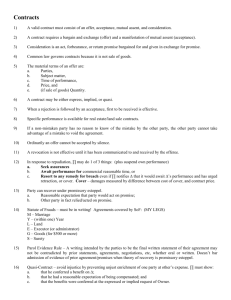

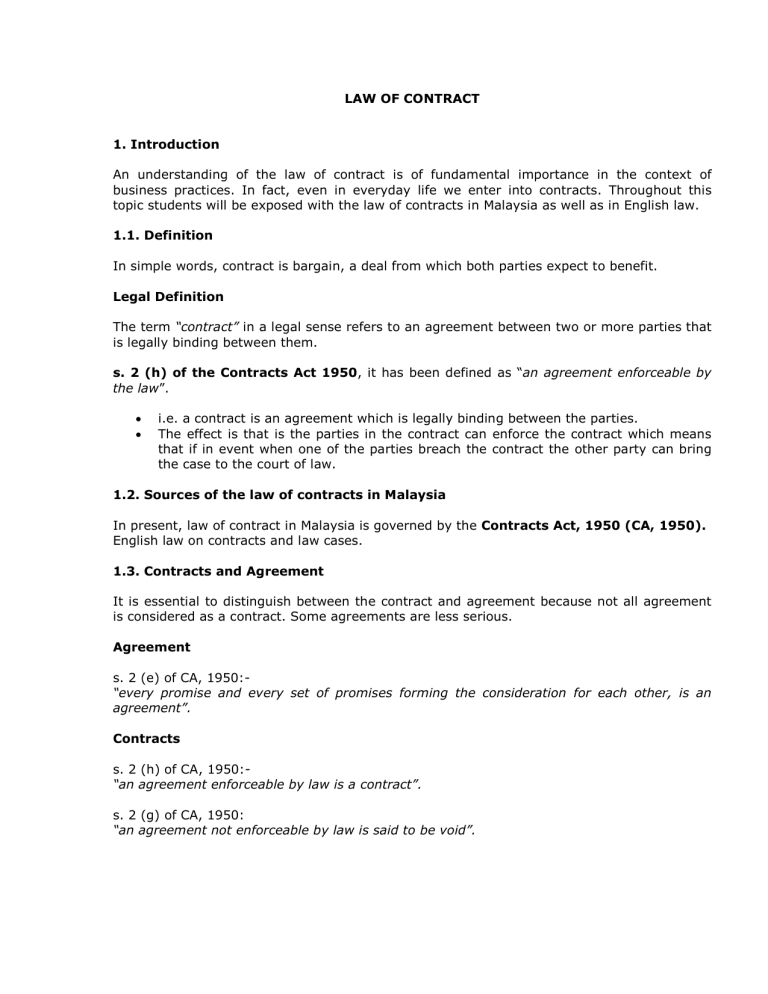

LAW OF CONTRACT 1. Introduction An understanding of the law of contract is of fundamental importance in the context of business practices. In fact, even in everyday life we enter into contracts. Throughout this topic students will be exposed with the law of contracts in Malaysia as well as in English law. 1.1. Definition In simple words, contract is bargain, a deal from which both parties expect to benefit. Legal Definition The term “contract” in a legal sense refers to an agreement between two or more parties that is legally binding between them. s. 2 (h) of the Contracts Act 1950, it has been defined as “an agreement enforceable by the law”. · · i.e. a contract is an agreement which is legally binding between the parties. The effect is that is the parties in the contract can enforce the contract which means that if in event when one of the parties breach the contract the other party can bring the case to the court of law. 1.2. Sources of the law of contracts in Malaysia In present, law of contract in Malaysia is governed by the Contracts Act, 1950 (CA, 1950). English law on contracts and law cases. 1.3. Contracts and Agreement It is essential to distinguish between the contract and agreement because not all agreement is considered as a contract. Some agreements are less serious. Agreement s. 2 (e) of CA, 1950:“every promise and every set of promises forming the consideration for each other, is an agreement”. Contracts s. 2 (h) of CA, 1950:“an agreement enforceable by law is a contract”. s. 2 (g) of CA, 1950: “an agreement not enforceable by law is said to be void”. 1.4. Basic Elements of Contract Laws Offer Acceptance Capacity Consideration Intention to create Certainty legal relation of the contract Free consent 2. OFFER/PROPOSAL 2.1. Definition Offer or better known as proposal in the CA, 1950 bears a same meaning and is one of the necessary elements in the contract. A proposal is a statement by one party that he is willing to do or abstain from doing something. s. 2 (a) of CA, 1950:“when one person signifies to another his willingness to do or to abstain from doing anything with a view to obtaining the assent of that other to the act or abstinence, he is said to make a proposal”. There are two (2) key points to be noted from this definition:(i) expression of willingness to do or not to do; and (ii) in order to get the second party’s consent of that act or abstinence. Example: X, offer to sell his car to Y – the act of X offering Y showing his willingness to sell the car to Y. X makes the offer in order to get consent (acceptance) from Y to buy the car. X as a person making the proposal is now referred as “promisor” or “offeror”. s. 2 (c) of CA, 1950:“the person making the proposal is called the “Promisor”…” An offer is not required to be in particular form. It can be written, verbal (expressed proposal) or made by action (implied proposal) 2.2. Types of Offer Offer can be either specific or general. (a) Specific offer It is referred when the offer makes to a specific person or specific group of people. (b) General offer It refers when the offer makes to people at large. Case: Carlill v. Carbollic Smoke Ball Co. Ltd [1893] 1 Q.B. 256 It was held in this case that an offer (proposal) can be made to the world because the contract will only be made with that limited portion of the public who came forward and performed the condition on the faith of the advertisement 2.3. Offer and Invitation to Treat (ITT) An offer must be distinguished from an ITT. An ITT invites people to make offers. It is not a proposal but a sort of preliminary communication which passes between the parties at the stage of negotiation and not capable of being turned into a contract. Example:Price list, a display of goods with price tags in a self-service supermarket, advertisement or an auctioneer inviting bids for a particular article. (i) Mere statements of price A statement of minimum price at which a party may be willing to sell will not amount to an offer. Case: Harvey v. Facey [1893] AC 552 Facts: The Plaintiff telegraphed to the Defendants stating: “Will you sell us Bumper Hall Pen? Telegraphed lowest cash price”. The Defendants telegraphed in reply stating: “Lowest price for Bumper Hall Pen is $900”. (2nd telegraph) The Plaintiff then telegraphed stating: “We agree to buy Bumper Hall Pen for $900 asked by you. Please send us your title deeds”. (3rd telegraph) Issue: Whether the exchange of telegraph between the parties constitute a valid Offer and Acceptance (Contract). Held: There was no contract. The 2nd telegraph was not an offer but only an indication of the minimum price if the Defendants ultimately resolved to sell. The 3rd telegraph therefore was not an acceptance. (ii) Advertisement Advertisements are normally interpreted as ITT. Case: Partridge v. Crittenden [1968]1 WLR 1204 Facts: In this case the appellant had inserted an advertisement to sell protected bird under the general heading of Classified Advertisements and the words ‘offer for sale’ were not used. He was charged with unlawfully offering for sale of wild live bird contrary to the provisions of the Protection of Birds Act 1954, and he was convicted. However the court quashed the conviction. Held: A classified advertisements in a magazine or newspaper did not amount to an offer to contract. There is no sufficient amount to contract. Case: Preston Corp. Sdn. Bhd. V. Edward Leong & Ors [1982] 2 MLJ 22 Facts: The appellant publishers asked for quotations from the respondent printers which were duly given to them. The appellants then placed printing orders based on the quote. Issue: Whether printing orders made by the appellants were an acceptance of a binding offer or merely offers in response to an invitation by the respondents. Held: The Federal Court decided that the quotations were merely a supply of information which was really an invitation to enter into a contract in response to the appellants’ inquiry. The printing orders were offers subject to acceptance by the respondents. However, advertisement may also be construed as offer. In order to determine whether an advertisement is an offer or ITT is depends on the intention of parties. Case: Carlill v. Carbollic Smoke Ball Co. Ltd [1893] 1 Q.B. 256 Facts: An advert was placed for ‘smoke ball’ to prevent influenza. The advert offered to pay ₤100 if anyone contracted influenza after using the ball. The company deposited ₤1000 with the Alliance Bank to show their sincerity in the matter. The Plaintiff bought one of the balls but contracted influenza. Held: The Plaintiff was entitled to recover ₤100. The court further held: (a) The deposit of money showed an intention to be bound, therefore an advert was offer (b) It was possible to make an offer to the world at large, which as accepted by anyone who buys a smoke ball (c) The buying and using of the smoke ball amounted to acceptance. As a conclusion: (a) Advertisement is merely an attempt induce offers or ITT. (b) It usually silence on matters which are valid to the contract. (c) It is an expression of willingness to negotiate, inviting the reader to request the services or goods prescribed. (iii) Brochure Not an offer because it is silent as to the availability of the services or goods. (iv) Booking form Not an offer from advertiser but merely as ITT. The reader may fill the form and allow the advertiser process the form. In this situation the reader is considered to make an offer to the advertiser. (v) Auction The legal position is that the auctioneer is only making an ITT. The auctioneer is merely inviting the people to present to make proposals which the auctioneer may accept or decline to accept. (vi) Display of goods in a shop Generally it does not constitute a proposal. Rule: An offer is made by a customer when he or she selects the desired goods for payment at the counter. Case: Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (PSGB) v. Boots Cash Chemist Ltd. [1953] 1 Q.B. 401 Facts: The defendants were charged under the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1933 which made it unlawful to sell certain poisons unless such sale were supervised by registered pharmacist. The case depended on whether there was a sale when a customer selected items he wished to buy and placed them in his basket. Payment was to be made at the exit where a cashier was stationed and, in every case involving drugs, a pharmacist supervised the transaction and was authorized to prevent a sale. Held: The display was only an ITT. A proposal to buy was made when the customer put the articles in the basket. Hence the contract would only be made at the cashier’s desk. As such, the shop owner had not made an unlawful sale. Case: Fisher v. Bell [1961] 1 Q.B. 394 at 399 Held: It is clear that according to the ordinary law of contract, the display of an article with a price on it in a shop window is merely an ITT. 2.4. Elements of Offer (i) Certainty of Offer A proposal must be clear, certain, definite and absolute which is completed in all terms condition and consequence and no doubt. The offer must be firm. There must be definite intention to adhere to the offer. (ii) Communication of Offer A proposal must be communicated. s. 4 (1) of CA, 1950 reads as follows: “the communication of a proposal is complete when it comes to the knowledge of the person to whom it is made”. A proposal is said to have been communicated only if the party who accepts it knew about the proposal. Case: Carlill v. Carbollic Smoke Ball Co. Ltd [1893] 1 Q.B. 256 Held: The communication of offer was completed when the offer came to the knowledge of the Plaintiff. Therefore if a party accepting a proposal is not aware about the proposal, then there is no contract. Case: R v. Clarke (1927) 40 CLR 227 Facts: The Western Australian Government offered a reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of persons responsible for the murder of 2 police officers. X and Clarke were later arrested and charged with the murders. Clarke later gave some information to the police which resulted to the arrest of another person Y. Clarke was later found not guilty. He later claimed for the reward. Held: His claim failed because although he has seen the offer, it was not present to his mind when he gave the information to the police. 2.5. Types of Proposal By virtue of s. 9 of CA, 1950, proposal can be divided into 2 (two):i) Expressed proposal – a proposal made in words (i.e. written, oral) ii) Implied proposal – a proposal which is made by other than words (i.e. by conduct) 2.5. Revocation of Proposal s. 5 (1) of CA, 1950 states as follows:“A proposal may be revoked at any time before the communication of its acceptance is complete as against the proposer, but not afterwards”. By virtue of s. 6 of CA, 1950, proposal may be withdrawn in any of the following circumstances:a) By communication of notice of revocation (s. 6 (a) of CA, 1950); b) By lapse of the time prescribed in the proposal or if no time prescribed by the lapse of a reasonable time (s. 6 (b) of CA, 1950); c) By the failure of the acceptor to fulfill a condition precedent to acceptance (s. 6 (c) of CA, 1950); and d) By the death or mental disorder of the proposer, if the fact of the proposer’s death or mental disorder comes to the knowledge of the acceptor before acceptance (s. 6 (d) of CA, 1950). 3. ACCEPTANCE 3.1. Definition Section 2 (b) of Contracts Act 1950 (CA 1950) states as follows:“When the person to whom the proposal is made signifies his assent thereto, the proposal, when accepted, becomes a promise”. Section 2 (c) of CA 1950 states as follows:“… the person accepting the proposal is called the promisee”. 3.2. Rule of Acceptance a) Elements of acceptance i. Acceptance must be absolute and unqualified s. 7(a) of CA 1950:“In order to convert a proposal into a promise the acceptance must be absolute and unqualified”. The rule is that any acceptance which is qualified by the introduction of new term may be considered as a COUNTER-OFFER and the effect of a counter-offer is treated as a rejection of the original proposal. Case: Hyde v. Wrench (1840) 3 Beav. 334 Facts: 6 June Defendant wrote to Plaintiff offered to sell his estate to Plaintiff for 1000 pounds. 8 June Plaintiff replied, he made a counter-proposal to purchase at 950 pounds. 27 June Defendant rejected Plaintiff’s offer. 29 June Plaintiff offered 1000 pounds. Defendant refuse to sell and Plaintiff sued for breach of contract. Held: No acceptance had occurred because the Plaintiff’s letter on 8 June had rejected the original proposal which could not be revived. However, this rule does not mean that further communication between the parties subsequent to the original proposal is not permissible. There is distinction between a counter-proposal and a request for further information. Case: Stevenson Jaques & Co. v. Mc Lean (1880) 5 QBD 346 Facts: On Saturday, the Defendant offered to sell iron to the Plaintiff at 40 shillings a ton, open until Monday. On Monday at 9.42 am, the Plaintiff sent a telegram asking if he could have credit terms. After receiving it Defendant sold the iron to another purchaser and at 1.25 pm sent a telegram to Plaintiff informing them about the sale. At 1.34 pm the Plaintiff sent a telegram accepting the Defendant’s original offer. Plaintiff claimed that the last telegram was an acceptance of the Defendant’s offer. Held: The court agreed with the Plaintiff’s claim and held that the Plaintiff’s first telegram was not counter-offer but only an enquiry, so a binding contract was made by the Plaintiff’s second telegram. ii) Must be made within a reasonable time S. 6 (b) of CA 1950:“A proposal is revoked by the lapse of the time prescribed in the proposal for its acceptance, or, if no time is so prescribed, by the lapse of a reasonable time, without communication of the acceptance”. What amount to the reasonable time is a question of fact. It depends on the circumstances of each case. iii) Must be expressed in some usual and reasonable manner unless the proposal prescribes the manner in which it is to be accepted. s. 7 (b) of CA 1950 When the acceptor deviates from the prescribed form the offeror must not keep silent. If he does so and fails to insist upon the prescribed manner, he is considered as having accepted the acceptance in the modified manner. iv) Must be communicated Acceptance is only effective when it has been communicated. There are two (2) rules for this particularly:- (a)Acceptance by Post (Postal Acceptance Rule) In England The communication of acceptance is complete upon posting. In Malaysia Contract Act stipulated different times when the communication of acceptance is complete. s. 4 (2) of CA 1950 states as follows:The communication of an acceptance is complete(a) as against the proposer, when it is put in a course of transmission to him, so as to be out of the power of the acceptor; and (b) as against the acceptor, when it comes to the knowledge of the proposer Illustration: X accepts Y’s proposal by a letter sent by post on 1st December, 2005.The communication of acceptance is complete:a) as against Y (proposer), when the letter is posted; and b) as against X (acceptor), when the letter is received by Y. Case: Ignatius v. Bell [1913] 2 FMLSR 115 Facts: Plaintiff sent a notice of acceptance by registered post in Klang on August 16, 1912 but it was not delivered till the evening of August 25. The letter had remained in the post office at Kuala Selangor until picked up by the defendant. Held: The option to accept was considered being exercised by the Plaintiff when the letter was posted on August 16. Principle: Acceptance is complete upon posting where the communication by post is the method contemplated by the parties. þ Why do we need to know when is communication of acceptance is complete? In order to know a valid time for parties to revoke the proposal or to accept it. (b) In case of instantaneous circumstances Example: telephone, telex and telefax or e-mail, postal rule does not apply. Rule: An acceptance made by these modes must be actually come to the knowledge of the offeror. Case: Entores Ltd. v. Miles Far East Corporation [1955] 2 Q.B. 327 Facts: An offer was sent by telex from London. An acceptance was sent by telex from Amsterdam to London. The telex service is practically an instantaneous means of communication. It enables a message to be dispatched by a teleprinter operated like a typewriter in one country and almost instantaneously received and typed in another. The Plaintiff wished to claim damages against the defendant for breach of contract and wished to start an action in London. However this it could do if the contract was made in England. Issue: The issue was when acceptance was completed and where the contract was made. Held: The court decided that the contract was made in London i.e. at the place where the acceptance was received. 3.3. Revocation of Acceptance s. 5 (2) of CA 1950 states as follows:“An acceptance may be revoked at any time before the communication of the acceptance is complete as against the acceptor, but not afterwards”. þ When is the communication of the acceptance is complete as against the acceptor? According to s. 4 (2) (b) of CA 1950 :The communication of an acceptance is complete- as against the acceptor, when it comes to the knowledge of the proposer. 3.4. Communication of Revocation The communication of revocation (proposal or acceptance) is governed by s. 4 (3) of CA 1950. The communication of a revocation is complete(a) as against the person who makes it, when it is put into a course of transmission to the person to whom it is made so as to be out of the power of the person who makes it; and (b) as against the person to whom it is made, when it comes to his knowledge. Illustration of s. 4 (3) of CA 1950 (c) A revokes his proposal by telegram The revocation is complete as against A when the telegram is sent. It is complete as against B when B receives it. (d) B revokes his acceptance by telegram B’s revocation is complete as against B when the telegram is dispatched, and as against A when it reaches him. TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING Situation A proposes, by a letter sent by post on 12.12.2004 to sell his house to B. B accepts the proposal by a letter sent by post on 13.12.2004 and A receive the letter on 15.12.2004. Decide:1. When A may revoke his proposal? 2. When B may revoke his acceptance? 4. CAPACITY 4.1. General Rule In order to enter into a valid contract the parties to the contract should be competent to the contract i.e. must have legal capacity. Who are competent to contract? (i) Who is of age of majority; and (ii) Who is of sound mind. Authorities:(i) s. 11 of CA 1950 “every person is competent to contract who is of the age of majority according to the law to which he is subject, and who is of sound mind, and is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject”. (ii) Age of Majority Act, 1971 – Age of major is 18 years old. What is the effect of contract entered by an infant? Effect of contracts made by those who are incompetent are not stipulated under the Act. In the case of Mohari Bibie v. Dharmodas Ghose [1903] 1 L.R. 30 Cal. 539 where the court held that contract made by a minor is void. In the case of Tan Hee Huan v. Teh Boon Keat [1934] 1 MLJ 96, the court held that transfer of land executed by an infant was void Thus, the general rule in Malaysia is that contracts made by infants are void and by virtue of s. 2 (g) of CA 1950, a void contract cannot be enforceable by law. Reasons:(i) As a protection to the minor against the consequences of its own action. (ii) Minor is presumed lack of judgment in such matter. 4.2. Exceptions: (i) Contract of necessaries s. 69 of CA, 1950 Necessaries are things which are essential to the existence and reasonable comfort of the infant, i.e. food and clothes. Test: Depends on the condition of the minor’s life. They also include necessaries supplied to anyone he is legally bound to support such as his wife or child. The minor is not personally liable – he must pay only if he has property to do so, such as bicycle or motorcycle. Minor is not bound by contracts for goods which are not necessaries. The burden for proving that goods are necessaries lies on the seller. Case: Nash v. Inman [1908] 2 KB 1 Facts: Inman, an undergraduate at Cambridge ordered clothes from a tailor worth £22. Held: Action by Plaintiff failed because tailor failed to adduce any evidence to show that clothes suitable for infant’s station in life. Case: Govt. of Malaysia v. Gurcharan Singh [1971] 1 MLJ 211 Held: Education was held to be ‘necessaries’. (ii) Contract of Scholarship s. 4 (a) of the Contracts (Amendment) Act 1976 provides that no scholarship agreements shall be invalidated on the ground that the scholar entering into such agreement is not of the age of majority. This provision however confines to scholarship agreements with governmental agencies. The amendment does not affect the general law relating to contracts including scholarship agreements between minors and private organizations. (iii) Contract of Insurance s. 153 (1) and (2) of the Insurance Act 1996 states that:(a) an infant over the age of 10 may enter into a contract of insurance. (b) If below 16, can do so with the written consent of his parent/ guardian. (iv) Contract of Service / Apprenticeship There are 2 legislations enabling a minor to enter into contract of service particularly:(a) Employment Act 1955; and (b) Children and Young Persons (Employment) Act 1966. Rule: Though the child or young person may sue or defend under such contracts of service, no damages or indemnity can be recovered from him for breach. 5. CONSIDERATION Definition A benefit to one party or a detriment to the other – OR the element of exchange in a contract – OR the price paid for a promise. THREE (3) Types of consideration 1. Executory – a promise to do something in the future. Example: S agrees to sell B a house and B promises to pay RM200,000. Here B’s promise to pay the amount of RM200,000 is the consideration for S’s promise to sell the house and S’s promise to sell the house is the consideration for B’s promise to pay RM200,000. 2. Executed – when a promise is made in return for the performance of an act. Example: A offers RM200 to anyone who finds and returns his digital camera which he has earlier lost. B finds and returns his digital camera in response to the offer. B’s consideration for A’s promise is executed, and only A’s liability remains outstanding. 3. Past consideration when a promise is made subsequent to and in return for an act that has already been performed. Example: A finds and returns B’s digital camera and in gratitude, B promises to reward him with RM200. Here B made a promise in return for A prior act i.e. return his digital camera. General rule s. 26 of CA – “an agreement made without consideration, void”. Illustration (a) of s. 26 CA, 1950 A promises, for no consideration, to give to B RM1,000. This is a void agreement Exceptions to general rule 1. An agreement on account of natural love and affection s. 26 (a) of CA, 1950 The validity of this agreement is dependent upon the following condition:a) it is expressed in writing; b) it is registered (if applicable); c) it is made on account of natural love and affection between parties standing in near relation to each other. (near relation is varies from one social group to another as it depends on customs and practices of such group) English law does not recognize natural love and affection as valid consideration. 2. An agreement to compensate for something voluntarily done s. 26 (b) of CA, 1950 There are two (2) limbs to this exception:a) it is promise to compensate either wholly or in part the other person (promisee) b) the promisee has voluntarily done something for the promisor. So, the act that has been performed by the promisee prior to the agreement must have been performed voluntarily. Illustration (c) of s. 26 of CA, 1950 A finds B’s purse and gives it to him. B promises to give A RM50. This is a contract. 3. An agreement to compensate something which promisor was legally compellable to do The necessary ingredients are as follows:a) the promisee has voluntarily done an act b) the act is one which the promisor was legally compellable to do c) an agreement to compensate, wholly or in part the promise for the act. Illustration (d) of s. 26 CA 1950 A supports B’s infant son. B promises to pay A’s expenses in so doing. This is a contract. Example: If X pays a fine imposed by the court on Y who promises to compensate him, that promise is binding under this provision. 4. A promise to pay a statute-barred debt s. 26 (c) of CA 1950 A statute-barred debt refers to a debt which cannot be recovered through legal action because lapse of time fixed by law i.e. under the Limitation Act 1953 the time limit is 6 years from the time of cause if action arises. General rule is that where more 6 years have elapsed from the cause of action the aggrieved party cannot sue. s. 26 (c) CA, 1950 creates an exception to this rule but subject to several conditions namely:a) the debtor made fresh promise to pay the statute-barred; b) the promise is in writing and signed by the person to be charged or is authorised agent in that behalf. Illustration (e) of s. 26 CA 1950 A owes B RM1000, but the debt is barred by limitation. A signs a written promise to pay B RM500 on account of the debt. This is a contract. Elements of consideration 1. Consideration need not be adequate Explanation 2 of s. 26 of CA, 1950. An agreement is not void merely because the consideration is inadequate. Illustration (f) of s. 26 of CA, 1950 A agrees to sell a horse worth RM1000 for RM10. The sum of money obviously not adequate for his promise but the court will not assess whether a promisor has received adequate consideration. It appears that the adequacy of consideration is immaterial. However, Explanation 2 of s. 26 CA, 1950 further provides:the inadequacy of the consideration may be taken into account by the court in determining the question whether the consent of the promisor was freely given. Cases: Bolton v. Madden (1873) LR 9 QB 55 Held: The adequacy of consideration is for the parties to consider at the time of making the arrangement and not for the court when it is sought to be enforced. Phang Swee Kim v. Beh I Hock (1964) MLJ 383 Held: The transfer of land for RM500 is valid as there as was no evidence of fraud or duress. 2. Consideration may move from the promisee or any other person Authority s. 2 (d) of CA, 1950 states that:“…the promisee or any other person…” i.e. consideration can move from third party. Different position in English law – only who has paid the price of a promise may sue on it. It means consideration must move from the promisee i.e. the person who receives the promise must himself give something in return. Case: Venkata Chinnaya v. Verikatara Ma’ya Facts: A sister agreed to pay an annuity of Rs653 to her brothers who provided no consideration for the promise. But on the same day, their mother had given the sister, her estate subsequently failed to fulfill her promise to pay the annuity, her brother sued her on the promise. Held: She was liable on the promise on the ground that there was a valid consideration for the promise even though it did not move from the brothers. 3. Past consideration is good consideration Something which wholly performed before the promise was made. It was made or given not in response to the promise. Promise is subsequent to the act and independent of it. English law: Past consideration is not a good consideration. Malaysian law: Past consideration is a good consideration. Authority: s. 2 (d) of CA, 1950 : “…has done or abstained from doing”. The use of the words implies that even if the act is prior to the promise, such an act would constitute consideration so long it is done at the desire of the promisor. Case: Kepong Prospecting Ltd. V. Schmidt [1968] 1 MLJ 170 Facts: Schmidt, a consulting engineer has assisted another in obtaining a permit for mining iron ore in the state of Johore. He also helped in the subsequent formation of the company, Kepong Prospecting Ltd., and was appointed Managing Director. After the company was formed, an agreement was entered into between them under which the company undertook to pay him 1% of the value of all ore sold from the mining land. This was in consideration of the services rendered by the consulting engineer for and on behalf of the company prior to its formation, after incorporation and for future services. Issue: Whether services rendered after incorporation but before the agreement, were insufficient to constitute a valid consideration even though they were clearly past. Held: Past consideration did constitute a valid consideration. So Schmidt was entitled to his claim on the amount. 4. Part payment may discharge an obligation s. 64 of CA, 1950 “Every promise may dispense with or remit, wholly or in part, the performance of the promise made to him, or may extend the time for such performance, or may accept instead of it any satisfaction which he thinks fit”. General rule is that payment of a smaller sum is a satisfaction of an obligation to pay a larger sum. Illustration (b) to s. 64 of CA, 1950 A owes B RM5000. A pays to B. and B accepts in satisfaction of the whole debt, RM2000 paid at time and place which the RM5000 were payable. The whole debt is discharged. Illustration (c) to s. 64 of CA, 1950 A owes B RM5000. C pays to B RM1000 and B accepts them, in satisfaction of his claim on A. This payment is a discharge of the whole claim. Case: Kerpa Singh v. Bariam Singh Facts: Bariam Singh owed Kerpa Singh RM8.869.94 under the judgement debt. The debtor’s son wrote a letter to Kerpa Singh, offering RM4000 in full satisfaction of his father’s debt and endorsed a cheque for the amount, stipulating that should Kerpa Singh refuse to accept his proposal, he must return the cheque. Kerpa Singh’s legal advisor having cashed the cheque and retained the money, proceeded to secure the balance of the debt by issuing a bankruptcy notice to the debtor. Held: The acceptance of cheque from the debtor’s son in full satisfaction precluded them from claiming the balance. English law – in Pinnel’s case established that payment of a smaller sum is not a satisfaction of an obligation to pay a large sum. 6. INTENTION TO CREATE LEGAL RELATIONS Contracts Act is silent on the intention to create legal relation as one of the requirement of a valid contract. However, case law shows the necessity of this requirement. There are two presumptions have developed in the determination of intention with respect to agreements. However, the presumptions are rebuttable. (a) In social, domestic and family agreements. The presumption is that no legal intention to create legal relations. Relevant cases: Case: Balfour v. Balfour (1919) 2 K.B. 571 Held: In an agreement made between members of family in the course of family in the course of family life, the law will ordinarily imply from the circumstances of the case that the parties did not intend their agreement to have legal consequences. However not all social, domestic or family agreements are not legally enforceable. The presumption is rebuttable. Case: Meritt v. Meritt [1970] 2 All ER 760 Facts: The husband left his wife. They met to make arrangements for the future. The husband agreed to pay £40 per month maintenance, out of which the wife would pay the mortgage. When the mortgage was paid off he would transfer the house from joint names to the wife’s name. He wrote this down and signed the paper, but later refused to transfer the house. Held: When the agreement was made, the husband and wife were no longer living together, therefore they must have intended the agreement to be binding, as they would base their future actions on it. This intention was evidenced by the writing. The husband had to transfer the house to the wife. (b) In commercial agreements The presumption is that the parties intend to create legal relations and make a contract. 7. CERTAINTY OF CONTRACT Rule: The terms of contract must be certain and not vague Effect of uncertainty: s. 30 of CA: “Agreements, the meaning of which is not certain, or capable of being made certain, are void” Illustration (a) of s. 30: A agrees to sell to B a hundred tons of oil. There is nothing whatever to show what kind of oil was intended. But if A, a dealer in coconut oil only, agrees to sell to be ‘one hundred tons oil’, the agreement is not void for uncertainty because the nature of A’s trade afford an indication of meaning of the words Illustration (f) of s. 30: A agrees to sell to B “my white horse for ringgit five hundred or ringgit one thousand”. There is nothing to show which of the two prices was to be given. Where the meaning is unclear but it is capable of being made certain, the agreement is not void. Illustration (e) of s. 30: A agrees to sell to B ‘one thousand gantangs of rice at a price to be fixed by C’. As the price is capable of being made certain, there is no uncertainty here to make the contract void. Case: Karuppan Chetty v. Suah Tian (1916) 1 F.M.S.L.R The contract was declared for uncertainty because the parties agreed to a lease of S35 per month ‘for so long as he likes’. PRIVITY TO THE CONTRACT A person who is not a party to a contract has no right to sue on the contract. Example: If A enters into a contract with B, only A and B can enforce or sue on the contract. C who is not a party to the contract cannot do so TERMS AND CONDITIONS Contents of contract are made up of terms which may be express and implied. (i) Express term -Terms of agreement which the parties of contract have set out, in writing, verbally or mixture of the two (ii) Implied term - Terms of contracts which are so obvious that it goes without saying that the form part of a contract - Terms may be implied by: a) Custom and usage pertaining to a particular type of transaction; b) Statutory provisions; and c) The court based on the intention of parties. Express term and implied term are divided into:(i) Conditions -essential to the main purpose of the contract - if there is breach of condition, the injured party may rescind the contract and sue for the damages (ii) Warranties - collateral to the main purpose of the contract - less important terms compared to the conditions if there is a breach of warranty, the injured party may only claim for the damages