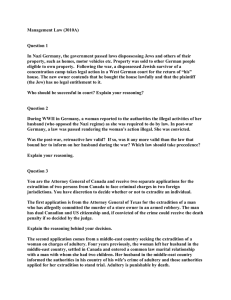

Due Process the Sixth Amendment and International Extradition

advertisement