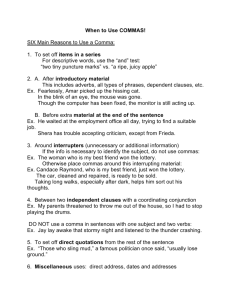

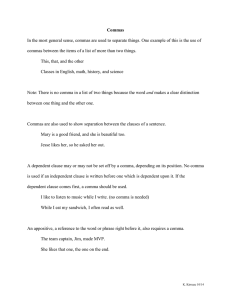

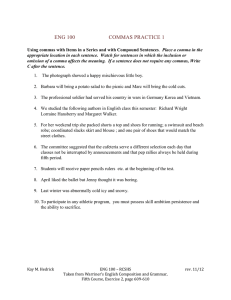

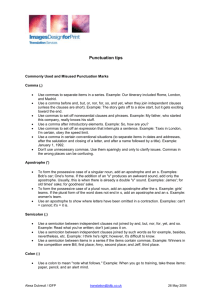

Sentence or fragment? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Louis Armstrong was one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. He was one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. Louis Armstrong, who was one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. Who was one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. Louis Armstrong, who was one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century, was a vocalist as well as a trumpet player. Today, he is considered one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. He is, however, considered one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. He is now considered one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. Because of his virtuosic trumpet skills, Louis Armstrong is considered one of the greatest jazz musicians of the twentieth century. Although he was one of the most virtuosic trumpet players of his generation. Prepositions James was angry ____ me. The main office is ____ Boston. The candy was divided ______ the members of the class. Rewrite as a single sentence. a) b) c) d) He did something in a hurry. He ran down to the cafeteria and got into the line. He did this as he had done daily. The line he got into was for fast food. a) b) c) d) e) f) g) This is about the soldiers. They retreated. They were shivering. This happenend two days ago. Their spirits were outraged. In addition, their spirits were crushed. This effect on their spirits was caused by the defeat. Simplifying sentences 1. When the clouds hung oppressively low, I had been passing alone and found myself, as the shades drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher. 2. I began to wonder what God thought about Wesley, who certainly hadn’t seen Jesus either, but who was now sitting proudly on the platform swinging his knickerbockered legs and grinning down at me. 3. That spirit of discord, which had jumbled my thoughts like powerful fingers sifting through sand or grains of rice, was gone. 4. The old woman pointed upwards interrogatively and, on my aunt’s nodding, proceeded to toil up the narrow staircase before us, her bowed head being scarcely above the level of the banister-rail. 5. The child, relinquished by the nurse, rushed across the room and rooted shyly in her mother’s dress. 6. He walked to the corner of the lot, then back again, studying the simple terrain as if deciding how best to effect an entry, frowning and scratching his head. Commas When in Doubt, Leave It Out! This is the single most important rule to keep in mind when dealing with commas on the ACT: if you aren't sure if you need a comma, you probably don't need a comma. In fact, you're far more likely to miss a question because you add in an unnecessary comma than you are to miss one because you left an important comma out. Take a look at the following ACT questions: Though it may be tempting to leave a comma after "value" or put one after "officials," the sentence is perfectly clear without either: Nevertheless, these tests convinced the officials of the value of using the Navajo language in a code. (H is thus the correct choice.) This principle holds for the next example as well: Write this sentence out with no commas and you get "Perhaps this legacy of letters explains what she meant when she said that her friends were her 'estate.'" Again, it makes sense without either comma, so D is the correct choice. Unfortunately as much as we may wish that we could just stop using commas altogether, there are certain times that they're necessary. The following four rules will help you determine when and where you need to place commas. An example of an extremely vital comma. 4 Key Rules for Comma Use The basic purpose of commas is to clarify relationships between phrases and clauses. That's a pretty broad goal, and there are a lot of different uses for commas. Luckily, you only really need to focus on a few main rules in order to do well on the ACT. The four rules you absolutely have to know deal with modifying phrases and clauses, introductory phrases and clauses, connecting independent clauses with a conjunction, and separating items in a list. Don't worry if that all sounds like gibberish: we'll go over each case with examples! Appositives, Relative Clauses, and Interjections As a general rule, any part of a sentence that can be removed without changing the sentence's fundamental meaning must be bracketed by commas. Take, for example, the following sentence: Timmy who loves Superman is excited for the upcoming movie. The point of the sentence is that Timmy is excited about the movie—his love of Superman is just helpful background info. Since taking out "who loves Superman" wouldn't affect the main idea of the sentence, that clause needs to be separated from the rest of the sentence by commas, like so: Timmy, who loves Superman, is excited for the upcoming movie. If you aren't sure whether a part of a sentence needs to be surrounded by commas, try crossing it out. If the sentence still makes sense, then the commas are needed; if it doesn't, then they aren't. Let's try it out with an example: The student who forgot her homework got detention. "Who forgot her homework" seems like it might need to be set off with commas, so let's cross it out and try reading the sentence again: The student who forgot her homework got detention. With that clause crossed out, it's no longer clear which student got detention, so by removing it we have changed the meaning of the sentence. This means that it shouldn't be surrounded by commas. With these general principles in mind, let's examine the three main cases, which—as you may have guessed from the title of this section—are relative clauses, appositive phrases, and general interjections. Relative Clauses: Non-Restrictive vs. Restrictive Relative clauses are dependent clauses that describe a noun and start with a relative pronoun or adverb like "which," "that," or "where." The rule for using commas with relative clauses is that you don't use commas around a clause if it's restrictive, i.e. it clarifies the specific thing you're talking about, but you do use commas if the clause is non-restrictive, i.e. it merely comments on a clearly defined noun. This may seem confusing, but it's much clearer in practice, so let's look at the two types of clauses individually. Restrictive: These are clauses that are necessary to the meaning of a sentence—they clarify exactly who or what you're talking about. You can't take a restrictive clause out of a sentence without fundamentally altering its meaning. Take a look at the example below. People who dislike kale won’t enjoy green smoothies. In this sentence, if you take out the clause “who dislike kale,” you’re left with “People won’t enjoy green smoothies,” which is not making the same point as the original sentence. Because this kind of clause can't be removed without changing the meaning of the sentence, it should not be marked off with commas. Non-Restrictive: These are clauses that provide additional information and are therefore not integral to the meaning of the sentence. My sister, who dislikes kale, doesn’t enjoy green smoothies. The point of this sentence is that my sister doesn’t enjoy green smoothies; even if you remove the underlined portion, that point is still made. Unlike in the example of a restrictive clause above, the underlined portion is not vital to meaning of the sentence. As such, it needs to be separated from the main thought of the sentence with commas. An important point for the ACT: clauses starting with "which" are always non-restrictive, while those starting with "that" are always restrictive. This means that "which" ALWAYS takes a comma and "that" NEVER does: I love reading books that are full of adventure because they take me away from my boring life. I love Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, which is full of adventure, because it takes me away from my boring life. Appositive Phrases Appositive phrases are basically the grammatical younger sibling of descriptive clauses: they serve the same purpose, describing a noun or pronoun, but they don't include a verb. Nonetheless, the basic rule for comma use is identical. If a phrase can be removed without changing the meaning of the sentence, it needs to be surrounded with commas. Consider the following examples. Where do you think they need commas? Her mother a doctor was often late. → Her mother, a doctor, was often late. Jonah a fifth-grader jumps rope on the playground everyday. jumps rope on the playground everyday. → Jonah, a fifth-grader, The nouns "a doctor" and "a fifth-grader" modify "her mother" and "Jonah," respectively, but they aren't necessary to main gist of the sentences. The one slightly confusing spin on this rule is that when the order of appositives are reversed, they usually don't require commas anymore. Ernest Hemingway, an author, wrote nine novels. Ernest Hemingway an author wrote nine novels. In the above example, we employ our strikethrough strategy and determine that the commas are appropriately placed. However, when we reverse the word order below, you'll notice a change. Author Ernest Hemingway wrote nine novels. Author Ernest Hemingway wrote nine novels. Even though "author" now comes first, it's still modifying "Ernest Hemingway." This means that "Ernest Hemingway" shouldn't be set off with commas; as you can see, the sentence wouldn't make sense with his name removed. Moreover, tempting as it may be to put a comma after "author," it's actually serving as an adjective in this context. Just like you wouldn't put comma in the middle of "President Barack Obama," you shouldn't stick one in "Author Ernest Hemingway." Interjections The last case we'll discuss is interjections, which are words or short phrases that disrupt the flow of a sentence like "of course." We tend to use these a lot more when we speak than when we write, but they do pop up on the ACT occasionally. What you are more likely to see is the related construction that occurs when a transition word is moved into a sentence, like in the following example. Version 1: However, my sister refused to help me move the couch. Version 2: My sister, however, refused to help me move the couch. The second type of sentence structure appears relatively frequently on the ACT—just know that if you see a transition word interrupting a clause, it needs to be set off with commas. We've covered a lot of information and it may seem really complicated, but the important thing is to remember the fundamental principle: if something is surrounded by commas, then it isn't important to the main point of the sentence. ACT Applications ACT questions about appositives and relative clauses usually require you to determine whether you need a comma to complete a pair and, if so, where it needs to go. Let's go through the question step by step. As written, this sentence doesn’t have a main verb—it’s just a subject, “Houdini,” followed by a long non-restrictive clause—so F can't be correct. J doesn’t solve this problem. G and H both place a comma after spiritualism, which gives you the non-restrictive clause “who devoted considerable effort to exposing hoaxes involving spiritualism.” If you cross that out, you’re left with either: G) Houdini, who devoted considerable effort to exposing hoaxes involving spiritualism, being skeptical about the existence of spiritualism. or H) Houdini, who devoted considerable effort to exposing hoaxes involving spiritualism, was skeptical about the existence of supernatural beings. H is clearly correct, since "being" isn't a correctly conjugated verb. (In fact, answers with "being" are almost always wrong: see our post on quick tips for the ACT English for a more in depth explanation and other helpful tips.) The key to this question is determining what belongs in the relative clause and then making sure that what's outside of that adds up to a complete sentence. Introductions Now that we've covered when to use commas to with phrases and clauses inside the main clause of a sentence, let's discuss when you need commas to separate clauses and phrases that come at the beginning of a sentence. The short answer? Always. The basic rule for using commas with introductions is that any time a sentence starts with a dependent clause or modifying phrase, it must be followed by a comma: Even though I was tired, Jenny convinced me to go to the strawberry festival. In the library, she found the books she needed. Weird-looking as it was, the lizard was sort of cute. In each of these examples, the underlined portion serves to introduce an independent clause. Weirdly, if you reverse the order of the sentence, you usually don't need the comma any more: Jenny convinced me to go to the strawberry festival even though I was tired. She found the books she needed in the library. The third example sentence is a slightly different case, since you can't actually put the underlined clause at the end of the sentence—it's a modifier and thus needs to be next to what it's describing, which in this case is the lizard. You can, however, move it into the sentence: The lizard weird-looking as it was was sort of cute. Any idea what this version of the sentence is missing? That's right: a comma on either side of "weird-looking as it was," which could be removed without fundamentally altering the meaning of the sentence. The correctly punctuated version looks like this: The lizard, weird-looking as it was, was sort of cute. ACT Applications The ACT rarely tests the introduction rule directly; instead, you'll usually see it come up in questions that have multiple phrases or clauses strung together. Take a look at the following example: "The next morning" is an introductory phrase, so it must be followed by a comma—this rules out answer D. Answer choice C has an improperly placed semi-colon, so we can eliminate it as well. (For more info on semicolon rules, check out our post on other punctuation!) Now we just have to decide whether the commas should surround "using twigs" or "using twigs for kindling." Let's try each version with our strikethrough strategy from the last section. A. The next morning, using twigs, for kindling she starts a small blaze B. The next morning, using twigs for kindling, she starts a small blaze Answer B is clearly the correct choice, since it correctly punctuates both "the next morning" and "using twigs for kindling." When dealing with commas, always remember that when you surround something with commas, you're telling the reader that it can be removed without altering the main point of the sentence. Connecting Independent Clauses (with a Conjunction) The other main case where you need commas to separate clauses is when you use a coordinating conjunction to connect independent clauses. If you have two independent clauses and want to combine them into one sentence, you can use a comma and a coordinating conjunction, or FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), instead of a semicolon. You probably use this construction correctly all the time without even thinking about it! I wanted to go hiking, but it was pouring rain all day. The important thing to remember is that using just a comma (no FANBOYS) to connect two independent clauses is absolutely always incorrect. A comma isn't interchangeable with a semicolon. This mistake is called a comma splice, and it's one of the most common errors students make on the ACT English. Incorrect: I had a terrible case of the flu, my mom brought me chicken noodle soup in bed. Correct: I had a terrible case of the flu, so my mom brought me chicken noodle soup in bed. Correct: I had a terrible case of the flu; my mom brought me chicken noodle soup in bed. ACT Applications On the ACT, this comma rule is usually tested in the context of other types of punctuation or in terms of identifying independent and dependent clauses. For more information on this, see our post on correctly connecting independent clauses. Lists The last comma rule is likely the one you're most familiar with: in lists of three or more items, you must place a comma after every item except the last. It's really as simple as that, as you can see in the examples below. The pirate loves going to Barbados because there's so much to do, including shopping for eye patches, sharpening his sword, and visiting the pub. Today, I'm going to skip school, go to the movies, and eat a giant bag of popcorn. Note that on the ACT you must use the oxford, or series, comma, which goes before the "and." Lists of Two Items The ACT writers won't give you a bunch of lists with no commas in them—instead they'll try to trick you in subtler ways. After looking at the last two rules, you might assume that you need to put a comma anywhere you see "and," but that's not the case! If "and" (or any other coordinating conjunction) is connecting two things that are not independent clauses, then you DON'T use a comma. James and his brother traveled to Oregon and Washington. The ACT writers' other favorite trick is to give you lists that don't look like lists because each item is so long. Yesterday, Talia went on a boring first date that she left early and plotted to take over the world using nothing but duct tape and string. You don't need commas in either of these cases because they are lists of only two items. Lists of Adjectives This is a slightly different type of list, but it does come up on the ACT occasionally. If you have more than one adjective in front of a noun or pronoun and their order doesn't matter, then you need to put a comma between them. Let's look at two examples, one where you need a comma and one where you don't: The hot dry desert The first female astronaut Which one do you think needs a comma? If you're not sure, check whether the examples make sense with the order of the adjectives reversed: The dry hot desert The female first astronaut The first example makes perfect sense with the new word order, so it does need a comma: the hot, dry desert. The second, however, doesn't work when the order of the adjectives is switched, so no comma is needed: the first female astronaut. ACT Applications As I mentioned above, ACT questions about lists tend to try to throw you off by adding in complicating factors like lots of extra words or commas being used for another purpose. Let's take a look at an example of this: It may seem like you need a comma after "labor," but this sentence is actually correct as written. It is a list of two things: "of her labor" and "of the fire's magic." A, no change, is the correct choice; the other answers only complicate the sentence. (This question also deals with parallelism, which you can learn more about here.) Remember the fundamental rule of commas: when in doubt, leave it out! When NOT to Use a Comma We just spent a long time going over when you do need commas, so let's circle back to that first principle by examining some places where you should NEVER put commas. Between a Subject and a Verb Commas exist to clarify the relationships between clauses and phrases, so it is NEVER correct to stick one in the middle of a single thought. Any sentence where there is a lone comma between a subject and its verb is incorrect: Incorrect: She, ate a lot of cookies. Correct: She ate a lot of cookies. In the above example, the comma is pretty clearly out of place, but that isn't always the case: Incorrect: Walking to the store, was a chore. Correct: Walking to the store was a chore. Once again, the comma is unnecessary and should be removed: "walking" is the subject and "was" is the verb. But it's much less obvious, since it seems like "walking to the store" is an introductory phrase, which would require a comma. Before or After a Preposition Another place you may think you need commas is at the beginning of prepositional phrases; after all, I just said that commas should only be used to seperate clauses and phrases. However, on the ACT, it is NEVER correct to place a comma after a preposition and very rarely correct to place one before a preposition. Let's look at some example of incorrect comma placement: Lucy enjoys reading aloud, from Harry Potter every night. Jim watched the terrifying horror movie, in the new theater on, 2nd Avenue. Though these commas may seem correct, they are unnecessary and just add clutter to the sentences. The correctly punctuated versions have no commas: Lucy enjoys reading aloud from Harry Potter every night. Jim watched the terrifying horror movie in the new theater on 2nd Avenue. The one, very rare, exception to this rule is when a preposition introduces a nonrestrictive clause. For example: Julie, for whom I was waiting, got to the restaurant very late. Because "for whom I was waiting" is actually non-restrictive clause, you do need the comma before "for." However, this only rarely comes up on the test—you are much more likely to make a mistake by putting a comma in front of a preposition than by leaving one out. Around an Emphatic Pronoun What on earth, you're wondering, is an emphatic pronoun? The emphatic pronouns are myself, yourself, herself, himself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, and themselves when they are used immediately after a noun or other other pronoun: I myself The book itself These constructions sound like they need commas, but emphatic pronouns should never be surrounded by commas. Incorrect: The pope, himself, will be at the party. Correct: The pope himself will be at the party. This may seem like a fairly obscure rule: it is! However, it shows up on the ACT fairly often, so it's worth studying anyways. Try Your New Knowledge Out! We've covered a lot of material and hopefully armed you with some helpful new strategies for tackling commas on the ACT English, but it's one thing to read about comma rules and another to put them in practice. With that in mind, I've created some practice ACT questions for you test out what you've learned. 1. The soft, blue cloth slid through her fingers easily. A. NO CHANGE B. blue, cloth slid through C. blue cloth slid, through D. blue cloth, slid through 2. After hearing good things about it, I wanted to read Crime and Punishment, but the book, itself, turned out to be super boring. A. NO CHANGE B. the book itself, C. the book itself D. itself 3. Talking to my friends, on the phone, is one of my favorite things to do. A. NO CHANGE B. friends on the phone C. friends on the phone, D. friends on, the phone 4. I wasn't planning on going to the wedding, however you've convinced me that it's a good idea. A. NO CHANGE B. wedding, however, C. wedding. However, D. wedding, Answers: 1. A, 2. C, 3. B, 4. C Essential and nonessential clauses. The girl who is standing beside the coach is our best swimmer. Janice, who is standing beside the coach, is our best swimmer. Punctuate as needed. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. I like movies that have happy endings. Jeff Brush whose sculpture was was selected by the judges has won a scholarship to art camp. This is the house where James Thurber lived as a child. The ships that dock here are foreign vessels. This photograph which I found in a trunk in the attic shows my great-grandmother as a girl. That was the summer when I met my best friend. Chris often discusses problems with her mother who is remarkably understanding. Sadie’s Aunt Carla whom I interviewed last week gave me some interesting information about the history of Sacramento. 9. The person who delivered the package was wearing a brown uniform and baseball cap. 10. The White House which is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is the home of the president and his family. English Journalist Couldnt Bear Abuse’s of the Apostrophe John Richards, who has died at age 97, founded a society to promote correct punctuation Retirees are often urged to find new activities and causes. After a career as a newspaper reporter and editor in England, John Richards took up the role of defending the apostrophe, an often abused punctuation mark. When he started the Apostrophe Protection Society in 2001, there were only two members, Mr. Richards and his son, Stephen. Soon, however, he had more than 250 members, and some made unsolicited cash donations. Letters and emails arrived from all over with examples of misuse of the apostrophe. Many offenders left the apostrophe out of possessive phrases or inserted the mark where it wasn’t needed, as in market signs advertising “apple’s.” Then the crusade ran into resistance. Mr. Richards told the Daily Mail that he spotted a restaurant advertising “coffee’s.” He offered free advice. “I said very politely, ‘It’s not needed. It’s a plural,’” Mr. Richards said. “But the man said: ‘I think it looks better with an apostrophe.’ And what can you say to that?” In 2019, he shut down his campaign. “The barbarians have won,” he said. “I’m just not as enthusiastic as I was,” Mr. Richards said. “I think it may be an age thing, but somehow the apostrophe doesn’t seem to matter to me as much as it did.” Mr. Richards died of sepsis on March 30. He was 97. John Belton Richards, the son of a postal worker and a shop employee, was born Sept. 17, 1923, in London. He spent his career working at newspapers in London and southeast England. After retiring from the West Sussex Gazette in 1988, he lived in Boston, England. ‘I think a lot of the change now is due to laziness and ignorance. It’s going downhill.’ — John Richards When he wasn’t campaigning, he painted with watercolors, drew pictures and participated in a local theatrical group. He is survived by two children and a grandson. In defending the apostrophe, he tried to avoid hectoring or insulting anyone. His typical letter of advice opened like this: “Dear Sir or Madam, Because there seems to be some doubt about the use of the apostrophe, we are taking the liberty of drawing your attention to an incorrect use.” He accepted the natural evolution of language. “Of course English is changing,” he told the Washington Post in 2009. “If the change is an improvement, yes, that’s fine. I think a lot of the change now is due to laziness and ignorance. It’s going downhill.” Grammar, he said, “is a valued part of our civilization.” He chose his battles, however, rather than taking on all abuses of grammar and usage. In a 2001 interview with the New York Times, he said: “The incorrect use of ‘fewer’ and ‘less’ is another thing that annoys me. If I carry on, I’ll get quite worked up.” The 3 Apostrophe Rules You Need to Know for the SAT/ACT Apostrophe Usage in a Nutshell We use apostrophes in the English language to show one of 2 things: 1. Contraction 2. Possession Contraction Most students are fairly comfortable using contractions because they appear frequently in casual speech. Contractions are compressions of two words, as in the following examples: couldn’t (contraction of could and not) won’t (contraction of will and not) I’d (contraction of I and would) there’s (contraction of there and is) it’s (contraction of it and is) Why do we use contractions? They can be useful for shortening and simplifying speech, although many high school English teachers encourage their students to avoid using contractions in academic writing. With contractions, apostrophes serve as a visual indicator of the “bridge” between the two words. We use apostrophes to show contraction and possession. Possession We also use apostrophes as a way of showing ownership or possession. Apostrophes serve as visual indicators of who or what is the “owner” and who or what is the “possession.” Here are a few examples of possession in action: Margot’s thesis project –> the owner is “Margot” and the possession is the “project” The children’s book section –> the owner is “children” and the possession is “book” The students’ questions –> the owners are “students” and the possession is “questions” The Jones’ yard –> the owners are “the Jones” and the possession is “yard” Notice how the possession always appears after the owner in these examples. It’s also possible to show ownership by using possessive pronouns like their, my, or her. We discuss possessive pronouns (and other kinds of pronouns!) in our comprehensive Guide to Pronouns on the ACT and SAT post. Apostrophes and the SAT/ACT Students will encounter apostrophe questions on these 2 sections: ACT English SAT Writing & Language As we’ve mentioned in our other grammar posts, however, knowledge of apostrophe rules can be helpful elsewhere, such as the optional essay section on both tests. Essay graders will be checking for effective use of English conventions in your response, so proper grammar can help you achieve a higher essay score. Apostrophe questions appear relatively infrequently on both tests, although they are still worth preparing for. Here’s a breakdown of what you can expect to see on either test: Apostrophe Questions on the ACT Apostrophe Questions on the SAT 1-2 0-2 *Based on analysis of officially released ACT and SAT practice tests When you do see an apostrophe question on ACT English or SAT Writing & Language, you’ll largely have to worry about possession rules. Your knowledge of contraction is only tested in one very specific way, which we discuss in the next section. How can you tell that you’re dealing with an apostrophe question? You will likely see contractions and/or apostrophes in the answer choices! The 3 Apostrophe Rules You Need to Know Now it’s time to take a deep dive into the 3 apostrophe rules you’ll need to know for ACT English and SAT Writing & Language. Rule #1: Its vs. It’s This may sound like an obvious rule to some students, but both the SAT and ACT are very likely to test your knowledge of the difference between “its” and “it’s.” The difference is that “its” is the possessive form of the pronoun “it,” while “it’s” is a contraction that really means “it is.” its it’s the possessive form of “it” the contraction of “it is” The dog wagged its tail. I think it’s going to rain today. If you see its, it’s, and/or both of these in your answer choices, read carefully! We recommend reading “it’s” as “it is” to help with your elimination process on these types of questions. Rule #2: Add ‘s to singular nouns showing ownership To show ownership with a singular noun, simply add an ‘s to the end of that noun. This is likely to be the easiest possession rule for students to remember. Check out these examples of singular noun possession: Dmitri’s dreams The cat’s favorite window sill The Earth’s curvature My mother’s phone calls The podcast’s listeners How can you tell if a noun is singular? There should be only one of that particular noun. For example, there is only one Dmitri, one cat, one Earth, etc., in the sample phrases above. Rule #3: Add a single apostrophe to the end of plural nouns ending in “s” If you’re showing ownership with a plural noun that ends in “s,” all you need to do is add an apostrophe to the end of that noun. Here are some examples of plural noun possession: The books’ covers The sidewalks’ cracks My teachers’ curriculum The mountains’ peaks The computers’ hardware Besides the fact that these plural nouns end in “s,” you can tell that they are plural because there is more than one of each. From the examples, we know that we are discussing more than one book, sidewalk, teacher, mountain, and computer. Not every plural noun ends in “s,” however, and it’s possible to have a singular noun that ends in “s.” We discuss what to do in these scenarios below. Singular Nouns Ending in “S” What about singular nouns that end in “s,” including proper nouns like Chris? You still follow the rule of adding an ‘s to these nouns. Here’s what that would look like: Chris’s classes The iris’s stamens The sea bass’s flavor James’s preferences Nicholas’s parents We know it feels awkward, but that’s the rule! The only exception to this is with proper nouns that have historical and/or biblical associations, like “Moses” or “Jesus.” In these instances, all you need to do is add an apostrophe to the end: Moses’ leadership Jesus’ teachings However, don’t worry about this exception–it won’t be tested on the ACT or the SAT. Plural Nouns That Don’t End in “S” Yes, you can have a plural noun that doesn’t end in “s”! What happens if you want to show possession with one of these nouns? All you need to do is treat it like a singular noun: add an ‘s to the end. Check out these examples: The children’s games People’s voting habits Women’s rights Sheep’s wool The phenomena’s relevance In the next section, we’ll discuss how to apply these 3 apostrophe rules to SAT Writing & Language and ACT English punctuation questions. Apostrophe Rules: Our 4-Step Strategy for Applying Them When you encounter an apostrophes question on ACT English or SAT Writing & Language, follow these strategic steps: 1. Read the full context 2. Identify if you’re dealing with a case of contraction or possession 3. If possession, identify who/what is owning who/what & apply apostrophe rules 4. If contraction, eliminate rule-breakers and plug in your final choice We’ll apply these steps to 2 sample apostrophe questions from an ACT and SAT official practice test. Example 1: ACT Apostrophe Question Source: ACT Official Practice Test #1 1. Read the full context The apostrophes in the answer choices indicate that we will most likely have to apply our knowledge of apostrophe rules to this question. The full context tells us more about Jones, an individual who became a strong advocate of a particular movement. 2. Identify if you’re dealing with a case of contraction or possession This may seem tricky, but close analysis of the answer choices and underlined portion indicate that we’re dealing with possession. Three of the answer choices contain the possessive noun movement’s and two contain possessive forms of the noun advocates. 3. If possession, identify who/what is owning who/what & apply apostrophe rules Context tells us that movement is the “owner” of advocates. Movement is a singular noun, so we will need to add an ‘s to the end to show proper possession: movement’s. We can now eliminate answer choice J. Some of our answer choices have apostrophes associated with the plural noun advocates, but advocates in this context does not “own” anything. We can eliminate answers F and G and choose answer H. Here’s how the corrected sentence would look: Jones, however, became one of the movement’s most powerful and controversial advocates. Example 2: SAT Apostrophe Question Source: CollegeBoard SAT Official Practice Test #1 1. Read the full context The answer choices indicate that we might have to apply our knowledge of apostrophe rules, as two of the answers include apostrophes. The word “major” also appears in different forms, so we might have to apply additional grammar rules (a common case on both ACT English and SAT Writing & Language). Context tells us that this sentence describes philosophy majors and their professional pursuits. 2. Identify if you’re dealing with a case of contraction or possession This is a bit of a trick question, as close analysis of the sentence in question tells us that we are dealing with neither contraction nor possession! That’s because students is simply a plural noun and does not “own” anything. The phrase majoring in philosophy is describing these particular students. We can immediately cross off answers A and D, as these both have apostrophes in them. The appropriate form of major is majoring, as majoring in philosophy is describing the students. Our correct answer is B. Some of you might be thinking, Hold up–why is this an apostrophes question? It’s an apostrophes question because it does require knowledge of apostrophe usage, even if we didn’t end up choosing an answer choice with an apostrophe! In fact, this is very typical of ACT English and SAT Writing & Language questions. Semicolon, Colon, and Dash 1. The Semicolon [ ; ] A semicolon serves as a period between two closely related sentences. For proper usage of a semicolon, there must exist: A complete sentence before the semicolon. A complete sentence after the semicolon. If either of these rules is broken, then the semicolon is not being properly used. Proper Usage I like tennis; you like golf. The SAT is a long test; it bores me. I am training for a marathon; I’m almost ready. Improper Usage Although I like tennis; you like golf. (incomplete sentence before the semicolon) The SAT is a long test; which is very boring. (incomplete sentence after the semicolon) I am training for a marathon; It will take place soon. (do not capitalize the word after the semicolon) 2. The Colon [ : ] Most high school students rarely, if ever, use colons in their writing. Colons are used in a very specific way, which we’ll cover below. Note: colons and semicolons cannot be used interchangeably. The SAT Writing section tests 2 main colon rules: A colon comes before a list A colon comes before an explanation Proper usage of colon before a list: At my job I do the following things: answer the phone, schedule appointments, and organize files. I like tropical fruits: mango, guava, and passionfruit. There’s only one food I can’t resist: bacon. (list of one) Improper usage of a colon before a list: At my job, I: answer the phone, schedule appointments, and organize files. I like tropical fruits such as: mango, guava, and passionfruit. I want to eat: mango, guava, and passionfruit. In all of the list examples above, no colons are necessary to introduce the list. Proper usage of a colon before an explanation The new secretary was a poor fit for the job: she couldn’t stay awake at work. If I don’t exercise every single day, I won’t exercise at all: I’m a creature of habit. This chef is like a magician: he can turn the simplest ingredients into complex culinary creations. What comes after the colon can explain, clarify, or illustrate the idea before the colon. In these scenarios, the idea before the colon is often a full sentence. 3. The Dash [ – ] The dash is extremely versatile. Students often use dashes informally in writing, but the SAT tests students’ formal understanding of proper dash usage. The SAT Writing section often tests the following rules: Dashes surround non-essential phrases/clauses Dashes before emphasis, explanation or list (much like a colon) Proper usage of a dash to surround a non-essential phrase/clause: The man — a scary looking fellow with bloodshot eyes — smiled and waved. The packages arrived — nearly 3 weeks after the estimated delivery date — and we no longer had any use for their contents. Note that pairs of commas or parentheses can often be substituted for dash pairs. Proper usage of a dash before emphasis or explanation, or a list: The little girl finally got what she wanted — a puppy. This year I would like to accomplish some important goals — getting healthy, reading more books, and spending more time with family. I realized that she was going to be the best athlete I had ever trained — her work ethic was unmatched. In the above examples, a colon could be substituted for the dash. Subject-Verb Agreement 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. The class ___ to enter their pictures in the contest. The author and illustrator ___ Kim Long. Meteorologists ___ weather patterns. The Wind in the Willows ___ my brother’s favorite book. Mathematics ___ difficult for me. Those blue jays or that cardinal ___ the old bread. In the alley behind the building ___ three dumpsters. A brook ____ through the leafy forest. Everyone ___ an interest in the tournament. The children ___ watching the cartoon. James ___ happy at his new school. The farms of Nebraska ___ millions of bushels of grain. Across the ocean ___ millions of immigrants. The fangs of a rattlesnake ___ poison to its prey. A nest of hornets ___ in the barn. New York, Denver, and London ___ smog. The captain and leader of our team ___ Miss Fonda. Neither family responsibilities nor illness ___ kept Mrs. Portero from her job as a mail carrier.