Acute Pharyngitis/Tonsillitis Diagnosis & Treatment Study

advertisement

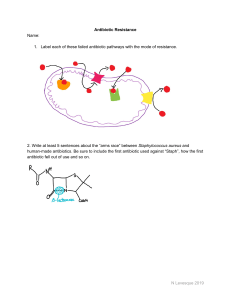

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2016; 20: 4950-4954 Diagnosis and treatment of acute pharyngitis/tonsillitis: a preliminary observational study in General Medicine F. DI MUZIO, M. BARUCCO, F. GUERRIERO Azienda Sanitaria Locale Roma 4, Rome, Italy Abstract. – OBJECTIVE: According to recent observations, the insufficiently targeted use of antibiotics is creating increasingly resistant bacterial strains. In this context, it seems increasingly clear the need to resort to extreme and prudent rationalization of antibiotic therapy, especially by the physicians working in primary care units. In clinical practice, actually the general practitioner often treats multiple diseases without having the proper equipment. In particular, the use of a dedicated, easy to use diagnostic test would be one more weapon for the correct diagnosis and treatment of acute pharyngo-tonsillitis. The disease is a condition frequently encountered in clinical practice but its optimal management remains a controversial topic. In this context, the observational study is intended to demonstrate the usefulness of the rapid test (RAD: Rapid antigen detection) against group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) in everyday clinical practice to identify individuals with acute streptococcal pharyngo-tonsillitis needing antibiotic therapy and to pursue the following objectives: (1) Getting the answer to an unmet medical need; (2) Promoting the appropriateness of the use of antibiotics; (3) Provide a means of containment in pharmaceutical spending. PATIENTS AND METHODS: 50 patients presenting sore throat associated with erythema and/or pharyngeal tonsillar exudate with or without scarlatiniform rash, fever and malaise had been subjected to perform a rapid test (RAD: Rapid antigen detection) for the search of the beta-hemolytic Streptococcus Group A (GABHS). Pharyngeal-tonsillar swabs were tested using Immunospark (relative sensitivity 97.6%, relative specificity 97.5%) according to manufacturer's instructions (runtime/reading response < 10 min). RESULTS: Of the 50 tests, 45 provided a negative response while 5 were positive for the search of the beta-hemolytic Streptococcus group A. No test result has been invalid. CONCLUSIONS: Based on the results obtained, only patients with a positive rapid test were subjected to targeted antibiotic therapy. This has resulted in a significant cost savings in 4950 pharmaceutical expenditure, without neglecting the more important and correct application of the Guidelines with performing of a clinically validated test that carries advantages for reducing the use of unnecessary and potentially harmful antibiotics and the consequent lower prevalence and incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. Key Words: Acute pharyngitis, Tonsillitis, Strep throat, Beta-hemolytic streptococcus Group A (GABHS), Rapid antigen detection test, Appropriateness use of antibiotics, Cost savings in pharmaceutical spending. Introduction Physical examination of the oropharynx is the best method for making a diagnosis of strep throat but rarely provides sufficient evidence to secure its etiology. Usually, there is a widespread hyperemia of the mucosa of the tonsils, more or less extended to the pharynx, which may be associated with other signs such as tonsillar exudate, petechiae on the soft palate or, more rarely, sores. The tonsillar exudates – whitish or frankly purulent – is often considered the only element related to the etiology of GABHS (Beta Hemolytic Streptococcus Group A). Many viruses, in particular adenovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus, may determine a comparative exudative tonsillitis, if not even more accentuated than what would be expected to be a typical GABHS. Petechiae are often associated with a streptococcal etiology, while ulcerative lesions are most often associated with viral forms. Some epidemiological data and symptoms associated with local signs of strep throat may contribute to an etiologic diagnosis1,2. Typical indications of the onset of the disease from GABHS have been: its acute onset, the absence of other Corresponding Author: Flavio Di Muzio, MD; e-mail: flaviodimuzio@yahoo.it Diagnosis and treatment of acute pharyngitis/tonsillitis acute respiratory tract illnesses in the patients’ households, the onset in late winter or early spring, the age of 3-4 years, the high fever, the sore throat, intense headache and sore laterocervical lymphadenopathy. The viral forms, however, were thought to be characterized by more modest acute systemic symptoms, with less febrile temperature, but concomitant involvement of the upper airways, the presence of family members with a similar disease, more gradual onset, usually in the summer, and elective involvement of the very first years of life. The symptoms of streptococcal pharyngo-tonsillitis and non-streptococcal varieties overlap and merge so widely that an accurate diagnosis made only on the basis of clinical signs is virtually impossible, although some have been proposed as clinical scores, such as the Mc Isaac3. Considering that the acute pharyngo-tonsillitis is one of the diseases that pediatricians and general practitioners most frequently encounter (15 million visits per year in the US alone), only a relatively small percentage of patients (20%-30% of pediatric patients, even less in adults) are actually suffering from pharyngo-tonsillitis by GABHS. With the exception of other rare bacterial infections of the pharynx (caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), antibiotic therapy is unnecessary for the acute pharyngo-tonsillitis caused by other microorganisms than GABHS even more so because most cases are caused by viruses and in particular adenovirus, influenza and parainfluenza viruses. It is extremely important to make the diagnosis accurately to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful antibiotic prescriptions4-6. At present, it is recommended to obtain a pharyngeal tonsillar swab for rapid antigen testing (RAD: Rapid antigen detection) in children or adolescents with a history, signs and/or symptoms of suspected infection by GABHS. If RAD test response is negative in subjects where there is strong evidence or suspicion of infection, a bacterial culture should be performed. In the case of a positive RAD test response, the bacterial culture is not necessary for the high reliability and specificity of the tests7-9. Bacterial culture is not necessary for the routine diagnosis of an acute pharyngitis by GABHS in consideration of the correlation of the rapid test with culture. The dosage of the anti streptococcus antibodies ASO (Anti-streptolysin O) is not recommended in the routine diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis because the presence of these antibodies reflects past infections and not ongoing infections10. Once diagnosed, patients with streptococcal pharyngo-tonsillitis should be treated with an appropriate antibiotic, in the correct dosage for the duration necessary for the eradication of GABHS from the pharynx. Baseline antibiotics for not allergic patients are penicillins, in particular amoxicillin. Treatment of streptococcal pharyngo-tonsillitis in patients allergic to penicillin should include (except cross-reactions) a first-generation cephalosporin/second generation for 10 days (5-6 days for a third-generation cephalosporin in case of dubious compliance to 10-days therapy) or clarithromycin for 10 days or azithromycin for 5 days: recommended for patients with demonstrated IgE-mediated allergy to β-lactam because of reporting macrolides resistant bacterial strains11-15. Patients and Methods Patient From November 2014 to April 2015, 50 adult patients (mean age 27.48 years) with signs and symptoms of acute pharyngo-tonsillitis were observed, in a study of general medicine. These patients, who in the absence of diagnostic tests (rapid test for GABHS), and even applying EBM (Evidence Based Medicine), may be treated with oral antibiotics (penicillin/cephalosporin or macrolide if allergic). Informed consent was signed and reported in medical records. Inclusion criteria (Figures 1 and 2): Major: sore throat associated with erythema and/or pha- Figure 1. 4951 F. Di Muzio, M. Barucco, F. Guerriero Figure 2. ryngeal/tonsillar exudate with or without scarlatiniform rash. Minor: fever, general malaise. Major criteria must always be present. Materials and Costs Rapid Test Detection Kits for Beta hemolytic Streptococcus group A of Immunospark (relative sensitivity 97.6%, relative specificity 97.5%) were used: the average price for each test being about €2.00. Total cost (figurative) €100.00. The tests were provided “free of charge” by the S.D. srl (Servizi Diagnostici Srl, Rome, Italy) and administered to patients without charge. No test result was invalid. Methodology Carrying out of pharyngeal-tonsillar swab according to manufacturer’s instructions (runtime/reading result < 10 min). Results The presence of only one band of quality control for negative response in 45 tests (90% of patients). The presence of dual band for positive response in 5 tests (10% of patients) (Figure 3). Based on the data obtained, only patients with positive response to the rapid test were subjected to antibiotic therapy. For 3 patients amoxicillin was used for 10 days; for 2 patients Ceftibuten was used for 6 days. Total cost of antibiotic therapy €65.56. 4952 Total amount: €100.00 (figurative total cost of 50 kits) + €65.56 (total cost of antibiotic therapy for positive RAD patients) = €165.56 (Figure 4). If all 50 patients were treated equally, based only on clinical evaluation (without the administering of the rapid test), with amoxicillin (not considering any allergies to penicillin and/or different treatment choices) the cost of antibiotics would be: €6.54 (two pill boxes/person) x 50 = €327.00 (Figure 4). The cost savings from only the positive patients treated correctly (rapid test + antibiotic ad hoc) and all 50 patients who were treated empirically based only on clinical data (only antibiotic without rapid test) would be as follows: €100.00 (figurative total cost 50 kit) + €65.56 (total cost of antibiotic therapy for positive RAD patients) – €327.00 (pharmaceutical expenditure of all 50 patients treated without distinction) = –€161.44 equal to 49.4% (Figure 4). If we consider the use of the currently more expensive oral antibiotic (ceftibuten) for only positive patients compared with the possible treatment of all 50 patients with the cheapest antibiotic (amoxicillin), the cost savings will be: €100.00 (figurative total cost 50 kit) + €114.85 (5 pill boxes of ceftibuten for the only positive patients) – €327.00 (All patients treated with amoxicillin) = –€112.15 equal to 34.4% (Figure 4). Discussion Besides the savings in pharmaceutical expenditure in comparison to a small charge for the cost of testing (in this case figurative total cost thanks to free delivery), we should not neglect the more important and correct application of the Guidelines. The use of the rapid antigen detection test against group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) carries advantages especially in the Figure 3. Diagnosis and treatment of acute pharyngitis/tonsillitis 49.4% Expenditure for antibiotics 34.4% Amoxicillin Only positive RAD test treated All treated with Amoxicillin vs. only positive treated All treated with Amoxicillin vs. all positive treated with Ceftibuten Figure 4. Cost savings of pharmaceutical expenditure. sense of a significant reduction in the use of unnecessary and potentially harmful antibiotics with a lower prevalence of drug-resistant forms of bacteria. This small observational study in General Medicine demonstrates that the use of rapid tests has been proven both feasible and desirable. Conclusions Rapid tests, when the Guidelines are applied, can help curb both pharmaceutical expenditure and the inappropriate use of antibiotics. –––––––––––––––––-–––– Conflict of Interest The Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. References 1) Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010; 126: e557-64. 2) CHIAPPINI E, REGOLI M, BONSIGNORI F, SOLLAI S, PARRETTI A, GALLI L, DE MARTINO M. Analysis of different recommendations from international guidelines for the management of acute pharyngitis in adults and children. Clin Ther 2011; 33: 48-58. 3) PALLA AH, KHAN RA, GILANI AH, MARRA F. Over prescription of antibiotics for adult pharyngitis is prevalent in developing countries but can be reduced using McIsaac modification of Centor scores: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med 2012; 12: 70. 4) WINDFUHR JP, TOEPFNER N, STEFFEN G, WALDFAHRER F, BERNER R. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillitis I. Diagnostics and nonsurgical management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016 Jan 11. [Epub ahead of print]. 5) S UNJOO K. Optimal diagnosis and treatment of group A streptococcal phar yngitis. Infect Chemother 2015; 47: 202-204. 6) AGARWAL M, RAGHUWANSHI SK, ASATI DP. Antibiotic use in sore throat: are we judicious? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 67: 267270. 7) GUROL Y, AKAN H, IZBIRAK G, TEKKANAT ZT, GUNDUZ TS, HAYRAN O, YILMAZ G. The sensitivity and the specifity of the rapid test in streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 74: 591-593. 8) ESCMID SORE THROAT GUIDELINE GROUP, PELUCCHI C, GRIGORYAN L, GALEONE C, ESPOSITO S, HUOVINEN P, LITTLE P, VERHEIJ T. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 Suppl 1: 1-28. 9) TAJBAKHSH S, GHARIBI S, ZANDI K, YAGHOBI R, ASAYESH G. Rapid detection of Streptococcus pyogenes in throat swab specimens by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2011; 15: 313-317. 10) CHIAPPINI E, PRINCIPI N, MANSI N, SERRA A, DE MASI S, CAMAIONI A, ESPOSITO S, FELISATI G, GALLI L, LANDI M, 4953 F. Di Muzio, M. Barucco, F. Guerriero SPECIALE AM, BONSIGNORI F, MARCHISIO P, DE MARTINO M; ITALIAN PANEL ON THE MANAGEMENT OF PHARYNGITIS IN CHILDREN. Management of acute pharyngitis in children: summary of the Italian National Institute of Health guidelines. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 14421458. 11) SHULMAN ST, BISNO AL, CLEGG HW, GERBER MA, KAPLAN EL, LEE G, MARTIN JM, VAN BENEDEN C. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55: 1279-1282. 12) THE SANFORD GUIDE TO ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY, 43th Edition, 2013. 4954 13) GAJIC I, MIJAC V, STANOJEVIC M, RANIN L, SMITRAN A, OPAVSKI N. Typing of macrolide resistant group A streptococci by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014; 18: 2960-2965. 14) PINTUCCI JP, CORNO S, GAROTTA M. Biofilms and infections of the upper respiratory tract. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010; 14: 683-690 15) W A J I M A T, C H I B A N, M O R O Z U M I M, S H O U J I M, SUNAOSHI K, SUGITA K, TAJIMA T, UBUKATA K; GAS SURVEILLANCE STUDY GROUP. Prevalence of macrolide resistance among group A streptococci isolated from pharyngo-tonsillitis. Microb Drug Resist 2014; 20: 431-435.