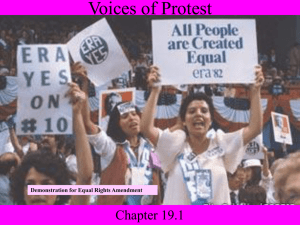

1 Running Head: THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE The Equal Rights Amendment & Social Change Your Name Here Southern New Hampshire University 2 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE The Women's Suffrage Movement ushered in a new era of progressive ideas and social reforms. With time and hard work, suffragists secured the right to vote with the 19th Amendment in 1920. As a result, a critical piece of legislation known as The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA); initially named the Lucretia Mott Amendment, was introduced in Congress. The Amendment sought to expand equality between the sexes. Ultimately the U.S. failed to ratify the ERA due to a divide between traditional and modern feminist ideologies. Feminists argued against each other on what the ERA would mean for American culture and social progress. Since the ERA's introduction to Congress, there have been many changes to American society. Progress for true equality between Americans has continued slowly and painfully. In time various groups like the LGBT community sought and gained equality and protection on several vital issues. Given the social transformations since 1920, public opinion has changed, and arguments have evolved on what equality means for American life. Given the societal progress made over the years, we must question the arguments of those supporting and against the ERA and how it fits in the evolving society of today. Constitutionally we continue to lack true equality between all citizens as a fundamental right. Given the history of our nation, it has been by design to equalize civil liberties and make all citizens equal under the law. We must hold steadfast to the ideals set forth by the founders. Citizens and legislators alike must effort to create a more perfect union and reintroduce an updated version of the ERA into Congress. Congress approved the ERA in 1943 and shifted the challenge for its supporters to securing three-fourths of the State's, in hopes of ratification. With the revised and submitted ERA, the passage appeared necessary and righteous, yet a divide between feminists would prove the task challenging. Sam Ervin, a Senator from North Carolina, complained to the Senate that 3 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE there was no time limit on the ERA's ratification (Kyvig, 1996). Without any opposition, a rider was attached to the ERA, designating a time limit on the proposed Amendment. Unbeknownst to congressional sponsors and civilian supporters, the time limit would prove arduous. A time limit on proposed amendments is not necessary, and Senator Ervin's complaint was merely a political tactic, "which was overlooked," and aligns with, "[a] lengthy list of objections on whatever grounds he could find" (Kyvig, 1996, p.56). The imposed time limit is now seen as a contributory cause in the long line of challenges, leading to the ERA's failure. Other challenges laid ahead in ratifying the ERA. A significant portion of feminists believed that women and children, "for whom they were principally responsible [for] faced economic, social, and marital exploitation," if the ERA were to pass (Kyvig, 1996, p.49). While feminists were able to unite over the single cause in securing the right to vote, they were ideologically divided due to ideas about what the ERA would mean for their roles as a wife, mother and their children. Beyond the individual beliefs disuniting the two factions of feminists, several large organizations opposed the ERA. One of the most influential and vocal was the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. One of their arguments was that if the ERA were successful, "women's proper roles as mothers, wives, and moral beacons would be sullied through participation in politics" (Kyvig, 1996, p.48). In current American culture, families and functions are different than the traditional gender roles applied in the 1920s. Mothers and fathers tend to work, dividing their time equally toward child-rearing, and supporting the household financially. It would be amiss to believe that the predilections of a previous generation reign supreme in overall American society currently. The de facto social climate doesn't and hasn't aligned with the de jure reality in many decades. 4 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE While organizations and traditional feminists yielded a siege against what would now be considered a "common sense" amendment; anti-ERA supporters like Phyllis Schlafly fueled the discussion by instilling fear among the people. Schlafly fought zealously against the ERA; testifying in Congress and speaking her opinion publicly on the ERA and what it would do to American families and society. Here is an excerpt of Schlafly's testimony in Congress in 1983, "the word used in ERA is "sex," not "women," and the "sex" in the ERA is not defined or limited in any way. One would have to be blind, deaf and dumb not to be aware of the political activism of the homosexual community and their attempts (usually unsuccessful) to legislate their "gay rights" agenda at the Congressional, state legislative, and city council levels" (Testimony of Phyllis Schlafly, 1983). It's clear that in Schlafly's testimony is that of a relic when compared to modern social views. Had Schlafly repeated the same words today, she would be damned by the majority of the American population. While her rhetoric was socially acceptable in that era, it is most definitely not a reflection of American society today. Her testimony is just one example of the fearmongering, self-righteous political agenda used by Schlafly to divide and slay meaningful legislation. While Schlafly and others organized against the ERA, Mary Frances Berry testified before Congress on the realities of inequality in the United States. Berry's testimony connected gender inequality to various aspects of American life, "We also documented sex discrimination in a lot of other areas including marital property, domestic relations law, social security, disability, pensions, the administration of justice and the military . . . we believe that one reason sex discrimination persists is that we lack a firm constitutional basis for equal rights on the basis of gender" (Testimony of Mary Berry, 1972). 5 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE Berry also understood the historical perspective relative to the passing of constitutional amendments stating this, "We are not dissuaded because it is taking a lot of time to get ERA passed. If you look at the history, constitutional amendments, most of them, if they are substantive, take years to get passed. It does not bother me" (Testimony of Mary Berry, 1972). However, Senator Ervin's insertion of the time limit for ERA ratification would later prove the challenge much more difficult. The ERA had supporters, as well as opossers, but the voice of fear, along with political restraints, hindered progress at the national level. The lobbying of organizations against the ERA, by the likes of Phyllis Schlafly, damaged the de facto social frameworks for the LGBT community. In the time since the failure of the ERA, the LGBT community persevered and secured the right to get legally married; a result of a landmark ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015. Paving the way for legislation protecting members of the LGBT community from hate crimes based on sexual identity and expression, and are now punishable under federal law. The reach extends to discrimination based on sexual orientation and discrimination when it comes to housing and employment as well. Had the ERA been introduced without time limits, and the opposition leaders like Phyliss Schlafly been unable to speak their public distaste on current social norms; the ERA would have succeeded, and equality would be distributed more equitably to all groups of citizens in this country. While obtuse tactics are not new to American politics, the reality is the actions of a few, impact the lives many. Had the ERA passed Congress without time limits attached, the probability for success in today's political and social environment would be near-absolute. American citizens and especially young adults are more accepting of equality and tolerant of diversity in all walks of life than ever before in American history. 6 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE When we consider the social dynamic of families in current culture, versus that of the early, to mid-1900s, there are only remnants of the societal trends of the last generations. When we consider families with children, in over 63% of the families, both parents work (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). If we review that statistics from 1967, only 43% of families had dual income (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). The change between now and then is 20%, which is a significant increase. When we consider the traditional views of women being primarily homemakers, the statistics no longer align with the social status. When we consider workforce participation, we must consider home life dynamics. While both earn income, both are absent from the home. Family home time and duties are more equally distributed. We are erasing the previous generations dated ideas and stereotypes on male/female gender roles in the home. This is an important topic to dissect when we start considering how society aligns with government policies, relative to divorce. There is little to no equality between men and women when it comes to divorce. According to the 2013 Census, updated January of 2016, only 17.5% of fathers had custody of their children (Grall, 2016). The disproportion findings overwhelmingly indicate a prejudice between men and women within the family court system. Only a handful of states have legislation protecting both parents equally when it comes to children and property. Overwhelmingly courts side with mothers for sole custody, leaving fathers only four days a month, on average to see their children. When we consider inequality, the ERA, and the social trends and dynamics over the last century; we must recognize the slow and painful timeline that reflects the various aspects of gender equality. With no federal protection between men and women, states can legislate and divide property and custody rights however they choose, without having to answer to the U.S. Supreme Court. The ERA failing added a multitude 7 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE of complexities to Americans in the process or having gone through a divorce. The complications and entanglements run wide and deep in the country when we examine gender equality on a micro and macro scale. One example relevant to recent events, if we consider the recent mass shootings that have grown in number over the last two decades; we see direct connection statistical findings related to fatherless homes. Author Warren Farrell in a recent interview and piece written by the Washington Times said this about children of divorce where fathers are absent, "[These Children are] much more likely to drink, much more likely to do drugs, much more likely to be depressed, much more likely to be suicidal, much more likely to be violent, much more likely to be in prison, and they're also much more likely to commit mass shootings" (Richardson, 2018). This further indicates how the inequality between men and women cause considerable damage to not only adults but children as well. Looking though history, we can draw a line connecting crime rates, poverty, suicide, and other severe issues in this country to nationwide statistics on divorce and parenting inequalities. Historians and future historians can continue research through many avenues. Census data and statistics will continue to validate the impact of inequality in the United States. Inequality between genders has had a severe impact in several critical perspectives of American life. We must ask how we let the fearful ideologies expressed by those like Phyllis Schlafly influenced a generation of Americans to continue a history of inequality. When will equality at the federal level be addressed in a meaningful way? If there is one thing we can learn from history, it is not only the observance and analysis of past events that shape the future, but the ambition of progressive thinkers, activists, and those refusing to settle for anything less than what is philosophically sound, to transform society, government, and law. 8 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT & SOCIAL CHANGE References Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Employment Characteristics of Families, Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf Congress, House, Committee on the Judiciary, Equal Rights Amendment: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 98th Cong., 1st sess. on H.J. Res. 1, July 13, September 14, October 20, 26, and November 3, 1983, Statement of Mary Frances Berry, Commissioner, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Congress, House, Committee on the Judiciary, Equal Rights Amendment: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 98th Cong., 1st sess. on H.J. Res. 1, July 13, September 14, October 20, 26, and November 3, 1983, Statement of Phyllis Schlafly Grall, T. S. (2016). Custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. Kyvig, D. (1996). Historical Misunderstandings and the Defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment. The Public Historian, 18(1), 45-63. doi:10.2307/3377881 Richardson, B. (2018, March 27). Link between mass shooters, absent fathers ignored by antigun activists. Retrieved from https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/mar/27/mass-shooters-absent-fathers-linkignored-anti-gun/