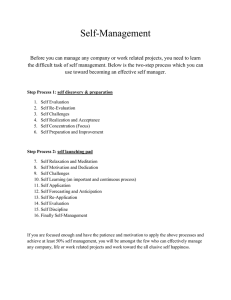

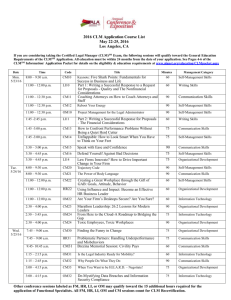

Patient Self-Management Patrick McGowan, PhD University of Victoria Centre on Aging Workshop Overview Chronic conditions Complexity of behaviour Chronic vs. acute conditions Patient needs Role of self-management BC Expanded Chronic Care Model Practice The “Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions” program Program effectiveness Other BC Programs to encourage patient selfmanagement What’s the objective? Judy’s Story Why does Judy eat this way? Chicken Strips, fries, Caesar Salad and peach pie PRECEDE-PROCEED model of health promotion planning Green & Kreuter, 1999 Predisposing factors Reinforcing factors Enabling factors Behaviour and Lifestyle Environment Health Quality of Life Predisposing Factors Knowledge Beliefs Attitudes Values Motivation Confidence Self-efficacy Reinforcing Factors Family Peers Employers Comforting Relieves stress Enabling Factors Health-related skills Accessibility to information Accessibility of health resources Differences Between Acute and Chronic Disease ACUTE DISEASE CHRONIC DISEASE BEGINNING Rapid Gradual CAUSE Usually one Many DURATION Short Indefinite DIAGNOSIS Commonly accurate Often uncertain, especially early DIAGNOSTIC TESTS Often decisive Often of limited value TREATMENT Cure common Cure rare ROLE OF PROFESSIONAL Select and conduct therapy Teacher and partner ROLE OF PATIENT Follow orders Partner of health professionals, responsible for daily management New Tasks 1. Recognizing and acting on their symptoms 2. Making most effective use of their medications and treatments 3. Dealing with acute attacks or exacerbations (managing emergencies) 4. Maintaining their nutrition and diet 5. Maintaining adequate exercise 6. Giving up smoking 7. Using stress reduction techniques 8. Interacting effectively with their health providers 9. Using community resources 10. Managing work and the resources of employment services (adapting to work) 11. Managing relations with significant others 12. Managing their psychological responses to illness. Traditional Patient Education Asthma Diabetes Insulin injection Blood-glucose monitoring Healthy eating (glucose levels) Heart disease Proper use of inhaler Self-monitoring Environmental control measures Medication Information on pacemakers, arrhythmias, chest pain, acute complications healthy eating (cholesterol) Rheumatoid arthritis Medication Joint protection & use of adaptive equipment Patient Contact with Health Professionals Time managing at home over 1 year GP visits per annum = 1 hour Visits to specialists = 1 hour PT, OT, Dietitian = 10 hours Total = 12 hours with professionals 364.5 days managing on their own or 8748 hours Barlow, J. Interdisciplinary Research Centre in Health, School of Health & Social Sciences, Coventry University, May 2003. Definition of Self-Management The tasks that individuals must undertake to live well with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions. Report of a Summit. The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit. September 2004 Self-management support is defined as the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions by health care staff to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support. FIG. 1: THE EXPANDED CHRONIC CARE MODEL: INTEGRATING POPULATION HEALTH PROMOTION Build Healthy Public Policy Create Supportive Enviro nment s Strengthen Community Action Activated Community Self Management / Develop Personal Skills Informed Activated Patient Delivery System Design / Reorient Health Servic es Productive Interactions & Relationships Information Systems Decision Support Prepared Proactive Practice Team Population Health Outcomes / Functional and Clinical Outcomes Prepared Proactive Community Partners Traditional Definition of Self-Management “Self-management behaviours” for diabetes defined as: - self injection of insulin - self-monitoring of glucose levels - eating properly - smoking cessation - exercising - taking medications properly Practicing these “self-management behaviours” there is an expectation that intermediate goals will be achieved: - metabolic control - optimal blood glucose levels - blood lipid control - optimal weight And, if these intermediate goals are achieved, there should be better diabetes outcomes: - a reduction in morbidity (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy) - fewer hospitalizations - a reduction in diabetes-related health care costs - reduced mortality Traditional Patient Education Self-Management Education Information & What is taught? technical skills about the disease Skills on how to act on problems Problems reflect inadequate control of the disease The patient identifies problems experienced that may or may not be related to the disease Education is diseasespecific and teaches information and technical skills related to the disease Education provides problem-solving skills relevant to the consequences of chronic conditions in general How are problems formulated? What is the relation of education to the disease? What is the theory underlying the education? What is the goal? Who is the educator? Traditional Patient Education Self-Management Education Disease-specific knowledge creates behaviour change, which in turn produces better clinical outcomes Greater patient confidence in capacity to make life-improving changes (self-efficacy) yields better clinical outcomes Compliance with behaviour changes taught to the patient to improve clinical outcomes Increased self-efficacy to improve clinical outcomes A health professional A health professional, peer leader, or other patients, often in group settings Facilitating Patient Self-Management 1. 2. 3. Using “Mastery Learning” strategies with patients. Teaching and practicing “Problem-Solving” with patients. Encouraging patients to participate in the community patient self-management program. 1. Mastery Learning Goal → Action Plan → Follow-Up Judy’s Goal A Goal is something that you should be able to accomplish in 3 to 6 months from now. It’s too big to be able to accomplish all at once. Judy replies: “I want to loose some weight” An Action Plan is something that you can do between this visit and the next that contributes to achieving that goal. Parts of an Action Plan 1. Something YOU want to do 2. Reasonable 3. Behaviour-specific 4. Answer the questions: What How much When How often 5. Confidence level that you will complete the ENTIRE action plan Goal – Judy wants to lose some weight This week I am not going to eat anything after 7 PM on at least 5 of the 7 days. I am 8 confident that I will accomplish this. The Action Plan must reflect contributions, preferences, and assessments of feasibility by the patient, not mere acquiescence to physician recommendations. 2. Problem-Solving Steps Identity the problem List ideas Select one Assess the results Substitute another idea Utilize other resources Accept that the problem may not be solvable now Problem Solving Judy identifies her problem: “I am not doing any exercise” Possible reasons: ¾ I don’t have the right clothes ¾ I don’t know what type of exercise I am supposed to do ¾ I have no one to exercise with ¾ Exercise is boring ¾ It’s painful to exercise ¾ I doesn’t have the time ¾ I am self-conscious about her body shape ¾ I can’t get motivated to exercise It must be Judy who identifies the main reason why she isn’t exercising 1. Identify the problem – I am not exercising because I just can’t seem to get motivated. 2. 3. List ideas • I can join a club (pay the fee) • I can make a exercise schedule and reward herself • I can get a friend to go with me on scheduled walks • I can persuade hubby to go for walks with me 3 times a week • I can exercise at work (e.g., use the stairs, walk at lunch time) • I can make an action plan and let all her friends and work colleagues know about it Select one idea to try – I will get my husband to go for a 45 minute walk with me 3 times this week. 4. Assess the results 4. Substitute another idea 5. Utilize other resources 6. Accept that the problem may not be solvable now Health Care Provider Patient Self-Management Education Individuals and health care providers collaborate in problem solving, addressing issues and concerns to both parties. Self-Management should be linked to the individual’s regular source of medical care. Communication among the patient, the selfmanagement delivery staff, and the patient’s usual provider is likely to improve results. Practice: Problem-Solving with a Colleague 1. Identify the problem (relating to either eating or exercise) 2. List ideas that may solve the problem 3. Select one idea to try “What prevents you from exercising the way you think you should and want to?” “What prevents you from eating the way you think you should or want to?” Action Plan for this Week Something YOU want to do Reasonable Behaviour-specific Answer the questions: What How much When How often Confidence level that you will complete the ENTIRE action plan The Chronic Disease SelfManagement Program “Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Health Conditions” Overview of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program Persons with any type of chronic health conditions Self-referral Spouses and significant others may participate Led by pairs of lay persons with chronic health conditions Leaders receive a 4-day training workshop Overview of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program Leaders follow a scripted Leader’s Manual Course is given once a week for 2 ½ hours for 6 weeks Ideal class size is 10 to 12 persons Participants receive “Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions” workbook No cost to participants History of self-management in Canada What do people learn in selfmanagement programs? Information From the program From other participants Practical Skills Getting started skills (e.g., exercise) Problem-solving skills Communication skills Working with health care professionals Dealing with anger/fear/frustration Practical Skills (cont’d) Dealing with depression Dealing with fatigue Dealing with shortness of breath Evaluating treatment options Cognitive Techniques Self-talk Relaxation techniques Self-efficacy Enhancing Strategies Self-efficacy: Health outcomes Modeling Mastery learning Vicarious learning Persuasion Program Implementation Receptiveness Dissemination Integration OVERALL TOTALS 2000 to 2004 Leader Training Workshops Leaders Trained Courses Delivered Participants Northern 9 84 20 184 Interior 19 223 98 1066 Fraser 6 59 31 381 Vancouver Coastal 28 315 210 2150 Vancouver Island 15 154 48 447 TOTAL 77 835 407 4228 Region Chronic Disease SelfManagement Program Program Effectiveness http://bcauditor.com Unusual Features of Audit Recommendations Often, BC audits examine the processes used to implement a particular policy decision within a particular ministry or agency. In such a situation, what to address in recommendations, and who to address them to, is relatively straightforward. But… In essence, what we have found is not a program requiring relatively modest changes, but the absence of an organized program. Our recommendations, therefore, have to start from first principles: Principles of Primary Prevention Intervention choices must be evidencebased. Effective interventions are likely to be those that provide the right treatment in sufficient dosage for sufficient time, and are targeted at multiple points of intervention. Principles for Secondary Prevention Effective interventions would likely use treatment plans similar to those in recent successful trials such as the Diabetes Prevention Program. Principles in Tertiary Care Effectiveness would likely result from care delivery organized using an integrated approach to management, as exemplified by the Chronic Care Model. Effectiveness of CDSMP Treatment subjects when compared with control subjects, demonstrated improvements at 6 months in weekly minutes of exercise, frequency of cognitive symptom management, communication with physicians, selfreported health, health distress, fatigue, disability, and social/role activities limitations. They also had fewer hospitalizations and days in hospital. No differences were found in pain/physical discomfort, shortness of breath, or psychological well being. Lorig, K., Sobel, D., Stewart, A., Brown, B., Bandura, A., Ritter, P., Gonzalez, V., Laurent, D. & Holman, H. (1999). Evidence suggesting that a Chronic Disease Self-Management Program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization. Medical Care, 37(1), 5 – 14. 2-Year Follow-up Compared with baseline for each of the 2 years, Emergency Room and outpatient visits and health distress were reduced (P<0.05). Self-efficacy improved (P<0.05). There were no other significant changes. Lorig, K., Ritter, P., Stewart, A., Sobel, D., Brown, B., Bandura, A., Gonzalez, V., Laurent, D. & Holman, H. (2001). Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: Two year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Medical Care, 39(11), 1217 – 1223. Yukon Results At six-months post-program, participants: • were practicing more ways of coping with their symptoms; • had higher levels of self-efficacy to manage their symptoms and to manage their disease; • were less bothered by their illness; • were less depressed; • had more energy; • were less distressed about their health condition; • were experiencing less fatigue and shortness of breath; • were experiencing less pain; • were less limited in their daily activities; and • had better communication with their doctor. Vancouver/Richmond 2001 At six-months post-program, participants: • were practicing more ways of coping with their symptoms; • had a higher level of self-efficacy to manage their symptoms; • had a higher level of self-efficacy to control/manage depression; • had a higher level of self-efficacy to manage their disease; • believed they had better health; • were less limited in their daily activities; • were less bothered by their illness; • were less distressed about their health condition; • were experiencing less shortness of breath; and • were experiencing less pain. Vancouver/Richmond 2003 At six-months post-program, participants: • had a higher level of self-efficacy to manage their symptoms; • believed they had better health; • were less limited in their daily activities; • were less depressed; • had more energy; • were less distressed with their health condition; • were experiencing less shortness of breath; and • had spent less nights in hospital than they had in the previous six-month period. CDSMP Addresses the Determinants of Health • • • • • • • Social Support Networks Education Social Environments Personal Health Practices and Coping Skills Health Services Culture Gender Diabetes Self-Management Leader Training Workshops Location Vancouver Williams Lake Tofino Nanaimo Victoria Alkali Lake Prince George Parksville Sechelt Prince George Campbell River Squamish Vernon Leaders 12 10 11 5, 9 19, 7 5 10 13 13 10, 8 6 11 13 Kelowna Surrey Penticton Castlegar Fort Nelson Kamloops Chemainus Powell River Total: 23 Workshops in 20 Communities 226 trained leaders 17 8 8 7 2 14 11 7 Program Delivery - Participants Location Participants Vancouver 66 Coquitlam 16 Richmond 18 Victoria 83 Ladysmith 6 Nanaimo 27 Sechelt 20 Valemount 18 Campbell River 29 Parksville 10 Qualicum Beach 10 Ladner 16 Vernon 48 Chase 17 Powell River 7 Texada Island Prince George Cowichan Sorrento Falkland Kelowna Surrey Pemberton Penticton Castlegar Hixon Kamloops Chemainus Total: 66 courses in 26 Communities 746 participants 7 65 5 13 22 12 53 9 40 15 15 86 13 Diabetes Self-Management had improved communication with their doctor had a higher level of self-efficacy to manage disease symptoms believed they had better health were less distressed by their symptoms were experiencing less pain had increased the number days they ate breakfast were eating yogurt more often at breakfast had fewer days where they missed taking medications as prescribed Pre- and six-month post program Hemoglobin A1c levels of course participants Cases N Pre Post P-value All 141 .06995 .06887 .161 Pre HgA1c ≤ .06 34 .05600 .05888 .003 Pre HgA1c >.06 ≤ .07 51 .06490 .06445 .640 Pre HgA1c >.07 56 .08032 .07896 .011 BC Projects to encourage Patient Self-Management BC NurseLine – Self-Management Module College of Family Physicians Key Points Knowing isn’t enough – it’s the behaviour! Judy must live her life Focus on the “ends” Programs must be “Best Practice” The integration of separate interventions Contact Information saaa Toll-free line: 1-866-902-3767 Web site: www.coag.uvic.ca/cdsmp www.newperspectivesconf.com