq. 8. Solving this matrix, the unknown temperatures in the system are revealed. The estimated performance of the waste heat recovery system is then predictable by Eq. 9. 2 32 3 2 3 a11 a125 C1 T1 6 .. .. 76 .. 7 6 .. 7 .. (8) 4 . . 54 . 5 ¼ 4 . 5 . T25 C25 a251 a2525 1984 Huang and Yao Fig. 2. (a) Prototypical simple waste heat recovery system: (1) first TEG, (2) first heat sink, (3) second TEG, (4) second heat sink, (5) waste heat recovery chamber; (b) front view of the system; (c) schematic diagram of the system. Table I. Properties of a TE couple Seebeck coefficient (V K1) Resistivity (X m) Thermal conductivity (W m1 K1) Z (K1) Thermal resistivity (K W1) Contact area (m2) Thickness (m) P ¼ I 2 RL ¼ aDT R n-Type p-Type Copper Ceramic Solder 2.12 9 104 1.04 9 105 1.456 2.97 9 103 109.89 4 9 106 6.4 9 104 2.15 9 104 1.04 9 105 1.373 3.23 9 103 116.79 4 9 106 6.4 9 104 N/A 3.2 9 108 385 N/A 0.1443 9 9 106 5 9 104 N/A 1 9 1012 22 N/A 3.207 9 9 106 6.35 9 104 N/A 12.1 9 108 50 N/A 0.25 4 9 106 5 9 105 2 RL ; (9) where a is the Seebeck coefficient, DT is the temperature difference, R is the total electric resistance in the circuit, and RL is the external load resistance. ESTIMATION OF THE CONVECTIVE HEAT TRANSFER COEFFICIENT In the waste heat recovery system, convective heat transfer plays an important role because heat is transfered from the waste hot gas to the wall of the recovery chamber by convection. Outside the recovery chamber, the cooling mechanism is also strongly related to convective heat transfer. With these coefficients, the thermal resistances can be defined and applied in the 2D analysis. In this study, the convective heat transfer coefficient applied in the 2D analysis is estimated as follows. According to Benjan,10 the convective heat transfer coefficient is estimated for external flow. When a fluid flows over heat sinks, the fin efficiency is considered in the calculation of the thermal resistance. For internal duct flow, there are two conditions; the first is that fluid flows in a duct as shown in Fig. 4a, for which the convective heat transfer coefficient is estimated from Kurtbaş.11 The second is that the fluid flows in a fin-structured duct as shown in Fig. 4b. In this case, the convection heat transfer coefficient is estimated from the method of Knight et al.12 RESULTS The performance of the simple waste heat recovery system of Fig. 2 was estimated using the Two-Dimensional Thermal Resistance Analysis of a Waste Heat Recovery System with Thermoelectric Generators described 2D thermal resistance analysis. Also, the same system was modeled using commercial software (FloTHERM 9.2). As we neglect thermoelectric effects, FloTHERM is sufficient to model the system, without thermoelectric effects. The dimensions and material properties used in the simulation are listed in Table II. Two factors are considered in this model: the velocities of the internal hot gas (Vi) and 1985 of the external cold air (Ve). The operational and boundary conditions are listed in Table III. Figures 5 and 6 show the temperatures of the hot side (Th) and the cold side (Tc) of the TEGs. On average, the results from the 2D analysis and simulations differ by about 10%. In this study, the performance of waste heat recovery systems of three other types, as shown in Fig. 4a–c, was also estimated by using the 2D thermal resistance analysis and modeling of the same systems using FloTHERM 9.2. The simple waste heat recovery system is shown in Fig. 4d. For the other three systems, the results from the 2D analysis and the simulations differed by 10% on average. DISCUSSION Influence of Flow Velocity Fig. 3. The thermal resistance model in the simple waste heat recovery system. To develop the relationship between the performance and the flow velocity, we considered 12 conditions for the flow velocity. Applying the 2D analysis to develop this relation requires only a few minutes. The power generated by the system increases with increasing velocity. The external flow velocity of the cold gas affects the power generated more than the internal velocity. When the external flow velocity of cold gas increases from 6 m/s to 12 m/s, the power generated increases by 1.5 times, whereas when the internal flow velocity of hot gas increases from 12 m/s to 24 m/s, the power generated increases by 1.3 times, as shown in Fig. 7. Fig. 4. Another prototypical waste heat recovery system: (a) type 1: a nonstructured duct works as a chamber for heat recovery, (b) type 2: a finstructured duct works as a chamber for heat recovery, (3) type 3: a nonstructured duct works as a chamber for heat recovery and TEGs are attached to heat sinks, (d) type 4: a fin-structured duct works as a heat recovery chamber and TEGs are attached to heat sinks. 1986 Huang and Yao Table II. Dimensions and material properties used in simulations (FloTHERM 9.2) (a) Waste heat recovery chamber Dimensions (mm3) Number of internal fins Fin thickness (mm) Fin base thickness (mm) Material (b) Heat sink Dimensions (mm3) Number of internal fins Fin thickness (mm) Fin base thickness (mm) Material (c) TEG module Dimensions (mm3) Equivalent conductivity (W m1 K1) 270 (L) 9 54 (W) 9 56 (H) 6 2.5 5 Aluminum 52 (L) 9 54 (W) 9 40 (H) 12 2 6 Aluminum 52 (L) 9 54 (W) 9 2.8 (H) 3.2563 Table III. Operational and boundary conditions Factor Condition 1 Internal hot gas velocity (m s ) External cold air velocity (m s1) Ambient temperature (°C) Inlet temperature of hot gas (°C) 1 12 3 6 24 8 10 15 27 200 Influence of the Fin Structure The performance of four system designs was estimated quickly using the 2D analysis. Based on the calculation results, both heat sinks and finstructured ducts enhance the heat transfer. Relative to nonstructured ducts (type 1), the power generated with fin-structured ducts (type 2) is 1.1 to 2.3 times. When heat sinks are attached to the cold sides of the TEGs (type 3), the power generated increases about 25 times. With heat sinks and fin-structured ducts (type 4), the power generated increases over 100 times, as shown in Fig. 7; this system design improves the performance most. Influence of Thermal Resistance Thermal resistance is an important factor affecting the power generated. The 2D analysis reveals the relations among the thermal resistance and other factors, including fin- or nonstructured ducts, with or without attached heat sinks, as well as the internal and external flow velocities. Figure 8 shows that the thermal resistance of fin-structured ducts and heat sinks is smaller than for nonstructured ducts and no heat sink attached. Increasing the flow velocities of the internal hot gas and the external cold gas also might decrease the thermal resistance, but the varied duct designs and heat sink attachment are more effective. Attachment of heat sinks effectively decreases the thermal resistance the most. Fig. 5. Temperature of TEG modules with inlet velocity of 12 m/s: (a) first TEG, (b) second TEG. CONCLUSIONS Two-dimensional thermal resistance analysis is a rapid and simple method to predict the temperature difference of TEGs, so that the performance of waste heat recovery systems can be estimated. The results of the 2D analysis are consistent with simulation Two-Dimensional Thermal Resistance Analysis of a Waste Heat Recovery System with Thermoelectric Generators 1987 Fig. 8. Relation among thermal resistance, velocity conditions, and system designs. results; the average difference between the results from the 2D method and from simulation is about 10%. This method is efficient to estimate the power generated from the system. The numerical method provides a more accurate prediction but requires much time; the 2D analysis saves time. With varied parameters, the relations between various factors and the performance are readily revealed. The method helps to determine quickly the most effective factor affecting the performance. Fig. 6. Temperature of TEG modules with inlet velocity of 24 m/s: (a) first TEG, (b) second TEG. REFERENCES Fig. 7. Relation among power generated, velocity conditions, and system designs. 1. T. Kajikawa and T. Onishi, Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, IEEE (2007), p. 322. 2. N.D. Love, J.P. Szybist, and C.S. Sluder, Appl. Energy 89, 322 (2012). 3. M. Kishi, H. Nemoto, T. Hamao, M. Yamamoto, S. Sudou, M. Mandai, and S. Yamamoto, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, IEEE (1999), p. 301. 4. T. Ota, K. Fujita, S. Tokura, and K. Uematsu, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, IEEE (2006), p. 354. 5. C. Eisenhut and A. Bitschi, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, IEEE (2006), p. 510. 6. Y.Y. Hsiao, W.C. Chang, and S.L. Chen, Energy 35, 1447 (2010). 7. X. Gou, H. Xiao, and S. Yang, Appl. Energy 87, 3131 (2010). 8. N. Espinosa, M. Lazard, L. Aixala, and H. Scherrer, J. Electron. Mater. 39, 1446 (2010). 9. F. Meng, L. Chen, and F. Sun, Energy 36, 3513 (2011). 10. A. Bejan, Convection Heat Transfer, 3rd ed. (New York: Wiley, 2004), pp. 351–357. _ Kurtbaş, Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 33, 140 (2008). 11. I. 12. R.W. Knight, D.J. Hall, J.S. Goodling, and R.C. Jaeger, IEEE Trans. Compon. Hybrids Manuf. Technol. 15, 832 (1992).