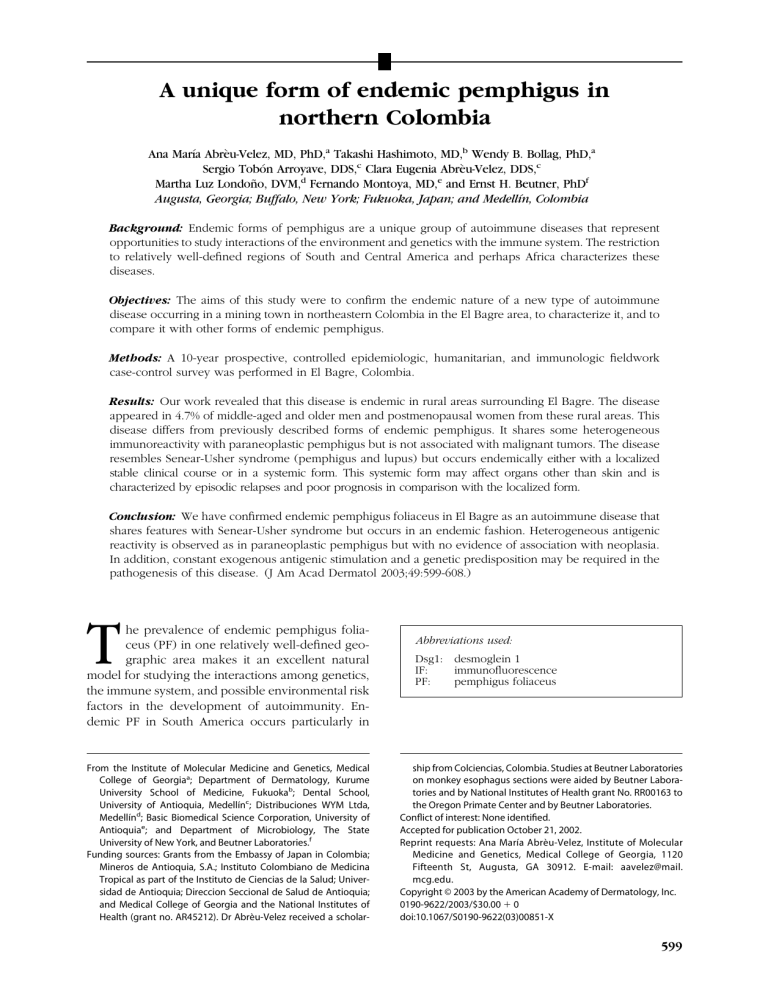

A unique form of endemic pemphigus in northern Colombia Ana Marı́a Abrèu-Velez, MD, PhD,a Takashi Hashimoto, MD,b Wendy B. Bollag, PhD,a Sergio Tobón Arroyave, DDS,c Clara Eugenia Abrèu-Velez, DDS,c Martha Luz Londoño, DVM,d Fernando Montoya, MD,e and Ernst H. Beutner, PhDf Augusta, Georgia; Buffalo, New York; Fukuoka, Japan; and Medellı́n, Colombia Background: Endemic forms of pemphigus are a unique group of autoimmune diseases that represent opportunities to study interactions of the environment and genetics with the immune system. The restriction to relatively well-defined regions of South and Central America and perhaps Africa characterizes these diseases. Objectives: The aims of this study were to confirm the endemic nature of a new type of autoimmune disease occurring in a mining town in northeastern Colombia in the El Bagre area, to characterize it, and to compare it with other forms of endemic pemphigus. Methods: A 10-year prospective, controlled epidemiologic, humanitarian, and immunologic fieldwork case-control survey was performed in El Bagre, Colombia. Results: Our work revealed that this disease is endemic in rural areas surrounding El Bagre. The disease appeared in 4.7% of middle-aged and older men and postmenopausal women from these rural areas. This disease differs from previously described forms of endemic pemphigus. It shares some heterogeneous immunoreactivity with paraneoplastic pemphigus but is not associated with malignant tumors. The disease resembles Senear-Usher syndrome (pemphigus and lupus) but occurs endemically either with a localized stable clinical course or in a systemic form. This systemic form may affect organs other than skin and is characterized by episodic relapses and poor prognosis in comparison with the localized form. Conclusion: We have confirmed endemic pemphigus foliaceus in El Bagre as an autoimmune disease that shares features with Senear-Usher syndrome but occurs in an endemic fashion. Heterogeneous antigenic reactivity is observed as in paraneoplastic pemphigus but with no evidence of association with neoplasia. In addition, constant exogenous antigenic stimulation and a genetic predisposition may be required in the pathogenesis of this disease. (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:599-608.) T he prevalence of endemic pemphigus foliaceus (PF) in one relatively well-defined geographic area makes it an excellent natural model for studying the interactions among genetics, the immune system, and possible environmental risk factors in the development of autoimmunity. Endemic PF in South America occurs particularly in From the Institute of Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Medical College of Georgiaa; Department of Dermatology, Kurume University School of Medicine, Fukuokab; Dental School, University of Antioquia, Medellı́nc; Distribuciones WYM Ltda, Medellı́nd; Basic Biomedical Science Corporation, University of Antioquiae; and Department of Microbiology, The State University of New York, and Beutner Laboratories.f Funding sources: Grants from the Embassy of Japan in Colombia; Mineros de Antioquia, S.A.; Instituto Colombiano de Medicina Tropical as part of the Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud; Universidad de Antioquia; Direccion Seccional de Salud de Antioquia; and Medical College of Georgia and the National Institutes of Health (grant no. AR45212). Dr Abrèu-Velez received a scholar- Abbreviations used: Dsg1: desmoglein 1 IF: immunofluorescence PF: pemphigus foliaceus ship from Colciencias, Colombia. Studies at Beutner Laboratories on monkey esophagus sections were aided by Beutner Laboratories and by National Institutes of Health grant No. RR00163 to the Oregon Primate Center and by Beutner Laboratories. Conflict of interest: None identified. Accepted for publication October 21, 2002. Reprint requests: Ana Marı́a Abrèu-Velez, Institute of Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Medical College of Georgia, 1120 Fifteenth St, Augusta, GA 30912. E-mail: aavelez@mail. mcg.edu. Copyright © 2003 by the American Academy of Dermatology, Inc. 0190-9622/2003/$30.00 ⫹ 0 doi:10.1067/S0190-9622(03)00851-X 599 600 Abrèu-Velez et al Brazil, where the disease is known as fogo selvagem.1-12 Endemic PF differs from sporadic PF (Cazanave’s PF) in its geographic distribution, high familial incidence, and age of onset (youth in fogo selvagem versus adults in the sporadic form of the disease).1-12 In the early twentieth century, more than 15,000 fogo selvagem cases were reported in Brazil, with a remarkably high incidence in rural areas. The disease occurs often in children, young people aged 14 to 16 years, and young adults, with the highest incidence (50%) in the 20- to 30-year-old age group, and affects both sexes equally.1-12 Most patients are poor, inhabit rural or suburban areas, and work as homemakers, farmers, or lumberjacks.1-10 In Brazil, fogo selvagem has disappeared in most previous endemic areas, and the total number of such cases has notably decreased. Recently, in a report of a new focus in Brazil, fogo selvagem patients had epidemiologic features slightly different from the original descriptions.12,13 A recent study of fogo selvagem in São Paulo revealed that 60.4% of endemic PF patients were female, 79.2% were white, their ages ranged from 7 to 82 years old, and large percentages were in their teens (29%) and living in rural areas (46.9%).14,15 In 1993, another possible focus of endemic PF in Tunisia, North Africa, affected predominantly young women, had no familial component, and had clinical features resembling herpetiform pemphigus. However, no fieldwork confirmed the endemic nature of this PF focus.16,17 The existence of another possible focus of endemic PF, this time in the South Amazonian and Orinoquian rain forest of Colombia, was reported to have features like those in the original reports of fogo selvagem.18 In addition, the existence of another probable focus of endemic PF was described in a retrospective 1976-86 study of 21 cases of endemic PF diagnosed in a reference hospital in Colombia.19,20 Since no dermatologist visited this possible focus and no field study was performed, we visited the area to better characterize the disease, to compare this new focus with other described endemic PF foci, and to confirm its endemic nature. MATERIALS AND METHODS Subjects For 10 years (1992-2001), an active search was undertaken to detect endemic PF cases in El Bagre, a rural village in northeastern Colombia, and the area surrounding this village, at the northern end of Colombia’s Central Cordillera, 284 km north of J AM ACAD DERMATOL OCTOBER 2003 Medellı́n (Fig 1).21,22 The area around El Bagre is characterized by fighting among guerrilla, paramilitary, and military forces in disputes over land, power, money, and narcotics. The population is 41% American Indian and white (mestizo), 15% white, 14% American Indian and black (zambo), 3% white and black (mulatto), and 1% American Indian.21,22 We evaluated approximately 6000 people from the area, examining endemic PF patients, as well as control volunteers who matched the patients in terms of age, sex, residence, and work activities. Controls from the endemic area included people with or without other dermatoses (Table I). Laboratory studies Skin biopsy specimens were taken from endemic PF–like lesions on each patient and examined histopathologically. Direct immunofluorescence (IF) of the specimens was performed as previously described.23 Sera from patients were also examined for the presence of anti– cell surface antibodies by means of indirect IF with monkey esophagus and human foreskin sections used as substrates.24 Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot data are detailed in a separate report.25 Statistical evaluation Previously codified original data, tabulated in the Epi-Info program for distribution frequencies and associations, were graphed with the Harvard Graphics package (Table I). So that we could identify potential factors associated with disease development, patients and controls also completed a questionnaire. Data were evaluated as blind studies by two epidemiologists. RESULTS Clinical findings The clinical findings are described in Table I. Patients showed keratotic follicular skin lesions resembling discoid lupus erythematosus, or the abortive form of fogo selvagem, similar to Senear-Usher syndrome (Fig 2). The most typical lesions found in our patients were hyperkeratotic plaques on the face, chest, and back, referred to as acanthoma. All active cases also showed conjunctivitis, which was diagnosed by two ophthalmologists as actinic in origin (Table I). As in fogo selvagem, oral, nasal, pharyngeal, genital, and anal mucosae were not affected. Also as in fogo selvagem, the soles and palms were not affected by lesions. However, hyperkeratosis was observed on the soles and palms, and in patients with more than 70% of their skin affected, these areas showed a pruned appearance. We found that many persons progressed through various clinical stages, whereas a few had a stable J AM ACAD DERMATOL VOLUME 49, NUMBER 4 Abrèu-Velez et al 601 Fig 1. Geographic and demographic distribution of the El Bagre municipality in Colombia. A, Map of Colombia, with the state of Antioquia outlined and shaded. The El Bagre area is indicated by darker shading and a star. B, Larger map of Antioquia with a star showing El Bagre and surrounding municipalities of El Bajo Cauca, a political and geographic region of Antioquia that has 137,023 inhabitants, of whom 90,832 live in urban areas and 46,191 in rural areas. El Bajo Cauca includes Cáceres, Tarazá, Caucasia, Zaragoza, Nechı́, Arboletes, San Juan de Urabá, and El Bagre. clinical course. We were unable to utilize chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine and thalidomide, because warfare in the area prohibits their use. Our treatment strategy involved the use of oral or topical steroids (we prefer topical ones), antihistamines, sun-protective clothing, and sun block and dietary interventions. Histopathologic findings Histopathologically, acantholysis in granular layers (a typical feature of PF) was seen only in new, active, or exacerbated skin lesions (Fig 3). In total, 42.3% of skin biopsies showed the changes typical of PF. Follicular hyperkeratosis with some dyskeratosis appeared in the granular layer of old lesions. Chronic dermatitis–like changes with scleroderma-like alterations (23%), pustule formation (15.4%), lupuslike features mixed with pemphigus-like changes (29%), psoriasiform changes (7.7%), and lesions resembling polymorphic light eruptions also appeared. In addition, skin biopsies in about one fourth of the patients showed liquefaction or degeneration of the basement membrane zone, correlating with the clinical lupuslike appearance seen in 29% of cases. Laboratory findings By direct IF, all the skin biopsy specimens obtained from active endemic PF patients revealed IgG deposition on keratinocyte cell surfaces (Fig 4, A). Also, deposition of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 on the basement membrane zone gave a positive lupus band test by direct IF in 40% of the endemic PF cases (Table II and Fig 4, B). Such positive lupus bands rarely occur in Brazilian fogo selvagem. In addition, the presence of the lupus band correlated in 100% of the cases with clinical signs of Senear-Usher syndrome and histopathologic findings of lupuslike features mixed with pemphigus-like changes. In approximately two thirds of these patients, basement membrane zone liquefaction was also noted. Tests of 30 serum samples from El Bagre endemic PF patients and controls for antinuclear antibody (ANA) with enzymelinked immunosorbent assay kits (Incstar Co, Stillwater, Minn) revealed ANA in one endemic PF and one control serum. Indirect IF for IgG4 antibodies revealed prominent intercellular staining (Table II). These results, as well as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method for desmoglein 1 602 Abrèu-Velez et al J AM ACAD DERMATOL OCTOBER 2003 Table I. Epidemiologic differences between the controls from the endemic area and endemic PF patients, matched by age, sex, and living conditions. Subject characteristics Sex Male Female Presence of same disease in siblings Dermatologic diagnosis Controls (N ⴝ 130)* Statistical ‡ difference P ⬍ .0001 85% ⬎6 h/d and including the highest radiation exposure (10 AM–2 PM). P ⬍ .05 P ⬍ .0001 Depression (35%) All cases that showed high clinical activity Depression (80%) Fatigue (30%) Arthralgia, mainly at knee, ankles, and vertebral joints (30%) Fatigue (100%) Arthralgia, mainly at knee, ankles, and vertebral joints (90%) Psoriasis (2%) Xerotic eczema (2%) Impetigo (2%) Eccrine hydrocystoma (1%) Basal cell skin cancer (3%) Presence of actinic conjunctivitis Presence of systemic symptoms † 124 (95%) 6 (5%) (all postmenopausal) 33% of patients affected by endemic PF have siblings affected by endemic PF disease. Clinical form of pemphigus (according to Viera’s clinical classification for fogo † selvagem ) Bullous exfoliative or hyperkeratotic generalized forms (10%) Localized form (18%) Prurigoid-like form (16%) Clinically inactive (6%) Senear-Usher–like form (50%)§ Criteria, as described in the text, met for diagnosis of endemic text, met for diagnosis of endemic PF (80%) 124 (95%) 6 (5%) 10% of patients affected by atopic dermatitis have siblings affected by atopic dermatitis. Vitiligo (7%) Atopic dermatitis (4%) Sun exposure (⬍3, 3–6, and ⬎6 h) Endemic PF patients (N ⴝ 130) Lichen planus (6%) Postphlebitic syndrome (4%) Cutaneous amyloidosis (1%) No apparent dermatologic diseases (70%) 50% ⬎6 h/d and including the highest radiation exposure (10 AM to 2 PM) None detected P ⬍ .0001 P ⬍ .0001 P ⬍ .0001 *The control group and the endemic PF (pemphigus Abreu-Manu) group 25 in El Bagre were matched by following a Gaussian distribution. † From Viera JP. [Different aspects of Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus]. São Paulo: Empresa Grafica da Revista dos Tribunais; 1948. ‡ The Wilcoxon test was used to determine whether significant differences existed between the two values in each row; illustrated are the differences. The data were analyzed with Graph Pad Instant Software (San Diego, Calif) and Epi-info 2000 software (Public Health Foundation, Washington, DC). The following factors examined were not discriminating: history of malarial or gastrointestinal infections or sexually transmitted diseases, dengue, or tuberculosis; cohabitation with domestic animals; living, working, and resting distance to riverbeds; tobacco, marijuana, or liquor habits; exposure to agricultural and jungle vegetation; exposure to rodents, mosquitoes, and snakes during rest or work hours; basic diet; and percentage of skin compromised (according to Lund and Browder skin burn surface scale). § The hyperpigmented form was not considered because of intrinsic racial characteristics in each individual. (Dsg1) (RhiGene, Chicago, Ill), indicated that Dsg1 is the major autoantigen in endemic PF from El Bagre, as it is in Brazilian endemic PF. Most sera from El Bagre endemic PF patients also reacted with several other protein bands at immunoblot and immunoprecipitation analyses.26,27 These findings are now under investigation.28 Epidemiologic and statistical analysis During our 10-year surveillance with active searching, we found 130 patients with endemic PF in the area surrounding El Bagre. All cases of the dis- ease started in the rural area around El Bagre, in the municipality of El Bagre (90%), or in the neighboring rural areas of the bordering Zaragosa municipality (10%) (P ⬍ .0001). The majority of endemic PF patients were men (95.4%) in their middle forties or older, with a mean age of 50 years; the remainder (6/130, or 4.6%) were postmenopausal women. Ninety-eight percent were illiterate and poor and performed outdoor activities such as mining, farming, or forestry. All people living in the rural area lacked sewage and water systems, as in most rural areas J AM ACAD DERMATOL VOLUME 49, NUMBER 4 Abrèu-Velez et al 603 Fig 2. Clinical features. A, Numerous exfoliative skin lesions and pustules are seen. B, Lesions are present in the armpits. C, A common clinical trait of people affected by Colombian endemic PF resembles that of integumentary lupus: a butterfly pattern over malar regions with patchy hyperpigmented plaques. D, Hyperkeratotic plaques on interscapular areas are present. These plaques predominate on sagittal areas of seborrheic zones. of El Bagre; however, both patients and controls have good personal and home hygiene. Table I shows an epidemiologic comparison among endemic PF patients and controls. Table II compares different groups of endemic pemphigus. The prevalence of 130 endemic PF cases among the rural population of 5626 is 2.3%. However, since 2586 (46% of the rural population) are at risk (men 604 Abrèu-Velez et al Fig 3. Light microscopy. A, Histologic study of a papulosquamous lesion reveals subcorneal and intraepidermal acantholysis with epidermal acanthosis and papillomatosis. B, Histologic study reveals psoriasiform epidermal acanthosis with subcorneal acantholysis. (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: A, ⫻4; B, ⫻10). older than 18 years and postmenopausal women), the incidence of this disease in the group at risk is closer to 5%, and our data confirm the endemicity of this disease in the rural area surrounding El Bagre. The prevalence of endemic PF in women of childbearing years was 0.23% (similar to that of the sporadic form). The prevalence of endemic PF over 10 years has been stable (about 3 to 10 new cases per year) with similar mortality. This disease can be catalogued as chronic, since two thirds of patients had suffered from the disease for 1 to 30 years. In the rural areas surrounding El Bagre, Indians, who make up about 1% of the total population, had 10.8% of the cases identified, indicating that the disease is prevalent among this ethnic group compared with other races (P ⬍ .0001). Severe complications of El Bagre endemic PF Presently, about 30 patients have died. The causes of death we detected included stroke; peri- J AM ACAD DERMATOL OCTOBER 2003 Fig 4. Direct immunofluorescence. A, IgG deposits show typical intercellular staining between keratinocytes in all cases. When using mouse antihuman IgG, IgM, or IgA, complex immunofluorescence was observed, consisting of staining of the basal membrane zone and basal keratinocytes, as well as some intracellular staining. B, C3 complement deposits in the basement membrane area resemble a lupuslike band. tonitis of unknown origin; exacerbation of endemic PF; tuberculosis; renal, liver, and lung failure of unknown cause; and chickenpox in 3 patients. In addition, some hospitalized patients had proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, generalized edema, hematuria, leukocyturia, and frank nephrotic syndrome indicating possible renal failure. Indeed, chronic kidney failure with decreased creatinine clearance was diagnosed in two patients with a lupus band in the skin and with facial eruptions in a butterfly distribution over the malar areas and bridge of the nose. An abrupt death syndrome without apparent cause was also reported by the relatives of some patients. Diagnostic autopsies were performed only in 2 patients who died as the result of complications from chickenpox. The autopsies in these 2 cases showed a severe generalized endotheliitis in most organs. In our experience, the disease activity of chickenpox (herpesvirus) and tuberculosis is severe in patients affected by endemic PF. Such patients show low tolerance to these diseases as is observed in most Indians. When the patients’ health declines to a state characteristic of that occurring in sepsis, Abrèu-Velez et al 605 J AM ACAD DERMATOL VOLUME 49, NUMBER 4 Table II. Clinical, epidemiologic, and immunologic features in people affected by different types of endemic PF Patient characteristics Clinical findings Age ranges Ethnic heritage Sex Racial groups Occupation Land use Environmental and geological conditions Presence of conjunctivitis* Fogo selvagem (N > 15,000)1–9,34,39 Endemic pemphigus in Tunisia (N ⴝ 22)14,15 Endemic pemphigus in El Bagre (N ⴝ 130)25 Senear-Usher syndrome (N ⴝ 366)26 Senear-Usher syndrome Senear-Usher syndrome (pemphigus (pemphigus erythematosus) in a erythematosus) in a localized form and a localized form and a generalized form with generalized form possible compromise of other organs in addition to skin 1st and 2nd decade, 21–37 y 30–70 y 0–9 y (4.6%), 10–19 y mostly 14–16 y (31.4%), 20–29 y (28.6%), 30 y or older (35.2) Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, Carthaginian, Spanish, American Spanish, Portuguese, American Indian, Roman, French, Indian, African American Indian, African Phoenician, Arab African Men (39.6%) Women of Males (95.4%) Men (45.6%) Women (60.4%) childbearing age Postmenopausal Women (54.4%) (70%) females (4.6%) Caucasian (about 50%), White Mediterranean Indian and white (40%), Caucasian (63%), Negroid (36%), mixed race (49%), (100%) Indian and black Mongoloid (1%) Mongoloid (1%) (35%), Indian (17%), White and black, or white (9%) Agriculture, forestry, Homemaking Agriculture, forestry, Agriculture, forestry, road construction, and mining road construction, homemaking homemaking Arable land (10%), Palm plantations Arable land (4%), Arable land (10%), permanent crops permanent crops permanent crops (5%), (5%), permanent (1%), permanent permanent pastures pastures (10%), forest pastures (20%), forest (10%), forest and and woodland (35%) and woodland (30%) woodland (35%) Deforestation, soil Deforestation, soil In the south, the Deforestation, soil damage from overuse damage from mining proximity to the damage from overuse activities and mercury of pesticides, air Sahara increases the of pesticides, air pollution; rich and other metal aridness of the pollution; rich deposits deposits of gold, deposits; rich depolandscape. of gold, silver, and their sits of gold, silver, and silver, and their associated metallic associated metallic their associated minerals and clays minerals and clays metallic minerals Rare† Not described In most clinically active Not described cases Cont’d on page 606 Pemphigus foliaceus typical Herpetiform (and classic pemphigus) ICS, Intercellular staining between the keratinocytes; IF, immunofluorescence. †Proenca Guimares N. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am 1974;4:291-8. ‡ “Pose of fogo selvagem” includes dwarfism; loss of hair in the scalp, eyebrow, eyelash, or pubic area; ankylosis of the large joints; demineralization of the extremities of the long bones; and endocrinologic and sympathetic alterations. * See Arneondola R. Bol Soc Bras Dermatol Sif 1944;19:329. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:1664-8. § See de Messias IT, Von Kuster LC, Santamaria J, Kajdacsy-Balla A. even cyclosporine and conventional high-dose steroids or pulses of methylprednisone are ineffective. We found many groups of genetically related patients with endemic PF: for example, siblings, uncle and nephew, and father and son. These familial cases composed about 30% of our endemic PF group. Indeed, in about 3000 families in the rural area surrounding El Bagre, 4.3% have a member in whom endemic PF has been diagnosed. Familial cases were most common among Indians, followed by the zambos; however, no siblings were affected among the white patients. We also found no en- 606 Abrèu-Velez et al J AM ACAD DERMATOL OCTOBER 2003 Table II. Cont’d Patient characteristics Fogo selvagem (N > 15,000)1–9,34,39 Presence of “Pose of ‡ fogo selvagem” In about 70% of cases in presteroid era, and just a few reported after the availability of steroids Familial cases 30% Location Rural or suburban Immunofluorescence IgG4, IgG1, C3 findings Direct IF (ICS) IgG4, IgG1, C3, and rarely, IgA and IgM Direct IF (basement membrane zone) § 5%–10% Endemic pemphigus in Tunisia (N ⴝ 22)14,15 Not described Not reported Rural IgA, IgG, C3 IgA, IgG, C3 32% (7 of 22) demic PF cases in wives, sexual partners, or cohabitants of El Bagre patients or in the group of researchers, indicating the unlikelihood of an infectious cause. The most important exacerbating factor for this disease was sun exposure or ultraviolet radiation, followed by high daily temperatures, high humidity, stress, and low protein intake. No other detectable differences in predisposing condition were detected. Clinically this pemphigus seems to affect not only the skin but also other organs, since many patients showed various systemic symptoms (Table I), such as arthritis of the major joints including wrists and ankles (80%), chronic fatigue (100%), actinic conjunctivitis (100% in the most clinically active cases), occasional episodes of syncope, dizziness, and corticonuclear cataracts, which are not the type commonly produced after long steroid treatment. In addition, an increase in the prevalence of depression and arthalgia was also observed. These clinical symptoms and some preliminary IF studies indicate autoreactivity against organs in addition to skin. In preliminary studies, we detected autoantibodies against the bladder, parietal cells of the stomach and skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, as well as intracellular organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. In addition, in about one third of the chronic cases, the skin is tight and firm, with apparent damage to the endothelium and appendages and increased dermal collagenization, resembling alterations observed in scleroderma. However, further studies are required to determine the extent of autoimmunity in these patients. In our 10 years of fieldwork, only 3 endemic PF patients have been clinically and immunologically cured. This cure occurred after the patients moved to colder mountains in the endemic area. Endemic pemphigus in El Bagre (N ⴝ 130)25 Senear-Usher syndrome (N ⴝ 366)26 Not observed, perhaps owing to the preventive use of steroids in our fieldwork studies 30% Rural IgG4 Not described IgG4, IgG1, C3, IgGM, IgGA, and lupuslike band 70% (70/100) IgG, C3 30% Rural or suburban IgG, C3 30%–40% Endemic PF in El Bagre versus known endemic pemphigus foci in Brazil and Tunisia In general, in the Brazilian and El Bagre foci, the patients were poor farmers or lumberjacks, living in rich geologic areas with extensive mining operations. Another common feature of both fogo selvagem and endemic PF in the El Bagre area is a high mestizo rate (racial mixes) of American Indians (various ethnic groups), Spanish, Portuguese, and Africans. These two types of endemic PF are distinct in the gender affected and age of onset. Fogo selvagem predominantly affects young white females under age 30, usually with 2 or 3 family members showing symptoms, and an important endocrine imbalance, that is, a generalized hypofunctioning of various endocrine glands, is characteristic. El Bagre endemic PF appears to differ from Tunisian endemic PF primarily in the profile of affected persons. Table II summarizes the similarities and the differences among the 3 forms of endemic PF. DISCUSSION Almost a century ago, thousands of cases of fogo selvagem were reported in Brazil.1-12 However, recently, only small clusters of fogo selvagem have been reported.13,14 Two settlements of people with fogo selvagem in Brazil—the Xavante reservation in Matto Grosso and the Terena reservation of Limao Verde— have mainly Indian populations and show slight epidemiologic differences, resembling more the Cazanaves PF than the fogo selvagem described a century ago.13,14 Recently, a retrospective epidemiologic study was reported from the northeastern region of the state of São Paulo in Brazil that determined the most recent prevalence of fogo selvagem.15 This study showed similar results regarding sex, race, and type of work activity but with a lower J AM ACAD DERMATOL VOLUME 49, NUMBER 4 incidence than that reported a century ago. Interestingly, in 1974, Proenca reported a high incidence of Senear-Usher syndrome occurring simultaneously in areas of fogo selvagem but again differing in age, sex, and race from our cases.26 In the El Bagre population, we observed an increased rate of vitiligo and lichen planus in comparison with other rural areas of Colombia, suggesting perhaps that an environmental factor is also increasing these diseases simultaneously with endemic PF. For example, it is known that serum selenium levels might play a role in triggering vitiligo.29 Thus exposure to such agents may represent a risk factor in this endemic disease. In general, Brazilian fogo selvagem shows extensive superficial bullae and erythematous exfoliative skin lesions on the face and trunk.1-10 Our 10-year surveillance revealed that endemic PF patients in El Bagre show similar features but also unique clinical characteristics (Table II). In addition, our study revealed that endemic pemphigus in El Bagre is epidemiologically and immunologically distinct from other known types of endemic pemphigus, such as fogo selvagem and Tunisia endemic PF, although the endemicity of the Tunisia type has not been clearly confirmed.16,17 The endemic PF patients in El Bagre presented unique features in age of onset, gender, work activities, and the presence of autoantigens in addition to Dsg1, as previously reported.25 These additional autoantibodies may be responsible for another feature of endemic PF, the hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. This hyperkeratosis is similar to the striated form of palmoplantar keratoderma, which results from mutations in desmoplakin, keratin 1, or Dsg1.30-32 Thus, we speculate that autoantibodies to Dsg1, desmoplakin, or keratin 1 induce this feature of the disease. More than 40% of endemic PF patients in El Bagre showed clinical features resembling those of SenearUsher syndrome, such as a high degree of photosensitivity like that observed by Deschamps and colleagues in Senear-Usher syndrome.33 Clinical and immunologic studies revealed some additional similarities between our endemic PF patients and those with Senear-Usher syndrome.34-38 We found a lupus band–like deposition of immunoglobulins and complement at the basal membrane zone by means of direct IF in about 40% of El Bagre endemic PF patients.34-38 Our failure to find elevated ANA in a small sampling of these patients is consistent with the findings of Chorzelski, Jablonska, and Blaszczyk36 and our laboratories (unpublished data, 1998). Most cases of El Bagre endemic PF, or pemphigus Abreu-Manu,25 have the following clinical features of the disease: (1) hyperpigmented plaques and macules mainly on the face and trunk, predominat- Abrèu-Velez et al 607 ing in the middle of the chest; (2) an erythematous butterfly-like macular lesion with fine scaling and erosions on the face; (3) pruriginous or hyperkeratotic patches with crusting mainly on the presternal and interscapular seborrheic regions and armpits; (4) occasional scarring and scabbing of the scalp, resembling a false tinea amiantacea; (5) hyperpigmentation of previous lesions (seen mostly in people showing clinical control); (6) the presence of pustules around scaling lesions; and (7) an actinic conjunctivitis–like condition. This last appears mainly in cases with high clinical and immunologic activity. Histopathologic changes in lesions of El Bagre endemic PF most resemble those seen in nonendemic PF. Cases that fulfilled most or all of the above clinical criteria and produced immunopathologic findings consistent with pemphigus were diagnosed as El Bagre endemic PF. To determine whether these patients have a systemic compromising condition, further studies are warranted. We acknowledge Stella Prada de C, MD, Walter Leon Herrera, MD, Maria Mercedes Yepes, MD, Juan Guillermo Maldonado, MD, Jorge Botero, MD, Edinson Villa, Fredy Vélez, MD, Juan Esteban Arroyave, MD, Alex Pabón, MD, Armando Muñoz, MD, Andres Jaramillo, PhD, Doris Ruiz, and all co-workers that participated in the visits to El Bagre for their contribution to this research and humanitarian program, as well as all those who donated goods for the patients. We also appreciate those who assisted the endemic PF patients at the Hospital Universitario San Vicente de Paul in Medellı́n. We extend our thanks to the El Bagre community, to Hospital Nuestra Señora de El Bagre, and to the Major Office and Health Jurisdiction in El Bagre. We also thank Darius Mehregan, MD, of Pinkus Laboratories for the study of skin biopsy specimens and for the micrographs used in this study. Special thanks go to Marcos Restrepo, MD, at ICMT for support; to Richard Plunkett, MD, and Janet Zilliox of Beutner Laboratories for testing specimens of endemic PF cases and for reading and commenting on this manuscript; and to Dawn Martin for finalizing the manuscript. This article represents a portion of the PhD thesis of Ana Marı́a Abréu Velez, who received a scholarship from Colciencias, Colombia, administered by the Latin American Scholarship Program of American Universities (USA). REFERENCES 1. Silva F. Contribucao o estudo ou penfigo foliaceo [Contributions for the study of pemphigus foliaceus]. Bras Med 1938;87:1-7. 2. Viera JP. Consirecoes sobre o penfigo foliaceo no Brasil. Sao Paulo [Different aspects of Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus]. Sao Paulo: Empresa Grafica da Revista dos Tribunais; 1948. p. 220. 3. Proenca NG, Ribeira AG. Aspectus epidemiologicos do penfigo foliaceo no Brazil [Epidemiological aspects of pemphigus foliaceus in Brazil]. Rev Assoc Med Bras 1976;22:281-4. 4. Azulay RD. Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus. Int J Dermatol 1982; 21:121-4. 5. Castro RM, Proenca NG. Semelhancas e diferencas entre o fogo selvagem e o penfigo foliaceo de Cazanave [Similarities and dif- 608 Abrèu-Velez et al 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. ferences between South American pemphigus foliaceus and Cazanaves pemphigus foliaceus]. An Bras Dermatol 1983;53:137-9. Aranja Campos J. Penfigo foliaceo: aspectos clinicos e epidemiologicos Sao Paulo [Fogo selvagem: clinical and epidemiological aspects of fogo selvagem]. Comp Melhoramentos 1942. Minelli L, Bostelman CR, Minelli HJ. Penfigo e penfigoides. Casuistica de 194 casos internados no Hospital Sao Roque (Parana) [Pemphigus and pemphigoids. Analysis of 194 hospitalized patients]. An Bras Dermatol 1990;65:67-9. Castro RM, Roscoe JT, Sampaio SAP. Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus. Clin Dermatol 1983;1:22-41. Pupo JdA. Aspectos originais do penfigo foliaceo no Brasil [Original aspects for pemphigus foliaceus in Brazil]. An Bras Dermatol 1971;46:53-60. Brown MV. Fogo selvagem (pemphigus foliaceus). Review of the Brazilian literature. Arch Dermatol Syph 1954;69:589-99. Rezende ST. Penfigo foliaceo [Pemphigus foliaceus]. Rev Bras Med 1967;24:61-2. Friedman H, Campbell I, Rocha-Alvarez R, Ferrari I, Coimbra CE, Moraes JR, et al. Endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) in native Americans from Brazil. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32: 949-56. Hans-Filho G, dos Santos V, Katayama JH, Aoki V, Rivitti EA, Sampaio SA, et al. An active focus of high prevalence of fogo selvagem on an Amerindian reservation in Brazil. Cooperative Group on Fogo Selvagem Research. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:68-75. Clarisse Z, Campbell I, Ferrerira AG. Endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem). Int J Dermatol 2000;39:812-4. Do Valle Chiossi MP, F. Roselino AM. Endemic pemphigus (“fogo selvagem”): a series from the Northeastern region of the State of Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1973-1998. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2001; 34:59-62. Morini JP, Jomaa B, Gorgi Y, Saguem MH, Nouira R, Roujeau JC, et al. An endemic pemphigus foliaceus focus in the Sousse area of Tunisia. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:69-73. Bastuji-Garin S, Souissi R, Blum L, Turki H, Nouira R, Jomaa B, et al. Comparative epidemiology of pemphigus in Tunisia and France: unusual incidence of pemphigus foliaceus in young Tunisian woman. J Invest Dermatol 1995;104:302-5. Rodriguez G, Sarmiento L, Silva A. Penfigo foliaceo en indigenas colombianos [Pemphigus foliaceus in Colombian Indian tribes]. Rev Soc Col Dermatol 1993;3:91-4. Yepes A. Brote de penfigo foliaceo en el municipio de El Bagre [A focus of endemic pemphigus in El Bagre municipality]. Bol Epidemiol Antioquia 1983;2:87. Robledo MA, Prada S, Jaramillo D, Leon W. South American pemphigus foliaceus: study of an epidemic in El Bagre and Nechı́, Colombia. 1982 to 1986. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:737-44. Angulo Mira G. Monografia de El Bagre: 50 barras de oro [Monograph of El Bagre: 50 gold bars]. In: Ciudades de Antioquia [Antioquia’s cities]. 1985. p.17-111. Pulido H, Amezquita H, Calle A. Estudio del impacto ambiental y minerı́a aurı́fera en el Bajo Cauca y Nordeste Antioqua. Volumen 2, Contaminación acuática, caracterı́sticas hidraulicas, análisis de la información [Study of the environmental effects of the mining industry in the El Bajo Cauca and northeast Antioquia. Vol 2. Aquatic pollution, hydraulic features, and information analysis]. Medellı́n, Editorial Universidad de Antioquia; 1989. Beutner EH, Prigenzy LS, Hale W, Leme CA. Immunofluorescence studies of autoantibodies to intercellular areas of epithelia in Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1968;127: 81-6. J AM ACAD DERMATOL OCTOBER 2003 24. Gammon WR, Briggaman RA, Inman AO III, Queen LL, Wheeler CE. Differentiating anti-lamina lucida and anti-sub-lamina densa anti-BMZ antibodies by direct immunofluorescence in 1.0 M sodium chloride separated skin. J Invest Dermatol 1984;82: 139. 25. Abrèu-Velez AM, Beutner EH, Montoya F, Bollag WB, Hashimoto T. Analyses of autoantigens in a new form of endemic pemphigus foliaceus in Colombia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:609-14. 26. Abreu AM, Yepes MM, León W. Pemphigus Abreu-Manu. A lost link in skin autoimmunity in endemic fashion (abstract). J Invest Dermatol 2000;114:846. 27. Proenca Guimares N. Pemphigus erythematosus (syndrome de Senear & Usher): revisao de 388 doentes [Pemphigus erythematosus (Senear-Usher syndrome): review of 366 cases]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am 1974;4:291-8. 28. Hisamatsu Y, Abrèu-Velez AM, Amagai M, Ogawa MM, Kanzaki T, Hashimoto T. Comparative study of autoantigen profiles between Colombian and Brazilian types of endemic pemphigus foliaceus by various biochemical and molecular biological techniques. J Dermatol Sci 2003;32:33-41. 29. Beazley WD, Gaze D, Panske A, Panzig E, Schallreuter KU. Serum selenium levels and blood glutathione peroxidase activities in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:301-3. 30. Hunt DM, Rickman L, Whittock NV, Eady RA, Simrack D, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, et al. Spectrum of dominant mutations in the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein 1, causing the skin disease striate palmoplantar keratoderma. Eur J Hum Genet 2001;3:197203. 31. Whittock NV, Smith FJ, Wan H, Mallipeddi R, Griffiths WA, Dopping-Hepenstal P, et al. Frameshift mutation in the V2 domain of human keratin 1 results in striate palmoplantar keratoderma. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:838-44. 32. Whittock NV, Ashton GH, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Gratian MJ, Keane FM, Eady RA, et al. Striate palmoplantar keratoderma resulting from desmoplakin haploinsufficiency. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:940-6. 33. Deschamps P, Pedailles S, Michel M, Leroy D. Photo-induction of lesions in a patient with pemphigus erythematosus. Photodermatol 1984;1:38-41. 34. Castro RM, Augusto DAF, Rivitti EA. Sindrome de Senear-Usher e Fogo selvagem (penfigo foliaceo endemico) [Senear-Usher syndrome and endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem)]. An Bras Dermatol 1988;63(suppl 1):264-5. 35. Viera JP. Penfigo foliaceo e sindrome de Senear-Usher [Pemphigus foliaceus and Senear-Usher syndrome]. Sao Paulo: Empresa Grafica da Revista dos Tribunais; 1942. 36. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszczyk M. Immunopathologic investigations in Senear-Usher syndrome (coexistence of pemphigus and lupus erythematosus). Br J Dermatol 1968;80:211-5. 37. Perry HO, Brunsting LA. Pemphigus foliaceus: further observations. Arch Dermatol 1987;26:571-7. 38. Maize JC, Green D, Provost TT. Pemphigus foliaceus: a case with serologic features of Senear-Usher syndrome and other autoimmune abnormalities. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;7:736-41. 39. Arneondola R. Lesoes oculars do penfigo foliaceo (fogo selvagem) [Ocular lesions on pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem)]. Bol Soc Bras Dermatol Sif 1944;19:329. 40. Lever WF. Pemphigus and pemphigoid. 3rd ed. Springfield (IL): Charles C Thomas Publishers; 1965. 41. de Messias IT, Von Kuster LC, Santamaria J, Kajdacsy-Balla A. Complement and antibody deposition in Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus and correlation of disease activity with circulating antibodies. Arch Dematol 1988;124:1664-8.

![Rare two cases of EPF.1540-9740.2004.03514.x[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/025161930_1-50863f89644b49f4e0ab2775c1774ff6-300x300.png)