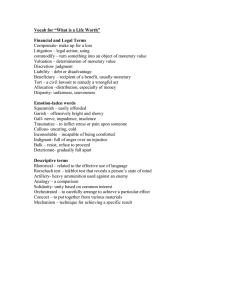

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1743-9132.htm Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity Van Dan Dang Department of Finance, Banking University of Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and Khac Quoc Bao Nguyen School of Finance, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam 619 Received 10 June 2020 Revised 14 July 2020 22 August 2020 Accepted 3 September 2020 Abstract Purpose – The study explores how banks design their financial structure and asset portfolio in response to monetary policy changes. Design/methodology/approach – The authors conduct the research design for the Vietnamese banking market during 2007–2018. To ensure robust findings, the authors employ two econometric models of static and dynamic panels, multiple monetary policy indicators and alternative measures of bank leverage and liquidity. Findings – Banks respond to monetary expansion by raising their financial leverage on the liability side and cutting their liquidity positions on the asset side. Further analysis suggests that larger banks’ financial leverage is more responsive to monetary policy changes, while smaller banks strengthen the potency of monetary policy transmission toward bank liquidity. Additionally, the authors document that lower interest rates induce a beneficial effect on the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) under Basel III guidelines, implying that banks appear to modify the composition of liabilities to improve the stability of funding sources. Originality/value – The study is the first attempt to simultaneously examine the impacts of monetary policy on both sides of bank balance sheets, across various banks of different sizes under a multiple-tool monetary regime. Besides, understanding how banks organize their stable funding sources and illiquid assets amid monetary shocks is an innovation of this study. Keywords Bank leverage, Bank liquidity, Monetary policy, Net stable funding ratio Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Fundamentally, monetary policy is implemented to stabilize the price level and support economic growth reasonably. Using multiple monetary tools, central banks could achieve various transmission targets through the banking system. However, after witnessing the incidents and consequences of the global financial crisis, one attributes monetary policy to be one of the critical constituents adding to the instability of the whole financial sector (Taylor, 2011). In this regard, monetary policy could induce numerous adverse effects on bank risk, forming the bank risk-taking channel, mainly due to changing banks’ risk tolerance and perception originated by interest rate fluctuations (Adrian and Shin, 2010; Borio and Zhu, 2012). More seriously, practical concerns have been raised, and central banks are called for tightening monetary policy to restrain banks’ risk-taking desires (Acharya and Naqvi, 2012; Diamond and Rajan, 2012). Therefore, the impact of monetary policy on bank risk-taking becomes an important research topic that deserves more investigations. The impact of monetary policy on bank risk-taking has recently been extensively discussed in the literature, attracting much attention from scholars and policymakers. However, the insight on this nexus has been limited in content and context, as reflected in two important directions. First, many studies establish the bank risk-taking channel’s functioning from the perspective of the credit portfolio quality and bank-level financial JEL Classification — E52, E58, G21 International Journal of Managerial Finance Vol. 17 No. 4, 2021 pp. 619-639 © Emerald Publishing Limited 1743-9132 DOI 10.1108/IJMF-06-2020-0284 IJMF 17,4 620 stability. Meanwhile, only a few studies focus on how monetary policy drives separate sides of bank balance sheets. Particularly, the stability of funding is not yet considered. Second, the existing research is mostly interested in advanced economies, highlighted by a near-zero or negative interest rate environment (Altunbas et al., 2014; Delis and Kouretas, 2011; Jimenez et al., 2014; Maddaloni and Peydro, 2011). It should be noted that these economies differ considerably from emerging markets in mature levels, regulatory frameworks and especially the working of monetary policy [1]. To fill the gap in the literature, we empirically examine the effects of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity. Theories predict that monetary policy may influence both sides of bank balance sheets. For example, on the liability side, monetary expansion lowers banks’ funding costs and thus promotes higher leverage (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2014; Valencia, 2014) [2]. On the asset side, lower interest rates boost the “search for yield” incentive if banks have a fixed revenue target, thus encouraging them to reduce the holdings of liquid assets (Borio and Zhu, 2012; Rajan, 2006). The empirical literature studying these mechanisms with banking data is still limited. Therefore, an in-depth analysis on the simultaneous effects of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity is the first attempt contributing to the literature stream on the banking channels of monetary policy transmission. When examining the effects of monetary policy on bank risk-taking behavior, prior documents have commonly taken into account the difference in the bank financial strength as vital moderators (Gambacorta and Marques-Ibanez, 2011; Kashyap and Stein, 2000; Khan et al., 2016; Kishan and Opiela, 2006). In this stream, bank size is the most widely considered factor. The rationale is that prior analysis relies on the capacity of increasing external funding to explain bank behavior during monetary policy fluctuations. It hypothesizes that large banks may be less affected by monetary shocks since they have lower external funding costs. Therefore, motivated by this stylized fact, we further pay attention to the moderating role of bank size in the current relationships investigated. Our findings could affirm or contradict existing speculations, thereby enriching the bank risk-taking channel with new perspectives. Additionally, taking a step further in this study, we use an indicator describing bank funding stability in relation to asset illiquidity to investigate a novel impact of monetary policy on bank behavior. Angeloni et al. (2015) theorize that relaxing monetary policy may modify the composition of bank liabilities, particularly reconstructing stable funding sources. To this end, we employ the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) introduced by Basel III guidelines. In the empirical studies of monetary transmission through the banking system, the NSFR indicator was used in regressions of the bank lending channel, but only to estimate how changes in bank liquidity risk alter the potency of the transmission (Giordana and Schumacher, 2013), not concentrating on how monetary policy may itself affect this indicator. Hence, understanding how banks organize their stable funding in relation to illiquid assets during monetary policy shocks, based on Basel III guidelines, is a key contribution of this study. We conduct our research design for the Vietnamese banking market, gathering data from 2007 to 2018. Based on multiple aspects, Vietnam offers a favorable laboratory to examine the present issue. First, the economy of Vietnam heavily depends on banks and their lending activities, which makes the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission through the banking sector more pronounced. Second, the Vietnamese banking sector has experienced major reforms in recent years, featured by the expansion of bank assets, increased equity and improved liquidity. During this process, large banks have always dominated the market (Batten and Vo, 2016; Le, 2017). Third, the monetary policy in Vietnam exhibits unique characteristics. In principle, reserve requirements and base interest rates are assumed as the primary tools of monetary policy but remain invariant for a prolonged time. In practice, the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) applies a series of policy rates and administrative controls to regulate the interest rate framework, which has never been close to zero-bound. We organize the remainder of this study as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature. Section 3 exhibits the relevant background of the Vietnamese banking industry and monetary policy regime. Section 4 presents the empirical strategy, including the variable construction, model specification and econometric technique. Section 5 reports and discusses the estimation results, and Section 6 concludes and indicates some implications. 2. Related literature Generally, the literature on the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission agrees that monetary expansion exerts a negative effect on banks’ risk perception and risk tolerance (Adrian and Shin, 2010; Borio and Zhu, 2012). Examining bank balance sheets, scholars establish two primary routes through which monetary policy could drive bank risktaking. The first operates on the liability side of bank balance sheets. A drop in interest rates reduces funding costs, which is a crucial determinant of bank funding structure, hence encouraging banks to produce higher financial leverage. This theory is modeled by Dell’Ariccia et al. (2014) and Valencia (2014), confidently concluding that monetary policy induces banks to modify their leverage, which, in turn, adjusts bank risk-taking levels. Angeloni et al. (2015) also elaborate that monetary expansion may alter the composition of bank liabilities, particularly reconstructing the stable funding sources. The second route acts through the asset side of bank balance sheets. In this vein, the impact of monetary policy is shown in the form of asset portfolio reallocation. Monetary expansion signals the declined yields of safe assets. These declines lower bank returns, thus leading banks to raise their demand for higher yield risky assets to substitute highly liquid and low-risk assets (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2014). This mechanism is more conspicuous in case the performance target of banks is sticky, which makes bank managers have more incentives to move toward riskier credit segments, proposing the so-called “search for yield” incentive (Borio and Zhu, 2012; Diamond and Rajan, 2005). Moreover, during monetary policy expansion, banks tend to prefer long-term loans (Diamond and Rajan, 2006). As a result, bank illiquidity rises. It should be taken into consideration that bank risk-taking on the liability side initiates and magnifies bank risk-taking on the asset side. Precisely, with higher leverage that implies bank risk-shifting to other creditors, the preference of banks for risky investments grows given the bounded losses (Angeloni et al., 2015; Valencia, 2014). However, monetary policy easing could also generate alternative impacts. Smith (2002) theorizes that higher interest rates elevate banks’ opportunity costs or, in other words, cash holding costs, which discourages banks from holding liquid assets. Kane (1989) claims that banks would find risky assets and the “gambling for resurrection” strategy more appealing after increased interest rates cause a decline in their net worth. In another vein, increased interest rates could lower the franchise value via improved bank profits, thus mitigating the moral hazard problem and motivating banks to take more risks (Gan, 2004). Overall, based on the above discussion, how monetary policy influences bank risk-taking on both sides of the balance sheet is theoretically ambiguous and remains a significant empirical issue. The available empirical literature on the impacts of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity risk is somewhat limited. In particular, we are aware of a few studies that pay attention to such impacts. Using time-series data in the USA from 1980 to 2008 with multiple VAR strategies, Angeloni et al. (2015) document that monetary policy easing could cultivate bank risk-taking in the funding structure (captured by the proxies of non-core bank liabilities) and the asset side (measured by the soundness of bank borrowers). de Moraes et al. (2016) confirm the working of the bank risk-taking channel in Brazil in the sense that banks respond to monetary expansion by reducing the levels of capital adequacy ratio (CAR). An expanded version of this work performed by de Moraes and de Mendonça (2019) completes the prior Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 621 IJMF 17,4 622 research effort when indicating that lower interest rates make banks more leveraged. Exploring how monetary policy in European countries affects bank liquidity, Lucchetta (2007) provides some mixed results. The author finds that the investments in liquid assets are negatively linked with risk-free interest rates but positively with interbank interest rates. Peydro et al. (2017) investigate how banks in Italy construct their asset portfolio after monetary shocks. They reveal that banks tend to prefer security holdings to lending activities during monetary expansion, which is, however, captured by the central bank’s liquidity injection. Given the different approaches with conflicting results in the existing literature, our study is the first to simultaneously examine how bank leverage and liquidity react to monetary policy changes. 3. Relevant background of the Vietnamese banking industry and monetary policy Over the last decades, the banking industry has always occupied a dominant position in the Vietnamese financial system. It is generally considered as the key driver of economic growth. Recent remarkable reforms have changed and opened up the Vietnamese banking industry, especially after the country entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. This event led to increased participation of foreign banks in the banking market (Batten and Vo, 2016; Le, 2017). In this regard, additional reforms have been made to promote the efficiency and competitiveness of domestic banks. Despite multiple changes, large domestic banks still dominate the banking system (Stewart et al., 2016). Simultaneously, the segment of foreign banks is considerably small compared to domestic counterparts (Dang, 2019a). The credit boom during 2007–2009 in Vietnam has caused numerous financial consequences. Many banks suffered from heavy non-performing loan burdens and serious liquidity problems after this period. This situation led to intense interventions and tighter regulations by the SBV. Since 2010, the SBV announced the fundamental principles of international guidelines on banking supervision. Banks are thus required to build up their capital buffers to meet the minimum capital requirement. This generates considerable implications for banks in improving efficiency and restructuring funding to survive in an increasingly competitive environment. The SBV sets a framework of various monetary policy targets. There is no main target precisely defined in terms of controlling inflation, boosting economic growth and stabilizing the macroeconomic environment (Dang and Dang, 2020). With this setting, the SBV implements multiple monetary policy tools to fulfill its mandate, highlighting the unique characteristics of the Vietnamese monetary policy regime. In principle, the SBV can use traditional monetary tools, such as the reserve requirement and the base interest rate, to regulate the banking market. These used to be powerful tools to adjust credit supply and establish a limit for lending rates, particularly during the early operation periods of the SBV. However, the role of the reserve requirement and the base interest rate has diminished recently. As a result, these traditional tools remain fixed for a prolonged time. In practice, the SBV regularly alters policy rates and implements administrative controls to influence the interest rate framework. Regarding policy rates, the SBV has charged commercial banks by refinance rates (for short-term loans) and rediscount rates (for discounted valuable papers). Over the years, these policy rates were adjusted frequently to large extents. For administrative controls, the SBV imposes ceilings on deposit rates and floors on lending rates. The SBV introduced and removed these ceiling and floors on interest rates repeatedly. Additionally, open market operations are also a key tool for the SBV to pursue its monetary targets. Using this tool, the SBV could inject/withdraw liquidity directly into/from the financial market. Because of the distinction in nature, the influential mechanism of this tool on the banking market, compared to the interest-based tools, is not heterogeneous. Figure 1 displays the yearly average evolution of bank leverage, liquidity and monetary policy interest rates in the Vietnamese banking market over time. In general, bank leverage and liquidity positions progressed in two different directions. During 2007–2018, bank leverage posited an upward trend, while liquidity positions exhibited a downward momentum on average. At the same time, short-term lending rates and rediscount rates showed similar changes. After a period of alternating increases and decreases from 2007 to 2011, both interest rates began to decline continuously from 2011 to 2018. In sum, the movements tend to show an opposite path between interest rates and bank leverage. In contrast, most of the time, it is possible to recognize interest rates and bank liquidity following a similar path. Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 623 4. Methodology and data 4.1 Variables There has been no consensus on how to gauge monetary policy in the existing literature so far. Given this context and the relevant background of the monetary regime in Vietnam Bank leverage and rediscount rates 14.00 12.00 10.00 8.00 6.00 4.00 2.00 - 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Rediscount rates (%) Leverage Bank liquidity and lending rates 30.00 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 5.00 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Lending rates (%) Liquidity (%) Figure 1. Bank leverage, liquidity positions and monetary policy interest rates IJMF 17,4 624 (presented in Section 3), we use short-term lending rates, on average, in the market as the first monetary policy indicator. Changes in this indicator well capture the adjustments in monetary policy (e.g. Chen et al., 2017; Yang and Shao, 2016). Besides, we also consider two types of policy rates mentioned above, namely, refinance rates and rediscount rates, which may reasonably describe the monetary policy stance initiated by the SBV. Three indicators of monetary policy are valuable complements that reinforce our estimation’s robustness. In this regard, the general mechanism for these selected indicators is that a decrease in interest rates implies an expansionary monetary policy. We construct the measures of bank leverage and liquidity as follows. For bank leverage, we consider the ratio of total assets to equity capital, which is a traditional measure. Higher leverage implies that a bank depends more on liabilities rather than equity. Next, following standard practice, we simply define bank liquidity by the ratio of liquid assets to total assets, in which liquid assets include cash and interbank deposits. The higher the ratio is, the more liquid a bank is, or, alternatively speaking, the less liquidity risk a bank faces. Finally, we follow two strands of literature on the determinants of bank liquidity (or liquidity risk) and bank leverage (or capitalization) to incorporate key control variables. To this end, we include bank size (natural logarithm of total assets), bank return (return on average assets) and bank risk (loan loss provisions/gross loans) to account for differences in bank profiles. For the effect of bank size on bank leverage, larger banks may be more leveraged as they are better recognized by the market (Gropp and Heider, 2010). As to the impact of bank profits, theories show that more profitable banks could diminish the asymmetric information problem (Mankiw, 1986), which lowers the cost of issuing equity (Myers and Majluf, 1984). Hence, these banks may hold a larger capital buffer. Based on the trade-off theory, risky banks may prefer a low debt ratio to restrict overall risk exposures (Bradley et al., 1984). As commonly suggested in the literature, the “too big to fail” hypothesis explains the moral hazard and excessive risk-taking behavior of large banks (Dietrich et al., 2014). So, one could expect these banks to hold less liquid assets than smaller banks. According to the “search for yield” hypothesis, more profits may discourage banks from taking more risks by investing in illiquid and high-yield assets (Rajan, 2006). Regarding the impact of credit risk on bank liquidity, prior documents indicate that if bank asset portfolios deteriorate, depositors will quickly claim back their money (Diamond and Rajan, 2001). This situation displays a close correlation between credit risk and liquidity risk. We also include the macroeconomic factors, namely, the economic cycle (growth rate of GDP) and the inflation (annual inflation rate). These variables control the effect of the economy, which is time-variant but constant to banks. In economically prosperous periods, banks might enhance the capital level, thanks to better earning capacity (Shim, 2013), and gain more incentives to substitute their assets by loans due to the growing borrowing demand from the market (Dietrich et al., 2014). Besides, increased interest rates during inflationary periods are likely to influence bank behavior in terms of funding and investments (Adesina, 2019). 4.2 Sample data We employ the data of Vietnamese commercial banks for this study. For each bank, we hand collect the data from annual financial reports on its website from 2007 to 2018. We exclude banks that fail to publish at least five continuous audited financial reports. Our sample constitutes an unbalanced panel with 349 bank-year observations from 30 banks, covering about 90% of the banking system’s total assets in Vietnam. Policy rates are extracted from the SBV, whereas lending rates and other macro data are obtained from the International Financial Statistics. After building variables, we winsorize them at 2.5 and 97.5% to curtail the effects of extreme outliers. 4.3 Model specification and econometric method To investigate the impacts of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity, we specify a dynamic linear model specification as follows: Balance structurei;t ¼ α0 þ α1 3 Balance structurei;t–1 þ α2 3 MPt–1 þ α3 3 Banki;t–1 Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity þ α4 3 Macrot–1 þ ui;t (1) where the dependent variable is either bank liquidity or bank leverage of bank i in year t. MP denotes monetary policy indicators of main interest. Bank and Macro represent bank-level and macroeconomic controls, respectively, while ui;t is the idiosyncratic error. All variables are lagged by one period to mitigate the potential endogeneity bias and reflect that banks do not react to economic decisions immediately. By inserting a lagged dependent variable, we expect bank liquidity and bank leverage to be persistent over time since the balance sheet structure could not be modified promptly. The dynamic panel is subject to biased and inconsistent estimation if we regress it by least-squares methods. Therefore, we utilize the system generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator to solve the problems raised (Arellano and Bover, 1995; Blundell and Bond, 1998). This approach combines regression equations in differences and levels in a system, and applies the lagged values of regressors in levels and first differences as instruments. In this regard, the GMM estimator could deal with the lagged dependent variable, unobserved fixed effects, independent endogenous regressors, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation in the regression model. We follow Roodman (2009) to gain more efficient estimates by performing the two-step procedure and restricting the proliferation of instruments, which may cause the “too many instruments” problem. Finally, we need two diagnostic tests to justify the usage of the GMM estimator: (1) the Hansen test for over-identifying restrictions, which validates the appropriateness of instruments; (2) the Arellano–Bond test for the autocorrelation in residuals, in which we need to ensure the absence of the second-order autocorrelation. 5. Results and discussions After presenting the descriptive statistics, this section first presents the baseline estimates on the impacts of monetary policy on bank liquidity and leverage in Vietnam. Then, we further examine the heterogeneous effects across banks of different sizes. In the next subsection, we repeat our estimation with the NSFR rule under Basel III, which speaks to the stability of liabilities and liquidity of assets in a combined equation. This subsection is our outstanding innovation in this study. Finally, we check the sensitivity of our obtained results in additional different routes. 5.1 Descriptive statistics Table 1 outlines the descriptive statistics for our research sample. Bank liquidity ranging from 6.609% to 34.108% is distributed with a mean of 17.287% and a standard deviation of 9.120% points. This reveals a substantial variation in the levels of liquidity positions across banks. A similar pattern is noted for bank leverage as well, which ranges from 5.451 to 16.331, with an average value of 10.672 and a standard deviation of 3.481. Regarding monetary policy, we could realize sizable standard deviations and wide ranges of distribution for three indicators, thereby indicating the considerably fluctuated evolution of interest rates in Vietnam over time. We also report the correlation matrix in Table 2. All coefficients of independent variables are small, except for those between monetary policy indicators and the inflation rate. Hence, 625 IJMF 17,4 Variable Definition Monetary policy indicators i_lend Short-term lending rates i_refin Refinance rates by the SBV i_redis Rediscount rates by the SBV 626 Bank liquidity and leverage NSFR Net stable funding ratio under Basel III guidelines Liquidity Cash plus interbank deposits/total assets Leverage Total assets/equity Bank-level controls Return Return on average assets Size Natural logarithm of total assets Risk Loan loss provisions/gross loans Table 1. Summary statistics Mean S.D. Min Max p25 p75 10.660 8.226 6.066 3.367 2.582 2.718 6.960 6.250 3.500 16.954 15.000 13.000 7.117 6.500 4.500 13.471 10.000 7.000 120.839 13.388 99.653 140.834 109.605 132.068 17.287 9.120 6.609 34.108 9.630 24.187 10.672 3.481 5.451 16.331 7.933 14.961 0.800 13.859 1.254 0.505 0.477 0.455 0.108 13.162 0.723 1.655 14.603 2.189 0.388 13.411 0.890 1.209 14.245 1.525 Macroeconomic controls GDP Growth rate of GDP 6.186 0.602 5.398 7.076 5.421 6.679 Inflation Annual inflation rate 7.919 5.251 3.244 18.676 3.520 9.094 Note(s): The research sample covers the period from 2007 to 2018, with 349 bank-year observations from 30 Vietnamese commercial banks in the regression stage, we exclude the inflation variable from our models to avoid severe multicollinearity [3]. Another noteworthy preliminary result is excessively high correlation coefficients between three types of interest rates, which justify our choice of alternative monetary policy indicators. 5.2 Baseline estimation results In Table 3, we present our baseline estimation results. The Hansen test offers no evidence against the validity of the instruments, and the AR(2) test displays that there is no secondorder autocorrelation. These results ensure the consistency of the GMM estimator. Additionally, we also observe the significant persistence of the lagged dependent variables, justifying the use of a dynamic model. This result supports the notion that the structure of bank balance sheets possesses a part of the explanation in itself. In columns 1–3 (Table 3), the coefficients of monetary policy indicators are statistically significant with a negative sign. This result reveals that banks enlarge their financial leverage when interest rates drop. In columns 4–6 (Table 3), the coefficients on interest rates are positive and statistically significant in all regressions of bank liquidity. This finding supports the view that banks reduce the holdings of liquid assets in the event of monetary policy easing; in other words, they invest more in risky assets that expose them to higher liquidity risks. Our patterns are proved with three types of interest rates employed. Quantitatively, the magnitude of coefficients in columns 1–3 (Table 3) indicates that a decrease of one percentage point in interest rates would increase the leverage of banks by approximately 0.075–0.097 units, depending on the types of interest rates considered. Likewise, looking at columns 4–6 (Table 3), we could infer that a one percentage point decrease in interest rates would cause bank liquidity positions to drop by nearly 0.346– 0.582% points. These results highlight the economic plausibility our analysis, albeit the impact of monetary policy on bank leverage is quite small compared to that on bank liquidity. i_lend i_refin i_redis NSFR Liquidity Leverage Return Size Risk GDP Inflation i_refin 1.00 0.98 0.11 0.35 0.19 0.28 0.17 0.12 0.32 0.91 i_lend 1.00 0.91 0.88 0.06 0.46 0.27 0.36 0.29 0.08 0.39 0.95 1.00 0.10 0.32 0.17 0.24 0.15 0.10 0.29 0.92 i_redis 1.00 0.22 0.18 0.16 0.10 0.04 0.09 0.03 NSFR 1.00 0.22 0.39 0.38 0.27 0.06 0.46 Liquidity 1.00 0.31 0.74 0.21 0.20 0.24 Leverage 1.00 0.15 0.16 0.02 0.35 Return 1.00 0.43 0.15 0.28 Size 1.00 0.17 0.02 Risk Inflation 1.00 GDP 1.00 0.32 Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 627 Table 2. Correlation coefficients matrix IJMF 17,4 Lagged dependent variable 628 i_lend i_refin (1) Leverage (2) Leverage (3) Leverage (4) Liquidity (5) Liquidity (6) Liquidity 0.842*** 0.803*** 0.800*** 0.400*** 0.393*** 0.391*** (0.036) (0.037) (0.027) 0.346*** (0.061) (0.028) (0.027) (0.040) 0.097*** (0.024) 0.075*** (0.027) 0.542*** (0.069) 0.080*** 0.582*** (0.028) (0.072) Size 0.378 0.773*** 0.746*** 1.726*** 1.685*** 1.605*** (0.246) (0.205) (0.202) (0.508) (0.473) (0.467) Return 0.025 0.289*** 0.300*** 2.209*** 2.101*** 2.071*** (0.127) (0.094) (0.096) (0.532) (0.491) (0.505) Risk 0.205* 0.279** 0.274** 2.695*** 2.755*** 2.742*** (0.123) (0.116) (0.124) (0.331) (0.328) (0.322) GDP 0.349*** 0.298*** 0.270** 0.469* 0.908*** 1.145*** (0.082) (0.093) (0.106) (0.242) (0.282) (0.282) Observations 319 319 319 319 319 319 Banks 30 30 30 30 30 30 Instruments 26 26 26 26 26 26 AR(1) test 0.006 0.007 0.007 0.000 0.000 0.000 AR(2) test 0.488 0.502 0.525 0.987 0.814 0.920 Hansen test 0.127 0.174 0.157 0.128 0.129 0.123 Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the two-step system GMM estimator in the dynamic panel. The dependent variables are bank leverage (total assets/equity, columns 1–3) and bank liquidity (liquid assets/ total assets, columns 4–6). The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). Other controls are return/average assets (Return), the natural logarithm of total assets (Size), loan loss provisions/gross loans (Risk) and the growth rate of GDP (GDP). Diagnostic tests are displayed with p-values. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and *, ** and *** indicate significance levels at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively i_redis Table 3. Baseline results Overall, when the central bank eases monetary policy to stimulate the economy, banks respond by raising their leverage on the liability side and cutting liquidity positions on the asset side. Our consistent findings lend support to (1) the “search for yield” hypothesis which predicts banks have more incentives to invest in riskier segments and thus reduce the holdings of liquid assets as monetary policy is relaxed (Borio and Zhu, 2012; Rajan, 2006); and (2) the model developed by Dell’Ariccia et al. (2014) and Valencia (2014) which concludes that banks prioritize higher leverage due to the lower funding costs stemming from decreased interest rates. Moreover, these empirical patterns potentially accord with the theory of Dell’Ariccia et al. (2014) and Valencia (2014) that bank risks on the liability side initiate and magnify those on the asset side, given the risks shifting from banks to creditors and the bounded losses. 5.3 The asymmetric effects by bank size In this subsection, we further analyze the impacts of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity by taking into account the moderating role of bank size. To do this, we insert the interaction terms between monetary policy indicators and bank size into the baseline equation. Our concept here is that we anticipate some banks of different sizes to be more involved in monetary policy transmission than others, so their heterogeneous reactions after monetary policy shocks may offer more insights into the current topic. Our analysis is motivated by the fact that the banking sector in Vietnam is dominated by large banks (Batten and Vo, 2016; Le, 2017). Their dominant position is shown in various aspects, especially the market share of credit and deposits. Under intense competition, small banks signaled a deterioration in their credit quality recently (Dang, 2019b). Moreover, considering bank size as one of the critical indicators of the banks’ financial strength, prior authors claim that larger banks might easily govern loanable funds during monetary changes by raising alternative external funds with lower costs (Kashyap and Stein, 1995). Empirically testing this hypothesis, subsequent studies suggest that banks of different sizes react differently to monetary policy adjustments. More precisely, larger banks’ lending and risk-taking are less influenced by monetary shocks than smaller banks (e.g. Amidu and Wolfe, 2013; Kishan and Opiela, 2006; Olivero et al., 2011). Additionally, thanks to competitive advantages, large banks could experience higher marginal returns by restricting the entrance of competitors, thus reducing their incentives to “search for yield” even when interest rates drop (Koetter et al., 2012). Given these previous works revealing the heterogeneity in the bank channels, it is of importance to investigate whether and how the relationship between monetary policy and bank balance structures varies across banks of different sizes. By doing this, our strategy enriches the literature strand that highlights the role of bank characteristics in the transmission of monetary policy through the bank channels. Table 4 reports the results of the asymmetric effects in the augmented model. We note that the standalone effects of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity remained identical as previously. Turning to the results of main interest, we observe that the interaction terms enter most regressions negatively and significantly (in some detail, columns 2–3 in the function of leverage and columns 4–6 in the specification of liquidity). These results suggest that larger banks’ financial leverage is more responsive to monetary policy changes, while the potency of monetary policy transmission toward bank liquidity is strengthened at smaller banks. On the asset side, our result concurs with the vast prediction in the bank lending and risk-taking channels that smaller banks are more sensitive to monetary shocks (Koetter et al., 2012). In contrast, on the liability side, our finding challenges Kashyap and Stein’s (1995) argument that large banks confront limited impacts from changes in interest rates. Hence, the hypothesis on the lower costs of external financing at large banks needs to be further attested to Vietnamese banks, so we leave this respect for more thorough works in the future. Our findings are also economically significant. For instance, using column 2 in Table 4, we infer that a decrease of one percentage point in refinance rates leads larger banks (75 percentile) to build leverage by 0.004 (0.005 3 [14.245 – 13.411]) units more than smaller banks (25 percentile). In contrast, taking column 6 in Table 4, we expect that a decrease of one percentage point in rediscount rates causes smaller banks (25 percentile) to reduce liquidity positions by 0.023 (0.028 3 [14.245 – 13.411]) percentage points more than larger banks (75 percentile). 5.4 The analysis with the Basel III NSFR Our analysis of the link between monetary policy and bank balance structure for Vietnamese banks has two main patterns during monetary expansion: (1) banks increase their financial leverage, and (2) banks reduce their liquidity positions. Going a step further, we now integrate both sides of balance sheets into the NSFR rule under the Basel III Accord and ask how monetary policy induces an impact on bank funding liquidity. Studying this linkage is the key contribution of this paper. The NSFR is introduced to encourage banks to hold a stable funding profile to avoid the likelihood of eroding their liquidity positions. In other words, the NSFR compares the overall illiquidity of bank assets to the overall stability of bank funding sources, with a prudential balance between liquid and illiquid exposures at the benchmark of NSFR equaling to 100%. According to the Basel III guidelines, we determine the NSFR by the ratio of “available stable Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 629 IJMF 17,4 Lagged dependent variable 630 i_lend i_lend 3 Size i_refin i_refin 3 Size (1) Leverage (2) Leverage (3) Leverage (4) Liquidity (5) Liquidity (6) Liquidity 0.837*** 0.779*** 0.787*** 0.483*** 0.484*** 0.474*** (0.036) (0.036) (0.027) (0.028) (0.041) 0.102*** (0.034) 0.002 (0.002) 0.069** (0.032) 0.005*** (0.002) (0.031) 0.520*** (0.083) 0.035*** (0.008) 0.640*** (0.091) 0.045*** (0.006) 0.088*** 0.525*** (0.029) (0.077) i_redis 3 Size 0.003*** 0.028*** (0.001) (0.005) Size 0.390 0.897*** 0.824*** 1.207*** 1.171*** 1.346*** (0.257) (0.227) (0.223) (0.440) (0.337) (0.369) Return 0.002 0.277** 0.299** 2.635*** 2.598*** 2.457*** (0.136) (0.125) (0.118) (0.524) (0.487) (0.501) Risk 0.115 0.164 0.182 2.084*** 2.046*** 2.230*** (0.121) (0.114) (0.115) (0.311) (0.323) (0.316) GDP 0.329*** 0.299** 0.223* 1.203*** 1.484*** 1.273*** (0.121) (0.128) (0.128) (0.269) (0.262) (0.251) Observations 319 319 319 319 319 319 Banks 30 30 30 30 30 30 Instruments 27 27 27 27 27 27 AR(1) test 0.006 0.007 0.007 0.000 0.000 0.000 AR(2) test 0.455 0.459 0.467 0.359 0.892 0.753 Hansen test 0.152 0.170 0.183 0.171 0.156 0.142 Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the two-step system GMM estimator in the dynamic panel. The dependent variables are bank leverage (total assets/equity, columns 1–3) and bank liquidity (liquid assets/ total assets, columns 4–6). The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). Other controls are return/average assets (Return), the natural logarithm of total assets (Size), loan loss provisions/gross loans (Risk) and the growth rate of GDP (GDP). Diagnostic tests are displayed with p-values. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and *, ** and *** indicate significance levels at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively i_redis Table 4. The heterogeneity across banks of different sizes funding” (a sum of components on the liability and equity side, each component is weighted based on its stability) to “required stable funding” (a sum of components on the asset side, each component is weighted based on its illiquidity). Within the scope of this study, we consider a bank with a higher value of the NSFR to improve funding liquidity, based on the construction of the NSFR [4]. In this regard, banks could grow the NSFR in several ways, such as by holding more liquid assets with stable funding, increasing stable funding levels or substituting illiquid assets with liquid assets. This study predates the NFSR regulation’s implementation in Vietnam. Moreover, our available bank-level data from our sample do not afford all items required to compute the NSFR precisely as suggested by Basel III. So, we employ the approximation approach commonly used in the literature to generate the NSFR for Vietnamese banks (Dietrich et al., 2014; King, 2013). This approach is close in spirit to Basel III guidelines [5]. Table 5 shows the estimation results for the function of the NSFR. These results consistently suggest a negative and significant impact of monetary policy on the NSFR across three different types of interest rates, which means that banks improve their funding liquidity when interest rates decrease. In particular, a decrease of one percentage point in interest rates (columns 4–6) leads to a 0.413–0.584% points increase in the NSFR. Furthermore, the significantly positive coefficients of interaction terms reveal that the transmission is elevated at smaller banks. Lower interest rates reduce the liquidity of asset portfolios; in other words, it enhances bank illiquidity, the denominator of the NSFR. So, an increase in the NSFR can be attributed to the numerator’s overwhelming effect, which must ensure a superior increase in bank funding stability. In should be noted that our previous interpretations exhibit the minor impact of monetary policy on bank leverage as a whole, compared to the sizable effect on liquidity. Consequently, the starling result from regressions of the NSFR suggests that banks seem to rearrange their funding sources on the liability side toward a more stable structure when costs of financing decrease. This result concretizes the idea of Angeloni et al. (2015) on the reconstructed composition of bank liabilities during monetary shocks. In more detail, (1) NSFR Lagged dependent variable i_lend i_refin i_redis i_lend 3 Size i_refin 3 Size i_redis 3 Size 0.503*** (0.039) 0.081 (0.125) (2) NSFR (3) NSFR 0.438*** 0.451*** (0.039) (0.039) 0.543*** (0.166) (4) NSFR 0.534*** (0.040) 0.413*** (0.121) 0.500*** (0.149) (5) NSFR 631 (6) NSFR 0.511*** 0.502*** (0.039) (0.040) 0.584*** (0.152) Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 0.429*** (0.139) 0.053*** (0.011) 0.043*** (0.010) 0.027*** (0.009) Size 2.831* 3.544*** 3.660*** 2.215*** 2.896*** 2.856*** (1.465) (1.371) (1.394) (0.693) (0.843) (0.883) Return 0.197 0.517 0.384 1.060 0.591 0.373 (0.737) (0.710) (0.724) (0.778) (0.876) (0.812) Risk 3.313*** 3.539*** 3.615*** 2.342*** 2.974*** 3.256*** (0.936) (0.943) (0.931) (0.818) (0.818) (0.841) GDP 2.250*** 2.735*** 2.915*** 3.950*** 3.712*** 3.398*** (0.433) (0.428) (0.459) (0.624) (0.549) (0.552) Observations 319 319 319 319 319 319 Banks 30 30 30 30 30 30 Instruments 26 26 26 27 27 27 AR(1) test 0.001 0.002 0.002 0.000 0.002 0.001 AR(2) test 0.653 0.431 0.515 0.836 0.639 0.755 Hansen test 0.103 0.138 0.135 0.104 0.123 0.118 Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the two-step system GMM estimator in the dynamic panel. The dependent variable is the net stable funding ratio under Basel III. The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). Other controls are return/average assets (Return), the natural logarithm of total assets (Size), loan loss provisions/gross loans (Risk) and the growth rate of GDP (GDP). Diagnostic tests are displayed with p-values. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and * and *** indicate significance levels at 10% and 1%, respectively Table 5. Monetary policy and Basel III funding liquidity regulation IJMF 17,4 632 such funding restructure is more pronounced for smaller banks, which less prefer to rebalance the ratio between liabilities and equity as described in Subsection 5.3. While there is a handful of studies that examine the determinants of liquidity rules introduced by Basel III guidelines, this study makes the first attempt to shed light on the impact of monetary policy on the NSFR. In our context, it allows us to achieve a better understanding of how banks organize their stable funding sources and illiquid asset portfolios during monetary changes. 5.5 Robustness checks Though the usage of the system GMM estimator in the dynamic panel with multiple monetary policy indicators has yielded consistent results so far, we still desire to demonstrate further the robustness of our findings by some additional directions. To this end, we first employ alternative measures for bank leverage and liquidity. We continue to use liquid assets as a share of total assets to proxy bank liquidity, in which liquid assets expand to a combination of cash, interbank deposits and securities (Gambacorta and Mistrulli, 2004). In Vietnam, banks could simply liquidate their securities via the stock exchange or open market operations. Regarding bank leverage, we follow Beltrame et al. (2018) to define an adjusted measure by the ratio of total assets plus loan loss provisions to equity plus loan loss provisions. From the perspective of a financial intermediary, this measure could be considered as the sterilization of the loan loss provisions’ influences. After designing alternative dependent variables, we re-estimate the regressions with the two-step system GMM estimator and report the results in Table 6. Interestingly, our results remain consistent with the patterns obtained previously. Second, we change the model specification and thus apply alternative estimators. One could claim that bank balance sheets do not necessarily reflect a persistent nature over time. So, we perform our analysis in this part by the static model with fixed effects. The setting is supported by the Hausman test that suggests the preference of fixed effects over randomeffects models. We first regress our model with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors. In this respect, we conduct the correction procedure introduced by Hoechle (2007) to address the autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity and cross-sectional dependence issues. We also employ the IV method (which requires exact identification) given that our model specification may suffer from the endogeneity bias (due to potential simultaneity or omitted variables). To this end, we use the inflation variable as an instrument for monetary policy indicators as theories posit that the central bank establishes interest rates in response to inflation (Clarida et al., 1998). We then re-estimate all regressions of various alternative measures for both dependent and independent variables using models with fixed effects. Tables 7 and 8 exhibit the outcomes [6]. Though the significance levels of several regressions have diminished slightly, our main findings are still confirmed [7]. 6. Conclusions The study empirically examines the effects of monetary policy on bank leverage and liquidity. Based on a sample of Vietnamese commercial banks during 2007–2018, we document that banks become more leveraged and less liquid during monetary expansion. Further analysis reveals that the liquidity of smaller banks is more sensitive to the monetary policy changes, while the leverage of larger banks is more responsive to the monetary policy shocks. The former is in line with the vast majority of literature highlighting the strengthened potency of monetary policy transmission at smaller banks. However, the latter interestingly challenges the widely employed claim that larger banks are less affected by monetary shocks due to their copious substitute funding (Kashyap and Stein, 1995). (1) Leverage (alter) Lagged dependent variable i_lend i_lend 3 Size i_refin i_refin 3 Size 0.799*** (0.044) 0.118*** (0.028) 0.001 (0.001) (2) Leverage (alter) (3) Leverage (alter) 0.739*** 0.748*** (0.044) (0.043) 0.083*** (0.030) 0.006*** (0.001) (4) Liquidity (alter) 0.629*** (0.039) 0.478*** (0.093) 0.044*** (0.006) (5) Liquidity (alter) (6) Liquidity (alter) 0.619*** 0.613*** (0.057) (0.060) Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 633 0.529*** (0.111) 0.044*** (0.007) 0.098*** 0.434*** (0.026) (0.090) i_redis 3 Size 0.004*** 0.030*** (0.001) (0.007) Controls Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Observations 319 319 319 319 319 319 Instruments 27 27 27 27 27 27 AR(1) test 0.014 0.014 0.015 0.000 0.000 0.000 AR(2) test 0.447 0.411 0.423 0.258 0.403 0.386 Hansen test 0.166 0.139 0.162 0.317 0.154 0.163 Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the two-step system GMM estimator in the dynamic panel. The dependent variables are bank leverage ([total assets þ loan loss provisions]/[equity þ loan loss provisions], columns 1–3) and bank liquidity ([cash þ interbank deposits þ securities]/total assets, columns 4–6). The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). All control variables are included. Diagnostic tests are displayed with p-values. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and *** indicates significance levels at 1% i_redis Additionally, as an innovation in this study, we examine how monetary policy drives the NSFR rule under Basel III, which is introduced to maintain the stability of funding and the liquidity of assets. The result suggests that lower interest rates encourage Vietnamese banks to improve the NSFR, and this impact is more pronounced at smaller banks. Amid monetary policy easing, banks appear to modify the composition of liabilities to improve the stability of funding sources. Our findings are strongly confirmed by a battery of robustness checks, using two econometric models of static and dynamic panels, multiple monetary policy indicators and alternative measures of bank liquidity and leverage. Our findings provide insightful implications for monetary authorities, particularly in emerging countries. First, the significant response of banks to monetary policy stance may give monetary authorities the confidence to rely on their current tools to regulate the market. Second, the indications of bank risk-taking behavior should be carefully considered when central banks initiate monetary policy. More concretely, when monetary policy is softer, the bright side is that banks tend to shift their funding sources into more stable ones, whereas the dark side is that it provides banks with incentives to utilize more financial leverage and maintain lower liquidity positions. Third, the adverse effects of monetary policy easing on bank risk-taking can be alleviated or elevated according to different groups of bank sizes. Additionally, from the standpoint of research implication, our work opens an avenue for future investigation on the impact of monetary policy on Basel regulations. Table 6. Alternative measures for bank leverage and liquidity Table 7. Robustness checks with static models Yes 319 0.344 Yes 319 0.345 0.158** (0.079) 0.006 (0.005) 0.145** (0.067) 0.006 (0.004) Yes 319 0.344 (3) Leverage Yes 319 0.204 239.773*** 1383.299*** 2312.407*** 0.275*** (0.071) 0.004 (0.004) (5) Leverage (alter) Yes 319 0.244 257.389*** 0.163*** (0.060) 0.007* (0.004) (4) Leverage (alter) 2282.061*** 0.258*** (0.064) 0.006 (0.004) Yes 319 0.209 257.015*** (6) Leverage (alter) Yes 319 0.475 0.782*** (0.155) 0.007 (0.010) (7) Liquidity Yes 319 0.483 0.975*** (0.168) 0.015 (0.010) (8) Liquidity 0.883*** (0.159) 0.001 (0.009) Yes 319 0.478 (9) Liquidity 1969.085*** Yes 319 0.264 252.684*** 0.790*** (0.186) 0.028** (0.012) (10) Liquidity (alter) 1368.554*** Yes 319 0.281 239.479*** 0.837*** (0.206) 0.029** (0.012) (11) Liquidity (alter) 2462.750*** 0.739*** (0.188) 0.014 (0.010) Yes 319 0.275 259.213*** (12) Liquidity (alter) Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the fixed effects static panel, regressed with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors (columns 1–3 and columns 7–9) and the IV approach (columns 4–6 and columns 10–12). The dependent variables are bank leverage (two alternative measures, columns 1–6) and bank liquidity (two alternative measures, columns 7–12). The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). All control variables are included. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and *, ** and *** indicate significance levels at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively. The results from the tests for the IV approach indicate that our instruments are neither under-identified nor weak Controls Observations R-squared Underidentification test Weak identification test i_redis 3 Size i_redis i_refin 3 Size i_refin i_lend 3 Size 0.191** (0.090) 0.003 (0.004) (2) Leverage 634 i_lend (1) Leverage IJMF 17,4 Yes 319 0.117 0.005 (0.015) Yes 319 0.109 0.986*** (0.260) (6) NSFR 0.839*** (0.293) (8) NSFR 0.778*** (0.272) (9) NSFR 0.033** (0.017) 0.854*** (0.267) (10) NSFR 0.017 (0.017) 0.864*** (0.299) (11) NSFR 0.779*** (0.272) (12) NSFR 0.005 (0.015) Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 319 319 319 319 319 319 0.095 0.110 0.107 0.110 0.114 0.107 252.768*** 231.377*** 259.038*** 252.684*** 239.479*** 259.213*** 1981.318*** 1140.371*** 2455.329*** 1969.085*** 1368.554*** 2462.750*** 0.681*** (0.240) (7) NSFR Note(s): The regression results are obtained using the fixed effects static panel, regressed with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors (columns 1–6) and the IV approach (columns 7–12). The dependent variable is the net stable funding ratio under Basel III. The explanatory variables of interest are monetary policy indicators, including lending rates (i_lend), refinance rates (i_refin) and rediscount rates (i_redis). All control variables are included. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and ** and *** indicate significance levels at 5% and 1%, respectively. The results from the tests for the IV approach indicate that our instruments are neither under-identified nor weak Yes 319 0.109 Yes 319 0.110 i_redis 3 Size Controls Observations R-squared Under-identification test Weak identification test 1.128*** (0.274) (5) NSFR 0.022 (0.017) 0.982*** (0.259) 0.960*** (0.252) (4) NSFR i_refin 3 Size Yes 319 0.112 1.033*** (0.264) (3) NSFR 0.036** (0.017) Yes 319 0.096 0.711*** (0.226) (2) NSFR i_lend 3 Size i_redis i_refin i_lend (1) NSFR Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 635 Table 8. Robustness checks for the NSFR with static models IJMF 17,4 Notes 1. See Chen et al. (2017) for more explanation of the different monetary policy background in advanced and emerging countries. 2. We use monetary policy easing for illustration hereinafter. 3. We further check the variance inflation factor (VIF) to ensure this treatment. 636 4. Drehmann and Nikolaou (2013) define funding liquidity as banks’ ability to immediately settle their obligations. The authors admit that this definition is partially equivalent to the view of Basel Accords. 5. For detailed information on the weights of items on- and off-balance sheets to calculate the NSFR, see Dietrich et al. (2014, p. 16). 6. To save space, we do not report all regressions we have. The remaining results indicate the identical patterns and are available upon request. 7. The statistical insignificance of the interaction terms (columns 1–6 in Table 7) yields evidence that bank size cannot modify how monetary policy drives bank leverage as substantially as the way monetary policy alters bank liquidity. References Acharya, V. and Naqvi, H. (2012), “The seeds of a crisis: a theory of bank liquidity and risk taking over the business cycle”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 106 No. 2, pp. 349-366. Adesina, K.S. (2019), “Basel III liquidity rules: the implications for bank lending growth in Africa”, Economic Systems, Vol. 43 No. 2, doi: 10.1016/j.ecosys.2018.10.002. Adrian, T. and Shin, H.S. (2010), “The changing nature of financial intermediation and the financial crisis of 2007–2009”, Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 603-618. Altunbas, Y., Gambacorta, L. and Marques-Ibanez, D. (2014), “Does monetary policy affect bank risk?”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 95-135. Amidu, M. and Wolfe, S. (2013), “Does bank competition and diversification lead to greater stability? Evidence from emerging markets”, Review of Development Finance, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 152-166. Angeloni, I., Faia, E. and Lo Duca, M. (2015), “Monetary policy and risk taking”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 52, pp. 285-307. Arellano, M. and Bover, O. (1995), “Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of errorcomponents models”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 29-51. Batten, J.A. and Vo, X.V. (2016), “Bank risk shifting and diversification in an emerging market”, Risk Management, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 217-235. Beltrame, F., Previtali, D. and Sclip, A. (2018), “Systematic risk and banks leverage: the role of asset quality”, Finance Research Letters, Vol. 27, pp. 113-117. Blundell, R. and Bond, S. (1998), “Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 87 No. 1, pp. 115-143. Borio, C. and Zhu, H. (2012), “Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism?”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 236-251. Bradley, M., Jarrell, G.A. and Kim, E.H. (1984), “On the existence of an optimal capital structure: theory and evidence”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 39 No. 3, pp. 1421-1460. Chen, M., Wu, J., Jeon, B.N. and Wang, R. (2017), “Monetary policy and bank risk-taking: evidence from emerging economies”, Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 31, pp. 116-140. Clarida, R., Galı, J. and Gertler, M. (1998), “Monetary policy rules in practice some international evidence”, European Economic Review, Vol. 42 No. 6, pp. 1033-1067. Dang, V.D. (2019a), “The risk-return trade-off of liquidity positions: evidence from Vietnamese banking system”, International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance, Vol. 12 No. 5, pp. 390-406. Dang, V.D. (2019b), “The effects of loan growth on bank performance: evidence from Vietnam”, Management Science Letters, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 899-910. Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity Dang, V.D. and Dang, V.C. (2020), “The conditioning role of performance on the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy: evidence from a multiple-tool regime”, Research in International Business and Finance, Vol. 54, doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101301. 637 de Moraes, C.O. and de Mendonça, H.F. (2019), “Bank’s risk measures and monetary policy: evidence from a large emerging economy”, North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 49, pp. 121-132. de Moraes, C.O., Montes, G.C. and Antunes, J.A.P. (2016), “How does capital regulation react to monetary policy? New evidence on the risk-taking channel”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 56, pp. 177-186. Delis, M.D. and Kouretas, G.P. (2011), “Interest rates and bank risk-taking”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 35 No. 4, pp. 840-855. Dell’Ariccia, G., Laeven, L. and Marquez, R. (2014), “Real interest rates, leverage, and bank risktaking”, Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 149 No. 1, pp. 65-99. Diamond, D.W. and Rajan, R.G. (2001), “Liquidity risk, liquidity creation, and financial fragility: a theory of banking”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 109 No. 2, pp. 287-327. Diamond, D.W. and Rajan, R.G. (2005), “Liquidity shortages and banking crises”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 60 No. 2, pp. 615-647. Diamond, D.W. and Rajan, R.G. (2006), “Money in a theory of banking”, American Economic Review, Vol. 96 No. 1, pp. 30-53. Diamond, D.W. and Rajan, R.G. (2012), “Illiquid banks, financial stability, and interest rate policy”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 120 No. 3, pp. 552-591. Dietrich, A., Hess, K. and Wanzenried, G. (2014), “The good and bad news about the new liquidity rules of Basel III in Western European countries”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 13-25. Drehmann, M. and Nikolaou, K. (2013), “Funding liquidity risk: definition and measurement”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 37 No. 7, pp. 2173-2182. Gambacorta, L. and Marques-Ibanez, D. (2011), “The bank lending channel: lessons from the crisis”, Economic Policy, Vol. 26 No. 66, pp. 135-182. Gambacorta, L. and Mistrulli, P.E. (2004), “Does bank capital affect lending behavior?”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 436-457. Gan, J. (2004), “Banking market structure and financial stability: evidence from the Texas real estate crisis in the 1980s”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 73 No. 3, pp. 567-601. Giordana, G.A. and Schumacher, I. (2013), “Bank liquidity risk and monetary policy. Empirical evidence on the impact of Basel III liquidity standards”, International Review of Applied Economics, Vol. 27 No. 5, pp. 633-655. Gropp, R. and Heider, F. (2010), “The determinants of bank capital structure”, Review of Finance, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 587-622. Hoechle, D. (2007), “Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence”, Stata Journal, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 281-312. Jimenez, G., Ongena, S., Peydro, J. and Saurina, J. (2014), “Hazardous times for monetary policy: what do twenty-three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit risktaking?”, Econometrica, Vol. 82 No. 2, pp. 463-505. The Econometric Society. IJMF 17,4 Kane, E.J. (1989), “The S&L insurance mess: how did it happen?”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 44 No. 5, pp. 1444-1448. Kashyap, A.K. and Stein, J.C. (1995), “The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets”, in Carnegie-Rochester Confer. Series on Public Policy, Vol. 42 No. C, pp. 151-195. Kashyap, A.K. and Stein, J.C. (2000), “What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy?”, American Economic Review, Vol. 90 No. 3, pp. 407-428. 638 Khan, H.H., Ahmed, R.B. and Gee, C.S. (2016), “Bank competition and monetary policy transmission through the bank lending channel: evidence from ASEAN”, International Review of Economics and Finance, Vol. 44, pp. 19-39. King, M.R. (2013), “The Basel III net stable funding ratio and bank net interest margins”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 37 No. 11, pp. 4144-4156. Kishan, R.P. and Opiela, T.P. (2006), “Bank capital and loan asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 259-285. Koetter, M., Kolari, J.W. and Spierdijk, L. (2012), “Enjoying the quiet life under deregulation? Evidence from adjusted lerner indices for U.S. banks”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 94 No. 2, pp. 462-480. Le, T.D.Q. (2017), “The interrelationship between net interest margin and non-interest income: evidence from Vietnam”, International Journal of Managerial Finance, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 521-540. Lucchetta, M. (2007), “What do data say about monetary policy, bank liquidity and bank risk taking?”, Economic Notes, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 189-203. Maddaloni, A. and Peydro, J.L. (2011), “Bank risk-taking, securitization, supervision, and low interest rates: evidence from the Euro-area and the U.S. lending standards”, Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 24 No. 6, pp. 2121-2165. Mankiw, N.G. (1986), “The allocation of credit and financial collapse”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 101 No. 3, pp. 455-470, Oxford University Press (OUP). Myers, S.C. and Majluf, N.S. (1984), “Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 187-221. Olivero, M.P., Li, Y. and Jeon, B.N. (2011), “Consolidation in banking and the lending channel of monetary transmission: evidence from Asia and Latin America”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 1034-1054. Peydro, J.-L., Polo, A. and Sette, E. (2017), “Monetary policy at work: security and credit application registers evidence”, SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2958917. Rajan, R.G. (2006), “Has finance made the world riskier?”, European Financial Management, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 499-533. Roodman, D. (2009), “How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata”, Stata Journal, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 86-136. Shim, J. (2013), “Bank capital buffer and portfolio risk: the influence of business cycle and revenue diversification”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 37 No. 3, pp. 761-772. Smith, B.D. (2002), “Monetary policy, banking crises, and the Friedman rule”, American Economic Review, Vol. 92 No. 2, pp. 128-134. Stewart, C., Matousek, R. and Nguyen, T.N. (2016), “Efficiency in the Vietnamese banking system: a DEA double bootstrap approach”, Research in International Business and Finance, Vol. 36, pp. 96-111. Taylor, J.B. (2011), “The financial crisis and the policy responses: an empirical analysis of what went wrong”, SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1341170. Valencia, F. (2014), “Monetary policy, bank leverage, and financial stability”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 47, pp. 20-38. Yang, J. and Shao, H. (2016), “Impact of bank competition on the bank lending channel of monetary transmission: evidence from China”, International Review of Economics and Finance, Vol. 43, pp. 468-481. Corresponding author Van Dan Dang can be contacted at: dandv@buh.edu.vn For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Monetary policy, bank leverage and liquidity 639