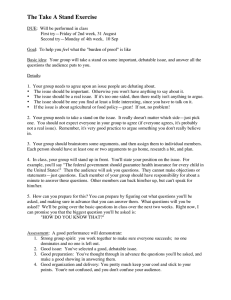

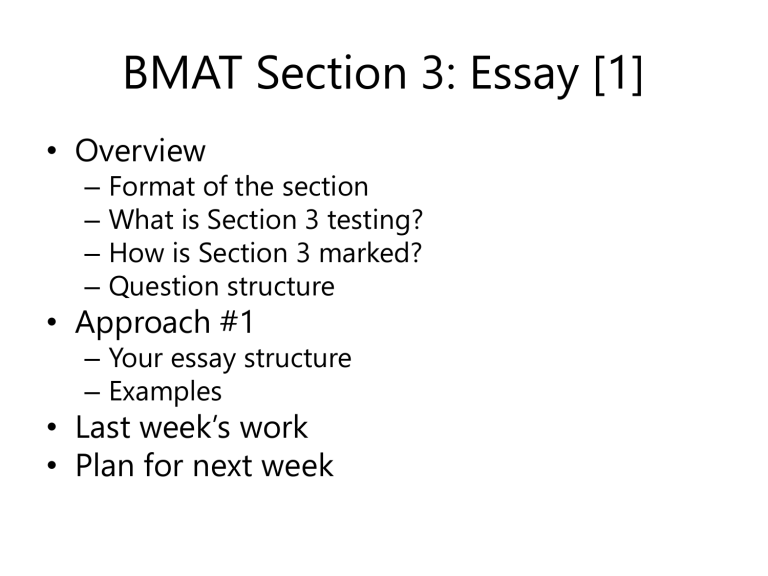

BMAT Section 3: Essay [1] • Overview – – – – Format of the section What is Section 3 testing? How is Section 3 marked? Question structure • Approach #1 – Your essay structure – Examples • Last week’s work • Plan for next week Format of the section • Presented – Three statements: quotations or opinions expressed as if they were facts – Instructions: • Explain the statement. • Formulate an objective argument. • Express your opinion. • Expected – Write one essay, addressing one particular statement/quotation – On one side of A4 paper • Allowed – Notes on a separate sheet of paper. What is Section 3 testing? • The BMAT guidelines – ‘This section tests ability to select, develop and organise ideas and communicate them in writing in a concise and effective way.’ – ≠ ‘being creative’ – You want to appear: logical, concise, reasoned and systematic, like a scientist. How is Section 3 marked? • Content: scoring-a-5 checklist – – – – – – – All aspects of the question are addressed Excellent use of the material Excellent counter-proposition or argument The argument is cogent Clear and logical Breadth of relevant points Compelling conclusion – – – – – – Fluent Good sentence structure Good use of vocabulary Sound use of grammar Good spelling and punctuation Few slips or errors • English: scoring-an-A checklist Question structure • Answer only one question out of three • Each question – A statement or quotation – Prompts • Explain the statement. • Provide objective arguments. • Reach a balanced conclusion. • The most common question – – – – Statement or Quotation Explain the statement. Argue to the contrary of / argue for the statement. To what extent do you agree with the statement / what is your opinion on the subject of the statement or quotation? Your essay structure • One suggestion: Section • 11–18 Sentence s Words Explanation 1-2 20-40 Objective argument 5-8 130-180 Extent of argument sentences 5-8 130-180 11-18 280-400 Total: are not many. – The essay doesn’t have to be long. – Every single sentence is crucial. Don’t waste words! Sentence structure • Keep it simple! – Writing short, punchy sentences will ensure maximum clarity and impact. • Examples – It is important to practise BMAT Section 3 because it is one of the most challenging sections of the exam and offers a chance for candidates to stand out but it is also important to practise other sections of the exam and overall exam technique. – It is important to practise BMAT Section 3 because it is one of the most challenging sections of the exam. It therefore offers a chance for candidates to stand out. However, it is also important to practise other sections of the exam, in addition to overall exam technique. The statement/quotation • Often science- or medicine-related • Not highly technical • In general, there are two types of statement: – An opinion stated as fact • In a world where we struggle to feed an ever-expanding human population, owning pets cannot be justified. (2013) – A quotation • ‘The art of medicine consists of amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.’ Voltaire. (2011) • Which one to tackle? – Select one which you not only understand perfectly but are actually interested in Explaining the statement/quotation [1] • The first part of the task can be phrased in slightly different ways. – – – – – ‘Explain what this statement means.’ ‘Explain what you think the above means.’ ‘What does the above imply?’ ‘What do you understand by the above?’ ‘Explain the argument behind the above.’ • Response: a couple of sentences – Absolutely critical – The rest rests upon this. – Any misunderstandings are likely to be transmitted – and magnified – throughout your Explaining the statement/quotation [2] • How? – Identify the key terms. – Define these key terms. • Write what is meant by the key terms, without using the term itself. – Apply context and combine. • Fuse together these definitions. • Provide a cohesive overall meaning in one or two sentences. • A worked example ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Darwin Step one – identify the key terms [Q] ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Darwin • Which are the key terms that give the statement its meaning? – Which terms do you need to ‘translate’ to explain to someone, in a different (preferably simpler) way? – What exactly is Darwin getting at? Step one – identify the key terms [A] ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Darwin • Which are the key terms that give the statement its meaning? – Which terms do you need to ‘translate’ to explain to someone, in a different (preferably simpler) way? – What exactly is Darwin getting at? ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Step two – define these key terms Not necessarily a dictionary definition. • • Make it easily comprehensible, while accounting for the context. – Do not try to impress by using overcomplicated language. – Clarity is always the goal. • ‘Scientific man’ – Person seriously involved in scientific pursuits • ‘Ought’ – Should/ideally • ‘Wishes/affections’ – Emotional traits • ‘Heart of stone’ Step three – apply context and combine ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Darwin • ‘Scientific man’ – Person seriously involved in scientific pursuits • ‘Ought’ – Should/ideally • ‘Wishes/affections’ – Emotional traits • ‘Heart of stone’ – Metaphor for emotional detachment • Fusing together the definitions. ‘Charles Darwin is suggesting that a person who is seriously practising science would, in an ideal world, be completely free from emotion.’ (21 words) Explaining the statement/quotation [3] • Variations: ‘explain the reasoning’ behind the statement. – Adjust your approach slightly. – Stick to the same three-step plan above, but add a layer of interpretation. – Go one step further, suggesting the rationale behind the statement. ‘A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections – a mere heart of stone.’ Charles Darwin ‘Charles Darwin is suggesting that a person who is seriously practising science would, in an ideal world, be completely free from emotion. The reasoning behind this statement might well be that, since science is by definition objective and precise, the fickle nature of Argue objectively [1] • The second part will almost always demand an objective argument. – Argue against (‘to the contrary of’) the statement – Argue for the statement – Argue both for and against the statement • How? – Try to come up with two or three clearly and logically articulated arguments, each demonstrated by a strong example. Argue objectively [2] • A worked example ‘The art of medicine consists of amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.’ Voltaire Argue to the contrary that medicine does in fact do more than amuse the patient. ‘Voltaire implies that the key skills involved in medicine are those that simply reassure or distract the patient, while their ailment corrects itself naturally over time.’ • Note – ‘amusing’, in this context, is equated to reassuring and distracting the patient. • Not the modern definition making someone laugh. – Context is crucial Argue objectively [3] ‘The art of medicine consists of amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.’ Voltaire Argue to the contrary that medicine does in fact do more than amuse the patient. • In the plan: an prompt followed by an example – Emergency surgery – e.g. stent in coronary artery – Faster healing – e.g. orthopaedic gamma nail – Prescribing medication – e.g. HIV • On the paper Contrary to Voltaire’s statement, there are many instances in which medicine does more than amuse the patient. This is often true of medical procedures that have been scientifically proven to physically improve patients’ well-being faster, or more dramatically, than nature. This is certainly the case in emergency procedures, such as the insertion of a stent into one of the coronary arteries of the heart in order to relieve an acute blockage to blood flow. It is also true of procedures which speed up healing, like the insertion of an orthopaedic gamma nail, which can realign a fracture of the lower limb with much faster and more consistent results than could realistically be expected to occur naturally. Argue objectively [4] • Argue objectively: your personal opinion is not relevant – yet! – Relevant later: ‘to what extent you agree’ – Phrases like ‘I think’ and ‘in my opinion’ are not appropriate at this stage. • Tailor your language accordingly. – Words for objective arguments e.g. therefore, however, in light of, consequently, for example, for instance • You may well get asked to ‘argue for’ a statement. – Simply apply the above methodology, but note arguments ‘for’ rather than arguments ‘against’. To what extent do you agree? [1] • The final part prompts expression of an opinion. – Ask: ‘to what extent do you agree that…’ followed by a paraphrasing of the statement/quotation. • How? – Previous part: just put forward some objective arguments ‘for’ or ‘against – To conclude the extent to which you agree, you could begin by counterbalancing those arguments. – Now, you will be well positioned to make a wellbalanced conclusion. • Appreciate that there are merits to both sides. To what extent do you agree? [2] • The worked example ‘The art of medicine consists of amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.’ Voltaire To what extent do you think Voltaire is correct? • Think of arguments in favour – already provided arguments to the contrary. – ‘Amusing’ in this context can equate to ‘listening to’, or ‘sympathising with’, a patient – There is an art to this – Nature can cure many ailments (e.g. common cold) • Weigh these against our previous arguments to the contrary. – In some conditions, the emphasis is on ‘amusing’ the To what extent do you agree? [3] • Writing up the counterbalancing arguments and the conclusion: Nonetheless, Voltaire’s standpoint is not without merit. In this context, ‘amusing’ the patient can be taken to mean ‘offering sympathy’ or ‘reassuring’ them. There is clearly an art to this and it is extremely valuable in medicine. For example, in the case of the common cold, there is little a doctor can do to help medically. But the doctor can reassure the patient that there is nothing seriously wrong, and that they will be well again soon. Overall, there are some times when the best thing a doctor can do is to ‘amuse’, or ‘reassure’, a patient while nature takes its course. At other times, though, medical procedures or prescriptions must be administered to prevent an illness progressing. Perhaps we can conclude that the best doctors are those who combine the ‘art’ of sympathy and reassurance with the ‘science’ of swiftly applying necessary physical procedures. (144 words) • Note Timing: step-by-step approach • To be continued…