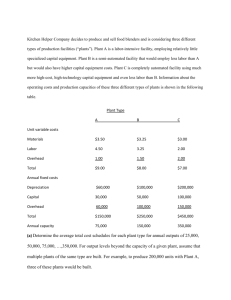

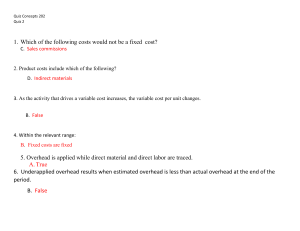

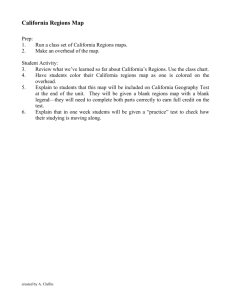

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263565067 Managing overhead in public sector organizations through benchmarking Article in Public Money & Management · January 2014 DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2014.865929 CITATIONS READS 10 1,302 3 authors, including: Arno Geurtsen Jan van helden Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam University of Groningen 2 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS 122 PUBLICATIONS 1,895 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: The role of accounting information in the dynamics of decision making about controversial projects in public and non-profit sectors View project Design, implementation and use of performance management in the public sector View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jan van helden on 11 August 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. This article was downloaded by: [University of Groningen] On: 30 November 2013, At: 05:22 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Public Money & Management Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpmm20 Managing overhead in public sector organizations through benchmarking Mark Huijben, Arno Geurtsen & Jan van Helden Published online: 29 Nov 2013. To cite this article: Mark Huijben, Arno Geurtsen & Jan van Helden (2014) Managing overhead in public sector organizations through benchmarking, Public Money & Management, 34:1, 27-34, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2014.865929 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2014.865929 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http:// www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions 27 Managing overhead in public sector organizations through benchmarking Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 Mark Huijben, Arno Geurtsen and Jan van Helden Many public sector organizations struggle with the size of their overhead. The current crisis has forced them to cut costs, but how drastic can these cuts be without losing too much value? In 2001, we started an overhead benchmarking project in the Netherlands and by 2012, 1,500 public sector organizations had participated in the study. This paper shows how benchmarking of overhead costs helps organizations to understand and properly balance the costs and benefits of their overhead functions. Keywords: Benchmark; overhead; overhead benchmark; overhead value analysis (OVA). Overhead is a phenomenon that many people dislike; it is often associated with the ‘fat’ of an organization and one of our interviewees labeled it as ‘self-rising flour’. Nevertheless, it fulfills an important function, namely steering and supporting an organization’s primary processes. Overhead is also an emotionallycharged subject and discussions about the issue often stir up strong feelings. The notion of too much overhead aggravates people because it is associated with a loss of financial resources for primary processes. Moreover, not everybody recognizes its added value, while the emotions of the employees involved in overhead functions run high every time drastic overhead cuts are made without a thorough analysis. Many organizations have problems with their overhead functions and find the issue hard to get a grip on. In this respect, there are a number of recurring questions: •Which functions can be considered as overhead? •What is the size of my overhead relative to that of comparable organizations? •Should I expand this or that overhead department or not? •Is there still room for cuts? •How can I determine the optimal size of my overhead? There is very little expert literature available on managing overhead; to date we have located only one paper on benchmarking overhead (Goold and Collis, 2005) and that paper concentrates on the overhead of an organization’s head office whereas decentralized overhead can also be extensive. Most academic work has involved assigning overhead costs (Rogerson, 1992; Armistead, 1995; Durden and Mak, 1999; van Helden, 2000; Luther and Robson, 2001; McGowan and Vendrzyk, 2002; MacArthur et al., 2004; Heitger, 2007). In this paper we present an unambiguous method for measuring and comparing public sector organizations’ overhead. We argue that measurement and comparison are essential steps in the management of overhead. After benchmarking costs and analysing the value of an organization’s overhead functions, top management can balance the costs and value of their overhead. What makes overhead so difficult to manage? Overhead is an intangible phenomenon (Allen, 1987; Sanders, 2003; Drury and Tayles, 2005; Pellicer, 2005; Norfleet, 2007) that is difficult to grasp for a number of reasons. First, it is difficult to establish which parts of an organization can be labeled as overhead. In addition, overhead differs by organization. The personnel involved in preparing meals for staff at a municipality will, for example, be considered as overhead, whereas in a hospital the same tasks are regarded as an essential part of patient care. There is no common definition; tasks considered to be overhead by one organization may not be regarded as such by others. In practice, each individual organization has its own description of overhead, which leads to confusion. Second, overhead is comprised of a large number of different tasks executed across the Mark Huijben works for Berenschot Consultancy in the Netherlands. Arno Geurtsen is affiliated with the Free University Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Jan van Helden is emeritus professor in management accounting at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2014.865929 © 2014 CIPFA PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 28 organization as a whole, partly centrally but generally also at multiple decentralized locations. This situation undermines the transparency of the concept. The definition of overhead can range from cleaning personnel, people who make sandwiches in a canteen, internal mail delivery and an IT helpdesk to personnel policies, the treasury function and management. The third problem is that overhead tasks change over time. For example, smartphones did not exist in the 1970s; instead, telexes were heavily used. Hence, the supporting tasks also change over the years. A first step in managing overhead is defining the concept in order to determine its size within the individual organization. What is overhead? In 2001, we developed the first draft of the definition of overhead functions, based on our knowledge of public sector organizations. This draft was presented to a representative group of controllers of Dutch municipalities and welfare organizations. We then further developed our definition in group sessions. Afterwards, we asked about 25% of those municipalities to fill in the forms we had developed for measuring overhead. We then further refined our definition. The academic literature provides two basic definitions of overhead: direct versus indirect costs (overhead); and primary versus secondary activities (overhead). Although a fundamentally different definition does not need to be added, there is a need for clarification. The first definition, the distinction between direct and indirect costs, is not very clear, because the question of which costs are direct or indirect largely depends on an organization’s structure and administrative system. Some organizations measure the use of particular support services by primary services, while others allocate the costs of those support services to the primary services. In the first case, the costs of support services are direct costs, while in the latter case they are indirect costs. So, because organizations differ largely in what they consider to be indirect costs, this hinders a proper comparison. The second definition, the distinction between primary and secondary services or activities, is a generally suitable point of departure. A proper comparison is, however, only possible if this definition is specified in sufficient detail. Moreover, it should take into account the differences between sectors. It is from this perspective that we present our PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 definition of overhead (Huijben and Geurtsen, 2008). We define overhead as the whole of functions aimed at steering and supporting employees in the primary process. Therefore, overhead functions indirectly contribute to the organization’s functioning. In this respect we distinguish between generic overhead and sectorspecific overhead. Generic overhead is common in every sector, while the nature of sectorspecific overhead differs by sector. This distinction is important in order to adequately compare the overhead of organizations in different sectors. Generic overhead The concept of generic overhead typically includes functions that are common in all sectors. Our definition includes all centralized and decentralized departments dealing with the following functions: board, management, and secretarial support; personnel affairs/ human resources (HR); IT; finance and control; communication; legal affairs; facility services, for example security, maintenance, delivery of internal mail, and reception desk services. These activities are only considered to be overhead insofar as they do not form part of the organization’s primary tasks. This applies to some of the functions mentioned here, as the following examples illustrate: We characterize the restaurant in a municipal organization as ‘overhead’ because it serves the employees in the primary process rather than the citizens. The restaurant in a nursing home is considered mainly a ‘primary process’ because it exists to serve the residents of this institution. It only serves the organization’s employees to a limited degree, so it can only partly be characterized as overhead. Specific overhead This concept relates to the particularities of a certain sector, in the sense that overhead concerns those specific functions that fit the basic definition but only apply to one particular sector. For example, universities need ‘student support’ (which includes sports instructors and psychologists for students) and ‘educational administration’ functions. The work of a courtroom messenger may serve as another example—the messenger supports the primary process of the courtroom. This type of work is not relevant in other sectors, so it is a sectorspecific overhead function. © 2014 CIPFA 29 Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 Approach and methods of data collection Our approach to controlling overhead has five steps: 1. Defining the overhead: what should be considered to be overhead and what should not? 2. Measuring the overhead: what is the amount of overhead in an organization in terms of full-time units (FTUs) and costs? 3. Benchmarking the overhead’s size: what is the size of an organization’s overhead relative to that of organizations in the same sector? 4. Cost-benefit analysis for overhead functions. This analysis is based on the benchmark and additional research focused on deviations from the benchmark. The central question is to what extent are the deviations are justified by the value of these functions? We deliberately do not start from a pre-defined definition of overhead value, because relevant dimensions may differ among organizations. For example, one organization may prefer a sober office to a more luxurious one (to show that they do not waste money), while another one may want an image that reflects wealth and success. Another example of a dimension might be the proximity or distance of the organization’s location relative to that of certain other organizations. So, the measurement of overhead value takes place after the relevant dimensions have been mapped out in consultation with the organization. 5. Taking concrete measures to find a better balance between the costs and benefits of the overhead functions. This often requires adjusting the service provision level, improving the way in which these services are produced and rearranging the overhead functions. Going through these steps will clarify which tasks in an organization’s overhead deviate from other organizations and why. The benchmark indicates whether follow-up research would be useful and what it should focus on. The additional research in step 4 is based on existing methods, for example overhead value analysis (Neuman, 1975) and activity based costing (Kaplan and Bruns, 1987). Steps 1 and 2 are based on desk research, literature reviews and feedback from practitioners about preliminary definitions of overhead and overhead functions. Step 3, the overhead benchmark, is based on surveys of organizations in various sectors. After the © 2014 CIPFA overhead benchmark has been determined, more indepth case studies for selected organizations are carried out in order to elaborate Step 4, the cost-benefit analysis of overhead functions, and Step 5, the consideration of actions to improve the balance between the costs and benefits of overhead functions. These studies are based on interviews with managers from both overhead and primary process departments, as well as financial documents pertaining to the various overhead functions. Measuring overhead Overhead is measured in FTUs. The number of FTUs used to execute overhead tasks is divided by the total number of FTUs in the organization. Although there are other possible denominators, our research has shown that the total number of FTUs in an organization is the main cost driver of the overhead workload. Moreover, FTUs can be measured relatively unambiguously in comparison with other variables, such as costs. In addition to the number of overhead FTUs, the following costs are listed: salary costs of overhead personnel; costs of outsourcing overhead activities and hiring personnel; material costs of overhead functions; and facility costs. In order to map out an organization’s total overhead, these costs are also expressed per organizational FTU. An alternative for the total amount of FTUs of an organization is the amount of FTUs in the primary process. This denominator, however, has two disadvantages. First, in addition to primary functions, overhead functions will also generate work in the sphere of overhead. For example, a human resources officer will need IT support, a workplace, a restaurant, etc. Second, this denominator is more difficult to communicate to the people in the organization, since it is dependent on the amount of overhead. Benchmarking overhead Benchmarking an organization’s overhead means that one organization’s overhead data are compared data collected from other organizations in the same sector. This enables us to determine the size of an organization’s overhead compared to that of organizations in the same sector or in other sectors. Since 2001, we have developed a database about the overhead size in more than 1,500 organizations in the Netherlands. Figure 1 shows that there are considerable differences in the amount of overhead among the sectors, of which 25 (of a total of 32) belong to the public and non-profit PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 30 Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 sectors. Ministries and municipalities have, for example, a relatively high overhead, while health care and educational organizations are characterized by a relatively low overhead. In all sectors we disregarded the sector-specific overhead, so the large differences between the sectors were not caused by differences in the definition. Furthermore, figure 2 indicates that substantial variations in overhead size also exist between organizations in the same sector: the maximum overhead in a sector is often twice as high as the minimum overhead. Explanations for the differences between sectors and organizations within the same sector We conducted a series of structured interviews with the organizations included in the research in order to find out what influenced the number of overhead FTUs. Relevant factors which affect the amount of overhead are: 1. The sector to which the organization belongs. Every branch has its specific characteristics that explain the differences in the amounts of overhead, such as specific rules and laws, a specific approach to accountability or a specific IT infrastructure. Courts, for example, need relatively high levels of security and huge archives. But, on the other hand, the financial accountability of Dutch courts is simple, resulting in small finance departments. Local governments have relatively complex accountability obligations due to a diversity of laws and the political dimension, resulting in large finance departments. 2. The control philosophy (the way of steering and controlling the organization). Lewy (1992) distinguishes between ‘tight control’ and ‘loose control’. Both control styles influence the number of FTUs deployed in the management of an organization. In a tight control situation, the organization pays a lot of attention to supervision and monitoring, whereas an organization with loose control pays less attention to these issues. 3. The overhead departments’ service provision levels. Some organizations have opted for a minimum provision of support and others for more extensive facilities. There are organizations where even board members do not have their own offices, where there is no restaurant and where the secretarial staff only performs standard tasks. In other organizations, however, all managers have luxurious offices, the employees can have their lunch in the restaurant for free and PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 there is a secretarial staff to whom managers can dictate letters and notes from their cars. In one organization, any employee can order goods from any supplier, whereas another has strict procedures in this respect. 4. The historical development of overhead and the prevailing culture. Organizations get used to a certain type of overhead. If it is normal that each manager has a secretary and an assistant manager, these matters often become highly sensitive and are not easily discussed. There are also organizations which have retained the traditional overhead functions (a library, an office for text processing) that other companies have abandoned. For most organizations these kinds of functions are no longer strictly necessary. 5. The organization of overhead. There is no denying that some organizations are far more efficient than others. As overhead tasks are more dispersed across various departments, a higher level of task distribution is required. In particular, the co-ordination between centralized and decentralized overhead departments is often insufficient. As a result, the same tasks are duplicated and much time is lost on consultations. In addition, we see that the decentralized managers’ discontent regarding these issues leads to the decentralized appointment of people for staff functions with the aim of regaining ‘control’. This is, of course, undesirable for the organization as a whole. 6. The affordability of overhead plays an important role. Organizations that can afford a large overhead will not be inclined to reduce the amount of overhead personnel. Organizations that cannot afford overhead, however, will try to reduce it. Examples of ‘rich’ organizations in the Netherlands are housing corporations and ministries. It was striking to see how surprised the top managers of these organizations were when they were confronted with their high overhead costs. On the other hand, we analysed the overhead of a large welfare organization that was forced to reduce its overhead because the local government did not want ‘to spend money on overhead’. However, our research showed that the overhead costs were already low and further funding cuts bankrupted the welfare organization. We also investigated whether the size of the organization measured in FTUs is a significant driver for overhead variation. Managers and officials in the public sector often believe that a © 2014 CIPFA Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 31 larger organization leads to lower overhead costs per FTU, while economic theory supposes a U-form of the overhead costs per FTU as a function of organizational size. However, we found that this relationship is basically linear: the larger the number of FTUs, the larger an organization’s overhead. In contrast with the expectations, economies of scale hardly occur (as figure 3 illustrates). A large municipality has, for instance, on average about the same percentage of overhead as a small municipality with 150 officials. Only very small municipalities have relatively higher overheads. The huge differences in the amount of overhead among the organizations that we observed (see figures 1 and 2) can only partly be explained by rational arguments (factors 1, 2 and 3 above). The irrational factors 4 and 6 (and partly also 5) reveal why organizations do not cut their overhead even when it is clearly possible. To illustrate this we present some interview quotations. ‘Overhead is not an issue here,’ said a human resources director of a law office, when we confronted him with his large number of secretaries (25% of the total FTU). ‘We think in billions here’ indicated a board member of a financial institution, when we made clear that he could save millions on overhead. Cost-benefit analysis for overhead functions Table 1 presents a cost-benefit analysis for overhead functions. The table distinguishes between two variables that determine the search process for an improved combination of the costs and benefits of overhead functions: the service level and the cost level. For both variables, three value categories are distinguished (i.e., low, medium and high), which results in nine value combinations. These value combinations are presented in the table cells numbered 1 through 9. Four types of value combinations emerge from the table: •A balanced combination of costs and benefits (cells 1, 5 and 9). •An efficient combination of costs and benefits (cells 4 and 8) in which the service level is relatively higher than the cost level. •An inefficient combination of costs and benefits (cells 2 and 6) in which the service level is relatively lower than the cost level. •An unlikely combination of costs and benefits (cells 3 and 7) in which the service level is substantially higher or lower than the cost level. Depending on where in the table an © 2014 CIPFA Figure 1. Amount of overhead. Figure 2. Variation in overhead size (minimum—maximum). organization’s costs and benefits of overhead functions lies, two types of decisions can be considered. First, if an organization holds an inefficient position, it has to consider either cost reduction actions or benefit improvement actions, which result in: starting in cell 2, a move from 2 to 1 (cost reduction) or from 2 to 5 (benefit improvement); and starting from cell 6, a move from 6 to 5 (cost reduction) or from 6 to 9 (benefit improvement). Second, an organization can move from one to another balanced position. These are diagonal moves between cells 1, 5 and 9. The cost level is based on the benchmark and the service level is based on an Overhead Value Analysis (OVA). The service level should fit the demands of the organization (managers and employees). Therefore, an important part of conducting the OVA is interviewing suppliers and demanders. An OVA includes: 1. Mapping out the tasks of the overhead functions in a detailed manner and calculating the staff and costs per task. PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 32 Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 Figure 3. Economies of scale in overhead. 2. Determining the value of the overhead tasks on the basis of interviews with the internal purchasers and providers. Here the focus is on the internal purchasers’ appraisal, as well as the providers’ and purchasers’ perception of the value of the overhead tasks for the organization as a whole. This step may concern issues such as unburdening the employees in the primary process, legal requirements, contributing to the organization’s image or other organizational objectives (Huijben, 2011). 3. On the basis of steps 1 and 2, the organization’s board is subsequently able to make a comparison between overhead costs on one hand and its value on the other. The following case study illustrates how a particular organization has dealt with a partly inappropriate balance between the costs and benefits of its overhead functions. Case study: Centre for Educational Service Provision (CESP) CESP primarily provides supervisory and training services to professionals working in various types of schools. Formerly, CESP was part of the Rotterdam local government organization, but it became an autonomous entity in 2002 and as such has since received both subsidies and project-related payments for its services. In 2009, CESP’s top management approached one of the authors for advice about possible interventions in the organization’s overhead functions. At that time, CESP employed about 200 people, all working at one location. Because CESP was in transition from a governmental to a market organization, it preferred to benchmark its overheads with private sector service organizations, in particular with the ‘research, engineering, and architecture’ and ‘financial services’ sectors, whose activities were considered to be similar to CESP’s operations. After consulting the organization’s general director, the financial director and an internal consultant, three overhead functions were selected for further analysis, mainly because their costs and benefits seemed not to be balanced: •Management (with an overhead of 50% above the sector average). •Knowledge management (because this function had been criticized and in many organizations this function was integrated into the primary process). •IT (the problem here was that this service was expected to support a relatively large number of part-time functions, while its overhead costs were 25% below the sector average). Each of these functions is further discussed below. CESP had three management layers: a general director, functional and market-related directors, and unit managers (also called team co-ordinators). During our interviews, employees complained about the large number of managers and an unclear division of responsibilities among the three management layers. Managers also had responsibilities that were part of advisors’ responsibilities in other consultancy organizations, such as project planning. Therefore, CESP wanted to reduce the number of management layers in combination with the number of managers and transfer some management functions to the advisors. This required both reducing and redesigning overhead functions. The knowledge managers expressed their Table 1. Cost-benefit analysis of overhead functions. Cost level (based on the sector benchmark) Service level (based on an OVA) PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 Low Medium High Low Medium High 1. Balance 4. Efficient 7. Unlikely 2. Inefficient 5. Balance 8. Efficient 3.Unlikely 6. Inefficient 9. Balance © 2014 CIPFA Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 33 way of working in two policy documents. In order to arrive at this, they organized meetings with managers and experts within CESP. So, although there were various safeguards to ensure a good relationship between the knowledge managers and their internal clients, the knowledge managers’ work did not receive much appreciation from these clients. The extreme option of abolishing knowledge management as a separate overhead function and integrating it into the primary process was not supported. The CESP board ultimately decided to continue with the current way of working and to reduce the number of knowledge managers from three to two FTUs. The IT function involved co-operation between internal IT employees and an external party. There was no clear policy indicating which IT facilities were available to the employees. Neither was there an organized form of consultation between line managers and IT employees regarding this issue. As a result, it was difficult for the external party and the internal IT staff members to do their work. This resulted from lack of support and the unclear policy, but was also due to the demanding attitude the advisors had when dealing with the IT employees. A provider– user interface was seen as a more desirable approach, because it offered clarity to the supplier and the user about the preferred/ expected level of the service provision. The IT department developed project and investment plans to reach this new service level. Further illustrations Some brief examples from other case studies may further illustrate cost-benefit analysis of overhead functions. A supervising institution was faced with a relatively high cost level in its finance department and reduced its size in combination with better attuning its information provision to the line managers’ need for information. The large size of a high council of state’s personnel department was not changed because it could be clearly explained by the fact that the organization facilitated its own training courses. However, a child welfare organization reduced its facility costs by replacing a number of fixed workplaces with flexible ones. The main advantage of measuring and comparing overhead is that discussions can be based on facts rather than emotions. This allows the costs and benefits to be weighed: can the higher costs be justified on the basis of the service provision or is this impossible? Various types of answers can be given, as our illustrations show, ranging from repositioning overhead © 2014 CIPFA functions (centralized versus decentralized) and adjusting the internal demanders’ expectations about the extent and type of overhead functions so that they are more realistic about what is possible. Reflections and suggestions for further research This paper has developed an approach for mapping out an organization’s overhead in an unambiguous manner. The objective of identifying overhead is to make the issue accessible and manageable. Once the factual size of the overhead has been established, management can benchmark the overhead and use it to determine the extent to which an organization’s current overhead deviates from that of other organizations in the same sector. Based on this comparison, it can decide whether or not to adjust the overhead. Here, OVA can be used to diagnose and determine a proper trade-off between the cost and value of overhead functions. Deviating from other organizations’ overhead levels does not have to be problematic, but it should be a deliberate choice. To what extent does this approach actually lead to the improvement of an organization’s decision-making process with respect to overhead? On one hand, our observations during the past 10 years indicate that using this approach concentrates the overhead discussion more on factual figures and the causes of overhead cost differences compared to other organizations. An increasing number of organizations currently base their decisions on the benchmark figures, and many organizations have embedded the approach developed here into their planning and control cycle. In 2009, for example, all Dutch courts followed this approach. This also applies to many municipalities; since 2006, the Dutch Municipalities Association (Vereniging Nederlandse Gemeenten) has awarded our overhead benchmark a quality mark and has actively brought it to the attention of all municipalities. Moreover, the Dutch central government has used our method to determine its output funding of all 14 universities since 2011. On the other hand, we have observed a kind of asymmetry in the adoption of our overhead management approach. All organizations that use this approach are interested in unambiguously defining their overhead, measuring their overhead costs and benchmarking figures about those costs. However, only a minority of these organizations are using OVA. In the period before the PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 34 Downloaded by [University of Groningen] at 05:22 30 November 2013 financial crisis in 2008, we frequently found that if organizations generally had lower overhead costs than their sector average, they considered that to be a confirmation of good practice and were not inclined to take corrective actions. However, if organizations had higher overhead costs than their sector average, many of them produced arguments to justify their existing practices. Consequently, overhead benchmarking offered a path for defensive behavior, as was also observed in a more general sense regarding public sector benchmarking operations (Bowerman and Ball, 2000; Llewellyn and Northcott, 2005; Tillema, 2010). Due to the financial crisis, we have also recently seen an extremely contrasted reaction pattern in which financial stress leads organizations to use overhead benchmarking cost figures (in the form of best-in-class figures) as targets for their future overhead cost levels, without seriously looking at potential losses in value due to cost reductions. This pattern also differs between sectors: surprisingly, sectors with a low average generic overhead were more inclined to look at possible actions to cut costs than sectors with a high overhead. This could be due to differences in financial pressure. For example, the financial pressure on sectors such as care and primary education is high; Dutch media and politics usually dishonestly criticize the ‘huge amount of overhead’ in these sectors. We observed that this criticism and financial pressure leads these organizations to try to cut costs, even when this is no longer possible. Further research should question the extent to which international differences determine the size of overhead. In addition, further study is required to obtain more insight into the large differences that exist in the management and design of overhead functions. References Allen, B. (1987), Make information services pay its way. Harvard Business Review, 65, 1, pp. 57–63. Armistead, C. G. et al. (1995), Managers’ perceptions of the importance of supply, overhead and operating costs. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 15, 3, pp. 16–28. Bowerman, M. and Ball, A. (2000), Great expectations: benchmarking for best value. Public Money & Management, 20, 2, pp. 21–26. Drury, C. and Tayles, M. (2005), Explicating the design of overhead absorption procedures in UK organizations. British Accounting Review, 37, 1, pp. 47–84. Durden, C. H. and Mak, Y. T. (1999), Reporting of PUBLIC MONEY & MANAGEMENT JANUARY 2014 View publication stats overhead variances: a cost management perspective. Journal of Accounting Education, 17, 2–3, pp. 321–331. Goold, M. and Collis, D. (2005), Benchmarking your staff. Harvard Business Review, 83, 9, pp. 28– 30. Heitger, D. L. (2007), Estimating activity costs: how the provision of accurate historical activity data from a biased cost system can improve individuals’ cost estimation accuracy. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 19, pp. 133–159. Helden, G. J. van (2000), A strategy for implementing cost allocation in a Dutch municipality. In Caperchione, E. and Mussari, R. (Eds), Comparative Issues in Local Accounting (Kluwer Academic, Boston), pp. 125–141. Huijben, M. P. M. and Geurtsen, A. (2008), Heeft iemand de overhead gezien? Een beproefde methode om de overhead te managen (Has anyone seen the overhead? A tested method to manage overhead), (Academic Service, The Hague). Huijben, M. P. M. (2011), Overhead Gewaardeerd [Overhead rated] (PhD thesis, University of Groningen). Kaplan, R. S. and Bruns, W. (1987), Accounting and Management: A Field Study Perspective (Harvard Business School Press, Harvard). Lewy, C. P. (1992), Management Control Regained (Kluwer, Deventer). Llewellyn, S. and Northcott, D. (2005), The average hospital. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30, 6, pp. 555–583. Luther, R. and Robson, N. (2001), Overhead allocation: a cautionary tale. Accounting Education. 10, 4, pp. 413–419. MacArthur, J. et al. (2004), Caution; fraud overhead. Strategic Finance, 86, 4, pp. 28–32. McGowan, A. S. and Vendrzyk, V. P. (2002), The relation between cost shifting and segment profitability in the defense-contracting industry. Accounting Review, 77, 4, pp. 949– 969. Neuman, J. L. (1975), Make overhead cuts that last. Harvard Business Review, 53, 3, pp. 116–126. Norfleet, D. A. (2007), The theory of indirect costs. AACE International Transactions, pp. 12.1–12.6. Pellicer, E. (2005), Cost control in consulting engineering firms. Journal of Management in Engineering, 21, 4, pp. 189–192. Rogerson, W. P. (1992), Overhead allocation and incentives for cost minimization in defense procurement. Accounting Review, 67, 4, pp. 671–690. Tillema, S. (2010), Public sector benchmarking and performance improvement; what is the link and can it be improved? Public Money & Management, 30, 1, pp. 69–75. © 2014 CIPFA