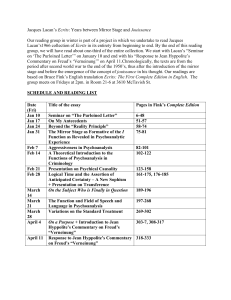

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive International Socialism, Winter 1980 Andrew Collier Lacan, psychoanalysis and the left (Winter 1980) From International Socialism, 2:7, Winter 1980, pp. 51–71. Transcribed by Marven James Scott. Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL. Freudians and Marxists The history of the relations between Marxist and psychoanalytical movements has been a complex one. Movements with different – though compatible – objectives, arising in different social circles, and arousing different ideological resistances in their audiences: combinations of them could not be expected to develop immediately. All the same, Freud’s colleague Sandor Ferenczi became the first ever professor of psychoanalysis under the short-lived communist government of Hungary in 1919; Trotsky and some other leading Bolsheviks defended psychoanalysis in Russia; and Wilhelm Reich pointed out the similarities of method between the two theories (in Dialectical Materialism and Psychoanalysis), the possibility of common social aims (in The Sexual Revolution), and the need to use both theories in order to understand the role of the irrational in politics (in The Mass Psychology of Fascism). The great downturn in prospects of co-operation came with Stalin. The suppression of psychoanalysis in Russia was part of the same puritanical programme which led to prison sentences for homosexuals, the prohibition of abortion, the preaching of sexual abstinence to students, the awarding of state prizes to particularly prolific mothers, and so on. In Russia and China the taboo on psychoanalysis still holds. In the west, once Marxists began to crawl out of the Stalinist wreckage of the movement, interest in psychoanalysis revived, reaching a peak in the late 1960s. Then, in the English-speaking world, a new anti-Freudian wave hit the left, originating in the feminist movement. The reversal of this process came from the same direction with Juliet Mitchell’s book Psychoanalysis and Feminism being probably the most outstanding contribution. But the new openness to Freudian ideas has for the most part latched on to one interpretation of Freud: that of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. My aim in this article is to ask whether the work of Lacan offers any new prospects for the cooperation of Marxist and Freudian theories and practices. I shall be concentrating on those aspects of Lacan’s interpretation of Freud which have political effects – which doesn’t mean that I favour making wholesale judgements of psychoanalysis on political grounds. On the contrary, I hope that one outcome of the interest in Lacan among Marxists will be that they will ‘render unto Marx what is Marx’s and unto Freud what is Freud’s’, rather than trying to produce a ‘Freudo-Marxist’ hybrid. Two aspects of Freud’s theory have scandalised the world more than others: his view that many of the sources of our experience and action are unconscious, and his stress on the role of sexuality in symptom – and character – formation. His successors have for the most part watered down these parts of his theory. The motive for this revision is easy to decipher: as psychoanalysis has become increasingly integrated into bourgeois culture, it has taken as a goal the ‘adjustment’ of the patient to circumstances. This goal is completely alien to Freud’s thought – he believed that changing oneself rather than the world was a neurotic response. [1] But in order to adopt as ones goal adjustment to external pressures, one must ignore the limits of conscious self-control, and play down the internal pressure of sexual needs which exact their price if frustrated. Those who have revised psychoanalysis in this way have generally also wanted to sever all links with its biological foundations, dropping the concept of ‘instinct’ or ‘drive’, which for Freud was always a border concept between psychoanalysis and the underlying biological sciences. [2] Lacan’s peculiarity is that, while he is scathing about ‘adjustment’ as a goal of therapy, and deplores ‘the eclipse in psychoanalysis of the most living terms of its experience – the unconscious and sexuality, which apparently will cease before long even to be mentioned’ [3], he shares the desire to keep his distance from biology, preferring to consort with structural linguistics. This package has proved attractive to the left, for ‘biologism’ – the explanation of social institutions in terms of biological instincts – has been a favourite ploy of the right. A version of psychoanalysis which retained all its subversive potential but didn’t require us to get our fingers sticky with biology would seem to offer the best buy. But the question remains whether his antibiologism doesn’t lead Lacan to domesticate these troublesome terms in another way. There is another feature of Lacan’s appeal to his Marxist admirers. It is thought that, whereas earlier psychoanalytical heroes of the left such as Riech, Marcuse or Laing were woolly thinkers who were bound to end up directing us towards transcendental mysticism rather than earthly happiness, Lacan is a rigorous scientist with a hard-headed approach to the goals of therapy. Althusser, for instance, proclaims that ‘Lacan’s first word is to say: in principle, Freud founded a science. A new science which was the science of a new object: the unconscious. A rigorous statement.’ (Freud and Lacan, in Lenin and Philosophy). Freud’s work may, as I believe, have been scientific but we shouldn’t take this too seriously about Lacan. The mystique of untranslatibility, and even incommunicability [4], which surrounds his work bears witness to this. Scientific terms have a precise meaning within the science, which is nothing to do with their nuances in ordinary language; untranslatibility is to be expected in a poem or a joke, and is no criticism of a novel, but it is a fault in a philosophical text, and damning in a scientific one. A scientist uses language to communicate, not to tantalize. Lacan’s defenders claim that his style is itself educative in the ways of the unconscious. But there is no good reason why a teacher of psychoanalysis should have to use a style that ‘provides a dumbshow equivalent of the language of the unconscious’ (Althusser, op. cit.) – any more than a teacher of canine behaviour has to bark. In fact Lacan himself wears his scientific cap at a very jaunty angle. Within one essay, he says that psychoanalysis is not yet a science, that it is a ‘conjectural science’, a ‘science of the particular’, and science in Plato’s sense rather than the modern one. [5] Although I believe there are many interesting things in Lacan’s work – valuable insights, disconcerting questions, exciting (but usually unverifiable) speculations, memorable witticisms – if we are looking for the rigour and informativeness that are characteristic of a science, we had better look elsewhere. Lacan’s version of psychoanalysis: (i) ‘The unconscious is structured like a language’ This idea is the foundation of Lacan’s work. In part, this stems from a re-assertion of a fact about psychoanalysis as a technique of therapy – that it is a ‘talking cure’, in which language is the only instrument at the analyst’s disposal. Physical symptoms and ‘body language’ can only be interpreted insofar as they ‘join the conversation’ as substitutes for repressed words. They don’t form an independent mode of access to the patient’s unconscious, as e.g. Reich assumed. But Lacan takes the linguistic connection a lot further than that. He certainly shows that the idea of the unconscious as a language is a very fruitful metaphor – but his claim is that it is not a metaphor: ‘if the symptom is a metaphor, it is not a metaphor to say so, any more than to say that man’s desire is a metonymy. For the symptom is a metaphor whether one likes it or not, as desire is a metonymy, however funny people may find the idea.’ (Ecrits, p. 175) [6] This assimilation of the unconscious to language is not just an aberration: firstly, in that it is one instance of structuralism – the whole intellectual movement based on the use of the structural linguistics founded by Saussure as the model for all the human sciences; and secondly because it is a conclusion (though I think a false one) drawn from what is really the most original and interesting part of Lacan’s work: his opening up for investigation (I put it no stronger) of the relations between the acquisition of language and the formation of the unconscious in a human subject. Structuralists have directed attention in the human sciences away from people and things, towards relations. There is of course some common ground with Marx here. Just as theories of language before Saussure tended to see meaning as a relation between a word and the thing it named, so, until Marx, property was generally seen as a relation between an owner and the goods owned. Saussure showed that a word got its meaning purely by its relations to other words; it is the boundary between the possible correct uses of the word and those of other words that determines its sense. Thus the English word ‘sheep’ gets its meaning by its contrast with ‘cow’, ‘lamb’, ‘mutton’ etc. The contrast between ‘sheep’ and ‘mutton’ doesn’t occur in the French word ‘mouton’ which covers both. [7] Likewise for Marx, property is a relation between agents (people or institutions); it is the relative power of these agents over the goods that determines the latter’s character as property. But the analogies shouldn’t be pushed too far. Apart from an arbitrary sound, there is nothing to a word but its place in the set of relations that constitutes the language. If the word ‘radio’ replaces the word ‘wireless’, the structure is unaffected, and the discarded word disappears; if a worker is replaced by a robot, the structure is affected, and the worker doesn’t disappear. It is arguable that the ‘materialist’ character of Marx’s theory rests on his recognition of the constraints placed on possible social structures by the nature of their ‘material’ (human, environmental, technical). This raises a query about the applicability of the method derived from Saussure to structures whose elements have their own material nature. It has been alleged, for instance, that Levi-Strauss, in his structural analysis of kinship relations, loses sight of the content of these relations in his fascination with their form. Perhaps as a result of this, the taboo on incest comes to be seen as an invariant given of human culture, rather than something needing explanation, as it was for both Marx and Freud (who rightly or wrongly thought that it had an origin within history). The incest taboo is of course a necessary condition of the Oedipus complex and Lacan takes his cue from Levi-Strauss on this point. According to Lacan, a child enters culture – becomes human – only as a result of an intrusion into the original bond with the mother. The intruder is typically the father. (One of the problems about this is that it is never really made clear how much, if any, of this is an effect of particular family structures which could be changed. But some form of Oedipus complex, splitting the subject into conscious and unconscious as the price of entry into human culture, is assumed to be unavoidable by Lacan.) Language is acquired, it would seem, as a way of coping with the mother’s absence, in that language enables us to evoke and invoke absent beings. But Lacan also insists that the acquisition of language is not an effect but the cause of the splitting of the subject. It is as if having a word for something alienates one from it. In particular, it is suggested that, by the very fact of naming ones desire, one renounces it. I see no reason to accept this idea. We know that it is no use giving a starving man a menu, but it doesn’t follow that there is anything impossible about having both a menu and a meal. This idea of language as inherently repression-inducing is very reminiscent of romantic irrationalism, and there is certainly an irrationalist streak in Lacan. He is openly contemptuous of logic, for instance (see Ecrits, p. 140). All the same, he does see repression as involving inability to put ones desire into words, and cure as involving the ability to do so. If repression comes by language, it is by language too that it is overcome. So much for the origins of the unconscious in language-acquisition. As we have seen, Lacan also holds that the mechanisms of the unconscious are those of language. This is unsatisfactory both from the point of view of linguistics and that of psychoanalysis. Saussure insisted that his science could apply only to systems of arbitrary, ‘unmotivated’ signs. The relation between the ‘cow’ and a cow is purely conventional; the relation between the phallus as a symbol and the penis as a physical organ is not. From the psychoanalytic side: any similarities between the unconscious and language have been discovered by the methods of psychoanalysis, not those of linguistics. So we can’t simply generalise from established linguistic theory and draw conclusions about the unconscious – that would be like thinking that electro-magnetic waves must taste salty. It is up to psychoanalysis to show just what the similarities and differences are between the mechanisms of the unconscious and those of language proper – between, for example, displacement and metonymy, which Lacan simply equates. If we simply treat the two sciences as if they were one, we lose sight of what is original in Freud’s discovery. There is an example in the Macciocchi-Althusser correspondence, where Macciocchi refers to a fellow Communist candidate opening his speech: ‘On this historic 5 May ...’ – in fact, a perfectly ordinary day; she suggests that he associated the date with that of Napoleon’s death, and calls this a ‘Freudian phenomenon’. [8] She clearly doesn’t mean that it was the displaced expression of a repressed wish. The implication is simply that it is a random association, not an intelligible connection. If that makes it ‘Freudian’, all slips would have to be Freudian, and Freud’s explanation of slips would lose its content. In fact the Italian Marxist Timpanaro has tried, as part of a case against Freud, to explain some of the slips recounted by Freud in terms of purely linguistic mechanisms. One such mechanism is banalization, i.e. the use of a familiar word or construction where an unfamiliar one is required. For instance, people who are more familiar with The News of the World than with the Bible, will often call the Book of Revelation the “Book of Revelations”. Such cases are like Freudian slips only in that the connection between the words required and the words used is one of verbal association not meaning. The motivation is quite different. Here is an example from Freud: ‘A lady once expressed herself in society – the very words show that they were uttered with fervour and under the influence of a great many secret emotions: “Yes, a woman must be pretty if she is to please the men. A man is much better off. As long as he has five straight limbs, he needs no more!”’ [9] Freud himself points out that the (purely associative) condensation of ‘five senses’ and ‘four limbs’ has occurred here. But the motive is all too clear: to express the repressed thought: ‘the fifth limb must be straight too’. If this aspect of the Freudian slip – the pressure of a repressed thought for expression – is left out, we have a purely linguistic theory of slips – and hence an unFreudian one, which is what Timpanaro wants. This should remind us that the idea that unconscious wishes press for fulfilment is essential to Freud’s theory. Slips, dreams, symptoms are so many ways in which the instinctual energies with which unconscious ideas are charged can be released. It is just this reference to instinctual energy which distinguishes Freud’s account from Timpanaro’s – and which over-use of the linguistic model tends to suppress. It is impossible to understand Freud’s use of terms like ‘condensation’ and ‘displacement’ without referring to the economies of energy achieved by getting two wishes past the censor in one disguise (condensation) or allowing emotion to be expressed while the idea that caused it remains repressed (displacement). Freud consistently regards displacement as an effect of repression, a means of at once appeasing and evading the ‘censorship’. But for Lacan, as ‘metonymy’, it is the nature of all desire. The dynamic explanation which would refer us back to socially induced prohibitions disappears: desire is ‘just like that’ – it keeps switching about. Lacan is not the only commentator on Freud who wants to keep the interpretation of symptoms while rejecting the ‘economic standpoint’ – the idea that instinctual energies not expressed in sexuality will get expressed as neurotic symptoms. This is the orthodoxy among philosophical interpreters of Freud, whether British linguistic philosophers or continental phenomenologists. I shall return to the ideological significance of this. ii. Reclaiming the id or subverting the ego Another effect of Lacan’s conception of the relation of conscious to unconscious, concerns his notion of the therapeutic tasks of analysis, as well as the whole theory of the ‘agencies of the psyche’, the ego, superego and id – an aspect of Freudian theory which he treats very cavalierly. [10] According to Freud, the unconscious has peculiarities other than its defining one of consisting of ideas excluded from consciousness, yet still effective on the person’s experience and behaviour. It consists largely of residues of childhood which, because they have been shut off from consciousness by repression, have remained in an infantile state. They obey different laws from those of consciousness. Because consciousness has the task of directing our interaction with the real world, it must tend to keep its ideas consistent and test them against reality. But the unconscious is quite happy to hold contradictory ideas; it expects wishes to be translated into reality without any action being taken; it confuses words and things, and delights in childish puns, associating ideas on the basis of verbal similarity rather than real connections; it attaches emotional significance to trivial matters which have some accidental connection with the real cause of the emotion. [11] So there is nothing particularly wise or authentic about the unconscious. If we are sometimes consistent and realistic enough in our projects to get what we want, all the credit must go to the conscious (or in terms of the ‘three agency’ model, the ego). If this is so, we must surely accept Freud’s conclusion that the aim of psychoanalysis should be: ‘to strengthen the ego, to make it more independent of the super-ego, to widen its field of perception and enlarge its organization, so that it can appropriate fresh portions of the id. Where id was, there ego shall be. It is a work of culture – not unlike the draining of the Zuider Zee.’ [12] This prospect of increasing our self-awareness and conscious self-direction was one of the aspects of Freud’s work that appealed to Trotsky, who hoped that under socialism mankind would be able to ‘raise his instincts to the height of his conscious mind, and bring clarity to them, to channel his willpower into his unconscious depths’. [13] No doubt Freud would not be so optimistic as to think that the whole of the unconscious could be dragged up into the light of day and controlled, but the direction of his work is the same. Many have been offended by this, and the typical ploy is to portray Freud as a cold monster who despised the emotional side of life, and brought the dreaded bogey of Science into the sacred precincts of feeling (though why a feeling should be any less of a feeling for being understood, I can’t imagine). [14] This well-trodden path of criticism starts by attacking ‘reason’ as repressive, hostile to our feelings and desires, but ends by urging us to bow before an irrational ‘intuition’ which turns out to be the voice of our outworn prejudices. ‘The heart too has its reasons of which reason knows nothing’ said Pascal, to entice us into the monastery. Freud on the other hand said ‘there ego shall be’ not ‘super-ego’ – in other words his ‘rationalism’ was never hostile to feelings and desires, only to the contradictory properties that prevent their fulfilment. Lacan takes his starting point from a different aspect of the relations between conscious and unconscious. In introducing the notion of the unconscious Freud himself had drawn attention to the gappy nature of consciousness – the fact that we forget things and later remember them, or repress them and can’t remember them without psychoanalytic help, and that the apparent coherence of consciousness is often a result of the processes of displacement and rationalisation by which we cover our traces. As Freud puts it: ‘We are not used to feeling strong affects without their having any ideational content, and therefore, if the content is missing, we seize as a substitute upon another content which is in some way or other suitable, much as our police, when they cannot catch the right murderer, arrest a wrong one instead.’ (Collected Papers, vol. III, p. 314) Lacan wants to stress this gappiness or illusory unity of consciousness. However for Freud these elements of irrationality in consciousness are the effects of the pressure of unconscious wishes on it. By making these wishes conscious, we are enabled to establish a real in place of an illusory coherence. Lacan’s model is at least different in emphasis. His attacks on philosophers’ prejudice of the unity and autonomy of the ego or of consciousness are a much-hailed feature of his theory – and there is certainly a sense in which he is right about this. If the unconscious plays as large a role in human life as Freud says it does, such unity and autonomy as human personalities have must be a relative unity and autonomy, an achievement of the ego, not the absolute unity and autonomy claimed by philosophers from Descartes to Sartre. But Lacan is saying more than this. His model seems to be of consciousness as a fragmented text of which the original is complete in the unconscious. The goal of promoting the relative autonomy and coherence of the self at the level of consciousness or ego is seen as misconceived; truth inhabits the unconscious. The ego is cast in the villain’s role – the source of the mystifications which obscure the true text, preventing the subject’s ‘truth’ from being put into words. The aim of treatment is to find the subject’s ‘full word’ in place of the ‘empty word’ of the ego. This is a strange mixture of restatement, distortion and inversion of the Freudian idea of the goals of analysis. On any account analysis aims to enable the analysand to formulate in words previously repressed wishes; but Freud saw this as bringing new areas of the mind into the sphere of influence of the ego; Lacan sees it as getting the repressive ego off the back of the ‘subject’. It seems to me that one source of the distortion is that Lacan confuses the ego with the super-ego. He objects to strengthening the ego as a goal of treatment because ‘repression proceeds from the ego’. Freud says this in his paper on Narcissism (Collected Papers, vol. IV, p. 50), but immediately corrects himself: ‘from the self-respect of the ego’ – and from this notion, he develops the idea of what he came to call the super-ego. So the post-Freudian advocates of adjustment who talk about strengthening the ego when they mean making repression more effective, are not talking the same language as Freud; for Freud, the strong ego was one which had incorporated more of the psyche, not one which had excluded (repressed) more. Lacan, despite his new terminology, seems to be accepting the basic mistake of the egopsychologists who he dislikes so much (ie confusing the ego with the super-ego), and simply inverting their value-judgement. This is not a new position; there have always been those who wanted to found a romantic irrationalism on psychoanalysis, treating the unconscious as the authentic self and source of deeper wisdom. In fact, this is nothing more than a reversion to the pre-Freudian dualism of ‘head’ and ‘heart’, whichever side is taken. The ‘head’ (’ego’ in the post-Freudians) is generally made to include both the rational functions of reality-testing, logic and conscious activity that Freud assigns to the ego, and the repressive functions that he assigns to the super-ego. Once this dualism has been set up, the only question is which side to take: the partisans of the ‘head’ (egopsychologists) end up peddling ‘adjustment’, while the partisans of the ‘heart’ end up in the ‘don’t think, feel!’ syndrome, which undermines the possibilities of criticism and change, if we want to avoid these alternatives, we would do well to keep Freud’s threefold distinction. Lacan rejects the idea that perception and motility are available to the ego, and uses ‘ego’ almost in its colloquial American sense, to refer to the self-fascination of the subject, originating in the toddler’s ‘jubilant’ self-recognition in the mirror (see his paper on The mirror stage, in Ecrits). One is left with the impression that there is nothing in the mind which can know and act on the real world – which makes the pessimistic views that I discuss in the following section less surprising. iii. Sexuality Psychoanalysis is concerned with the place of sexuality in the mental life of men and women, rather than with the physiological processes involved. Its source of information on sexuality is entirely through people’s words, and the unconscious wishes revealed in these words. Lacan is quite right to point out that psychoanalysis has nothing to teach us about erotic technique (see e.g. Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis p.266). But the recognition of this distinction between psychoanalytical and physiological studies of sexuality (each valid in its own sphere), need not lead to a dualistic split. A psychological event – sexual desire – can have physical causes and effects. Does this really need to be said? Unfortunately, it does. According to Lacan, human desire has to ‘pass through the defile of the signifier’ – that is to say, its nature is affected by the fact that we are language-users. So far so good; the question is: does it come out the other side? Lacan’s account often seems to require a different metaphor: desire is becalmed in the Sargasso Sea of the signifier. At the centre of Lacan’s account is his distinction between need, demand and desire. Rather than give my own exposition, I will quote the translator’s note on these concepts: ‘The human individual sets out with a particular organism, with certain biological needs, which are satisfied by certain objects. What effect does the acquisition of language have on these needs? All speech is demand; it presupposes the Other to whom it is addressed, whose very signifiers it takes over in its formulation. By the same token, that which comes from the Other is treated not so much as a particular satisfaction of a need, but rather as a response to an appeal, a gift, a token of love. There is no adequation between the need and the demand that conveys it; indeed it is the gap between them that constitutes desire, at once particular like the first and absolute like the second. Desire (fundamentally in the singular) is a perpetual effect of symbolic articulation. It is not an appetite: it is essentially eccentric and insatiable.’ [15] Now what is said here about need and demand may be quite illuminating, but when it comes to desire, this exposition seems to me to say nothing at all. This also applies to Lacan’s own writings on the subject, which strike me as systematically evasive, exactly like someone in analysis who has a resistance about the matter. He will have recourse to geometrical and mathematical analogies, which I find singularly unhelpful – for example the ‘gap’ referred to above. But what does emerge from them is that Lacan thinks that, though need is satisfiable, desire is not. This is a worrying conclusion in more ways than one. It smacks of world-weary philosophies of resignation – Stoicism or Buddhism, perhaps, but hardly psychoanalysis (let alone Marxism). For psychoanalysis, insofar as it has not degenerated into a means of adjustment, is supposed to remove internal obstacles to real satisfaction. [16] If satisfaction is impossible anyway, we might as well keep our analyst’s fees to spend on whisky. But the fact that a theory is unwelcome, dangerous, even selfdefeating, doesn’t prove it is false, so we had better see what Lacan’s reasons for this strange idea are. I think there are three aspects of the idea, two of which come straight from the thought of his compatriot and contemporary, Jean-Paul Sartre. [17] Only the third can claim Freudian credentials. In the first place, desire might be unsatisfiable because it is not that sort of thing at all: it has no aim that could be satisfied. According to Freud, desire has three referents in the real world: its source (the part of the body from which it arises), its aim (the activity that would satisfy it) and its object (the being – except in cases of fetishism, the person – that is desired). [18] Perhaps for Lacan (as also for Sartre) desire has an object but no source or aim. If this is what is meant, the choice of the word ‘desire’ is unfortunate, for this word is normally used precisely to refer to a feeling that does have an aim. We have other words (eg ‘affection’, ‘attraction’, ‘love’) for more diffuse and less goal-directed sexual feelings for someone. This idea of ‘aimlessness’ – or what is the same thing, indifference as to aim – certainly coincides with what Lacan says about the drive (or instinct). He argues from the possibility of ‘sublimation’ (one of the unclearest concepts in the Freudian lexicon), to the idea that all activities are equally satisfactions of a drive. [19] But in that case, there is no sense at all in calling the drive ‘sexual’. Freud is often accused of so extending the concept of sexuality as to make it meaningless; Lacan certainly does so. If all aims are equally Sexual, it doesn’t even make sense to call some and not others ‘sublimated’. Another idea that Lacan shares with Sartre is that desire is essentially directed towards the other person’s desire or pleasure. Lacan plays on the ambiguities of the phrase ‘desire is the desire of the other’: desire for the other, the other’s desire, or desire of the (upper case) ‘Other’, in the somewhat mysterious sense in which Lacan calls the unconscious ‘the discourse of the Other’. We are referred back to the infantile wish to be the object of the mother’s desire, but somewhere in the offing, I suspect, is the Sartrean idea that if desire is the desire to be desired, an infinite regress is generated. Certainly, attention is being drawn to a real and important aspect of desire, an aspect perhaps better described by Laing: ‘Any theory of sexuality which makes the ‘aim’ of the sexual ‘instinct’ the achievement of orgasmic potency alone, while the other, however selectively chosen, is a mere object, a means to an end, ignores the erotic desire to make a difference to the other. When Blake suggested that what is most required is ‘the lineaments of gratified desire’ in the other, he indicated that one of the most frustrating possible experiences is full discharge of ones energy or libido, however pleasurable, without making any difference to the other.’ (Self and Others, p. 85) But this account gives full due to the idea that desire aims at the desire of the other, without suggesting that there is anything impossible about the satisfaction of such desire, as Lacan (and Sartre) appears to think. Even so we should not imagine that this is some universal and necessary feature of human sexual desire. It is culturally determined and historically relative. There are societies that practise female circumcision, which can destroy a woman’s capacity for sexual pleasure. Do the men who uphold this brutal practice desire the other’s pleasure? Finally, there is the interpretation of the claim that desire is unsatisfiable which might be based on Freud’s theories: this is to do with the role of displacement. Every sexual desire is a ‘substitute’ for the original desire of the infant for the parent of the opposite sex. A good deal of this aspect of Lacan’s theory comes from his un-rigorous use of translation. ‘Desir’ is the French translation of Freud’s ‘Wunsch’, as well as of some other German words.’ Wunsch’, usually rendered as ‘wish’ in English, has a technical sense in Freud, which is not the same as the ordinary sense of ‘desire’ in English or ‘desir’ in French. No doubt we all have a wish to make love to our parents; few people desire to do so. This distinction is lost in Lacan’s work. Yet one aim of psychoanalysis is to free people’s desires from interference from unconscious wishes left over from infancy. A wish, for Freud, is a memory-trace of a past satisfaction, which therefore bears a positive emotive charge (’cathexis’). As such, it is on the one hand a necessary mediator between the blind biological need of the infant and desire which is satisfiable in the real world; and on the other hand a childhood residue which, if hidden from the light of consciousness, can afflict the desires of the present with feelings appropriate only to long past situations. Laplanche and Pontalis, in their entry on Wish (Desire) in The Language of Psychoanalysis, mention that the French translation obscures distinctions made by Freud. Yet they get into irresoluble contradictions in their attempt to accommodate Freud’s thought to Lacan’s. They says that ‘The search for the object in the real world is entirely governed by this relationship with signs’, yet they allow nothing – neither desire nor need – to be both mediated by signs and satisfiable in the real world. They say that ‘need, which derives from a state of internal tension, achieves satisfaction through the specific action which procures the adequate object’ – somehow, it seems, mysteriously overshooting the defile of the signifier. Desire, on the other hand, ‘is not a relation to a real object independent of the subject’. They are asking us to believe, then, the following inconsistent statements: (a) nothing can relate to objects in the real world except by mediation of signs; (b) nothing mediated by signs can relate to objects in the real world; (c) something (i.e. need) can relate to objects in the real world. I think the source of this inability to give an account of desire as something satisfiable is the Chinese Wall that Lacan builds between biology (need) and psychology (desire). To be sure, need in human beings ‘passes through the defile of the signifier’ and acquires all the complexities of a specifically human desire. But it remains need. [20] For Lacan, though desire is not a transformation or complexification of need, but an effect which need has on realities of a different order – like the rattling of pans when a singer practises her top notes in the kitchen. The need remains unaffected by the effects it may have. Lacan’s theory is unable to understand the nature of sexual desire as at once a complex desire composed of many layers of meaning and situated in relationships in which many emotions are invested, and at the same time a ‘physical’ need which can be satisfied only by a sexual act. By driving a wedge between the psychological richness of desire and its physiological urgency, it reproduces the moralistic idea of a gulf separating ‘love’ and ‘lust’. Sexuality ceases to have much to do with what people do in bed, and need is relegated to a lower league, where presumably all that matters is detumescence. Lacan’s influence on the left: (i) Althusser, ideology and ‘anti-humanism’ Lacan is not a Marxist, nor does he appear to have a clear political position [21] though his writings are spiced with a few vaguely anti-capitalist remarks. In France, his influence is not limited to the left; it includes the right-wing ‘New Philosophers’. Even in Britain, where his influence has mainly been among people with a leftish orientation, it has, I think, had a de-politicising effect. This may be due less to his psychoanalytical work than to his tendency (common to much recent French thought) to disregard realities outside of language, and assume that ‘discourse’ is sufficient unto itself. But there are two more specific ways in which Lacan’s ideas have influenced recent socialist thought – whether for good or ill – and these require separate treatment. They are (i) his influence on Althusser’s theory of ideology, and ‘anti-humanism’, and (ii) the use to which certain feminists have put his theories in analysing patriarchy. In his essay Ideology and the State [22] Althusser puts forward the view that all ideology ‘interpellates’ (hails) the individual as a ‘subject’; that is to say, addresses the individual in such a way as to give him or her to understand that he or she is an autonomous agent, rather than a product of a definite society, limited by a definite class position. He uses the example of religious ideologies, but the root illusion of liberalism is very similar: the idea that freedom and ‘human rights’ are something we ‘naturally’ possess so that all that is necessary to secure them is to keep the state at bay, rather than something that can only be secured by real collective control of social forces. Or again, there is the attempt to atomise trade unionists by appealing to ‘individual responsibility’, or to blame the unemployed for the non-existence of their jobs; it is assumed that it is the choices of individuals that explain social processes, rather than vice versa. The success of this ideological mechanism can be explained in Freudian/Lacanian terms by the narcissistic fascination of the individual by an ego-ideal. Ideology flatters our belief in ourselves as autonomous subjects, and distracts from the brutal facts of class exploitation. The same narcissism contributes to the resistance to the great scientific revolutions – to the Copernican revolution which showed that we are not the centre of the universe, to Darwin’s proof of our continuity with other animal species, to Marx’s demonstration that we make history as bearers of definite class positions, not as autonomous subjects, and to Freud’s discovery of the unconscious roots of our action and experience. This ‘ego-centricity’ (in a Lacanian sense of ‘ego’) forms a universal ‘structure of misrecognition’ to which specific class and traditional ideologies give content. [23] Given favourable circumstances, we (all of us – not just an elite) are capable of understanding the results of these scientific discoveries, and basing our actions on them rather than on flattering illusions. But it remains that we can’t (any of us – not even an elite) jump out of our skin to the extent of escaping ideological consciousness altogether. Just as we see the sun rising and setting, even after Copernicus, so we will presumably go on expecting our friends and lovers to treat us as unique and irreplaceable individuals, even when we understand the sources of our narcissism, and whatever sort of society we live in. We live in ideology even when we understand its illusoriness; but such understanding can offset its worst effects in practice. This, I take it, is in outline the theory of ideology that Althusser develops on Lacanian foundations. Perhaps an understanding of its origin and nature will prevent the misattribution of elitism to Althusser. It might also prevent the misinterpretation of his ‘anti-humanism’ as a lack of concern for the problems and feelings of individuals. The very fact that Althusser takes psychoanalysis seriously should be enough to dispel that idea. ‘Anti-humanism’ is indeed not only derived from Lacan; it was common ground of the structuralisms that dominated the French intellectual scene until recently. But it is also a corollary of this theory of ideology. ‘Humanism’ in the relevant sense is the theory that interposes autonomous human subjects between the history that makes us and the history that we make. ‘Anti-humanism’ doesn’t of course mean denying that there are human agents; it means taking this agency as something to be explained, not a mysterious break in social explanation. I am not urging that we should accept Althusser’s theories in their entirety, but I hope that recognition of his Lacanian sources will help to avoid the common image of him as a technocrat and a misanthropist. ii. Patriarchy and ‘cultural revolution’ The founders of Marxism assumed that the oppression of women was bound up with capitalist (and other class-divided) societies; the manner and degree in which women were oppressed was the best index of the nature of exploitation in any society; and there could be no reason why the oppression of women would survive into a classless society. [24] I have yet to be convinced that they were wrong about this; to explain the oppression of women under capitalism, one need look no further than the advantages that accrue to the capitalists and their state from the super-exploitation of women at work, their oppression in housework, and their use as a reserve army of labour – and it doesn’t take a genius to work out the effects of all this on the family, education and other ideological apparatuses. Naturally, the fact that these effects have economic causes doesn’t in any way detract from their reality or from the need to struggle against them as forms of oppression. But such struggles, though not purely economic, are in a broad sense political, and can be revolutionary. They consist in collective action to destroy oppressive institutions: they don’t take place on the analyst’s couch. All the ideological and psychological ramifications of women’s oppression, then, can be explained in the last analysis as effects of economic exploitation. [25] Certainly psychoanalysis has a great deal to tell us about these effects – about the process by which masculine and feminine characters are formed within the family; and it may – as a therapeutic practice – help individual men and women to free themselves from these effects. But in recent times, more has been claimed for it that this: it has been claimed that it makes an essential contribution to the theory of patriarchy – not just of its psychological effects – and therefore has a necessary place in any theory of women’s liberation. It is in this connection that Lacan is invoked as the rectifier of psychoanalysis – often along with Mao as the rectifier of Marxism (a significant conjunction, I think). [26] In order to find the right place for psychoanalysis in this matter, we must distinguish two perspectives on women’s liberation which can be broadly described as Marxist and radical feminist. Oversimplifying a bit, one can say that radical feminism regards the distinction between masculine and feminine characters as causing the oppression of women, its own causes being transhistorical; Marxism on the contrary regards the oppression of women as causing masculine and feminine characters, its own causes being socio-economic. In the radical feminist account (as in sexist accounts) men and women are seen as existing prior to the concrete societies in which women are oppressed, so that ‘men’ can then arrange those societies to their own advantage. The Marxist account on the other hand implies that there are no ‘men’ or ‘women’ except as products of concrete sexist societies – though of course there are biologically male and female individuals. In political terms, this means that economic equality and the economic independence of any individual on any other individual will be the foundation of sexual freedom and equality. The task of human liberation, in all its forms, is seen as one of removing restraints placed by existing society on existing possibilities of human development. The aim is to make people as free as material circumstances permit to direct their own lives, and not to mould a ‘New Socialist Humanity’. That is one of the meanings of the Marxist rejection of ‘utopian socialism’. [27] It is necessary to say this because recently, self-styled ‘Marxists’ have often stood Marx on his head and aimed at forcing people into some ideal mould as a condition of social change – a programme which reached its bloody climax in Kampuchea, where the Pol Pot regime virtually tried to commit genocide against its own people, and repopulate the land from a handful of the uncorrupted. The relevance of this to the debate over psychoanalysis and feminism is that broad sections of the feminist movement have adopted the Maoist idea of ‘cultural revolution’, separate from the social revolution, as a necessary condition for the overthrow of patriarchy. This is despite the fact that Mao’s cultural revolution had nothing to do with sexual freedom or equality – it didn’t even give women equal pay, or abolish the death penalty for homosexuals. [28] The reason that the Maoist interpretation of Marx and the Lacanian interpretation of Freud appeal to the same groups, I suggest, is that for both the action takes place at the level of ideas, rather than by changing material circumstances. A traditionally Freudian account by contrast seems to fit better with a traditionally Marxist one. If we look at Freud’s account of character-formation, we find children internalising the family as a result of relations of love, envy, identification and so on towards their parents and siblings. The child’s conception of its family will not be altogether realistic, as it will be affected by wishful and fearful phantasies; but the starting point of the child’s development is its real human environment. Different types of parent, different relations between parents, different treatment by parents will all have effects on the child’s personality. So if a socialist revolution leads to a change in familystructure, we can expect a new generation to have a new character-structure – for instance, to be less constricted by gender stereotypes. In this sense, Freud’s theory is thoroughly materialist: ‘existence precedes consciousness’ – real biological needs and real social relations precede and ultimately determine mental life (whether conscious or unconscious). Certainly, mental life has ‘relative autonomy’ – if it were not so, there would be nothing for Freud’s theory to be about. But Freud had a fair idea of the limits of psychoanalysis in the face of problems of social origin. [29] There is no reason to doubt that he was serious when he said that a real change in the relations of human beings to possessions would be more help than any ethical commands. [30] One gets a very different impression from Lacan. We no longer hear much about fathers – but a great deal about the Name-of-the-Father, the Law of the Father, and so on. These notions seem to be independent of particular family structures. And it is not a matter of the real experience of the child producing certain illusions, as in Klein’s idea that the ‘internal father’ is often more severe than the real prototype. It is rather that the acquisition of language, and hence the becoming-human of the child, which coincide with the Oedipus complex according to Lacan, subject the child to a sort of mythological patriarchy, whose relation to the real power of real fathers is quite unclear. I don’t presume to comment on the clinical value of all this. No doubt an analyst does have to deal with symbolic and imaginary fathers with little relation to their real prototypes. My bone of contention is less with Lacan than with the uses made of his theories by ‘cultural revolutionaries’ – uses in which he himself is not interested. For insofar as one is concerned with the phantasies of the patient on the couch, one may have to talk in mythological terms; but we may still be able to explain such mythologies in terms of the real structure of the family in a given society; and when we come to try to transform that society, it is real relations we are attacking, not mythological ones. In this connection, we need to keep Marx’s fourth thesis on Feuerback in mind: ‘... once the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be criticised in theory and revolutionised in practice.’ The danger for the Lacanian left is that it will regress to Feuerback and see the ‘holy family’ as the real enemy. For instance, Juliet Mitchell says in her book Psychoanalysis and Feminism: ‘It is the specific feature of patriarchy – the law of the hypothesized pre-historic murdered father – that defines the relative places of men and women in human history.’ [31] It is one thing to fight for women’s equality, gay rights, abortion on demand, and communal nurseries. But if the principal enemy is a long dead ancestor who in fact never existed, we are going to need a new strategy altogether. Perhaps the answer is to restore the Nibelung’s ring to the Rhinemaidens. My point is that the idea of carrying out a political revolution within the realm of unconscious phantasy is an illusion. Attempts to act directly on the unconscious by political means lead straight to 1984. At the same time, the world of phantasy is in the last analysis produced by real material conditions [32], and I see no reason to believe that a patriarchal unconscious could long outlive a patriarchal society. In the meantime it is necessary to keep concrete political attacks on sexual oppression in the foreground, and not to let them get buried under notions of liberation within the limits of pure ‘discourse’. If we are to understand the relations between ‘the personal’ and ‘the political’, we must avoid any too-easy identification between the two. If we read Lacan, let us read him as a psychoanalyst, and not expect to cull any theory of cultural revolution from his work. Probably psychoanalysis has little to offer politically, except as a by-product of its therapeutic work – i.e. a non-neurotic revolutionary will be a better one than one who is using politics as an outlet or a prop. Notes All references to Lacan’s books are to the English translations, namely: Ecrits: A Selection (Tavistock Publications, 1977). This is in English, despite the infuriatingly pretentious gimmick of leaving the title untranslated. And: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (The Hogarth Press, 1977). I am grateful to Marie-Noelle Lamy and Peter Sedgwick for providing information, and to Mike Westlake, Anthony Easthope, Tirril Harris and Peter Binns for criticising an earlier draft. Naturally, the opinions are mine alone – and I blame the mistakes on Lacan’s wilful obscurity. 1. See Freud’s essay The Loss of Reality in Neurosis and Psychosis, in his Collected papers, vol.1 1. 2. Wilden says in his essay Lacan and the Discourse of the Other that instinct (Trieb) is ‘always a psychic entity for Freud’ (The Language of the Self, p. 198). Yet in 1905 Freud was writing ‘The concept of instinct is thus one of those lying on the frontier between the mental and the physical’ (On Sexuality, p. 83), and in 1940 that instincts ‘represent the somatic demands on the mind’ (An Outline of Psychoanalysis, p. 5). There is no reason to suppose he ever deviated from such a view, and the whole of his paper Instincts and their Vicissitudes (1915, in Collected Papers, vol. IV) is premised upon it. 3. From The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis, in Merits, p. 38. 4. See for example the opening of David Macey’s review in Ideology and Consciousness, no. 4. 5. The function and field of speech and language in psychoanalysis. See Ecrits, pp. 51 (for ‘science of the particular’), 57 (for psychoanalysis as not yet a science), 72 (for reference to Plato), and 74 (for ‘conjectural science’). 6. ‘Displacement’ is the transfer of an emotive charge from one idea to another which is associated with it, without any real connection, e.g. Freud’s patient ‘the Rat-man’ indulged in compulsive slimming behaviour when he wanted to get rid of his English cousin Dick, whom he saw as a sexual rival – ‘dick’ being the German word for ‘fat’. According to Anika Lemaire, ‘For modern linguistics, metonymy is based upon the substitution of signifiers between which there is a relation of contiguity, of contextual connection. Thus in the example “thirty sail”, sail is put in place of boat.’ (Jacques Lacan, p. 93) 7. See Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics. Also Jonathan Culler’s Saussure – a short introduction, drawing comparisons with Freud and Durkheim. Both books published in Fontana paperbacks. 8. Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, Letters from inside the Italian Communist Party to Louis Althusser, pp. 169–170. 9. The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, pp. 63–4. 10. ‘Ego’ = the part of the self which includes the conscious, and which is connected to perception, speech and action. It alone is capable of logical thinking and reality-testing, and has the function of mediating between the demands of the instincts and the realities of the world in which they can be satisfied. ‘Super-ego’ = conscience in a repressive sense – the voice of the internalised father, with that of later figures of authority superimposed on it. It functions as an ‘internal saboteur’, like the little vicar in Woody Allen’s film Everything you wanted to know about sex ... Some wit has dubbed it: the part of the psyche that is soluble in alcohol. ‘Id’ = part of the self composed of unconscious wishes which are the representatives of the instincts, but are mostly repressed and ‘infantile’, and often mutually contradictory. 11. Perhaps the most striking proof of the effectivity of unconscious ideas occurs in Freud and Breuer’s Studies in Hysteria; a part of the body, such as an arm or leg, might be paralysed – a part that is that corresponds to our idea of a limb, rather than to a neuro-physiological system. On the nature of the unconscious as ‘the infantile’, see Freud’s exposition of his theories to ‘the Rat-man’ (Collected Papers, vol. III, pp. 314–5) where he uses the analogy of objects buried in Pompeii, which were subjected to change only after being dug up. 12. From the Complete Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 544. Lacan objects to the English translation of Freud’s ‘Wo es war, soll Ich werden’ by ‘Where id was there ego shall be’ (and also the French ‘le moi doit deloger le ça’). But while it is true that ‘es’ and ‘Ich’ are the ordinary German words for ‘it’ and ‘I’, not ugly Latinisms like their ‘English’ translations, it is perfectly clear in context that Freud intends them to be taken in their technical sense. For Lacan’s criticisms, see The Freudian thing, in Merits, pp. 128–9. 13. Quoted in Isaac Deutscher in The Prophet Unarmed, pp. 196–7. 14. Though Lacan is on occasion very scathing about anti-intellectualist tendencies in psychoanalysis, and should therefore not be simply equated with the people I am describing here. See for instance the last two paragraphs of the second section of ‘The agency of the letter in the unconscious’, (Ecrits, p. 171). Yet there are undisguised irrationalist elements in his work. 15. Merits, p. viii. For Lacan’s own account of desire, see for instance the final section of The direction of the treatment and the principles of its power, and The signification of the phallus – both in Merits. 16. Lacan roundly condemns ‘Americans’ who ‘reduce’ psychoanalysis to a means of obtaining ‘success’ or ‘happiness’ – see The Freudian thing, Ecrits, p. 127. Europeans, I suppose, consult analysts in order to obtain failure and misery. 17. Lacan is quite rude about existentialism in his paper The mirror stage (see Ecrits, p. 6). Yet the theory of ‘the F’ in that paper is much closer to that in Sartre’s The Transcendence of the Ego than to anything in Freud. They also have the same idea of the subject as a lack, and of desire as a purely inter-subjective phenomenon rather than an instinctual one, and as inherently un-satisfiable. In my book on R.D. Laing I argued that Laing was more Freudian and less Sartrean than is commonly thought; the reverse is true of Lacan. 18. Strictly speaking, Freud says this of instinct, not of desire. But desires are psychic representatives of instincts, and instincts operate within the psyche only though their representatives. 19. In his lecture The deconstruction of the drive, in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis – see especially pp. 165–6. 20. ‘Hunger is hunger’, says Marx, ‘but the hunger gratified by cooked meat eaten with a knife and fork is a different hunger from that which bolts down raw meat with the aid of hand, nail and tooth.’ A similar relation holds between sexual desires and sexual instinct. 21. He is quoted in the Magazine Litteraire as having said: ‘there is no such thing as progress. Everything one gains on one side, one loses on the other’. 22. In Lenin and Philosophy. 23. See the last two paragraphs of Althusser’s essay Freud and Lacan. 24. Engels says approvingly of Fourier: ‘He was the first to declare that in any given society the degree of woman’s emancipation is the natural measure of the general emancipation’ (Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Selected Works, p. 406), and states that ‘The predominance of the man in marriage is simply a consequence of his economic predominance, and will vanish with it automatically’ (Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Selected Works, p. 517). 25. For people who believe that Russia or China is socialist, there is a problem of explaining why women are still oppressed in those countries. 26. See for example the quotation from the manifesto of the French feminist group Psychanalyse et Politique, in Mitchell’s Psychoanalysis and Feminism, with its allusions to ‘historical and dialectical materialism (Marx, Lenin, Mao)’ and ‘psychoanalysis (Freud, Lacan)’; also the long article Psychology, ideology and the human subject, in Ideology and Consciousness, no. 1. In the latter, it is suggested that the absence of a cultural revolution in Russia, and Stalin’s ‘economism’ were responsible for what went wrong there; this is an odd position, when one recalls that Stalin billed his Great Purge as a cultural revolution, and that is presumably where Mao got the concept from. 27. E.g. Marx’s statement that the workers ‘have no ideals to realise, but to set free the elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society itself is pregnant.’ (Civil War in France, Selected Works, p. 295), or Trotsky’s that ‘Socialism does not aim at creating a socialist psychology as a pre-requisite to socialism, but at creating socialist conditions of life as a pre-requisite to socialist psychology’ (Results and Prospects, in The Permanent Revolution, p. 99). On sexual matters, Engels refuses to speculate about the practice of future societies on the grounds that once the socio-economic subordination of women is abolished, people ‘will not care about what we today think they should do’ (Origin of the Family, Selected Works, p. 517) – a forbearance which contrasts favourably with the Utopian moralism of the ‘cultural revolutionaries’ (e.g. Kollantai’s ‘new communist sexual morality’ of subordinating all personal relationships to the needs of the ‘work-collective’). 28. See Fred Halliday, Marxist analysis and post-revolutionary China, in New Left Review 100, pp. 171–2. 29. See his letter to Putnam: ‘I believe that your complaint that we are not able to compensate our neurotic patients for giving up their illness is quite justified. But it seems to me that this is not the fault of therapy but rather of social institutions ... the recognition of our therapeutic limitations reinforces our determination to change other social factors so that men and women shall no longer be forced into hopeless situations.’ (Letters between Putnam and Freud, pp. 90–1) 30. And it is to socialism that Freud is referring here (Civilisation and its Discontents, p. 80). He goes on to accuse socialists of an ‘idealistic misconception of human nature’ – a charge about which we have no grounds for complacency. 31. Despite this Lacanian tendency to eternalise socially specific features of the unconscious, Mitchell’s book is probably the best Marxist work on psychoanalysis since Reich left politics for rain-making. 32. ‘Material’, not merely ‘economic’. See Lenin’s defence of Marxism against Mikhailovsky’s criticisms: ‘Secondly – argues our philosopher – procreation is not an economic factor. But where have you read in the works of Marx or Engels that they necessarily spoke of economic materialism? When they described their world outlook they called it simply materialism ... Are you telling babes and sucklings, Mr. Mikhailovsky, that procreation has physiological roots!? Who do you think you are fooling?’ (Collected Works, vol. 1, p. 151) Top of page ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive Last updated on 6.7.2013