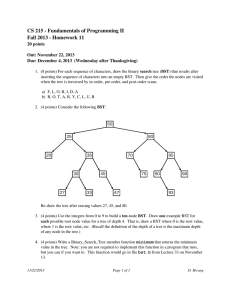

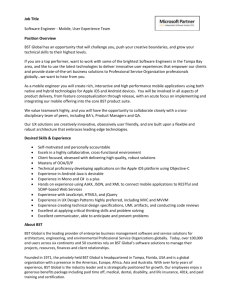

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS 2017, 50, 805–818 NUMBER 4 (FALL) PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BEHAVIORAL SKILLS TRAINING OF SOCIAL SKILLS REBECCA K. DOGAN OT&P MEDICAL PRACTICE MELISSA L. KING SOUTHEAST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY, AUTISM CENTER FOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT ANTHONY T. FISCHETTI BASIX BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CANDICE M. LAKE WEDGWOOD CHRISTIAN SERVICES THERESE L. MATHEWS MUNROE-MEYER INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA MEDICAL CENTER AND WILLIAM J. WARZAK MUNROE-MEYER INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA MEDICAL CENTER Impairment in social skills is a primary feature of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs). Research indicates that social skills are intimately tied to social development and negative social consequences can persist if specific social behaviors are not acquired. The present study evaluated the effects of behavioral skills training (BST) on teaching four parents of children with ASDs to be social skills trainers. A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design across parent–child dyads was employed and direct observation was used to assess parent and child behaviors Results demonstrated substantial improvement in social skills teaching for all participants for trained and untrained skills. Ancillary measures of child performance indicated improvement in skills as well. High levels of correct teaching responses were maintained at a 1 month follow-up. This study extends current literature on BST while also providing a helpful, low-effort strategy to modify how parents can work with their children to improve their social skills. Key words: autism spectrum disorders, parent training, behavioral skills training, social skills This study is based on a dissertation submitted by the first author in partial fulfillment of the Ph.D. degree at the University of Nebraska Medical Center – MunroeMeyer Institute. The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the support of the dissertation committee including Drs. Keith Allan and Blake Lancaster. Request for materials or reprints should be sent to Rebecca K. Dogan at rebecca.dogan112@gmail.com doi: 10.1002/jaba.411 Acquisition of social skills is frequently a difficult and prolonged process for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which extends far beyond formal social skills programming. Similar to other forms of behavior change, maintenance of social skills requires regular practice in a variety of settings, under varying circumstances, and with multiple people (Stokes & Baer, 1977). If training of novel skills is limited to one setting or individual © 2017 Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 805 806 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. (e.g., in a university environment with an experimenter), newly learned skills may not contact naturally maintaining reinforcers, which could adversely affect maintenance and generalization. Identifying a treatment package in which parents serve as the primary trainers is likely to increase the probability that treatment gains would generalize and maintain because parents have more opportunities to facilitate acquisition, and frequently accompany their children to novel settings (Matson, Mahan, & Matson, 2009). In addition, teaching parents to serve as primary trainers may benefit children, parents, and practitioners by saving time and resources. Extensive research has demonstrated the effectiveness of behavioral skills training (BST; i.e., instructions, modeling, role-play, feedback; Crane, 1995) to teach parents a range of skills (e.g., Crane, 1995; Crockett & Hird, 2009; Forehand et al., 1979; Gross, Miltenberger, Knudson, Bosch, & Brower Breitwieser, 2007; Hsieh, Wilder, & Abellon, 2011; Lafasakis & Sturmey, 2007; Magen & Rose, 1994; Miles & Wilder, 2009; Stewart, Carr, & LeBlanc, 2007). BST has been used to teach novel skills in very brief periods of time (e.g., Himle, Miltenberger, Flessner, & Gatheridge, 2004; Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010; Toelken & Miltenberger, 2012) and is viewed as an integral part of a number of well-researched and empirically supported parent training programs (e.g., McMahon & Forehand, 2003; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). Stewart, Carr, & LeBlanc (2007) were the first researchers to gather parent and child data to examine the effects of caregiver-implemented BST on social skill acquisition of a child with ASD. Targeted social skills included increasing eye contact, soliciting input from a conversational partner, and decreasing perseverative topics. All components of BST were incorporated into both training procedures (i.e., instructors training caregivers and caregivers training their child) and required thirteen 1-hr sessions to complete. Systematic replications and extensions of this research are necessary to support the use of parent-implemented BST to teach social skills to children with ASD. In doing so, limitations of Stewart et al. (2007) can be addressed. For instance, Stewart et al. used an A-B design, which does not control for threats to internal validity. The study also included a single child participant. Replication across additional individuals is needed to identify potential individual differences that could affect BST implementation. Furthermore, direct observation data were not provided on individual caregiver skills (i.e., parent and sibling data were combined; rehearsal and feedback skills were combined). The present study sought to replicate and extend Stewart et al. (2007). Experimental control was strengthened and replication was made feasible by using a multiple baseline design and precisely defining specific skills and responses for parent and child participants. The primary purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effects of BST as a teaching tool to train four parents of children with ASD to be social skills trainers. We evaluated both parents’ use of BST to teach social skills to their children. Finally, we examined whether training produced parent performance that maintained and generalized to contexts in which parents taught untrained and novel skills to their children. METHOD Participants Four parent–child dyads participated. All children had an IQ of 70 or greater and diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified. In addition, the children participated in at least one general education class and received a score of 70% or above on a pretreatment compliance check. As part of the compliance check, children were provided 10 simple, one-step instructions (e.g., “Hand me a tissue please”) and rates of compliance were PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST measured. The pretreatment assessment included interviews, direct observation, and formal assessments to determine if the child met criteria to participate. Some children had participated in applied behavior analysis (ABA) therapy, but none of their parents had formal hands-on training with ABA, social skills training, or implementation of BST. All parents were the biological mothers of their child and were between the ages of 37 to 47. Three parents reported their relationship status as “married,” and one reported being “separated.” All parents reported having other children living in the home. Parents were asked to complete two rating scales: the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist–Parent Report Form (CBCL–PRF; Achenbach; 1991) and the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; Gresham & Elliot, 2008). The CBCL–PRF was selected because it is applicable for children aged 6 to 18 years and includes questions that assess common childhood behavior problems, as well as subscales associated with ASD symptoms. The SSIS assesses social skill impairments in children aged 8 to 18 years. The assessed skills are in the areas of communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, engagement, and self-control. Problem behaviors (externalizing, bullying, hyperactivity/inattention, and internalizing) are also assessed. Both the CBCL–PRF and SSIS have favorable validity and reliability scores (Crosby, 2011; Nakamura, Ebesutani, Bernstein, & Chorpita, 2009). Dyad 1 (Hana and Carter). Hana and her son Carter (age 9) were African American. Hana reported having a master’s degree, an occupation as a nurse, and a family income of $50,000-$75,000 per year. She also noted a previous history of depression, but indicated she had received treatment. Based on the CBCL–PRF and SSIS parent-completed form, Carter scored in the above-average range on several of the problem behavior subscales and in the below-average range on the Social Skills 807 Standard Score subscales (see Supporting Information for all subscale and standard scores). Carter was verified and received services by school staff under the category of autism. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, 2000) was administered by the experimenter, a doctoral intern certified in administering and interpreting the ADOS, to verify that Carter met the qualifications for participation in the study. Carter was administered Module 3, which is designed for children and adolescents with fluent speech. Data suggested that Carter met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder, with his total score falling above the cut-off for that category. Dyad 2 (Shari and James). Shari and her son James (age 10) were Caucasian. Shari reported having a master’s degree, working for a nonprofit company, and having a family income of $50,000-$75,000 per year. Based on the CBCL–PRF and SSIS parent-completed form, James scored in the above-average range on multiple problem behavior subscales and in the below-average range on the Social Skills Standard Score. James also had a comorbid diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and was verified and received for services by a school psychologist under the classification of autism. Assessments provided by school staff included the ADOS, direct observation, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale, and the Behavior Assessment Scale for Children–II. Results from the autism assessment suggested that James met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder. Dyad 3 (Abby and Eric). Abby and her son Eric (age 9) were Caucasian. Abby reported having a bachelor’s degree, an occupation as a web designer, and a family income of $50,000$75,000 per year. Based on the CBCL–PRF and SSIS parent-completed form, Eric scored in the above-average range on several of the problem behavior subscales and in the 808 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. below-average range on the Social Skills Standard Score. Eric was verified and received for services by school staff under the category of autism. The ADOS Module 3 was administered by the experimenter. Data suggested that Eric met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder, with his total score falling above the cut-off for that category. Dyad 4 (Kathy and Sam). Kathy and her son Sam (age 12) were Caucasian. Kathy reported having a doctoral degree, an occupation as a professor at a local university, and a family income of $75,000-$100,000 per year. She also noted a previous history of anorexia but indicated she had received treatment. Based on the CBCL–PRF and SSIS parent-completed form, Sam scored in the above-average range on several problem behaviors. The Social Skills Standard Score could not be determined due to incomplete items. Sam received a diagnosis of PDD–NOS from a developmental pediatrician at the age of 5 years and was also verified and received for services by his school under the category of autism. The ADOS Module 3 was administered by the experimenter to verify whether Sam met the inclusion criteria for participation in the study. The assessment results suggested that Sam met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder. Kathy also reported that Sam was prescribed psychotropic medications; however, these medications remained unchanged throughout the duration of the study (see Supporting Information for full parent/child data). Setting and Materials All training took place at the residences of each parent–child dyad in a room that included a table and chairs for all participants and training staff. A SlideHD Flip video camera with tripod was used to record each session. The BST handout (see Supplemental Information) was provided to each parent during all phases following baseline. The BST handout was adapted from the steps listed in Working with Parents of Noncompliant Children (Shriver & Allen, 2008) and modified based on ratings provided by behavior analysts working in the field. Several professionals with experience conducting research using BST rated the steps associated with the BST method using a fivepoint Likert-type scale. Based on their ratings, the steps rated as most important were added to the BST handout. A puppet was also used in some sessions as a pretend conversational partner. Dependent Measures and Data Collection Primary dependent measure. The primary dependent measure was percentage of BST steps correct. During each trial, the parent had the opportunity to emit 15 correct teaching steps. We required correct performance for 5 of 15 steps: a) provide appropriate rationale and b) state all steps during the instruction component, c) provide an opportunity for skill demonstration by the trainer during the modeling component, d) provide an opportunity for skill demonstration by child during the role-play component, and e) provide immediate feedback. These steps were selected based on ratings provided by several professionals in the field with experience conducting research using BST. Professionals were asked to rate the steps associated with the BST method using a fivepoint Likert-type scale (i.e., 1 = most important; 5 = least important). The steps rated as most important by professionals with extensive experience in BST research were identified as required steps. Observers scored correct and incorrect steps using a direct observation data form. We calculated percentage of BST steps correct overall by dividing the number of steps correct by the total number of possible steps (15) and multiplying by 100. We calculated percentage of required BST steps correct by dividing the number of required steps correct PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST by the total number of required steps (5) and multiplying by 100. Secondary dependent measures 1. Child percentage of correct steps. Observers scored the number of correct social skills steps that the children performed during each trial. Social skills included joining in a conversation and asking for help (see Supporting Information for the steps required for each social skill). Percentage of correct steps was calculated by dividing the number of correct steps performed by the total number of possible steps comprising the skill and multiplying by 100. 2. Modified version of the Treatment Evaluation Inventory-Short Form. The Treatment Evaluation Inventory–Short Form (TEI– SF; Kelley, Heffer, Gresham, & Elliot, 1989) is considered a psychometrically sound, abridged version of the Treatment Evaluation Form (TEF), which was developed by Kazdin (1980) to measure the acceptability of behavioral interventions for children. Parent participants rated treatment acceptability on a variety of dimensions (e.g., acceptability, effectiveness, meaningfulness, willingness to continue use of treatment) on a five-point Likerttype scale (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The original form was modified in that the word “treatment” was replaced with “Behavioral Skills Training” and the questions were simplified to make them shorter. Interobserver Agreement (IOA) and Procedural Integrity Interobserver agreement (IOA) was assessed by having a second observer independently score at least 33% trials, across all conditions (i.e., baseline, training/supplemental training, posttraining, follow-up, and generalization 809 probe phases). Observations were randomly selected for each parent–child dyad for all conditions. IOA was calculated using the point-bypoint formula (i.e., number of agreements divided by the total number of agreements and disagreements, converted to a percentage). For the parents, the mean overall agreement scores were 100% for Hana, 98% for Shari (range, 95%–100%), 100% for Abby, and 98% for Kathy (range, 90%–100%). For the child participants, mean IOA values were 100% for Carter, 81% for James (range, 75% –100%), 100% for Eric, and 90% for Sam (range, 75% to 100%). Procedural integrity data for parentimplemented BST were collected during all training sessions for each parent. The following categories were evaluated: (a) presentation of the BST Parent Handout, (b) inclusion of correct components of BST during training, and (c) delivery of feedback following role-play. Procedural integrity was calculated by dividing the number of steps correctly presented by the total number of steps, multiplied by 100. Procedural integrity values were 100% for all parents. Experimental Design A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design (Watson & Workman, 1981) across parent– child dyads was used to evaluate the effects of BST to teach parents to implement social skills instruction with their children with autism. Procedure Session durations ranged from approximately 20–120 min. The maintenance probe, subsequent training, and follow-up sessions lasted 20–45 min, whereas the initial training session, consisting of three trials, required a total session duration of 120 min. Multiple trials were conducted in each session, but the exact number of trials varied depending on the phase and on the rate of parent skill acquisition (i.e., with a 810 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. minimum of two and a maximum of seven trials per session). A trial consisted of an opportunity in which a parent was asked to teach the graduate student playing the role of the child (in baseline) or their actual child a specific social skill. All trials lasted up to 10 min. The number of trials per participant varied during baseline due to the multiple baseline design, and the number of parent–child training and posttraining trials varied if the self-monitoring procedure (described below) was required. Throughout all phases of the study, vignettes were presented to provide contrived practice opportunities. The written vignettes included a brief description of a typical social interaction, the rationale for the skill, and the name of the skill being targeted. Vignettes were selected from The SCORE Skills: Social Skills for Cooperative Groups manual (Vernon, Schumaker, & Deshler, 1996) and adapted to fit the skills assessed in the current study (i.e., Joining in a Conversation; Asking for Help). Examples of the vignettes adapted for the joining in a conversation and asking for help skills are provided below: It is break time and you see your friends trying to come up with an idea of what to play. You are interested in playing ______ (activity) but need more people to play with you. Use the Joining in a Conversation Skill. You’re working on a class art project and are having trouble understanding the directions. You see your friend is way ahead of you and his/her project looks pretty good. Use the Asking for Help Skill. The target skills (see Supporting Information) were selected from Teaching Social Skills to Youth (Dowd & Tierney, 2005). Two social skills, with four steps each, were targeted: joining in a conversation and asking for help. Twenty-five vignettes were written targeting joining in a conversation, which was targeted in training sessions, and five vignettes were written to focus on asking for help, which was included in generalization probes. Vignettes were randomly selected and presented throughout all phases of the study; however, one vignette was used repeatedly as part of the training phase. At the beginning of the study, the order of the vignettes was determined using a random sequence generator (available at www.random.org). Graduate students played the role of the conversational partner described in the vignettes to guarantee there were sufficient individuals to perform the skill. When the child performed the desired skill (i.e., by joining in a conversation or asking for help), the graduate student, principle investigator (PI), or parent (depending on the phase) would allow for natural consequences to occur, such as continuing the conversation, asking a follow up question, or providing assistance in answering a question. Baseline (BL). During baseline, as well as all subsequent phases, parents were asked to demonstrate, to the best of their ability, how they would teach their child each social skill. Each parent was informed that in addition to their child, they could also interact with the principal investigator (PI) and research assistants to aid in role-play. Parents were also provided a vignette as well as the social skill sheet, a document that stated the name of the skill to be taught and listed its steps. If a parent failed to provide an opportunity for her child to demonstrate the social skill as part of a role-play component (i.e., failed to perform step 11), the PI used previously developed scripts to provide an occasion for skill demonstration. If a parent simply read the skill name and corresponding steps (i.e., “Join in a conversation by looking at the people who are talking, waiting for a point when no one else is talking, making a short, relevant comment that relates to the topic discussed, and giving other people a chance to participate”), it did not count as providing an opportunity for skill demonstration, because there was no contrived PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST conversation to join in. Therefore, to determine if the child already had the skill in his repertoire, the experimenter used preselected scripts that included a contrived yet seemingly ordinary opportunity for the child to display each of the skills. For instance, the child was asked to sit at the table while the PI and parent discussed upcoming holiday plans, providing an opportunity for the child to join in the conversation. Training. During the training phase, each parent was taught how to use BST to teach a specific social skill to her child. The child was not present. The PI started by explaining the roles of the individuals present and the sequence of the training. For instance, the PI would say: “First, I will show you how to teach social skills with you playing the role of the child and myself playing the role of the instructor. Later, we will switch and you will play the role of the instructor.” Training took place during one session at the parent’s home. One training vignette was used (i.e., “Your grandma is talking with ____________ about going to the grocery store and picking out something for dinner. You want to go too because you think _______ would be a great idea for dinner. Use the joining in a conversation skill”). Instructions. The BST handout (see Supplemental Information) was introduced as part of the training phase and made available to each parent during all remaining phases of the study. The PI reviewed the BST handout and then instructed the parent on how to correctly use the BST steps to teach a specific social skill. Parents were also encouraged, but not required, to provide attention (e.g., praise, touch) and small rewards (e.g., snacks, breaks, access to toys) contingent on compliant behaviors. Modeling. Following the instruction component, each parent observed the PI and two graduate students as they modeled the correct use of the BST steps using the training vignette. One graduate student used a puppet to ensure that there were sufficient 811 conversational partners to demonstrate the target skill (i.e., joining in a conversation). Next, the PI modeled the entire BST method, one step at a time, while the parent played the role of the child. This included providing the parent (playing the role of the child) with appropriate feedback in the form of descriptive praise for skills demonstrated correctly and corrective feedback on steps not demonstrated correctly or missed. Role-play. After the PI reviewed the BST steps, the parent and PI switched roles (i.e., PI played the role of the child and the parent played the role of the instructor), and the parent used BST to teach the PI the targeted skill. At this time, novel vignettes were provided to the parent and data were collected on correct teaching steps. Feedback. Following the role-play, the PI provided the parent (playing the role of the instructor) with the same form of feedback that was delivered as part of the modeling component. The parent moved on to the next phase (parent–child posttraining) after the following mastery criteria were met: (a) parent met or exceeded an 80% level of proficiency of correct teaching steps across three consecutive trials using three novel vignettes; (b) parent demonstrated the use of all required steps; and (c) for those parents who were administered the maintenance probe, parents continued to demonstrate an 80% level of proficiency of correct teaching steps. If parents did not meet the criteria during the training session, they were required to complete a training booster session. Training booster sessions (T-B). The training booster (T-B) phase consisted of a supplementary training phase that involved two additional opportunities for the parent to rehearse the BST steps with the training vignette while playing the role of the instructor (with the PI playing the role of the child). The PI provided feedback in the same way as during initial training. The instruction and modeling components were not included. 812 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. Maintenance probe (M). The maintenance probe was mandatory if more than one day had elapsed between the training or T-B session and the parent–child posttraining phase (PostT). In these cases, two maintenance probes were conducted at the beginning of the session to assess if the skills had maintained. During the maintenance probes, the parent was given novel vignettes and asked to teach the skill to the PI who played the role of the child. If previously acquired skills were maintained, the parent moved on to the parent–child posttraining phase. Two parents (Hana and Kathy) required the maintenance probes, and both met criteria to move on. Self-monitoring procedure (SM). A selfmonitoring procedure was implemented if parents failed to meet training criteria following training and the T-B session. This modified procedure required parents to physically check off each step as completed, on the BST Handout. If a parent failed to mark a step, the PI stated, “Please place a checkmark in the box when you have correctly completed the step.” No other feedback was provided. Parent–child posttraining (Post-T). After she had met training mastery criteria, the parent began using the treatment package consisting of a BST handout, the social skill sheet with steps, and a vignette, to teach her child the target social skill. Mastery criteria for parent–child posttraining were the same as in other phases for the parent. In addition, we required that the child achieved at least 80% of steps correct across three trials. If the parent failed to meet criterion, the self-monitoring procedure (PostSM) was implemented, and at least three additional trials took place. If the child’s responding did not meet criteria, two additional trials took place. Generalization. The parent was provided with the materials (BST handout, social skill sheet with steps, and a vignette) and given an opportunity to teach her child the untrained skill (i.e., asking for help). Probe data were collected to determine if parents would correctly use the BST steps to teach their child a novel social skill. The following skills were selected by Hana, Shari, Abby, and Kathy, respectively: (1) introducing yourself (five steps), (2) correcting another person (six steps), (3) waiting your turn (five steps), and (4) interrupting appropriately (five steps). Follow-up. Follow-up was implemented 1 month after the completion of the parent– child posttraining phase. The parent was provided the opportunity to teach the trained and untrained skills. In addition, the parents were given the opportunity to teach a social skill of their own selection. The parents had previously (following the final parent–child posttraining session) been asked to select a skill to teach from Teaching Social Skills to Youth (Dowd & Tierney, 2005). The skill had to include four to six steps and be directly from the book. They had the opportunity to practice, on their own and without feedback, between the final Post-T session and the follow-up session. RESULTS Figure 1 shows both the percentage of BST steps correct overall as well as the percentage of required steps correct, for all parents. During the baseline phase, all parents displayed very few correct teaching steps (range, 0%–13%). The BST intervention package (i.e., training session) increased correct teaching of target social skills for all parents. During the first training phase, the percentage of correct BST steps increased for all parents (range, 77%– 97%). Kathy met mastery criteria during the first training phase, and Hana met mastery criteria during the initial T-B session. Shari and Abby required the self-monitoring procedure (SM) before meeting criteria. Furthermore, parents displayed high integrity when performing the required steps, which were rated as critical components of BST by professionals. Total trials of training (excluding the generalization PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST Parent Percentage of BST Steps with Correct Teaching BL T-B Training M Post-Training Follow up 100 90 80 Required Parent 70 BST Step Selected Skill Probe 60 Trained 50 Skill 40 30 Generalization 20 Skill Probe 10 0 Hana -10 PostT-B SM Post-SM Training 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Shari -10 T-B SM Post-Training 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 Abby M 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Post-Training Kathy 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Trials Figure 1. Percentages of parent correct teaching and required steps across phases. probes) were six for Hana, nine for Shari, nine for Abby, and three for Kathy. Each phase was completed in one session, with the exception of 813 the additional self-monitoring protocol used with Shari (during training and parent–child posttraining) and Abby (during training). During the parent–child posttraining sessions, Hana, Abby, and Kathy met the mastery criteria within the first three trials, with mean correct teaching steps of 100% (Hana), 95% (Abby), and 84% (Kathy). One parent (Shari) required the additional self-monitoring procedure (Post-SM). This resulted in an increase in her performance of correct teaching steps to an average of 95%. Overall, the correct teaching steps for Hana, Shari, Abby, and Kathy increased by 96%, 86%, 88%, and 82%, respectively, when comparing scores in baseline and posttraining phases. See Supporting Information for a fine-grained analysis of results for individual BST steps. Figure 2 displays percentages of steps correct for the child participants. During baseline, none of the parents provided an opportunity for their child to practice the target skill (i.e., joining in a conversation). Therefore, the experimenters used preselected scenarios to create consistent opportunities for skill demonstration. When the children were provided the opportunity to demonstrate the joining-in-aconversation skill, most emitted few correct steps, with the average percentage of correct steps for Carter, James, Eric, and Sam being 12%, 50%, 35%, and 33%, respectively. During the Post-T sessions, when the parents taught their children, only Carter met the mastery criterion (i.e., 100% or higher on posttraining trials, meaning children had to display all correct steps). Nevertheless, parentimplemented BST increased child percentage of correct steps by approximately 88% (Carter), 25% (James), 55% (Eric), and 12% (Sam). Carter’s data were relatively stable in baseline and Post-T phases, with a clear level change from one phase to another. James’ data indicated a potentially decreasing trend in baseline, but overall higher levels during the parent– child posttraining phase. Eric’s data showed an REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. 814 BL Child Percentage of Steps Correct 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 Post-Training Follow up Parent Selected Skill Probe Trained Skill Generalization Skill Probe Carter 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 0 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 0 James Eric 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sam 2 4 6 8 10 Trials 12 14 16 18 Figure 2. Percentages of child correct performance of skills across phases. increasing trend during baseline, rendering level change from baseline to Post-T difficult to interpret. Lastly, Sam’s data showed a prominent decreasing trend in baseline, and an increasing trend and clear level change in the parent–child posttraining phase. Generalization and Follow-up Data Baseline generalization probes yielded few correct target behaviors for parents and children. The percentage of BST steps correct ranged from 0% - 13% across parents (Figure 1). The percentage of target skill steps correct was 0% for all children (Figure 2). When the generalization probe was administered in the Post-T phase, correct responding increased for both parents and children. For the parents, the percentage of steps correct ranged from 86% to 100%, and for the children, the percentage of steps correct ranged from 75% to 100% during Post-T. The BST skills maintained for all four parents during the follow-up session, with a range of 80% - 100% across participants for the trained skill, and 60% - 93% for the untrained skill targeted in the generalization probes (Figure 1). For the child participants, the trained skill maintained for Carter, James, and Sam, whose percent correct ranged from 75% to 100%. Eric, who had an average score of 90% during the training phase, displayed a slight decrease at follow-up (75%). Maintenance of the untrained skill was slightly lower for all four child participants, with a range of 50% - 75% across participants. We could not collect data for James during the generalization probe in the follow-up phase, because his mother did not provide an opportunity for role-play during the rehearsal phase. Direct observation of parent and child behavior with a parent-selected skill was included in the follow-up assessment. Correct teaching steps for the parent-selected skill for Hana, Shari, Abby, and Kathy were 86%, 93%, 93%, and 60%, respectively. Kathy failed to provide Sam with an opportunity for skill demonstration, which contributed to her low score. For that reason, data for the parentselected skill are not presented for Sam in Figure 2. Carter, James, and Eric performed the parent-selected skill with an accuracy of 80%, 66%, and 100%, respectively. PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST Social Validation of Training The modified version of the TEF–SF with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree) was completed by all parents at posttreatment and follow-up. Average parent ratings of BST scores (posttreatment; follow-up) were: acceptability of BST (5; 5), willingness to use BST (5; 5), likeability of procedure (5; 4.75), belief that child did not experience discomfort (4.25; 4.25), found BST resulted in meaningful change (4; 4.50), and positive reaction to BST (4.75; 4.75). DISCUSSION We evaluated the use of instructions, modeling, role-play, and feedback to teach parents to use Behavioral Skills Training (BST) to implement social-skill instruction with their children with autism. The intervention was effective in increasing the parents’ correct use of BST for social skills instruction, and performance gains generalized to a social skill that had not been included in training. Furthermore, the parents were able to use BST to implement instruction with a novel, parent-selected social skill, with moderate to high accuracy. Although most children did not meet the criterion level for mastery, they displayed an increase in the number of correctly performed steps with both the trained and untrained skills. Parents and children also continued to display these skills at follow-up, 1 month later. Furthermore, parents reported high satisfaction ratings when evaluating the BST intervention. Similar to Stewart et al. (2007), the present study indicated that family members can learn BST skills in a short period of time, and use BST to teach their children social skills. Parents responded to BST differently; some individuals required more training than others. However, even Shari, who required the longest training and Post-T phase duration, still met mastery criteria in a relatively short period of time (i.e., three 2-hr sessions). The current study 815 supports previous research demonstrating that improvements in children’s social skills can occur as a function of caregiver-implemented BST; however, longer posttreatment phases are needed to fully evaluate acquisition and maintenance (Stewart et al., 2007). Consistent with previous literature, the current study suggests that BST can be used to teach novel skills in a brief period of time (Himle et al., 2004; Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010; Toelken & Miltenberger, 2012). Each parent was able to increase their child’s correct number of steps for the targeted social skill (joining in a conversation) in a relatively short period of time (i.e., 20 - 40 min). It is likely that with more practice, all children would have achieved mastery. Future studies should include a more thorough evaluation of child performance by increasing the duration of the parent-implemented social skills instruction to assess what variations or modifications to the protocol are required to increase skill acquisition. Limitations of the current study warrant consideration. First, the four basic components of BST were extended to 15 precisely defined steps for data collection purposes. However, some of the steps may be unnecessary (e.g., brief quiz, behavior-specific praise), and future research may consider a component analysis to determine the compulsory steps (see Table 1). Second, because strict operational definitions were used to define the skill steps and stringent criteria were set for parent and child behavior, flexibility and creativity of parent behavior was limited. Third, for child participants, the mastery criterion for correct steps was 100%; however, given such a brief training period a less stringent criterion would have been more appropriate. The increasing trend in Eric’s baseline and decreasing trend in Sam’s baseline make it more challenging to interpret their data. It is possible that fluctuations in motivating operations accounted for some of this variability. In 816 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. Table 1 BST Steps and Definitions Dependent Measures Instruction 1) Rationale 2) State all steps 3) Chance to ask questions 4) Brief quiz Modeling Phase 1) Introduction to modeling phase 2) Read vignette 3) Skill demonstration 4) Review modeled steps 5) Chance to ask questions Rehearsal Phase 1. Introduction to rehearsal phase 2. Opportunity for rehearsal Feedback Phase 1. Immediate feedback 2. Behavior-specific >1 3. More praise then correctives 4. If a step was missed, repeat rehearsal component Operational Definition Parent states the name of the skill and gives at least one reason why the skill is important Parent states all steps (in order) included in skill Parent asks the child if he/she has any questions Parent asks the child to recite the steps associated with skill Parent states they will demonstrate the skill while child watches Parent reads vignette or describes scenario similar to vignette Parent demonstrates steps (models correct and/or correct/incorrect behaviors) Parent explains what steps were demonstrated correctly (or incorrectly and how they should have been displayed) Parent asks the child if he/she has any questions Parent states that the child is to practice the skill Parent reads vignette or describes scenario, have at least 1 conversational exchange and allow ≥1 sec pause for child to comment Parent must provide feedback within 10s Parent states 2 positive behaviors the child displayed (about steps or nonverbal behavior) Total praise statements must be > than corrective Parent provides corrective feedback on missed step and repeats rehearsal component * Required steps are italicized. other words, parent choice of potential reinforcers or lack of clear contingencies for participation may have influenced the children’s motivation to respond with their best effort. The majority of previous social skills training research has focused on positive nonverbal behaviors (e.g., eye contact) and vocal verbal behaviors, such as initiation of speech (Matson, Matson, & Rivet, 2007). Therefore, similar social skills were selected as target behaviors in the current study. These behaviors are significant to this population, because impairments in these areas are critical for diagnosis and influence the development and sustainability of social relations (Owens, Granader, Humphrey, & Baron-Cohen, 2008; White, Keonig, & Scahill, 2007). Further studies should evaluate the effects of parent-implemented BST on more intermediate or advanced level skills (e.g., interrupting appropriately; accepting defeat or loss). Finally, future studies should collect follow-up data to evaluate greater maintenance of acquired skills. In conclusion, training parents to be social skills trainers through the use of a BST model may empower parents to work independently and effectively with their own children, and allow them to substitute or add new skills of varying difficulty as their children age and mature. The simplicity, practicality, and straightforwardness of the BST handout (see Supplemental Information) may allow for its use by not only parents but also other caregivers (e.g., grandparents, teachers, babysitters) who spend time with children. Services for children with autism remain difficult for many families to access or afford. The simple nature of the BST method increases the likelihood that social skills training could be implemented in the home, group clinical settings, and school settings. It also has proven to be an efficient approach to teaching skills within a short period of time. Moreover, the simple and straightforward language used in the BST handout should allow for it to be easily understood by nonexperts and translated into a PARENT-IMPLEMENTED BST wide range of languages to reach larger populations. REFERENCES Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology. Crane, D. R. (1995). Introduction to behavioural family therapy for families with young children. Journal of Family Therapy, 17, 229-242. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1467-6427.1995.tb00015.x Crockett, J., & Hird, O. (2009). The effects of project SafeCare on the parenting skills of a mother with an intellectual disability. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development, 2, 73-81. Crosby, J. W. (2011). Test review: F. M. Gresham & S. N. Elliott Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, 2008. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29, 292-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910385806 Dowd, T., & Tierney, J. (2005). Teaching social skills to youth. Boys Town, NE: Boys Town Press. Forehand, R., Sturgis, E. T., McMahon, R. J., Aguar, D., Green, K., Wells, K. C., & Breiner, J. (1979). Parent behavioral training to modify child noncompliance. Treatment generalization across time and from home to school. Behavior Modification, 3, 3-25. https://doi. org/10.1177/014544557931001 Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social skills improvement system rating scales manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson. Gross, A., Miltenberger, R., Knudson, P., Bosch, A., & Brower Breitwieser, C. (2007). Preliminary evaluation of a parent training program to prevent gun play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 691695. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2007.691-695 Himle, M. B., Miltenberger, R. G., Flessner, C., & Gatheridge, B. (2004). Teaching safety skills to children to prevent gun play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2004. 37-1 Hsieh, H., Wilder, D. A., & Abellon, O. E. (2011). The effects of training on caregiver implementation of incidental teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 199-203. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba. 2011.44-199 Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 259-273. https://doi.org/10. 1901/jaba.1980.13-259 Kelley, M. L., Heffer, R. W., Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1989). Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 11, 235-247. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00960495 817 Lafasakis, M., & Sturmey, P. (2007). Training parent implementation of discrete-trial teaching: Effects on generalization of parent teaching and child correct responding. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 685-689. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2007.685-689 Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., & Risi, S. (2000). Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. Magen, R. H., & Rose, S. D. (1994). Parents in groups: Problem solving versus behavioral skill training. Research on Social Work Practice, 4, 172-191. https:// doi.org/10.1177/104973159400400204 Matson, J. L., Matson, M. L., & Rivet, T. T. (2007). Social-skills treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders: An overview. Behavior Modification, 31, 682-701. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0145445507301650 Matson, M. L., Mahan, S., & Matson, J. L. (2009). Parent training: A review of methods for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 868-875. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.rasd.2009.01.001 McMahon, R. J., & Forehand, R. (2003). Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. McNeil, C. B., & Hembree-Kigin, T. L. (2010). Parentchild interaction therapy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. Miles, N. I., & Wilder, D. A. (2009). The effects of behavioral skills training on caregiver implementation of guided compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 405-410. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba. 2009.42-405 Nakamura, B. J., Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., & Chorpita, B. F. (2009). A psychometric analysis of the Child Behavior Checklist DSM-Oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 3, 178-189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-0089119-8 Nigro-Bruzzi, D., & Sturmey, P. (2010). The effects of behavioral skills training on mand training by staff and unprompted vocal mands by children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43, 757-761. https://doi. org/10.1901/jaba.2010.43-757 Owens, G., Granader, Y., Humphrey, A., & BaronCohen, S. (2008). LEGO therapy and the social use of language programme: An evaluation of two social skills interventions for children with high functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1944-1957. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10803-008-0590-6 Shriver, M. D. & Allen, K. D. (2008). Working with parents of noncompliant children (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Stewart, K. K., Carr, J. E., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2007). Evaluation of family-implemented behavioral skills training for teaching social skills to a child with Asperger’s 818 REBECCA K. DOGAN et al. disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 6, 252-262. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1534650106286940 Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349-367. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba. 1977.10-349 Toelken, S., & Miltenberger, R. G. (2012). Increasing independence among children diagnosed with autism using a brief embedded teaching strategy. Behavioral Interventions, 27, 93-104. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bin.337 Vernon, D. S., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (1996). The SCORE skills: Social skills for cooperative groups. Lawrence, KS: Edge Enterprises. Watson, P. J., & Workman, E. A. (1981). The nonconcurrent multiple baseline across-individuals design: An extension of the traditional multiple baseline design. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 12, 257-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/ 0005-7916(81)90055-0 White, S. W., Keonig, K., & Scahill, L. (2007). Social skills development in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the intervention research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1858-1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10803-006-0320-x Received May 18, 2014 Final acceptance September 26, 2015 Action Editor, Einar Ingvarsson SUPPORTING INFORMATION Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.