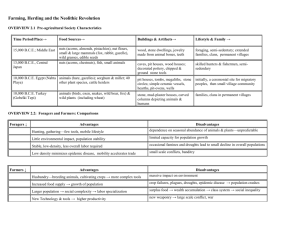

Emerging Markets Finance and Trade ISSN: 1540-496X (Print) 1558-0938 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/mree20 Effects of Transparency on Herding Behavior: Evidence from the Taiwanese Stock Market Kuei-Yuan Wang & Yu-Sin Huang To cite this article: Kuei-Yuan Wang & Yu-Sin Huang (2018): Effects of Transparency on Herding Behavior: Evidence from the Taiwanese Stock Market, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, DOI: 10.1080/1540496X.2018.1504289 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1504289 Published online: 26 Sep 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 5 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=mree20 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, 1–20, 2018 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1540-496X print/1558-0938 online DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1504289 Effects of Transparency on Herding Behavior: Evidence from the Taiwanese Stock Market Kuei-Yuan Wang1,2 and Yu-Sin Huang1 1 Department of Finance, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan; 2Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan ABSTRACT: This study combines the concepts of information asymmetry from classical finance theory and herding behavior from modern behavioral finance theory to investigate whether herding behavior exists in the Taiwan stock market. Scores from the Information Disclosure and Transparency Ranking System (IDTRs) are incorporated into the nonlinear model proposed by Chang, Cheng, and Khorana (2000). The empirical results reveal that herding behavior is prevalent in the Taiwan stock market and the implementation of the IDTRs has effectively discouraged such behavior. In addition, the empirical results of this study reveal that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. The empirical results confirm the government’s efforts to increase the transparency of listed firms in order to reduce information asymmetry and prevent investors from engaging in herding behaviors. KEY WORDS: herding behavior, Taiwanese stock market, transparency Since Christie and Huang (1995) proposed the cross-sectional standard deviation (CSSD) model as a method for examining investors’ herding behavior, numerous studies have reported the occurrence of herding behavior in stock markets in various countries (Chiang and Zheng 2010; Choe, Kho, and Stulz 1999; Hwang and Salmon 2004; Jlassi and Bensaïda 2014). Other studies have examined the causes of herding behavior in stock markets; for example, Chiang et al. (2013) reported a relationship between herding behavior and information asymmetry, whereas Ramli, Agoes, and Setyawan (2016) not only confirmed the effect of information asymmetry on herding behavior but also asserted that domestic investors follow foreign investors in making investment decisions because of the information asymmetry between domestic and foreign investors. However, few studies have examined the factors that discourage herding behavior. In addition, the evaluation results of Information Disclosure and Transparency Ranking System (IDTRs) are major applied in the corporate governance research (Hsu, Lai, and Li 2016; Lee and Lee 2015; Lee, Lee, and Wang 2017). This study combines the concepts of information asymmetry of classical finance theory and herding behavior of modern behavioral finance theory to investigate whether herding behavior exists in the Taiwan stock market, especially after introducing IDTRs by the financial supervisor institution, and becomes our first purpose. Although, Chung, Judge, and Li (2015) stated that the main objectives of information disclosure are to reduce information asymmetry and facilitate the accurate evaluation of firm value or potential. This study investigates the Taiwan stock market to verify whether increased information transparency can reduce information asymmetry, thereby discouraging herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market, and becomes our second purpose. There are three reasons for selecting the Taiwan stock market to explore. First, since the Taiwan government relaxed trading restrictions on foreign institutional investors in 2000, foreign investors have shown increasing interests in the Taiwan stock market. Second, Taiwan stock market is dominated by domestic individual investors as opposed to institutional and foreign investors (Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010). Demier, Kutan, and Chen (2010) asserted that most individual investors tend Address correspondence to Kuei-Yuan Wang, Department of Finance, Asia University, 500, Lioufeng Rd., Wufeng, Taichung 41354, Taiwan. E-mail: gueei5217@gmail.com Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/mree. 2 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG to lack professional knowledge and cannot access information accurately and easily. The resulting of information asymmetry may compel individual investors to follow the investment decisions of informed domestic and foreign institutional investors. Therefore, the Taiwan stock market is suitable for examining whether information asymmetry is a factor of herding behavior. Second, Taiwan Stock Exchange and Taipei Exchange commissioned the Securities and Futures Institute (SFI) executed the IDTRs in 2003. The main objectives of this system are to increase transparency among domestic firms, protect investors’ rights, facilitate the development of capital markets, and incentivize domestic firms to elevate their disclosure quality to international standards (Securities and Futures Institute 2013). Third, because Chung, Judge, and Li (2015) claimed that the IDTRs meets international standards. Therefore, this study considers that IDTRs have more public creditability. In summary, this study modified the nonlinear model proposed by Chang, Cheng, and Khorana (2000) and incorporated the evaluation results of IDTRs to our model to explore whether the implementation of the IDTRs effectively discouraged herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. This study also further investigates whether the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. The major contributions of this study are as follows: First, this study found that introducing IDTRs by the government could migrate investors’ herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. This empirical finding confirms the government’s efforts. Second, since introducing IDTRs might migrate investors’ herding behavior, this empirical findings might guide a direction to the government of the emerging markets while stabilizing their stock markets. Third, since this study found that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. It also provides some implications to the management of corporations while stabilizing their stock prices. Forth, similarly, since herding behaviors in the lower group of transparency are more prevalent than the one of higher group, this anomaly makes stock prices more unstable. The results of this study can be recommended to investors, allowing investors to make investment decisions according to their preferences. Fifth, prior literature mainly examined whether herding behavior exists, and its causes. This study further tries to explore how to migrate investors’ herding behaviors, and guides an interesting direction to the future research. Sixth, because IDTRs are implemented by the financial supervision institution, the evaluation results are closer to the real market than the data generated by the academic research models. Then, this study introduces the evaluation results into our analysis would let our empirical findings have more public credibility than some other literature that used the data from some folk research institutions or academic research models. The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Literature Review presents a literature review of herding behavior and the IDTRs, Methodology addresses the methodology of this study, Results discusses the empirical results, and Conclusions are the conclusions and recommendations. Literature Review Herding Behavior The earliest study of herding behavior in economics was The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by Keynes (1936). The book states that investors do not make decisions based solely on available information but rather observe other investors’ decision-making behaviors and follow suit. Herding behavior is a behavior that investors mimic other investors’ actions or market consensus to make their investment decisions rather than using information they owned (Banerjee 1992; Bikhchandani and Sharma 2000; Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010; Nofsinger and Sias 1999). Some herding behavior theories have been developed from information perspective. According to the information-related herding theory, informed investors’ behaviors are perceived as useful information by individual investors who lack information (Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010; Froot, Scharfstein, and Stein 1992; Shleifer and Summers 1990). The information cascade theory states that other individuals’ behaviors convey information to observant investors EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 3 who ignore their own information and follow others’ decisions, thereby triggering herding behavior (Banerjee 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirsheifer, and Welch 1992; Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010). Hsieh (2013) asserted that the causes of herding can generally be separated into two types: information-driven and behavior-driven. Information-driven herding may indicate that investors are facing similar decision-making problems and receiving related private information, whereas behaviordriven herding occurs when investors follow other investors’ actions. Zhou and Lai (2009) stated that a higher proportion of information-based trading increases the likelihood of herding by investors. Numerous studies have pointed out that individual investors have difficulty accessing sufficient information about small companies and behavior-driven herding affects small companies’ more than large companies (Hsieh 2013; Lakonishok, Vishny, and Vishny 1992; Shyu and Sun 2010; Sias 2004). According to Choi and Skiba (2015), some studies have asserted that herding is not driven by fundamental information and destabilizes stock prices, whereas other studies have argued that herding is driven by fundamental information and enables stock markets to be more efficient because stock prices adjust to new information quickly. In addition, Choi and Skiba (2015) emphasized that informationbased explanations for herding in financial markets include investigative herding and information cascades. Investigative herding occurs when investors react similarly to the correlated market signals, whereas information cascades occur when investors’ ignore private information in favor of making decisions by observing others. Non-information-based explanations for herding include reputationrelated reasons, characteristic herding, and fads. Because information regarding a stock’s fundamental value is of secondary concern to investors, non-information-based explanations are more likely to destabilize prices; for example, when managers of portfolios ignore private information and choose to mimic others’ investment decisions, they choose to follow the crowd even if doing so involves making wrong decisions, which results in reputational herding. However, Scharfstein and Stein (1990) asserted that although reputational herding is rational, the blame of wrong investment decisions is shared because such decisions are not made by a single manager. In addition, characteristic herding occurs when similar stock characteristics attract investors and investors might make similar investment decisions. Caparrelli, D’Arcangelis, and Cassuto (2004) found that herding behavior is prevalent in large and growing Italian firms, and it is migrated in bear markets. Hwang and Salmon (2004) found that herding reveals in both U.S. and South Korean stock markets no matter in the bear or bull markets. Tan et al. (2008) indicated that herding behavior appears in A shares in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges no matter in bull or bear markets. However, herding behavior is not prevalent in B shares of these two markets. But, Yao, Ma, and He (2014) obtained opposing findings that herding behavior in B shares in these two markets. Demier, Kutan, and Chen (2010) employed the nonlinear model proposed by Chang, Cheng, and Khorana (2000) (CCK model hereafter) and the state space model developed by Hwang and Salmon (2004) to measure herding behavior in various sectors of the Taiwan stock market. The empirical results revealed that herding is prevalent in most Taiwanese industries, especially during the bear markets. Hsieh (2013) reported the presence of institutional and individual herding in the Taiwan stock market and revealed that institutional herding is stronger than individual herding. Huang, Lin, and Yang (2015) reported an enhanced presence of herding in the Taiwan stock market during the 2007–2008 financial crisis. To sum up, herding behavior is a behavior that investors often mimic other investors’ decisions or market consensus while making their investment decisions rather than using their own information. And, herding behaviors exists in the Taiwan stock market. Information Disclosure and Transparency Ranking System (IDTRs) Taiwan Stock Exchange and GreTai Securities Market commissioned the SFI to carry out annual Information Transparency and Disclosure Ranking evaluation from 2003. The main goals of this rating are to improve transparency of firms, to protect the rights of investors, to develop the capital market, and to internationalize local companies, bringing them on track with international practices. The SFI’s annual rating consists of a complete set of corporate information that released by the company. The rating is conducted once a year and the results are reported in the following year. The rating includes companies that 4 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG have been traded on the stock market or over-the-counter for at least a year, excluding companies where the responsible party has known integrity issues or companies that are poorly managed (SFI 2013). Although the first year of the IDTR included only 62 indicators, there have been amendments and augmentations over the years. In the eighth and ninth ratings, there were 114 indicators, and in the eleventh evaluation, there were 109 indicators. The rating indicators can be divided into five main types, which are legal compliance (indicators 1–12), timeliness of disclosure (indicators 13–33), the disclosure of financial forecasts (indicators 34–37), the disclosure of annual report information (indicators 38–87), and information disclosure on the web (indicators 88–109) (Securities and Futures Institute 2013). In the first and second years of the evaluation, to encourage the IDTRS, only the top third of companies were publicized. In the third year, the companies were assigned into five grades: A+ (over 80), A (60–79), B (50–59), C (45–49), C− (under 45). Owing to the steady improvements, the results are assigned into seven grades: A++ (over 85), A+ (80–84), A (70–79), and A− (60–69), B (50–59), C (45–49), C− (under 45) (Securities and Futures Institute 2013). Lee and Lee (2015) used the evaluation results of IDTRs as a proxy for transparency to examine whether transparency could migrate the accruals anomaly. Hsu, Lai, and Li (2016) also took the evaluation results of IDTRs as a proxy of transparency to examine the influence of R&D intensity and institutional ownership on transparency in the high-tech, mid-tech, and traditional industries. The empirical findings show that transparency promotion and the increase of institutional ownership are statistically significantly related. Lee, Lee, and Wang (2017) took the empirical results of IDTRs as a proxy to information disclosure, and found that companies review by the industry-specialized chief accountant have higher grades of IDTRs than the ones that review by the non-industry-specialized chief accountant. Besides, the industry-specialized chief accountant could increase the credibility of firms’ transparency. According to the above literature, this study found that the evaluation results of IDTRs are major applied in the corporate governance research, and are often used to measure the transparency. Methodology Research Hypotheses Since the purposes of introducing IDTRs by the government is to promote the transparency of the whole stock market, and further to protect investors’ rights. In practice, from the evaluation results of IDTRs, we can found that the number of companies receiving an A Grade of transparency increased from 144 to 175 from 2005 to 2014. In addition, the number of companies receiving a C Grade decreased from 141 to 16. That is, samples are more and more transparency in the Taiwan stock market. Therefore, introducing the IDTRs by the government has effectively enhanced the information transparency in Taiwan stock market. Table 1. Summary of the evaluation results of the information disclosure and transparence ranking system (IDTRs) during 2005–2014. Year Rating A++ A+ A A− B C C− Total 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 – 11 144 – 334 141 – 630 – 12 171 – 326 106 20 635 – 11 167 – 308 131 34 651 – 29 222 – 362 48 4 665 – 28 222 – 332 94 9 685 – 34 241 – 324 96 10 705 15 19 111 173 314 83 5 720 20 32 132 197 292 75 6 754 39 42 115 204 273 86 14 773 60 48 175 289 208 16 1 797 Source: Securities and Futures Institute (2015). Data from: 2005–2014 Information disclosure and transparency ranking results in Taiwan [dataset]. Securities and Futures Institute Website. Accessed on 2nd May 2015. http://www.sfi.org.tw/cga/cga2. EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 5 Table 1 shows the evaluation results of the Information Disclosure and Transparency Ranking System (IDTRs) during 2005–2014. Data is from the website of Securities and Futures Institute. Chung, Judge, and Li (2015) proposed that increasing information transparency can reduce information asymmetry, whereas Choi and Skiba (2015) indicated that asymmetry causes information cascades.1 Therefore, increasing transparency can reducing information asymmetry, and further reducing information cascades. Since information cascades reduces, investors might not follow others’ investment decisions, and herding behavior might be discouraged. In summary, this study infers that the implementation of the IDTRs could enhance transparency and reduced information asymmetry. Consequently, investors do not need to follow others’ decisions like the lacking information anomaly before. Therefore, information cascade reduces, and herding behavior is migrated. Then, this study proposes the first hypothesis as follows: H1: Introducing IDTRs by the government could migrate the herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. If companies discloses less information, investors have less information to make investment decisions. From the information cascade views, observant investors might follow others’ decisions to make their investment decisions, then herding behavior is produced. Therefore, this study infers that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market, and proposes the second hypothesis as follows: H2: The lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. Sample Selection and Source This study takes the listed firms that joined the IDTRs as samples to explore. The number of samples of each group in each year show in the Table 2. Daily return data is from Taiwan Economic Database (TEJ), and transparency is adopted by the IDTRs results published by the SFI. This study defines the year of 1993–2002 as the period before the implementation of the IDTRs, and the year of 2005–2014 as the period after the implementation of the IDTRs. The reason that this study ignores the period of 2003–2004 is that seldom firms join this evaluation system owing to the promotion nature of this stage. Furthermore, this study denotes the evaluation results of IDTRs of A++, A+, A and A− as the group with higher transparency, and the ones of C and C− as the group with lower transparency. Then, this study further uses these groups to explore whether the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. Table 2 shows the number of samples in each sample year. Before represents 1993–2002 years that they are the periods before implementing IDTRs by the government, and After represents 2005–2014 years that they are the periods after implementing IDTRs by the government. High denotes the group with higher transparency, which evaluation grades are A++, A+, A and A−. Table 2. Number of samples in each year. Panel A: Information Disclosure and Transparence Ranking Before Year 1993 1994 1995 1996 N 203 225 267 307 After Year 2005 2006 2007 2008 N 630 635 651 665 Panel B: Transparency High Year 2005 2006 2007 2008 N 155 183 178 251 Low Year 2005 2006 2007 2008 N 141 126 165 52 System 1997 342 2009 685 1998 394 2010 705 1999 463 2011 720 2000 525 2012 754 2001 577 2013 773 2002 689 2014 797 2009 250 2009 103 2010 275 2010 106 2011 318 2011 88 2012 381 2012 81 2013 400 2013 100 2014 572 2014 17 6 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG Low denotes the group with lower transparency, which evaluation grades are C and C−. N represents the observations. Herding Tests Christie and Huang (1995) proposed that herding occurs when investors frequently abandon their own investment decisions in favor of following the collective actions of the market. Because most investors make similar investment decisions, individual returns do not stray far from the market return. Therefore, Christie and Huang (1995) developed the CSSD model (CH model hereafter), and indicated that herding behavior can be examined by exploring whether CSSD significantly small in the extreme large positive or negative return distributions. However, Chang, Cheng, and Khorana (2000) asserted that the CH model is too stringent. Rational asset pricing models predict not only that stock return dispersions are an increasing function of market return, but also that the relationship between the two is linear. However, if investors herd irrationally, the increasing linear relationship between dispersion and market return no longer holds. Demier, Kutan, and Chen (2010) proposed that using the linear CH model to measure herding may overlook the price comovement between the returns on individual assets and those of the market; for example, observing a drop in all asset prices along with the market portfolio on any given day causes the dispersion measure to take a lower value for that day to provide support for the existence of herding. However, this might be a result of a common reaction to unanticipated news on that day among investors, which a test would fail to detect. The linear CH model failing to determine the price comovement may lead to inaccurate results. By contrast, the nonlinear CCK model allows for nonlinear comovement between return dispersions and market returns while testing for the existence of herding by examining the additional nonlinear term in the model. Therefore, the nonlinear CCK model provides a more flexible and accurate approach to testing for herding formation than does the linear CH model. The CCK model is described as follows: CSAD ¼ Pn Ri;t Rm;t i¼1 n1 where, Ri;t represents the individual stock return rate; Rm;t represents the equal-weighted portfolio return rate; n represents the observations. CSADf ;t ¼ α þ β1;f Rm;t þ β2;f ðRm;t Þ2 þ εt (1) CSADh;t ¼ α þ β1;h Rm;t þ β2;h ðRm;t Þ2 þ εt (2) where, f = 1 denotes the period of 1993-2002 years before the implementation of the IDTRs; f = 0 denotes the period of 2005–2014 years after the implementation of the IDTRs; h = 1 denotes the group with higher transparency of grade A++,A+, A, A−; h = 0 denotes the group with lower transparency of grade C, C−; and the presence of statistically significantly negative β2,f (β2,h) indicates that herding behavior exists.2 To measure asymmetric investor behavior under various market conditions, Chiang and Zheng (2010) modified the CCK model by adding Rm,t to the right-hand side. In addition, Yao, Ma, and He (2014) added a 1-day lag of cross-sectional absolute deviation of returns (CSAD) on the right-hand side of the CCK model to improve its explanatory power. Therefore, this study adopts these two approaches to modify the CCK model as follows: (3) CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γ1;f Rm;t þ γ2;f Rm;t þ γ3;f ðRm;t Þ2 þ γ4;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR CSADh;t ¼ α þ γ1;h Rm;t þ γ2;h Rm;t þ γ3;h ðRm;t Þ2 þ γ4;h CSADh;t1 þ εt 7 (4) Subsequently, this study employs the CCK model, modified CCK model, and Chow test to test H1 and H2. Sensitivity Analysis To test whether H1 and H2 are supported in up or down markets, this study defines when Rm,t > 0 represents the up market, and when Rm,t < 0 represents the down market. Besides, this study adopts the dummy variable approach in Chiang and Zheng (2010) and incorporates the perspective of Yao, Ma, and He (2014) to modify the CCK model. The CCK model further modified in this study is expressed as follows: up 2 down CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γup 1;f DRm;t þ γ2;f DðRm;t Þ þ γ3;f ð1 DÞRm;t 2 þ γdown 4;f ð1 DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ5;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt up 2 2 down down CSADh;t ¼ α þ γup 1;h DRm;t þ γ2;h DðRm;t Þ þ þγ3;h ð1 DÞRm;t þ γ4;h ð1 DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ5;h CSADh;t1 þ εt (5) (6) where, DRup is that D times Rup. D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents the up market (Rm;t > 0); up down down D = 0 represents the down market (Rm;t < 0); If γup 2;f (γ4;f ) and γ2;h (γ4;h ) are significantly negative, then they represent that herding behavior exist in the up (down) market. Numerous studies have reported that herding is more prevalent than usual during a financial crisis (Economou, Katsikas, and Vickers 2016; Huang, Lin, and Yang 2015; Jlassi and Bensaïda 2014). Since the Asian financial crisis and subprime mortgage crisis exist in our sample period, this study refers to Kaminsky and Schmukler (1999) and Erkens, Hung, and Matos (2012) to define the Asian financial crisis as the period of 1997–1998, and subprime mortgage crisis as the period of 2007–2008, and the others defines as the normal market period. This study follows the modified CCK model mentioned by Chiang and Zheng (2010) to examine whether the hypothesis 1 and 2 can be supported under normal market and financial crisis conditions, the modified equations are as follows. CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γ1;f DRm;t þ γ2;f DRm;t þ γ3;f DðRm;t Þ2 þ γcrisis 4;f ð1-DÞRm;t 2 crisis þ γcrisis 5;f ð1-DÞRm;t þ γ6;f ð1-DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ7;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt (7) crisis CSADh;t ¼ α þ γ1;h DRm;t þ γ2;h DRm;t þ γ3;h DðRm;t Þ2 þ γcrisis 4;h ð1-DÞRm;t þ γ5;h ð1-DÞRm;t 2 þ γcrisis 6;h ð1-DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ7;h CSADh;t1 þ εt (8) where, D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents the normal market; D = 0 represents the financial crisis crisis period; If γ3;f (γcrisis 6;f ) and γ3;h (γ6;h ) are significantly negative, then they represent that herding behavior exist in the normal market (financial crisis). Christie and Huang (1995) indicated that herding behavior are easier to appear in the extreme market. This study took the 10% upper and lower tails of the trading volume as the criteria of the extreme market movements, and utilized Equations 3 and 4 to examine whether the hypothesis 1 and 2 can be supported under the extreme market conditions. 8 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG 65 Grade 60 55 50 45 2005 2006 2007 2008 Year 2009 2010 2011 2012 Figure 1. The average scores of IDTRs in Taiwan during 2005–2012. Source: Securities and Futures Institute (2013). Results Descriptive Statistics The main objective of the IDTRs is to increase the transparency of companies and serve as a reference for investor’ decisions and rights. Figure 1 illustrates the annual mean IDTRs scores between 2005 and 2012 and demonstrates that the mean score increased annually between 2005 and 2012. Therefore, the implementation of the IDTRs has effectively increased transparency among Taiwanese companies, thereby reducing information asymmetry. Table 3 demonstrates that the average CSAD scores before and after the implementation of the IDTRs are 0.0166 and 0.0142, respectively, and the average CSAD scores for the low and high transparency groups are 0.0146 and 0.0135, respectively. The minimum CSADs of all four variables are positive and approach zero. The observations of Rm indicates that the maximum and minimum of any Rm fall within the range of (−0.0644, 0.0635), which correlates with the maximum quota change of 7% regulated by the Taiwan Securities and Exchange Act. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistic of the daily CSAD and the equal-weighted portfolio return rate (Rm). Mean represents the average of CSAD or Rm. Std. represents the standard Table 3. Descriptive statistic. Information disclosure and transparence ranking system CSAD Rm Mean Std. Min Max N ADF Mean Std. Min Max N ADF Transparency Before After Low High 0.0166 0.0053 0.0055 0.0393 2,735 (−10.10)*** 0.0004 0.0148 −0.0644 0.0602 2,735 (−45.47)*** 0.0142 0.0039 0.0066 0.0351 2,483 (−6.37)*** 0.0005 0.0127 −0.0622 0.0629 2,483 (−43.12)*** 0.0146 0.0045 0.0042 0.0364 2,483 (−6.20)*** 0.0006 0.0125 −0.0608 0.0620 2,483 (−41.76)*** 0.0135 0.0038 0.0053 0.0359 2,483 (−6.39)*** 0.0005 0.0127 −0.0630 0.0635 2,483 (−44.37)*** Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 9 deviation. Min and Max represents the minimum and maximum. N represents the observations. T-values of ADF tests show in the parentheses, ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively; Before represents the period of 1993–2002 that is before the IDTRs implementation. After represents the period of 2005–2014 that is after the IDTRs implementation. Low represents the relatively lower transparency group with the evaluation grades of C and C−. High represents the relatively higher transparency group with the evaluation grades of A++, A+, A and A−. Effects of the IDTRs on Herding Behavior Table 4 shows that in Panel A, the γ3,Before and γ3,After coefficients in the modified CCK model are −5.3830 and −4.8402, respectively. Both coefficients reach the statistically significant level, indicating the presence of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market before and after the implementation of the IDTRs. This study uses the Chow test to confirm that γ3,After exceeds γ3,Before by 0.5428, which is a significant difference. Therefore, the implementation of the IDTRs effectively discourages investors from engaging herding behavior. In Panel B, the β2,Before and β2,After coefficients are significantly negative in the CCK model, indicating a significant level of herding behavior before and after the implementation of the IDTRs. In addition, the Chow test results reveal that β2,After is significantly larger than β2,Before, thereby indicating a reduction in herding behavior between 1993–2002 and 2005–2014. The consistency of the empirical results between Panels A and B demonstrates that the implementation of the IDTRs effectively discouraged investors’ herding behaviors. Therefore, H1 is supported. Table 4 shows the comparison effects of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. Panel A shows the empirical results of Equation 3, and Panel B shows the empirical results of Equation 1. 3 is as follows: Equation 2 CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γ1;f Rm;t þ γ2;f Rm;t þ γ3;f ðRm;t Þ þ γ4;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt , and Equation 1 is as follows: CSADf ;t ¼ α þ β1;f Rm;t þ β2;f ðRm;t Þ2 þ εt . CSAD denotes the CSAD. f = 1 represents the period that before the IDTRs implementation; otherwise, f = 0 represents the one after it. Rm;t represents the equalweighted portfolio return rate on t day. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square Table 4. The effects of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. Panel A: Modified CCK Model Α γ1,Before 0.0020 −0.0040 (10.55)*** (−1.05) Α γ1,After 0.0031 −0.0295 (17.26)*** (−7.90)*** Chow test Panel B: CCK Model Α β1,Before 0.0133 0.4406 (74.83)*** (18.35)*** Α β1,After 0.0116 0.4046 (98.73)*** (22.63)*** Chow test γ2,Before γ3,Before 0.2973 −5.3830 (20.39)*** (−15.49)*** γ2,After γ3,After 0.2866 −4.8402 (22.99)*** (−16.32)*** γ3,After - γ3,Before γ4,Before adj-R2 0.7544 0.6988 (69.61)*** γ4,After adj-R2 0.6646 0.6647 (53.28)*** [15.31]*** β2,Before −6.6128 (−11.46)*** β2,After −5.1847 (−12.17)*** β2,After - β2,Before Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. N 2735 N 2483 0.5428 adj-R2 0.1645 N 2735 adj-R2 0.2808 N 2483 [83.52]*** 1.4281 10 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG Table 5. The effects of transparency on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. Panel A: Modified CCK Model α γ1,Low 0.0035 −0.0132 (18.00)*** (−2.78)*** α γ1,High 0.0033 −0.0238 (18.24)*** (−6.20)*** Panel B: CCK Model Chow test α β1,Low 0.0113 0.5025 (83.96)*** (24.21)*** α β1,High 0.0110 0.3748 (94.72)*** (21.22)*** Chow test γ2,Low 0.3603 (23.01)*** γ2,High 0.2741 (21.17)*** γ3,Low −5.7809 (−14.96)*** γ3,High −4.3434 (−14.21)*** γ3,Low - γ3,High β2,Low −6.6623 (−13.02)*** β2,High −4.4733 (−10.69)*** β2,Low - β2,High γ4,Low 0.6073 (45.96)*** γ4,High 0.6315 (47.75)*** adj-R2 0.6244 N 2483 adj-R2 0.6211 N 2483 adj-R2 0.3038 −1.4375 N 2483 adj-R2 0.2725 N 2483 [11.12]*** [48.97]*** −2.1890 Note: ***,**,* represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Effects of Transparency on Herding Behavior Table 5 shows that in Panel A, the γ3,Low and γ3,High coefficients in the modified CCK model are −5.7809 and −4.3434, respectively. Both coefficients exhibit statistical significance, indicating a strong presence of herding behavior in both transparency groups. This study uses the Chow test to confirm that γ3,Low exceeds γ3,High by −1.4375, which is a significant difference. Therefore, the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market, and increasing transparency effectively prevents investors from engaging in herding behavior. In Panel B, the β2,Low and β2,High coefficients are significantly negative in the CCK model, indicating that herding behaviors exist in both transparency groups. The Chow test results reveal that β2,Low is significantly less than β2,High, thereby indicating that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. That is, increasing transparency discourages investors’ herding behaviors. Therefore, H2 is supported. Table 5 shows the effects of transparency on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. Panel A shows the empirical results of Equation 4, and Panel B shows the ones of Equation 2. Equation 4 is as follows: CSADh;t ¼ α þ γ1;h Rm;t þ γ2;h Rm;t þ γ3;h ðRm;t Þ2 þ γ4;h CSADh;t1 þ εt , and Equation 2 is as follows: CSADh;t ¼ α þ β1;h Rm;t þ β2;h ðRm;t Þ2 þ εt . CSAD denotes the CSAD. h = 1 represents the group of higher transparency; otherwise, h = 0 represents the one of lower transparency. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Herding Behavior in Up and Down Markets Table 6 shows investors’ herding behaviors in up and down markets in Taiwan before (1993–2002) and after (2005–2014) the implementation of the IDTRs. The γup2,Before, γdown4,Before, γup2,After, and EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 11 Table 6. The effects of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors in the upper and down zone in the Taiwan stock market. α 0.0020 (10.51)*** α 0.0031 (17.11)*** Chow test γup1,Before 0.3318 (19.79)*** γup1,After 0.2744 (19.02)*** γup2,Before −6.7508 (−15.21)*** γup2,After −5.5251 (−13.87)*** [13.69]*** Chi-square γdown3,Before γdown4,Before γ5,Before −0.2647 −4.1337 0.7549 (−15.68)*** (−9.63)*** (69.95)*** γdown3,After γdown4,After γ5,After −0.2995 −4.3181 0.6655 (−20.34)*** (−12.02)*** (53.39)*** γup2,After - γup2,Before 1.2256 γup2,Before - γdown4,Before 2.6171 [24.20]*** adj-R2 0.7013 N 2735 adj-R2 0.6655 N 2483 γdown4,After - γdown4,Before −0.1844 γup2,After - γdown4,After 1.2070 [6.62]*** Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. γdown4,After coefficients are all significantly negative. Table 6 reveals a significant presence of herding behavior in up and down markets before and after the implementation of the IDTRs. The Chow test results that γup2,After exceeds γup2,Before by 1.2256, which is a significant difference. Therefore, the implementation of the IDTRs can discourage herding behavior in up markets. Although a significant difference between γdown4,After and γdown4,Before was revealed, γdown4,After being lower than γdown4,Before by −0.1844, and reveals that the implementation of the IDTRs failed to discourage herding behavior in down markets. The chi-square test results in Table 6 verify whether asymmetry existed between investors’ herding behaviors in up and down markets in Taiwan before and after the implementation of the IDTRs. The test results reveal a significant difference between γup2,Before and γdown4,Before, by 2.6171, indicating the occurrence of asymmetrical herding behaviors in up and down markets before the implementation of the IDTRs. Similarly, a significant difference between γup2,After and γdown4,After by 1.2070 is observed, indicating the occurrence of asymmetrical herding behaviors in up and down markets after the implementation of the IDTRs. Table 6 shows the empirical results of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors in up and down markets in the Taiwan stock market. Before represents the period of 1993–2002 before implementing IDTRs, and after represents the period of 2005–2014 years after it. Equation 5 is utilized, and shows as follows: up 2 2 down down CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γup 1;f DRm; t þ γ2;f DðRm;t Þ þ γ3;f ð1 DÞRm;t þ γ4;f ð1 DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ5;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt : CSAD denotes the CSAD. f = 1 represents the period that is before the IDTRs implementation; otherwise, f = 0 represents the one after it. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents Rm;t > 0 on t day; otherwise, D = 0 represented Rm;t < 0 on t day. T-value shows in the Table 7. The effects of transparency on herding behaviors in the up and down markets in the Taiwanese stock market. α 0.0110 (29.64)*** α 0.0104 (31.33)*** Chow test Chi-square γup1,Low γup2,Low 0.5539 −8.0128 (19.96)*** (−10.44)*** γup2,High γup1,High 0.3964 −5.2041 (17.51)*** (−9.08)*** [25.17]*** γdown3,Low γdown4,Low −0.4610 −5.5636 (−18.43)*** (−8.92)*** γdown3,High γdown4,High −0.3783 −4.2961 (−17.54)*** (−8.10)*** γup2,Low - γup2,High −2.8087 γup2,Low - γdown4,Low −2.4492 [7.96]*** Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. γ5,Low 0.0170 (0.85) γ5,High 0.0349 (1.77)* adj-R2 0.3061 N 2483 adj-R2 0.2733 N 2483 γdown4,Low - γdown4,High −1.2675 γup2,High - γdown4,High −0.9080 [1.79] 12 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Table 7 shows investors’ herding behaviors in up and down markets and in both transparency groups. The γup2,Low, γdown4,Low, γup2,High, and γdown4,High coefficients are all significantly negative. Table 7 demonstrates a significant presence of herding behavior under all four conditions. The Chow test results reveal that γup2,Low is significantly smaller than γup2,High by −2.8087, which indicates that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. That is, increasing transparency can discourage investors from engaging in herding behavior in up markets. Similarly, γdown4,Low is significantly smaller thanγdown4,High by −1.2675, which also indicates that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. That is, increasing transparency can discourage investors from engaging in herding behavior in down markets. In addition, the chisquare results demonstrate that in the low transparency group, herding behaviors in up and down markets exhibit asymmetry. However, herding behaviors in up and down markets in the high transparency group do not exhibit significant asymmetry, since the empirical results do not reach the significant level. Table 7 shows the effects of transparency on herding behaviors in up and down markets and in both higher and lower transparency groups. Equation 6 is utilized, and shows as follows: CSADh;t ¼ α þ up 2 2 down down γup 1;h DRm;t þ γ2;h DðRm;t Þ þ γ3;h ð1 DÞRm;t þ γ4;h ð1 DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ5;h CSADh;t1 þ εt CSAD denotes the CSAD. h = 1 represents the group of higher transparency; otherwise, h = 0 represents the one of lower transparency. Rm;t denots the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents Rm;t > 0 on t day; otherwise, D = 0 represents Rm;t < 0 on t day. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Table 8 shows the empirical results of herding behaviors under normal market conditions and during financial crises before (1993–2002) and after (2005–2014) the implementation of the IDTRs. The γ3,Before, γcrisis6,Before, γ3,After, and γcrisis6,After coefficients are significantly negative, and reveal that herding behaviors exist under all four conditions. The Chow test results reveal that γ3,After exceeds γ3, crisis crisis Before by 1.8158, but γ 6,After is smaller than γ 6,Before by −1.8465. These results reveal that the implementation of the IDTRs discouraged investors’ herding behavior under normal market conditions, but herding behavior increases during financial crises. The chi-square test between γ3,Before and γcrisis6,Before demonstrates that herding behaviors in the normal market or financial crisis are not significantly different before (1993–2002) the implementation of the IDTRs. However, the chi-square test between γ3,After and γcrisis6,After are significantly different by 2.9257, which indicates that after the implementation of the IDTRs, herding behavior during financial crises is more severe than that under normal market conditions after the implementation of the IDTRs. Based on the financial intuition, in theory, investors should have the similar attitudes toward the different financial crises, but the two chi-square tests reveal that financial crises exert varying effects on investors’ herding behaviors. This study refers to Kaminsky and Schmukler (1999) that, relative to other Asian stock markets, Investors in the Taiwan stock market were not heavily directly damaged during the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis. But, 2008 subprime mortgage crisis affected worldwide investors including Taiwan stock market. This is the reason why herding behaviors in the normal condition before the implementation of the IDTRs are more severe than those during the financial crisis. Table 8 shows the empirical results of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors under normal market and in the financial crisis in the Taiwan stock market. Before represents the period of 1993–2002 before implementing IDTRs, and after represents the period of 2005–2014 years after it. Equation 7 is utilized, and shows as follows: CSADf ;t ¼ α þ EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 13 Table 8. The effects of IDTRs implementation and financial crises on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. α 0.0020 (10.51) *** α 0.0035 (18.57) *** Chow test Chi-square γ1,Before −0.0013 (−0.32) *** γ1,After −0.0307 (−6.30) *** γ2,Before γ3,Before 0.2990 −5.4733 (19.90) (−15.16) *** *** γ2,After γ3,After 0.2455 −3.6575 (17.30) (−9.22)*** *** [13.70]*** γcrisis4, γcrisis5, Before Before −0.0151 (−1.68)* 0.2814 (11.61) *** γcrisis6,Before γ7,Before adj-R2 N −4.7367 (−6.15)*** 0.7553 0.6988 2735 (69.59) *** γcrisis4,After γcrisis5,After γcrisis6,After γ7,After adj-R2 N −0.0217 0.3631 −6.5832 0.6395 0.6708 2483 (−3.80) (21.46) (−16.55) (49.06) *** *** *** *** γcrisis6,After - γcrisis6,Before γ3,After - γ3,Before 1.8158 −1.8465 γ3,After - γcrisis6,After γ3,Before - γcrisis6,Before −0.7366 [0.90] 2.9257 [32.87]*** Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. crisis γ1;f DRm;t þ γ2;f DRm;t þ γ3;f DðRm;t Þ2 þ γcrisis ð1 DÞR þ γ ð1 DÞ R m;t m;t þ 4;f 5;f 2 γcrisis 6;f ð1DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ7;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt CSAD denotes the CSAD. f = 1 represents the period that before the IDTRs implementation; otherwise, f = 0 represents the one after it. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents during the normal market; otherwise, d = 0 represents in the financial crisis. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Table 9 shows herding behaviors under normal market conditions and during financial crises in the two transparency groups. The γ3,Low, γcrisis6,Low, γ3,High, and γcrisis6,High coefficients are all significantly negative. Table 9 demonstrates a significant presence of herding behavior under all four conditions. The Chow test results reveal that γ3,Low is significantly smaller than γ3,High by −1.5867, and γcrisis6,Low is significantly smaller than γcrisis6,High by −1.2781. Therefore, the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. That is, elevating transparency can discourage investors from engaging in herding behavior under both normal market and financial crisis conditions. The chi-square test results reveal that regardless of transparency group, herding behavior is more apparent during financial crises than under normal market conditions. From the financial intuition point of view, in general, investors intuitively regard the financial crisis as bad news, then the herding behaviors might be more severe during the financial crisis than in the normal market. Table 9 shows the empirical results of herding behaviors under normal market and in the financial crisis in the higher and lower transparency groups. Equation 8 is utilized, and shows as 2 crisis ¼ α þ γ DR þ γ D R follows: CSAD 1;h 2;h h;t m;t m;t þ γ3;h DðRm;t Þ þ γ4;h ð1 DÞRm;t þ 2 γcrisis Rm;t þ γcrisis 5;h ð1 DÞ 6;h ð1DÞðRm;t Þ þ γ7;h CSADh;t1 þ εt CSAD denotes the CSAD. h = 1 repre- sents the group of higher transparency; otherwise, h = 0 represents the one of lower transparency. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. D is a dummy variable. D = 1 represents during the normal market; otherwise, d = 0 represents in the financial crisis. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. γ1,Low −0.0049 (−0.78) γ1,High −0.0261 (−5.22)*** γ2,Low γ3,Low 0.3159 −4.5156 (17.78)*** (−8.84)*** γ2,High γ3,High 0.2234 −2.9289 (15.12)*** (−7.11)*** [8.29]*** γ3,Low - γcrisis6,Low 3.2159 [23.31]*** γcrisis4,Low −0.0197 (−2.74)*** γcrisis4,High −0.0135 (−2.31)** Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. Chi-square Α 0.0039 (18.97)*** Α 0.0038 (20.06)*** Chow test γcrisis5,Low 0.4416 (20.89)*** γcrisis5,High 0.3699 (21.14)*** γ3,Low - γ3,High −1.5867 γcrisis6,Low −7.7315 (−14.75)*** γcrisis6,High −6.4534 (−15.93)*** Table 9. The effects of transparency and financial crisis on herding behaviors in the Taiwan stock market. γ7,Low adj-R2 0.5858 0.6289 (42.67)*** γ7,High adj-R2 0.5973 0.6311 (43.17)*** γcrisis6,Low - γcrisis6,High −1.2781 γ3,High - γcrisis6,High 3.5245 [45.19]*** N 2483 N 2483 14 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG (−0.57) (8.31)*** α (−0.30) (10.15)*** (8.17)*** γ6,Before 0.2032 γ5,Before −0.0023 0.0038 (5.68)*** γ2,Before 0.3118 γ1,Before −0.0089 α 0.0095 γ3,Before (−2.00)** −1.2541 γ7,Before (−5.99)*** −7.5872 γ4,Before (13.19)*** 0.4572 γ8,Before (9.67)*** 0.4996 N 276 N 276 adj-R2 0.6756 adj-R2 0.3341 Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. 10% lower trail 10% upper tail (6.54)*** 0.0035 α (7.84)*** 0.0067 α (−1.09) −0.017901 γ5,After (−1.39) −0.0194 γ1,After (0.97) 0.0517 γ6,After (5.20)*** 0.2525 γ2,After (1.25) 1.6128 γ7,After (−4.33)*** −4.6420 γ3,After (17.44)*** 0.6578 γ8,After (12.14)*** 0.5516 γ4,After 248 N 248 N 0.6582 adj-R2 0.4452 adj-R2 [10.55]*** Chow test [8.69]*** Chow test 2.8669 γ7,After - γ7,Before 2.9452 γ3,After - γ3,Before Table 10. The effects of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors while the trading volume following in the extreme market movements in the Taiwan stock market. EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 15 16 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG Herding Behavior During Extreme Market Movements In Table 10, this study explores, while the trading volume following in the extreme 10% upper and lower tails, whether herding behaviors exist. In addition, each subsamples are further divided into two periods of before (1993–2002) and after (2005–2014) the implementation of the IDTRs. In Table 10, the coefficients of γ3,After, γ3,Before and γ7,Before are all statistically significant negative. These results show that, before implementing the IDTRs, when the trading volume are in both 10% upper and lower tails, investors show herding behaviors. But, after implementing the IDTRs, when the trading volume are in the 10% upper tail, investors show herding behaviors. However, in the 10% lower tail, investors do not show herding behaviors. Furthermore, from the financial intuition viewpoint, this study suggests that when the trading volume is larger, the stock market fluctuates more. And, when the markets are in the extreme fluctuation, investors, especially those who lack information, are easier to follow the market or others to make investment decisions. Therefore, herding behaviors are more prone to produce. The phenomenon when the trading volume are in the extreme 10% tails before the implementation of the IDTRs, investors show herding behaviors is consistent with the financial intuition viewpoint. However, in the 10% lower tail after the implementation of IDTRs, the findings do not support the financial intuition viewpoint. Kaminsky and Schmukler (1999) has indicated that Taiwan stock market was soaring in 1990s, and implied that investors have consistent opinions in that period. Maybe this is why, in the 10% lower tail, investors still have herding behaviors before the implementation of the IDTRs. The Chow test results reveal that γ3,After is significantly larger than γ3,Before, which indicates that the implementation of the IDTRs effectively discouraged herding behavior in the 10% upper tail. Similarly, γ7,After is significantly larger than γ7,Before, which indicates that the implementation of the IDTRs effectively discouraged herding behavior in the bottom 10% tail. Therefore, H1 is supported. This study took the 10% upper and lower tails of the trading volume as the criteria of the extreme market movements. Table 10 shows the empirical results of IDTRs implementation on herding behaviors while the trading volume following in the extreme 10% upper and lower tails. Before represents the period of 1993–2002 before implementing IDTRs, and after represents the period of 2005–2014 years after it. Equation 3 is utilized, and shows as follows: CSADf ;t ¼ α þ γ1;f Rm;t þ γ2;f Rm;t þ γ3;f ðRm;t Þ2 þ γ4;f CSADf ;t1 þ εt . CSAD denotes the CSAD. f = 1 represents the period that before the IDTRs implementation; otherwise, f = 0 represents the one after it. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Table 11 shows the herding behaviors in the 10% lower and upper tails in both transparency groups. γ3,Low and γ3,High are significantly negative, which indicates a significant presence of herding behavior in the 10% upper tail in both transparency groups. γ7,Low is not significant, whereas γ7,High is significantly positive. Therefore, herding behavior is not prevalent in the 10% lower tail in either high or low transparency group. The above finding is in line with financial intuition. In general, the larger the trading volume of the market, the more prone to heavy fluctuations. When the market is in the heavy fluctuations, investors are prone to follow others to make decisions, and herding behaviors produce. The Chow test between γ3,Low and γ3,High reveals that the lower level of transparency, the more prevalent of herding behavior in the Taiwan stock market. That is, increasing transparency can effectively discourage herding behavior in the 10% upper tail, thereby supporting H2. However, the Chow test between γ7,Low and γ7,High reveals no significant differences between the two variables. Therefore, increasing transparency does not affect herding behavior in the 10% lower tail, and thus H2 is not supported. This study took the 10% upper and lower tails of the trading volume as the criteria of the extreme market movements. Table 11 shows empirical results of the herding behaviors while the trading volume (−1.75)* (6.21)*** (2.35)** γ6,Low 0.1427 γ5,Low (6.37)*** −0.0355 α γ2,Low 0.3450 0.0037 (0.68) (6.82)*** γ1,Low 0.0101 α 0.0058 (−0.28) −0.4397 γ7,Low (−4.66)*** (15.19)*** 0.6290 γ8,Low (13.31)*** γ4,Low 0.5615 γ3,Low −5.5059 N 248 N 248 adj-R2 0.6133 adj-R2 0.5219 Note: ***, **, * represents the significant level of 1%, 5%, 10%, respectively. 10% lower trail 10% upper tail (6.51)*** 0.0034 α (8.69)*** 0.0074 α (−0.84) −0.0136 γ5,High (−1.14) −0.0159 γ1,High (0.38) 0.0210 γ6,High (4.11)*** 0.2151 γ2,High (1.85)* 2.4037 γ7,High (−3.16)*** −3.7190 γ3,High (17.32)*** 0.6589 γ8,High (10.61)*** 0.5038 γ4,High 248 N 248 N 0.6540 adj-R2 0.3788 adj-R2 [1.18] Chow test [2.36]** Chow test −2.8434 γ7,Low - γ7,High −1.7869 γ3,Low - γ3,High Table 11. The effects of transparency on herding behaviors while the trading volume following in the extreme market movements in the Taiwan stock market. EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 17 18 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG following in the extreme 10% upper and lower tails in both higher and lower transparency groups. Equation 4 is as follows: CSADh;t ¼ α þ γ1;h Rm;t þ γ2;h Rm;t þ γ3;h ðRm;t Þ2 þ γ4;h CSADh;t1 þ εt . CSAD denotes the CSAD. h = 1 represents the group of higher transparency; otherwise, h = 0 represents the one of lower transparency. Rm;t denotes the equal-weighted portfolio return rate on t day. T-value shows in the parentheses, and F-value shows in the square brackets. ***, **, * represents the significant level that reaches the 1%, 5% or 10%, respectively. N represents the observations. Conclusions This study combines the concepts of information asymmetry from classic finance theory and herding behavior from modern behavioral finance theory to investigate whether herding behavior exists in the Taiwan stock market. The empirical period is divided into the following two time periods: before (1993–2002) and after (2005–2014) the implementation of the IDTRs. The empirical results reveal that herding behavior has been ubiquitous in the Taiwan stock market before and after the implementation of the IDTRs. The Chow test results demonstrate that the implementation of the IDTRs strongly discouraged herding behavior in Taiwan, thereby supporting H1. This study investigates listed stocks between 2005 and 2014 and divides the samples into high and low transparency according to the annual IDTRs report published by the SFI. The results reveal the presence of herding behavior regardless of transparency group. Subsequently, this study uses the Chow test to verify whether a significant difference exists between the herding behaviors of these two groups. The empirical results reveal that herding behavior has a stronger presence in the low transparency group than in the high transparency group, thereby supporting H2. Maybe information cascade theory could explain for the empirical findings. According to the information cascade theory, investors abandon the information they possess and follow others’ decisions, thereby producing herding behaviors (Banerjee 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirsheifer, and Welch 1992; Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010). Choi and Skiba (2015) indicated that information asymmetry causes information cascades. Hence, reducing information asymmetry can prevent information cascades, thereby reducing herding behavior. Besides, Chung, Judge, and Li (2015) emphasized that increasing transparency can reduce information asymmetry. Based on the above, this study infers that increasing transparency can discourage investors’ herding behavior. This result is echoed by the empirical results of this study, and H1 and H2 are supported. The empirical results show that herding behavior universal exists in the Taiwan stock market, and is consistent with the ones of Chang, Cheng, and Khorana (2000), Demier, Kutan, and Chen (2010), Chiang and Zheng (2010). Moreover, this study finds that the herding behavior of investors are more severe during the financial crisis period of 2007–2008 than the normal periods. However, this study does not find that herding behavior of investors are more severe during the Asia financial crisis of 1997–1998 than the normal periods. This empirical result is not exactly consistent with the ones of Jlassi and Bensaïda (2014), Huang, Lin, and Yang (2015), Economou, Katsikas, and Vickers (2016). The possible reason is that the 1997–1998 Asia financial crisis did not make too large attack to the Taiwan stock market. Besides, Kaminsky and Schmukler (1999) indicated that the Asian stock markets were soaring in the early 1990s with a daily average of 0.04%. However, in the period of January 1997 to May 1998, in spite of the positive daily average of 0.01% in the Taiwan stock market, the daily averages of other Asia stock market are all negative. Therefore, the attack of 1997–1998 Asia financial crisis is relatively small to the Taiwan stock market. According to the empirical results, this study finds that the promotion of IDTRs of the financial supervisory institution has the positive influence on financial market. Besides, the management could mitigate the irrational shock of stock prices by enhancing the transparency of the corporations. Finally, this study suggests that the future research might take the styles of investors into consideration to explore. EFFECTS OF TRANSPARENCY ON HERDING BEHAVIOR 19 Acknowledgments We acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions from the anonymous reviewers. Funding This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology [104-2815-C-468-036-H]. Notes 1. According to the information cascade theory, herding occurs when observant investors ignore the information they possess and follow others’ decisions (Banerjee 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirsheifer, and Welch 1992; Demier, Kutan, and Chen 2010). 2. Taking Equation 3 for example, if β2,f is statistically significantly negative, then the more (Rm,t)2, the less CASDf,t. From the financial intuition viewpoint, it means that when market returns are getting higher or lower, investors might abandon their own experimental judgments, and make their investment decisions by macro-economic environment. Then, the more of (Rm,t)2 might make the deviations of the stock returns smaller, and produce the nonlinearly incrementally decreasing phenomenon (Chang, Cheng, and Khorena, 2000). This phenomenon is regarded as a result of herding behavior of investors. References Banerjee, A. V. 1992. A simple model of herd behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (3):797–817. doi:10.2307/ 2118364. Bikhchandani, S., D. Hirsheifer, and I. Welch. 1992. A theory of fads, fashion, custom and cultural change as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy 100 (5):992–1026. doi:10.1086/261849. Bikhchandani, S., and S. Sharma. 2000. Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Economic Review 47 (3):279–310. doi:10.2307/3867650. Caparrelli, F., A. M. D’Arcangelis, and A. Cassuto. 2004. Herding in the Italian stock market: A case of behavioral finance. Journal of Behavioral Finance 5 (4):222–30. doi:10.1207/s15427579jpfm0504_5. Chang, E. C., J. W. Cheng, and A. Khorana. 2000. An examination of herd behavior in equity markets: An international perspective. Journal of Banking & Finance 24 (10):1651–79. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(99)00096-5. Chiang, T. C., and D. Zheng. 2010. An empirical analysis of herd behavior in global stock markets. Journal of Banking & Finance 34 (8):1911–21. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.12.014. Chiang, T. C., J. Li, L. Tan, and E. Nelling. 2013. Dynamic herding behavior in Pacific-Basin markets: Evidence and implications. Multinational Finance Journal 17 (3/4):165–200. doi:10.17578/17-3/4-3. Choe, H., B. C. Kho, and R. M. Stulz. 1999. Do foreign investors destabilize stock markets? The Korean experience in 1997. Journal of Financial Economic 54 (2):227–64. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(99)00037-9. Choi, N., and H. Skiba. 2015. Institutional herding in international markets. Journal of Banking & Finance 55:246–59. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.02.002. Christie, W. G., and R. D. Huang. 1995. Following the pied piper: Do individual returns herd around the market? Financial Analysts Journal 51 (4):31–37. doi:10.2469/faj.v51.n4.1918. Chung, H., W. Q. Judge, and Y. H. Li. 2015. Voluntary disclosure, excess executive compensation, and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance 32:64–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.04.001. Demier, R., A. M. Kutan, and C. D. Chen. 2010. Do investors herd in emerging stock markets? Evidence from the Taiwanese market. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 76 (2):283–95. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.06.013. Economou, F., E. Katsikas, and G. Vickers. 2016. Testing for herding in the athens stock exchange during the crisis period. Finance Research Letters 18:334–41. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2016.05.011. Erkens, D. H., M. Hung, and P. Matos. 2012. Corporate governance in the 2007-2008 financial crisis: Evidence from financial institutions worldwide. Journal of Corporate Finance 18 (2):389–411. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2012.01.005. Froot, K., D. Scharfstein, and J. Stein. 1992. Herd on the street: Information inefficiencies in a market with short-term speculation. Journal of Finance 47 (4):1461–84. doi:10.2307/2328947. Hsieh, S. F. 2013. Individual and institutional herding and the impact on stock returns: Evidence from Taiwan stock market. International Review of Financial Analysis 29:175–88. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2013.01.003. Hsu, C. H., S. C. Lai, and H. C. Li. 2016. Institutional ownership and information transparency: Role of technology intensities and industries. Asia Pacific Management Review 21 (1):26–37. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2015.06.001. Huang, T. C., B. H. Lin, and T. H. Yang. 2015. Herd behavior and idiosyncratic volatility. Journal of Business Research 68 (4):763–70. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.025. Hwang, S., and M. Salmon. 2004. Market stress and herding. Journal of Empirical Finance 11 (4):585–616. doi:10.1016/j. jempfin.2004.04.003. Jlassi, M., and A. Bensaïda. 2014. Herding behavior and trading volume: Evidence from the American Indexes. International Review of Management and Business Research 3 (2):705–22. 20 K.-Y. WANG AND Y.-S. HUANG Kaminsky, G. L., and S. L. Schmukler. 1999. What triggers market jitters? A chronicle of the Asian crisis. Journal of International Money and Finance 18 (4):537–60. doi:10.1016/S0261-5606(99)00015-7. Keynes, J. M. 1936. The general theory of employment, interest and money. New York: Macmillan. Lakonishok, J., A. Vishny, and R. W. Vishny. 1992. The impact of institutional trading on stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics 32 (1):23–43. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(92)90023-Q. Lee, H., H. L. Lee, and C. C. Wang. 2017. Engagement partner specialization and corporate disclosure transparency. International Journal of Accounting 52 (4):354–69. doi:10.1016/j.intacc.2017.10.001. Lee, H. L., and H. Lee. 2015. Effect of information disclosure and transparency ranking system on mispricing of accruals of Taiwanese firms. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 44 (3):445–71. doi:10.1007/s11156-013-0413-5. Nofsinger, J., and R. Sias. 1999. Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. Journal of Finance 54 (6):2263–95. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00188. Ramli, I., S. Agoes, and I. R. Setyawan. 2016. Information asymmetry and the role of foreign investors in daily transactions during the crisis; A study of herding in the Indonesian Stock Exchange. The Journal of Applied Business Research 32 (1):269–88. Scharfstein, D. S., and J. C. Stein. 1990. Herd Behavior and Investment. American Economic Review 80:465–79. doi:10.19030/ jabr.v32i1.9537. Securities and Futures Institute. 2013. Information disclosure and transparency ranking results report. Accessed May 2, 2015. http://t.cn/RdoAmvU. Securities and Futures Institute. 2015. Data from: 2005-2014 Information disclosure and transparency ranking results in Taiwan [dataset]. Securities and Futures Institute Website. Accessed May 2, 2015. http://www.sfi.org.tw/cga/cga2. Shleifer, A., and L. H. Summers. 1990. The noise trader approach to finance. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (2):19–33. doi: 10.1257/jep.4.2.19. Shyu, J., and H. M. Sun. 2010. Do institutional investors herd in emerging markets? Evidence from the Taiwan stock market. Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting 2 (2):1–19. doi:10.5296/ajfa.v2i2.456. Sias, R. W. 2004. Institutional herding. Review of Financial Studies 17 (1):165–206. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhg035. Tan, L., T. C. Chiang, J. R. Mason, and E. Nelling. 2008. Herding behavior in Chinese stock markets: An examination of A and B shares. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 16 (1–2):61–77. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2007.04.004. Yao, J., C. Ma, and W. P. He. 2014. Investor herding behavior of Chinese stock market. International Review of Economics and Finance 29:12–29. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2013.03.002. Zhou, R. T., and R. N. Lai. 2009. Herding and information based trading. Journal of Empirical Finance 16 (3):388–93. doi:10.1016/j.jempfin.2009.01.004.