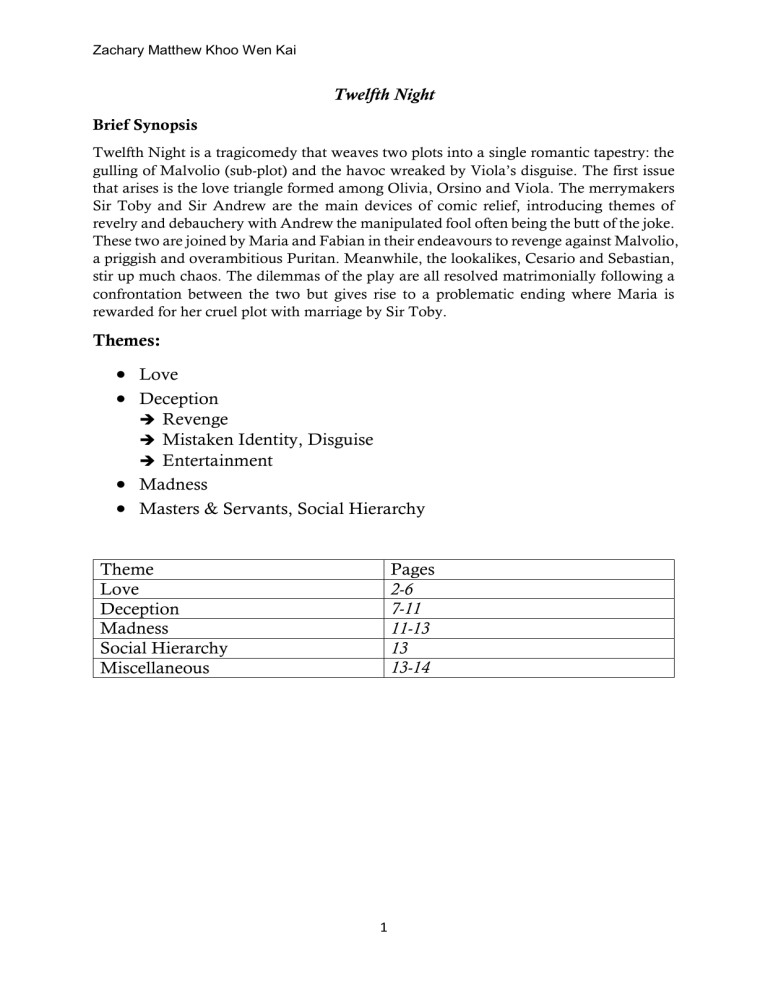

Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Twelfth Night Brief Synopsis Twelfth Night is a tragicomedy that weaves two plots into a single romantic tapestry: the gulling of Malvolio (sub-plot) and the havoc wreaked by Viola’s disguise. The first issue that arises is the love triangle formed among Olivia, Orsino and Viola. The merrymakers Sir Toby and Sir Andrew are the main devices of comic relief, introducing themes of revelry and debauchery with Andrew the manipulated fool often being the butt of the joke. These two are joined by Maria and Fabian in their endeavours to revenge against Malvolio, a priggish and overambitious Puritan. Meanwhile, the lookalikes, Cesario and Sebastian, stir up much chaos. The dilemmas of the play are all resolved matrimonially following a confrontation between the two but gives rise to a problematic ending where Maria is rewarded for her cruel plot with marriage by Sir Toby. Themes: Love Deception Revenge Mistaken Identity, Disguise Entertainment Madness Masters & Servants, Social Hierarchy Theme Love Deception Madness Social Hierarchy Miscellaneous Pages 2-6 7-11 11-13 13 13-14 1 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Love How is love portrayed to us? Folly of lovers (passions override reasons) Unrequited To be superficial/ have a transactional nature Self-indulgent/self-absorbed Blurring lines between love and service Debilitative effects of love; a foolish and agonising love that defies the logic of self-preservation Folly of Lovers Orsino Quote (Act 2.4): “tailor make thy doublet of changeable taffeta, for thy/mind is a very opal.” Point: Love is shown as unpredictable/volatile/fickle How is this shown: Clothing imagery and metaphor The Fool suggests that Orsino clads himself in iridescent garment that represents his opal-like character: he contradicts his own statements about love. Orsino critiques that women “lack retention./ Alas, their love may be called appetite,/ No motion of the liver, but the palate”. Here, he accuses women of being insincere and shallow in love. Yet, his opinion of women earlier on was that they are the foothold of men’s fancies, which “are more giddy and unfirm…sooner lost and worn”. He fails to adhere to one viewpoint on romance. This is an affirmation of Feste’s mocking exit speech, “and the tailor make thy doublet of changeable taffeta”. Feste’s parting words to Orsino in this scene satirize his capricious/mercurial behavior and deflate his pretense of “true love” for Olivia. Feste concludes by alluding Orsino’s fluidity in love to an opal, a gem which often abruptly changes colours. A comically inconstant character such as Orsino serves to accentuate the volatility of love and the many conflicting angles one may see it from. Quote (Act 1.1): “If music be the food of love, play on. / Give me excess of it, that surfeiting…Enough, no more. / ‘Tis not so sweet now as it was before.” Here, the Duke pouts about unrequited love. He indulges in sentimental music, declaring that if “If music be the food of love, play on. / Give me excess of it”. Orsino is determined to rid himself of his lovesickness by relishing melancholic melodies. However, seconds later, he impetuously grows tired of it and abruptly demands it be halted. He complains, “Tis not so sweet now as it was before”, ironically, moments after it had started playing. This reveals that he was keen on listening to music for its musical beauty to feed his passions, not to get sick of it. The juxtaposition of such contradictory behaviour meters the audience’s expectations of Orsino for the rest of the play. His flowery and unnecessarily dramatic language is also presented through phrases such as “surfeiting” and “dying fall”. Such affected gestures and extravagant manner of speech ridicule the convention of the Petrarchan lover who loves the fanciful idea of love more than his partner, producing much humor and fun. 2 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Selfless, Sacrificial Love: Olivia and Cesario Quote (Act 1.5): “Write loyal cantons of contemned love/ And sing them loud even in the dead of night;/ Hallow your (Olivia’s) name to the reverberate hills” Point: Love is portrayed mostly to be selfless and sacrificial beyond logic of self-preservation. Recall the allusion to Echo, a spurned nymph who lay longing for the exceedingly handsome Narcissus. Meanwhile, Narcissus was busy admiring his reflection in a stream and lay there too, turning a deaf ear to Echo’s calls. Both lay there until their bones wasted away. This Greek myth aptly presents the romantic struggle between Olivia and Cesario. In Act 1.5, Cesario declares he would, in melancholy pining, “Write loyal cantons of condemned love / And sing them loud even in the dead of night”. He would waste away until only his voice remains as he continues to “Hallow your (Olivia’s) name”. All the while, Olivia would be too self-indulgent to notice or care. Both characters lose themselves fixated on aimless love, showing how passion often overrides reason Between Orsino and Cesario Quote (Act 2.4): “Let concealment, like a worm i’ th’ bud/ Feed on her damask cheek” “sat like patience on a monument” Point: Unrequited love that is concealed shows to be self-destructive and largely irrational. Orsino tells Viola that women don’t know anything about what it is to love. Viola responds with a story brimming with dramatic irony. She tells of a woman who forbearingly hid her love for a man to the point where the emotional suffering gnawed away at her, giving her “a green and yellow melancholy”. The metaphor that surfaces here likens this scenario to a worm devouring a rose bud (young lady). The poor damsel in this story is actually Viola, who showcases her undying loyalty to an unknowing Orsino in this scene as she is letting “concealment, like a worm in a bud”, destroy her gradually, while she waits like “patience on a monument” Even when Orsino himself is unaware of it, Viola continues to care deeply for him, making sure not to snatch away his love for Olivia by professing her own, enduring the agony of keeping her love a secret, all the more when she knows that his love might not be sincere and heartfelt. Unrequited Love Orsino is spurned by Olivia Quote (Act 1.1): “If music be the food of love, play on. / Give me excess of it, that surfeiting, / The appetite may sicken and so die.” Point: Love is presented in an unrequited fashion that has debilitative effects on characters. In this scene, a languid Duke Orsino laments unrequited love. He is restless and enamoured of Olivia. An excess of music, he hopes, will abate his amorous desires and allow him to rise above this rejection. However, this turns out to be unsuccessful as Orsino finds the tunes to be “not so sweet now as it was before”. He maintains his melancholic posturing, preserving the woeful atmosphere by evoking metaphors of the sea. The oceans are vast, as is the Duke’s capacity for love (supposedly), but it is also “full of shapes” and causes anything “Of what validity and pitch so’er” to “fall into abatement and low price”. The 3 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai perpetually shifting mien of love upsets Orsino as it does not allow him to satiate his desires. Throughout most of the play, he drifts in such stasis: pining hopelessly for Olivia, and upon rejection, descending into sorrow and even spite. Then, he recuperates and the process repeats. Unrequited love entraps him in such a vicious cycle, taking a toll on his emotional wellbeing and preventing any positive character development. This is evident near the end of the play where he threatens Olivia, his alleged love object, with death: “Why should I not…kill what I love? ~A savage jealousy/ That sometimes savours nobly”. His mental decline is apparent; to the point where his destructive and possessive nature spurs him towards murder as a form of vengeance. Olivia is rejected by Cesario Quote (Act 1.5): “Love make his heart of flint that you shall love, / And let your fervor, like my master's, be / Placed in contempt.” Quote (Act 3.1): “I have one heart, one bosom, and one truth, / And that no woman has, nor never none / Shall mistress be of it, save I alone” Point: Love, in an unrequited manner, causes conflict internally and between characters. In Act 1.5, a disguised Viola visits Olivia’s household to, once again, profess Orsino’s love for her. Unfortunately, her showers of compliments and articulate speeches are met with another brisk rejection. Cesario, in his undying loyalty, feels anguish for Orsino. He curses Olivia before making a brusque exit, hoping that “Love make his heart of flint that you (Olivia) shall love, / And let your (Olivia’s) fervor, like my master's, be / Placed in contempt.” Olivia does not take offense at such a scolding, even from a lowly servant, only because she is infatuated with him. Surprisingly, Cesario’s vexing words come true in Act 3.1, where he spurns Olivia. The countess professes her love for him in a simple manner: “I love thee so”. In return, Cesario declares that “I have (He has) one heart, one bosom, and one truth, / And that no woman has, nor never none / Shall mistress be of it, save I (him) alone” This dramatically reveals that under the disguise of Cesario hides a lady, but Olivia is too upset by rejection to notice. Clearly, the pains of unrequited love have given rise to tension between characters. Following this chain of events, too, is the formation of a difficult love triangle where Viola, Orsino and Olivia all experience unreciprocated love and pine for one another. This, in turn, creates internal conflict within Viola, who must help her love object, Orsino, pursue another woman, while she painstakingly hides her love for him. Superficial, Transactional Nature Olivia Quote (Act 3.4): “For youth is bought more oft than begg’d or borrow’d” Quote (Act 3.4): “Here, wear this jewel for me, 'tis my picture…And I beseech you come again tomorrow” Point: Love is portrayed to have a salient transactional nature. Olivia is the play’s main proponent of transactional love. In Act 3.4, she makes plans to entertain Cesario and, to avoid debasing her social status, produces a jewelled necklace as a gift in the belief that “youth is bought more oft than begg’d or borrow’d”. Here, the recurring idea of purchasing one’s love surfaces. 4 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Later, just before Cesario departs, Olivia offers him that ornament: “Here, wear this jewel for me, 'tis my picture…And I beseech you come again to-morrow”. This also falls in line with her ploy in Act 2.2, where she delivered a ring to Cesario in the hopes that he would return to her. It is important to note that instead of using rationale and debate to try persuading Cesario to revisit her, Olivia resorts to gifts without a second thought. Hence, her withdrawal into the transactional nature of love is plainly shown through the two aforementioned events. Unfortunately, Cesario’s unconditional servitude for Orsino is not moved by such materialism. Self-indulgence Orsino Quote (Act 1.1): “She purged the air of pestilence” Quote (Act 1.1): “And my desires, like fell and cruel hounds, / E’er since pursue me” Point: Orsino portrays himself to be exceedingly self-absorbed/vain OR Love is shown through comical self-indulgence. In this scene, Orsino rhapsodizes about his love object, Olivia. He is lost in highsounding hyperboles, claiming that “She purged the air of pestilence”. Olivia is likened to a gorgeous, chaste goddess who is so pure that she cleansed the air of disease and dirtiness. Then, Orsino’s train of thought abruptly ends. He stops exalting Olivia and suddenly raises similes of Greek mythology. Forcing himself back under the limelight, he sighs, “And my desires, like fell and cruel hounds, / E’er since pursue me”. It is obvious that Orsino alludes to the hunter Actaeon only to bring himself to the centre of attention once again. In fact, his metaphor is symbolic of his desires that destroy him in time to come. This is because, if only he dropped his egocentric indulgence, he would have been able to properly devote time and energy to wooing Olivia instead of glorifying himself every other minute. Quote (Act 2.4): “There is no woman’s sides / Can bide the beating of so strong a passion / As love doth give my heart.” Quote (Act 2.4): “Of your complexion” “About your years” Possible Point: Orsino exhibits a certain immaturity in his behaviour. In a colloquy between Orsino and Cesario, they discuss love and eventually touch upon the topic of Olivia rejecting Orsino. Out of desperation and bitterness, the Duke addresses women scornfully: “There is no woman’s sides / Can bide the beating of so strong a passion / As love doth give my heart.” It becomes obvious how despaired Orsino feels, as he was completely oblivious to Cesario’s overt hints at “his” love for him; when he inquired about Cesario’s love object, Cesario told him that she was “of your (his) complexion” and “about your (his) years”. There was barely any reason for Orsino to be as upset as he was. Interestingly, he was actually unable to accept that the woman he adores refuses to reciprocate his love. He adamantly believes that a love “of so strong a passion” as his would engulf any woman. This, in fact, is a show of his childish character. Orsino displays such a level of ignorance and obstinance that connotes immaturity. 5 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Malvolio Quote (Act 3.4): “go to bed” “To bed! ay, sweet-heart, and I'll come to thee” Quote (Act 3.4): “nightingales answer daws.” Quote (Act 3.4): “fellow! not Malvolio, nor after my degree, but fellow” Quote (Act 3.4): “are idle shallow things; I am / not of your element” Point: Self-love/self-indulgence is depicted as leading to excessive levels of delusion and ignorance. In Act 3.4, Malvolio attempts to actualise his heady dreams of being “Count Malvolio”. He indulges in self-perceived greatness and is so deluded that he deliberately misinterprets others’ words to suit his fancy and puts himself above his fellow servants and even Sirs Toby and Andrew. When Olivia advises Malvolio to “go to bed” and rest, he lewdly interprets this as a sexual invitation to “go to bed” with Olivia. He responds while smiling madly, “ay, sweet-heart, and I’ll come to thee”. This likely evoked laughter from the audience as the other characters grew more disconcerted by Malvolio’s unusually foolish manner. Another show of Malvolio’s disillusion appears when Olivia addresses him as a “fellow”. Although she was referring to him as a common servant, he exclaims, “fellow! not Malvolio, nor after my degree, but fellow”. Perhaps, he interprets “fellow” as “friend”. To add to the delirium, Malvolio cannot wait to realise his social ambition and acts out of place. When Maria greets him, he scoffs condescendingly that “nightingales answer daws”. All of a sudden, Malvolio is an elegant Nightingale in his eyes while Maria is a graceless, croaking daw even though they are of equal social status. His inflated self-importance only grows disproportionately from this point. Later on, he even chides aristocrats. He says that Sir Toby and Andrew “are idle shallow things” and that he is “not of your (their) element”. The recurring idea of selfdeception surfaces once more here. Blurred boundaries between love and service Quote (Act 5.1): “sacrifice the lamb” “To do you rest, a thousand deaths would die” “After him I love…more than my life” Point: The boundaries between love and service are blurred, especially towards the later Acts. In Act 5.1, just when matters were settling down, Olivia recalls proof of Cesario’s marriage with her, and confusion mounts to a higher crescendo. Cesario is accused of alienating Olivia’s affections from Orsino. Upon hearing this, the Duke flies into a rage, shown by his rave on how in his “spite”, he would “sacrifice the lamb” that he loves just to wreak vengeance upon Olivia. Even through this, Cesario’s servility is undeterred. “He” affirms Orsino that he would bear “a thousand deaths” if it could ease Orsino’s pain, revealing “his” selflessness in his servitude. Cesario simply wishes for the best for Orsino, and after all he’s done, he would give up her life and any opportunity to marry him just to bring him peace. This exemplifies how Cesario puts Orsino’s interests far above his own. Despite being wrongly accused, Viola still declares that she loves Orsino “more than my (her) life”. This unbelievable level of loyalty is obviously bordering on love. As a servant, Cesario is only bound to Orsino’s instructions and “his” duty stretches no further. Yet “he” would go as far as to sacrifice his life for the fickle Orsino’s momentary happiness. 6 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Deception What forms does Deception take? Self Revenge Disguise, Mistaken Identity Entertainment Self Malvolio (Reuse point on self-indulgent love as: self-deception) Revenge Malvolio Quote (Act 2.5): “To be Count Malvolio!” Quote (Act 2.5): “Be opposite with a kinsman, surly with servants” “Remember…thy yellow stockings” “See thee cross-gartered” Quote (Act 2.5): “I do not now fool myself, to let imagination jade me” Quote (Act 2.5): “afraid of greatness” “steward still” Point: Deception is presented as a means to execute revenge. Twelfth Night’s comic subplot revolves around the duping of Malvolio. It opens with a cunning episode of deception in Act 2.5. Here, Malvolio is preoccupied with self-interest and aspires to gain authority through social inversion just so he can rile others as “Count Malvolio” without retribution. Such a preoccupation leaves him vulnerable to manipulation in pursuit of his desires. Thus, Maria’s ploy spins into action as he walks right upon her “love note”. Maria’s familiarity with Olivia’s mannerisms, dislikes and even handwriting allows her to craft a convincing letter. Along with this, Malvolio’s conceit about himself makes it easy to tempt him into ridiculous behaviour. The letter instructs him not to be “afraid of greatness” (which he dearly craves) and that, to achieve greatness, he must “Be opposite with a kinsman, surly with servants”. Such acts of misrule contradict Malvolio’s puritanical convention, but he is so wrapped up in his secret desire for social advancement that he complies anyway. Moreover, he is advised to don “thy (his) yellow stockings” or be thought of as no more than a “steward still”. Such an obvious device would never have succeeded if not for Malvolio’s excessive power-hungriness. The fact of the matter is that Olivia detests the colour yellow, which was also an Elizabethan symbol of jealousy. She also abhors cross-gartering, a fashion of dress meant only for the lowest menials. To add to the humour here, Malvolio ironically thinks he can woo a countess in such an outrageous costume! There is even a certain irony when he exclaims in joy, “I do not now fool myself, to let imagination jade me” for this is very much a product of his fantasies. Hence, Maria displays exquisite shrewdness in forging a letter of apologetic modesty, with tones of anonymous, tender love that stir up Malvolio’s egotism. He is the most at odds with the comic spirit of the play, so Maria and friends make full use of deception to attain their revenge and humiliate him. 7 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Malvolio & Feste Quote (Act 5.1): “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you” Quote (Act 5.1): “The whirligig of time brings in his revenges” Point: Revenge is shown to have a cyclical nature. Disliking Malvolio’s sour disposition and officious nature, Maria and company seek to humiliate him, manipulating his ego since “the vice in him” gives the device a “notable cause to work”. His torture is extremely ruthless, only targeting this crippling weakness, repeatedly mocking him as a “madman” and a “foul collier”, showing how hellbent the trio are on exacting revenge, bombarding Malvolio to exploit his emotional vulnerability. Upon discovering the plot against him, Malvolio also becomes engulfed in rage, announcing to the party that he would be “revenged on the whole pack” of them The abruptness of his exit brings a sense of continuity to his words, showing how even after the event, revenge will continue. Malvolio even neglects the presence of nobles, including Olivia, the woman he had so desired to marry, and speaks disrespectfully and rashly, showing how he holds much weight to his words. This is pointed out by Feste, stating that this revenge had been brought by the “whirligig of time”, suggesting that the cycle of revenge is never-ending, and will continue as surely as time goes round. Such a cyclical nature even proves to be ironic, as Malvolio’s bitterness and conceit is what got him into such a spot in the first place. Yet, he retains this posturing throughout the play and refuses to see why he is detested so. Disguise Viola Quote (Act 1.2): “Conceal me what I am” “mind that suits… thy fair and outward character.” Quote (Act 1.2): “What else may hap to time I will commit” Quote (Act 1.4): “Yet, a barful strife / Whoe'er I woo, myself would be his wife.” Quote (Act 2.2): “Disguise, I see thou art a wickedness, / Wherein the pregnant enemy does much” Point: Deception, in the form of disguise, turns out to be a necessary evil for the play to progress. Shipwrecked on a mysterious island, Viola must “conceal me (her) what I am (she is)”. This was especially important in Elizabethan times, where the highly misogynistic social hierarchy, “Great Chain of Being”, dictated that women were inferior to men in every rank. Moreover, female peasants were considered to be the least of people, just above animals. If Viola wanted to secure her future, she needed to pose as a man to avoid social alienation as a virgin maiden. Furthermore, she was headed to serve under Duke Orsino, who is often seen holding a demeaning attitude towards women; he treats them “as roses”: there is nothing to them other than their fleeting beauty. It is interesting to note that, in Act 1.2, Viola first trusts the Sea Captain because he is not disguised; she believes his “fair behaviour” is a sign of his “mind that suits… thy (his) fair and outward character.” This implies that a lack of disguise is trustworthy and that disguise is therefore possibly treacherous. Here, Shakespeare establishes the paradox of Viola’s position: disguise suggests dishonesty, yet she gains access to Illyrian society through disguise. 8 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai The dicey consequences of disguise emerge later, when Viola is placed in an emotionally agonising situation. She realises that “Whoe'er I (she) woo(s), myself (herself) would be his (Orsino’s) wife.” Although she dearly loves Orsino, her empathetic nature and servility causes her to continue helping her love object pursue another woman. Then, when Viola realises that Olivia in turn pines for her, she “see(s) thou art (disguise) a wickedness”, as her male persona completes a difficult love triangle between her, Orsino and Olivia. Thus, while disguise is absolutely necessary for Viola, it also proves problematic for her in various ways. Mistaken Identity Overarching Point: Mistaken Identity is used to enhance dramatic irony for comedic effect. Antonio & Cesario Quote (Act 3.4): “If this young gentleman / Have done offence, I take the fault on me” Quote (Act 3.4): “What will you do, now my necessity / Makes me ask you for my purse?” Quote (Act 3.4): “What money, sir?” Quote (Act 3.4): “I know of none, nor know I you by voice or any feature”. Point: Disguise inadvertently causes conflict through mistaken identity. Both Antonio and Cesario become disoriented in one of many scenes of mistaken identity here. Cesario must have been giddy with emotion: first, “he” was forcefully challenged by Sir Andrew to a duel. “He” was petrified that his female identity would be compromised, as the noblewoman in disguise knew nothing of swordsmanship or combat as an Elizabethan gentleman should. Then, relief washes over him as Antonio intervenes, declaring that “If this young gentleman / Have done offence, I take the fault on me”. Alas, this relief is replaced by confusion as Antonio, who is a stranger to Cesario, turns him and asks, “What will you do, now my necessity / Makes me ask you for my purse?”. Naturally, Cesario responds in incertitude: “What money, sir?” This perceived ingratitude enrages Antonio, who believes he is talking to Sebastian. He denounces Cesario’s disloyal attitude, while ‘he’ remains in denial as ‘he’ “know(s) of none, nor know I you (Cesario Antonio) by voice or any feature”. Such disarray escalates until Antonio is escorted away by two officers of Orsino. Thus, an unfortunate incident of mistaken identity ended up in Antonio feeling betrayed, Cesario’s reputation tainted and the friendship between Antonio and Sebastian strained. Sebastian versus the entire Cast Quote (Act 4.1): “Nothing that is so, is so.” Quote (Act 4.1): “foolish Greek” “vent thy folly somewhere else” “this great lubber, the world, will prove a cockney” Quote (Act 4.1): “Ungracious wretch, / Fit for the mountains and barbarous caves” Quote (Act 4.1): “He started one poor heart of mine, in thee” Point: Disguise stirs up chaos through mistaken identity. Sebastian’s world descends into pandemonium as he is bombarded by nearly every character in the play. From invitations to Olivia’s household to physical assault to 9 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai proposals of marriage, he lives through multitudes of madness in a matter of minutes. This scene brims with the comedy of mistaken identity, which is aptly summed up by Feste: “Nothing that is so, is so”. First, Feste beckons to Sebastian to follow him back to Olivia’s palace, under the impression that he’s speaking to Cesario. Sebastian shakes the stranger off, asking the “foolish Greek” to “vent thy (his) folly somewhere else”. Incensed by “Cesario’s” sudden dismissiveness, Feste rants how “This great lubber, the world, will prove a cockney”. Then, Sir Toby and Andrew arrive. Sir Andrew mistakes Sebastian for Cesario, of course, lunging at him in a show of bravery. Sebastian is taken aback at having been attacked by a stranger, exclaiming, “Are all the people mad?”. Being a true swordsman, he returns Sir Andrew’s blows ruthlessly. Sir Toby swiftly intervenes, restraining him from further injuring the whimpering Sir Andrew. The two struggle until Olivia arrives. This opens yet another episode of anarchy, as the Countess berates Sir Toby for acting rashly towards “Cesario”. At long last, her true colours come to light as she calls Belch an “Ungracious wretch, / Fit for the mountains and barbarous caves”. Next, the noblewoman turns to Sebastian and, to his shock, starts flirting with him, “He (Belch) started one poor heart of mine (Olivia) in thee (Sebastian)”. At this point, Sebastian’s doubt of his own sanity is understandable. Hence, the main characters of the play become extremely puzzled at “Cesario’s” shunning of them, while Sebastian witnesses lunacy take place as strangers on a mysterious island insist that they know him. Entertainment Sir Andrew Quote (Act 3.2): “dear venom” Quote (Act 3.2): “unless you do redeem it by some laudable attempt either of valour or policy.” “no way but this” Quote (Act 3.2): “though thou write with a goose-pen” “a dear manikin to you” Point: Deception is shown to be used as a cruel form of entertainment. In Act 3.2, Sir Toby and Fabian collaborate to gull Sir Andrew simply for their amusement. They goad him into a swordfight, and their words are riddled with sarcasm that the laughably slow-witted Andrew fails to pick up on. While seemingly showering him with praise, Belch and Fabian’s compliments take sly digs at Sir Andrew’s cowardice and naïveté. The most humor comes from the fact that Andrew is genuinely spurred on by their lauding, oblivious to their hidden meanings. To get the ball rolling, Sir Toby calls him “dear venom”, a seemingly flattering name. However, it is actually a sarcastic gibe at Sir Andrew’s infirmity and lack of courage. While venom connotes something poisonous, potent and effectively lethal, the audience is aware that Sir Andrew is the exact opposite of this, creating much irony and humor. It is important to note that, up until this point, Sir Andrew was struggling to win the affections of Olivia. Fabian exploits this desperation by suggesting that he “redeem it (her love) by some laudable attempt either of valour or policy”. This is where the scheme to humiliate Sir Andrew culminates. Sir Toby and Fabian even disillusion 10 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai him into believing that challenging Cesario to a duel is his only avenue to winning Olivia’s heart by declaring that there is “no way but this”. It is clear that Sir Andrew is being sorely manipulated and deceived by his “friends” for their enjoyment. He is also very foolish to think that Olivia would fall for someone as unattractive and, as he says himself, uneducated in the arts. Along the way, more taunts are sneaked into the dialogue between the three. Sir Toby edges Sir Andrew on to write an aggressive letter to Cesario “though thou (he) write with a goose-pen”. It is an implicit insult towards Sir Andrew, as the goose was largely seen as a symbol of cowardice. Still, such depreciation goes undetected by Sir Andrew who thinks that they continue to praise him and persists in his daydreams of Olivia. “Madness” What causes Madness to appear in Twelfth Night? Conflicting or mistaken perceptions Passions overriding reason Uproarious, unbridled ribaldry and revelry Purpose of Madness (Additional Context): With Twelfth Night comes a brief celebratory period of social inversion, brimming with rowdy merrymaking and feasting that marks the coming of the Epiphany. On this special eve, the world is thrown topsy-turvy, and the people seem to enjoy the chaos that comes with reversal of social hierarchy. Many got to live as royalty for a day, no matter their actual social status. As people were euphoric and places were rife with confusion and incongruity, there was bound to be a certain madness coursing through the masses. This madness is exaggerated and hence very much present in Twelfth Night. It is important to note that “madness” here does not signify mental illness, but rather the tossing out of civility. Such partying may be seen as senseless and hence mad. Madness also has several uses throughout the play. It is mainly used entertainingly; to make a fool of characters and produce comic effect. Clashing Perceptions May refer to point of Mistaken Identity on Sebastian for additional point. Orsino & Antonio Quote (Act 5.1): “I saved my life and gave him my love” Quote (Act 5.1): “Today, my lord, and for three months before… did we keep company” Quote (Act 5.1): “Fellow, thy words are madness” Point: Madness appears to arise from clashing perspectives of the same issue. Here, an infuriated Antonio storms into the Duke’s palace, though restrained by several Officers. He lambasts Cesario who stands stupefied by Orsino’s side, claiming that “I (he) saved my (Cesario’s) life and gave him my (Cesario his) love”. Antonio also complains that “for three months before…did we (him and Cesario) keep company” before Cesario betrayed him. Of course, Orsino is astonished that his loyal servant, having never left the palace except to deliver messages, has somehow been travelling alongside an infamous pirate all this while. 11 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai However, what Orsino fails to realise is that Antonio is referring to Sebastian in the past and Cesario at present, while Orsino believes that he is only talking about Cesario. He decides that, as Cesario has mostly been by his side these three months, Antonio’s tales are nonsense. Before dismissing Antonio, Orsino turns to him and quite brusquely says, “Fellow, thy words are madness”. Orsino thinks of Antonio as spewing madness. On the other hand, Antonio has given quite an accurate report on his dealings with Sebastian and Viola in her role as Cesario. Both are simply mistaken as to what the other is talking about. Thus, two conflicting viewpoints of the same matter lead to an illusory sense of madness, as two characters claim that vastly different and hence contradictory events transpired at the same time. Passions Overriding Reason Orsino Quote (Act 5.1): “to the Egyptian thief at point of death, / Kill what I love?” Quote (Act 5.1): “savage jealousy” Quote (Act 5.1): “thine own trip shall be thine overthrow” Point: Madness seems to surface when characters allow their romantic passions to overcome all sense of reason. In this scene, Orsino believes that Cesario, who is well aware of his love for Olivia, hoodwinked him and married the Countess himself. Confusion surmounts here, as it is in fact Sebastian who vowed to Olivia matrimonially; Orsino is unaware of this. Cesario, in turn, is stunned by Olivia’s claims and Orsino’s fury. The Duke feels betrayed and, in his anger, murderously threatens “to the Egyptian thief at point of death, / Kill what I love (he loves)”. This line is doubly ironic and intriguing as it is perhaps the first time that the audience witnesses Orsino lose his composure and fly into a rage. Earlier on, Orsino labels Antonio derisively as a thief, yet he is now naming himself the same things. This is the first instance of irony in his statement. Second, his allusion of himself to a thief undercuts his noble status and self-importance; something he treasures. Furthermore, he calls such a revenge “a savage jealousy”, admitting that he has succumbed to employing ignoble and ruffian tactics to get his way. Moreover, he curses Viola that “thine own trip shall be thine overthrow” when he loved her dearly before. Hence, Orsino loses some rationale of thought when he undermines his nobility and contradicts his earlier statements. He also abruptly switches his melancholic, fanciful persona to a bloodthirsty one. Clearly, his impassioned love has preceded his logic and driven him to the edge of madness. Revelry, Ribaldry Maria & Friends vs Malvolio Quote (Act 2.3): “Not to be abed after midnight is to be up betimes, and diluculo surgere” Quote (Act 2.3): “A stoup of wine, Maria!” Quote (Act 2.3): “My masters, are you mad? Or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty…?’’ 12 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Point: Excessive merrymaking may be perceived as madness to some in the play. Here, Maria and the gang have light-hearted, drunken fun, singing to their hearts’ content and debating in inebriated seriousness. However, their festivity will later come to a halt when Malvolio enters and so much as demeans their sanity for partying so loudly late into the night. Sir Toby claims that “Not to be abed after midnight is to be up betimes, and diluculo surgere”. He uses the Latin proverb in a rather perverse way; it means that rising early is healthy. Yet, Sir Toby ironically recalls it to justify not going to bed at all. This contradictory quarrel over bedtimes goes back and forth between the two drunken Knights until Sir Toby calls for yet another “stoup of wine”. A stoup connotes a very wide flagon to contain drink, rather than a cup or glass. Therefore, to add to the merrymaking, the crew now drinks uncurbed amounts of alcohol that throws things even more topsy-turvy on top of it all. Then, Malvolio arrives and questions his masters, “are you (they) mad?” Clearly, he has an aversion to their behaviour and even pompously declares that the group has “no wit, manners, nor honesty”. Such a blatant insult at their intellect and behaviour shows that the steward strongly views festivity as madness. Perhaps, the tossing out of civility in place of ludicrous amounts of festivity may be seen as a step towards insanity. Thus, this is another instance of how characters may view madness in Twelfth Night. *One of the subplots of the play concerns Malvolio and the prank played on him. He is tricked by Maria’s plan to humiliate him and believes that Olivia is in love with him, and he does what the forged letter says. He creates large amounts of revelry at Olivia’s party. He shows up dressed like a clown, smiling, and insulting everybody. He acts in such a way as to seem insane to people not knowing to the plot to humiliate him. The way he acts ironically pushes Olivia farther and farther away from him. Even when she wants to get to know him better, the way he acts and the way he dresses at this point in the play only serves to stop him from achieving his unfounded goal. This insanity is revelry. The motivation behind Maria appears to be revenge, but everyone else involved in the prank are in it for the entertainment. Ironically, Malvolio is the strictest of the characters and is the one trying to shut down all the merrymaking. He gets twisted around to the opposite of his character during the prank. Masters and Servants, Social Hierarchy Comments on this Theme: Basis of Twelfth Night is Social Inversion (refer to Madness) Malvolio strives to climb the social pyramid Masters (Olivia) heed Servants (Cesario) with respect, seen in informal pronouns Masters sully their social status by wooing Servants Servants selflessly sacrifice for their Masters (refer to Love) 13 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Character Analyses *Asterisk-marked traits can already be evidenced from quotation notes Viola Character Traits: Selfless*, Loyal & duty-bound*, Resourceful*, Quick-witted/silver-tongued Quick-witted: Refer to Viola’s speech from Act 1.5. Emphasize how, her eloquence and intellect allow her to be discourteous and to transgress lines between master and servant, yet still be in her masters’ favours. She crafts an impassioned speech that wins Olivia’s affections, so Olivia forgives that Viola engaged in a somewhat disrespectful, brief verbal spar with her prior to her speech such that Olivia acknowledges her “courtesy…is so fearful”. *She flaunts her resourcefulness already in her first entrance in the play, being of sound judgement to recognize the Captain’s integrity and thus trust him, inventive enough to create a convincing disguise and practical enough to carry out this disguise, initially for her own wellbeing. Masculinity is also poked fun at and caricatured through her character in her assuming her identity as the boy servant/messenger Cesario as seen in her overemphatic courtesies and hyperbolic professions towards Olivia, revealing Orsino’s courtship as silly and comical. Orsino Character traits: Petrarchan lover/self-indulgent*, fickle*, immature* Immature: Refer back to Page 5 on how he is unable to accept that a woman is simply not enamoured by his superficial character and ‘true love’. *Orsino and Olivia are worth discussing together, because they have similar personalities. Both claim to be buffeted by strong emotions, but both ultimately seem to be self-indulgent individuals who enjoy melodrama and self-involvement more than anything. When we first meet them, Orsino is pining away for love of Olivia, while Olivia pines away for her dead brother. They show no interest in relating to the outside world, preferring to lock themselves up with their sorrows and mope around their homes. Olivia Character Traits: Transgressive of social norms, Excessive/ melodramatic, Caring Transgressive: According to traditional Elizabethan notions of gender, the "ideal" woman is supposed to be silent, chaste, and obedient. Olivia shatters the stereotypical role she's been assigned to when she aggressively pursues Cesario’s affections and asks for “Cesario’s” (Sebastian’s) “full assurance of your (his) faith”, or his hand in marriage. She also breaks from the idea that she should marry a man of similar age and social status when she 14 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai pursues a young servant. All these controversial decisions make Olivia just as unruly and rebellious as figures such as Toby Belch and Feste. Her behaviour, then, is a significant part of the play's topsy-turvy spirit. Excessive: When the play opens, Olivia is in deep mourning for her dead brother. She grieves “like a cloistress, she will veiled walk”, residing in solitude and weeping every day for 7 years. Shakespeare exaggerates her vows and makes it clear that her behaviour is rather ridiculous. Perhaps, this mocks her melodramatic nature and the convention of indulgent Petrarchan love. Moreover, Olivia's tears are compared to a "brine" that "seasons" her "brother's dead love" Interestingly, Olivia's tears are compared to pickle juice, folks. This somewhat likens her to a pickle-maker, which in turn makes her late brother a pickled cucumber. Such a laughable allusion further serves to ridicule her disproportionate vows. Even Feste goes out of his way to demonstrate the folly of Olivia's behaviour when he says in an argument that she is “the more fool” to mourn for her brother. Her sombre demeanour is also jarring in contrast to play's festive atmosphere, which is conspicuous in light of the fact that Olivia's house guests party all night while she traipses around her chamber weeping. Caring: We can see her benign nature in the fact that, despite wanting to reject all society to mourn, she permits Sir Toby and Sir Andrew to remain as guests. This is in spite of her strong objection to Sir Toby's drunkenness and rowdiness. Such aversion to their late-night revelry expressed through Maria who declares to Sir Toby, "By my troth…your cousin, my lady takes great exceptions to your ill hours”. However, regardless of how much Olivia disapproves of Sir Toby's persistent behaviour, she continues to tolerate his presence so he has a place to stay, showing just what a caring and nurturing nature she has. Also, in response to Malvolio’s sudden madness, she also kindly advises him to “go to bed” and continues to be somewhat patient with his perturbing behaviour, only wishing that he recovers fully in time to come. Malvolio Character Traits: Self-loving*, Arrogant*, Hypocritical Arrogant: Refer to Madness where he calls his masters mad. This highlights his feelings of superiority over the group, despite him being inferior hierarchically, such that he can be so discourteous towards them. This also prompts Sir Toby to respond patronisingly to remind Malvolio that he is not “any more than a steward”. Hypocritical: Following the inversive nature of the play, Malvolio plays into the carnivalesque idea of role reversal. The way in which Malvolio’s previously haughty and abrasive character is transformed into a soft and sycophantic one, constantly begging “Sir Topas, good Sir Topas” and later, Feste in his own habit, calling him the “good fool” brings much humor to the subplot. Where Malvolio once scorned and insulted Feste, saying how he “marvels (Olivia) can take delight in such a fool”, he now begs at the feet of him, showing how the hegemonic social structure of Illyria has been subverted. There is also a certain irony in how Malvolio turns out to be the true fool, smiling like a madman and dressing 15 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai incredulously in vain attempts to woo Olivia. He capers around in “yellow stockings” and his once stiff and joyless demeanour turns merry and idiotic, showing how his social ambition has overcome his good sense. Indeed, he hypocritically fails to abide by the principle of order he preaches as long as it is in the name of love. Maria Character Traits: Crafty Crafty: Maria displays exquisite shrewdness in forging a letter of apologetic modesty, with tones of anonymous, tender love that stir up Malvolio’s egotism. Her familiarity with Olivia’s mannerisms, dislikes and even handwriting also allows her to craft a convincing letter. As expected, Malvolio takes the bait and her ploy spins right into action. It follows through, and her unilaterally crafted scheme works perfectly in convincing Olivia of Malvolio’s madness. Sir Toby even claims that he “could marry this wench for this device”, and indeed he does in the final Act, sullying his social status just to reward Maria for such an ingenious prank. Moreover, Maria is praised and likened to “Penthesilea”, a mythical Amazonian queen admired for her wisdom. These instances show how resourceful Maria is, and her ease in coming up with a masterful plot. Sir Andrew Character Traits: Gullible*, Poorly educated/unsophisticated, Vain Unsophisticated: (Refer to Madness) Sir Andrew often simply imitates others, repeating the lines of his “friend”, Sir Toby, or spews nonsense in attempts to participate in discussions. One example of this is when Sir Toby quotes the Latin proverb, “Diluculo sugere”, to which Sir Andrew responds, “to be up late is to be up late”. He likely finds Sir Toby’s reference incomprehensible and tries to make his own intellectual remark by repeating the phrase “be up late”, ending up saying gibberish. This implies his inability to keep up with the others and lack of education. Furthermore, when Sir Toby tells him to “accost” Maria, Sir Andrew addresses her as “Good Mistress Accost”. Such a brainless move early on in the play sets the tone for Sir Andrew’s stupidity and his tendency to take things literally or misinterpret them ridiculously. Lastly, Sir Andrew even claims that while Sir Toby’s foolish behaviour is practiced, folly comes to him “more natural”. This is heavily ironic, as Sir Andrew unwittingly admits that his foolishness is inborn, and even fails to spot his selfdeprecation. Vain: Sir Andrew is easily flattered, which also ties in to his naivete. When lamenting Olivia’s preference for Orsino over him, Sir Toby praises him in a backhanded manner: “She’ll (Olivia will) not match above her degree, neither in estate, years, nor wit”. In other words, since she is not eyeing anyone too smart or competent, Sir Andrew has a chance with her. Such an overt insult is missed by Sir Andrew, and he is wholly pacified by Sir Toby’s remark. Sir Toby 16 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai Character Traits: Manipulative/deceptive*, of Noble birth but boorish; ignoble, Hedonistic Hedonistic: (Refer to point on Madness for alcoholism) Sir Toby is a glutton and is usually inebriated whenever he makes an entrance. His surname, Belch, also heavily suggests his drinking habits since he needs to belch so often. Furthermore, he declares that he will “drink to her (Olivia) as long as there is passage in my (his) throat”. As mentioned above, he will even leech money off his unknowing “friend’, Sir Andrew and continually lie to him in order to preserve his regular indulgence in alcohol which obviously gives him much pleasure. Ignoble: Despite being a member of nobility, Sir Toby proves to be quite ignoble in his manners. He has no issue offending others and, as aforementioned, is willing to engage in deceit to get what he wants. Sir Toby also makes crass jokes and is a fervent alcoholic, which clearly does not put him in a good light, especially in his drunkenness. His crude behaviour is even hinted to the audience through his use of verse, the casual everyday style of speech used by menials, instead of the elegant prose that the other aristocrats often speak in. One example of a sexual innuendo that Sir Toby cracks is in his critiquing of Sir Andrew’s hair. He claims that “it hangs like flax on a distaff” and he hopes “to see a housewife take thee (Sir Andrew) between her legs”. This is a vulgar reference to the sexual disease, syphilis and obviously, sex. Miscellaneous Characters: Sebastian *Sebastian plays a critical role in first complicating, and then resolving the central conflict, even though we know little about his feelings or motivations. After surviving the shipwreck with the help of Antonio, Sebastian has no clear purpose or plan, but decides he is “bound to the Count Orsino’s court” (2.1.). However, everyone he encounters mistakes him for Cesario, leading Sebastian to wonder “Are all the people mad?” (4.1.). When Olivia greets Sebastian warmly, he is confused but also pleased that a beautiful and wealthy woman is treating him so nicely. As he reflects, “If it be thus to dream, still let me sleep!” (4.1.). Sebastian passively goes along with the curious circumstances unfolding around him; he doesn’t seem inclined to ask too many questions. The experience of surviving the shipwreck seems to have left him open to accepting whatever fate unfolds for him. Once he has been happily reunited with his sister, there is little left for Sebastian to do. Sebastian is the catalyst for the play’s resolution but offers very little by way of action to achieve that resolution. Antonio *Antonio is an enigmatic character in the play who heightens the main themes. He first appears imploring Sebastian to either stay with him longer or allow him to accompany the younger man when he leaves. Antonio is quite dramatic in the language he uses, imploring, “If you will not murder me for my love, let me be your servant” (2.1.). Additionally, even though it is dangerous for him to go to Orsino’s court, Antonio immediately decides to chase after Sebastian, since “come what may, I adore thee so / That danger will seem 17 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai sport, and I will go” (2.1.). Antonio’s behaviour toward Sebastian seems to echo Orsino’s melodramatic love for Olivia, and Olivia’s exaggerated passion for Cesario. Like these other characters, Antonio is convinced he cannot live without one particular person, even though Sebastian seems to view him simply as a good friend. Antonio’s emotions echo the theme of unrequited love, and the unpredictable nature of passion and desire. Antonio is the one character who is authentically experiencing intense feelings for someone of the same sex. While everyone else eventually finds their way to an appropriate match, Antonio seems doomed to have his feelings unrequited and unresolved. Like Orsino, Antonio’s strong attachment to Sebastian leaves him vulnerable when he thinks he has been betrayed, lamenting that Sebastian’s “false cunning… Taught him to face me out of his acquaintance” (5.1.). Antonio eventually ends up receiving confirmation of Sebastian’s affection for him. However, Antonio is also conspicuously left alone at the end of the play, when almost everyone pairs off. He drops out of the main action without any clear resolution or statement as to what his fate will be. Despite having showed loyalty, courage, and love, Antonio’s virtues don’t seem to be rewarded at the end of the play. Miscellaneous Feste and the Significance of Songs What Symbolic Songs does Feste sing? O Mistress Mine Come Away Come Away Death The Wind and the Rain Feste often sings about universal subject matters. His nuanced songs address the human condition, and the pains of youth, love, death and time. They often provide much insight into the behaviour of love and lovers, especially when poking fun at the lovers around him. Act 2.3: The song “O mistress mine” bears the spirit of carpe-diem (seize the day) and reminds us of the ceaselessness of time or the inevitable passing of Time. Although no-one knows what is to come of the future, nothing, (including true love) will ever come from delay. Olivia & Viola’s youth will “not endure” the test of time. Folly of men and women to delay their love affairs. Act 2.4: In “Come Away Come Away Death”, Feste sings amidst (and about) selfabsorbed & delusional lovers. The song is a sly dig/ gibe at the lovers’ self- obsessed behaviour. It is a song of unrequited love; of the speaker who dramatically dies of spurned love. There lives derision and mockery of Orsino’s absurd inability to accept his beloved’s (Olivia’s) rejection in the song. Orsino is also made out to be a foolish, delusional lover who, like the speaker in the song, loved hopelessly until death. The effects of unrequited love create a sense of inertia and stasis in lovers who indulge in excessive self-indulgence. Their inability to come to terms with reality and rejection in love leaves them in a sterile and stale state; not being able to move 18 Zachary Matthew Khoo Wen Kai forward, which leads to a: Unattractive/Pessimistic/Negative Portrayal of Lovers who suffer the effects of unrequited love and waste away their lives Thus, Feste has a cursory purpose to entertain the nobility and his masters through witty dialogue & song. However, he is also, to an extent, a harbinger of truth, who provides much wisdom to budding relationships in the play and whose predictions turn out accurately. This links to the next minor subtheme: Feste: The Wise Fool *Read the KPA Sample Essays for specific examples of his witty quips, erudite showcases and foresight. It just came out and very likely will not come out again. **Feste’s name comes from the word “festival”, which goes right along with his occupation of being a clown. Feste is the source of most of the social commentary and satire in the play. He constantly tries to point out the foolishness and hilarity of what others are doing. He points out that it is stupid for Olivia to mourn her brother if he is in heaven and he played a performance about a lover dying when Orsino asked for a silly song about love. It is also ironic how Feste, the character who is supposed to be the fool in their society, is the one who understands the most of what is going on throughout the play. 19