Chapter 11

Cash Flows and Capital Budgeting

Learning Objectives

1. Explain why incremental after-tax free cash flows are relevant in evaluating a project,

and be able to calculate them for a project.

2. Discuss the five general rules for incremental after-tax free cash flow calculations, and

explain why cash flows stated in nominal (real) dollars should be discounted using a

nominal (real) discount rate.

3. Describe how distinguishing between variable and fixed costs can be useful in

forecasting operating expenses.

4. Explain the concept of equivalent annual cost, and be able to use it to compare projects

with unequal lives, decide when to replace an existing asset, and calculate the

opportunity cost of using an existing asset.

5. Determine the appropriate time to harvest an asset.

I.

Chapter Outline

Calculating Project Cash Flows

•

In capital budgeting, we estimate the NPV of the cash flows that a project is expected to

produce in the future.

•

A.

All of the cash flow estimates are forward-looking.

Incremental After-Tax Free Cash Flows

•

The cash flows we discount in an NPV analysis are the incremental after-tax free

cash flows , which refers to the fact that these cash flows reflect the amount by

which the firm’s total after-tax free cash flows will change if the project is

adopted. See Equation 11.1:

o FCFProject = FCFFirm with project – FCFFirm without project

•

The term free cash flows (FCF) refers to the fact that the firm is free to distribute

these cash flows to creditors and stockholders because these are the cash flows that

are left over after a firm has made necessary investments in working capital and

long-term assets.

B.

The FCF Calculation

•

Referring to 11.2, which is a more detailed version of 11.1:

FCF = [(Revenue – Op Exp – D&A) x (1 – t)] + D&A – Cap Ex – Add WC

•

We first compute the incremental cash flow from operations (CF Opns), which is

the cash flow that the project is expected to generate after all operating expenses

and taxes have been paid.

•

We then subtract the incremental capital expenditures (Cap Ex) and incremental

additions to working capital (Add WC) required for the project to obtain FCF.

•

The FCF is therefore a measure of the after-tax cash flows from operations over

and above what is necessary to make any required investments.

•

The idea that we can evaluate the cash flows from a project independently of the

cash flows for the firm is known as the stand-alone principle. It is another way of

saying that we can treat the project as if it is a stand-alone firm that has its own

revenue, expenses, and investment requirements.

C. Cash Flows from Operations

•

Note that the incremental cash flow from operations, CF Opns, equals the

incremental net operating profits after tax (NOPAT) plus the incremental

depreciation and amortization (D&A) associated with the project.

•

We exclude interest expenses when calculating NOPAT because the cost of

financing a project is reflected in the discount rate that is used in the NPV

calculation.

•

We use the firm’s marginal tax rate (t) to calculate NOPAT because the profits

from a project are assumed to be incremental to the firm.

•

We add incremental depreciation and amortization (D&A) to NOPAT when

calculating CF Opns because, as in the accounting statement of cash flows, D&A

represents a noncash charge that reduces the firm’s tax obligation.

•

However, since D&A is a noncash charge, we have to add it back to

NOPAT in order to get the cash flow from operations right.

D. Cash Flows Associated with Investments

•

Once we have estimated CF Opns, we simply subtract cash flows associated with

required investment to obtain FCF for a project in a particular period.

•

Investments can be required to purchase long-term tangible assets and intangible

assets, or to fund current assets.

E. FCF versus Accounting Earnings

•

The impact of a project on a firm’s overall value or on its stock price

does not depend on how the project affects the company’s accounting earnings. It

depends only on how the project affects the company’s free cash flows.

•

Accounting earnings can differ from cash flows for a number of

reasons, making accounting earnings an unreliable measure of the costs and

benefits of a project.

•

Accounting earnings also reflect noncash charges, such as depreciation

and amortization, which are intended to account for the costs associated with

deterioration of the assets in a business as those assets are used.

11.2

Estimating Cash Flows in Practice

A.

Five General Rules for Incremental Cash Flow Calculations

•

Rule 1: Include cash flows and only cash flows in your calculations. Do not

include allocated costs or overhead unless they reflect cash flows.

•

Rule 2: Include the impact of the project on cash flows from other product lines. If

the product associated with a project is expected to cannibalize or boost sales of

another product, you must include the expected impact of the new project on the

cash flows from the other product in the analysis.

•

Rule 3: Include all opportunity costs. By opportunity costs, we mean the cost of

giving up another opportunity.

•

Rule 4: Forget sunk costs. Sunk costs are costs that have already been incurred,

but all that matters when you evaluate a project at a particular point in time is how

much you have to invest in the future and what you could expect to receive in

return for that investment; this means that past investments are irrelevant.

•

Rule 5: Include only after-tax cash flows in the cash flow calculations. The

incremental pretax earnings of a project only matter to the extent that they affect

the after-tax cash flows that the firm’s investors receive.

B.

Nominal versus Real Cash Flows

•

Nominal dollars are the dollars that we typically think of. They represent the actual

dollar amounts that we expect a project to generate in the future, without any

adjustments.

•

When prices are going up, a given nominal dollar amount will buy less and less

over time.

o Real dollars represent dollars stated in terms of constant purchasing power.

•

We can write the cost of capital , k, as

o 1 + k = (1 + ∆Pe) x (1 + r)

o r is the real cost of capital

o (∆Pe) is the expected rate of inflation

o (r) is the real rate of return

•

It is important to make sure that all cash flows are stated in either nominal dollars

or real dollars.

C.

Tax Rates and Depreciation

•

A progressive tax system, which we have in the United States, is one in which the

marginal tax rate at low levels of income is lower than the marginal tax rate at high

levels of income.

•

One especially important difference from a capital budgeting perspective is that the

depreciation methods allowed by GAAP differ from those allowed by the IRS.

o The straight-line depreciation method illustrated earlier in this chapter in

the NASCAR racetrack example is allowed by GAAP and is often used for

financial reporting.

o An “accelerated” method of depreciation, called the Modified Accelerated

Cost Recovery System (MACRS), has been in use for U.S. federal tax

calculations since the Tax Reform Act of 1986 went into effect.

MACRS thus enables a firm to deduct depreciation charges sooner,

thereby realizing the tax savings sooner and increasing the present

value of the tax savings.

D.

Computing the Terminal-Year FCF

•

The FCF in the last, or terminal, year of a project often includes cash flows that are

not typically included in the calculations for other years.

o For instance, in the final year of a project, the assets acquired during the

life of the project may be sold and the working capital that has been

invested may be recovered.

Add WC = Change in cash and cash equivalents + Change in

accounts receivable + Change in inventories – Change

in accounts payable.

o When an asset is expected to have a salvage value, we must include the

salvage value realized from the sale (net of any tax consequences) of the

asset and the impact of the sale on the firm’s taxes in the terminal-year

FCF calculations.

E.

Expected Cash Flows

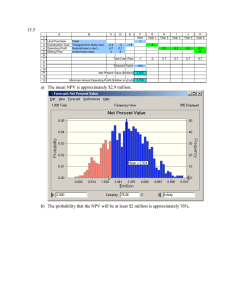

•

We are estimating when we forecast FCF in an NPV analysis.

o The expected FCF for a particular year equals the sum of the products of

the possible outcomes (FCFs) and the probabilities that those outcomes

will be realized.

11.3.1 Forecasting Free Cash Flows

A.

Cash Flows from Operations

•

To forecast incremental cash flows from operations we must forecast the

incremental net revenue, operating expenses, and depreciation and amortization

associated with the project, as well as the firm’s marginal tax rate

•

When forecasting operating expenses, analysts often distinguish between variable

costs and fixed costs

B.

Investment Cash Flows

•

We must consider two general classes of investments when calculating FCF:

incremental capital expenditures and incremental additions to working capital

1. Capital Expenditures

o Capital expenditure forecasts in an NPV analysis reflect the expected level

of investment during each year of the project’s life.

o Capital expenditures are typically required at the beginning of a project

2. Working Capital

o Cash flow forecasts in an NPV analysis include four working capital items:

1)cash and cash equivalents, 2) accounts receivable, 3) inventories, and 4)

accounts payable

11.4

Special Cases

A.

Projects with Different Lives

•

A problem that arises quite often in capital budgeting involves choosing

between two mutually exclusive investments where the investments have different

lives.

o

In a situation like this, we can effectively make the lives of the mowers

the same by assuming repeated investments over some identical period and

then comparing the NPVs of their costs.

o

A less cumbersome and more powerful method to handle the problem

is to compute the equivalent annual cost (EAC). The EAC can be calculated

as follows:

EACi = kNPVi [(1 + k)t / (1 + k)t –t 1]

( 1+ k )

EACi = k NPVi

t

−1

( 1+ k )

k is the opportunity cost of capital

NPVi is the normal NPV of the investment i

t is the life of the investment

(11.5)

EAC simply reflects the annuity that has the same present value as the

∆FCFs of an investment over the investment period we are considering.

B.

When to Harvest an Asset

•

The optimal time to harvest is the point in time at which the rate of increase in

cash flows, from period to period, is no longer greater than the cost of capital.

At this point in time, it becomes optimal to harvest the trees and invest the

proceeds in alternative investments that yield the opportunity cost of capital.

C.

When to Replace an Existing Asset

•

Two fundamental questions: Do the benefits of replacing the existing asset exceed

the costs, and, if they do not now, when will they?

•

Solving this problem is simply a matter of computing the EAC for the new asset

and comparing it with the annual cash inflows from the old asset.

D.

The Cost of Using an Existing Asset

•

The third rule of calculating incremental after-tax cash flows is to include all

opportunity costs that are not always directly observable.

o Sometimes they have to be computed by first figuring the EAC for a given set

of cash flows and then adjusting the EAC by the appropriate discount rate and

time, if the EAC is not in present value form.

II.

Suggested and Alternative Approaches to the Material

This is a very important chapter for all students. Finance majors will need the basic capital budgeting

concepts introduced here for their more advanced course work, whereas nonmajors will require a

basic foundation for the material in their professional lives as they will undoubtedly be involved in

project analysis at some point in their careers. The chapter begins with a general framework for

capital budgeting, so that the overall approach to capital budgeting can be seen before proceeding to

the detailed aspects of the subject matter. Free cash flow (FCF) is then formally introduced, along

with individual subcalculations that make it up. The chapter includes a number of examples to

accompany the individual aspects of the material and finishes by introducing cases where the net

present value of the projects FCFs will require further adjustments.

Thorough coverage of the material is recommended before proceeding to the next chapter

where the tools are then applied further. As such, it may be necessary to allocate additional time for

this chapter as the material is central to Finance while it also incorporates a number of tools that were

learned in earlier chapters.

III. Summary of Learning Objectives

1. Explain why incremental after-tax cash flows are relevant in evaluating a project, and be

able to calculate them for a project.

The incremental after-tax cash flows, also called the incremental free cash flows (FCFs), for a

project equal the expected change in the total after-tax cash flows of the firm if the project is

adopted. The impact of a project on the firm’s total cash flows is the appropriate measure of cash

flows because these are the cash flows that reflect all of the costs and benefits from the project

and only the costs and benefits from the project. The incremental after-tax cash flows are

calculated using Equation 11.2. The calculation is also illustrated in Exhibit 11.1.

2. List and explain the five general rules for incremental after-tax free cash flow calculations

and why cash flows stated in nominal (real) dollars should be discounted using a nominal

(real) discount rate.

The five general rules are:

Rule 1:

Include cash flows and only cash flows in your calculations. Stockholders only care

about the impact of a project on the firm’s cash flows.

Rule 2:

Include the impact of the project on cash flows from other product lines. If a project

affects the cash flows from other projects, we must take this fact into account in NPV

analysis in order to fully capture the impact of the project on the firm’s total cash

flows.

Rule 3:

Include all opportunity costs. If an asset is used for a project, the relevant cost for that

asset is the value that could be realized from its most valuable alternative use. By

including this cost in the NPV analysis, we capture the change in the firm’s cash flows

that is attributable to the use of this asset for the project.

Rule 4:

Forget sunk costs. The only costs that matter are those to be incurred from this point

on.

Rule 5:

Include only after-tax cash flows in the cash flow calculations. Since stockholders

receive cash flows after taxes have been paid, they are only concerned about after-tax

cash flows.

Since a nominal rate reflects both the expected rate of inflation and a real return, we would be

overadjusting for inflation if we discounted a real cash flow with a nominal rate. Similarly, if we

discounted a nominal cash flow using a real discount rate, we would be undercompensating for

expected inflation in the discounting process. This is why we discount nominal cash flows using

only a nominal discount rate and we discount real cash flows using only a real discount rate.

3. Describe how distinguishing between variable and fixed costs can be useful in forecasting

operating expenses.

Variable costs vary directly with the number of units sold, while fixed costs do not. When

forecasting operating expenses, it is often useful to treat variable and fixed costs separately. We

can forecast variable costs by multiplying unit variable costs by the number of units sold. Fixed

costs are more accurately based on the specific characteristics of those costs, rather than as a

function of sales. Separating fixed costs from the variable also makes it easier to identify the

factors that will cause them to change over time and therefore easier to forecast them.

4. Explain the concept of equivalent annual cost, and be able to use it to compare projects with

unequal lives, decide when to replace an existing asset, and calculate the opportunity cost of

using an existing asset.

The equivalent annual cost (EAC) is the annualized cost of an investment that is stated in nominal

dollars. In other words, it is the annual payment from an annuity that has the same NPV and the

same life as the project. Since it is a measure of the annual cost or cash inflow from a project, the

EAC for one project can be compared directly with the EAC from another project, regardless of

the lives of those two projects. Applications of the EAC concept are presented in Section 11.4.

5.

Determine the appropriate time to harvest an asset. The appropriate time to harvest an

asset is that point in time where harvesting the asset yields the largest present value, in today’s

dollars, of the project NPV.

IV. Summary of Key Equations

Equation

Description

Formula

11.1

Incremental free cash

flow definition

FCFProject = FCFFirm with project – FCFFirm without project

11.2

Incremental free dash

flow calculation

FCF = [(Revenue – Op Exp – D&A) x (1 – t)] + D&A – Cap Ex – Add WC

11.3

Inflation and real

components of cost of

capital

11.4

Incremental additions to

working capital

11.5

Equivalent annual cost

1 + k = (1 + ∆Pe) x (1 + r)

Add WC = Change in cash and cash equivalents + Change in

accounts receivable + Change in inventories –

Change in accounts payable

EACi = kNPVi [(1 + k)t / (1 + k)t – 1]

V.

Before You Go On Questions and Answers

Section 11.1

1. Why do we care about incremental cash flows at the firm level when we evaluate a project?

We care about incremental cash flows at the firm level because they reflect the impact of the

project on the total cash flows that the firm produces. This is what the stockholders care about.

The difference between the present value of the expected cash flows from the firm with the

project and the present value of the expected cash flows from the firm without the project is

precisely what the NPV of a project is. Our NPV estimate will be incorrect if we do not account

for all of the incremental cash flows at the firm level.

2. Why is D&A first subtracted and then added back in FCF calculations?

By subtracting D&A, calculating the tax obligation, and then adding back D&A, we are

accounting for the fact that D&A is a noncash charge that reduces the firm’s tax obligation by the

product of D&A and the tax rate (D&A x t). If we did not do this, we would overstate the tax

obligation and understate FCF.

3. What types of investments should be included in FCF calculations?

All investments directly associated with the project should be included in FCF calculations. These

can include both investments in tangible and intangible assets. They can also include investments

in additions to working capital, such as for the credit a firm extends to its customers and

inventories.

Section 11.2

1. What are the five general rules for calculating FCF?

(1) Include cash flows and only cash flows in your calculations.

(2) Include the impact of the project on cash flows from other product lines.

(3) Include all opportunity costs.

(4) Forget sunk costs.

(5) Include only after-tax cash flows in the cash flow calculations.

2. What is the difference between nominal and real dollars? Why is it important not to mix them

in an NPV analysis?

When most people talk about dollar amounts, they are referring to nominal dollars. Nominal

dollars do not take into account changes in purchasing power. Real dollars are dollar amounts that

are adjusted for changes in purchasing power. For example, 100 real dollars have the same

purchasing power whether they are received today or at some future date. It is important not to

mix nominal and real dollars in an NPV analysis because the discount rate is either a nominal

rate, which is used to discount nominal dollars, or a real rate, which is used to discount real

dollars. Since the discount rate must be either a nominal rate or a real rate, if real and nominal

dollars are mixed in an NPV analysis, the NPV will be calculated incorrectly.

3. What is a progressive tax system? What is the difference between a firm’s marginal and

average tax rates?

A progressive tax system is one in which the marginal tax rate at low levels of income is lower

than the marginal tax rate at high levels of income. A firm’s marginal tax rate is the rate that it

pays on the last dollar earned while the average tax rate is the average rate paid on the firm’s total

earnings (tax paid divided by taxable income).

4. How can FCF in the terminal year of a project’s life differ from FCF in the other years?

FCF in the terminal year can differ from FCF in other years in several ways. The terminal year

cash flows can include cash flows from the asset sales, including the actual proceeds from the

sales themselves and taxes due or received if there is a gain or loss on the sale. Terminal year

cash flows can also include cash flows associated with recovery of working capital.

5. Why is it important to understand that cash flow forecasts in an NPV analysis are expected

values?

It is important to recognize that we are forecasting expected cash flows in an NPV analysis

because uncertainties regarding project cash flows that are unique to the project should be

reflected in the cash flow forecasts.

Section 11.3

1. What is the difference between variable and fixed costs, and what are examples of each?

Variable costs vary directly with unit sales. Fixed costs do not vary with unit sales. For an

example of each, see the video game player scenario on page 379. Variable costs are those

associated with purchasing the components for the player, the labor required, and sales and

marketing. These costs will vary according to the number of units produced. Fixed costs are those

associated with assembly space, and administrative expenses.

2. How are working capital items forecast? Why are accounts receivable typically forecast as a

percentage of revenue and accounts payable, and inventories as percentages of the cost of good

sold?

Working capital items are forecast using 1) cash and cash equivalents, 2) accounts receivable, 3)

inventories, and 4) accounts payable

Inventories are forecast as a percentage of the cost of goods sold because the COGS represent a

measure of the amount of money invested in inventories. Accounts payable are forecast this way

because the COGS is a measure of the amount of money actually owed to suppliers.

Section 11.4

1. When can we not simply compare the NPVs of two mutually exclusive projects?

If we expect to replace at least one of the projects at the end of its life, we cannot simply compare

the NPVs. Doing so would ignore the subsequent investment(s). You can only directly compare

the NPVs of mutually exclusive projects under one condition—that is, if you expect to terminate

the project that is chosen (e.g., sell the lawn mower) on or before the end of the life of the shorterlived project.

2. How do we decide when to harvest an asset?

We choose the harvest date that maximizes the NPV of the asset. To identify this date, we

compare the NPVs expected from harvesting the asset for each of the feasible harvest dates. The

best date to harvest the asset is the date that produces the largest NPV, once the NPVs for all of

the alternative harvest dates have been discounted to the same point in time.

3. Under what circumstance would you replace an old machine that is still operating with a new

one?

You should replace the old machine when the EAC of the new machine is lower than the EAC of

the old machine (if revenues are the same for both machines) or when the annualized cash inflow

from the replacement is greater.

VI. Self Study Problems

11.1

Explain why the announcement of a new investment is usually accompanied by a change in

the firm’s stock price.

Solution:

A firm’s investments cause changes in its future after-tax cash flows and stockholders are the

residual claimants (owners) of those cash flows. Therefore, the stock price should increase

when stockholders expect an investment to have a positive NPV, and decrease when it is

expected to have a negative NPV.

11.2

In calculating the NPV of a project, should we use all of the cash flows associated with the

project, or incremental cash flows of the project? Why?

Solution:

We should use incremental cash flows of the project. Incremental cash flows reflect the

amount by which the firm’s total cash flows will change if the project is adopted. In other

words, incremental cash flows represent the net difference in cash revenues, costs, and

investment outlays at the firm level with and without the project, which is precisely what the

stockholders care about.

11.3

You are considering opening another restaurant in the food chain of TexasBurgers. The new

restaurant will have annual revenue of $300,000 and operating expenses of $150,000. The

annual depreciation and amortization for the assets used in the restaurant will equal $50,000.

An annual capital expenditure of $10,000 will be required to offset wear-and-tear on the

assets used in the restaurant, but no additions to working capital will be required. The

marginal tax rate will be 40 percent. Calculate the incremental annual free cash flow for the

project

Solution:

The incremental annual free cash flow is calculated as:

FCF = ($300,000-$150,000-$50,000) x (1-0.4) + $50,000-$10,000 = $100,000

11.4

Sunglass Heaven, Inc., is launching a new store in a shopping mall in Houston. The store’s

annual revenue depends on Houston’s weather conditions in the summer. The annual revenue

will be $240,000 in a sizzling summer, with probability of 0.3; $80,000 in a cool summer,

with probability of 0.2; and $150,000 in a normal summer, with probability of 0.5. What is the

expected annual revenue of the store?

Solution:

The expected annual revenue is:

(0.3 x $240,000) + (0.2 x $80,000) + (0.5 x $150,000) = $163,000

11.5

Sprigg Lane needs to purchase a new central air-conditioning system for a plant. There are

two choices. The first system costs $50,000 and is expected to last 10 years, and the second

system costs $72,000 and is expected to last 15 years. Assume that the opportunity cost of

capital is 10 percent. Which air-conditioning system should you purchase?

Solution:

The equivalent annual cost for each system is:

EAC1 = (0.1)($50,000)[((1.1)10)/((1.1)10-1)] = $8,137.27

EAC2 = (0.1)($72,000)[((1.1)15)/((1.1)15-1)] = $9,466.11

Therefore Sprigg Lane should purchase the first one.

VII. Critical Thinking Questions

11.1

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: given the techniques discussed in this

chapter? We can estimate future cash flows precisely and obtain an exact value for the NPV

of an investment.

The statement is not true. Given the nature of the real business world, it is almost certain that

the cash flows generated by a project will differ from the forecasts used to decide whether to

proceed with the project. However, techniques discussed in this chapter provide an important

and useful framework that helps minimize errors and ensures that forecasts are internally

consistent.

11.2

What are the differences between forecasted cash flows used in capital budgeting calculations

and past accounting earnings?

Cash flows used in capital budgeting calculations are forward looking; they are incremental

after-tax cash flows based on forecast. Accounting earnings are backward looking; they

represent a record of past performance and may not accurately reflect cash flows.

11.3

Suppose that FRA Corporation already has divisions in both Dallas and Houston. FRA is now

considering setting up a third division in Austin. This expansion will require one senior

manager from Dallas and one from Houston to relocate to Austin. Ignore relocation expenses.

Is their annual compensation relevant to the decision to expand?

The annual compensations of existing senior managers are not incremental to the new

investment and therefore are not relevant for capital budgeting analysis. This is consistent

with our Rule 1 for incremental cash flow calculations: Include cash flows and only cash

flows; do not include allocated costs unless they reflect cash flows.

11.4

MusicHeaven, Inc., is a producer of MP3 players which currently have either 20 gigabytes or

30 gigabytes of storage. Now the company is considering launching a new production line

making mini MP3 players with 5 gigabytes of storage. Analysts forecast that your company

will be able to sell 1 million such mini MP3 players if the investment is taken. In making the

investment decision, discuss what the company should consider other than the sales of the

mini MP3 players.

The company’s launch of the new mini MP3 players may reduce its current sales of MP3

players of bigger storage. This impact has to be considered. This is consistent with our Rule 2

for incremental cash flow calculations: Include the impact of the project on cash flows from

other product lines.

11.5

QualityLiving Trust is a real estate investment company that builds and remodels apartment

buildings in northern California. It is currently considering remodeling a few idle buildings in

its possession into luxury apartment buildings in San Jose. The company bought those

buildings eight months ago. How should the market value of the buildings be treated in

evaluating this project?

Although the buildings are not currently in use, the company can sell them at their market

value rather than remodel them into apartments. Therefore, the market value of the buildings

is the opportunity cost of the project and should be considered as cash outflow in the

investment decision. This is consistent with our Rule 3 for incremental cash flow calculations:

Include all opportunity costs.

11.6

High-End Fashions, Inc., bought a production line of ankle-length skirts last year at a cost of

$500,000. This year, however, miniskirts are hot in the market and ankle-length skirts are

completely out of fashion. High-End has the option to rebuild the production line and use it to

produce miniskirts, with a cost of $300,000 and expected revenue of $700,000. How should

the company treat the cost of $500,000 of the old production line in evaluating the rebuilding

plan?

The cost of the old production line occurred in the past. It cannot be changed whether or not

the company rebuilds it into the miniskirt production line. Therefore, High-End should not

consider the cost of $500,000. This is consistent with our Rule 4 for incremental cash flow

calculations: Forget sunk costs.

11.7

How is the MACRS depreciation method under IRS rules different from that under GAAP

rules? What is the implication of incremental after-tax cash flows from firms’ investments?

GAAP allows the straight-line depreciation method. In contrast, an “accelerated” method of

depreciation, Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS), has been used for U.S.

federal tax calculations. The advantage of MACRS, relative to straight-line depreciation, is

that it enables a firm to deduct depreciation changes sooner, thereby realizing the tax saving

sooner and increasing the present value of the tax savings.

11.8

Explain the difference between marginal and average tax rates, and identify which of these

rates is used in capital budgeting and why.

The marginal tax rate is the rate paid on the next dollar earned. The average tax rate is the

dollar value of total taxes paid divided by total income. The marginal tax rate is the

appropriate rate to use in capital budgeting analysis because this is the tax rate that will be

paid on the incremental income earned by the project.

11.9

When two mutually exclusive projects have different lives, how should we make the capital

budgeting decision? What is the underlying assumption in this method?

When we choose from mutually exclusive projects with different lives, instead of electing the

project with higher NPV or lower net present value of costs, we should choose the project

with higher Equivalent Annual Revenue or lower Equivalent Annual Cost. The underlying

assumption is that we will continue to operate with the same equivalent annual revenue or

equivalent annual cost in the future.

11.10 What is the opportunity cost of using an existing asset? Give an example of the opportunity

cost of using the excess capacity of a machine.

The opportunity cost of using an existing asset in a project is the present value of the change

in the firm’s cash flows that is attributed to the fact that this asset is being used in the project.

For example, by using the excess capacity of a machine, you may accelerate the wear-andtear of the machine and hence will need to replace it sooner. The present value of the added

annualized costs is the opportunity cost of using the excess capacity.

11.11 You are providing financial advice to a shrimp farmer who will be harvesting his last crop of

farm-raised shrimp. His current shrimp crop is very young and will therefore grow and

become more valuable as their weight increases. Describe how you would determine the

appropriate time to harvest the entire crop of shrimp.

Assuming that the price of shrimp is directly (and linearly) related to the weight of the

shrimp, then the optimal point in time to harvest the shrimp would be where the rate of

weight increase is no longer greater than the opportunity cost of capital for the shrimp farmer.

Alternatively, the appropriate time is when the value increase of the shrimp is no longer

greater than the opportunity cost of capital.

VIII.

BASIC

Questions and Problems

11.1 Calculating project cash flows: Why do we use forecasted cash flows instead of forecasted

accounting earnings in estimating the NPV of a project?

Solution:

Accounting earnings can differ from cash flows for a number of reasons, making accounting

earnings an unreliable measure of the costs and benefits of a project. For example, ease of

manipulating earnings components such as accounts receivable and depreciation may result in

distorted estimation of capital budgeting; using forecasted cash flows eliminates such

possibilities. In addition, because there is time value of money, cash flows better reflect the

actual available funds to be distributed to shareholders at each point in time.

11.2 The FCF calculation: How do we calculate incremental free cash flow from the forecasted

earnings of a project? What are the common adjustment items?

Solution:

We need to adjust for the depreciation and amortization tax shield, capital expenditures, and

changes in working capital (including receivables and payables).

11.3 The FCF calculation: How do we adjust for depreciation when we calculate incremental aftertax cash flow from EBITDA? What is the intuition for the adjustment?

Solution:

There are two ways to adjust for depreciation: (1) subtract depreciation from EBITDA,

multiply it by (1 – tax rate), and then add depreciation back; (2) add the tax shield from

depreciation (depreciation multiplied by tax rate) to revenue. These two methods yield the

same results. The intuition is that although depreciation itself is not a cash flow inflow or

outflow, increase in depreciation will result in a decrease in taxable income. This saving on

tax is treated as cash inflow in calculating incremental after-tax cash flows.

11.4

Nominal versus real cash flows: What is the difference between nominal and real dollars?

Which rate of return should we use to discount each type of these cash flows in the future?

Solution:

Nominal dollars are dollars stated as we usually think of them, without any adjustment for

changes in purchasing power over time. Real dollars are dollars stated so that their purchasing

power remains constant. We should use nominal rate of return to discount future nominal

dollars and real rate of return to discount future real dollars. By doing this, we will get

meaningful present values in today’s dollars and purchasing power.

11.5

Taxes and depreciation: What is the difference between the average tax rate and the

marginal tax rate? Which one should we use in calculating the incremental after-tax cash

flows?

Solution:

In a progressive tax system, the marginal tax rate is different from the average tax rate. The

average tax rate is the total amount of tax divided by total amount of money earned, while the

marginal tax rate is the rate paid on the last dollar earned. Since a firm already pays taxes, the

appropriate tax rate used for the firm’s new project is the tax rate that the firm will pay on any

additional profits that are earned because the project is adopted. Therefore, we use the

marginal tax rate in calculating incremental after-tax cash flows.

11.6

Computing terminal-year FCF: Five years ago, a pharmaceutical company bought a

machine that produces pain-reliever medicine at a cost of $2 million. The machine has been

depreciated over the past five years, and the current book value is $800,000. The company

decides to sell the machine now at its market price of $1 million. The marginal tax rate is 30

percent. What are the relevant cash flows? How do they change if the market price of the

machine is $600,000 instead?

Solution:

The relevant cash flows include the sale price of the machine, as well as the tax on the capital

gain:

1,000,000 – 0.3(1,000,000 – 800,000) = $940,000

When the market price of the machine is changed to $600,000, the relevant cash flows

include the sale price and tax saving on capital loss:

6,000,000 + 0.3(800,000 – 600,000) = $6,060,000

11.7

Cash flows from operations: What are variable costs and fixed costs? What are some

examples of each? How are these costs estimated in forecasting operating expenses?

Solution:

Variable costs vary directly with unit sales. Fixed costs do not vary with unit sales. For an

example of each, see the video game player scenario on page 379. Variable costs are those

associated with purchasing the components for the player, the labor required, and sales and

marketing. These costs will vary according to the number of units produced. Fixed costs are those

associated with assembly space, and administrative expenses.

11.8

Investment cash flows: Six Twelve is considering opening up a new convenience store in

downtown New York City. The expected annual revenue is $800,000. To estimate the increase

in working capital, analysts estimate the ratio of cash and cash equivalents to revenue to be

0.03, and the ratio of receivables to revenue to be 0.05 in the same industry. What are the

incremental cash flows related to working capital when the store is opened?

Solution:

Cash flow related to working capital in year0 = $(800,000)*(0.03 + 0.05) = $(64,000)

11.9

Investment cash flows: Keswick Supply Company wants to set up a division providing copy

and fax business. Customers will be given 20 days to pay for such services. The annual

revenue of the division is estimated to be $25,000. What is the incremental cash flow

associated with accounts receivable?

Solution:

The customers are expected to take 20 days to pay, and the average accounts receivable

balance will be (20days/365days/year)*100%*25,000 = 5.48%*25,000 = $1,370.

Alternatively, the average daily credit sale is $25,000 / 365 = $68.49, and it takes 20 days, on

average, to collect the sale. Therefore, 20 x $68.49 = $1,369.86, or about $1,370.

11.10 Expected cash flows: Define expected cash flows and explain why this concept is important

in evaluating projects.

Solution:

Expected cash flows are probability-weighted averages of the future cash flows generated by

a project under alternative scenarios. In the real business world there are a lot of uncertainties.

Future cash flows may vary across different states of the world. It is not possible to estimate a

unique number of cash flow for all states. We can estimate the expected cash flows across

different states and use that as an estimation of future cash flows. The cash flows that are

discounted in an NPV analysis are the expected incremental cash flows the project will

produce.

11.11 Projects with different lives: Explain the concept of equivalent annual cost and how it is

used to compare projects with different lives.

Solution:

The equivalent annual cost (EAC) is the annualized cost of an investment stated in nominal

dollars. In other words, it is the annual payment from an annuity with a life equal to that of a

project that has the same NPV as the project. Since it is a measure of the annual cost or cash

inflow from a project, the EAC for one project can be compared directly with the EAC from

another project, regardless of the lives of those two projects.

11.12 Replace an existing asset: Explain how we decide the optimal time to replace an existing

asset with a new one.

Solution:

The optimal time to replace an existing asset with a new one is if the benefits of replacing the

machine exceed the costs.

INTERMEDIATE

11.13 Nominal versus real cash flows: You are buying a sofa. You will pay $200 today and make

three consecutive annual payments of $300 in the future. The real rate of return is 10 percent,

and the expected inflation rate is 4 percent. What is the actual price of the sofa?

Solution:

We can calculate it in two different ways:

(1)

Use nominal dollars and nominal rate of return:

Nominal rate of return = (1 + 10%)*(1 + 4%)-1 = 14.4%

Price = 200 + 300 / (1 + 14.4%) + 300/(1 + 14.4%)2 + 300 / (1 + 14.4%)3 = 891.84

(2)

Use real dollars and a real rate of return:

Real annual payments are: 300 / (1 + 4%) = 288.46, 300 / (1 + 4%)2 = 277.37, and

300 / (1 + 4%)3 = 266.70

Price = 200 + 288.46/(1 + 10%) + 277.37/(1 + 10.4%)2+266.7 / (1+10.4%)3 =891.84

Note that we get identical results as long as we are consistent in using nominal or real cash

flows and corresponding discount rates.

11.14 Nominal versus real cash flows: You are graduating in two years. You want to invest your

current savings of $5,000 in bonds for the down payment on a new car when you graduate and

start to work. You can invest the money in either Bond A, a two-year bond with a 3 percent

annual interest rate, or Bond B, an inflation-indexed two-year bond paying 1 percent real

interest above the inflation rate (assume this bond makes annual interest payments). The

inflation rate over the next two years is expected to be 1.5 percent. Assume that both bonds

are default free and have the same market price. Which one should you invest in?

Solution:

The nominal interest rate is 3 percent for bond A, and (1 + 1%)*(1 +1.5%) –1 = 2.52% for the

inflation-indexed bond B. You should invest in bond A.

11.15 Marginal and average tax rates: Given the U.S. Corporate Tax Rate Schedule in Exhibit

11.5, what is the marginal tax rate and average tax rate of a corporation that generates a

taxable income of $12 million in 2007?

Solution:

The marginal tax rate is 35 percent.

The total tax payable is 3,400,000 + (12,000,000-10,000,000)*35% = $4,100,000 Therefore

the average tax rate = 4,100,000 / 12,000,000 = 34.2%

11.16 Investment cash flows: Healthy Potions, Inc., is considering investing in a new production

line of eye drops. Other than investing in the equipment, the company needs to increase its cash

and cash equivalents by $10,000, increase the level of inventory by $30,000, increase accounts

receivable by $25,000, and increase accounts payable by $5,000 at the beginning of the

investment. Healthy Potions will recover these changes in working capital at the end of the

project 10 years later. Assume the appropriate discount rate to be 12 percent. What are the

relevant cash flows given the above information?

Solution:

The relevant cash flow related to working capital at the beginning of the project is:

$(10,000)-$30,000-$25,000 + $5,000 = $(60,000)

The present value of relevant cash flow related to working capital at the end of the project is:

60,000 / (1 + 12%)10 = $19,318.39

11.17 Cash flows from operations: Given the soaring price of gasoline, Ford is considering

introducing a new production line of gas-electric hybrid sedans. The expected annual sales

number of such hybrid cars is 30,000; the price is $22,000 per car. Variable costs of

production amount to $10,000 per car. The fixed overhead including salary of top executives

is $80 million per year. However, the introduction of the hybrid sedan will decrease Ford’s

sales of regular sedans by 10,000 cars per year; the regular sedans have a unit price of $20,000

and unit variable cost of $12,000, and fixed costs of $250,000 per year. Depreciation costs of

the production plant are $50,000 per year. The marginal tax rate is 40 percent. What is the

incremental annual cash flow from operations?

Solution:

Step One: Revenue: $22,000 x 30,000 machines =$660,000,000

Step Two: Op Exp: $10,000 x 30,000 machines = $300,000,000, plus lost net revenue from

regular sedans = ($20,000 – $12,000) x 10,000 = $80,000,000; total Op Exp =

$380,000,000

Step Three: D&A: $50,000

Step Four: Plug information into the text book template as below.

=

=

x

=

+

=

=

ΔNR

ΔOpEx

ΔEBITDA

ΔD&A

ΔEBIT

(1-t)

ΔNOPAT

ΔD&A

ΔCFO

ΔCapEx

ΔAWC

ΔFCF

660,000,000

-380,000,000

280,000,000

-50,000

279,950,000

0.60

167,970,000

50,000

168,020,000

0

0

168,020,000

Alternatively, the incremental annual cash flow from operations is:

((22,000-10,000)*30,000-(20,000-12,000)*10,000)*(1-0.4) + 50,000*0.4 = 168,020,000

Note that the fixed costs are not included in the incremental cash flows calculations, since

they exist regardless of the hybrid sedan investment.

11.18 FCF and NPV for a project: Archers Daniels Midland Company is considering buying a

new farm that it plans to operate for 10 years. The farm will require an initial investment of

$12 million. The investment will consist of $2 million for land and $10 million for trucks and

other equipments. The land, all trucks, and all other equipment are expected to be sold at the

end of 10 years at a price of $5 million, $2 million above book value. The farm is expected to

produce revenue of $2 million each year, and annual cash flow from operates equals $1.8

million. The marginal tax rate is 35 percent, and the appropriate discount rate is 10 percent.

Calculate the NPV of this investment.

Solution:

Cash flow of investment in year 0 is: $(12,000,000)

PV of annual investment year 1 to 10 is found using the present value factor for an annuity:

Payment * ( 1 – {1 / (1 + i)n}) / i)

$(1,000,000)( 1 – {1 / (1.1)10}) / 0.1) = $(6,144,567.11)

PV of sales and tax on capital gain in year 10 is:

(5,000,000-[2,000,000*0.35]) / (1.1)10 = 1,657,836.15

Therefore, PV of investment cash flows = $(16,486,730.97)

The company should not buy the farm.

11.19 Projects with different lives: You are starting a family pizza restaurant and need to buy a

motorcycle for delivery orders. You have two models in mind. Model A costs $9,000 and is

expected to run for 6 years; model B is more expensive, with a price of $14,000 and an

expected life of 10 years. The annual maintenance costs are $800 for model A and $700 for

model B. Assume that the opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent. Which one should you

buy?

Solution:

You need first calculate the NPV of costs for each of the motorcycles:

NPVA = 9,000 + 800*(((1.1)6-1) / ((1.1)6*0.1)) = 12,484.21

NPVB = 14,000 + 700*(((1.1)10-1) / ((1.1)10*0.1)) = 18,301.20

Then you need to calculate the EAC of each model:

EACA = 12,484.21*10%*((1.1)6) / ((1.1)6-1) = 2,866.47

EACB = 18,301.20*10%*((1.1)10) / ((1.1)10-1) = 2,978.44

Therefore you should buy model A.

11.20 When to harvest an asset: Predator LLC, a leveraged buyout specialist, recently bought a

company and want to decide the optimal time to sell it. The partner in charge of this

investment has estimated the after-tax cash flows at different times as follows: $700,000 if

sold one year later; $1,000,000 if sold two years later; $1,200,000 if sold three years later; and

$1,300,000 if sold four years later. The opportunity cost of capital is 12 percent. When should

Predator sell the company? Why?

Solution:

The NPV of each choice is:

NPV1 = 700,000 / (1.12)1 = 625,000

NPV2 = 1,000,000 / (1.12)2 = 797,194

NPV3 = 1,200,000 / (1.12)3 = 854,136

NPV4 = 1,300,000 / (1.12)4 =826,174

Therefore you should sell the company three years later.

11.21 Replace an existing asset: Bell Mountain Vineyards is considering updating its current

accounting system with a high-end electronic system. While the new accounting system

would save the company money, the cost of the system continues to decline. Bell Mountain’s

opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent, and the costs and values of future savings choices

are as follows:

Year

Cost

Value of Future Savings (at time of purchase)

0

$5,000

$7,000

1

4,500

7,000

2

4,000

7,000

3

3,600

7,000

4

3,300

7,000

5

3,100

7,000

When should Bell Mountain buy the new accounting system?

Solution:

The NPV of each choice is:

NPV0 = 2,000

NPV1 = 2,500 / (1.1)1 = 2,275

NPV2 = 3,000 / (1.1)2 = 2,479

NPV3 = 3,400 /(1.1)3 =2,554

NPV4 = 3,700 / (1.1)4 = 2,527

NPV5 = 3,900 / (1.1)5 = 2,422

Therefore the company should buy it in year 3.

11.22 Replace an existing asset: You have a 1993 Nissan that is expected to run for another three

years, but you are considering buying a new Hyundai in a few years. You will donate the old

Nissan to Goodwill when you buy the new car. The annual maintenance cost is $1,500 per

year for the old Nissan and $200 for the new Hyundai. The price of your favorite Hyundai

model is $18,000; it is expected to run for 15 years. Your opportunity cost of capital is 3

percent. Ignore taxes. When should you buy the new Hyundai?

Solution:

NPV of cost of the new car is:

NPVHyundai= 18,000 + 200*(((1.03)15-1) / ((1.03)15*0.03)) = 20,387.59

EAC of the new car is:

EACHyundai = 20,387.59*0.03*((1.03)15) / ((1.03)15-1) = 1,707.8 > 1,500

Therefore, you should drive the 1993 Nissan for three more years and then buy a new

Hyundai.

11.23 Replace an existing asset: Assume that you are considering replacing your old Nissan with a

new Hyundai, as in the previous problem. However, the annual maintenance cost of the old

Nissan increases as time goes by. It is $1,200 in the first year, $1,500 in the second year, and

$1,800 in the third year. When should you replace it with the new Hyundai in this case?

Solution:

The EAC of the Hyundai remains at $1,707.8, as calculated in the previous problem.

Compare this amount with the annual maintenance costs of the Nissan and you will see that in

year 2 it is cheaper to drive the Nissan, but in year 3 it is cheaper to drive the Hyundai.

Therefore, the optimal time to replace the old car is at the end of year 2.

11.24 When to harvest an existing asset: Anaconda Manufacturing Company currently own a mine

that is known to contain a known amount of gold. Since Anaconda does not have any goldmining expertise, the company plans to sell the entire mine and base the selling price on a

fixed multiple of the spot price for gold at the time of the sale. Analysts at Anaconda have

forecast the price spot for gold and have determined that the price will increase by 14 percent,

12 percent, 9 percent, and 6 percent during the next one, two, three, and four years,

respectively. If Anaconda’s opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent, what is the optimal time

for Anaconda to sell the mine?

Solution:

The rate of gold price appreciation is greater than the opportunity cost of capital for the next

two years and then it drops below the opportunity cost of capital. Therefore, Anaconda should

sell the gold at the beginning of the third year (or at the end of the second year).

11.25 Replace an existing asset: You are thinking about delivering pizzas in your spare time. Since

you must use your own car to deliver the pizzas, you will wear out your current car one year

earlier, which is one year from today, than if you did not take on the delivery job. You

estimate that when you purchase a new car, regardless of when that occurs, you will pay

$20,000 for the car and it will last you five years. If your opportunity cost of capital is 7

percent, what is the opportunity cost of using your car to deliver pizzas?

Solution:

(1 + 0.07)5

EACNew CAr = .07 *$20,000 *

= $4,877.81

5

(1 + 0.07) − 1

Therefore, the opportunity cost of wearing out your car a year earlier is

NPVU sin g your car

ADVANCED

= −$4,877.81/(1.07)1 = $4,558,70

11.26 You are the CFO of SlimBody, Inc., a retailer of the exercise machine Slimbody6® and related

accessories. Your firm is considering opening up a new store in Los Angeles. The store will

have a life of 20 years. It will generate annual sales of 5,000 exercise machines, and the price

of each machine is $2,500. The annual sales of accessories will be $600,000, and the

operating expenses of running the store, including labor and rent, will amount to 50 percent of

the revenues concerning the exercise machines. The initial investment in the store will equal

$30 million and will be fully depreciated on a straight-line basis over the 20-year life of the

store. Your firm will need to invest $2 million in additional working capital immediately, and

recover it at the end of the investment. Your firm’s marginal tax rate is 30 percent. The

opportunity cost of opening up the store is 10 percent. What are the incremental cash flows

from this project at the beginning of the project as well as in years 1-19 and 20? Should you

approve it?

Solution:

Step One: Initial outlay = $30,000,000 + $2,000,000 (WC requirement) = $32,000,000

Step Two: ΔNR for years 1- 20: $2,500 x 5,000 machines = $12,500,000 plus $600,000 =

$13,100,000

Step Three: ΔOpExp for years 1- 20: $1,250 x 5,000 machines = $6,250,000

Step Four: ΔD&A for years 1- 20: $30,000,000 / 20 years = $1,500,000 / year

Step Five: Plug information into the text book template as below.

Step Six: Yr 20 recapture of WC requirements that were funded in year 0.

Yrs 1-19

ΔNR

ΔOpEx

ΔEBITDA

ΔD&A

ΔEBIT

(1-t)

ΔNOPAT

ΔD&A

ΔCFO

ΔCapEx

ΔAWC

ΔFCF

-30,000,000

-2,000,000

-32,000,000

13,100,000

-6250000

6,850,000

-1500000

5,350,000

0.7

3,745,000

1,500,000

5,245,000

0

0

5,245,000

Yr 20

13,100,000

-6250000

6,850,000

-1500000

5,350,000

0.7

3,745,000

1,500,000

5,245,000

0

2,000,000

7,245,000

Therefore the NPV of the project is:

NPV = -32,000,000+5,245,000*(((1.1)20-1)/ ((1.1)20*0.1))+2,000,000/(1.1)20

=14,483,370

You should approve the project since it has a positive NPV.

Alternative Solution:

Incremental cash flows in year 0 is:

FCF0 = -30,000,000-2,000,000= -32,000,000

Annual incremental cash flows through the life of the investment are:

FCFt = (2,500*2,500+600,000)*(1-0.3)+0.3*1,500,000 = 5 ,245,000

Additional incremental cash flows at the end of the project are:

2,000,000

Therefore the NPV of the project is:

NPV = -32,000,000+5,245,000*(((1.1)20-1)/ ((1.1)20*0.1))+2,000,000/(1.1)20

=14,483,370

You should approve the project since it has a positive NPV.

11.27 Rocky Mountain Lumber, Inc., is considering purchasing a new wood saw that costs $50,000.

The saw will generate revenues of $100,000 per year for five years. The cost of materials and

labor needed to generate these revenues will total $60,000 per year, and other cash expenses

will be $10,000 per year. The machine is expected to sell for $1,000 at the end of its five-year

life and will be depreciated on a straight-line basis over five years to zero. Rocky Mountain’s

tax rate is 34 percent, and its opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent. Should the company

purchase the saw? Explain why or why not.

Solution:

Step One: Initial outlay = $50,000

Step Two: ΔNR for years 1- 5: $100,000

Step Three: ΔOpExp for years 1- 5: $60,000 + $10,000 = $70,000

Step Four: ΔD&A for years 1- 5: $50,000 / 5 years = $10,000 / year

Step Five: Plug into the text book template as below.

Step Six: Yr 5: Capital recovery = $1,000 – (.34 x 1,000 gain on sale) = $660.

Yrs 1-4

ΔNR

ΔOpEx

ΔEBITDA

ΔD&A

ΔEBIT

(1-t)

ΔNOPAT

ΔD&A

ΔCFO

ΔCapEx

ΔAWC

ΔFCF

-50,000

0

-50,000

Yr 5

100,000

-70000

30,000

-10000

20,000

0.66

13,200

10,000

23,200

0

0

23,200

100,000

-70000

30,000

-10000

20,000

0.66

13,200

10,000

23,200

660

0

23,860

Therefore, NPV of investment is:

-50,000+23,200/(1.1)1+23,200/(1.1)2+23,200/(1.1)3+23,200/(1.1)4

+(23,200+660)/(1.1)5=$38,356

Therefore the company should buy the machine.

Alternatively:

The annual operating cash flows from year 1 to 5 are:

(100,000-60,000-10,000)*(1-0.34)+0.34*10,000=23,200

The after-tax terminal value in year 5 is:

1,000 -(.34)(1,000-0) = 660

Therefore, NPV of investment is:

-50,000+23,200/(1.1)1+23,200/(1.1)2+23,200/(1.1)3+23,200/(1.1)4

+(23,200+660)/(1.1)5=$38,356

Therefore the company should buy the machine.

11.28 A beauty product company is developing a new fragrance named Happy Forever. There is a

probability of 0.5 that consumers will love Happy Forever, and in this case, annual sales will

be 1 million bottles; a probability of 0.4 that consumers will find the smell acceptable and

annual sales will be 200,000 bottles; and a probability of 0.1 that consumers will find the

smell weird and annual sales will be only 50,000 bottles. The selling price is $38, and the

variable cost is $8 per bottle. There is a fixed production cost of $1 million per year, and

depreciation costs are $1.2 million. Assume that the marginal tax rate is 40 percent. What are

the expected annual incremental cash flows from the new fragrance?

Solution:

Step One: Expected sales units: (.5)1,000,000 + (.4)200,000 + (.1)50,000 = 585,000 units

Step Two: ΔNR: 585,000 units x $38 = $22,230,000

Step Three: ΔOpExp: 585,000 units x $8 + $1,000,000 = $5,680,000

Step Four: ΔD&A: $1,200,000

Step Five: Plug into the text book template as below.

=

=

x

=

+

=

=

ΔNR

ΔOpEx

ΔEBITDA

ΔD&A

ΔEBIT

(1-t)

ΔNOPAT

ΔD&A

ΔCFO

ΔCapEx

ΔAWC

ΔFCF

22,230,000

-5,680,000

16,550,000

-1,200,000

15,350,000

0.60

9,210,000

1,200,000

10,410,000

0

0

10,410,000

Alternatively, the expected annual incremental cash flows are:

(((0.5*1,000,000+0.4*200,000+0.1*50,000)*(38-8))-1,000,000)*(1-0.4)+1,200,000*0.4 =

10,410,000

11.29 Great Fit, Inc., is a company that makes clothing. The company has a product line that

produces women’s tops of regular sizes. The same machine could be used to produce petite

sizes as well. However, the life of the machines will be reduced from four more years to two

more years if the petite size production is added. The cost of identical machines with a life of

eight years is $2 million. Assume the opportunity cost of capital is 8 percent. What is the

opportunity cost of adding petite sizes?

Solution:

The opportunity cost is the incremental costs of the machine in year 3 and year 4 if petite

sizes are in production. The EAC of the machine is:

EAC=2,000,000*0.08*((1.08)8)/((1.08)8-1)=348,029.52

The present value of such cost in year 3 and year 4 is:

NPV=348,029.52/(1.08)3+348,029.52/(1.08)4=532,089.14

11.30 Biotech Partners LLC has been farming a new strain of radioactive-material-eating bacteria

that the electrical utility industry can use to help dispose of its nuclear waste. Two opposing

effects are affecting Biotech’s decision of when to harvest the bacteria. The bacteria are

currently growing at a 22 percent annual rate, but due to known competition from other top

firms, Biotech analysts estimate that the price for the bacteria will fluctuate according to the

scale below. If the opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent, then when should Biotech harvest

the entire bacteria colony at one time?

Year

Change in Price Due to Competition (5)

1

5%

2

-2

3

-8

4

-10

5

-15

6

-25

Solution:

Change in revenue:

Yr 1

(1.05)(1.22) = 1.2810 or 28.1%

Yr 2

(0.98)(1.22) = 1.1956 or 19.56%

Yr 3

(0.92)(1.22) = 1.1224 or 12.24%

Yr 4

(0.9)(1.22) = 1.0980 or 9.80%

Yr 5

(0.85)(1.22) = 1.037 or 3.70%

Yr 6

(0.75)(1.22) =- 0.9150 or -8.50%

Since the change in revenue is higher for the first two years, Biotech should sell its bacteria

colony at the beginning of the third year or at the end of the second year.

11.31 ACME manufacturing is considering replacing an existing production line with a new line

that has a greater output capacity and operates with less labor than the existing line. The new

line would cost $1 million, have a five-year life, and would be depreciated using MACRS

over three years. At the end of five years, the new line could be sold as scrap for $200,000 (in

year 5 dollars). Because the new line is more automated, it would require fewer operators,

resulting in a saving of $40,000 per year before tax and unadjusted for inflation (in today’s

dollars). Additional sales with the new machine are expected to result in additional net cash

inflows, before tax, of $60,000 per year (in today’s dollars). If ACME invests in the new line,

a one-time investment of $10,000 in additional working capital will be required. The tax rate

is 35 percent, the opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent, and the annual rate of inflation is 3

percent. What is the NPV of the new production line?

Solution:

(Revenue Op Exp)(1-t)

plus Tax x Deprec

minus Cap Exp

$1,000,000

plus tax on Salvage

minus Add WC

$66,950

$68,959

$71,027

$73,158

$116,655

$155,575

$51,835

$25,935

$75,353

$(200,000)

$(70,000)

$10,000

$(10,000)

Net Cash Flows

$(1,010,000)

$183,605

$224,534

$122,862

$99,093

$215,353

PV of Net Cash Flows

$(1,010,000)

$166,914

$185,565

$92,308

$67,682

$133,717

Net Present Value

$(363,814)

11.32 The alternative to investing in the new production line in Problem 11.31 is to overhaul the

existing line, which currently has both a book value and a salvage value of $0. It would cost

$300,000 to overhaul the existing line, but this expenditure would extend its useful life to five

years. The line would have a $0 salvage value at the end of five years. The overhaul outlay

would be capitalized and depreciated using MACRS over three years. Should ACME replace

or renovate the existing line?

(Revenue Op Ex)(1-t)

plus Tax x Deprec

minus Cap Exp

$34,997

$46,673

$15,551

$7,781

$300,000

plus tax on Salvage

minus Add WC

Net Cash Flows

$(300,000)

$34,997

$46,673

$15,551

$7,781

$0

PV of Net Cash Flows

$(300,000)

$31,815

$38,572

$11,683

$5,314

$0

Net Present Value

$(212,615)

NPVnew - NVPold

$(151,199)

Renovating the old line is less costly.

CFA Problems

11.33. FITCO is considering the purchase of new equipment. The equipment costs $350,000, and an

additional $110,000 is needed to install it. The equipment will be depreciated straight-line to

zero over a five-year life. The equipment will generate additional annual revenues of

$265,000, and it will have annual cash operating expenses of $83,000. The equipment will be

sold for $85,000 after five years. An inventory investment of $73,000 is required during the

life of the investment. FITCO is in the 40 percent tax bracket and its cost of capital is 10

percent. What is the project NPV?

A.

$47,818

B.

$63,658

C.

$80,189

D.

$97,449

Solution:

D is correct.

5

NPV = −533, 000 +

146, 000 124, 000

Outlay = FCInv + NWCInv – Sal0 + T(Sal0 –

B0)

Outlay = (350,000 + 110,000) + 73,000 – 0 + 0

= $533,000

The installed cost is $350,000 +

$110,000 = $460,000, so the

annual depreciation is $460,000/5

= $92,000. The annual after-tax

operating cash flow for Years 1–

5 is

CF = (S – C – D)(1 – T) + D = (265,000 –

83,000 – 92,000)(1 – 0.40) + 92,000 CF =

$146,000

The terminal year after-tax nonoperating cash flow in Year 5 is TNOCF =

Sal5 + NWCInv – T(Sal5 – B5) = 85,000

+ 73,000 – 0.40(85,000 – 0)

TNOCF = $124,000

The NPV is

t =1

11.34. After estimating a project’s NPV, the analyst is advised that the fixed capital outlay will be

revised upward by $100,000. The fixed capital outlay is depreciated straight-line over an

eight-year life. The tax rate is 40 percent and the required rate of return is 10 percent. No

changes in cash operating revenues, cash operating expenses, or salvage value are expected.

What is the effect on the project NPV?

A.

$100,000 decrease

B.

$73,325 decrease

C.

$59,988 decrease

D.

No change

Solution:

B is correct. The additional annual depreciation is $100,000/8 = $12,500. The depreciation

tax savings is 0.40 ($12,500) = $5,000. The change in project NPV is

−100, 000 +

8

t=1

5, 000

= −100, 000+ 26, 675= − $73, 325

t

(1.10)

11.35. When assembling the cash flows to calculate an NPV or IRR, the project’s after-tax interest

expenses should be subtracted from the cash flows for

A.

the NPV calculation, but not the IRR calculation.

B.

the IRR calculation, but not the NPV calculation.

C.

both the NPV calculation and the IRR calculation.

D.

neither the NPV calculation nor the IRR calculation.

Solution:

D is correct. Financing costs are not subtracted from the cash flows for either the NPV or the

IRR. The effects of financing costs are captured in the discount rate used.

Sample Test Problems

11.1

You purchased 100 shares of stocks of an oil company, TexasEnergy, Inc., at the price of

$50/share. The company has 1 million shares outstanding. Ten days later TexasEnergy

announced an investment in an oil field in east Texas. The probability of the investment being

successful and generating NPV of $10 million is 0.2; the probability of the investment will be

a failure and generate a negative NPV of negative $1 million is 0.8. How would you expect

the stock price to change upon the company’s announcement of the investment?

Solution:

The expected change in the stock price should be equal to the expected NPV of the project

divided by the number of shares outstanding. The expected NPV of the project is

0.2*10,000,000 + 0.8*(–1,000,000), such that:

Change in stock price = (0.2*10,000,000 + 0.8*(-1,000,000)) / 1,000,000 shares =

$1.2/share

Stock price of TexasEnergy, Inc., will increase by $1.20 upon the announcement of the

investment.

11.2

A chemical company is considering buying a magic fan for its plant. The magic fan is

expected to work forever and to help cool the machines in the plant and hence reduce their

maintenance costs by $4,000 per year. The cost of the fan is $30,000. The appropriate

discount rate is 10 percent, and the marginal tax rate is 40 percent. Should the company buy

the magic fan?

Solution:

The after-tax saving of maintenance costs is: $4,000*(1 – 40%) / 10% = $24,000, which is

less than the cost. Therefore the company should not buy the fan. If one fails to take into

consideration the tax effect on maintenance costs, the opposite conclusion will be made.

Therefore it is important to remember our Rule 5 for incremental cash flow calculations:

Include only after-tax cash flows.

11.3

Hogvertz Elvin Catering (HEC) is considering switching to a new Wonder Food Maker. Both

food makers will remain useful for the next ten years, but the new option will generate a

depreciation expense of $5,000 per year while the old food maker will generate a depreciation

expense of $4,000 per year. What is the after-tax cash flow effect from deprecation of

switching to the new food maker for HEC if the firm’s marginal tax rate is 40 percent and the

correct discount rate is 12 percent?

Solution:

Without the benefit of other information required in the cash flow calculation table, we must

isolate the cash flow effect of depreciation for a firm. We therefore find that we have a

deduction of D&A above the tax calculation line and an addition of D&A below the tax

calculation line. This means that the net yearly after-tax effect of depreciation and

amortization can be simplified to:

-(D&A)(1 – t) + (D&A) = – (D&A) + (D&A) t + (D&A) = (D&A) t

Using that result, we find that the net yearly effect of depreciation and amortization of cash

flow is:

(D&A) t = ( $5,000 – $4,000) x .4 = $400

and so the present value of the total after-tax cash flow effect from depreciation can be found

as follows:

$400 x (((1.12)10-1) / ((1.12)10*0.12)) = $400 x 5.650223 = 2,260.09

11.4

The Long-Term Financing Company has identified a new alternative project that is similar in

all respect to its current project except one. That is, the new project will reduce the need for

working capital by $10,000 during the 30-year life of the project. The firm’s cost of capital is

18 percent, and the marginal corporate tax rate for the firm is 34 percent. What is the after-tax

present value of this new alternative project?

Solution:

Because working capital has no effect on the income statement of the firm, there are no tax

effects from the two cash flows associated with the working capital change. Therefore, the

after-tax present value of the alternative is:

$10,000 – $10,000 x (1.18)-30 = $10,000 – ($10,000) x 0.006975 = $9,930.25

11.5

Choice Masters must choose between two projects of unequal lives. Project 1 has a NPV of

$50,000 and will be viable for five years. The discount rate for project 1 and project 2 is 10

percent. Project 2 will be viable for seven years. In order for Choice Master to be indifferent

between the two projects, what must the NPV of project 2 be?

Solution:

The EAC for project 1 is:

(1 + .0.1) 5

0.1*$50,000*

=$13,189.87

5

(

1

+

0.1

)

−1

which means that project 2 must also generate cash flow of $13,189.87 per year for seven

years. Therefore, the NPV of project 2 must be

1

1

$13,189.87*

−

=$64,213.83

0.1 1 (1 + 0.1) 7