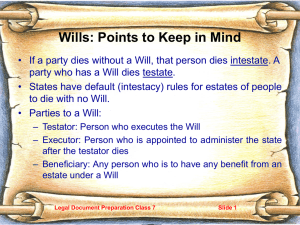

PROBATE & SUCCESSION – MR CHIMUKA Lecture 1 (30.10.17) “We are going to be talking about dead people” LOL Recommendation: After taking notes, look at the specific references of the law Sometimes the notes will point in a different direction of the law but neither of them is wrong. Exam will be based only on what is covered in the notes. INTRODUCTION This work is concerned with what happens to the property and problems left by a deceased person. The deceased will no longer need or be able to use or attend to them. For help and guidance, we shall look to the law, primarily the Intestate Succession Act of 1989 which is Chapter 59 of our laws and the Wills and Administration of Testate Estates Act of 1989 which is Chapter 60 of our Laws (“The Wills Act”). We shall also look at other relevant legislation and the interpretation of any such law by the Courts. When a person dies, leaving vested in him property of any kind, it is necessary for someone to assume control over which use that property to resolve whatever problems that may have been left by the deceased and to distribute any surplus to those who may be connected to the deceased or who may be entitled thereto. Section 19(1) of the Intestate Succession Act and section 45(1) of the Wills Act. The property left by a deceased person is called “his assets,” and the problems left by a deceased person are called “his liabilities.” The assets and liabilities of a dead person are called “his estate” sec 3 of the ISA and sec 3 of the WA. All the real and personal property of the deceased whether legal or equitable which he can dispose of during his lifetime or to the extent of his beneficial interest therein, are assets available for the resolution of his problems or the payment of his debts and liabilities. Anything which the deceased could have disposed of in his lifetime is his asset for this purpose. Sometimes a deceased person would leave complete instructions as to how his estate is to be dealt with upon his death and sometimes such instructions would be incomplete and at other times a person just dies without leaving Page 1 of 105 any instructions at all. Whether or not there are instructions, complete or otherwise, it is always necessary for someone to assume control over the estate of a deceased person and as already mentioned, to resolve any problems that may have been left behind using the assets of the deceased and to distribute any surplus to those that may be entitled. The person who assumes such control is called “the personal representative” of the deceased [Section 3 of the WA]. He somehow represents the deceased but because such person has died, what is left are his assets and liabilities, and the PR is therefore said to represent the estate rather than the deceased. All the assets and liabilities of the deceased vest in the PR as soon as he becomes one [Sec 24 of the ISA and sec 35 of the WA]. The deceased’s life is by way of speaking, prolonged through this person until all the problems or liabilities of the deceased are properly resolved and any asset left finds a new owner or as the case may be. When the deceased leaves instructions, the PR merely follows those instructions. But when the deceased leaves no instructions, the PR or leaves incomplete or invalid instructions, then the law comes in to provide guidance on who may be a PR in relation to the person who has died and on how such PR will proceed in handling the estate of the deceased or the property of the deceased which is not covered by valid instructions. THE PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE There are two types of PR: • One who is identified by the deceased when that person leaves instructions, called “an executor” if male, or “executrix” if female [sec 3 of the WA]. • One who is identified through the guidance of the law when the deceased has identified no one, particularly when he leaves no instructions [sec 15(1) and (2) of the ISA] or when the one chosen by the deceased is for some reason unable to take up the responsibility [sec 36(1) of the WA]. This person is called “an administrator” if male, or “an administratrix” if female [sec 3 of the ISA or sec 3 of the WA]. Page 2 of 105 The Executor This is the person who by express or implied appointment in some instructions left by the deceased is entrusted to administer the deceased’s estate [sec 3 of the WA]. He is the only PR who can obtain what is called a grant of probate [sec 29(1) of the WA], but he must be mentioned somehow in the instructions left by the deceased or the instructions must provide the means of identifying him positively [sec 29(2) of the WA]. No one else will be recognised by a court as PR if this person is available [sec 36(2) of the WA]. The Administrator There are two main types of administrator. Both are identified through or by the guidance of the law. • The one type comes in when there are valid instructions left by the deceased, but no one is able or willing to come forward and carry out those instructions. The law will provide guidelines on who or how an administrator can be identified or ascertained, and that law is sec 36(1) of the WA. When someone has been identified, through the guidance of the law, he must be appointed by a court [sec 3 of the WA]. After he has been appointed by the court (the probate court usually a division of the High Court), he becomes an administrator, but because the deceased had left instructions this person will be expected to carry out those instructions which will be attached to the order of the court making him an administrator. He is then called “an administrator with the instructions annexed” ie an Administrator Cum Testamento Annexo. • The other type of administrator comes in when there are no instructions at all [sec 3 of the ISA]. The law will provide guidelines as to who may become or be made administrator in respect of the estate of a person who dies leaving no instructions [sec 15(1) and (2) of the ISA]. When he has been identified through the guidance of this Page 3 of 105 law, he must apply to a court to be appointed or to be made administrator. After he has been appointed by the court, (which can be any court with probate jurisdiction) he becomes simply an administrator [sec 3 of the ISA]. There are other and special administrators who become necessary when there is a particular problem which requires to be attended to such as: • when there is a lis pendens (an issue actually pending in Court). When a court appoints someone to take care of the assets and liabilities of the deceased pending the resolution of the dispute between the people who are supposed to administer the estate he becomes “an Administrator pendete lite” [sec 18 of the ISA or sec 40 of the WA]. • There are times when assets of the deceased come in danger of going to waste before the correct PR is ascertained. In such a situation, a Court will appoint a person to take care of those assets by collecting, gathering or receiving them. This one when appointed becomes an “Administrator ad Colligenda Bona’’ [s37 of the ISA or sec 60 of the WA]. These two are only part of what are called limited grants which we shall see later. Probate or Testamentary Succession In this part of our subject, we shall look at the situation where the deceased left complete instructions, valid at law, as to how he wished his estate dealt with or handled after his death. The instructions valid in law are called “A Will’’. The Will is really a declaration of what a person wishes to happen concerning his estate when he is no longer able to make decisions for himself because he has died. In Latin, a declaration is called ‘’a testamentum’’. A declaration as mentioned above by someone planning to die is sometimes called a Testamentum or ‘’Testament’’. The person making the Testament is called a Testator or Testatrix if female [sec 3 of the WA]. When that person dies, they are said to have died ‘’testate’’ because they Page 4 of 105 have left a Testament. In the Will, the Testator will name or identify some person/s either expressly or by implication as the person(s) identified to handle his estate [sec 44 of the WA]. This is the person that we have learnt to be the Executor/Executrix. He or they, execute the Will; that is, carry out the instructions contained in it. When a Testator leaves a Will and in the Will he appoints or identifies some person or persons, either expressly or by implication to be the Executor(s), the estate of that Testator immediately vests in that Executor(s) as soon as the Testator dies [sec 35 of the WA]. The Executor therefore, becomes a PR automatically as soon as the Testator dies and can begin to carry-out the instructions contained in the Will [sec 3 of the WA]. However, it is possible that a Will may not be valid according to the law for several reasons, or that the person appointed Executor is not fit to execute that office [sec 29(2) of the WA], or some other problem may arise regarding anything or any part of the Will or estate. It may therefore be difficult for the Executor to convince a Bank or indeed, any other person who may have had dealings with the Testator that he is the Executor or that the Will is that of the Testator even when he could walk about with a copy of the Will. A Bank or indeed any other person, who might have had dealings with the deceased, will want to protect itself or himself that the person, claiming to be the Executor, is indeed what he claims to be, and the Will is indeed what it is. The Executor will therefore need to provide some proof that: • he is the person chosen by the deceased to be the Executor and • that the Will is indeed the valid Will of the Testator. [s35 of the WA]. An Executor can, however, commence legal proceedings as soon as he becomes a PR when a Testator dies but he cannot secure judgment because at this stage he will require to provide evidence of his authority. He can do anything until the need to provide proof of his office as Executor becomes necessary. It sometimes happens that the deceased left a valid Will but failed to appoint a person, or may appoint a person to execute his Will but such person either dies before the Testator or for some other reason is unable to take up the position of Executor. The person who will be identified to administer such dead person’s estate as we have seen Page 5 of 105 above, will still have to prove that the Will is valid, it is that of the Testator, and he has the right to take up the job of Administrator [sec 36(1) WA]. He cannot become an Administrator without proving to a Court first that the Will is valid, and secondly, that he has the right to be one [sec 36(1)]. Probate or testamentary succession is therefore the process by which, after production of some proof relating to a Will, the estate of a testator is properly dealt with after he has died. Intestacy or Intestate Succession In this part of our subject we shall look at: • A situation where the deceased person left no Will at all [sec 4(1) ISA]; or • No Will relating to a particular property or asset [sec 4(2) ISA]; or • The Will is incomplete or invalid in respect of certain of his assets [sec 3 ISA]. In this situation he is said to have died Intestate because he leaves no testament or partially intestate because he leaves an incomplete or partial testament. When this happens, the law provides guidelines on what should happen on the basis of what a reasonable person could have done in the circumstances. It will provide guidelines on which person can become a PR [sec 15(1) (2) ISA] and how many can become such representatives at any time or in particular situations [sec 16(1) (2) ISA]. A person identified in this manner will become an Administrator only when a Court (any Court with probate jurisdiction, i.e. Local or High Court) has actually granted a document authorizing him to become one [sec 3 ISA]. The Court is any Court: it can be the Local Court or a Higher Court, as long as it has probate jurisdiction [sec 15(1) read with sec 3 ISA or sec 36(1) of the Local Courts Act]. Section 15(1) reads, “the court may on the application of any interested person grant letters of administration to that interested person” while section 3 defines Court as “the High Court, subordinate court or a local court.” There is a school of thought to the effect that, a local court has no power to appoint an Administrator if the value of the Estate to be dealt with exceeds KR50. This is because Page 6 of 105 sec 43(2) of the ISA states “A local court shall have and may exercise jurisdiction in matters relating to succession if the value does not exceed K50.’’ However, it would appear that a proper reading of the statute will show that Sec 43(2) of the ISA should not contrary to some decided cases, apply to the creation or appointment of a PR but rather to the determination or resolution of matters, or problems arising from the Administration of an estate. At the time of the appointment of an Administrator, the Court is not concerned with how the estate will be dealt with, but rather, who will deal with the estate. If a situation arises where a Court is required to decide on a matter of who is entitled to what asset or even who is entitled to do what, in relation to an estate, at this stage, it will be necessary for the Court to have the necessary qualification, that is to say, the Court must at this stage, have the proper jurisdiction [sec 15(2) ISA]. But, see the case of Oparaocha v Murambirwa 2004 ZLR 141. While the ruling of the Supreme Court in the case above, is the official interpretation of the Law now until it is overruled, or reviewed, a reading of the case suggests that the Court may have been misled or it may have misdirected itself in the manner suggested above. The powers of an Administrator are said to arise from the date of appointment by a Court or the date of the grant unlike an Executor whose powers start when the Will becomes effective on the death of a Testator [sec 3 of the ISA or a similar section in the WA]. The document issued by the Court is called an “Order of Appointment of Administrator” or “Letters of Administration” although the Administrator only gets his powers after a grant. When made, a grant operates retrospectively from the date of death [sec 24(1) of the ISA]. All the property and liabilities of the deceased immediately vest in the Administrator as soon as he becomes such Administrator, that is to say, as soon as a grant is made or as soon as a court appoints him. The grant although retrospective will not legalize, or correct mistakes committed between the date of death and the date of the grant [Sect. 24(1)]. If a person performs any of the duties of a personal representative when he is not a named Executor in a Will or where there is no Will before a grant of letters of administration is made to him, that person becomes an “Intermeddler” [Section 6 Page 7 of 105 Administrator General Act or Section 65 Wills Act]. He has intermeddled in the estate of the deceased and is also called an “Executor De Son Tort”. He is personally liable to the estate to the value of the assets which came into his hands or for which he had control, but his lawful actions bind the estate [sec 6(2) of the AGA]. Intestacy or intestate succession is therefore the process by which after a grant of letters of administration, the estate of an intestate is properly dealt with after he has died. PART ONE: GRANTS OF REPRESENTATION How to Apply for a Grant The first requirement of a person identified to be a personal representative is that he must know where the deceased was domiciled at the date of his death and in some cases, it may also be necessary to know where he was domiciled at the date of making his Will, where the deceased left a Will. The law of a person’s domicile at execution of a Will might determine its validity, he’s domicile at death might determine how his estate is to be administered. This is necessary because the administration or the treatment of the deceased’s personal or movable estate depends on lex domicilii, that is, the law of the country of his domicile. The immovable estate of a deceased person is however, treated according to lex situs, that is, the law of the country where the asset is situate. The country of domicile is that which a person considers to be his home. The second requirement of such person is to know all the assets and liabilities of the deceased wherever these may be in the world. It may be possible that some asset or liability of the deceased, may not be known to members of the deceased’s family or the person identified to be personal representative. In order to overcome this, and to give an opportunity to anyone who may have objections, whether a member of the deceased’s family, or otherwise and even a creditor of the deceased, either relating to the Will itself where the is a Will, or the person identified whether there is a Will or not, it is important and prudent for such person to advertise in this country his intention to go to court to obtain a grant of representation. The advertisement should be in any daily newspaper preferably over a minimum of two consecutive days and Page 8 of 105 once in the Government Gazette. The advertisement must ask the persons with any interest in the estate of the deceased resident in Zambia for information regarding any asset or liability of the deceased that they may be aware of. Those assets that require to be valued must be valued. The balances in the bank must be ascertained. Assurance policies on the life of the deceased located and the values thereof, ascertained. The third requirement of a person identified to be personal representative is to make an oath in an affidavit in which he will establish his right to a grant of representation or it is in this document that he explains to the court how or why he qualifies to be a personal representative. The affidavit being a very important document must be prepared with the greatest of care as any mistake may compel the court to refuse to make a grant until the mistake has been rectified. The Three Basic Grants • A Grant of Probate The Will is an indication of what it contains and not proof of what it is. In order to provide acceptable evidence of his title as Executor, it is necessary to prove that a Will is indeed a Will of the deceased and to prove that the Will is valid in the eyes of the Law, and to prove that the Executor is indeed the person named or identified in that Will and to prove that he qualifies to hold that office [sec 35 of the WA]. This is done by taking the Will to the court and asking the court to study the Will to see whether it complies with the legal requirements for proving all the matters mentioned above. This is done by the Executor and normally through his lawyer as the court does not trust anyone. Any statement or request made to it, must be made on oath in an affidavit. In the affidavit known as the “Executor’s oath”, the Executor must: i. State his true and proper names as well as his address and occupation. If a different name was used by the Testator in the Will, such as a nick name, or an uncommonly known name, this must be stated in the Affidavit. ii. Identifying the Will, or whatever other testamentary documents which requires to be proved, or which he is trying to prove. The identification is completed by “Marking” the Will or any other testamentary document. The “marking” consists of Page 9 of 105 the Executor and the Commissioner for Oaths or the person before whom the Oath is being taken, signing on top of that original Will or document. iii. Give the full name and address of the Testator. The true and proper names must always be given and if another name was used, in the Will, this must be explained in the oath or in a separate affidavit. iv. Give the date of death as it appears on the death certificate although the certificate itself need not be produced unless it is requested for by the court. v. Give the place of death as well as the domicile of the Testator at the date of death. It is sometimes necessary to state the Testator’s domicile at the date of making the Will if it is different from the domicile at death, as certain rules of construction may require some parts of the Will to be construed according to the law of domicile when the Will was made. Supposing at the time he made the Will he was domiciled in Zambia and then decided to go and die domiciled in South Africa. They are reading the Will there and it says "I give 50 pin to my father" he would be given drawing pins LOL. vi. Swear that the Executor is the named Executor and if he is the only named Executor in the Will, this must be stated. vii. Swear that he will correct and get in the real and personal estate of the deceased and administer it according to the law. viii. Swear that he will, when required by the court, exhibit on oath in the court, a full inventory of such estate and when so required, render an account of the administration of such estate to the court [sec 45(1)(c) of the WA]. ix. Swear that when required, to do so by the High Court he will deliver up the grant of probate to that court. x. State the gross value of the estate to be administered as shown in the declaration of the estate mentioned above. Only the Executor named in the Will can apply for a grant of probate [sec 29(1) of the WA], and only up to a maximum of 4 Executors can be granted probate at the same Page 10 of 105 time in respect of the same estate [sec 30(1) of the WA]. As the Executor is chosen, or identified by the Testator, because of the trust the Testator has in him, it is not necessary for the Executor to give any assurance to anyone of how well he will perform his functions as personal representative. He is therefore, not normally required to provide any security for the due administration of an estate [sec 50(1) of the WA]. • A Grant of Letters of Administration “cum testamento annexo’’ As we have already said, sometimes a person makes the Will and in the Will he identifies or names a person to be an Executor, but the person so identified or named, dies before the Testator and the original Will is not amended after such death, or the Executor dies after the Testator but before he obtains a grant. Sometimes the person named in the Will might after the death of the Testator refuse to do the work left to him. He can do this at any time before a court actually grant probate to him and even when he had agreed with the Testator that he would act [section 26 of the WA]. Sometimes the named Executor might not be available to take up the job such as where his whereabouts are not known [section 36(1) of the WA]. Sometimes the person named to be Executor is out of the country and it is not known when he might return [section 37 of the WA]. Sometimes the person may not be available or simply fails to apply for a grant or the Will does not name anyone as Executor. In any of such situations, the Law will provide guidelines on how some other person(s) can be identified or ascertained who can deal with the property of a Testator [sec 36(1) of the WA]. The person identified by the law as we saw earlier will apply to a court for a grant using the same procedure as such used by the Executor, except his oath is called an administrator’s oath and it must state why the Executor is not applying for the grant. A maximum of up to only four persons can be given a grant at any given time [section 30(1) of the WA]. The resultant grant from the court will be letters of administration and since the deceased would have left a Will, the grant will have the Will annexed to Page 11 of 105 it because even if the new person is identified through the guidance of the law, he must still carry out the instructions in the Will. This is what is called “a grant of letters of administration with a Will annexed”, or letters of administration cum testamento annexo. • A Grant of Simple Letters of Administration When a person dies without leaving a Will, the Law will as we have already seen provide guidance on how to identify some person(s) to administer the estate [section 15(1) and (2) and section 16(1) of the ISA]. The person(s) so identified through the guidance of the Law, to administer the estate of a person who dies intestate, must apply to a court to be appointed or to be made an administrator and must still prove to the court that he/they indeed qualify and is/are the rightful person(s) to apply at that time [sec 15(1) ISA]. When appointed, he becomes a simple administrator. He applies to any court with probate jurisdiction [sec 15(1) ISA]. He must apply for a grant in the same way as the Executor or the Administrator cum testamento annexo, except in his case he does not refer to any Will. WHO CAN BE A PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE? Where there is a Will? A. The Executor • What is an executor? An Executor is the person to whom by appointment express or implied a Testator entrusts the execution of his Will [sec 3 of the WA]. He is the person placed in the position of the testator who may collect and get any property or asset of the testator and who may dispose those same assets or property of the testator towards the payment of the debts owed by the testator and who may generally carry out the wishes of the testator contained in his will [section 45 of the WA]. It is an office of personal trust and cannot be assigned inter vivos (among the living). The Estate of Skinner 1958 1 Weekly Law Reports 1043 1046 – in this case, a company Page 12 of 105 which had proved the Will of a Testator entered into an agreement with another company in which the first company was required to transfer its assets and liabilities to the second company. It was held by the court that the first company’s obligations under the grant of probate to the Will could not be transferred or assigned. The Executor acts not of his own account but as the personal representative of the deceased testator’s estate. He is therefore, not entitled to any benefit from the estate unless such is bestowed on him in the Will [section 57(1) of the WA]. An Executor is often confused with a trustee, although usually, the same person is made both Executor and Trustee. The two differ in many respects, but the main difference is that an executor is a PR whose main function is to collect and receive the assets of a dead person, pay the debts of that dead person, and distribute the surplus to those who may be entitled. A trustee on the other hand is an agent of another person whose main function is to hold the property of that other person or some other person. A trustee may hold and distribute the assets, but if he also receives debts owed to the estate, and paid out debts owed by the estate, then he is administering the assets, and if these duties are conferred on him, by a Will, then he is an Executor. Assume an Executor completes administering the assets, that is to say, collecting the assets and paying all the debts owed by the deceased, he is said to be functus officio. He has completed his work as Executor. If there are any assets left in his hands, he technically then becomes a trustee of such assets and hold them in such capacity on behalf of those entitled to them. In re Ponders 1921 CLR 59 – in this case, an administratrix who had cleared all the liabilities of the estate and had ascertained the residue wanted help from the Public Trustee as a co-trustee of the residue. It was held by the court that upon clearing the debts of the estate, she had ceased to be an administratrix and had become a trustee and consequently, the Public Trustee could be appointed as a cotrustee. However, once one becomes an executor, always an executor [Re Timmis 1902 1 Chancellor 106 180]. Page 13 of 105 • Who can Appoint an Executor? Generally, only the testator can appoint an Executor, but there are times when the testator by his Will authorizes someone else to make the appointment. Previously, an Executor of a sole or last surviving Executor of a testator was the Executor of that testator. This still is a case under English Law but section 48 of our WA now provides that on the death of a sole or last surviving executor, letters of administration cum testamento annexo et de bonis non administratis to the original estate must be granted or obtained. This means, that on the death of a sole or last surviving executor, a grant of letters of administration cum testamento annexo (with the Will annexed) et de bonis (relating to the goods/property) non administratis (not administered) will be made or will have to be made. In the past, succession was and under English law still is automatic, as long as each executor proves his testator’s Will and himself leaves a valid Will appointing an executor. • Who may be an Executor? • Infants and persons not compos mentis Section 25 of the WA provides that “any person of or above the age of 21 years and having capacity to enter into contract may be appointed an Executor of a Will”. Section 29(1) of the WA provides that “except as provided by the AdministratorGeneral’s Act, probate may be granted by a court only to an Executor appointed by Will and shall not be granted to a minor or a person of unsound mind”. Section 3 of the WA defines a “minor” as any person who has not attained the age of 18 years. The law stated above sounds somewhat contradictory but the combined effect of sections 25 and 29(1) appears to be that a person irrespective of his age or the state of his mind may be appointed Executor of an estate, but there are two problems; Page 14 of 105 i. As long the appointed person remains under an incapacity, such person cannot assume the office of executor and therefore, no rights or powers of an Executor will vest in such person. ii. As long as the appointed person remains under an incapacity, such person cannot be granted probate by a court. The appointment is not void ab initio for contradicting section 25 because a person can grow into maturity between the date of the execution of a Will and the date of the death of the Testator or a person non-compos mentis may be cured or may recover before the Will takes effect. • A Firm or a Holder of an Office i. A firm or partnership may be appointed but it is the individuals who are partners at the date of the Will who will be able to apply for a grant unless there is a contrary intention in the Will [sec 25 of the WA]. ii. The holder of an office such as the Director of ZRA, a Bishop, a Minister, may be appointed but it will be the individual who will hold that office at the date of the death of the testator unless there is a contrary intention in the Will [sec 25 of the WA]. It is the office being appointed not the individual. Generally, a Will speaks as we shall see later from its date as regards identified or specific individual persons or specified and identified property and from the death as regards persons or property in general [sec 16 (3) of the WA]. The general rule is however, subject to a contrary intention in the Will. • Corporations or Companies i. A Corporation Sole or a Trust Corporation or a Corporation Aggregate may be appointed executor [sec 25 of the WA] ii. A Corporation or a Company which is not a Trust Corporation may be granted probate but may not be granted letter of Administration [sec 31(i) of the WA] iii. Probate or Letters of Administration shall not be granted to a syndic or nominee on behalf of the Corporation or Company [sec 31(3) of the WA]. A company Page 15 of 105 would have problems holding a Bible in front of a Commissioner for Oaths during the swearing of the Executor’s oath but the reason for this would appear to be that • Probate can only be granted to someone identified in a Will or appointed in a Will to be the Executor [sec 29 (1) of the WA]. If a Company is appointed, that Company must be granted Probate and individual will be authorized by the Company to swear the Executor’s oath on behalf of the Company • Letters of Administration should only be granted to those who by law qualify either under intestacy [sec 15(1) of the ISA] or where the Will identifies no executor or where the named Executor fails for some reason to take up his office [sec 36 (1) of the WA]. A company would not normally qualify except perhaps when it applies as a creditor. • How is the Executor Appointed? An executor is usually expressly appointed by the testator in the Will such as “I appoint X and Y both of ………. (hereinafter called “my Trustees”) to be the Executors and trustees of my Will.” [sec 29(2) of the WA]. However, it is not necessary for a testator to actually name his Executor as he may delegate the choice of an Executor to another person. Where there is doubt as to the person intended by the testator, evidence is admissible if the ambiguity is latent (hidden) as where a person with three sons appoints “my son…….” This is a latent ambiguity and evidence is admissible to resolve the ambiguity. See Estate of Hubbuck [1905]. P.129 -- Where a testatrix who had three granddaughters appointed “my granddaughter ………” Evidence was admitted showing which of the three. However, if the ambiguity is patent, as where A appoints “one of my sons”, as in the case of Blackwell (1877 2 P.D.72), evidence was not admissible. The Testator must provide the means by which an Executor can be identified. Page 16 of 105 • An Executor is sometimes appointed by implication if it appears that it was the Testator’s intention though not expressly appointed that a particular individual should act as Executor [sec 29(2) of the WA]. This is so where it appears that some person is required to collect assets, pay the testators debts and distribute the rest of the assets or where a testator says only person A should deal with the estate. A has been held to have been appointed Executor “according to the tenor of the Will” e.g. In the Goods of Russell (1892 P.380) the Will is simply stated - “to carry out this will”. The Testator must provide the means by which an Executor can be identified. An Executor may be appointed to act at some future time or after the happening of some event or for a particular period or purpose only. In such cases the grant of probate will also be limited accordingly. Different Executors may be appointed to perform different functions or in different places or relating to particular assets and grants will follow such appointments. • Renunciation by the Executor We shall see later that a testator can change or revoke his Will at any time during his life time. In the same way, an Executor can renounce his appointment at any time even when he had given his agreement to the testator to act. He can renounce orally in Court or in writing before a Commissioner for Oaths where he must confirm that he has not intermeddled with the testator’s assets [section 26 of the WA read with section 65 of the WA]. Except for the power vested in the Court he cannot be compelled to take up a grant of probate, but he can be compelled to decide whether or not he will take up the office of Executor [section 27 (1) of the WA]. If he fails to decide or to respond after being so compelled, the failure amounts to renunciation. [Sect. 27(2) Wills Act]. If he decides he would take up the office but fails to take any further step within a given period, usually fourteen (14) days, this is considered by the law to be a renunciation of his right to take up the office of Executor [Sec 27(3) WA]. There must be some record of the renunciation filed somehow in the Probate Court; otherwise the renunciation is not effective. Page 17 of 105 Once an Executor has performed some act which can only be performed by an Executor, he is deemed to have accepted the office and may not renounce [sec 26 of the WA/ cf sec 65 of the WA]. Once an Executor has proved the Will, he cannot renounce but if he is for some reason unable to continue to perform his functions as Executor, probate can be revoked [sec 51(2) of the WA]. The Executor will be permitted in proper circumstances to retract his renunciation and the Court may grant probate to him if it considers that it is for the benefit of those entitled under the Will or under the testator’s estate [Sec 28 of the WA]. B. THE ADMINISTRATOR CUM TESTAMENTO ANNEXO What is an Administrator? An Administrator is the person to whom a grant of letters of administration are being made by a court and includes the Administrator General [sec 3 of the WA]. Where there is a Will, but there is no Executor available, or willing to take up that office, this is the person who is appointed by the court to perform the duties and functions that should have been performed by the Executor [sec 36(1) of the WA]. While he is appointed by the court, he must still follow the instructions contained in the Will and for this reason, the Testator's Will is always attached to the document appointing him. Who may be an Administrator? In order to determine a proper person to apply to be an Administrator, the law looks at the person with a beneficial interest under the Will of a deceased. The order of priority generally follows that interest. That is to say, among those beneficially interested in the estate, the one with the greatest interest has priority [sec 36(1) of the WA]. Section 36(1) of the WA sets out the beneficiaries in the order of priority as follows: a. A beneficiary entitled to the universal or residue of the deceased's estate or a personal representative of a beneficiary entitled to such universal or residue (whatever has not been specifically identified…not a question of being mentioned last but of being given the rest of what has not been specified) of the deceased's estate; E.g if the Will says: "I give sunglasses to my first born son; my wrist watch to my daughter Page 18 of 105 Jane, pot of water to my wife, and the rest to Donald." If Donald has died, the PR of the church can apply. b. Any beneficiary under the Will who would be entitled to a grant of letters of administration had the testator died intestate; [usually connected or related to the deceased] c. Any beneficiary under the Will [this person does not need to be connected to the deceased]; d. A creditor of the Testator e. When none of the above is available, or willing to take up the grant, the Administrator General will apply. He can administer either on behalf of those entitled under the Will, or where none can be found, on behalf of the State when he claims bona vacantia. The order of priority must be followed strictly [proviso to sec 36(1) of the WA]. If there is anyone with a prior right, such person must be cleared off first. This is done by showing at oath that no Executor was appointed or explaining at oath why an Executor is not able to apply or that no appearance was made to a citation [sec 27(2) of the WA]. The other reason could be given is where the person named Executor renounced [secs 26, 27(3) and 36(2) of the WA]. When there is a minor beneficiary entitled under a Will, such as where some beneficiary is under the age of eighteen years, or there is someone with a life interest in an estate, the court will not make a grant of letters of administration to one person, but it will do so to at least two persons unless the one who applies for the grant, is a Trust Cooperation which includes the Administrator General or the applicant is an ordinary Company [sec 30 (1) of the WA]. C. A SIMPLE ADMINISTRATOR Page 19 of 105 This is the person to whom a grant of letters of administration has been made by a court [sec 3 of the ISA]. In order to determine the proper person to apply to the court for a grant of letters of administration where there is no Will, the law takes the same route as for an Administrator cum Testamento Annexo. That is to say, it looks at the person interested in the estate as a beneficiary and among themselves the one with the greatest beneficial interest has priority. The persons who are beneficiary interested in the estate of an intestate are determined according to the law applicable to the intestate at the time of his death [sec 2(1) of the ISA]. There are two different systems that are applicable namely: • Where customary law does not apply - for those who died intestate, domiciled in Zambia, and to whom customary law does not apply, The Administration of Estates Act 1925 as amended by later English intestacy law provides the beneficiaries in the order of priority as follows: i. the surviving spouse ii. The children of the intestate and their issue (e.g., their children or grandchildren and so on) iii. The parents of the intestate iv. The brothers or sisters of the intestate of the whole blood (same father same mother) or their issue The above are the only people who will be entitled for a grant where the deceased left a surviving spouse. If there was no surviving spouse, then other relatives can apply in the following order: v. The brothers and sisters of the intestate of the half-blood (only share one parent) and their issue vi. Grandparents of the intestate vii. Uncles and aunts of the whole blood and their issue viii. Uncles and aunts of the half blood and their issue Page 20 of 105 • Where customary law applies - For those who die intestate, domiciled in Zambia after 1989, and to whom customary law applies, the beneficiaries are found in the order of priority in Sec 5(1) as read with section 6 both of the Intestate Succession Act as follows: I. The surviving spouse or spouses II. The child or children of the intestate III. The parents of the intestate The above is called "priority dependents" and are the only ones that can claim for family provision relief equivalent to that under section 20 of the Wills Act which we shall see later [proviso to section 5 of the ISA]. IV. The dependents of the Testate V. The near relatives of the Testate. These are defined as issue, brother, sister, grandparents, and something descendants Failing all those mentioned above, the Administrator General can apply to be made Administrator irrespective of when the death occurs or what law applies. After the AG has been appointed, by the court, he can administer the estate either on behalf of those beneficiary interested in the estate or sometimes when he claims owner vacancy on behalf of the state. [If you cannot find anyone connected to the deceased to be made an Administrator, the AG is always available to be made AG. There are times he can apply however, to be made Administrator even when there are relatives available to be made Administrator] (section 6(b) of the ISA or section 27(2) of the Administrator General's Act). As this person applied to be Administrator was not chosen by the deceased and is applying as we have seen because he meets certain qualifications, it is often necessary for this person to provide some guarantee or assurance to the court that he will perform his duties as Administrator according to Law. He is sometimes therefore, required to provide security for this purpose which we will see later [section 50(1) of Page 21 of 105 the WA or section 28(1) of the ISA]. The AG is not required to provide any security when he applies [section 50(4) of the WA or section 28(4) of the ISA]. When there is a minor beneficiary interested in the estate or there is someone with an interest in the estate, only when the remain alive, the law prescribes that there must at least be two persons as Administrators unless the one applying is a Company which includes the AG. [section 30(1) of the WA or section 16(1) of the ISA]. CAVEATS AND CITATIONS A. CAVEAT 1. What is a Caveat? (a.k.a a roadbloack) A caveat is a notice in writing lodged in the Probate Registry, cautioning the Registrar that no grant is to be sealed in the estate of the deceased named therein, without notice to the party who has lodged it. No grant will be sealed if a Registrar has knowledge of an effective caveat but a caveat is not effective to prevent the sealing of a grant on the day of which it is lodged, it only becomes effective on the next day after lodging. The person by whom or on whose behalf a caveat is entered is called a caveator. Any person who wishes to prevent or to be notified of the issue of a grant of representation or who has or claims to have an interest in opposing a grant and wishes to oppose it may enter a caveat. 2. What is the purpose of a Caveat? Some of the purposes for which a caveat may be entered are: a. To give time to the caveator to make enquiries and enable him to determine whether there are grounds for opposing a grant. b. To give him an opportunity of raising any question in respect of the grant or to prevent anyone else applying for a grant c. As a step preliminary to an action relating to a grant (solemn form probate) Page 22 of 105 3. What are the contents of a Caveat? A caveat is normally in some prescribed form but if no form is available, it must have a. the full names of the deceased, b. the date and place of death, c. the full names of the caveator; d. an address for service within easy reach of the principal probate registry; e. including a date of entry and; f. it must be signed by the caveator or his lawyer. The caveator need not disclose his interest at this stage. 4. What is the effect of a caveat? As long as an effective caveat is in place, no grant will issue to anyone except the caveator himself until it has been removed. 5. How can a caveat be removed? There are four methods: a. By a warning - a warning is a notice to the caveator disclosing the interest of the person opposing the caveat and requiring the caveator to disclose his interest in the estate and possibly his intentions and wishes regarding the Administration of that estate. This is drawn in the manner of a Writ of Summons on a prescribed form. The response of the caveator to the warning depends on his reasons for lodging a caveat: i. If his reason for lodging a caveat is to oppose a grant, because he has interests contrary to those of the caveator, then he must enter an appearance in the prescribed form and within the prescribed period. ii. If his reason for lodging a caveat is not to oppose a grant but merely to be notified of the application for a grant, so that for instance, he can commence proceedings against the estate and needs to know who to sue and when to sue, then Page 23 of 105 he must within a prescribed period issue and serve Summons for Directions. He must respond to a warning as failure to do so will defeat the caveat or render not effective. b. By withdrawal - a caveator may withdraw the caveat at any time before he enters an appearance to a warning. c. By an Order of Court - the Registrar or a Judge can order the removal of a caveat d. By effluxion of time - a caveat is only valid for 6 months at a time but it is renewable for successive periods, but it should be remembered that a caveat has no effect on the day it is entered in court, so that on the date of renewal it cannot stop a sealing of a grant on that day. B. A CITATION 1. What is a Citation? (a.k.a. A bulldozer) It is an instrument which issues from the Probate registry signed by the Registrar under a seal of the Court. [Difference with a caveat - goes into court: citation - comes out of court]. It will indicate why it has been issued and will show the interest of the party issuing it, and call upon the party cited to enter an appearance and take the step(s) stipulated in the citation. A citation will indicate what will happen if no good cause is shown to the contrary. It is like a Writ of Summons. 2. What is the purpose of a Citation? It is a way of proding or encouraging someone to do something that he ought to do otherwise another person will take some other action. No person can obtain a grant of representation, when they are in existence, people entitled to a grant in priority to that person, without somehow removing those people from their superior positions [section 15(1) of the ISA or section 36(1) and (2) of the WA]. Sometimes people will neglect to perform their lawful duties unless they are pushed so to do. In order to compel someone, to do what he ought to do, without pointing a gun at him or using some other form of means, a citation is the tool to use. The citation can be used in all contentious and non-contentious cases such as to compel someone to: Page 24 of 105 a. Accept or refuse to take up a grant b. To show cause why he may not be compelled to take up probate where the named Executor has accepted his office by intermeddling in the estate. But, once he has obtained probate, an executor cannot be compelled to act by anyone except the court exercising its control over him. c. Propound a Will or some Testamentary paper otherwise someone else can apply for a grant as if the deceased did not leave a Will, or as in an intestacy. d. To compel an Executor or an Administrator to bring in a grant of probate or a grant of administration made to him in order that it may be revoked (solemn form probate or contentious business). 3. What is the effect of a Citation? When a person is served with a citation, that person must within a specified period, respond by entering an appearance to the citation in court. If there is no response to the citation, the person who extracted the citation can proceed with whatever action was indicated in the citation [section 27(2) of the WA]. If there is a response, that is to say an appearance has been entered, but no further action is taken by the person cited, the effect is the same as non-appearance and the person who extracted the citation could proceed with his next move. THINGS THAT CAN HAPPEN IRRESPECTIVE OF WHETHER OR NOT THERE IS A WILL (In the exam) There are certain situations or things that will happen or need to happen irrespective of whether there is a Will or not, in relation to a personal representative. 1. The Executor de son tort (The Executor without authority) A good-natured person may sometimes without being appointed either expressly or by implication and without taking the trouble to apply for a grant or letters of administration carry out acts or duties characteristic of a personal representative. The good-natured person in such a situation is said to be intermeddling with the goods of Page 25 of 105 a deceased person and makes himself an intermeddler or Executor de son tort [section 65(1) of the WA or section 6(1) of the AGA]. Slight acts such as taking possession of a deceased person's property, collecting a deceased person's Will from a place of safe custody, demanding debts of a deceased person and receiving them, and paying a deceased person's debts will all render the person concerned liable as an Executor de son tort, unless he is a named Executor in a valid Will. In the case of payment of the deceased's debts, there will be no intermeddling if the good Samaritan pays from his own pocket and does not use the assets of the deceased. Carrying on a business of a deceased is intermeddling but mere acts of humanity such as burying the deceased, locking up his goods for security is not intermeddling. The idea of an Executor de son tort implies a wrongful act. The Executor de son tort can be sued by the rightful Executor, Administrator, Creditor or a beneficiary. His liability is however, limited to the assets which came into his hands unless he is one of many, then he is liable for whatever may have been done by the others with his authority. Any act performed by him, that would have at some time have been performed by the correct PR, will bind those PRs and the estate. 2. The Procedures used to obtain a grant of Representation When there is no dispute relating to an estate, whether it be the validity or any other matter, relating to a Will or its contents (that is where there is a Will), or a choice of a PR, or indeed any other matter relating to an estate, whether there is a Will or not, the court will make a grant purely on the strength of the documents lodged. In the case of a testate estate, these will be [section 29(1) WA]: a) The Executor’s Oath b) The marked Will c) The declaration of the testator’s estate d) The fee sheet e) The money being paid to the court In the case of an intestate estate, these will be [section 50(1) ISA]: a) The Administrator’s Oath Page 26 of 105 b) The declaration of the Intestate’s estate c) The fee sheet d) The money being paid to the court The above is known as common form probate or non-contentious business. That is, the method to be used where there is no dispute or no possibility of a dispute. However, where there is a dispute, or a possibility of a dispute relating to an estate, a different procedure becomes necessary. If a dispute or a possibility of a dispute relates to a question of who should administer an estate, one should always bear in mind that the law prefers a person chosen by the deceased where there is a Will [section 36(2) WA]. Where there is no Will, the law prefers a beneficiary under the estate [section 50(1) ISA]. Where there is a Will, but no one chosen by the deceased to administer the estate, the law again prefers a beneficiary under the Will [section 36(1) WA]. Among those beneficiaries, the one with the greater interest has priority. In order to resolve a dispute, it is advisable for the parties to such dispute to actually commence legal proceedings against each other. The one initiating the action normally starts by lodging a caveat. This will caution the Registrar against sealing any grant in favour of anyone except the person who lodged the caveat. This will normally be followed by a citation depending on the party who wishes to commence the action. In arriving at a decision, the court will be assisted in an intestacy by section 15(2) or (4) of the ISA, and where there is a Will by section 36(2) of the WA. E.g. Chinyanta v Chiwele 2007 ZLR. The court does not appear to have addressed its mind to section 15 of the ISA although its attention was specifically drawn it. Unfortunately, this is the official interpretation now until the issue is reviewed, or the case overruled. Anyone interested in an estate may commence or join legal proceedings in court where he makes anyone with opposing views or anyone perceived to have opposing views or likely to cause problems a plaintiff or defendant in the action. This will be conducted like any other civil court proceedings with witnesses etc. When the court decides in favour of making a grant, after having heard evidence from all the interested and participating parties, the grant will bind who was a party or who could have been a party to it. If a person is aware of a dispute or a matter in Page 27 of 105 court involving an estate in which he has an interest, it is better for such person to apply to join the proceedings either as a co-plaintiff or a co-defendant. Whether he joins or not, the decision of the court will bind such person. This procedure is called solemn form probate or contentious business. Solemn form probate would appear to be better than common form probate because everyone interested in the estate can participate at that time and be able to adduce any evidence in support of their claim or interest. A grant of representation obtained through common form probate can be defeated and revoked quite easily on the production of some contentious issue affecting the Will or its contents or the estate whether there is a Will or not. SECURITY FOR ADMINISTRATION The PR must always act not for his own account but as a representative of or the alternative of the deceased or his estate and must therefore not derive a benefit for himself unless he is a beneficiary in his own right as a result of a gift under the Will where there is one or he is a beneficiary under an intestacy [section 34(1) ISA or sec 57(1) WA]. While a PR must not derive a benefit from his office as PR, he is personally liable to the estate for any loss or for any negligence in handling an estate or any mismanagement or misapplication of the assets of an estate. He is liable for worst or devastavit. The responsibility placed upon a PR is a heavy one as all the property or assets of the deceased are vested in him or are in his hands to administer not for his own benefit but for that of the estate and those who may be interested under the estate. For this reason, it is important and necessary that there is some assurance or guarantee that a PR will carry out or perform his functions or duties as PR according to a Will where there is one or according to the law where there is no Will. A PR who is an Executor is not required to provide any such assurance or guarantee for the due administration of an estate other than his own personal undertaking. This is because the testator chooses as his Executor a person in whom he has faith or who he trusts that he or they would carry out the instructions diligently and properly according to law. Page 28 of 105 The Administrator on the other hand is appointed not out of trust but because he meets certain qualifications. It is however, not everyone who meets the qualifications who will get appointed as the court considers a general character of a person before that person is appointed such as that person’s age or his state of mind. As the administrator is appointed, not out of trust, the law requires that he provides some assurance or guarantee to the court that he will perform his duties according to law [section 28(1) ISA or section 50 (1) WA]. The law therefore, requires the Administrator to commit himself to the court to the performance of those duties. In the past, the law required him to execute a James Bond in favour of the Probate Registrar which contained conditions under which the Administrator was required to act in the performance of his duties as PR. The conditions were similar to those in the Administrator’s oath where he submits himself to the control of the court [section 45 (1) (c) WA]. The security was that the Administrator armed himself to the probate court in a sum equal to double the gross value of the estate to be administered. In the event of a breach of those conditions, the Administrator would be compelled to pay to the estate through the court a sum equal to or up to double the gross value of the estate. The bond was required to be attested or witnessed by an official of the Probate Court or a person authorised to administer oath. When the conditions of a bond were broken, an interested party could apply to the Probate Registrar for the enforcement of the bond. The Probate Registrar or the Probate Court would upon such application assign the bond to some person who would then enforce the bond. Once an order for an assignment was made, the person named as assignee could sue upon the bond in his own name as if the bond had originally been given to him and he could sue even before the assignment was actually made. Whatever he recovered would be held on trust for all those interested in the estate. As additional security or protection, the law usually required that the bond was supported by two sureties but sometimes one surety was sufficient. Now, no bond is normally required but the security is still provided by the sureties as a particular situation requires [section 28(1) ISA or section 50(1) WA]. This will normally be required where the person applying is: a) A creditor of the estate b) An attorney of the person entitled Page 29 of 105 c) Applying as Administrator durante minore or durante demencia d) The applicant is a non-resident There is no security required when the one applying to be an Administrator is a cooperation or a company which includes the Administrator General [section 28(4) ISA or section 50(4) WA]. There are times when the court will dispense with the security or sureties altogether and there are times when the court will demand a bond. RESEALING OF GRANTS The general rule is that if a person dies and leaves property of any kind in this country, a grant of representation must be obtained here in order to deal with it. It is also a general rule that if a deceased left property in any country it is necessary that a grant be obtained in that country in order to deal with it. Any person who deals with the property of such deceased without a grant of representation or being appointed either expressly or impliedly in a valid Will becomes an intermeddler or an Executor de son tort [sec 65(1) WA or sec 6(1) AGA]. However, instead of applying for a grant in this country where the deceased died domiciled elsewhere, and left assets in this country, it is possible sometimes to merely reseal here a grant of representation which was made in another country. The effect of resealing a foreign grant where this is possible, is the same as if the foreign grant was actually issued in this country [section 3 Probates (Resealing) Act or section 54(1) WA]. If the deceased left no property in this country, no grant is necessary here, but if he died here leaving property in another country, a grant here may be necessary which may then be resealed in the country where the property is situate if such country has laws which would accept a grant for re-sealing. As the re-sealing has the same effect as a grant obtained here the procedure to re-seal the grant is basically the same. The main difference is that the PR who has obtained the foreign grant need not apply for a re-sealing in his own name as he can authorise someone in writing to do it for him here. It is usual but not necessary for the written authority to take the form of a power of attorney to someone in this country. The person so authorised in writing Page 30 of 105 must advertise his intention for a re-sealing. The advertisement must be made once in the Government Gazette and twice in a local daily newspaper. This enables those persons resident in Zambia who may be interested to make their claims in the estate. He must also indicate the gross value of the estate in this country in the Executor’s oath or the Administrator’s oath. If the foreign grant was a “cum testamento annexo” or a simple administration security will be necessary. That is to say, if what is required to be re-sealed are letters of administration. However, it is possible to produce evidence that adequate security was provided in the country of origin of the foreign grant. He must then prepare and lodge the following: a) The Executor’s or Administrator’s oath as the case may be b) The original Grant c) Two or more other court sealed and certified copies of the foreign grant d) A copy of the Will where there is one e) A declaration of the Zambian estate f) Evidence of advertising g) The fee sheet h) The money In the alternative, he prepares and lodges: a) The Executor or Administrator’s oath as the case may be b) Three of more court sealed and certified copies of the foreign grant c) A Declaration of the Zambian Estate d) Evidence of advertising e) The fee sheet f) The money The court will return a copy of the foreign grant and a copy of the foreign Will where there is one and send it back the original grant and any extra copies duly received in this country. After a grant has been re-sealed, notice of the re-sealing must be advertised usually by the Registrar but at the expense of the estate. This then enables the PR to deal with the estate in this country. Page 31 of 105 SPECIAL AND LIMITED GRANTS a) A Grant Caeterorum This is grant where there was a grant initially made limited to a particular portion of the deceased’s estate and then it becomes necessary to obtain a grant relating to the rest of the estate [section 43 WA]. b) A Grant Save and Except As the title implies, this is made but to exclude certain portions or parts of the estate when the bulk of the estate is to be administered [section 42 WA]. This is what comes before Caeterorum, that is to say, the grant caeterorum is dealt with first. If you want to deal with at is left, you get caeterorum. c) A Grant de bonis non Administratis (A grant relating to those things that have not been administered yet) This is when an Executor or an Administrator dies or is for some reason unable to complete his job. After obtaining a grant a new grant is made relating to the portion of the estate not yet administered. [section 26 ISA or sec 36(1)(d) & sec 48 WA]. d) A Grant till Will be found If it is known that a Will existed after the death of the Testator, but it cannot now be found, a grant of letters of administration till the Will be found will be made. When the Will is found, the limited grant is revoked, and a new and substantive grant made [section 32(1) WA]. e) A Grant to Attorney When an Executor (section 37) or an Administrator (section 38) is absent from Zambia but there are assets that require to be administered here, a grant will be made to a duly constituted Attorney of the absent Executor or Administrator limited until the Executor or the Administrator is able to get a grant in his own name in this country. If there is an Executor outside Zambia, the Attorney grant will be made with the Will annexed. The Attorney Grant must be revoked when the Executor or Administrator return to Zambia as they must obtain their own grant. When there are more than one Executors appointed in a Will, notice must be given to the other Executors before the Attorney grant will be made. Page 32 of 105 f) A Grant Durante Absentia When an Executor or an Administrator has obtained a grant of representation and goes out of the country before finalising the administration, another person (s) with interest in the estate may apply for a grant during the absence. The grant durante must be revoked upon the return of the original Executor or Administrator. g) A Grant Durante Minore Aetate This is made when the person primarily entitled to a grant whether of probate or otherwise, is an infant (anyone below 18). It is normally granted to a guardian or someone selected by the court or the infant where he is at least 16years old. When the infant is also a beneficiary interested in the estate, a grant durante minore will be made to at least two persons or a trust corporation [section 16(1) ISA or section 30(1) WA]. h) A Grant Pendete lite Where there are proceedings, touching on the validity of a Will, the right to administer the estate or for revoking a grant, the court may appoint an Administrator pendete lite (pending the resolution of the issue) [section 18 ISA or section 40 WA]. However, some Writ must have actually been issued before such grant can be made, because until then, there is no lis pendens. Even where a caveat may have been issued, warned and an appearance entered to the warning, there is no lis pendens until the Writ has actually been issued. i) A Cessant Grant When a grant limited as to time such as a grant durante minore ends, because the specific period allocated to it has ended, a Cessant grant is made [section 27 ISA or section 49 WA]. This grant differs from a grant de bonis non in that a cessant grant becomes necessary when the period allocated to an earlier grant ends, while a de bonis non on the other hand, the person to whom a grant was originally made is no longer able to continue performing his duties as PR. j) A Grant Ad Colligenda Bona When no next of kin, a creditor, or other person applies for Administration and there is danger to the estate such as where the estate consists of some perishable Page 33 of 105 assets, or is perishable in nature, and requires to be preserved, a grant for the collection of goods will be made. As the name implies, it will be limited to the collection getting in, or receiving assets, and doing things or acts necessary to preserve such estate. k) A Grant of Double Probate When a Testator has appointed more than one Executor, and only one proves the Will, power is reserved for the other Executors to come in and prove the Will [section 29(3) WA]. When this happens, the new grant does not replace the first but will run concurrently and hence the name double probate. l) A Grant Ad Litem When there is litigation involving the estate and the proper representatives will not act, the court may appoint someone to act for the purposes of the proceedings. The decision of the court will bind the estate. This grant differs from a pendete lite in that the person appointed ad litem is ether the plaintiff or defendant on behalf of the estate while the other takes no part in the proceedings in court. m) A Grant Durante Dementia Where a person entitled to a grant is incapable because he is non-compos mentis as envisaged in section 29(1) of the WA, the Registrar will issue a grant to some other person for the duration of the incapacity. If there is a Will, the grant will be a cum testamento but if there is no Will, it will be a simple letters of administration durante dementia. AMENDMENT OF REVOCATION OF A GRANT 1. Amendment a) General In non-contentious cases, the Registrar of the Probate court has power to amend a grant where he is satisfied that it should be done. This is the case where there is some error or problem which is not serious such as the spelling of a name, a wrong address, or some problem considered by the Registrar not to be serious. An application for Page 34 of 105 amendment is made by lodging a grant together with an Affidavit in support explaining the circumstances giving rise to the application. The affidavit should also state the action that requires to be done. The application must be made by a holder of a grant or with his consent. Where the error was made by the court, when making the grant, no Affidavit is usually necessary if the grant is returned to the court for rectification within a reasonable time, usually 14 days. b) Value of the estate If the error relates to the gross value of the estate to be administered, as where more assets are discovered after the grant, additional security for the due administration may where applicable be required unless the court directs otherwise, or, the security given originally is sufficient to cover the new value. 2. Revocation a) General Where a serious error or problem is discovered, the court will not amend a grant but will revoke it and issue a new one. This applies to both contentious and noncontentious cases. In non-contentious cases, the Registrar of the Probate Court has power to revoke a grant. The process to lead to the revocation of a grant is similar to that of an amendment in that, a grant must be lodged in court together with a supporting Affidavit and the application must be made by the holder of the grant or with his consent, except: i. An executor who has proved his testator’s Will cannot apply to revoke the grant unless he is able to apply in another capacity. ii. where it is not practicable for the order to apply or give his consent, a court order can be obtained by someone else. A grant obtained through contentious business is revocable for any of the reasons applicable to non-contentious cases except that this may usually be more difficult to establish since the grant will have issued after the conclusion of normal court proceedings. b) Grants for Revocation Page 35 of 105 As already seen, serious errors or problems cannot be resolved by amending a grant, but these call for a full revocation. Examples of some of the errors considered serious are [section 51(1) WA or section 29(1) ISA].: i. Where a grant of administration has been given and a Will is later discovered ii. Where a grant of probate has been given and a later Will or codicil is discovered iii. A grant of Administration to one person when the law demands a grant to two such persons (minority or life interest) iv. Where a grant was made to a wrong person v. A grant of probate to two or more persons and one of them becomes non-compos mentis prior to the winding up of the estate. The grant will be revoked and a new one issued to those who are still normal with power being reserved for the mad person to come back when he recovers. vi. The deceased turns up very much alive Section 51(1) of the Wills Act and Section 29(i) Intestates Succession Act. However, a Grant of Representation will not and should not normally be revoked on the ground of misconduct on the part of the Personal Representative even for a grave misconduct. The estate and the beneficiaries are protected not by revoking a Grant but rather by: i) The control which the Court exercises to secure the due administration of the assets of a deceased person in the interests of the beneficiaries and all other parties interested in an estate. (Section 45(1) Wills Act and Section 29(i) of the Intestates Succession Act. Remember the contents of Executor or Administrators Oath! ii) The fact that beneficiaries can follow the assets in the hands of persons who wrongfully receive them from the Personal Representative, see: Ministry of Health v. Simpson 1951 A.C. 251. In that case, the Executors of an estate, acting under a mistake of law, gave the residue of the estate to a charity believing that the gift was valid when it was not. In an action by the next-of-kin of the deceased, it was Page 36 of 105 held, the next-of-kin had a direct claim in equity against those to whom the residuary estate had been wrongfully distributed. Where there is a complaint against a Personal Representative, for misconduct or any other reason, the remedy is not to apply to Court for the removal of the Personal Representative or the revocation of a Grant but rather to apply to the Court for the Court to exercise its control over the Personal Representative by demanding that the Personal Representative explains to the Court how he has gone about administering the estate. If the Court is not satisfied with the explanation and it considers that it is in the interest of the estate and the persons beneficially entitled thereunder, the Court may suspend or remove a Personal Representative (Section 51(2) of the Wills Act or Section 29(2) of the Intestate Succession Act). (c) Effects of Revocation Until it is revoked, a Grant is effective against the whole world and any act performed by the holder of a Grant binds the estate and until it is revoked no other Grant can be issued. H. POWERS OF PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVES We have seen that an Executor gets his power to act as a personal representative from the Will while an Administrator gets his from the grant. We have also seen that as soon as a personal representative becomes such personal representative all the property and liabilities of the deceased vests in such personal representative (Sect. 44 (1) Wills Act and Sect. 24 (1) Intestates Act). As soon as the property of the deceased vests, the personal representative has by law the same powers to do as he pleases, in the course of administering an estate, as any other person would have over his own property. Thus, a personal representative can sell, mortgage, pledge, lease and make any disposition which is necessary in the due Page 37 of 105 administration of an estate (Section 45 (2) Wills Act or Sect. 19(2) Intestates Act) and for that purpose he may even recover possession from a beneficiary. See (Williams v. Holland 1965 1 WLR 739). However, the general rule is that a personal representative has no authority virtute officii, or by virtue of being the personal representative to carry on the business of the deceased and to use the assets of the deceased already being used in the business. He may carry on the business when it is intended to sell the business as a going concern or where he is authorized to carry on the business in the Will as where there is a power in the Will to postpone the selling. A sole Personal Representative has the same powers as two or more Personal Representatives. The requirement that capital money arising out of a Trust for sale shall always be paid to two Trustees or a Trust Corporation, does not apply to a Personal Representative when he acts as such. The exception is when the Personal Representative is an Administrator and there is a minority interest or life interest as the Court cannot or should not grant letters of administration to one person unless it is a limited grant such as a pendete lite or the grant is made to a Corporation which includes the Administrator-General. A Sole Executor is not affected by the need for two Personal Representatives even where there is a minority or life interest. However, only a maximum of four persons can be granted representation in respect of the same estate at any given time (Section 30(1) Wills Act or Section 16(1) Intestates Act) and; See (In the Estate of Holland [1936] 3 All ER 13). In that case, a Testator by his Will appointed four persons as Executors of his Will, and after certain bequests appointed a fifth person to be a literary Executor in respect of certain papers. The usual Executors’ Oath was sworn by the four general Executors for a grant to them of probate to the estate Save and Except the papers in respect of which a fifth person was appointed literally Executor. The Oath was refused by the Probate Registry on the ground that only a maximum of four Executors can be granted probate Page 38 of 105 in respect of any property at any given time. The Executors went to Court asking that the Oath tendered by them be accepted. Held: as the Oath was effectively asking for a grant to five persons, it contravened the law and ought not to be received. In the case of personalty, where there are two or more Personal Representatives, their authority is both joint and several so that one can dispose of pure personalty without the concurrence of the others. As regards land all the Personal Representatives to whom a grant has been made must join in order to pass title. Those entitled but who have not been granted representation need not participate as they would not be able to prove their title. Anyone dealing with a Personal Representative for value is not concerned to enquire whether the disposition is a proper one. The title of the purchaser will not be affected by the revocation of a grant. When you hold a grant, you have valid evidence of your office until the grant is revoked and anything done while in office binds the whole world. I. DUTIES OF A PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE (1) Possession and Control over Assets The first duty of a personal representative is to take possession of the assets of the deceased or assume control over them with due diligence as soon as he properly can. He does this, normally, by registering his interest against each asset but, as this will require some proof of his title, it is done after a grant of representation has been obtained. In the case of land, the grant must be registered against the title to that land within 12 months from the date of the grant failure to which renders the grant void against that land. In the case of other assets such as money in a bank, insurance policy on the life of the deceased and other assets in the hands of third parties, the grant must be produced to such bank, insurance company or other third party for noting or Page 39 of 105 registration. The registration or noting of the grant will establish a personal representative’s possession or control over such asset. After taking such possession or control the assets will be held by the Personal Representative according to whether the deceased left a Will or not. Where there is a Will these will be held according to what that Will says and where the deceased died intestate according to the law relating to intestacy. Where there is an intestacy the personal representative will hold the real property on Trust for sale and any personal or movable property on Trust to call in sell and convert into money such part of it as does not already consist of money but has power by law to postpone the selling and conversion (see Section 33 Administration of Estates Act 1925). In the case of intestacy, “Personal Chattels”, must not be sold, unless these are required for purposes of administration. These are generally defined as “clothing, articles of personal use or adornment, furniture and furnishings, appliances, utensils and all other articles of household use or decoration, simple agricultural equipment, hunting equipment, books, motor vehicles and consumable stores but does not include chattels used for business purposes, money or security for money” (see Section 3 of the Intestate Succession Act 1989). Personal Chattels are basically everything that goes to make a home but not the home itself. The Intestate Succession Act 1989 does not appear to have affected this provision of the law. The general position, therefore, is that as soon as a Personal Representative becomes such all the assets and liabilities of the deceased vest in the Personal Representative who has power to change all or any asset into money by sale but has power to hold on to an asset for as long as he thinks fit. (2) Payment of Debts The second duty of a personal representative is to pay the debts and liabilities of the deceased. This is known as the Administration of Assets. Administration of assets is the obligation of the Personal Representative to pay the funeral and testamentary Page 40 of 105 expenses, the debts and other liabilities of the deceased using or out of the property or assets of the deceased. A personal representative owes a duty to creditors and beneficiaries alike to carry out his obligations diligently. This usually requires that a Personal Representative must complete the administration of the assets within the Executor’s Year i.e. one year from the death of the deceased. In general, until then, he is not bound to distribute the estate of the deceased. He cannot be compelled to distribute any asset to anyone before the end of the Executor’s Year, but he may choose to do so at his own discretion. It is prudent for a Personal Representative to wait until the end of the Executor’s Year as, we shall see later, before any distribution. Any debts that carry interest must be paid with interest. The personal representative also has a duty to perform all enforceable contracts of the deceased. When the estate is solvent, he must pay all debts but when it is not solvent he has a duty to observe the order of payment which has been prescribed by law. If the personal representative pays out a debt of a lower degree knowing that there is a debt of higher degree, this amounts to an admission of assets or devastavit and the Personal Representative will be personally liable to pay the debt of a higher degree. An estate is insolvent if at the date of death of the deceased it was sufficient to pay the debts in full but not the Administration expenses as well. Whether solvent or insolvent the general rule is that all creditors must be paid pari passu. In an insolvent estate the rule is modified by the fact that certain debts are preferred, and others are deferred. In the past it used to be difficult to decide how an insolvent estate should be handled as many different methods were used. As a result of such problems in resolving insolvent estates, the law particularly the Administration of Estates Act 1925 introduced a uniform set of rules. The rules, simply stated, are that in any insolvency the rules relating to Bankruptcy must apply. The order of priority of payment of debts is therefore as follows: Page 41 of 105 (a) Unsecured Creditors (i) Administration Expenses These are funeral, testamentary and the expenses of managing or attending to an estate. Funeral expenses are those that are reasonable having regard to the position of the deceased in society and testamentary expenses are those incidental to the proper performance of the duty of a personal representative. (ii) Preferred Debts These are set out in Sect. 2 (i) of the Preferential Claims in Bankruptcy Act 1995 or (Cap 83) and include municipal rates incurred by deceased within one year prior to death. One year’s government taxes, wages or salaries due to deceased’s workers incurred within 3 months prior to deceased’s death etc. (iii) Ordinary Debts All other debts are payable pari passu. (iv) Deferred Debts These are set out in Sect. 2(i) of the Preferential Claims in Bankruptcy Act 1995 or (Cap. 83) and include loans due to a surviving spouse, loans repayable depending on the profits or a vendor’s share of profit from a sale of business. These are postponed until all other debts have been settled. (b) Secured Creditors These have four choices: (i) Hold on to security until redeemed. (ii) Realize security and prove for the difference. (iii) Value the security and prove for the difference or (iv) Surrender the security and prove for the whole debt. (c) Source of Money to Pay Debts (i) Testate Estates Where the estate is solvent, and the various properties of the deceased have been left to different beneficiaries, it has to be decided in what order the Page 42 of 105 Personal Representatives are to resort to these properties for payment of debts and therefore which of the beneficiaries are to suffer. (See Abatement later) The Administration of Estates Act 1925 provides that the real and personal property of the deceased shall, subject to certain rules and provisions, be applied towards the discharge of funeral testamentary and administration expenses, debts and liabilities of an estate in the following order: (a) Property not disposed of: These come first subject to retention thereout a fund to meet pecuniary legacies. An example of property not disposed of would include a gift of residue which fails as where a testator leaves a gift of residue equally to my two nephews A & B and A dies before the Testator. The portion which should have gone to A is not disposed of. (Sec 16(10) Sec 16(8) and Sec 18 of the Wills Act) Wills Act). (b) Residuary gift. This comes second subject to retention as above. (c) Property provided for payment of debts. (d) Property charged with debts. (e) Pecuniary legacy fund or General legacies. (f) Specific gifts or specific legacies. (ii) Intestate Estates Where there is intestacy, we have already seen that as soon as the Personal Representative becomes such Personal Representative i.e. when the court has made a grant of representation to him, all the assets and liabilities of the deceased vest in him. When that is the case Section 33 of the Administration of Estates Act 1925 (Sec 5(1) of the Intestate Succession Act) also states that the Personal Representative shall hold all the assets of the deceased on Trust to convert into money such assets as are not already in money. The only question to be decided is whether the estate is solvent or insolvent. When it is solvent all debts must be paid and when it is not solvent the Personal Representative must observe the laid down rules for the settlement of insolvent estates as stated under testate estates. Page 43 of 105 3. Distribution of Assets (a) Future Liabilities When the Personal Representative has paid the debts, he must advertise for all possible claimants or creditors stating his intention to distribute and requiring any person interested to send their particulars of claim within a stated period (See Section 29 Law of Property (Amendment) Act 1859 or Section 27 of Trustee Act 1925). The effect of the advertisement is that the Personal Representatives may distribute the assets to those entitled or to those whose claims they have notice without being liable to other persons. This offers protection even from claims by those beneficiaries who made belated claims. It does not, however, prevent claimants following the assets in the hands of recipients except purchasers for value. It does not protect a Personal Representative who is careless or negligent in carrying out his duties. After such advertising, he must still make provision for any liabilities which may not be known at that time, but which may become apparent much later. He must also take into consideration the possibility of a member of the deceased’s family or dependent (as we shall see later) complaining that there has been no reasonable or adequate provision under the Will or under the intestacy law (Section 20 Wills Act or Sect. 5 Intestates Act). (b) Distribution of Residue Having paid the debts and provided for possible future liability, he must set aside sufficient funds to meet pecuniary legacies made by a Will, where there is one. After that he must then distribute what is left to those entitled according to the Will (if any) or to the law relating to intestacy unless there are proceedings under Section 20 (above) or the equivalent under an intestacy. For this reason, it is advisable or prudent for the Personal Representative in normal circumstances to wait for the Executor’s Year before he distributes any asset. (We have seen this and will see again later). Page 44 of 105 During the minority or life interest of any beneficiary and pending the distribution of the estate, the Personal Representative may invest the residue in any investments authorised by law or by the Will where there is one. (c) Ownership of Property Sometimes the question of who owns the property between the date of death and distribution causes problems. We have seen that when a Personal Representative becomes such Personal Representative all the property and liabilities of the deceased vests in that Personal Representative. We are also told that he is a representative and we have seen and shall see later that he must not derive a profit from being a Personal Representative, his job being merely to collect the assets, pay the debts and distribute the rest to those entitled with nothing for himself unless he is one of those entitled according to the Will or under the law relating to intestacy. In spite of the above, it is wrong to say that because the Personal Representative’s position is a fiduciary one or one of trust, the Personal Representative holds only the legal estate while the beneficiaries hold the beneficial interest. The correct position is that all property of a deceased person vests in the Personal Representative. He is required by law to pay all the debts of the deceased (Sect. 45 Wills Act or Sect 19 Intestates Act) and it is from the property or assets of the deceased that he must find the means to pay and as a result no beneficiary is entitled to any property of the deceased until the Personal Representative has actually assented to that property. It is only then that it can be said with certainty that a particular asset will not be required to meet the debts of the deceased. The only exception to this position is where an asset is specifically given by Will to a particular beneficiary. This exception applies only because equity treats that as done which ought to be done. Equity will, in this case therefore, say that the legal estate is in the Personal Representative while the beneficial interest vests in the beneficiary at the deceased’s death. However, despite this position of equity, if the particular property is required to meet the debts of the deceased, the Personal Representative can still dispose of that asset to the detriment of the named beneficiary. The interest of Page 45 of 105 a beneficiary in any asset before assent is therefore only “a floating interest” or “floating equity” which may or may not crystallize. Even in a case where a person is the only one entitled under an intestacy, he is not “entitled to an interest” in a house which forms part of the assets not administered and for this reason or in such circumstances a surviving spouse who has a right in a matrimonial home under an intestacy has no locus standi to defend an action for possession of it. See (Lall v Lall 1965 1 WLR 1249). In that case the widow of an intestate tried to defend an action for possession of the matrimonial home, in which she was residing, on the ground that she had a right of appropriation of the home which gave her sufficient interest in the home to give her a locus standi as a defendant. No grant of representation had been made at that time. Held the right of a surviving spouse to require the matrimonial home to be appropriated to his or her interest in the estate of the deceased spouse did not give the survivor any equitable interest in the matrimonial home nor a locus standi to defend. Section 9 of the Intestate Succession Act 1989 does not affect the prior interest of a Personal Representative for purposes of administering an estate. The Personal Representative may even permit a person entitled to property to occupy such property before an assent, but it does not prevent the Personal Representative from resuming possession or selling such property for purposes of administration. In order for a beneficiary to have a beneficial interest in an asset there must be an assent from a Personal Representative. Where the asset is land the assent must always be in Writing and by Deed but it can be informal where the asset is not land. In some cases the assent on its own may not be able to pass title as where a Personal Representative assents to shares in a company for until the transfer of shares is registered by the Company the title will not pass. (d) Protection of Beneficiaries Page 46 of 105 heApart from the limited protection afforded by equity, regarding specific gifts, the rights of beneficiaries are protected not by them having a beneficial interest in an asset but rather by the fact that the Court has control over Personal Representatives whether there is a Will or not to secure the due administration of an estate for the benefit of beneficiaries and those who may be concerned. This is the protection available. Remember the contents of the Executor’s Oath or the Administrator’s Oath and (Sect. 45(1) (c) Wills Act or Sect. 19 (1) (c) Intestates Act). J. LIABILITY OF PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVES (i) Assets in His Hands The liability of Personal Representatives is generally limited to the assets which have come into his hands or the hands of another person for whom he is responsible. He can escape liability for these assets only by showing that he has duly administered them or by proving that they have been lost without his fault. He is not liable if the goods of the deceased are stolen without his fault or if they are perishable they become bad. He is not liable when he acts under an Order of Court. (ii) Devastavit Where the loss is due to some neglect or mistake of the Personal Representative even on a point of law, he is liable. Where he is negligent or makes a mistake on a point of law, he is said to have committed a devastavit as where he distributes the residue of an estate on a wrong principal of the law or if he were to pay legacies without retaining enough assets to meet debts. He is required to perform his duties exacta diligentia or with the utmost diligence. As long as a Personal Representative takes care of the estate and the duties of his office as any ordinary prudent person would with regard to his own assets, he is not likely to get into trouble. (iii) Assets not in His Hands There are two exceptions to rule that a Personal Representative’s liability is limited to assets which came into his hands: (a) Debts owed by the Personal Representative Page 47 of 105 A debt owed by the Personal Representative is an asset of the estate in his hands. It did not come into his hands as a Personal Representative but during the life time of the deceased as a debtor. (b) Willful Default A Personal Representative will be liable not only for what he received but also for what he could have received if he had not been negligent or careless. PART II PROBATE OR TESTAMENTARY SUCCESSION THE WILL 1. WHAT IS A WILL? A Will is a document in writing (containing instructions), or subject as mentioned later, which is properly executed as such in accordance with the internal law of the country in which it was executed or in which the Testator was domiciled or habituary resident or of which he was a national either at the date of the execution of the Will or at the date of his death (Sec 7(1) Wills Act). A Will executed on an aircraft or a ship is Page 48 of 105 executed in the country where the aircraft or ship belongs. (Sec 7(2) (a) Wills Act). Presumably an international train or bus when in a country other than its own would also represent the country to which it is closely related. The country of domicile is a country that the deceased considered his home. In this country a Will is properly executed if it is so done in accordance with section 6 of the Wills Act which repealed in Zambia the English Wills Act of 1837 which applied to Zambia until its repeal. Section 6 of the Wills Act states that: (1) A Will shall be valid if it is in writing; and (a) is signed at the foot or end by the testator or by some other person in the testator’s presence and by his direction; and (b) the signature referred to in (a) is made or acknowledged by the testator in the presence of two witnesses present at the same time who have also signed at the foot or end of the Will. By way of comparison the English Wills Act 1837, which still applies in Zambia for deaths of persons domiciled in Zambia occurring prior to the enactment of the Wills Act, has a similar provision in Section 9. (a) A Will shall be Valid if it is in Writing Any written document duly executed in accordance with the requirements of the law, relating to Wills which appears on the face of it or by some extrinsic evidence that it was the intention of the writer to confer benefits by it which would be conferred by it if considered to be a Will and if death was the event to give effect to it will be accepted as a Will. In a reported case in the Goods of Slinn (1890) 15 P.D. 156, probate was granted to a Deed Poll (document signed under seal by one party) which was duly executed and attested by two witnesses but contained no reference to the death of the testatrix. Evidence was admitted showing that she had intended it to be a Will. It also seems Page 49 of 105 that any form of writing, printing, typewriting or manuscript or a combination of these will do. In the Goods of S.S. Moore (1892) P.378 a testatrix by her Will made her illegitimate son her universal legatee with one of her executors. After the execution of the Will and shortly before her death, she expressed a wish to bequeath part of her furniture and other personal effects to her sister, her only next of kin, and proceeded to write out a bequest giving effect to such wish on a printed form of a Will and which was properly executed. The form commenced with a clause of revocation, but the testatrix did not fill up the blanks in this part of the form, and the clause was not read over to her at the time of execution, though the rest of the Will was read and there was no evidence that she knew of such clause. It was held that probate might be granted to the paper, omitting the revocation clause as a codicil to the original Will. The law does not specify any form of wording and it seems all that is required is an intelligible document which shows an intention to make a Will (see in Goods of Slinn above). (b) The Will must be signed at the foot or end thereof by the testator or by some other person in the testator’s presence and by his direction. [Section 6(1)(a)] (i) The Testator’s signature may be made in any way provided there is an intention to execute the Will. Initials, stamped name, thumb print (even when testator can write) former and assumed names and even an incomplete name have all been held in reported cases to be acceptable. In Baker v. William Denning (1838) 8.A & E.94 a mark was held to be good and that it was not necessary to prove that the testator could write his name at the time. (ii) Similar principles apply to a signature by someone on behalf of the testator, but it is important and absolutely necessary that when someone signs on behalf of the testator the signature must be made in the presence of the testator and that it must be authorized by him expressly or by implication. (c) The signature must be at the “foot or end” of the Will. (See above). Page 50 of 105 The effect of this requirement is that it must be apparent from the face of the Will that the testator by his signature intended to give effect to the whole Will (Wills Amendment Act 1852). There could be a blank space between what appears to be the end of a Will and a signature or the signature could even be on the next but otherwise blank sheet of paper. [In the Estate of Little (1960) 1.W.L. R. 495 a draft Will consisting of four sheets of paper and a back sheet all stapled together were sent to the deceased by his solicitor. The evidence as to attestation was that on a particular day, the deceased placed a number of apparently unattached sheets of paper on a table with the reverse of the back sheet on top, wrote his own name some eight inches down the page and caused the attesting witnesses to sign beneath his. On the death of the deceased the will was retrieved from deposit in a bank stapled together in the manner it had been dispatched from the solicitor but containing on the upper part of the back sheet above the signatures a handwritten disposition of certain specific chattels to the daughter of the deceased. The word “Draft” on the face of the back sheet preceding the word “Will” had been struck out. On an action by the executor praying for the Will to be admitted to probate which was defended on the ground of lack of due execution, it was held that even if there was no mechanical attachment of the separate sheets of paper at the time of execution the pressing of the sheets together by the deceased constituted sufficient nexus to produce a single Will.] However, nothing inserted after the Will was signed or which follows the signature will be admitted to probate, such as a sentence that begins on the signed page but ends on an unsigned page (See Practice Direction [1953] 1W.L.R.689), unless it is incorporated by some words above the signature such as “see other side for completion”. (See Palin v. Ponting (1930) P.185) In that case a Will made on a printed form was signed by the testatrix and the witnesses at the foot of the first page. In the margin above the signatures appeared the Page 51 of 105 words “see other side for completion”. On the back and under the words “continuation from other side” appeared further dispositions and a residuary clause. There was evidence that all these words were written before the Will was signed. It was held that the words on the other side must be included in the probate. (d) The signature of the testator must be made or acknowledged in the presence of two witnesses present at the same time. [See Section 6(1)(b)]. The Section does not state that the witnesses must be present when the testator signs but gives an alternative that they must both be present at the same time either when the testator signs or when he makes a proper acknowledgement of the signature as his, whether his own or that of someone else on his behalf and by his direction. A person may sign his will at any time even when he is alone, or someone may sign on his behalf in his presence and by his direction i.e. when they are only the two but, what is important is that he must subsequently acknowledge or confirm the signature to be his in the presence, both physically and mentally, of two witnesses who must be present at the same time and who must thereafter also sign in his presence. When a person signs his will in the presence of two witnesses who also sign in his presence there should be no problem. A difficulty arises when a testator signs before the witnesses arrive or when he signs in such a way that even if the two witnesses may have been present in the room with the testator and even if they had looked they could not have seen him sign. In such a case, it is necessary to show that the testator did in some way acknowledge that the signature was his own. See Morrit v. Douglas and Inglesant v. Inglesant 1872 3P & P172 It is important that the witnesses must see or should have been able to see had they looked what they were witnessing and that they must know that they are attesting something. It seems, however, that it is not necessary for the witnesses to know the nature of the document that they attest. (See Daintree v. Fasulo (1888) 13 P.D.102). In that case the testatrix exhibited a codicil to her last Will, written in her own handwriting, to one of the attesting witnesses, telling the witness that she had something which required two witnesses. When the second witness came into the Page 52 of 105 room she was asked to sign and the two witnesses both signed but the testatrix did not tell the witnesses what sort of paper they had attested. The witnesses did not recollect the testatrix sign but one of them was clear that her signature was there when they signed. It was held that the fact that the testatrix said she had something which required two witnesses was sufficient acknowledgement. In another case, Pearson v. Pearson [(1871) L.R.2P. & D.451 the deceased called a man who was illiterate to his room and asked the man to make his mark to a paper, which he did. At the deceased’s desire, the illiterate man fetched his wife who was living in the house and also illiterate. At the request of the deceased she also placed her mark on the same paper. There was no evidence the deceased’s signature was on the paper at the time the marks were made nor did the deceased in any way explain to the witnesses the nature of the document they had made their marks on. It was held that the execution was not valid as the witnesses did not know the deceased’s name or signature were on that paper before they made their marks as they could not read. If a Will is signed in the absence of witnesses, it is important that the witnesses see the signature or be in a position to see either the whole of the signature or a part of it. If they do not see, it is immaterial whether the signature was there or not the execution is bad. It follows that a blind person cannot be a witness to a Will, and so is a person non compos mentis. (See section 6(2)). It is also important that in acknowledging a signature, the testator must do so himself and not through a third party and that both witnesses must be present at the time the acknowledgement is made. But see Morrit v. Douglas and Inglesant v. Inglesant 1872 3P & D1 & 172 - In that case a witness was called into the deceased’s room and asked by a third party who had the Will in his hand to witness the deceased’s signature. The other witness was already in the room. There was a mark already on the Will. The two witnesses signed their names. The deceased was present and within hearing, but did not say anything. One of the two witnesses had died at the time the matter came into Court and the third party who invited Page 53 of 105 the witnesses to attest was not called upon to give evidence in court or to connect the Will to the deceased. The Court held that, as no evidence was produced to show that the deceased knew what was happening, there was no acknowledgement by him in the presence of two witnesses. But contrast Inglesant v Inglesant 1872 3P & D 172 -In that case at the request of the deceased, a third party called two witnesses in the room where the deceased was. One witness arrived first and the deceased signed the Will in the presence of the first witness. When the second witness arrived in the room, the third party asked the second witness to sign under the deceased’s signature. The two witnesses both signed. The deceased was present in the room but said nothing as the witnesses were signing. The Will was lying open on the table in full view of the witnesses. Held the deceased acknowledged her signature in the presence of two witnesses. (e) The witnesses must also sign at the foot or end of the Will. See Section 6(i) (b). Although the Act seems silent, both witnesses must sign in the presence of the testator and after the testator has signed or acknowledged his signature. It is his signature that they are witnessing or the fact that he has signed which they are attesting to. The testator must be physically and mentally present when the witnesses sign but in a reported case (In the goods of Chalcraft [1948] P.222) the testatrix lost consciousness after signing and during attestation. The execution was held to have been valid. It is sufficient that the testator knew that the witnesses were signing or that he could have seen them sign had he looked or if he had not been blind. The witnesses must sign and cannot acknowledge their signatures as the law does not make such allowance for them. See Wyatt v. Berry (1893) P.5) In that case the two attesting witnesses were father and son, both working at the same workshop but on different floors. The testator produced his Will first to the father alone and telling him it was his Will and asked him to witness his signature. The testator‘s signature was already on the Will and the father signed it. The testator then asked that the son who was working on the floor below be asked to come in and also Page 54 of 105 witness the Will. When the son had come and in answer to a question, the testator said he was ordering his affairs and that he had signed it. The son then signed it, all three being present. It was held the execution was not valid. There being no signature by two witnesses after acknowledgement by the testator. While the law appears silent on the matter, it seems it is strictly not necessary for the witnesses to sign in each other’s presence. The law stresses that the testator must sign or acknowledge his signature in the presence of both witnesses present at the same time, so that if a testator were to sign or acknowledge his signature according to the law and the first witness signs in the testator’s presence and then leaves the room while the other witness signs also in the testator’s presence, the execution will be good. However, in practice it is highly advisable that they should sign in each other’s presence. When applying for a grant of probate it should be remembered that it is important to show that the Will is valid. This is satisfied when it is shown on the Will that a testator and two witnesses signed. However, Section 6(1) requires that the signatures of the testator and his witnesses are made or appended in a particular manner i.e. testator must sign or acknowledge his signature in the presence of two witnesses, who must be present at the same time. The court will not grant probate to a will unless or until it is satisfied that the signatures were put on the Will in accordance with Section 6(1). For this reason, it is usual to have a Clause at the end of the Will indicating how the Will was signed. The clause will in effect state that the Testator signed in the presence of the two witnesses present at the same time and that the witnesses themselves signed in the presence of the testator. This is called the “Attestation Clause”. The Clause is not necessary to make the Will valid, but it is necessary to facilitate a grant as the Court requires knowing that the signatures which appear on a Will were put there in the correct sequence or manner. When this clause is missing, from a Will or for some reason it is considered defective in material particulars or insufficient, proof of the execution of the will in accordance Page 55 of 105 with section 6(1) must be given. Normally, when the will has an Attestation clause which shows that the Testator has signed in the presence of two attesting witnesses, all three being present together and that each witness signed in the presence of the Testator no further evidence of due execution is called for. The court will not look further but when the clause is missing or if the clause does not establish beyond doubt that the Testator signed in the presence of two witnesses and that they both signed in his presence or the Registrar of the probate court is in some doubt about due execution an explanation of what had happened is always necessary and this is done through an affidavit of due execution. The Attestation clause must establish beyond doubt what had happened even if it can only be inferred from other words in it that the Testator signed in the presence of two witnesses. A normal attestation clause will read on the lines as follows: “Signed by the Testator the said XYZ for and as his last will and testament in the presence of us both present at the same time who at his request and in his presence and in the presence of each other have hereunto subscribed our names as witnesses” When this clause is missing on a will, the will is valid if the necessary number of witnesses are present, but an affidavit of due execution is always necessary. The affidavit of due execution is made by either a) An attesting witness(s) or b) a third party who was present when the will was being signed. 2. WHO MAY MAKE A WILL? 1. A Minor or person of unsound mind Subject to section 6(3) any person who is not a minor and is of sound mind may make a Will [section 4 of the WA]. The WA defines a minor as a person who has not yet attained the age of 18 years. So, it would appear that any person above the age of 18 and is of sound mind may make a valid will. The Act does not define “sound mind” but it would seem that a person must not only be of sound mind; he must also have a good memory and able to understand what he is doing at the material time. When he is in an incapable state to understand what he Page 56 of 105 is doing he may not be able to make a valid will. The incapacity may arise from idiocy or general insanity but there may be some other reason or disorder of mind to render a will made under such circumstances invalid. One example is when a person is too drunk to understand or appreciate what he is doing or be under the influence of drugs or when as a result of severe illness, one’s memory is lost. The general test is whether at the material time a person was a) Able to understand the nature of what he was doing and its effects b) Able to understand and appreciate the extent of the property he is disposing c) Able to appreciate the claims to which he ought to give effect A delusion which affects the dispositions in a will has the effect of making a will invalid but if the delusion has no effect on the dispositions in a will, the will should be valid. The material time is when a person signs the will . This is so even when a person who is usually of unsound mind makes a will during a lucid moment or gives clear instructions to a lawyer but subsequently becomes too ill to appreciate what is happening a will has been held to be invalid. 2. A Blind or Illiterate person A blind or illiterate person can make a will. Section 6(3) of the WA requires that some independent person reads the will to the blind or illiterate testator explaining the full meaning and implications of the provisions of a will and gets the blind or the illiterate to indicate that he understands and approves the contents of the will and the person reading the will must in writing confirm that this was done before the will was signed. This is because a testator must have the animus testandi at the time he executes his will. This normally done in the attestation clause which must show that the requirements of section 6(3) where complied with and is very important because if it’s not done, the will is not valid. 3. Military/Security personnel/Terminally Ill person A soldier on active military services or a member of the security forces on active security operations or a person so terminally ill that he has lost all hope of recovery Page 57 of 105 and dies from that illness may all make valid wills without following the requirements of section 6(1) [section 6(4)]. They may make a will which is a) Written and unattested if it is signed and written by the testator himself b) If it is written irrespective of who writes it but attested by one witness or c) It can be oral but in the presence of two witnesses This is sometimes called “a privileged will”. The expressions “soldier” and “member of the security forces” when in active duty may extend to persons who are not strictly soldiers or members of the security forces but could include persons who provide supportive services to such military or security personnel such as drivers, nurses, doctors and even pastors or chaplains. It seems a privileged will made in these circumstances remains valid until revoked either in the same informal manner during such active service or hopelessness during illness. After the hostilities or when active service is over a formal revocation is necessary. The expression “active military service” means in connection with actual hostilities whether past or present or believes to be imminent in the future. A soldier is deemed to be in active military service in accordance with the provisions of the wills Act from the moment that he receives his mobilisation orders. Example: In Re Wingham deceased [1949] Probate Division 187 – in this case an airman who had entered the Royal air force (RAF) in the time of war was sent to Canada for training as a pilot. While there, he wrote what he called a will, signed it, but it was not attested. He died there from injuries received in an aircraft accident. The court held that the paper must be admitted to probate as a will as he was in “active military service” according to the law. The reason behind the privilege for soldiers on active military service or security personnel on active security operations and a terminally sick seems to be the fact that professional or proper help may not be readily available from this class of people to make formal wills and even if formally available, death could overtake before the normal formalities are completed. It is important to note that privilege is only available when a soldier is on active military service or a security personnel is in active security operations. Page 58 of 105 But a will made during the subsistence of such privilege will remain valid once made until revoked somehow. It would appear that during the existence of the circumstances that bring about a privilege an informal will can be revoked informally since the privilege is still available. However, after the circumstances which gave rise to the privilege cease to exist, the privilege of making informal wills also ceases and so does the privilege to of revoking wills informally. Any revocation thereafter must be made by formal means. The law does not define a soldier by age and it seems that a soldier who is a baby or a security personnel who is an infant or a terminally ill person who is a minor may make an informal will because of the privilege. Once the privilege has ceased, the soldier, security personnel or a terminally ill person can no longer make such will. A will made afterwards must be made formally in accordance with section 6(1) of the WA. An informal revocation is no longer possible once the circumstances giving rise to the privilege have ceased and since an infant does not qualify to make a valid formal will he may not also revoke a valid will during infancy. He has to grow up first to be able to revoke or he must start a war. However, we seem to have a problem with the terminally ill persons. The section requires that for a terminally ill person to qualify to make an informal will he must a) Be so terminally ill that he has a settled or hopeless expectational death b) Must have abandoned all hope of recovering and c) Must eventually die from that illness or injury It would appear that if the terminally ill person recovers from that illness and dies from another cause, the informal Will should not be effective. This should also mean that the informal Will of a terminally ill person is really a conditional will so that if he does not die from that illness, one of the conditions has not been met and therefore of no effect unless the requirements of section 6(1) of the WA have also been met. It would also appear that the Will of a terminally ill person should not be able to revoke a prior will until it actually becomes effective by the testator dying from that illness. Page 59 of 105 3. WHO MAY BE A WITNESS TO A WILL? a) Section 6(2) of the WA states that any person who is not blind and is of sound mind may be a witness to a will. i) The law clearly states that a blind person cannot be a witness because the signing of a will is a visible matter and a witness is required to actually see a signature of a testator and one who cannot see will not qualify. The law also says a person non compos mentis cannot be a witness because a witness must be present both physically and mentally when a will is being signed. An insane person would not normally know what is happening around him and is therefore not present in that sense. A person who is drunk is while in that state as good as a person non compos mentis and it is not advisable for such a person to be a witness. ii) Very young persons and illiterate ones while competent are to be avoided if possible. The young and illiterate may not understand what is happening unless what they are doing is clearly explained to them. They need to see the testator make his signature and not when he is writing just anything, or they must see the signature and not just anything written. There could be a problem if it became necessary for them to give evidence in court as a court might not give enough weight to evidence from such witness. Example of Pearson v Pearson - involving people who were not able to read where the court refused to presume that the witnesses saw the deceased’s signature. iii) Persons interested under a will are competent to be admitted as witnesses to prove the validity of a will but: a) Section 6(5) of the WA states that “any beneficial disposition of or affecting any property other than charges or directions for the payment of any debt given by the will made under this subsection to a witness to that will shall be void unless the will is duly executed (if written) or witnessed (if oral) by someone other than the beneficiary witness” b) Section 8 of the WA states that “a beneficiary who witnessed the execution of a Will shall lose his gift under a will other than any charges or debt directed by the will to be paid provided that Page 60 of 105 a) A beneficiary shall be competent to be admitted as a witness to prove the execution of that will or its validity b) A beneficiary shall not lose his gift under a will by reason that he witnessed a codicil confirming the will; and c) A witness shall not lose his gift under this section if there are at least two other witnesses who attested the will who are not beneficiaries under a Will and the Will is otherwise duly executed. Both Sections appear to apply to beneficial gifts by will so that a gift to Mr. A as a trustee for someone else and Mr. A witnesses the will, the gift should not fail since it is not really Mr. A who will benefit from the will. However, if the trustee has some other benefit because of being appointed, such as a lawyer who is also a trustee and is acting in the administration of the deceased’s estate, he cannot charge for his services. An attesting witness should not lose his benefit under a will if a will contains a clause allowing trustees to be remunerated if his appointment as trustee is not made by the will but arises after the testator’s death. E.g. where a nun in a convent by her will gave all her property to the person who at the date of her death would be or act as the head of that convent. The court construed that as gift to the head of the convent as a trustee for the convent and the gift was held valid although the person who had become head of the convent at the time of the testatrix’s death was an attesting witness to the will (see Rays Will Trusts v. Berry (1936) Ch. 520). This will be so even where a beneficiary under a will marries an attesting witness long after the Will was executed. The disqualification must exist at the time of attesting. The sections apply to gifts made by the will. A gift to A, who has a separate agreement with the testator that he will hold the gift for B and, Page 61 of 105 B attests the will. The gift will not fail because B does not get the gift from the Will but from the separate agreement between the testator and A, who was not a witness to the will. The sections should not affect a gift made by will if the witness attests a codicil confirming it even if the codicil increases the gift thereby, such as by revoking one gift and increasing the residue of the estate to which the witness is entitled. It also seems that a gift in a will to a witness will be valid if confirmed by a codicil or other testamentary instrument which he does not witness. This would appear to be the case even where a witness attests a Will giving a legacy to him and attests one of two codicils confirming the Will (see Trotter v. Trotter (1899 1Ch.764 - In that case Charles Trotter appointed by his Will John Trotter a solicitor, one of his executors and trustees and directed that his trustee John Trotter notwithstanding his acceptance of the appointment as trustee should be allowed all professional and other charges for his time and trouble. John Trotter was one of the attesting witnesses. Subsequently the testator made a codicil to his will making an additional bequest to a niece. John Trotter did not attest the codicil. However, later the same year another codicil was made in which some alterations were made to the gifts in the will. The solicitor attested this codicil. It was held that as the will was confirmed by the 1st codicil, not attested by John Trotter, his attestation of the second codicil did not affect the gift as already confirmed. See also in Re-Pooley (1888) 40 Ch.1 - In this case Ms Solomon died in July 1887 leaving a Will, by which she appointed Brown and Pooley the executors and trustees of her estate. Mr. Pooley was a solicitor. The Will contained a clause that any trustee of her Will who should be a solicitor should be entitled to charge for all business done in relation to the estate as if he had been a solicitor employed by the trustees. Mr. P. was one of the attesting witnesses. Held Mr. P. was not entitled to any profit costs for business done by him in relation to the estate, for the right to make professional charges could, only be claimed under the Will, as a Page 62 of 105 beneficial interest under it and was prohibited by Sect.15 of Wills Act 1837 (read Sect.8). It seems the section should not affect a gift in a privileged will which does not require a witness so that a witness to such privileged will should not lose his gift if the Will does not require a witness. But see Sect. 6(5) and section 8 above. A gift to three joint tenants one of who witnesses the will benefits the other two who were not witnesses as if the witness had died and the jus accrescendi applied. This also applies to gifts made to a class of people such as children or workers. The one who attests drops out, but the others will share the whole property. A gift to three tenants in common, and one of them attests a will results in two of them receiving their one third share each and the witness’s share falls into residue as a failed gift. A witness whose spouse is a beneficiary under a will might also render such gift void for the spouse, so care must be taken. 4. INCORPORATION OF DOCUMENTS Document and other written instruments which are not themselves signed in accordance with the requirements of section 6(1) and which may not even be testamentary dispositions may be incorporated in Wills if such documents and instruments are in existence at the date of the Will and are sufficiently identified by the Will [section 14 WA]. It is important to note that for a document or other written instrument to be incorporated into a will and be entitled to be admitted to probate it must: (a) Be in existence at the date of the execution of a will; (b) Be referred to by the Will as being in existence as oral evidence to prove its existence will not be admitted; Page 63 of 105 (c) Be distinctly referred to in the will and be clearly identified by the will or the will must refer to it in such a way that it is possible to identify if beyond all doubt by oral evidence. It seems that a document not in existence at the date of the execution of a will but in existence at the date of the execution of a codicil confirming the will, will be incorporated and so be entitled to probate provided the will itself speaks of it as existing. In the case of Lady Truro, ((1866) 1P. & D.201), Lady Truro died on the 21st day of May 1866 leaving a will dated the 15th September 1865 and a codicil dated 10th October the same year. The will contained the following clauses: “I bequeath to……….…… such articles of silver plate and plated articles as are contained in the inventory signed by me and deposited herewith” The will was deposited with Bankers and in the envelope in which the will was found was an inner envelope containing a list of plate. The list was headed: “List of Plate or Plated Articles left by my will dated the 15th September 1865.” On the last page of the list was the deceased’s signature and dated 21st September 1865. Evidence showed that the will was deposited with the bankers on the 21st September 1865. It was held that as the will spoke of the list as existing and as it was in existence on the 10th October 1865, the date of the codicil, the list must be admitted to probate. Contrast in the goods of M. Sunderland (1868) 1P. & D. 198 The testatrix by her will bequeathed the residue of her estate, save and except such articles of “furniture as shall be described in a paper in my own handwriting to show my intention regarding the same.” When she gave instructions to her lawyer, she produced two lists which she said was the paper she intended to refer to. When the will was executed, the witnesses did not see the list but when a second codicil to the will was Page 64 of 105 executed, the attesting witnesses saw a list, but the testatrix did not make any verbal reference to it. It was held that as the will did not describe the list as then existing oral evidence was not admissible to prove its existence and must be excluded from probate. In a case where a testator gave money to found a scholarship on the terms “specified in any memorandum amongst my papers written or signed by me relating thereto,” it was held the word “any” made identification difficult and a document existing at the date of a will was refused probate. (See University College of North Wales v Taylor 1908 P.140) 5. ALTERATION TO WILLS Section 12 of the Wills Act provides that: “No erasure, interlineations or other alteration made in a will after its execution shall have any effect unless that erasure, interlineations or other alternation is: a) signed in accordance with Section 6(1) by the testator and the witnesses in the margin or some other part of the will opposite or near the alteration; or b) referred to in a memorandum written at the end or some other part of the will and the memorandum is signed by the testator and the witnesses in accordance with the provisions of section 6(1).” Once a person is dead, that person remains dead irrespective of what anyone else would want. Any changes to a will must therefore be made or acknowledged by the testator before he dies in the same way he executes his will, i.e. he signs or acknowledges a signature as his in the presence of two witnesses present at the same time and who must attest. If the alteration is not properly signed for, it has no effect at all and probate will be granted to the will as it originally was even if it becomes necessary to Page 65 of 105 call evidence to show what the will provided before the alteration but a court will not interfere with the physical appearance of a will so that if a testator pasted a piece of paper over part of the will, probate will be granted to the whole will, with the exception of that part which was pasted over. When an alteration appears in a will and if the alteration is not attested in accordance with the requirements of the law, it is presumed that it must have been made after the will was executed. It is up to the party who derives a benefit from the alteration to prove when it was made. However, declarations made by a testator before signing of the will have been admitted showing that the testator’s intentions could not be carried out without the alterations having been made. Copies of a will made before execution and showing the alterations would be admissible to prove that the alterations were made prior to execution. Authority is The Estate of Oaths, Callow v Sutton 1946 OER PG 735. The effect of an unattested alteration is that if it is possible to read the original wording, the alteration is simply ignored. If it is not possible to read the original wording even after calling for evidence, then the alteration is treated as a destruction or revocation of that part of the will but only to the extent of the unattested and illegible alteration or obliteration. In the Goods of Heath (1892) Probate p.253 case a testator by his will gave 10,000.00 Pounds Sterling to A, one of his executors and after execution of the will he made an interlineation giving 1,000.00 Pounds Sterling to each of his executors. The interlineation was not attested but in a subsequent codicil, he indicated that he had given A the sum of 11,000.00 Pounds Sterling. It was held that the interlineation must be admitted to probate, the codicil operating as confirming the will with the alteration. In the Goods of Shearn (1880) 50 The Law Journal p.15 case, a testatrix executed her will according to the law but immediately discovered an omission which was rectified immediately by an interlineation. The testatrix then approved the will as altered and declared it “her last will and testament” and Page 66 of 105 the witnesses in her presence placed their initials in the margin opposite the interlineations. The court refused to accept the interlineations as not properly executed in accordance with the law. The testatrix should have signed or put her initials first and then the witnesses should have thereafter put their signatures or initials. In the Estate of Hamer (1944) T.L.R. 168 a will as executed contained a legacy to A of “the sum of two hundred and fifty pounds”. Subsequently the testator rubbed out the words “two hundred and” without executing the alterations. It was held that this operated as a destruction of the will to the extent of the obliteration. Probate was granted to the will with a blank space between “the sum of” and “fifty pounds.” Alterations made before execution must be attested in accordance with Section 6(1) or evidence produced by the affidavit of one of the attesting witnesses or someone else present when the will was executed as to the existence of the alterations at execution otherwise they are of no effect. A will must not be defaced in any way, and if it becomes defaced, an explanation must be made by affidavit. This is called an affidavit of plight and condition. Alterations made after execution will be excluded unless they are attested in accordance with section 6(1) or confirmed by a properly executed codicil or other memorandum or instrument executed in accordance with section 6(1). It seems alterations in soldiers or other person’s privileged will are not affected unless it can be proved that the alterations were made after the privilege had ceased to exist. 6. WHEN IS A WILL IS NOT A WILL? I. A will which meets all the requirements of Section 6(i)(a) and (b), or Section 6(4) may still not be a good will. A testator must execute a will with the intention that it is his will. The intention to make a will or animus testandi must be present. If the intention is not there as for instance when signed as a joke or under a mistaken belief that it was Page 67 of 105 another one, then the will must fail since it is essential that testator must both know and approve of its contents. In the Goods of Hunt (1875) L.R. 3P. & D.250) case, the deceased who lived with her sister prepared two wills to be signed by each of the sisters respectively. The legacies in each and the disposition of the residue were almost identical and in either case a life interest was given to the survivor in bulk of her sister’s property. The deceased by mistake executed the will prepared for her sister. It was held that the deceased did not know and approve the contents of the documents she executed, and probate was refused. In the Estate of F.D. Meyer (1908) P.353 two sisters executed codicils similar in terms. By mistake each sister executed the codicil intended for and purporting to be that of the other. Upon application after the death of one of the sisters for probate of the codicil executed by her, it was held that as the intention to execute the document produced to court was absent probate must be refused. II. However, if it is shown, the testator knew the contents of his will, nothing can be added or omitted after his death on the ground of mistake. His execution of the will is sufficient proof of knowledge and approval of the contents except where there is some suspicion concerning the document. In Collins v. Elstone (1893) Probate p.1, a testatrix left two Wills and a codicil to the first will. The second Will which disposed only a small insurance policy on her life was prepared for her on a printed form by one of her executors. The form commenced with a clause revoking all former wills, but when this was read to her she immediately objected to its saying she did not want to revoke her first will and codicil. The person who prepared the will assured her that as it only related to the insurance policy the revocation would not apply to her former will and codicil and that an erasure might invalidate the new will. On this assurance, she signed the will. It was held that the testatrix knew and Page 68 of 105 approved the words. The mistake of her agent was deemed to have been her mistake. The first will and codicil were effectively revoked and could not be admitted to probate. III. It is important that a testator executes his will without force fear or fraud since if he signs under these circumstances it is not really his intention to sign or it is not his will at all. A will executed at gun point or in a situation where the testator has a reasonable fear of death, injury or some other fear at the hands of another person, the Will, is not valid as the animo testandi is missing and therefore not really the testator’s will. Similarly, a will obtained by fraud will not be valid for lack of the intention to make a will. IV. A will secured by some undue influence by one person over another will also render a will invalid. The real intention to make that particular will and in that manner by the testator being absent. What amounts to undue influence in a particular case will depend on the circumstances of that case. V. A mere honest pleading or persuasion may be used to procure a will in favor of oneself or another without disturbing the validity of a will. However, if the persuasion is to someone whose mental capacity has been weakened by disease or illness such as on a death-bed, the intention to make that particular will and in that manner may be missing thereby invalidating the will. It is possible for one person to acquire influence or dominion over another person so as to prevent such other person from exercising his own discretion. Such influence or dominion could amount to undue influence so as to invalidate a will. The influence must however relate to the will itself and not to other matters. It has to be the testator’s free wish to make a will and in a particular manner and if such wish is absent, then it is not his Will. 7. REVOCATION OF A WILL Page 69 of 105 A will has no effect at all and is useless to any one until the testator has died. Until the death of a testator, a will operates merely as a declaration of his intention and as with any intention, it can be changed from time to time. A will “wakes up” or “comes alive” only when a testator has died and starts to speak then. It is therefore said to speak from death. Despite any declarations in a will or any other document, a will can be revoked any time while the testator is alive. A contract not to revoke a will is binding but it does not prevent its revocation although it gives a right of action for damages against a testator’s estate if it is revoked. See (In the estate of Mary Heys (1914) P.192.) In that case both husband and wife executed Mutual Wills in 1907 arranging clearly between them that the Wills were to be irrevocable. In 1911 the husband died and his Will was proved. In 1912 the widow executed a codicil to her Will and 1913 she executed a fresh Will. The codicil and fresh Will were executed in breach of the arrangement between herself and her husband in 1907. It was held that the 1907 Will was revocable and that the 1913 Will must prevail. A codicil is a testamentary document supplemental to a will and usually amends, varies, adds to or revokes provisions in a will. It is governed by the same rules as a will. If it is independent of a will, then it is a will. It has to supplement the “efforts” of the provisions of a will. However, while it is supplemental to a will, it can still remain effective on its own even when the will to which it is supplemental is revoked. In the case of the Goods of Savage (1870) Probate & Divorce p.78 John Savage died on 9th January 1870 leaving a duly executed testamentary paper which commenced “This is a codicil to my will” and proceeded to make dispositions of his property. The will was never found and evidence was produced to the effect that the original will had been burnt. It was held that the codicil was not revoked by revoking the original will. It needed to be revoked in accordance with the provisions of the Wills Act 1837. Page 70 of 105 In simple language the definition of a will would seem to be “A declaration of intention by a testator with regard to his property or assets which intention takes effect from the testator’s death.” This simple definition would appear to apply to a codicil which as we have seen, is subject to the same rules as those that apply to a will: 1. Section 13(1) of the Wills Act states that: “A will or any part of it may be revoked by: (a) A later will or codicil duly executed and expressed to revoke the earlier will. (b) A written declaration of intention to revoke, executed in the same manner as a will. (c) Burning, tearing or otherwise destroying the will by the testator or by someone in his presence and by his direction with the intention of revoking it.” A. By another Will or Codicil A revocation clause expressly revoking all former wills is effective provided it is contained in some document executed in accordance with Section 6(1) of the Wills Act. This would appear to be so even if the testator was misled as to the effect of the clause (see Collins v. Elstone [1893] P.1 above), but not if the testator did not know of the presence of the clause, (see in the Goods of Moore [1892] P.378) (above page 21). A will is not revoked merely because a later will states, “This is the last will of me” or even “Last and only Will”. In Simpson v. Foxon (1907) P.54 a testator executed a will in 1898 disposing of all his property and appointed his daughter executrix. In 1903 he executed a document on a printed form which commenced “This is the last and only will of me… “by which he disposed the proceeds of an insurance policy and appointed another executor. In 1905 he executed yet another document described as “a codicil to the last will” in which he made other dispositions and appointed other executors. It was held that the words “the last and only” Page 71 of 105 in the intermediate document did not preclude the admission to probate of all three documents. The later will must contain a revocation clause or it must show an intention on the part of the testator to revoke the former testamentary instrument. A soldier in actual military service and other persons who qualify to make privileged wills, may revoke a will even, a formal one by an informal will but only during the existence of the circumstances that give rise to the privilege and provided such informal will shows an intention to revoke the former will. In the Estate of Gossage (1921) P.194 A soldier on 24th October 1915 when under orders to proceed with his unit to South Africa after the outbreak of war, made his formal will in accordance with the Wills Act of 1837 whereby, inter alia, he gave the residue of his estate to the plaintiff who was then engaged to be married to him and appointed her, his sole executrix. He gave this will to her in a sealed envelope but indicated it contained his will but directed her not to open it unless something happened to him. After certain statements to the testator made by the plaintiff as to her conduct in his absence he wrote to her from South Africa, asking her to hand over the envelope to his sister which the plaintiff did. On the 9 January 1918, he wrote to his sister from Cape Town, asking her to burn his will as he had already cancelled it. The sister accordingly did as directed. In November 1918, the testator died in a South African hospital and among his belongings was found a copy of his will. In an action to establish the will by the former fiancé’, it was held that the letter of the 9th January 1918 (written during actual war) effectively revoked the will. An express revocation clause will have no effect if there is evidence from surrounding circumstances to show that the testator did not intend to revoke the former will or to revoke one will, for the purpose of making another will, which he does not in fact make. (See Dependent relative revocation later). For example, where the first will is expressed to deal with an estate in one country and the second one, containing an express revocation clause, is expressed to deal only with the estate in another country. Page 72 of 105 A will is revoked by implication if a later will is executed and merely repeats the former will or is inconsistent with it, but if the repetition or inconsistency is merely partial, those parts of the former will which are not repeated in a latter will or inconsistent with it remain effective. Any number of testamentary documents may be read together, each being effective except so far as subsequently varied or revoked and the sum total of those documents making up the testator’s will. It is not enough to show that a testator executed a subsequent will as this on its own will not revoke an earlier will. The contents of the subsequent will must be known and if they have to have an effect of revoking a will the contents must contain a revocation clause or dispositions contrary to or inconsistent with those contained in an earlier will. This will be the position where a later will is proved to have existed but cannot be found or evidence is available that the later will was destroyed. The contents must be known if it has to have an effect of revoking an earlier will. In the case of Re Howard 1944 CH p.39, a testator executed a Will in 1933 In the case of Re Howard 1944 CH p.39, a testator executed a Will in 1933 and on the 6th of May 1940, he executed two wills: one leaving all his estate to his wife; and the other leaving it to his son. There was nothing to show the order in which the two wills were executed, but each contained a clause expressly revoking all former wills. In the same year, all three were killed in an air raid. It was held that the two wills could not be reconciled to each other and so could not be admitted to probate. However, both were effective to revoke the 1933 will. B. By a Written Declaration A written declaration of intention to revoke a will or testamentary instrument does not need to be in a will or codicil. It can be in any document, instrument, or any writing even an ordinary letter. The important thing is that it must be Page 73 of 105 signed in accordance with the provisions of Section 6(1) or Section 6(4) of the Wills Act. In Spracklan’s Estate (1938) 2 ALL ER 345 a testatrix who had made a will about a month before her death and at a time when she was seriously ill, dictated a document which was duly executed in the manner that a will should be, containing the following words: “Will you please destroy the will already made out.” This document was addressed to the Manager of a bank in whose custody the will had been placed. It was held that the wording of the document showed a sufficient intention to revoke the will within the meaning of Section 20 of the Wills Act 1837. C. By Destruction A will is revoked by “burning tearing or otherwise destroying the will by the testator or by someone in his presence and by his direction with the intention of revoking it. There are two very important elements necessary in this case to effectively revoke a will. The act of destroying and, the intention to revoke or “Animus revocandi” (1) The Act of Destruction While it is not necessary that the will should be completely destroyed, it is important that there must be some burning, tearing or other destruction of the whole or some essential part of it such as the cutting off, obliterating the signature of the testator or the witnesses such that these cannot be read or seen at all. The will will no longer meet the provisions of Section 6(1). See in the Goods of H.G. Morton 1887 12 P & D 141 in which a will after execution had remained in the custody of the deceased (testatrix). After her death, the will was found among her belongings but with her signature and those of the attesting witnesses scratched out apparently with a knife. It was held that there was a revocation within the meaning of Section 20 of the Wills Act 1837. Drawing a line through the will is not enough unless the requirements for the execution of a will are complied with. Page 74 of 105 See Cheese v. Lovejoy (1877)2 P.D. 251. In that case the Testator drew a line through various parts of his Will and wrote on the back of it “This is revoked” and threw it among a heap of waste paper in the sitting room. A servant picked it up and put it on a table in the kitchen where it remained until the Testator’s death some eight years later. It was held that it was not revoked and was entitled to probate in spite of the Testator’s intention to revoke. Destruction of part of a will revokes that part only unless the destroyed part is so vital that the rest of the will cannot stand without it. (See in the Goods of Woodward (1871) 2 P & D 206. In that case on the death of the deceased, a Will was found in an iron chest where he kept important papers. The Will had been properly signed but the first 7 or 8 lines had been cut and torn off but in other respects the Will was complete. Held the Will must be admitted to probate in its incomplete state. The part that was cut off being deemed revoked. An unauthorized destruction cannot afterwards be ratified by the Testator - Gill v. Gill (below). The destruction of a will by someone else is not effective unless carried out in the presence of the testator and by his direction. In Gill v. Gill (1909) P.157 a drunken husband (testator) said something nasty to the wife who in fit of temper tore up the husband’s will. It was held that although the will was destroyed in the husband’s presence, he was so drunk that he could not have been capable of giving the authority and the wife was so angry as not to have been capable of appreciating what she was doing. The will was not revoked. If a will is destroyed without being revoked as where the intention to revoke is missing it can be proved by means of a draft or file copy or even by oral evidence (see Sect. 32 (1) of the Wills Act). (2) The Intention to Revoke A testator must have an intention to revoke a will at the time of destruction. If a will is unintentionally destroyed or torn by a testator who is drunk or who believes the will to be ineffective, the will is not revoked. Page 75 of 105 In the Goods of Brassington (1902) P.1, the testator in a drunken state went to a tin where he kept his papers and tore up his will. The following day, having sobered up, he put the pieces of the will together and pasted them to another paper. It was held that there was no intention to revoke and the will was admitted to probate. It is said that “All the destroying in the world without intention will not revoke a will or all the intention without destroying: There must be the two” (Lord Justice James in Cheese v. Lovejoy above). We have seen that the revocation of a will does not revoke a codicil to that will, (see the Goods of Savage (above)). Unless, of course, for some reason the will and codicil are contained on the same sheet of paper and the testator cuts off his signature to the will, but evidence will be necessary to show the testator’s actual intention. When there is more than one copy of a will executed, one copy being kept by the testator and another deposited elsewhere, the destruction by the testator of the copy in his possession with the intention of revoking, revokes all copies. Indeed, when a will is executed in more than one copy and one copy kept by the Testator or by his direction is never found after the death of a testator, the presumption is that the will was revoked. However, if the Testator had gone non compos mentis prior to his death the destruction will be presumed to have been done without the animus revocandi and therefore ineffective to revoke the missing Will. It is therefore dangerous or unwise to have a will executed in more than one copy. Section 13(1) of the Wills Act provides us with three methods of effectively revoking a Will. There is a fourth. Section 18 of the Wills Act 1837, which still applies to Zambia for Wills made or marriages taking place prior to 1989, provides in general that for all Wills made after 1925 a testator’s subsequent marriage revokes his or her Will. If a testator or testatrix married after executing a Will that marriage revoked all Page 76 of 105 earlier wills automatically. This is the second method of revoking a Will without the animus revocandi. There are two exceptions to Section 18 but we shall deal with only one: If a person made a Will and, in the Will, indicated that he was contemplating marrying a particular person, the marriage to that person did not revoke that Will. The person intended to be married must be identifiable from the Will. Dependent Relative Revocation If revocation is relative to another will and intended to be dependent on the validity of that will, the revocation is ineffective unless that will takes effect. This is the doctrine of dependent relative revocation. Mr. Justice Langton in The Goods of Hope Brown (1942) P.136 at page 138 made the following observation about the doctrine that the title was “somewhat overloaded with unnecessary polysyllables. The resounding adjectives add very little, as it seems to me, to any clear idea of what is meant. The whole matter can be quite simply expressed by using the word “conditional”. If a testator destroys his will with the intention of making, establishing, or reviving some other will or testamentary paper the revocation is not effective if that other will or testamentary paper is never made, established, or revived. Sometimes a testator would make a disposition different from one contained in an earlier will under a false impression of fact, and sometimes of law which induces him to change his earlier intention. If the fact or the law happens to be false, the will is not revoked. It was said in Re estate of Southerden (1925) P.177 that “A revocation grounded on an assumption of fact which is false takes effect unless, as a matter of construction, the truth of the fact is the condition of the revocation or in other words, unless the revocation is contingent upon the fact being true.” Page 77 of 105 In simple language, the doctrine is merely one of “conditional” revocation. When a revocation is done on condition that something else happens or takes effect, there is no revocation if the condition never materializes. There is no revocation if revocation is conditional on some fact or law being true and it turns out to be untrue. In the case of Southerden (above) the deceased, when preparing a trip from the UK to the USA with his wife prepared and executed a will leaving all his property to his wife if she survived him and left the same property to other people is she failed to survive him. Upon returning from the USA, he told his wife that as they had returned safely, the will was no longer necessary since everything would be hers upon his death. With his wife’s consent, he burnt the will. When the husband died, survived by the wife, the executors propounded the will but the father of the deceased (who would have benefited under intestacy) opposed. It was held that since the will was destroyed under the mistaken belief that the wife would inherit all his property on his intestacy, the will was not revoked. The case however, is always one of fact. What was the testator’s intention when revoking a will? Was it to achieve some effect which fail and if so, no revocation. The condition of revocation has not materialized. See Carey deceased (1977) 121 Solicitors Journal (SJ) 173. The Testator destroyed his Will believing that he had no assets to leave but had forgotten that he was entitled to inherit from his sister if she predeceased him which she did. It was held that the Will was not revoked although the Testator had revoked his will by destruction. See also Davies (1851) 1 ALL ER 920 where Testator destroyed the earlier Will believing the later Will was validly executed when it was not. Held, destroyed will was not revoked. Section 13(5) of our WA provides that the destruction of a will by the testator, a) As a result of fraud or undue influence: b) By accident; and, Page 78 of 105 c) Under a mistake of fact or law, does not revoke a will. 9. REVIVAL AND REPUBLICATION OF A WILL A. REVIVAL A Will which has been revoked or “killed” can be revived. However, a murdered person will not come back to life if you simply kill the murderer. Similarly, a revoked will does not get revived because the will or codicil revoking it has been itself revoked. Section 15(1) of the Wills Act, and see the case of Hodgkinson, below. There are two methods of bringing a will back to life or reviving it. These are: a) Re-executing (signing) the revoked will or revoked codicil, in accordance with Section 6(1) of the Wills Act, or b) Executing a codicil, in accordance with Section 6(1) but showing an intention to revive the “dead” will. The authority for the above is Section 15(2) of the Wills Act. (i) Revival by Re-execution The revoked will or codicil must be re-executed in exactly the same way as a new will i.e. Section 6(1). The will then comes “alive” or is revived at the date of the re-execution so that for certain purposes of construction, the Will is deemed to have been made at that time, Section 15(3). In the case of the Goods of Hodgkinson (1893) P. 339 a testator by his will gave all his property to A and afterwards made a second will giving all his real estate (immovables) to B but containing no revocation clause. He subsequently revoked the second will. It was held by the Court of Appeal that probate be granted to the first will but limited only to the personal estate (movable assets) since so far Page 79 of 105 as it concerned the real estate (immovable property), it had been revoked by the second will. (ii) Revival by Codicil A codicil can revive a revoked will if it not only expressly or impliedly refers to the revoked instrument but the intention to revive it must also be shown. The mere mention that a document is a codicil to a revoked will not do. The intention to revive must be shown. In the Goods of Davis (1952) P.279 a testator made a will in 1931 giving a property to Ms X whom he married about a year later. In 1943 upon hearing that his marriage had revoked his will, wrote on the outside of the envelope containing the will the words “The herein named X is now my lawfully wedded wife.” This was signed in accordance with ‘Section 6(1)’ of the Wills Act. It was held that the statement was a codicil reviving the will. But, merely attaching a codicil to a revoked will does not revive such Will unless the intention to revive is somehow evident as in the case above. In Re Pearson (1963) 3 ALL E.R. 763 Pearson in 1948 made a Will containing a clause revoking all prior wills. In 1956 he made another will containing a similar clause. In 1957 he made a codicil to the 1948 will. The codicil ended with the words “in all other respects, I confirm my said will.” It was held that the codicil revived the 1948 will including the revocation clause which effectively revoked the 1956 will. However, a will revoked by destruction animo revocandi can never be revived. The will to be revived must exist at the time of revival. B. REPUBLICATION Page 80 of 105 A Will which has never been revoked can be confirmed and thereby rejuvenated or given a fresh lease of life. A revoked Will cannot be confirmed or republished. It has to be revived first. A Will which has been effective all the time can, however, be confirmed. When a testator executes a Will, he is said to publish it or make it known to the people that he has a Will. Republishing is therefore merely publishing the same Will again or confirming the same old Will. This may be done in two ways: (a) Expressly by re-executing the Will at a later date, or (b) It may be impliedly confirmed or republished by subsequently executing a codicil to that Will. The effect of re-publication is as if a Will was made on day of republication but with the benefit of all variations or alterations made by intermediate and properly executed testamentary instruments. Unattested alterations made after the execution of a will become part of the will if it is later republished or confirmed by any of the two methods stated above. Republication will extend the operation of a will to property or persons to whom or to which the description is applicable at the date of republication. However, re-executing a Will which had not been revoked does not always have the effect of republication as where the testator had another reason for re-executing. See Dunn V Dunn 1866 1 P & D 277 where the testatrix had executed a Will in 1837 appointing her nephew as executor and giving him the residue of her estate. On the 20th May, 1861, as she wished to give the Will and title deeds to her property to her nephew for safe custody in the presence of a witness, she called a third person to be a witness to such delivery. Before delivery, she signed her name at the foot of the Will and both the nephew and the third person put their signatures and the nephew Page 81 of 105 indicating that he was (executor”). The testatrix did not give any reason for signing the Will again. Held Will signed only in 1837 – no republication. Confirmation by a Codicil does not always result in republication of a Will if the result is likely to go against a testator’s intention. 10. CAN A TESTAMENTRY DOCUMENT BE ALTERED AFTER TESTATOR’S DEATH? We have seen that a Will can be revoked at any time during the life time of a testator as long as he complies with the provisions of the law. We shall soon see that Courts will bend backwards to try to give a meaning to a testator’s intentions or wishes. We shall also see that under no circumstances will the courts re-write a Will. However, with this in mind, a testator or testatrix may have responsibilities to members of his family or those who may be dependent on him or her for their livelihood which may not necessarily terminate on his or her death. For this reason, while a testator or testatrix has freedom to express his or her wishes with regard to the disposal of his or her assets after death, the testator or testatrix must always bear in mind the responsibilities as breadwinner for the people who depend on them. As a result of the problems that sometimes befall a family after the death of a breadwinner, as where for example, whether for a good or bad reason a testator might give all his property to a mistress or a charity, the legislators introduced some method of indirectly restricting the freedom of a testator to dispose of their property as they liked. The Inheritance (Family Provisions) Act 1938 was introduced in Britain in July of that year for that purpose. This Act gave power to the Court to vary or modify within defined limits the Will of any testator who had failed to make Page 82 of 105 reasonable provision for the maintenance of a surviving spouse, an infant son or an unmarried daughter or a son or daughter who were incapable of maintaining themselves. This power was, by the Intestates Estates Act 1952, extended to apply to both total and partial intestacy. Our legislators have in Section 20 of the Wills Act introduced a similar method of dealing with those who make Wills and die domiciled in Zambia and, as in England, the proviso to Section 5 of our Intestate Succession Act Cap 59 has extended the application of the dependence provisions to total and partial intestacy. Section 20 provides as follows: (i) “If, upon application made by or on behalf of a dependent of the testator, the court is of the opinion that a testator has not made reasonable provision whether during his life time or by his Will, for the maintenance of the dependent and that hardship will thereby be caused, the Court may, taking into account all relevant circumstances and subject to such conditions and restrictions as the court may impose, notwithstanding the provisions of the Will, order that such reasonable provision as the court thinks fit shall be made out of the testator’s estate for the maintenance of that dependent.” The Section, like its English counterpart, does not require a person dying after 1989 domiciled in Zambia to make reasonable provision either during his life time or by his Will for the maintenance of his dependents. It merely empowers the court to interfere if the court concludes that the dispositions made in the Will were unwarranted. (See In Re Styler 1942 Ch. 387). In that case the testatrix after agreeing to make a Will in favor of her Husband left all her property to her daughter by her first husband leaving nothing for the second husband. On an application by the widower for reasonable provision, the court held that the law (Act) did not impose a duty on a testator to make reasonable provision for his Page 83 of 105 dependents but merely gave the court the right to interfere if it concluded that the dispositions which were made were unwarranted. Dependents are defined as “Spouse, Child or Parent”, and Child is defined as “including an illegitimate as well as an adopted child and a Child En Ventre Sa Mere (defined as “conceived at the date of the event and born alive in due course”). (Section 3 Wills Act). The law in England, which still applies to Zambia for deaths prior to 1989, did not include parents or illegitimate children. The Court will not make an order, however, if the dependent has or is likely in future to have adequate income from any other source or where the net estate is too small. The law or in our case, the Section was not made to provide a legacy to a dependent but merely to provide for maintenance from the income of the net estate. (See, the case of Vrint (1940) Ch.920). In that case by his Will the testator gave all his estate to A leaving nothing for his wife who was 58 years old. The widow was entitled to a widows’ pension and at the age of 60 she would also be entitled to an old age pension. Prior to the testator’s death the widow had asked for maintenance from the husband and he had given reasons why he did not want to comply. After his death the testator’s estate was found to be too small about 138 Pounds. In an application for maintenance by the widow, the court held that as the estate was too small and an application under the (law) could not be entertained. See also Diamond v. Standard Bank of South Africa 1965 ZLR 61. In that case the testator died leaving a Will appointing the Bank executor. In the will the testator gave a gift of 1,000.00 Pounds to his wife and the sum of 1,000.00 Pounds per year until her re-marriage or death. The residue of the estate was left to other beneficiaries. The net value of the residue was 800,000.00 Pounds. The testator left a letter with a friend where he was alleging infidelity on the part of the wife and gave this as the reason for the gifts to her in the Will. It was held that the reasons for the gifts made to the wife had not been proved therefore the gifts were unreasonable. Page 84 of 105 The 1,000 Pounds was increased to 1,950.00 Pounds and the annuity was increased to 2,950.00 Pounds. In relation to the meaning of the word “maintenance” Justice Hodson in Scott v Scott 1951 1 ALL ER 216 said “In my view, the question what reasonable maintenance for the wife and children is has to be considered with reference to the husband’s common law liability to maintain his wife and children and no doubt the word “reasonable” has to be interpreted against the background of the standard of life which he has previously maintained.” Before making any such order, the court will consider the value of the net estate or the estate available, the interests of the other beneficiaries under the estate and any reasons why a testator may have decided in the manner that he did, such as whether the relationship of a dependent with the testator was good and evidence, any evidence is admissible to show this fact [section 20(3) and section 21 of the WA] (See also Vrint and Diamond above). When a court makes an order, it is at its discretion and the order when made may take the form of a lump sum payment, periodic payments or an interest in some immovable asset of a testator for the life of the dependent or some lesser period and when maintenance ordered is periodic, this will terminate not later than [section 20(2) of the WA]: a) In case of spouse, on death or re-marriage; b) In case of a child, on attaining the age of 18 years or leaving school whichever last occurs or the child dies; c) In case of a child under a disability, on the cesser of the disability or death of the child; d) In the case of a parent, on the death of the parent. An application for relief, however, must be made within six months of a grant of representation for general purposes with regard to the testator’s estate [section 22 of the WA]. For this reason, it is prudent for the personal Page 85 of 105 representative not to distribute the estate until after six months have elapsed from the date of the grant or alternatively until after the executor’s year. The court order effectively varies the provisions of the will of the testator BUT does not alter the will and the order can itself be varied to include or exclude dependents depending on evidence produced to the court. There are four points to be considered in order for a dependent to qualify for a Section 20 relief: 1. Must be a dependent within the meaning of that word as defined by the Act, i.e. spouse, child, or parent. 2. Must be unable to support himself or herself from any source whatsoever either because of pure poverty or some disability such as age, infirmity, or insanity. 3. The net estate must be sufficient to support such relief. 4. Application must be made written six months of grant of representation for general purposes. 2. HOW DOES A WILL OPERATE A. The General Rule First of all, a will has to be read as a whole and understood before any effect can be given to it. Section 6(1) of the Wills Act provides that a will must be in writing and the only thing that needs to be ascertained then is the meaning of the words actually used in that writing. Next, the words used in the will must be given their natural and ordinary meaning except when that leads to absurd results or inconsistencies (Re: Bailey (1945) Ch. 191). In that case a testatrix in a will made without professional help, after giving a house to a named beneficiary and several pecuniary legacies to named persons appointed Marjorie James as her “residuary legatee.” At her death the testatrix possessed personal estate worth under 300 Pounds Sterling and several houses apart from the one specifically given Page 86 of 105 which were worth Three thousand five hundred Pounds sterling. The meaning of “legatee” meant one who receives “Personalty” only. It was held that there was sufficient context in the will and the circumstances of the case to show that “residuary legatee” was meant to be “residuary beneficiary” and so Marjorie James took the remainder of the estate including houses. It will not be a question of what the testator meant to do or what he meant to achieve when he made the will but rather what the words used mean in a particular case. While the courts will, and they are required by law to, try as much as possible to give effect to a testator’s intention so as to prevent intestacy, the courts have no power to alter or rewrite a will. Section 16 (1). However, where certain words or expressions have a special meaning or more than one meaning, the special meaning or the appropriate meaning will be applied if that will give effect to a testator’s intention. Section 16(2). When a difficulty arises in construing some part of a will the court will try to see what that would have meant at the time of its execution because although a will speaks from death as regards most aspects of it, the words or expressions used can have a particular or peculiar meaning at the time of execution and quite something else at the testator’s death. As an example, a will executed in Zambia in 1962 leaving property to my “children”, would in the ordinary legal meaning of the word “children” refer to legitimate children only even if a testator died today when after 1989 the Wills Act recognizes illegitimate children unless the Will is republished. Another example is where a testator makes his will domiciled in Zambia and dies domiciled in South Africa, the will should be construed as it would have meant in Zambia at its execution. Where the language used in a will is vague, the courts will try to find some meaning within the general intention of the rest of the will to prevent intestacy, but they will not rewrite the will. However, where the intention of a Page 87 of 105 testator is sufficiently clear from the rest of the will, courts have supplied words or re-arranged words which had clearly been omitted or made by mistake and senseless words have similarly been disregarded, [see Bacharach’s Will Trusts (1959) Ch. 245]. In that case a testator after directing that his business should not be sold without his wife’s consent, devised and bequeathed his residuary estate on trust to pay and apply the income to be divided into four equal shares “one part” to each of my children (he had two) and “two parts” to my wife as shall survive me and attain the age of 23 years and if more than one child in equal shares and if only one such child to pay half of such parts to that child. It was held that the court could re-arrange the wording so that the will should read “four shares two parts to my wife and one part to each of my children” as it was clear from the will that the testator intended the wife to receive half of the residue. B. Extrinsic Evidence (1) Surrounding Circumstances Evidence of facts and circumstances existing when the will was made is always admissible. Evidence will therefore be admissible to show that certain words had a peculiar meaning to a testator either because of the particular place where the testator lived or perhaps a particular class of society where the testator belonged. 2. Words with More Than One Meaning When a description in a will is capable of applying to more than one thing or person, evidence is admissible to explain an ambiguity. When a will appears perfect on the face of it but when an attempt is made to apply a particular part of a will and a difficult arises it is said that the problem or ambiguity is latent i.e. not apparent, and evidence is admissible to explain such problem. If such evidence fails to resolve the ambiguity, the gift will be void for uncertainty. Page 88 of 105 However, if the ambiguity is quite apparent from the will itself, the ambiguity is said to be patent, and evidence may not be admissible. C. Contradiction Evidence to explain a contradiction is not normally admissible. 3. WHEN DOES A WILL START TO SPEAK? (A) As to Property A will speaks from death as regards all property comprised in it unless a contrary intention appears (Section 16(3) of the Wills Act). A will is, therefore, capable of disposing of all property owned by a Testator at his death even if he acquired such property after making the will. This is true of descriptions of a class of objects which are capable of increasing or decreasing. Thus, a gift of “all land which I am possessed of “will include all land owned by the testator at his death including fixtures thereto even if these were affixed after the will was made. The land owned can change at any time: it can increase or decrease. However, a gift of a specific object existing at the date of the will appears to show a contrary intention to take it out of Section 16(3). A gift of “my Red Land Rover to B” and a testator subsequently sells that Land Rover and buys another one, will not pass the new Land Rover under the will unless it is also red in colour. The gift is said to be adeemed because the specific red Land Rover has ceased to exist or to belong to the testator. See in Re Sykes (1927) 1 Ch. 364 where a testatrix in her will gave “my piano” to Beatrice Elizabeth Leigh. She subsequently sold the piano she owned at the date of the will to Y who was married to Ms Leigh and bought a new and more expensive piano which she owned at her death. It was held that the new piano was not the one referred to in the will and did not pass. (B) As it relates to Persons Page 89 of 105 (i) Class Gifts A class gift or a gift to a class is a gift of property to all who come within some description, the property being divisible in shares varying according to the number in the class. For example, a gift of property: (a) To my children who shall attain the age of 21 years. (b) To my children Andrew Mark and Dorothy and such of my children born hereafter as shall attain the age 21 years or marry. (c) To A B C and D if living. (d) To all the ZIALE students as shall be in class on Tuesday 20th January. These are all class gifts. A number of those who can qualify can change anytime, up or down. A gift to “five sons of Banda” or a gift to “my six children” or a gift to the 388 Students of ZIALE is not a class gift. The number of those who can qualify is fixed and cannot change. The difference is that, in the first example, if one member of the group drops out the shares of the others will increase while, in the second example, a specific share is given to those existing at the date of the will or those who make up the group at the date indicated and if one dies before the testator the personal representative will be able to claim it. Class gifts are construed on the principle that a testator’s intention shall govern the persons who are to take under a will. A problem arises when one member of a class or group becomes qualified to receive his share before the maximum number of the members of the class can be fixed. For example, to “all my grandchildren as and when they attain the age of 21 or being female marry under that age.” As soon as the first grandchild attains 21 or being female marries, he or she qualifies to receive his or her share. Page 90 of 105 However, if all the future grandchildren are to be included, it would not be safe to give a share to the first one to qualify. It will be difficult to determine the size of the share until all his parents, aunts, uncles are dead, because it is only then that the maximum number that can qualify will be known and the minimum share ascertained. In order to expedite the distribution of property the courts have established a rule known as the rule in Andrews v. Partington which states that each share is to be paid out at the earliest rather than the latest possible moment, and therefore the class is limited to those in existence when the first capital share becomes payable. This is a rule of convenience rather than a rule for ascertaining the testator’s intention and is subject to a contrary intention in the will (as by directing in a will that a gift is not to vest until the youngest member attains 21 or being female marries under that age). The rule as stated is obviously inconvenient to those who get excluded by it. Some judges were not happy with the rule and as a result of various refinements the rule may now be stated as follows: “A class closes when the first member becomes entitled in possession; but where the shares of its members are to vest at birth, it will remain open indefinitely unless a member was born before the testator’s death or before the end of some intermediate limitation. All persons born after the closing of the class are excluded.” For example: 1) A gift to “all my sisters”. The class will close when the testator dies if any sisters existed at the death of the testator. Any sister born after that will not be included. But if no sister was alive at the testator’s death, there is an exception to the rule and any sister born after the death of the testator will qualify. If only one member of the group was born at the testator’s death, the class closes at that time. 2) A gift to “all my grandchildren who attain 21”. The class will close when the first attains that age irrespective of when such grandchild was born. Page 91 of 105 When it closes all grandchildren alive at that time are included. However, their interests will only vest when they attain the age of 21 years but if they die before that age, they are treated as never having been born and lose out. The survivors will receive increased shares. 3) A gift “to A for life remainder to all his grandchildren who attain 21”. The class will close on A’s death or the life tenants death if by then any grand child who survived the testator or was born after the testator’s death has attained 21. The grandchild does not need to survive A as his interest will have vested on attaining 21 even if it is during the life time of A. But if there were no grandchildren at A’s death or only infant grandchildren, the class will close when the first attains 21. When a will relates to a group or a class, then its speaks from the testator’s death. This rule can also be circumvented by a contrary intention in the will. (ii) Gifts to Individuals In the case of gifts to identified or existing individuals, the date of the Will is normally the relevant time, that is to say, the Will speaks from its date. A gift to the eldest daughter of Mary is a gift to that daughter if one existed at the date of the Will. If she dies before the testator, the gift lapses and the eldest daughter at the testator’s death gets nothing. However, if Mary had no daughter at the date of the Will, then it is the first person who will answer that description who will take the gift (see Re Hickman 1948 All ER 303). In that case: By a codicil to her Will dated July 12, 1914, the testatrix, who died on Sept. 13, 1914, gave a pearl necklace to her daughter in law MWH for her life and after her death “to the wife of my grandson AEH absolutely ……” The grandson was not married at the date of the codicil or at the date of the death of the testatrix. The grandson’s first marriage, which took place in 1919, was dissolved and in 1940 he married again. MWH, the daughter in law died in 1946 and AEH, the grandson died in March 1947. The question was whether the former wife of the grandson or his widow was entitled to the necklace: Page 92 of 105 It was held that the first person to answer the description of being the wife of the grandson was the person entitled. The former wife took to the detriment of the widow. 4. DEVISES AND BEQUESTS A gift of real property in a will is technically called a “devise” while a gift of personalty or movable property in a will is called a “bequest” or a “legacy”. It is, however, not necessary to use the words “devise” or “bequeath” in order to pass real or personal property in a will and any words indicating an intention to give the interest specified will suffice. According to English Legal terminology “real property” as we know relates to freehold land and “personal property” relates to any other property including leaseholds. We will therefore generally call our gifts bequests or legacies or simply gifts. Classification of Legacies These may be classified under three heads namely general, specific, and demonstrative. This classification is very important for the purposes of administering an estate because the order of distribution of the assets will depend or be based on such classifications. a) General Legacy A legacy is general where it does not amount to a gift of any particular thing as distinguished from all others of the same kind such as “a Diamond ring” the sum of K100, 000.00” a “horse” not referring to any particular diamond ring, particular sum of money or a particular horse. These are all general legacies. These are also sometimes known as “Pecuniary Legacies” although the latter term is normally associated with gifts of money. b) Specific Legacy For a legacy to be specific, the thing given must be an identified part of a testator’s existing property, separated or distinguished from the rest of his estate. A legacy of “house No. 2 Cairo Road Lusaka” my horse which won Page 93 of 105 (a particular) race” or “my K1m deposited at ZANACO main branch” are specific. But, a gift of K1m from my account at ZANACO is not specific. A Debt forgiven is a specific legacy of the sum owed. c) Demonstrative Legacy A legacy is demonstrative if it is general in nature but a particular source of satisfying it is pointed out or provided such as the example of “a gift of K1m from my account at ZANACO” above. The gift is of K1m but if it is not easy to find K1m let it come out of the account at ZANACO. If a person left a gift of a Toyota Corolla from among his cars at his Farm, this would be a gift of any Toyota Corolla but if one cannot be found easily, it can be got from his farm. 5. FAILURE OF LEGACIES I. LAPSE a) General Rule The General rule, as already seen, is that a Will takes effect from death and a gift lapses if the beneficiary dies before the testator (Section 16 (10)). In such a case unless a contrary intention appears in a Will, the gift will fail and fall into residue [section 6(8) and section 18)] but if there is no residue or the gift itself was the residue, there will be a partial intestacy as to that property affected by such a gift [section 4(2) ISA]. b) General Rule Excluded There are situations where the general rule will not apply: i. A gift intended to satisfy a moral obligation recognized by a testator, such as the settlement of a debt even if statute barred or affected by bankruptcy laws may not lapse. ii. A gift to a beneficiary who dies before the testator leaving issue surviving him does not lapse (see section 16(11) of the Wills Act). The gift devolves on the issue. Note the issue must survive both the beneficiary and the testator to save the gift. Page 94 of 105 Section 16(11) should not apply to a class gift such as a gift to “all my children” even if there is only one member of that class. The reason is that membership of a class is normally ascertained at a testator’s death and those dying before the testator simply fail to become members of that class. However, a gift “to four daughters of Mulenga in equal shares” is not a class gift as it gives something to each of those daughters alive at the date of the will. The section will not save a gift that lapses, anyway, on the donee’s death, such as when it is to be held on a joint tenancy as “to my children A and B as joint tenants” and A predeceases the testator, or a contingent gift as to X as and when he attains the age of 25 and X dies at the age 23. II. COMMORIENTES Where two people die in circumstances where it is difficult to determine which of them died first, you have a commorientes. The word simply means dying together. When two people die in circumstances where it is difficult to determine which of them died first, Section 16(12) of the Wills Act says the beneficiary is presumed to survive the testator. Confusion, however, arises when the two people had executed mutual wills, because “the beneficiary survives the testator or the testator predeceases the beneficiary.” Heads you lose tails I win. Which beneficiary? The section makes an attempt at an answer, but it is not satisfactory. However, as we shall see later, the Intestate Succession Act is a little more reasonable as it presumes the younger person always outliving the older – just as nature used to do in Zambia in the old days! English law follows our intestate law (never mind which was first) except for husband and wife where English law prefers both to die at the same time so that no one claims to be the winner and thereby grabbing all the property. Page 95 of 105 The doctrine applies not only when people die in the same accident, but it will also apply even where one dies in a road accident on the Kabwe Road and the other one dies of natural causes while watching the World Cup in Russia, if the deaths are apparently on the same day. It is, therefore, always prudent, for this reason to include a survivorship clause in a will. Such as: “If my wife shall survive me for a period of thirty days then but not otherwise I give to my said wife ……/or on trust for my said wife...” III. ADEMPTION We have seen that a gift of a specific asset, fails when a testator disposes of such asset in his life time. The gift fails because nothing, but the specific asset was given to the beneficiary. The gift will fail even if the testator buys a similar asset which he owns at his death as where a testator gives “my house No. 2 Roan Road” and at death he is found to no longer own No. 2 Roan Road and instead acquired No. 4 Roan Road. The specific asset referred to in the Will, No. 2 Roan Road, is said to be addeemed when it is thus disposed of in the testator’s life time even if at his death he is found to own No. 4 Roan Road. The asset is addeemed if it is changed into something different even if the thing into which it is changed is in the testator’s possession at his death and it is immaterial whether the change is effected by the testator himself or by some external authority because ademption is not dependent on the intention of a testator. See Harrison v Jackson (1877) 7 Ch.D.339. In that case a testator bequeathed “1000 Pounds Sterling D Stock in the London and North Western Railway Company now standing in the names of the trustees of my settlement and bequeathed to me by my wife (and which stock it is my intention to have transferred into my name) unto AB & C upon trust for A”. The stock was never Page 96 of 105 transferred into his name but was paid off by the company and re-invested elsewhere by his desire. It was held that the legacy was addeemed and the new asset as converted became part of the residue and the residuary legatees became entitled to the new investments. A legacy may be addeemed pro tanto as where the testator disposes of part of the specific bequest, such as a gift of a specific house and the testator mortgages the house. If the house is available at the testator’s death, the gift is a gift of the house less the value of the mortgage. The gift of house No. 2 Roan Road with all its contents and at testator’s death No. 2 Roan Road is found to still belong to the testator but empty. The contents are said to have been addeemed. There is no ademption where the subject matter is only changed in name or form but remains substantially the same as where a person owns shares in Zambia Railways Ltd and the company is re-constructed upon privatization into the North and South Railway Company Ltd and the old shareholders are given shares in the new company of an equal value. A general legacy is not within this principle of ademption. A personal representative must find the general legacy from other assets of the testator if these are still available. A demonstrative legacy is also not subject to ademption because even when the specific source of the gift is no longer in existence, the personal representative must pay it from some other assets of the testator. IV. ABATEMENT A legacy is said to abate when its value or quantity reduces such as where a testator gives a legacy of the residue of my estate to each of A, B and C in equal shares, then, in an ideal situation where the estate is solvent the Personal Representative will, as we have already seen, begin his work by Page 97 of 105 collecting all the assets of the deceased and know all the liabilities or debts of the deceased. He then sets aside: (a) The Specific Legacies. (b) Sufficient funds to meet Demonstrative Legacies even when the fund specifically designated for the purpose does not exist. (c) Sufficient funds to meet Pecuniary Legacies or General Legacies. The Assets left are then applied to meet all the liabilities of the estate. If after paying all the debts of the estate there are still sufficient assets left without touching or resorting to (a), (b), (c) above, there will be an Accretion to the General Legacies. However, if the funds or assets which the PR starts off in paying the liabilities are insufficient then he will resort to the assets in (c) above first. This will cause the General Legacies to abate or reduce in value or even in quantity. If the assets in (c) are also insufficient then the assets in (b) And (a) above together will be resorted to. The General Legacies therefore abate first while the Specific Legacies abate last after the General Legacies. Demonstrative Legacies will not abate even when there is a deficiency of assets as long as the fund out of which is payable is not exhausted or as long as there are sufficient assets out of which it can be funded. Demonstrative Legacies therefore enjoy the best of both worlds, no ademption and no abatement until at the end. PART III INTESTATE SUCCESSION We must now consider what happens when a person dies intestate. Since the person would have died without leaving instructions, as to how his property and problems are to be handled after his death, we shall look to the law and Page 98 of 105 rules relating to intestacy for guidance. If a person dies wholly intestate, it is this law and rules which will determine the devolution of all his property but if he dies partly testate and partly intestate, the intestacy law and rules will govern all his property which will not be covered by his Will, (see Section 4 of the Intestate Succession Act). Persons dying intestate and domiciled in Zambia were, prior to 1989, subject to either English intestate succession law or to Zambian customary law for those to whom such customary law applied. See Hwalima v Hwalima 1968 ZLR 164. In that case, Hwalima died leaving a Will executed in accordance with the Wills Act 1837. On a question whether an African was capable of disposing of his property by means of a Will and whether the terms of such a Will can have effect despite being contrary to customary law. It was held an African may accept an authority other than his customary authority just as at common law a person is entitled to subject himself to any law of his choosing. There was no written law, and as far as could be ascertained, and no customary law to the contrary. English intestate succession law still applies to Zambia for all those dying intestate and domiciled in Zambia if customary law does not apply to them, (see Section 2(1) of the Intestate Succession Act 1989 and section 11 of the High Court Act). For our purposes we shall look at the devolution of intestacy law over three distinct periods namely, Pre-1926, Post 1925 and Post 1989. SUCCESSION AFTER 1989 A) English Law English intestate law still applies to Zambia for all those dying intestate domiciled in Zambia and to whom Zambian customary law does not apply, (see Section 2(1) of the Act). The position is therefore the same as in 2. above, post 1925 law. B) Customary Law Page 99 of 105 There is no change from the Post 1925 period but in 1989 the Interstate Succession Act was introduced to try to provide some uniform method of succession on an intestacy throughout the Country and since then reliance is now being placed more on the Act. Customary law is still enforceable by the Courts. C) The Intestate Succession Act 1989 The Act has not repealed or amended any law then existing not even customary law and has not cured all the intended problems and, in some cases, it has created its own. In principle the Act follows English intestate law but those beneficially entitled, under the Act, are, in the order of priority as follows: a. “Priority Dependents” defined as spouse, child, and parent. Priority inter se follows this same order. These are the only ones who can apply to court for the equivalent of Section 20 relief under the Wills Acts, (Proviso to Section 5 of the ISA). b. “Dependents” (the “ordinary dependent”) defined to mean a person maintained by the intestate and who was: i) Living with the intestate; or ii) A minor whose education was being provided by the intestate and who is incapable of supporting himself. See the case of Oparacha v Murambiwa. c. “Near Relatives” defined to mean issue, brother, sister, grandparent, and other remoter descendants of the intestate. NB: This contrasts with the Act’s own definition of “issue”. d. The State. Only comes in where no relative or good friend of the intestate can be traced in the world. The estate will be claimed as bona vacancia through the Administrator General. The estate will find a charity and donate the estate to such charity. We will now look at the above in a little more detail and consider who among those listed is beneficially entitled to what in the estate of the intestate. Page 100 of 105 However, in order to arrive at the distributable estate, the Administrator will need to first identify: i) In a monogamous marriage, the “personal chattels” of the intestate [section 8 of ISA] ii) In a polygamous marriage: a. The “homestead property” of the intestate, which is defined as “personal chattels” of an intestate used by him and his family of a particular household [section10(a) of ISA]. b. The “common property” of an intestate defined as all the “personal chattels” of the intestate used in common by the intestate his wives and children not being “homestead property”. If the estate is insolvent the Administrator proceeds to pay the debts and liabilities using whatever available assets including the personal chattels. However, if the estate is solvent without the need to resort to personal chattels at all, irrespective of the type of marriage he must then: i) set aside the “personal chattels” and in a polygamous marriage these would be the “homestead property” and “common property.” [Section 8 & 10 ISA]. ii) Pay all the debts and liabilities of the estate including the funeral and Administration expenses [Sect. 19(1)(b)]. iii) set aside a fund to meet pecuniary legacies (where there is a will). After all the above have been attended to, any asset or assets remaining will make the residuary estate or the residue of the estate and in principle this is what is available for distribution to those beneficially entitled. However, if the residuary estate includes a house the Administrator must set aside such a house [section 9(1) ISA]. If the residuary estate includes more than one house, the Administrator must, in addition, set aside a house selected by a spouse or spouses and the children of the intestate. [Sect. 9 (2) ISA]. Please note that the house does not need to be or have been the matrimonial home. If the marriage was polygamous, the spouses and the children of the intestate will hold the house as tenants in common (a problem), but the interest of the spouse(s) is only for as long as the spouse(s) remain alive or unmarried Page 101 of 105 [section 9(1)(b) ISA]. This means that a house really belongs to the children of the intestate but that the surviving spouse(s) can use it in any way while alive or unmarried. After all this has been done or attended to, the Administrator must ascertain which “priority relation” or next of kin and “ordinary” dependent have survived the intestate as distribution is dependent on those survivors [secs 5, 6 & 7 ISA]. The rights of the survivors are rather unsatisfactory as in most cases heavy responsibility is placed on the administrator to make difficult decisions. We will look, as an example, on the rights of a surviving spouse and then the children. 1) Rights of Surviving Spouse a. Where a spouse survives with: i. No child, parent or dependent of the intestate, that is to say the spouse is the only survivor out of all those who can claim. In this scenario, the spouse will get: a) Personal chattels used by the intestate with that family absolutely [Sect. 8 & 10 ISA]. b) A life interest which can also terminate on re-marriage [Sect. 9(1) ISA]. Where there is more than one house, such house must be selected by the spouse [section 9(2)] c) 60% of the residue absolutely and where there is more than one surviving spouse in unequal shares [Sect. 5(1)(a) & 7(f)]. ii. A spouse survives and there is a child and an “ordinary” dependent of the intestate but no parents of the intestate. Under this scenario, the spouse will get: a) Personal chattels used by the intestate with that spouse equally with the child or children of the intestate (Sect. 8). b) An equal share of “common property” with the other families in a polygamous marriage but as these are Page 102 of 105 “personal chattels” equally with the child or children of the intestate (Sect 8 &10). c) A life interest which is also terminable on remarriage, in common with a child(ren) of the intestate, in a house (and where applicable) selected by the spouse or the children of the intestate (Sect 9). This is also in accordance with Section 4(b) of the Trust Restriction Act 1970. d) 25% of the residue absolutely but if more than one spouse in unequal shares [Sect. 5(1)(a) read with Sect. 7(a)] ISA. iii. Where the spouse survives and there is a parent and an “ordinary” dependent but no child, the spouse will get: a) Personal chattels used by the intestate with that spouse absolutely [section 8 ISA]. b) An equal share of the common property with the other families in a polygamous marriage (personal chattels) [section 10(b)]. c) A life interest in a house selected by her (and where applicable) selected by a spouse but which can also terminate on remarriage. The house continues being part of the residue when the spouse’s interest terminates. d) 40% of the residue but if there is more than one spouse in unequal shares [Sect. 5(a) read with Sect 7 (b)]. iv. The spouse survives a child, and a parent but no “ordinary” dependent of the intestate, the spouse will get: a) Personal chattels used by the intestate with that spouse equally and absolutely with the child [section 8]. b) An equal share of common property with other families in a polygamous marriage equally with a child or children of the intestate [section 10(b)]. c) A life interest, which can also terminate on remarriage in common with a child or children of the intestate in a Page 103 of 105 house selected by the spouse and child(ren) [section 9(1)(2)]. d) 20% of the residue and if more than one in unequal shares [Sect. 5(a) & sec 7(c)]. v. A child, parent and dependent, the spouse will get: a) Personal chattels absolutely and equally with child [Sect. 8] b) Life interest in a house selected by the spouse and child in common with the child but interest terminable on remarriage (Sect. 9). c) 20% of the residue absolutely and if more than one unequally (Sect. 5 (a)). 2. Rights of a Surviving Child a. Where a child survives with: I. No spouse of the intestate, no parent, and no dependent the child will get: a) Personal chattels absolutely and in an unequal shares (Sect. 8). b) Absolute interest in a house (and where applicable) selected by him if there is more than one child surviving in unequal shares [section 9]. c) 100% of the residue absolutely and if more than one surviving child in unequal shares. II. A child survives with a spouse of the intestate, no parents of the intestate, and no dependents of the intestate, the child will get: a) Personal chattels absolutely equally with the spouse [sections 8 & 10(a)] b) An absolute interest in an undivided share in a house shared with the spouse who takes a life interest [section 9] c) 65% of the residue if more than one child in unequal shares [section 5(b) & sec 7(a)] d) A reversion in the spouse’s interest in a house when spouse’s life interest terminates either because he or she has died or decided to get married [Sect. 9] Page 104 of 105 III. The child survives with a spouse and parent but no dependents of the intestate, the child will get: a) Personal chattels equally with the spouse and if more than one, the child’s share is divided into unequal portions. b) An absolute interest in a house (where applicable) selected by the child and a spouse in common with that spouse and if more than one child, in unequal shares. *****THE END***** Page 105 of 105