Melville's Symbolism: Water, Fire, Stone in Moby-Dick & Pierre

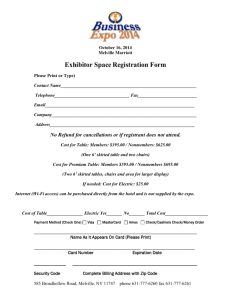

advertisement