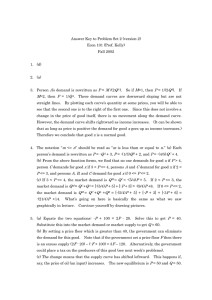

CHAPTER THREE AGGREGATE DEMAND IN CLOSED ECONOMY 3.1. Introduction Note: using expenditure approach of measuring GDP is given by: (1) Y= C+I+G+GX In a closed economy, NX=0 and GDP is given by the identity: (2) Y= C+I+G According to the national income identity, the income households receive (Y) = Total output of the economy (Y) = Total expenditure of all economic agents. Consumption: For simplicity, households require only to pay taxes (T) to left with their net income (Y-T), called Disposable Income. Y-T= C+S (Keynesian) consumption function (CF). (3) C= C0+c1(Y-T), Where c1=d C/ d(Y-T), 0<c1<1, showing a positive relationship between C&Y. c1 = slope of CF, or MPC, measures a one unit change in income brings c1 unit change in consumption. It is assumed constant (although varies among different income levels, countries, etc, .) C0 = autonomous consumption, unrelated to income; an intercept of CF. 1 Average Propensity to Consume (APC): C c (Y T ) C C 0 1 c1 0 Y T Y T Y T Equation (4) shows, APC changes with changes in income or disposable income. (4) APC APC is the slope of a curve that starts from the origin and crosses the consumption function at any given level of income. According to the equation, as income increases; saving will increase with a larger fraction of income. Fig 3.1: Consumption Function C C C0 c1 (Y T ) APC c1 C0 Y T Y HH saving is the difference between disposable income and consumption. (5) S = (Y-T)-[C0+C1(Y-T)] = -C0+(1-c1)(Y-T) MPS is given by: MPS = d S /d(Y-T) = 1-MPC APS is given by (6) APS = [Y-T]-[C0-c1(Y-T)]/(Y-T)= (1-c1) –C0/(Y-T) (2) Investment: Investments are often made by firms. Firms purchase new houses, buy investment goods to add to their stock of capital, replace existing worn-out machinery and equipment or change their inventories. Thus, investment includes these different types of spending. Investment is made for profit and thus it has its own opportunity cost. Firms consider the prevailing interest rate as an opportunity cost before they make investment decisions. In other words, if they have financial capital in their hands, they would observe, for instance, the 2 bank interest rate and make a decision whether putting this money in the bank and get interest or invest it would provide better returns. If they do not have money, they would consider the bank lending interest rate before they get credit for investment, calculate cost of capital and compare it with its return from the investment. Thus, investment function of households is given by (7) I (r ) , r (i ) Where r is real interest rate, i nominal interest rate and π is inflation rate. Nominal interest rate is the market or reported interest rate that investors or borrowers pay for the lender and real interest rate is the nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation. (3) Government expenditure (G): Government expenditure is of two types: (a) Goods and services for capital investment or recurrent consumption by the federal and local government agencies and (b) transfer payments to households such as welfare for the poor and social security payments (including pension) for the elderly. Government will have a balanced budget if its purchases or spending equals net tax or tax minus transfer payments: (8) G (T TR ) If G (T TR ) , government runs budget deficit and if G (T TR ) , it runs budget surplus. Transfer payments increase disposable income and consumption contrary to taxes. For simplicity, for the time being, we set T to stand for taxes less government transfer payments. Assume government spending ( G G ), private investment ( I I ) and taxes ( T T ); AD or E is given by: (9) E c0 c1 (Y T ) I G Aggregate Demand, total demand for goods and services in the economy, is determined by the interaction between product (goods) and money markets. This interaction of the product and money market, it is represented by IS-LM. The product market equilibrium is designated by the IS curve; where I and S stand for investment and saving respectively. 3 Money market equilibrium is captured by the LM curve. L and M stand for liquidity and money respectively. We will discuss the two markets separately. 3.2. The Product/Goods Market Equilibrium First step use the Keynesian cross to assess the possible actions of firms when there is disequilibrium in the product market. Disequilibrium occurs when planned expenditure and actual expenditure are not equal. Actual expenditure is the amount that households, firms and government actually spend on goods and services. Planned expenditure is the amount that households, firms and government would like to spend on goods and services. Planned expenditure is given by Equation (9) or displayed by Figure 3.2. Planned expenditure increases less proportionately with an increase in income. Figure 3.2: Planned Expenditure as a Function of Income Planned Expenditure, E E c0 c1 (Y T ) I G MPC= c1 Birr 1 Income, Output, Y On the supply side, for simplicity, we leave what determines the level of output supplied and simply consider the total supply in the economy ( Y ). 4 Fig 3.3: The Keynesian Cross Income (Y) Planned Expenditure, E E c0 c1 (Y T ) I G A E-Bar MPC= c1 Birr 1 450 Income, Output, Y Y-Bar The 450 line divides the quadrant into equal parts along which output equals actual expenditure. Product market equilibrium is at point A; Actual expenditure = Planned expenditure. No excess demand; no excess supply. If the economy is in disequilibrium, how could it get back to the equilibrium? Fig 3.4: Disequilibrium in the Product Market Actual Expenditure Planned Expenditure, E Y2 Planned Expenditure E2 E A E1 Y1 Income, Output, Y Y1 Y Y2 If the economy operates below point A towards the origin, planned expenditure ( E1 ) exceeds output ( Y1 ); firms draw down their inventories to satisfy the excess demand ( E1 Y1 ) . They 5 also employ more workers and expand output; a movement towards A (high output and AD). If the economy operates above point A, output (Y2 ) exceeds planned expenditure ( E2 ) ; firms pile-up inventories by the amount (Y2 E2 ) to reduce their sales to the level of AD, a movement towards A. Equilibrium condition: (10) Y 1 (c0 I G c1T ) E 1 c1 Government fiscal policies may affect the equilibrium condition in the economy. Before we consider changes in fiscal policy instruments, let us quantitatively indicate the The parameter 1 /(1 c1 ) is called multiplier; because it multiplies changes in exogenous variables such I or G to give resulting change in output. Income of HHs is allocated for (a) consumption, (b) saving and (c) taxes. (11) Y C S T (11) On the expenditure side, AD equals (12) Y C I G (12) At equilibrium, we have (13) (13) Y C S T C I G S T I G From Equation (13), (14) S I (G T ) If government has a balanced budget, G T , this equals (15) SI Equation (14) is called Saving-Investment Identity. If government runs a budget deficit or (G T ) 0 , 6 (16) S I Equation (16) shows that part of the saving is siphoned off to finance government budget deficit. It is called crowding out of private investment. Because of excess government spending, private investment is constrained. If government has a budget surplus, (G T ) 0 , then private investment exceeds saving. (17) SI Thus, private investment is finance by household saving ( S H ) and government saving ( S g ) , which is equal to government budget surplus. (18) I S H S G We have seen that an increase in “I”, “C” and “G” increases AD. What is the effect of saving on investment? In the short-run, increase in saving has contractionary or negative effect on output. An increase in saving requires C0 or c1 to decline or (1-c1)) to increase. Lowering C0 decreases AD by the amount C0/ (1-c1). A decrease in c1 reduces the multiplier and also has a stronger negative effect on AD. This is called the saving paradox or the Paradox of Thrift. In the short-run, there is an inverse relationship between AD and saving, because an increase in S given Y and T, comes by reducing C. In the long-run, as S increases, supply for loan-able funds increase; and interest rate falls. Decline in interest rate leads to an increase in I and also AD. The Effect of Fiscal Policy on AD: If government increases its spending G, (G 0) brings; (18) Y 1 (G ) 1 c1 7 1 where 1 1is government expenditure multiplier. Thus, the positive change in 1 c1 government spending raises planned expenditure by ( 1 /(1 c1 )G) for any given level of income. This leads to a move for the equilibrium position from A to B and income raises from Y1 to Y2 . Fig 3.5: The Effect of Increased in Government Spending on Equilibrium Output Y Planned Expenditure, E E2 B E2 E1 E1 A Income, Output, Y Y1 Y2 The multiplier increases as MPC ( c1 ) increases. If tax is reduced by T , disposable income increases by the change in tax and increase consumption by (c1T ) . Planned expenditure becomes higher for any given level of income (Y) and thus shifts the planned-expenditure schedule upward from point A to point B as in Fig 3.4. 1 Based on Equation (13), the multiplier is derived from the total effects of changes in government spending on income as follows. dY d c1 (Y T ) dI dG dY c1dY dG , because dI 0 and dT 0 (1 c1 )dY dG dY 1 dG (1 c1 ) 8 Output increases from Y1 to Y2 by the change in tax times the multiplier for the tax rate or c1 Y .T 2. (1 c1 ) Let I be endogenously determined in the model as: (19) (20) I (r ) , where r (i ) or (20) (21) I I br , where I is autonomous investment, independent of income and interest rate; b is the slope, measuring the responsiveness of investment to changes in interest rate. The investment function or schedule is shown in Fig 3.6a. The curve shifts upwards, other things remain the same, with the change in intercept or autonomous investment. We also assume that other components of the AD or planned expenditure are assumed constant or government is not using its fiscal policy instruments such as G and T. Given this assumption, investment (I) and real interest rate (r) are inversely related as discussed above. The change in interest rate affects investment and investment in turn affects planned expenditure or equilibrium level of output. Fig 3.6a, Fig 3.6b and Fig 3.6c capture (a) the relationship between r & I, (b) between r & E and (c) between r and Y respectively. Fig 3.6a shows that a decrease in interest rate from r1 to r2 motivates business entities to boost their demand for investment from I (r1 ) I1 to I (r2 ) I 2 , which leads to a change in the equilibrium position from point A to point B across the investment – interest curve and the Given Y c0 c1Y c1T I G A change in T with I and G being constant leads to dY c1dY c1dT dY c1dY c1dT (1 c1 )dY c1dT or dY / dT c1 /(1 c1 ) or tax multiplier. 2 9 increase in investment in turn causes an upward shift of planned expenditure curve from E1 to E2 and a change in the equilibrium position from A to B across the Keynesian cross, with higher level of output Y2 than Y1 . Because of an inverse relationship between interest rate and investment, which is the component of planned expenditure or AD, we observe an inverse relation between income or output with real interest rate. Thus, IS curve relates interest rate and income or output, and it is a downward sloping slope as indicated in Fig 3.6c. Fig 3.6b: Keynesian Cross Y E E2 B E2 Y2 E1 E1 Y1 A Fig 3.6a: Investment Function Y r Y1 r Y2 Fig 3.6c: IS Curve A r1 A B B B r2 I1 I (r ) Y I I2 Y1 Y2 What is the IS curve? IS curve (or schedule) shows the combinations of interest rate and output (income) such that planned spending equals income. The Effects of Fiscal Policy Change on Interest Rate and Income: If, for instance, government spending increases (∆G>0), AD or planned expenditure line shifts upwards in the Keynesian cross. Equilibrium output increases by ∆Y=[1/(1-c1)]*∆G); IS curve shifts upwards. The transmission mechanisms and the chain effects are seen in Fig 3.7a and 3.7b respectively. 10 Fig 3.7a: Keynesian Cross Expenditure, E Actual Expenditure E2 B Y2 E1 A Y1 3.7B: The IS Curve Fig Interest Rate 45 0 Income, Y Y1 Y2 B IS2 r A IS1 Income, Output, Y Y1 Y2 IS curve below is negatively slopped because a higher interest rate reduces investment and AD and equilibrium income. The slope of IS curve depends on sensitivity of investment to changes in r and also the multiplier. Relaxing the assumptions imposed on the multiplier: Normally, consumption is a function of disposable income, which is output (income) plus, given level of government transfer ( R ) less taxes (T). We assume government collects its tax revenue at a rate of t per a fraction of income (Y), where 0 t 1 . (21) C c0 c1 Y R (tY ) or or C c0 c1 R c1 (1 t )Y Incorporate new C and I functions in (21) to AD gives: 11 (22) (23) Y c0 c1 R c1 (1 t )Y I br G (1 c1 (1 t )Y c0 c1 R G I br If we collect autonomous spending together, we would get A br (23) (24) Y g [ A br ] 1 c1 (1 t ) 1 where A c0 c1 R I G and g (1 c1 (1 t ) Both equations (23) and (24) are called the IS Equations. The change in income due to a one unit change in interest rate is given us: (24) (25) Y b g b r 1 c1 (1 t ) The IS equation as normally depicted in mathematics is given by: ( Y g A ) br r A 1 Y b gb or r A Y [1 c(1 t )] b b IS represents a combination of interest rates and income levels at which the goods market clears or becomes in equilibrium. IS curve shows the negative association between AD and interest rate through investment function. The slope of IS curve is (25) (26) dr (1 / g b) dY The larger the multiplier ( g ), the smaller or flatter the slope of the IS curve becomes and the larger the effect of fiscal policy on income. Changes in the IS curve: An increase in autonomous spending (TR, I, G, C0), shift both planned aggregate spending and the IS curve. If government increases spending by ∆G and given multiplier G 1 1 1 c1 (1 t ) 1 c1 c1t Government spending change on output across the Keynesian cross or IS curve becomes: 12 (26) (27) Y G G (a) What would happen if the business entities change their autonomous investment spending? The effect of autonomous investment on income is similar to change in government spending. (27) (28) Y G I The introduction of the tax rate (t) reduced the size of the multiplier and thus the effect of government spending on income. (b) The effect of change in government transfer on aggregate output: c1 R 1 c1 (1 t ) Tax rate change on the multiplier and on income or output: (28) (29) Y c1R c1 (1 t )Y Y Two effects will arise: (a) direct effect on consumption spending and (b) induced effect because of change in income through change in the multiplier is: (29) The direct effect on consumption spending c1 (t )Y c1Y * t (30) Induced effect because of income change through multiplier c1 (1 t ' )Y c1Y Y c1Yt c1 (1 t ' )Y t 1 c1 (1 t ' ) Y c1Y t The change in output per unit tax rate cut ( ) t 1 c1 (1 t ' ) (31) (32) The change in tax rate affects the slope of the IS curve through the multiplier. If tax rate increase, total tax revenue collection could increase. However, this will reduce the multiplier g and thus steeper the IS curve; thus the change in autonomous spending brings lower amount of change in income. Expansionary fiscal policy instruments such as increased government spending and tax cut become more effective if the economy is in recession to let economy recover. When the economy is overheating, tax rates may increase or government may cut its spending to get back to equilibrium. 13 What will be the effect of change in government spending on government budget balance? The effect of change in G on income ( Y ) G G The effect of change in G on tax revenue T tY t g G (33) (34) The effect of change in G on government budget balance (GBB ) T G (t g G G ) (t g 1)G 3.3. The Money Market and the LM Curve Assets of an economy could be broadly classified into two categories; financial assets and tangible assets. Real assets or tangible assets are (a) properties owned by firms or corporations such as machines, land, and structures and buildings (b) consumer durables (such as cars, washing machines, stereos, etc.) and (c) residences owned by households. These assets are called real to distinguish them from financial assets (money, stocks and bonds).These assets carry a return that differs from one asset to another. Owner-occupied residences provide a return to owners who enjoy living in them and not paying monthly rent. However, they have opportunity costs. Machines of a firm produce output and thus make profits. Financial assets are money; bonds or credit market instruments (and other interest-bearing assets and equities or stocks. Bonds: A bond is a promise by a borrower to pay the lender a certain amount (the principal) at a specified date (the maturity date of the bond) and to pay a given amount of interest per year in the meantime. Bonds are issued by many types of borrowers such as governments, municipalities, and corporations. The interest rates on bonds issued by different borrowers reflect the differing risks of default. Default occurs when a borrower is unable to meet the commitment to pay interest or principal. 14 Perpetuity: It is a bond which promises to pay interest forever, but not to repay the principal on the bond. Treasury Bills: Promissory notes by a borrower/central bank to pay the lender the principal at a specified maturity date (often within 90 days) and interest. Equities or Stocks: Equities or stocks are claims to a share of the profits of an enterprise or organization. For example, a share in the Abyssinia Bank or Raya Brewery entitles the owner to a share of the profits of the bank or the factory. The shareholder, or stockholder, may receive the return on equity in two forms. (a) In the form of dividends: firms may pay regular dividends to their stockholders a certain amount for each share they own. (b) In the form of capital gains: When business enterprises become profitable, people will want to hold higher number of shares from this enterprise. When this occurs, the shares become more valuable since they now represent claims on the profits. Therefore, the price of the stock in the market will rise, and stockholders can make capital gains. A capital gain is an increase, per period of time, in the price of an asset. Return to stock = dividend +capital gain (c) Firms may also decide not to distribute profits to the stockholders but rather retain the profits and reinvest them by adding to the firms' stocks of machines and structures. This is called retained earnings. Money: It is the most convenient means of payment. What is money? Money is the stock of assets that can be readily used to make transactions and can be immediately used for payments. Money Functions: Medium of exchange: we use it to buy goods and services; 15 Store of value: transfers purchasing power from the present to the future and Unit of account: the common unit by which everyone and measures prices and values. Money Types a) Fiat money: This has no intrinsic value. It is nothing but the paper currency or cheque we use. b) Commodity Money: This has intrinsic value; for instance, silver, gold coins, etc. What does money stock constitute? There are two types of money stock. Based on composition, we have different components and deposits. Currency in Circulation: The fiat money and commodity money that we see circulating in the market. Demand Deposit: Demand deposit is non-interest bearing deposit; it can be transferred easily to bearer of the check. Saving Deposit: It is the common kind of deposits that we know, a deposit that bears interest but can be drawn at any time (depending sometimes on the amount). Time Deposit: It is interest bearing deposit, cannot be withdrawn from banks before the agreement set between the bank and the client. Following these components, we have three types of money 1. Narrow money (M1) (36) M1 = C + DD, where C = currency in circulation, DD = demand deposit. 2. Quasi Money: (37) SD +TD 16 SD = Saving deposits and DT = Time deposit 3. Broad money (M2) (38) M2 = M1 + SD + TD where SD = saving deposit, TD = time deposit, or M2= Narrow Money + Quasi Money The Demand for Money There are three motives for holding money. Precautionary demand for money Speculative demand for money Transaction demand for money (1) Precautionary Demand for Money: It is a demand for money kept aside for precautionary (for fear of risks) and it is affected by transaction and speculative demand for money. For simplicity, we assume precautionary demand for money is zero for the time being. (2) Speculative Demand for Money: A person can put his liquid assets into either bonds or money. An increase in interest rate, which is a return on bonds, induces to hold assets in the form of bond and hold less in the form of money. Such demand for money depends, therefore, on the cost of holding money – interest and called speculative demand for money. At low interest rate, the speculative balance increases while at higher interest rate the speculative balance declines. Thus, demand for money for speculative purposes is a negative function of interest rate. (39) LS l (r ), dLs 0 dr where Ls = speculative demand for money, l = liquidity preference, r = interest. 17 Fig 3.8: Speculative Demand for Money r L(r, Y1) L(r, Y0) M/P Figure 3.8 indicates that speculative demand for money is negatively related with interest rate and each curve is drawn with level of income or assume income to be fixed at a certain level. As income increases, the speculative demand for money increases for any given level of interest rate. This is shown by a shift in the speculative demand for money towards the right. Transaction Demand for Money: It is the motive for holding money to bridge the time gap between receipt of income and payments that have to be made for transaction purpose. The transaction demand for money increases with an increase in income. However, the transaction demand for money curve portrays the relationship between income and transaction demand for money assuming interest rate constant. (40) LT K (Y ), dLT 0 dY Fig 3.9: Transaction Demand for Money Y L (Y , r ) M/P The demand for money and also called the demand for real balances (sum of the two functions) is given by: (41) L = l (r ) + k (Y ) 18 The specific function of demand for real money balances is a decreasing function of interest rate. (42) L = kY - hr , k , h > 0. Real money balances (real balances) are the quantity of nominal money divided by the price level. It is money expressed in terms of the number of units of goods that the money will buy. Money Supply: It is to be exogenously determined by the central bank regardless of the interest rate (assumption). At equilibrium, money supply equals the demand for money. (43) M l (Y ) h(r ) P where M/P is real money supply and the other part of the equation is money demand. The specific functional form could become: (44) ( M / P) kY hr 1 r [ M / P kY ] h This is LM – equation representing equilibrium in the money market. The LM curve represents the pairs of interest and income that keep the money market in equilibrium with the given level of money supply, M, and a given price level P. It is derived as follows. Fig 3.10: Derivation of LM Curve r r E2 r2 LM E1 r1 L1 L2 Y M /P LM is positively sloped because an increase in Y raises the transaction demand for money and so of the total money demand. LM is drawn for constant money supply balances, while income 19 changes or increases. There is now excess demand in the money market at the initial interest rate ( r r1 ). Interest rate must rise to restore equilibrium in the money market at r r2 . The LM curve represents the pairs of interest and income that keep the money market in equilibrium with the given level of money supply, M and a given price level P. Fig 3.11: The Speculative and Transaction Demand and LM Curve r LM Ls h(r ) Y Ls M / P h(r ) k (Y ) LT k (Y ) LT The slope of the LM – curve is: (45) dr k 0 dY h LM curve is drawn by changing the income level for a given supply of real money balances. If National Bank (NB) changes the real money balances, the LM curve shifts. Suppose NB reduces nominal money supply from M1 to M2 and real income remain constant as Y . This leads to a fall in real money balances from M1/P to M2/P and shifts the real money supply curve towards the left. The reduction in the supply of real money balances creates scarcity in money circulated in the economy and people will have no option but reduce the speculative demand for money. Interest raises and a new equilibrium occurs in the money market in Figure 3.12 a. This leads to a shift in the LM curve upwards in Figure 3.12 b. If there is an increase in the supply of real money balances, there will be shift in the LM curve towards the right or downwards. 20 Fig 3.12a: Money Market Equilibrium Fig 3.12b: Shift in LM Curve in Response to Money Policy Changes LM 2 Interest rate, r Interest rate, r LM1 r2 r1 L = (r, Y ) Income, Y M2/P M1/P Y What determines the slope of the LM curve? The slope of the LM curve is given by dr / dy k / h in Equation (45). The greater the responsiveness of the demand for money to income as measured by k and/or the lower the responsiveness of the demand for money to the interest rate, h, the steeper or (the higher the slope of) the LM curve will be. If the demand for money is relatively insensitive to the interest rate or h is close to zero, the LM curve is nearly vertical. If the demand for money is very sensitive to the interest rate, so that h is large, then the LM curve is close to horizontal. In that case, a small change in the interest rate must be accompanied by a large change in the level of income in order to maintain money market equilibrium. What causes the LM curve to shift? The real money supply is held constant along the LM curve. It follows that a change in the real money supply will shift the LM curve. If the real money supply increases, which is represented by a rightward shift of the money supply schedule, the interest rate has to decline in order to restore money market equilibrium. This will lead to a rightward/downward shift in the LM curve. What happens on points where we are not on the LM curve? 21 Figure 3.13: Points on the LM Curve E2 Interest rate r2 r1 i LM E3 E1 E4 LT(Y1) LT (Y2) Y Income The money market is in equilibrium at point E1. Assume an increase in the level of income to Y2. This will raise the demand for real balances and shift the transaction demand curve for money to the right. At the initial interest rate (i1), therefore, the demand for real balances would be higher. On all points below and to the right of the LM curve, there is an excess demand for real balances. Conversely, points above and to the left of the LM schedule correspond to excess supply of real balances. 3.4. Short-Run Equilibrium in the Economy The Keynesian cross in the product market is the foundation for IS curve. The theory of liquidity preference as applied in the money market is the basis for LM. Goods Market: IS Money Market: LM Y C (Y R T ) I (r ) G M / P L( r , Y ) (46) (47) Fig 3.14: Equilibrium in the IS-Model Interest Rate, r Equilibrium Interest Rate, LM A r IS Income, Y 22 Y Equilibrium Income, Figure 3.13 represents a simultaneous equilibrium in both the product/goods market and the money market. The equilibrium is at point A, with interest rate ( r ) and income ( Y ). At this interest rate and income level, (a) the public holds the existing stocks of money and (b) planned spending equals output. On the IS curve, the demand for goods is equal to the level of output. On the LM curve, the demand for money equals the supply of money. The simultaneous equilibrium of the product and money market is maintained given constant government spending, taxes, government transfer, autonomous private investment spending, money supply and the price level for the time being. If there is a change in government expenditure, government transfer, private spending or tax, there will be a shift of the IS curve depending on the direction of change of these variables or policy instruments. On the other hand, if there is a change in money supply or price levels, this will affect the amount of real balances and thus shifts the LM curve. Because of a shift in IS, LM or both, there will a change in the equilibrium of level if interest rate and income or output. 3.4.1. Monetary and Fiscal Policy Analysis Using the IS-LM Framework This section examines how changes in policy and shocks to the economy can cause these curves to shift. Effect of Fiscal Policy Changes Changes in fiscal policy measure such as government spending or tax rates shift the IS Curve and change the short-run equilibrium in the two markets. Changes in Government Spending Suppose government has increased its purchases of goods and services by (ΔG). Planned expenditure (E) in the economy increases and the line for planned expenditure shifts upwards in the Keynesian cross. The increase in planned expenditure stimulates firms to increase their goods and services and this leads to an increase in income (Y). The change in income is the product of the multiplier and the change in government spending. 23 (a) If the model assumes taxes to be unrelated to income (or) ( T T ), then the multiplier would be g 1 /(1 c1 ) , where c1 MPC and the change in income becomes (48) Y 1 .G (1 c1 ) (b) If the model assumes taxes to a function of income (or) ( T tY ), then, the multiplier 1 becomes * g and change in income becomes changes in government 1 c1 (1 t ) spending multiplied by the multiplier as: 1 .G (49) Y 1 c1 (1 t ) The change in government spending causes a change in equilibrium income in the product market. This leads to a shift in the IS curve to the right by the change in government spending and the multiplier within given interest rate ( r1 ) to point B in Figure 3.15. However, this point will not ensure equilibrium in both markets immediately. Figure 3.15: Effect of Change Government Spending in the IS-LM Model Interest Rate, r LM C r2 iii A B r1 i IS2 IS1 ii Income, Y Y1 Y2 However, a shift in the IS curve with increased in the level of income will cause changes in the operation of the money market as well. The demand for money balances depends on income (transaction demand for money) and also interest rate. As income increases, the quantity of money demanded given interest rate increases although the supply of real money has not changed. This will create disequilibrium or imbalance in the money market, which causes for an 24 increase in interest rate to r2 . On the IS side, as interest rate rises, firms cut back their planned investment; thus reduce the total planned expenditure in the Keynesian cross and equilibrium level of income. The final equilibrium point in the IS-LM model becomes at point C. Thus, the fall in investment partially offsets the expansionary effect of the increase in government purchases. Note: (a) If we leave the LM curve for the time being and assume tax to be unrelated to income, then the change in income due to change in government spending would be: (50) Y 1 .G (1 c1 ) (b) If we leave the LM curve for the time being and assume that tax is related to income, then the change in income due to change in government spending would be: (51) Y 1 .G 1 c1 (1 t ) Thus, an increase in income (51) is lower than (52) because of change in the introduction of tax rate in the model. (c) If we introduce the LM or the money market, assume tax is related to income, investment is related to interest rate as I I br and then we have the following transmission mechanisms. G E Y Md r I E Y The change in government spending in scenario (c) brings lower change in income than both (a) and (b). The horizontal shift in the IS curve by amount (i) in Figure 3.15 equals the rise in equilibrium income in the Keynesian cross assuming that investment is unrelated to interest rate and larger than the increase in equilibrium income in the IS –LM model. This difference is explained by the crowding out of private investment by increased government expenditure, which is caused by the increase in interest rate. 25 Changes in Taxes Assume for simplicity that tax is not functionally related with the income level. Government wants to cut taxes by ( T ) from (T1 ) to (T2 ) . The tax cut increases the dispensable income of consumers and increases their planned consumption expenditure. This in turn leads to an upward shift in planned expenditure curve and leads to a change in equilibrium level of income in the Keynesian cross. This leads IS1 to shift towards the left, IS2 in Figure 3.15. Given interest rate, the IS curve horizontally shifts by the change in income ( Y ), which is the tax multiplier times c1 1 c1 and the change in tax ( T ). This is given by: c1 (52) Y .T 1 c1 ) Equilibrium in the economy moves from point A to point B, with higher level of income and the interest rate. As it was the case in government expenditure, an increase in income because of tax cut leads to increased demand for real money balances. Given real money balances, increased interest rate reduces planned investment expenditure, total planned expenditure and income on the Keynesian cross. Figure 3.16: The Effect of Change in Tax Interest Rate, r LM Tax cut shifts IS1 to IS2: at r r2 r1 , c Y 1 * T 1 c1 iii r1 IS2 IS1 ii Income, Y Y1 Y2 The overall effect of tax cut on income in the IS–LM model is smaller than it is in the case of the Keynesian cross, and it is Y2-Y1. 26 Monetary Policy Effects As indicated above, price level (P) is fixed in the short run. Suppose there is an increase in nominal money (M), which leads to an increase in real money balances M/P. For any given level of income, an increase in real money balances leads people to have more money than they want to hold at the prevailing interest rate. Interest rate falls until all the excess money vanishes. This leads to an increase in the demand for holding real money balances with new equilibrium in the money market. This leads to a downward shift in the LM curve from LM1 to LM2. The change in money market equilibrium also brings a change in the product market equilibrium. Lower interest rate stimulates planned investment, total planned expenditure and income Y. This brings a new equilibrium point from point A to point B at lower interest rate and higher level of income. This process is called the monetary transmission mechanism. Figure 3.17: The Effect of Real Money Supply Interest Rate, r LM1 LM2 A r1 B iii r2 C IS ii Y2 Income, Y Y1 The impact of the interaction between fiscal and monetary policies The effect of a change in one government policy (either fiscal or monetary) depends on whether or not other policies change and if so, what other specific policy change occurs. For instance, if government wants to increase tax, the impact on the economy depends on the 27 policy that the Central Bank pursues in response for the fiscal policy. Central Bank could (a) hold the money supply constant, (b) hold the interest rate constant or (c) maintain the level of income constant. Consequently, the equilibrium outcome of the increase in tax depends on which policy scenario that the Central Bank wants to pursue. (a) Suppose the Central Bank holds the money supply constant: Phase 1: The economy was at point A before the intervention. The tax increase shifts the IS curve to the left from IS1 to IS2 because of the fall in planned consumption expenditure, total planned expenditure and income. The fall in income reduces a fall in transaction demand and thus a fall in money demand. This leads to a fall in interest rate and an increase in planned investment expenditure and total planned expenditure; which consequently leads to an increase in the level of income. The phase 1 effect of reduction in income dominates the phase 2 effect of an increase in income. The equilibrium point will be at B. Thus, net effect of tax increase could lead to a recession with low interest rate ( r2 ) and low level of income ( Y2 ). Fig 3.18a: Effect of Tax Increase on Equilibrium (Holding Money Supply Constant) Interest Rate, r LM A r1 r2 B IS1 IS2 Income, Y Y2 Y1 (b) Suppose the Central Bank decides to maintain the interest rate constant ( r r1 ). We have already witnessed that when tax increases the IS curve shifts to the left from 28 IS1 to IS2 and causes a fall in equilibrium level of income and interest rate ( Y2 , r2 ) . To maintain the interest rate at its original level ( r r1 ), the Central Bank must decrease the money supply (M). This fall in the money supply shifts the LM curve upward and causes the level of interest to pick up to its original level; ( r r1 ). This brings a further decline in income. Thus, the fall in income because of the tax cut; as money supply varies to hold interest rate constant (scenario, b) is larger than the fall in income when the money supply is constant as in scenario (a) above. Fig 3.18b: Effect of Tax Increase on Equilibrium (Holding Interest Rate Constant) Interest Rate, r LM2 LM1 r1 C A r2 B IS1 IS2 Income, Y Y3 (c) Y2 Y1 Suppose the Central Bank wants income to remain at it is: If Central bank wants to prevent the tax increase from lowering income, it has to raise the money supply. This will lead households to hold excess money than demand and causes interest rate to fall. The LM curve shifts downwards to the extent that it offsets the effect of the shift in the IS curve to the left. In this scenario, income remains constant and the tax increase does not cause a recession, but it causes a fall in interest rate from r2 to r3 . A combination of fiscal policy (tax increase) and a monetary policy (increase in money supply) maintain income constant but change the allocation of the economy’s resources or the composition of planned expenditure. Higher taxes depress consumption, while lower interest rate stimulates 29 investment. Thus, the need to keep income constant causes a greater fall in interest rate and also the allocation of income away from consumption3. Fig 3.18c: Effect of Tax Increase on Equilibrium (Holding Income Constant) Interest Rate, r LM1 LM2 A r1 r2 B IS1 r3 IS2 Income, Y Y3 Y2 Y1 3.1.6. Aggregate Demand The above discussion of IS, LM and IS-LM has been based on the assumption that in the shortrun price level is fixed. To derive the aggregate demand curve, we relax the fixed price assumption and examine how IS and LM models shift to price changes. Suppose the money market equilibrium and overall equilibrium was at point A on Figure 3.19a, when P P1 . Suppose price increases from P1 to P2 , where P2 P1 . For any given money supply M, a higher price level P2 reduces the supply of real money balances from M P1 to M P2 . A lower supply of real money balances shifts the LM curve upward or to the left. This move raises the equilibrium interest rate from r1 to r2 and lowers the equilibrium level of income from Y1 to Y2 in Figure 3.20a. This implicit negative relationship between income and price level enables to draw aggregate demand (AD) curve and price in Figure 3.19b. AD curve shows the set of 3 This policy move prevents income from falling in the short-run. The fall in interest rate may depress the motivation of households to save in the long-run and constrain the amount of loanable funds for investment. 30 equilibrium points of income on the IS–LM model as the price level varies. It also shows the negative relationship between price and income. Figure 3.19: Derivation of AD Curve Price, P (a) Interest rate, r (b) LM2 B LM1 B A A AD IS Income, Y Income, Y Y2 Y2 Y1 Y1 A change in income in the IS–LM model resulted from a change in the price level represents a movement along the aggregate demand curve. What shifts the AD Curve? A change in income due to fiscal and monetary policy changes in the IS–LM model for a fixed price level shifts the AD curve in either way. Any expansionary policy (increase in government spending, increase in money supply and a decline in tax) brings an increase in income given price level and shifts the AD curve to the right and leads to higher level of income for given price level. Effects of Expansionary Fiscal and Monetary Policy on AD The Effect of Expansionary Monetary Policy on AD: As indicated above, the LM curve is drawn for given real money balances. Any change on real money balances (either because of change in money supply or price) will shift the LM curve. Suppose monetary authorities increase money supply given the price level. This intervention by government shifts the LM curve downwards or to the right from LM (P1) to LM (P2) in Panel (a) of Figure 3.20. This movement of the LM curve will create excess supply of real money balances over the demand in the economy. Given the equation, M / P l (Y ) h(r ) , an increase in real money balances, (M / P) , would cause or require a decline in interest rate ( r ) and thus an increase in the 31 demand for real money balances so as to bring back the money market to be at equilibrium. The money market changes will have an impact on the product or commodity market. The decline in interest rate will lead to a downward movement along the IS curve until we have a new equilibrium between the new LM curve, LM (P2) and the IS curve at output level, Y2. The movement along the IS curve towards a higher level of income arises because of the decline in interest rate that boosts investment and thus aggregate planned expenditure (in the Keynesian cross) and increases the equilibrium level of income or output in the product market. Figure 3.20: Effects of Expansionary Monetary and Fiscal Policy 32 The Effect of Expansionary Policy on AD: In our previous discussion, we have indicated that IS curve is drawn with changes in interest rate and investment; while keeping autonomous consumption, government expenditure, autonomous investment and government expenditure constant. If there is a change in one of these variables, which were assumed fixed, will shift the IS curve. Suppose government increases its spending from G1 to G2 by the amount ( G ); the IS curve will shift to the right from IS1 to IS2. An increase in government spending will increase planned expenditure and thus will cause a change in equilibrium level of income, which is equal to a change in government spending times the multiplier. On the money market, the increase in income will lead to an increase in the transaction demand for money. However, the real money balances (or real money supply) is constant. Given equation, M / P l (Y ) h(r ) , the increase in transaction demand for money, l (Y ) , needs interest rate and thus h(r ) to increase so as to ensure that the money market is in equilibrium. This leads to an upward movement on the LM curve. An overall equilibrium, both product and money market, is ensured at a new income level, at Y Y2 . The IS–LM Model in the Short Run and Long Run The IS–LM model is designed to explain the economy in the short run when the price level is fixed. The short-run equilibrium of the economy is at point K in panel a; where the IS curve crosses the LM curve. The short-run equilibrium income is less than its natural rate as it is shown on the upward slopping long-run aggregate supply curve (LASC). 33 Figure 3.20: Effects of Fiscal and Monetary Policy Changes on AD Curve Point K in Fig. 3.20, panel (b) describes the short-run equilibrium because it assumes that the price level is stuck at P1. At this point, there is insufficient demand for goods and services to tap the potential of the economy or operate at the natural level of output. Eventually, low aggregate demand for goods and services causes prices to fall, and the economy moves towards its natural rate. When the price level reaches P2, the economy moves to point C, which is the long-run equilibrium. The aggregate supply and aggregate demand diagrams in panel b show, the quantity of goods and services demanded equals the natural rate of output at point C. This long-run equilibrium is also observed in the IS–LM diagram. The fall in the price level raises real money balances and therefore shifts the LM curve to the right by a shift in the LM curve. 3.7. Conclusion IS and LM model is a systematic representation of the interactions between demand and supply both in the product and money markets. The model also helps to capture the fiscal and monetary policy effects on the economy. The Keynesian cross helps to derive the IS curve that represent the equilibrium conditions in the product market. The IS curve is drawn by manipulating interest rate and investment, while holding government spending, tax and other fiscal policy instruments constant. The change in the fiscal policy instruments will shift the change in IS. The theory of liquidity preference helps to derive the LM curve, which gives the 34 combination of income and interest rate that maintains the money market at equilibrium. The LM curve is drawn for given level of money supply. A change in real money balances will shift the LM curve. Relaxing the assumption of fixed price levels and changes the price, changes the real money balances and causes a shift to the LM curve. The equilibrium points at the intersection of the IS curve and the LM curves at varied price levels will enable to derive the AD curve. The overall equilibrium level of output of both the product and money market is where the LM and the IS curves intersect. We have the slopes of IS and LM curves: The IS schedule is represented by: Y G [ A br ] = The LM schedule is given by = r ( M / P) k Y h h We can substitute the value of r in the LM equation into the IS equation to get equilibrium level of income in terms of other parameters. (53) Y G [ A b[ M /P k Y], h h Thus, we find the equilibrium value of Y in terms of other parameters as: Y G 1 k G b h A Gb M b 1 k G P h A captures the exogenous fiscal policy measures, autonomous private spending and autonomous household consumption. Once we get equilibrium value of income in numbers, for instance, we could find equilibrium level of interest rate. The change in income as a result of change in A , for instance, G, will be given by: Y G b 1 k G h G The new multiplier captures the effect of crowding-out effect of expansionary government policy on private investment and it is expected to be lower than the previous multipliers and the associated change in Y. 35 The IS-LM model is a very important tool to understand the movement of aggregate macroeconomic variables and change in equilibrium conditions because of fiscal and monetary policy instruments. As the model falls under the social science discipline, it has its own limitations4. Thus, one should not necessarily assume that the predictions of the IS-LM would exactly happen in reality. 4 The discussion of IS-LM model limitations is beyond the scope of the chapter. 36