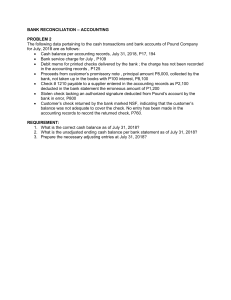

F341 2018 1 As an investor (or investment advisor), the ultimate goal is to choose the portfolio that is “optimal.” ◦ How do you know what is optimal for a particular investor? (Preferences) ◦ How do we evaluate risky assets? (Risk and return measurement) ◦ Given preferences and asset characteristics, how do we select a portfolio? (Optimization) F341 2018 2 Prior to the 1950’s, investment analysis was largely non-quantitative and unscientific. ◦ “The wise man puts all his eggs in one basket and watches the basket.” Andrew Carnegie\Mark Twain Harry Markowitz’s path-breaking work in the 1950’s revolutionized portfolio theory. ◦ Why would any rational person take on greater risk unless compensated by greater expected return? F341 2018 3 Obviously, they range from very sophisticated (particularly for large institutions) to some very silly approaches (some financial planners, some online firms) Today’s approach will (hopefully) fit with the former group. Let’s briefly look at the latter group. The following is constructed from several online “optimizers.” F341 2018 4 Current Age 50 Current Savings $100,000 Annual Savings (today’s $) $12,000 Retirement Age 65 Annual Retirement Spending (today’s $) $70,000 Years in Retirement 20 Investment Return 10.5% Inflation (%) 3.5% F341 2018 5 What’s with the “years in retirement” input? Is this a polite way of asking someone when they plan on dying? The user inputs the all-important investment return number? ◦ This is like going to the doctor with a headache, and the doctor asking you if it is a tumor. Is there any notion of risk? F341 2018 6 Congratulations! Your plan works. F341 2018 7 Warning! Your plan does not work. F341 2018 8 Save more Retire later Spend less Increase investment return 1. 2. 3. 4. The first 3 seem kind of unpleasant. Why not simply choose a higher return? ◦ Note that a fifth potential solution is to die sooner. F341 2018 9 You typically get pie charts of the following variety: Where did this come from? F341 2018 10 In a later module, we will look more deeply at “life-cycle” or dynamic investing. In this module, we’ll focus on a quantitative approach to trading-off risk and return, in a manner that best suits an investor’s tastes. F341 2018 11 A risky asset (or portfolio) is simply one where its return is not known with certainty. Mathematically, we say that the return on a risky asset is a random variable. F341 2018 12 You can’t describe a risky return with simply one number. In general, one uses a probability distribution. We shall find that 2 metrics are most helpful for describing risky returns: expected returns and variances. We denote asset i’s expected return and variance as: 2 E (r ) and i i F341 2018 13 The expected return is the mean, or average return. Since we don’t know the true E(ri), we must estimate it. F341 2018 14 One naïve method is to simply use the historical average return. That is, if you look at asset i’s historical returns over periods 1, 2, … , T, its historical average return is: 1 r r T T i t 1 i ,t F341 2018 15 Historical average returns are notoriously unreliable. For example, if you compute an average return over one 5-year period, it will provide little guidance for what will take place over the following 5-year period. Typically, we use equilibrium models or economic judgment to compute expected returns. We will see some of this today. F341 2018 16 Variance measures the degree of spread of a distribution around its expected value. Again, we do not know , so we must estimate it. The standard estimator using historical data is: 2 i S 2 i 1 r r T 1 2 T t 1 i ,t i and the estimator of standard deviation is simply its square root, Si. F341 2018 17 Historical estimations of variances are also imperfect. There are a wide variety of estimation techniques that improve upon the simple one just described (GARCH, factor models, implied volatility) That being said, the historical estimate of variance is much more predictive than the historical estimate of expected return. F341 2018 18 Finally, we also need a measure of the degree to which assets’ returns co-move. We denote the covariance between assets i and j as . A positive (negative) covariance implies that when one asset’s return is above its expected return, the other asset’s return is likely to be above (below) it expected return. The correlation between assets i and j is i,j i,j i,j i j F341 2018 19 The standard covariance estimator using historical data is: 1 C r r r r T 1 T i,j i ,t t 1 i j ,t j The estimate of correlation (Corri,j) is then: C Corr SS i,j i,j i j F341 2018 20 A portfolio is a set of weights w1, w2, … , wn on individual assets. It is a vector. The weights must sum to 1. For each selection of weights, the portfolio’s expected return and variance are determined. The expected return on a portfolio is equal to: E (r ) w E (r ) w E (r ) ... w E (r ) p 1 1 2 2 n n w E (r ) n i 1 i i Thus, the portfolio’s expected return is simply the weighted average of the individual asset’s returns. F341 2018 21 The variance of a portfolio is equal to: 2 p ww n n i 1 j 1 i j i,j The variance of a portfolio is complicated, since it must take into account covariances across all assets. F341 2018 22 If you have a negative weight in the risky portfolio, you are shorting that asset. You are essentially “borrowing” the risky asset. ◦ What is the most you can make when short-selling? ◦ What is the most you can lose when short-selling? While some investors engage in extensive shorting (hedge funds), many others abstain (most mutual funds) F341 2018 23 How do you measure someone’s preferences over portfolio returns? This is actually complicated. In microeconomics, we typically think of utility over consumption goods such as apples and cars. Mathematically, it would simply be a function such as u(apples, cars). Now, since portfolio returns are random variables, the mathematical mapping is considerably more complicated. F341 2018 24 For the most part, we will make a simplifying assumption about preferences that will permit us to use a very simple utility structure. We assume mean-variance preferences. 1. Individuals care only about expected return and variance. 2. They like higher expected return, and like lower variance. Note that if all asset returns are normally distributed, and investors are risk averse, mean variance utility will hold. However, in reality, return distributions deviate from normality. F341 2018 25 While any M-V utility function that is increasing in the mean and decreasing in the variance will work, we shall find it useful to use a simple, linear function. A very common mean-variance utility function is the following linear formulation: A u E (r ) 2 p 2 p The parameter A represents the investor’s degree of risk aversion. (Why the ½?) One starts with the mean, and then subtracts out a “penalty” for risk. The higher the risk aversion, the higher is the risk penalty. F341 2018 26 If A>0, the investor dislikes risk, and is risk averse. If A=0, the investor doesn’t care about risk, and is risk neutral. If A<0, the investor likes risk, and is risk seeking. We will almost always assume risk aversion. F341 2018 27 Consider the following thought experiment. ◦ Imagine a risky portfolio with a mean of 8% and a variance of 4%. ◦ Would you rather have that portfolio or a riskless asset paying 2%? What about 5%? ◦ Determine the riskless rate that would leave you indifferent. ◦ Suppose that riskless rate is 2.8%. Then we have: A .028 .08 .04 2 A 2.6 F341 2018 28 The individual’s optimization problem is to select the portfolio (weights) so as to maximize utility. Optimization (in general) involves an objective function, control variable(s), and constraints. F341 2018 29 Here the objective function is the meanvariance utility: A u E (r ) 2 p 2 p which now can be written as: A u w E (r ) w w 2 n i 1 n i i n i 1 j 1 i j i,j F341 2018 30 Here the control variables are the n weights. That is, all other aspects of the problem are beyond the investor’s control. ◦ Can you think of any potential real-world violation of this assumption? F341 2018 31 The standard constraint is that the weights sum to 1: n w i 1 i 1. The set of constraints can be expanded to account for short-sell constraints or the inclusion of upper and lower bounds. F341 2018 32 We write the investor’s portfolio problem as: A max w E (r ) w w 2 subject to n w1 , w2 ,...,wn n w i 1 i i 1 i i n n i 1 j 1 i j i,j 1. For this particular problem, one can solve it completely using basic calculus (Lagrange). However, as constraints are added, numerical optimization (Solver) is the way to go. F341 2018 33 You are currently deciding how to allocate your portfolio across the following 8 asset classes: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. US Bonds Foreign Bonds US Large Cap Growth US Large Cap Value US Small Cap Growth US Small Cap Value Foreign Equity (Developed) Emerging equity F341 2018 34 Expected return US Bonds Foreign Bonds US Large Cap Growth US Large Cap Value US Small Cap Growth US Small Cap Value Foreign Equity Emerging Equity Standard Deviation 4.00% 2.75% 10.76% 8.17% 10.91% 9.91% 4.70% 4.95% 3.32% 8.35% 15.40% 15.92% 20.31% 20.04% 18.64% 22.70% F341 2018 35 Foreign US Bonds Bonds US Bonds Foreign Bonds US Large Cap Growth US Large Cap Value US Small Cap Growth US Small Cap Value Foreign Equity Emerging Equity US Large US Small Cap US Large Cap US Small Foreign Growth Cap Value Growth Cap Value Equity Emerging Equity 1.00 0.58 0.05 0.03 -0.07 -0.05 0.15 0.20 0.58 1.00 0.34 0.35 0.23 0.25 0.53 0.51 0.05 0.34 1.00 0.93 0.91 0.84 0.90 0.82 0.03 0.35 0.93 1.00 0.89 0.92 0.87 0.76 -0.07 0.23 0.91 0.89 1.00 0.94 0.81 0.73 -0.05 0.25 0.84 0.92 0.94 1.00 0.76 0.67 0.15 0.53 0.90 0.87 0.81 0.76 1.00 0.91 0.20 0.51 0.82 0.76 0.73 0.67 0.91 1.00 F341 2018 36 Suppose your Risk Aversion parameter A = 4.0. Here are the optimal weights: US Bonds -18.03% Foreign Bonds 26.61% US LargeCap Growth US LargeCap Value US SmallCap Growth Small-Cap Value Foreign Equity Emerging Markets 536.67% -204.07% -139.81% 140.81% -237.84% -4.34% F341 2018 37 Holy cow, is the what “state-of-the-art” advice gives you? Would you put 536% in large cap growth? Would you short foreign stock 238%? Large cap value 204%? What is driving these results? F341 2018 38 It seems that the optimized results are largely driven by the historical experience in average returns. But, the advice is wildly inconsistent with any equilibrium notion. F341 2018 39 A very common adjustment is to plug in market-based expected returns. Essentially, we “reverse-optimize” and find the expected returns that are consistent with the existing market weights. (Note analogy to using implied volatilities) An easy way of doing this is to simply use CAPM expected returns. (Comment on why we need 2 inputs) F341 2018 40 As of January 1, 2018, these are the relative market weights of the 8 asset classes: US Bonds 19.86% Foreign Bonds 25.97% US LargeCap Growth US LargeCap Value US SmallCap Growth Small-Cap Value 12.69% 12.46% 1.07% 1.00% F341 2018 Foreign Equity 21.23% Emerging Markets 5.72% 41 Using the market weights (keep them fixed), we construct a data series of monthly market returns. We then use the CAPM SML equation to derive expected returns: E (r ) r ( E (r ) r ) We need 2 inputs: f m f ◦ For the riskless rate, I choose the current 5 year TBill yield of 2.33% per annum. ◦ For the market risk premium, E ( r ) r , I use the 25 year historical average (for these 8 asset classes) of 4.83% per annum. ◦ Make sure you divide by 12 for monthly inputs m f F341 2018 42 US Bonds 2.75% Foreign Bonds 4.78% US LargeCap Growth US LargeCap Value US SmallCap Growth 8.73% 8.83% 9.88% SmallCap Value Foreign Equity Emerging Markets 10.60% 11.75% 9.55% These expected returns make much more sense. They are broadly consistent with relative risk. Note again that these are annualized. Use the monthly returns for optimization. F341 2018 43 Suppose your Risk Aversion parameter A = 4.0. Here are the optimal weights: US Bonds 11.70% Foreign Bonds 29.29% US LargeCap Growth US LargeCap Value US SmallCap Growth Small-Cap Value 14.08% 12.87% 0.11% 1.72% F341 2018 Foreign Equity 23.40% Emerging Markets 6.83% 44 The positions now seem reasonable. F341 2018 45 Consider the advice to an investor with risk aversion parameter A= 4.3875 . US Bonds Foreign Bonds US LargeCap Growth US LargeCap Value US SmallCap Growth 19.86% 25.97% 12.69% 12.46% 1.07% SmallCap Value 1.00% Foreign Equity 21.23% Emerging Markets 5.72% These are precisely the market weights. (Is there a simple formula for deriving this? Try to figure it out.) Easy to use “guess & check”. Don’t use Solver for this. F341 2018 46 A very common approach for quantitative asset allocation is to begin with the marketimplied expected returns. Then, you add to the model your own “views” on the relative expected returns. For example, you might be bullish on US large cap growth, and believe a 15% expected return is reasonable. Finally, you weight the market’s views and your own views, based on the degree of confidence you have in your views. F341 2018 47