History of Science & Technology: Intellectual Revolutions

advertisement

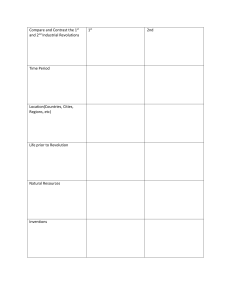

STS-1 On the History of Science and History of Technology In our quest to study the mutual relationship between science, technology, and society, we ought to revisit their history to find out what, where, when, how, and why ideas came to be. In a way, discussing scientific knowledge and technology in their corresponding social and historical contexts brings us back to the notion of “opening the black box.” This enables us to discover not only the underlying reasons for their creation, but also the factors that influenced their development. However, it is important to note that not all inventions and innovations can be explained through a sociohistorical lens, as many were created for the sake of practicality and efficiency. Nevertheless, delving into the past also gives us an idea as to how these apparatuses in turn have come to impact society and humankind as a whole. Various ways of knowledge-making can be traced back to the early civilizations. Even then, there were apparent cultural disparities that shaped the processes of scientific inquiry. The individualistic culture of Greeks led them to focus on the construction of theoretical knowledge through rational debate and empirical observations, and on establishing themselves and their schools of thought. On the other hand, collectivistic cultures such as, India, Mesoamerica, and China, prioritized the application of useful knowledge, which led to broader understandings of natural phenomena and the advancements of their societies. However, culture was not the only influence upon the creation of knowledge as the ideas of ancient and medieval thinkers were influenced by factors such as their immediate geography, state support, availability of resources, and individual life experiences. These early conceptions of science and technology became the foundations for the future. A hundred years and countless scientific and technological developments later, different intellectual revolutions surged in response to the increase of anomalies, each one building upon and uniting or disproving the claims of the previous paradigms. First, was the “scientific revolution” characterized by the split between religious and secular knowledge in Europe. This included the age of exploration, which supposedly facilitated the greatest exchange of resources, goods, and information. Conversely, the ethnocentric tendencies of European explorers led to the exploitation of the native inhabitants of the “new world.” Following this was the industrial revolution, which birthed many practical technologies that transformed society. Communication devices such as the telegraph, telephone, radio, and television, made the world smaller. However, the growth of factories as well as the invention of machineries and clocks stressed the importance for productivity, leading to implementation of working conditions that furthered class divisions. The impressive techne boom of industrialization called for need of epistemic knowledge to catchup. And catch-up it did with the works in thermodynamics, electricity, and the discoveries of Albert Einstein. These scientific breakthroughs gave way for even more impressive advances in the realms of biology, computer, earth and space sciences, leading all the way up to the information revolution. In a way, these intellectual revolutions were brought about by changes in phenomena caused by technological advancements resulting from discoveries of scientific inquiry. Humankind has basically constructed a dynamic cycle of knowledge creation in its quest to understand the cosmos. In addition to that, the attempt to answer the questions of “where we are” and “when we are,” is influenced by the sociohistorical and geographical location of those who make those attempts. However, this becomes problematic when the people involved in the process of investigation are limited to a specific when and where, possibly leading to the gatekeeping of scientific information and technology. Because after all, science is political, and “only as good or as bad as the humans who use them.”