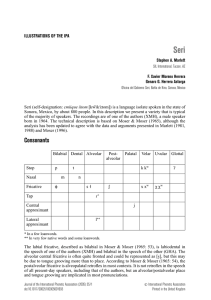

Changfei Shi LING 550B 4 June 2021 Mystery Language Project Seri [ISO-639 code sei], a language spoken by the indigenous Seri people of Sonora, Mexico, was the mystery language I was given as a topic of phonetic study. I transcribed words containing vowel and consonant samples, built vowel and consonant charts compiling phonetic information, and compared them to Praat spectrograms to verify my analyses. I made several errors during my transcription that deviated from S.A. Marlett, F.X. Herrera and G. Herrera Astorga’s summary of Seri, published in the Journal of the IPA in 2005 (Seri 2005.) Their article primarily focuses on giving a consonant and vowel inventory, which I used as a basis for verification of my own conclusions regarding the language. The article also provides notes on accent behavior and predictable stress and lengthening patterns, which provided some insight that I had not considered when examining patterns of suprasegmentals. Comparison of vowel analyses i i: e o oː eː ɛ ɛː a aː ɑ ɑː Figure 1. Comparison of vowel charts in Marlett vs. my vowel analysis. Vowels that I posited that were not present in Marlett’s paper are marked in red, while vowels in Marlett’s paper that I did not include in my earlier writeup are marked in blue. I was able to correctly identify four major vowel groups, as well as the phonetically significant length distinction between the vowels. However, my vowels differed in the actual phoneme identified: I chose to use the more common vowels /a/ and /e/, in line with the class material identifying the most common phonemes across the worlds’ languages; however, Marlett chose to use /ɛ/ and /ɑ/, which perhaps better represent the F1 and F2 values when compared to the average formant values of those vowels in other languages. Marlett notes that two morphemes with identical vowels can form an even longer vowel when juxtaposed when commenting on the length distinction in Seri. This is an intriguing find that I tried to verify, but no examples of such phenomena were provided among the language samples received. Comparison of consonant analyses. Table 1. Consonant charts compared. My consonant phonemes not matching the Marlett chart are marked in red, while Marlet additions not occurring in my chart are marked in blue. Bilabial Plosive p Nasal m Fricative ɸ Lateral fric. Approximant Lat approx. Click Tap Labio-velar Labiodental Dental Alveolar t t n s ɬ f w Postalveolar Palatal Velar Uvular k g kw ʃ çʝ x xw Glottal ʔ χ χw h j l | ɾ My transcriptions, and the consonant charts that I derived from them, were generally about 2/3s correct. Major deviations from Marlett’s consonant inventory came with the nonEnglish phonemes, which comprised about half the phonemes in the language. The difference between my transcribed consonant chart and the consonant chart provided by Marlett fall into a few general categories. Voiced stops/fricatives: According to Marlett’s analysis, obstruents in Seri are all voiceless. This was a trend I should have identified in the bilabial, labiodental, dental, and postalveolar places of articulation, but I failed to extrapolate it to the velar and palatal sonorants, and consequently ended up misidentifying certain unaspirated unvoiced stops like /g/ and /ʝ/ for voiced stops. Labial fricatives: I misidentified the unvoiced bilabial fricative /ɸ/ as the unvoiced labiodental fricative /f/. As an English speaker, these two sounds are hard to distinguish, especially when /f/ does not exist in Seri to provide a minimal pair. Analysis for this pair of fricatives would be easier with visual access to the speaker. Marlett notes that the labial fricative is labiodental in one of the two speakers providing data, so the actual symbol used for the labial fricative may still be correct depending on the dialect of Seri. Labiovelar stops: I was uncertain whether to classify /w/ as a standalone phoneme, or as a cluster. At the point in the class we’d reached when the consonant analysis was assigned, we hadn’t yet touched the methods used to analyze distinctions between standalone phonemes and consonant clusters, so I didn’t really have any basis for an argument resolving this sequence-segment problem. I had considered classifying the /w/ phoneme as part of a /xw/ cluster, but I had analyzed ‘Seri-self-designation’ having a standalone /w/ occurring wordinitially, in the transcription /wikeito/, which I considered as proof that /w/ was its own separate phoneme. In retrospect, this /w/ might have been preceded by a short /x/ that escaped my notice. Marlett does comment that ‘consonant clusters are common’ in Seri wordinitially and word-finally, interestingly, so other non labio-velar consonants may be part of a longer cluster. An example of a cluster occurring word-initially was /χpaːç/ ‘basalt’, which I transcribed correctly and could have cited as basis for clustering. Click: I mistook a sound artifact at the word-initial position of /ʔanax/ ‘raven’ to be an alveolar click. I should have second-guessed this conclusion, as clicks are relatively rare, and it is likely there would have been more examples of clicks in the corpus if they were a separate phoneme. Glottal fricative: The glottal fricative /h/ does not exist in Seri, according to Marlet, which makes sense in retrospect. I had confused /h/ with the velar fricative /x/, partially due to the previously mentioned lack of strength in the velar fricatives. Velar fricatives are difficult to identify from the spectrogram alone, as the noisy, aperiodic waveform characteristic of fricatives masks the “pinch” usually used to identify a velar of articulation. Alveolar/palatal fricatives: According to Marlett, no palatal fricative exists in the language. I mistook the lateral approximant /ɬ/ for the palatal fricative /ç/ in many of my transcriptions, not even realizing there was a lateral approximant in the language. Additionally, in certain cases (most commonly where the fricative occurred word-finally), I erroneously transcribed the alveopalatal fricative /ʃ/ as the palatal fricative /ç/, perhaps because the Seri /ʃ/ is somewhat more fronted than the English /ʃ/. Voiced velar stop: I disagree with Marlett’s transcription for /jen/ ‘his-her-its’-face’ – specifically with the word-initial /j/. It may not be specifically the velar stop /g/, but I believe the word-initial phoneme is some kind of voiced stop, as evidenced by the spectrogram in Fig. 2. A word-initial release burst is clearly visible, with voicing beginning prior to the start of the release burst. This negative VOT prior to a burst is not characteristic of an approximant like /j/, as far as I am aware. Figure 2. Spectrogram of 'his-her-its-face'. Notice the word-initial stop burst. Word-final stops: I misidentified several word-final stops. Seri stops are unaspirated, and the lack of stop aspiration word-finally, combined with a missing release burst that you occasionally get in English word-final stops, meant that some of these stops were not even visible in the spectrogram of a word like /ʔakat/ ‘shark’. I transcribed ‘shark’ as /aʔkaː/, missing both the word-final alveolar stop and the lengthened consonant. Seri also has an allophonic glottal stop prior to word-medial stops, that should not have been transcribed in the broad transcription. Word-finally, Seri seem to shorten stops even more than Seri word-initial stops (which already have VOT values in the ~20ms range). Figure 3. Spectrogram of Seri 'shark'. An abrupt end to voicing is the clue that might suggest a word-final stop. Suprasegmental analysis Marlett provides a brief description of stress formation on Seri morphemes, taking into account compound words and phrases. A contrast is noted between the stress on phrases, which usually occur syllable-finally on the last word of the phrase, and the stress on words, which usually occur word-initially. When multiple words are compounded into a phrase, the stress travels from the first syllable of the phrase to the final syllable of the phrase, though some secondary stress remains. While I did transcribe the lengthening of vowels, Marlett brings up an interesting point about lengthening of consonants in Seri following a long or short stressed vowel. In the transcription of ‘shark’, Marlett identified the lengthened consonant in his narrow transcription /ʔakːaːt/. Marlett also remarks on a predictable correlation between the consonant length and the degree of stress: lengthening varies as a function of stress, as evidenced from examination of secondary stress within sentences. Points of interest What intrigued me about the article after reading were the provided histories of the current development of the language: the language is spoken only by 800 speakers, yet Seri has experienced some relatively modern changes, such as the rounded consonants /kw/, /xw/ and /χw/ replacing an /o/ in the words where they occur. Confusingly, the article mentions that [o] and [u] are interchangeable in Seri when speakers pronounce Spanish loanwords. This makes sense given the proximity of the two vowels to each other and the lack of a high back rounded vowel in Seri. This mystery language project provided as many questions as it did answers. Though Marlett’s paper seemed comprehensive in its phonemic inventories and all its conclusions seemed correct after reconsulting the data, its analyses of words and phrases containing suprasegmental changes, such as stress behavior, did not have corresponding sound files in my corpus. Additional data (presumably available in the JIPA repository) is needed to verify Marlett’s conclusions. References Marlett, S., Herrera, F., & Astorga, G. (2005). Seri. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 35(1), 117-121. doi:10.1017/S0025100305001933