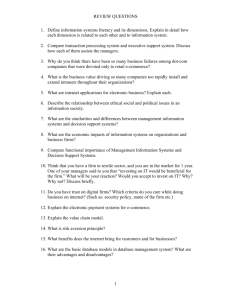

Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm

advertisement