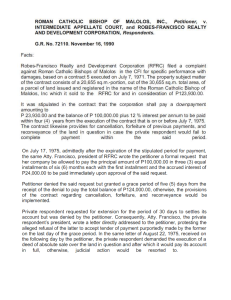

Roman Catholic Bishop vs Robes-Francisco Realty Case

advertisement

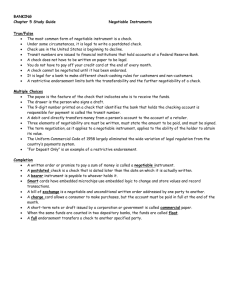

Caltex Philippines v. Court of Appeals How Negotiability is Determined? Caltex (Philippines) vs CA 212 SCRA 448 August 10, 1992 Facts: On various dates, defendant, a commercial banking institution, through its Sucat Branch issued 280 certificates of time deposit (CTDs) in favor of one Angel dela Cruz who is tasked to deposit aggregate amounts. One time Mr. dela Cruz delivered the CTDs to Caltex Philippines in connection with his purchased of fuel products from the latter. However, Sometime in March 1982, he informed Mr. Timoteo Tiangco, the Sucat Branch Manger, that he lost all the certificates of time deposit in dispute. Mr. Tiangco advised said depositor to execute and submit a notarized Affidavit of Loss, as required by defendant bank's procedure, if he desired replacement of said lost CTDs. Angel dela Cruz negotiated and obtained a loan from defendant bank and executed a notarized Deed of Assignment of Time Deposit, which stated, among others, that he surrenders to defendant bank "full control of the indicated time deposits from and after date" of the assignment and further authorizes said bank to pre-terminate, set-off and "apply the said time deposits to the payment of whatever amount or amounts may be due" on the loan upon its maturity. In 1982, Mr. Aranas, Credit Manager of plaintiff Caltex (Phils.) Inc., went to the defendant bank's Sucat branch and presented for verification the CTDs declared lost by Angel dela Cruz alleging that the same were delivered to herein plaintiff "as security for purchases made with Caltex Philippines, Inc." by said depositor. Mr dela Cruz received a letter from the plaintiff formally informing of its possession of the CTDs in question and of its decision to pre-terminate the same. ccordingly, defendant bank rejected the plaintiff's demand and claim for payment of the value of the CTDs in a letter dated February 7, 1983. The loan of Angel dela Cruz with the defendant bank matured and fell due and on August 5, 1983, the latter set-off and applied the time deposits in question to the payment of the matured loan. However, the plaintiff filed the instant complaint, praying that defendant bank be ordered to pay it the aggregate value of the certificates of time deposit of P1,120,000.00 plus accrued interest and compounded interest therein at 16% per annum, moral and exemplary damages as well as attorney's fees. On appeal, CA affirmed the lower court's dismissal of the complaint, and ruled (1) that the subject certificates of deposit are non-negotiable despite being clearly negotiable instruments; (2) that petitioner did not become a holder in due course of the said certificates of deposit; and (3) in disregarding the pertinent provisions of the Code of Commerce relating to lost instruments payable to bearer. Issues: a) Whether certificates of time deposit (CTDs) are negotiable instruments? b) Is the depositor also the bearer of the document? c) Whether petitioner can rightfully recover on the CTDs? Held: The CTDs in question are not negotiable instruments. Section 1 Act No. 2031, otherwise known as the Negotiable Instruments Law, enumerates the requisites for an instrument to become negotiable, viz: (a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer; (b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money; (c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time; (d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and (e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated therein with reasonable certainty. The accepted rule is that the negotiability or non-negotiability of an instrument is determined from the writing, that is, from the face of the instrument itself. In the construction of a bill or note, the intention of the parties is to control, if it can be legally ascertained. While the writing may be read in the light of surrounding circumstances in order to more perfectly understand the intent and meaning of the parties, yet as they have constituted the writing to be the only outward and visible expression of their meaning, no other words are to be added to it or substituted in its stead. The duty of the court in such case is to ascertain, not what the parties may have secretly intended as contradistinguished from what their words express, but what is the meaning of the words they have used. What the parties meant must be determined by what they said. Petitioner's insistence that the CTDs were negotiated to it begs the question. Under the Negotiable Instruments Law, an instrument is negotiated when it is transferred from one person to another in such a manner as to constitute the transferee the holder thereof, and a holder may be the payee or indorsee of a bill or note, who is in possession of it, or the bearer thereof. In the present case, however, there was no negotiation in the sense of a transfer of the legal title to the CTDs in favor of petitioner in which situation, for obvious reasons, mere delivery of the bearer CTDs would have sufficed. Here, the delivery thereof only as security for the purchases of Angel de la Cruz (and we even disregard the fact that the amount involved was not disclosed) could at the most constitute petitioner only as a holder for value by reason of his lien. Accordingly, a negotiation for such purpose cannot be effected by mere delivery of the instrument since, necessarily, the terms thereof and the subsequent disposition of such security, in the event of non-payment of the principal obligation, must be contractually provided for. BALDOMERO INCIONG JR., vs COURT OF APPEALS G.R. No. 96405, June 26, 1996 ROMERO, J.: FACTS: On February 3, 1983, petitioner Baldomero Inciong Jr., co-signed a promisory note worth P50,000 together with Rene Naybe and Gregorio Pantonasas, holding themselves jointly and severallly liable to creditor, Philippine Bank of Communications (PBC). The due date expired without the promissors having paid their obligation even after demands were sent, hence, a complaint for collection of the sum of P50,000 was filed against the obligors. The complaint was dismissed for failure of the plaintiff to prosecute the case, but the lower court reconsidered and the summonses were eventually served. As prayed for by PBCOM, the lower court dismissed the case against defendant Pantanosas. With co-defendant Naybe in Saudi Arabia, only the summons to comaker Inciong was duly served. ISSUE: Whether a creditor can file a claim for the entire obligation against a comaker of a loan? RULING: Yes, a creditor can file for the entire obligation against a co-maker. The promissory note involved in this case expressly states that the three signatories therein are jointly and severally liable, any one, some or all of them may be proceeded against for the entire obligation. The choice is left to the solidary creditor to determine against whom he will enforce collection. Consequently, the dismissal of the case against co-defendant Pantanosas may not be deemed as having discharged petitioner from liability. As regards co-defendant Naybe, suffice it to say that the court never acquired jurisdiction over him. Therefore, PBCOM (P) only have recourse against his co-makers, as provided by law. Inciong signed the promissory note as a solidary co-maker and not as a guarantor. A solidary or joint and several obligation is one in which each debtor is liable for the entire obligation, and each creditor is entitled to demand the whole obligation. —Tolentino, Civil Code of the Philippines, Vol. IV, 1991, p. 217. On the other hand, Article 2047 of the Civil Code states: By guaranty a person, called the guarantor, binds himself to the creditor to fulfill the obligation of the principal debtor in case the latter should fail to do so. If a person binds himself solidarily with the principal debtor, the provisions of Section 4, Chapter 3, Title I of this Book shall be observed. In such a case the contract is called a suretyship. Section 4, Chapter 3, Title I, Book IV of the Civil Code states the law on joint and several obligations. When there are two or more debtors in one and the same obligation, the presumption is that the obligation is joint so that each of the debtors is liable only for a proportionate part of the debt. There is a solidary liability only when the obligation expressly so states, when the law so provides or when the nature of the obligation so requires. —Article 1207 of the New Civil Code. Traders Royal Bank v CA (Negotiable Instruments Law) TRADERS ROYAL BANK V CA G.R. No. 93397 March 3, 1997 FACTS: Filriters registered owner of Central Bank Certificate of Indebtedness (CBCI). Filriters transferred it to Philfinance by one of its officers without authorization from the company. Subsequently, Philfinance transferred same CBCI to Traders Royal Bank (TRB) under a repurchase agreement. When Philfinance failed to do so, The TRB tried to register in its name in the CBCI. The Central Bank did not want to recognize the transfer. Docketed as Civil Case No. 83-17966 in the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 32, the action was originally filed as a Petition for Mandamus 5 under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, to compel the Central Bank of the Philippines to register the transfer of the subject CBCI to petitioner Traders Royal Bank (TRB). DECISION OF LOWER COURTS: * RTC: transfer is null and void. * CA: The appellate court ruled that the subject CBCI is not a negotiable instrument. Philfinance acquired no title or rights under CBCI No. D891 which it could assign or transfer to Traders Royal Bank and which the latter can register with the Central Bank. Thus, the transfer of the instrument from Philfinance to TRB was merely an assignment, and is not governed by the negotiable instruments law. APPLICABLE LAWS: Under section 1 of Act no. 2031 an instrument to be negotiable must conform to the following requirements: (a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer; (b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money; (c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time; (d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and (e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated therein with reasonable certainty. Under section 3, Article V of Rules and Regulations Governing Central Bank Certificates of Indebtedness states that the assignment of registered certificates shall not be valid unless made at the office where the same have been issued and registered or at the Securities Servicing Department, Central Bank of the Philippines, and by the registered owner thereof, in person or by his representative, duly authorized in writing. For this purpose, the transferee may be designated as the representative of the registered owner. ISSUES & RULING: 1. Whether the CBCI is negotiable instrument or not. The pertinent portions of the subject CBCI read: xxx xxx xxx The Central Bank of the Philippines (the Bank) for value received, hereby promises to pay bearer, of if this Certificate of indebtedness be registered, to FILRITERS GUARANTY ASSURANCE CORPORATION, the registered owner hereof, the principal sum of FIVE HUNDRED THOUSAND PESOS. NO. The CBCI is not a negotiable instrument, since the instrument clearly stated that it was payable to Filriters, and the certificate lacked the words of negotiability which serve as an expression of consent that the instrument may be transferred by negotiation. Before the instruments become negotiable instruments, the instrument must conform to the requirements under the Negotiable Instrument Law. Otherwise instrument shall not bind the parties. 2. Whether the Assignment of registered certificate is valid or null and void. IT'S NULL AND VOID. Obviously the Assignment of certificate from Filriters to Philfinance was null and void. One of officers who signed the deed of assignment in behalf of Filriters did not have the necessary written authorization from the Board of Directors of Filriters. For lack of such authority the assignment is considered null and void. Clearly shown in the record is the fact that Philfinance's title over CBCI is defective since it acquired the instrument from Filriters fictitiously. Under 1409 of the Civil Code those contracts which are absolutely simulated or fictitious are considered void and inexistent from the beginning. Petitioner knew that Philfinance is not registered owner of the CBCI No. D891. The fact that a non-owner was disposing of the registered CBCI owned by another entity was a good reason for petitioner to verify of inquire as to the title Philfinance to dispose to the CBCI. OTHER NOTES: 1. the mere ownership by a single stockholder or by another corporation of all or nearly all of the capital stock of a corporation is not of itself a sufficient reason for disregarding the fiction of separate corporate personalities. RAUL SESBREÑO, petitioner, vs. HON. COURT OF APPEALS, DELTA MOTORS CORPORATION AND PILIPINAS BANK, respondents. G.R. No. 89252/ 222 SCRA 466 May 24, 1993 FACTS: Petitioner Raul Sesbreño made a money market placement in the amount of P300,000.00 with the Philippine Underwriters Finance Corporation ("Philfinance") with a term of 32 days. PhilFinance issued to Sesbreno the Certificate of Confirmation of Sale of a Delta Motor Corporation Promissory Note 2731, the Certificate of Securities Delivery Receipt indicating the sale of the note with notation that said security was in the custody of Pilipinas Bank, and postdated checks drawn against the Insular Bank of Asia and America for P304, 533.33 payable on 13 March 1981. Upon its maturity, petitioner sought to encash the postdated checks but they were dishonored for having insufficient funds. Petitioner then issued a demand letter to private respondent Pilipinas Bank, but the note was never released nor any instrument related thereto. Petitioner also made a written demand upon private respondent Delta as maker for the partial satisfaction of DMC PN No. 2731, explaining that Philfinance, as payee thereof, had assigned to him said Note. Delta, however, denied any liability to petitioner on the promissory note. As petitioner had failed to collect his investment and interest thereon, he filed an action for damages with the RTC against private respondents Delta and Pilipinas. The complaint was dismissed and was affirmed by the CA on appeal. ISSUE: WON a non-negotiable promissory note be assigned. RULING: Only an instrument qualifying as a negotiable instrument under the relevant statute may be negotiated either by indorsement thereof coupled with delivery or by delivery alone where the negotiable instrument is in bearer form. A negotiable instrument may, however, instead of being negotiated, also be assigned or transferred. The legal consequences of negotiation as distinguished from assignment of a negotiable instrument are, of course, different. A non- negotiable instrument may, obviously, not be negotiated; but it may be assigned or transferred, absent an express prohibition against assignment or transfer written in the face of the instrument. In this case, while the promissory note was marked "non-negotiable," it was not at the same time stamped "non-transferable" or "non-assignable." Hence, there is no stipulation which prohibited the promissory note’s assigning or transferring, in whole or in part. SERRANO VS CA (1991) Petition: Petition for Review Petitioner: Loreta Serrano Respondent: Court of Appeals and Long Life PawnShop, Inc. Ponencia: Feliciano, J. DOCTRINE: A pawn ticket is not a negotiable instrument. FACTS: 1. In March 1968, petitioner Loreta Serrano bought jewelry from Niceta Ribaya amounting to P48,500. 2. Serrano instructed Josefina Rocco, her private secretary to pawn the jewelry. 3. Rocco pledged the said jewelry for P22,000 to respondent Long Life Pawnshop, Inc. then escaped with the money. A pawn ticket was also issued for the said pieces of jewelry stating that it was redeemable "on presentation by the bearer." 4. Three months later, Serrano came to the knowledge that the pawnshop ticket for her jewelry was being sold. 5. Serrano went to the pawnshop and told the owner, Yu An Kiong not to permit anyone to redeem the jewelry as she was the lawful owner thereof. She also filed a complaint against Rocco with the police authorities and the latter also ordered the pawnshop to hold the jewelry and notify them in case someone redeems the same. 6. On 10 July 1968, Yu An Kiong permitted Tomasa de Leon, bearer of the pawnshop ticket, to redeem the jewelry. ISSUES: 1. Whether or not pawnshop is liable >Whether or not the pawn ticket is a negotiable instrument PROVISION: ACT NO. 203 - THE NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW OF THE PHILIPPINES Section 1. Form of negotiable instruments. - An instrument to be negotiable must conform to the following requirements: (a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer; (b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money; (c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time; (d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and (e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated therein with reasonable certainty. RULING + RATIO: 1. Yes Having been duly notified by Serrano and the authorities that the jewelry pawned to it was either stolen or involved in an embezzlement of the proceeds of the pledge, pawnbroker became duty bound to hold the things pledged and to give notice to petitioner and the police of any effort to redeem them. Although the pawn ticket stated that the pawn was redeemable by the bearer, it did not dissolve the duty of the pawnbroker to hold the thing pledged. The pawn ticket was not a negotiable instrument under the Negotiable Instruments Law nor a negotiable document of title under Articles 1507 et seq. of the Civil Code. DISPOSITION: The Petition is GRANTED. The Decision of the Court of Appeals dated 23 September 1976 is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The Decision of the Court of First Instance dated 22 May 1970 is hereby REINSTATED in toto. No pronouncement as to costs. BACHRACH V. GOLINGCO 39 PHIL 139 FACTS: Bachrach sold a truck to Golingco, which was secured by a promissory note and a chattel mortgage on the truck. The promissory note provided that there would be payment of 25% attorney’s fees. HELD: It may lawfully be stipulated in favor of the creditor that in the event that it becomes necessary, by reason of the delinquency of the debtor, to employ counsel to enforce payment of the obligation, a reasonable attorney’s fee shall be paid by the debtor, in addition to amount due of principal and interest. The legality of this stipulation, when annexed to the negotiable instrument, is recognized by the NIL. The courts have the power to limit the amount recoverable under a special provision in a promissory note, whereby the debtor obligates himself to pay a specified amount, or a certain per centum of the principal debt, in satisfaction of attorney’s fees for which the creditor would become liable in suing upon the note. *Normally, if there is absence of any agreement as to attorney’s fees, then the court would only grant nominal amounts. METROBANK vs. CA G.R. No. 88866 18 February 1991 Petition for review on certiorari J. Cruz FACTS: Eduardo Gomez opened an account with Golden Savings and Loan Association (Golden) and deposited 38 treasury warrants which total P1,755,228.37 [all were drawn by Philippine Fish Marketing Authority; 6 were directly payable to Gomez, others were indorsed by their respective payees]. On various dates (between 25 June to 16 July 1979) all the treasury warrants were subsequently indorsed by Gloria Castillo, a cashier at Golden, and deposited to the company’s Metrobank account. They were sent for clearing to the petitioner’s main office, which forwarded them to the Bureau of Treasury for special clearing. After repeated inquiries by their “valued client,” represented by Castillo, petitioner allowed the series of withdrawals (9, 13 & 16 July 1979), which totaled P968,000.00. In turn, Gomez was allowed to withdraw from his account with Golden (a total of P1,167,500.00) 21 July 1979 – petitioner informed Golden that 32 of the treasury warrants were dishonored by the Bureau of Treasury, and demanded the refund which was rejected. RTC: rendered judgment in favor of Golden. On motion for reconsideration, complaint was dismissed. CA: trial court decision was affirmed. ISSUE: Whether treasury warrants are negotiable instruments? HELD: No. CA decision AFFIRMED. RATIO: The Court held that the treasury warrants are non-negotiable instruments evident by the word “non-negotiable” stamped on its face, and it also indicates that they are payable from a particular fund, Fund 501. Sec. 3 of the NIL provides that an “order or promise to pay out of a particular fund is not unconditional.” The indication that the source of the payment (Fund 501) makes the order or promise to pay “not unconditional” and the warrants themselves non-negotiable. Petitioner cannot contend that by indorsing the warrants in general, Golden assumed that they were “genuine and in all respects what they purport to be,” in accordance with Sec. 66 of NIL. The simple reason is that this law is not applicable to non-negotiable treasury warrants. Castillo did not indorse them for the purpose of guaranteeing their genuineness but to deposit them with petitioner for clearing.