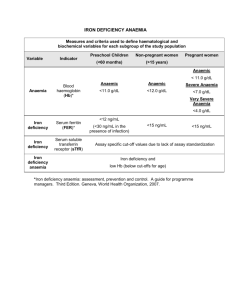

Technical Instruction Series No. HD/FH/01/2000 Revision 02/November 2001 Prevention and Treatment of Iron-Deficiency Anaemia I. PURPOSE: To redefine the strategy and provide guidelines for prevention and treatment of iron-deficiency anaemia among children 6-24 months of age and pregnant women. II. REVISION: This technical instruction supersedes the previous revision dated June 2000 of the Technical Instruction Series No. HD/FH/01/2000 III. EFFECTIVE DATE: June 2002 IV. APPLICABILITY: Applicable in all Fields of UNRWA's area of operations. V. INTRODUCTION: Iron deficiency is the most common form of malnutrition in the world. Iron deficiency anaemia is a problem of public health significance, given its impact on psychological and physical development, behaviour and work performance. It is most prevalent in children (6-24 months) and women of reproductive age, but is often found in older children and adolescents, especially girls, and may be found in adult men and elderly. Nutrition surveys conducted among the Palestine refugees in 1961, 1978 and 1984 revealed that more than 50 per cent of preschool children and women in reproductive age suffer from iron deficiency anaemia. In 1990, a nutrition survey was conducted by the WHO Collaborating Center at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta in four Fields of UNRWA's area of operations, namely Jordan, the Syrian Arab Republic (SAR), Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The survey revealed that the prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia among pregnant women ranged between 31.3% in the first trimester and 58.9% in the third trimester Agency-wide, while the prevalence among children 6-36 months of age ranged between 57.8% in the West Bank and 75.3% in SAR. A new intervention strategy for iron supplementation was then introduced in 1991, which was amended in 1995 placing special emphasis on treatment. VI. THE CURRENT STATUS OF ANAEMIA AMONG REFUGEE WOMEN AND CHILDREN In 1998, UNRWA conducted a study to assess the quality of child health care which revealed that the prevalence of anaemia among children 0-3 years of age was 35.9% in Jordan, 49.7% in the West Bank, 74.9% in Gaza, 29.6% in Lebanon and 28.0% in Syria. Also in October 1998, the WHO Collaborating Centre at CDC conducted a nutritional survey in Gaza Strip, the results of which revealed that iron-deficiency anaemia was still high among high-risk groups, namely infants, preschool children and pregnant women. In 1999, UNRWA conducted a study to assess the maternal health programme which revealed inter-alia that the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women was 44.7% in Gaza, 35.5% in the West Bank, 32.1% in Jordan, 28.6% in Lebanon and 27% in Syria. In addition, the study showed that the prevalence of anaemia progressively increases during the course of pregnancy as well as with parity. Anaemia below 9g/dL constituted 1.4% of pregnant women. This suggests that in spite of the interventions that the Agency had, so far, undertaken, iron-deficiency anaemia, still represents a major public health problem. VII. ETIOLOGY OF IRON-DEFICIENCY ANAEMIA: Body iron can be considered as having two main components, functional iron and storage iron. The functional component is found largely in the circulating haemoglobin. The storage component is found as ferritin and haemosiderin in the liver, spleen and bone marrow. A deficiency of iron in the functional component does not occur until stores are exhausted. Iron stores diminish due to imbalance between iron absorption and the body's needs. Such an imbalance can arise from:(1) (2) (3) Low iron intake, Inadequate absorption/utilization of ingested iron, Increased demand. A dietary intake of iron is needed to replace iron lost in the stools and urine, through the skin and in menstrual blood (women of reproductive age). In pregnancy, additional iron is required for the foetus, the placenta and the increased maternal blood volume. Demand is increased in case of growth, blood loss related to menstruation and bleeding, childbirth and chronic parasitic infestations. Infants, children and adolescents require iron for expanding their red cell mass and growing body tissue. Iron requirements for infants and children are lower than that for adults. But since they have lower total energy requirements than adults, they eat less and are at greater risk of developing iron deficiency, especially if their dietary iron is of low bioavailability. Childbearing patterns with short birth intervals, parasitic infestation and dietary factors all play a role in iron-deficiency anaemia. VIII. CONSEQUENCES OF IRON DEFICIENCY: Iron deficiency generally develops slowly and is not clinically apparent until anaemia is severe though deficiency in functional iron exists. Where iron-deficiency anaemia is prevalent, the following are the consequences on the different target groups: a) Infants and children: impaired motor development and coordination; impaired language development and scholastic achievement; psychological and behavioural effects (inattention, fatigue, insecurity, etc..); - decreased physical activity. - b) Adolescents: impaired cognitive development (i.e IQ loss); impaired scholastic achievement, decreased work capacity productivity; - in addition, in girls, decreased iron storage for later pregnancies. - c) d) IX. and Adults: decreased physical work and earning capacity; decreased resistance to fatigue. Pregnant women: - increased maternal morbidity and mortality; - increased foetal morbidity and mortality; - increased risk of low birth weight; - increased intrauterine growth retardation; - increased peri-natal mortality; - increased morbidity from infectious diseases. OBJECTIVES: The objectives of the Agency's programme for prevention and treatment of irondeficiency anaemia are: 1. To reduce morbidity and mortality from iron-deficiency anaemia among women of reproductive age by providing prophylactic iron supplementation during pregnancy and the post-partum period. 2. To provide iron therapy to pregnant women and children 6-24 months of age who suffer from moderate to severe anaemia. X. DEFINITIONS: Nutritional anaemia refers to a condition in which the haemoglobin content of the blood is lower than normal as a result of a deficiency of one or more essential nutrients (usually iron, folate or vitamin B12). The prevailing type of anaemia among the Palestine refugee population is iron-deficiency anaemia. Iron-deficiency anaemia is diagnosed by measuring the haemoglobin concentration. Other tests that measure iron stores such as serum ferritin and transferrin saturation are of little clinical significance. The following table shows the cut-off points of haemoglobin and haematocrit below levels which anaemia is defined for each target group: Age or Sex group Haemoglobin level Haematocrit level Below Below (g/dL) (%) Children 6 months-3 years 11 33 Pregnant women 11 33 Nursing mothers 12 36 The following cutoff points of haemoglobin levels are normally considered for defining the severity of anaemia: Severity of anaemia Mild Moderate Severe XI. STRATEGY FOR PREVENTION DEFICIENCY ANAEMIA Haemoglobin level 10.9 - 10.0 g/dL 9.9 - 7.0 g/dL Below 7.0 g/dL AND TREATMENT OF IRON- WHO advocates the following four basic approaches for the prevention and treatment of iron-deficiency anaemia: 1. 2. 3. 4. Supplementation with iron preparations. Dietary change and diversification to increase iron intake. Fortification of a suitable staple food with iron. Fostering public health measures. None of these strategic approaches is exclusive to the others, rather they are complementary. 1. IRON SUPPLEMENTATION: In principle all pregnant women under supervision at UNRWA maternal and child health care services should receive prophylactic iron supplementation. Those identified to be suffering from moderate or severe anaemia should receive treatment as outlined below: 1.1 Prophylactic Supplementation: The high physiological requirement for iron in pregnancy is difficult to meet with most diets. Therefore, pregnant women should routinely receive iron supplementation, which should continue for three months post-partum according to the table below to enable them acquire adequate iron stores. Guidelines for iron Supplementation to Pregnant Women 1.2. Dosage Duration 60 mg iron + 400µg of folic acid daily At first antenatal visit, throughout pregnancy and continuing 3 months postpartum. Treatment of anaemia: Severe anaemia is defined if haemoglobin is below 7g/dL or haematocrit below 20%. Clinically, it is defined as a low haemoglobin leading to the point that the heart cannot maintain adequate circulation of the blood. A common complaint is that the individuals feel breathless at rest. Although severe anaemia usually comprises a small proportion of the cases of iron deficiency anaemia in a population but may cause a large proportion of the severe morbidity and mortality related to iron deficiency. Severe anaemia may be clinically detected by assessment of pallor. The sites that should be examined include the inferior conjunctiva of the eye, the nail beds and the palms. This method will detect most but not all people who are truly severely anaemic. It is therefore, essential that the clinical assessment be completed by laboratory confirmation. It is important that UNRWA Medical Officers be able to recognize these cases and treat or refer individuals with severe anaemia. The training and supervision of this activity in primary health care settings becomes a priority activity when the prevalence of severe anaemia in population groups (e.g. pregnant women) exceeds 2%. For the purpose of this instruction series, the cutoff point for treatment of anaemia has been established at the level of haemoglobin value less than 10g/dl in order to detect and treat individuals suffering from moderate anaemia before they develop the complications of severe anaemia. Women and children with haemoglobin level less than 10g/dl should receive iron treatment according to the guidelines outlined in the table below: Guidelines for oral iron and folate therapy to treat anaemia Age Group Children 6-24 months Pregnant women Dosage Duration 25 mg iron daily 3 months 3 months 120mg iron + 400-800µg of folic acid daily § Note: After completing 3 months of therapeutic supplementation, pregnant women should continue the preventive supplementation regimen. 1.3 Frequency of haemoglobin measurement:(A) Pregnant women: § Screen all pregnant women, at time of first registration and at 24 weeks of gestation. (B) § Nursing mothers: Nursing mothers need not to be screened for anaemia. Only women who have had any of the following risk factors should be referred for haemoglobin testing: - Anaemic before delivery. - Ante-partum haemorrhage. - Post-partum haemorrhage. - Multiple births. (C) Children: At the age of 6 months, assess infants, who have one or more of the following risk factors, for anaemia: - Pre-term or low birth weight. Growth-retardation. Special care needs such as: chronic infection, inflammatory disorders, restricted diets, or extensive blood loss from wound, accident or surgery. Screen all children at the age of 12 months for anaemia as a routine measure using the haemoglobin concentration test. 1.4 Follow-up and referral of cases: a) Repeat the haemoglobin testing after one month from initiating the treatment. If Hb concentration improves, reinforce dietary counselling, continue iron treatment for 2 more months, then recheck Hb concentration. Reassess Hb concentration approximately 6 months after successful treatment is completed. b) If after one month the anaemia did not respond to iron treatment despite compliance with the iron supplementation regimen and the absence of acute illness, further evaluate the anaemia by using other laboratory tests, including CBC, MCV, MCH and sickling test. c) The following individuals should be referred to the specialist/ hospital for thorough investigation and appropriate management: - Pregnant women beyond 36 weeks of gestation with haemoglobin level below 9g/dL. Individuals with signs of respiratory distress or cardiac abnormalities (e.g. laboured breathing at rest or oedema). Anaemic patients with severe or moderate anaemia who did not respond to one month of treatment despite compliance with the iron supplementation regimen and further evaluation by using laboratory tests were abnormal. 2. DIETARY DIVERSIFICATION: 2.1 General principles: Although iron supplementation is the most rapid intervention, yet it is not the only and most important measure to control anaemia and increase haemoglobin concentration. The utilization of the most abundant form of iron in food is strongly influenced by enhancer and inhibitor food components in the diet. The modification of the behaviour leading to better selection or preparation of food so as to enhance intake or bioavailability of iron is the primary goal of this approach, to be complemented by other measures to improve the iron status of the population. The main principles of dietary diversification are: a) Increase consumption of iron-rich foods, particularly meats and other sources of haem-iron; b) Change meal composition to decrease the intake of inhibitors of iron absorption and to increase vitamin C-rich foods in meals that contain iron-rich food; c) Avoid the consumption of fresh cow's milk by infants and toddlers; and d) Promote food processing that destroys phytate or that reduces fiber content such as fermentation and cooking. 2.2 Enhancers of iron absorption: • Meat in its all forms: red meat, poultry, fish or seafood; • Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) which is present in fruits juices (orange or lemon), potatoes, and other vegetables (green leaves, cauliflower, cabbage, spinach, tomatoes, etc.). Many of these vitamin C-containing products also have vitamin A activity (which improves iron status although the mechanism is not exactly known); 2.3 Inhibitors of iron absorption: • Tannins, which are iron-binding compounds and most potent inhibitors of iron absorption, are present in tea, coffee, cocoa, certain spices and some vegetables. • Phytates present in cereal bran, cereal grains, high extraction flour, legumes, nuts and seeds. • Calcium in different forms; milk and milk products. The ultimate absorption and utilization, called "bioavailability", of iron depends on the balance between inhibitors and enhancers in a meal. For the effect of inhibitors or enhancers to occur, they have to be consumed with the meal. For example, if orange juice is taken 1 hour before or 2 hours after a meal, it has minimal impact on the absorption of iron from that meal. The same is true with an inhibitor, tea for example. 2.4 Guidelines for child feeding: • Encourage exclusive breast-feeding of infants (without supplementary liquid, formula, or food) for 4-6 months after birth. • Guide mothers not to offer bread or unfortified biscuits, between meals to their children as a means to keep them quiet. • Infants should not be given tea. If tea is to be served it has to be light and be given 2 hours after meals, it should not be given with meals or immediately after. • Encourage breast-feeding up to the age of two years. In case breast feeding is not possible for compelling reasons, use iron-fortified infant formula for any milk-based part of the diet and discourage use of low-iron milks (e.g. cow's milk, goat's milk, and soy milk) until age 12 months. • Encourage mothers to cook a mix of 100 grams of meat (or chicken) with seasonal vegetables (beans, peas, green onions, okra, tomatoes, etc.), potatoes and rice or wheat as an alternative to baby cereal. Strain the mix for babies 4<6 months, mash them for babies 6-8 months and pound them for infants 9-11 months. At 12 months give the child family food. • By approximately the age of 6 months, encourage one meal per day of foods rich in vitamin C (e.g. fruits, vegetables, or juice) to improve iron absorption, preferably with meals. • Guide mothers to introduce plain, pureed meats after the age of 6 months. 2.5 Examples of simple but very effective actions: • Separate tea drinking from mealtime. One or two hours later, the tea will not inhibit iron absorption since some of the food will have left the stomach. 2. • Add orange, lemon or fruit juice or other sources of ascorbic acid to the meal. Consume potatoes, cabbage, carrots, and cauliflower with meals. • Take milk or cheese as a between-meal snack. This will provide adequate calcium, without hampering iron absorption. FOOD FORTIFICATION: The countries of the region have undertaken to fortify bread with iron. WHO estimates that fortification of a staple food with iron could meet approximately 60 per cent of the daily requirements of iron. Whenever iron fortified foods are available, these are important additions to the diet. It must be noted however, that fortified bread and cereals are for the prevention of anaemia, not for its cure. 4. PUBLIC HEALTH MEASURES: Public health measures represent an essential component of the programme for prevention and treatment of iron-deficiency control programme. They comprise: a. Promotion of breast-feeding, as the mother's milk contains highly bioavailable iron that helps to restore iron storage in the child’s body and protect him/her from infection. b. Reducing the burden of intestinal infestations by the single dose of mebendazol 500 mg. If the affected person is a pregnant woman, delay the anti-helmenthic treatment until after delivery. c. Expansion of family planning services, including child spacing and improvement of the nutritional status of women. d. Fostering measures that decrease the frequency of infection, e.g. improved sanitation, sustaining high immunization coverage, home management of diarrhoeal diseases, etc. XII. COUNSELLING 1. Supplementation with iron preparations should be provided to the target groups only after individual or group counselling on the importance of compliance with the duration and dose of iron intake, as well as, on the importance of observing appropriate food habits. 2. Concentrated efforts should be exerted by all health staff to change the attitudes of the target groups towards factors known to influence the nutritional adequacy of iron in the usual diet of the population, e. g. certain weaning practices such as timely introduction of weaning foods that enhance iron absorption, separating tea drinking from meal time, etc. 3. Medical and nursing staff should ensure that iron supplements are issued, whether for preventive or therapeutic use, only after counselling of clients on: • • • • Types of iron-rich foods. Enhancers of iron absorption. Inhibitors of iron absorption Iron deficiency is not a "disease" that could be treated by a shortcourse of "medication". • Iron deficiency will recur unless additional measures are taken to improve dietary iron intake. • Nutritional adequacy of iron is important to prevent potential developmental delays in children, poor stamina and undesirable outcomes of pregnancy. XIII. RECORDING AND REPORTING 1. Child Health Record (Catalogue Numbers 06.7.696.1 for boys, and 06.7.698.1 for girls). Dates and results of haemoglobin concentration tests should be recorded on the second page of the record. 2. Maternal Health Record (Catalogue Number 06.7.650.1) Dates and results of haemoglobin concentration tests should be recorded in the relevant of the Ante-Natal Record. XIV. LEVELS OF RESPONSIBILTY 1) At Headquarters level: The Chief, Family Health is responsible for providing technical advice on implementation, planning, supervision, evaluation, staff training and health services research relevant to the strategy in close coordination with Chief, Disease Prevention and Control. 2) At Field level: a. The Field Family Health Officer (FFHO) is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the strategy in the Field to which assigned and training of health personnel in close coordination with the Field Disease Control Officer and Field Nursing Officer. b. The Laboratory Superintendent should maintain a system of quality assurance of testes performed at the health centre laboratory. c. The FFHO coordinates with the Education Department the health education activities in respect of iron-deficiency anaemia and the deworming programme at schools. c. 3) The Field Pharmacist orders, receives and ensures safe storage and distribution of the laboratory supplies and the iron and folate medications. At health centre level: a. The SMO/MO i/c is responsible for organization and in-service training of health centre staff on all aspects of the strategy, follow-up and reporting on all aspects relevant to the implementation of the programme and ensuring the continued availability of supplies pertaining to the programme. b. The Medical Officer in charge of MCH is responsible for implementing all aspects of the strategy including, identifying persons with moderate to severe anaemia, referring them to the laboratory for testing and taking action to treat them, as well as, to ensure that every mother and every pregnant woman receives adequate counselling before prescribing the iron supplementation. c. The Gyn/Obs. is responsible for thorough investigation and advice on the management of women with severe uncontrolled anaemia, as well as, on providing feed-back to the Medical Officer in charge of MCH. d. The Senior Staff Nurse should ensure that nursing staff are adequately trained on all aspects of the strategy and provide proper counselling to mothers and pregnant women. XIV. MONITORING AND EVALUATION 1. The prevalence of anaemia among children and pregnant women cared for by UNRWA, will be estimated annually by review of a representative sample of maternal and child health records based on the rapid assessment technique. 2. Periodic qualitative and quantitative surveys will be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of this strategy at reasonable intervals. Dr. Fathi Mousa Director of Health November 2001 FM/NJ(ironanaemiafinal) REFERENCES 1. Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR 1998; 47 (No. RR-3). 2. Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anaemia through primary health care, World Health Organization, 1989. 3. Guidelines for the control of iron deficiency in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and North Africa. WHO document No. WHOEM/NUT/177, E/G/11.96, 1996. 4. Fortification of flour with iron in the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and North Africa. WHO document No. WHOEM/NUT/202/E/G, 1998. 5. 6. Weaning from breast milk to family food, WHO/UNICEF, 1998. Guidelines for the use of iron supplements to prevent and treat iron deficiency anaemia, INACG/WHO/UNICEF, 1998. Iron-anaemiafinal