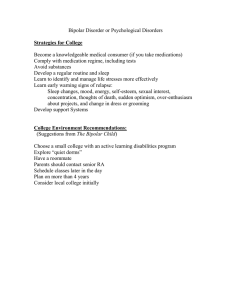

Psychological Medicine (2012), 42, 1429–1439. f Cambridge University Press 2011 doi:10.1017/S0033291711002522 O R I G I N A L AR T I C LE Cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive therapy for bipolar disorders: relapse rates for treatment period and 2-year follow-up T. D. Meyer1,2* and M. Hautzinger1 1 2 Department of Clinical and Developmental Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Germany Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Background. The efficacy of adjunctive psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for bipolar disorder (BD) has been demonstrated in several uncontrolled and controlled studies. However, these studies compared CBT to either a waiting list control group, brief psycho-education or treatment as usual (TAU). Our primary aim was to determine whether CBT is superior to supportive therapy (ST) of equal intensity and frequency in preventing relapse and improving outcome at post-treatment. A secondary aim was to look at predictors of survival time. Method. We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) at the Department of Psychology, University of Tübingen, Germany (n=76 patients with BD). Both CBT and ST consisted of 20 sessions over 9 months. Patients were followed up for a further 24 months. Results. Although changes over time were observed in some variables, they were not differentially associated with CBT or ST. CBT showed a non-significant trend for preventing any affective, specifically depressive episode during the time of therapy. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses revealed that 64.5 % of patients experienced a relapse during the 33 months. The number of prior episodes, the number of therapy sessions and the type of BD predicted survival time. Conclusions. No differences in relapse rates between treatment conditions were observed, suggesting that certain shared characteristics (e.g. information, systematic mood monitoring) might explain the effects of psychosocial treatment for BD. Our results also suggest that a higher number of prior episodes, a lower number of therapy sessions and a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder are associated with a shorter time before relapse. Received 23 March 2011 ; Revised 12 October 2011 ; Accepted 13 October 2011 ; First published online 21 November 2011 Key words : Bipolar disorder, cognitive behaviour therapy, predictors, randomized controlled trial, relapse prevention. Introduction Bipolar disorders (BDs) are more frequent and disabling than originally thought, with many patients showing significant impairment or subsyndromal symptoms between episodes (e.g. Judd et al. 2002 ; Judd & Akiskal, 2003 ; Solomon et al. 2010). Although medication is needed, the role of psychosocial factors in the onset and course of BD has become obvious (e.g. Alloy et al. 2005 ; Johnson, 2005) and has led to the development of several psychosocial interventions. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) relies on the assumption that the interaction of thoughts, behaviours * Address for correspondence : T. D. Meyer, Ph.D., Doctorate in Clinical Psychology, Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, Ridley Building, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK. (Email : thomas.meyer@newcastle.ac.uk) and emotions is the underlying psychopathology, including depression and mania. Indeed, empirical evidence has demonstrated the role of cognitive vulnerability factors such as dysfunctional attitudes or attributional style for BD and mania (e.g. Johnson, 2005 ; Jones et al. 2005 ; Alloy et al. 2009). Several reviews have looked at the efficacy of psychotherapy for BD (e.g. Beynon et al. 2009 ; Miklowitz & Scott, 2009 ; Szentagotai & David, 2010), and in summary indicate that CBT for BD works better than waiting for treatment (Scott et al. 2001), is more beneficial than brief psycho-education (Zaretsky et al. 2008) and has mostly proved to be superior to treatment as usual (TAU) with respect to functioning and relapse prevention (e.g. Lam et al. 2003 ; Ball et al. 2006). Focusing on overall relapse rates from four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in their meta-analysis, Lynch et al. (2010) concluded that CBT is not effective for BD. 1430 T. D. Meyer and M. Hautzinger Although Scott et al. (2006) did not find an overall effect for CBT with regard to relapse prevention for severe BD, they did report that individuals with fewer episodes benefited from receiving CBT. Despite these encouraging results, there are limitations, for example the amount of attention patients in the control groups had received has not been controlled. Waiting for treatment also has its own negative effects, with 30 % of patients dropping out (Scott et al. 2001). By contrast, TAU mostly included regular visits to the psychiatrist and crises management. This was usually provided to all study participants, so that in effect CBT was an add-on intervention. Therefore, the patients treated with CBT received much more attention and support of any kind compared to those in the control conditions. This renders interpretations ambiguous (e.g. Goldfried & Wolfe, 1998). The primary aim of our study was therefore to examine whether the positive results with regard to relapse rates and post-treatment improvements in former studies are still evident if people are randomized to CBT or another treatment condition that is matched in frequency and intensity of contact (i.e. supportive therapy, ST). We used relapse rates as the main outcome variable but also considered symptom levels and indicators of cognitive vulnerability (e.g. locus of control). It was expected that CBT would lead to lower relapse rates, decrease symptoms levels and cognitive vulnerability (e.g. increased internal locus of control). A secondary aim was to test whether illnessrelated variables that have been identified in other studies predict survival time, specifically length of treatment, number of prior episodes, age of onset, medication, psychosocial functioning and type of BD (e.g. Miklowitz et al. 2003 ; Scott et al. 2006, 2007 ; Zaretsky et al. 2008). Method Participants Recruitment took place in the Department of Psychology, University of Tübingen, Germany, between August 1999 and September 2004. The patients were either referred by local hospitals, psychiatrists or were self-referrals due to public information in newspapers or on the radio. Participants were invited to a screening session in which they were informed about the study and gave written informed consent. Baseline assessment consisted of at least three consecutive sessions, in which clinical interviews (e.g. SCID-I and SCID-II) and self-ratings (e.g. the Beck Depression Inventory, BDI) were completed. The inclusion criteria for the study were (a) a primary disorder of BD according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994), (b) age between 18 and 65 years, and (c) willingness to continue current or start medication. Exclusion criteria were : (a) the primary diagnosis is a non-affective disorder including schizo-affective disorder, (b) current major affective episode (depressed, mixed or mania according to SCID-I) or Bech–Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (BRMS ; Bech & Rafaelsen, 1980) score >14 or Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (BRMAS ; Bech et al. 1978) score >9, (c) substance-induced affective disorder, or affective disorder due to a general medical condition, (d ) current substance dependency requiring detoxification (abuse did not qualify for exclusion), (e) serious cognitive deficits (IQ <80), and ( f ) being currently in psychological treatment. Treatment conditions Patients were randomly allocated to individual CBT or ST using a stratified randomization strategy controlling for gender, bipolar I or II disorder, and age of onset (before/after age of 20 years). Treatment started within 2–4 weeks after the assessments. Both treatments consisted of 20 sessions (50–60 min) distributed over 9 months. The first 12 sessions were provided on a weekly basis, then biweekly sessions were offered for the next 2 months and the remaining sessions were scheduled monthly. Manuals were provided for both treatments ; with the CBT one being published (Meyer & Hautzinger, 2004). Both treatment conditions included information (e.g. symptoms, aetiology, medication) and mood monitoring in the form of a mood diary. The difference between therapies was such that, in the ST condition, therapists adopted a client-centred focus, meaning that whatever problems the patient presented were dealt with by providing emotional support and general advise. If no specific topic was mentioned by the patient, information about BD and medication was delivered by the therapist without referring to written or any other material. In contrast to the CBT, no efforts were made to specifically link this information to the individual’s biography or experience. The mood diary was checked by the therapist who provided brief feedback (e.g. regularity of medication, of sleep and overall mood) or probed for missing information but without using any CBTrelated techniques such as guided discovery, problem solving or reality testing. CBT covered (a) an information and motivation module (providing and jointly elaborating on information and an understanding of BD, its symptoms, aetiology, course, triggers and pharmacotherapy based on and linked to the individual’s experience, but also addressing, for example in this context, potentially dysfunctional beliefs about BD and medication), (b) an individual relapse module (including life chart CBT versus ST for BD analysis, identification and monitoring of individual early warning symptoms for mania and depression, functional behaviour analysis or risky behaviours, coping with prodromal symptoms), (c) cognitive and behavioural strategies dealing with depression and mania (e.g. cognitive restructuring, activity schedule/ daily routine, planning pleasurable activities), and (d) training of communication skills and/or problemsolving skills depending on the individuals strengths and deficits. Therapists (n=8, one being T.D.M.) had a least 1-year postgraduate training in CBT and had attended a specific 2-day workshop about CBT and ST for BD with role plays and video training. All therapy sessions were video-taped and weekly supervision was provided. Materials and procedures SCID-I and SCID-II (First et al. 1996, 1997) were used by trained clinical psychologists to diagnose mental health problems at baseline and in the follow-up period. All interviews were videotaped, and a random sample of 53 patients was used to estimate reliability, which proved to be excellent (k=0.93 for bipolar I, k=0.89 for bipolar II). Relapse was defined as any mood episode that fulfilled DSM-IV criteria. Throughout the therapy period recordings were made of hospitalizations and episodes obtained by the clinicians’ notes and from the patients’ mood diaries [including also weekly assessments using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D ; Radloff, 1977 ; Meyer & Hautzinger, 2003)]. Severity of symptoms and functioning was also assessed repeatedly throughout the study period using the BRMS, the BRMAS and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS), with good reliability : intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)=0.87, 0.77 and 0.81 respectively. Several selfrating measures were used, such as the BDI (Beck & Steer, 1987 ; a=0.89) and the Self-Rating Mania Inventory (SRMI ; Shugar et al. 1992 ; a=0.94). In addition, the Locus of Control for health and illness (LC ; Lohaus & Schmitt, 1989) and the Disease Concept Scale [‘ Krankheitskonzeptskala ’ (KK) ; Linden et al. 1988] were used. The 21 items of the LC are rated on a scale from 1 (totally true) to 6 (not at all true) and three composite scores can be calculated : internal LC (a=0.89), external LC – powerful others (a=0.76), and external LC – chance (a=0.88). The KK is so far the only existing German scale that has been evaluated to assess subjective illness concepts of patients. All 29 items are rated on a five-point scale (from 0=do not agree at all to 4=totally agree). Seven subscales were derived through factor analysis : trust in medication, trust in psychiatrist, negative expectations, guilt, 1431 chance, vulnerability, and idiosyncratic assumptions [0.67 (chance) <a <0.85 (trust in medication)]. The LC and KK scales were assumed to be psychological concepts related to adherence and to reflect effects of psychotherapy. To estimate adherence to medication, the Somatotherapy Index (Bauer, 2001) was used. The best available data were used (mostly blood serum levels) to ensure the most accurate reporting of the maximum level of somatotherapy across medication types (i.e. ‘ 0 ’ no or very low levels of medication ; ‘ 4 ’ indicating optimal pharmacotherapy). Cognitive testing was undertaken to ensure that intellectual functioning was sufficient, using the intelligence test (Leistungsprüfsystem, LPS) devised by Horn (1983). After baseline assessment (t0), participants were randomly assigned to CBT or ST. Immediately following treatment, the post-treatment assessment (t1) took place with raters who were blind to the treatment conditions. Further follow-up assessments took place every 3 months for the first year and one further assessment after 2 years. The analysis reported here focuses on the immediate effects of CBT on symptoms and psychological variables comparing pre- (t0) and post-treatment assessment (t1) and also relapse rates for the total 33-month period. Statistical analysis In the original planning stage, a power analysis assuming a large effect size (with power=0.80, p<0.05) suggested a required sample size of 2r20 patients to detect mean differences and 2r26 for detecting differences in x2 tests (Cohen, 1988). According to Chambless & Hollon (1998), such a sample size should reveal differences that are clinically meaning. Baseline comparisons were made if appropriate parametrically, using t tests for dimensional measures and x2 for categorical variables. All main analyses are presented as intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses. Using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., USA), treatment effects were analysed with an ANOVA with repeated measurements including the factors time, treatment condition and their interaction. For the analyses, exact p values were reported up to p=0.15. The primary hypothesis referring to survival time (in weeks) was analysed using Kaplan–Meier curves with significance tests based on the log rank test. The secondary hypothesis was tested by running Cox proportional regressions to estimate the effects of the specified covariates for the whole sample including therapy condition : number of prior episodes, diagnosis (coded as ‘ 1 ’ for bipolar I and ‘ 2 ’ for bipolar II), age of onset, medication adherence (Somatotherapy Index, 0 to 4), number of therapy sessions, and baseline overall functioning (GAS). Skew, kurtosis and univariate outliers were 1432 T. D. Meyer and M. Hautzinger Total sample n = 141 n = 11 just phone contact n = 23 baseline assessment incomplete (e.g. in psychotherapy) n = 107 Baseline assessment completed n = 20 No bipolar disorder diagnosis n = 1 opiate dependency n = 1 alcohol dependency n = 9 ‘informed consent’ withdrawn n = 76 randomized CBT n = 38 ST n = 38 Episodes during treatment: any mood: n = 12 depressed: n = 7 (hypo)manic: n = 10 Episodes during treatment: any mood: n = 20 depressed: n = 14 (hypo)manic: n = 8 n = 33 completers n = 5 dropouts n = 32 completer n = 6 dropouts Fig. 1. Flowchart of recruitment of patients. CBT, Cognitive behaviour therapy ; ST, supportive therapy. checked, and the ‘ number of episodes ’ was transformed using the natural logarithm (ln). No transformation improved the skew of the ‘ number of therapy sessions ’ so the original raw scores were used. Two multivariate outliers were identified (both men in their sixties with a co-morbid personality disorder, one CBT/one ST), but because their inclusion did not change the results, they were included in the analyses. Analyses were conducted separately for any new affective episode, and also for depressive and manic episodes (including hypomanic and mixed episodes). Results Patient characteristics Overall, 141 patients contacted us (Fig. 1). In some cases the only contact was by telephone. Twenty individuals did not have a primary BD. Two patients were excluded because they had a current substance dependency. Nine patients withdrew their informed consent prior to start of treatment (mainly because of the required videotaping of the therapy sessions). Comparing the randomized patients to the nonparticipating patients revealed no differences with respect to gender, type of BD, lifetime diagnosis of alcohol- or substance-related disorders, personality or anxiety disorders (all x2 or Fisher’s exact tests p>0.10). The same was true for age, age of onset, current medication adherence or current level of depression (all t <j1.15j). Patients who participated had low but significantly higher manic ratings (BRMAS) than those who discontinued [t(77.76)=2.73, p<0.008, d=0.41, mean=1.68 (S.D.=3.22) v. 0.50 (S.D.=0.86)]. Despite their higher subsyndromal manic symptoms, their current psychosocial functioning was considered significantly higher than those who did not continue with the study [t(90)=2.10, p<0.05, d=0.58, mean=69.59 (S.D.=12.64) v. 62.31 (S.D.=12.45)]. Fifty-three (69.7 %) out of the 76 patients were taking at least one mood stabilizer (and in 17 cases this was accompanied by antidepressant medication). Seven (9.2 %) were only on antidepressant medication and 16 (21.1 %) did not take any medication at the beginning of the study. Of the 53 receiving mood stabilizers, the majority (51.3 %, n=39) had one, 13 (17.1 %) had a combination of two and one individual (1.3 %) had three mood stabilizers (lithium : n=30 ; valproate : n=16 ; carbamazepine : n=9 ; antipsychotics : n=13). The groups did not differ in whether they had a mood stabilizer or antidepressant medication [all x2f1.27, N.S. (data not shown)]. CBT versus ST for BD 1433 Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients before treatment (t0) and recurrence rates during follow-up Treatment condition Cognitive behaviour therapy (n=38) Supportive therapy (n=38) Gender : female, n ( %) Age (years), mean (S.D.) Age of onset (years), mean (S.D.) Number of episodes, median (range) 18 (47.4) 44.4 (11.0) 26.6 (9.2) 6 (1–60) 20 (52.6) 43.5 (12.7) 29.8 (12.4) 6 (1–40) 16 (42.1) 15 (39.5) 7 (18.4) 16 (41.0) 16 (41.0) 7 (17.9) x2(2, n=76)=0.11, N.S. 30 (78.9) 8 (21.1) 30 (78.9) 8 (21.1) x2(1, n=76)=0.00, N.S. 8 (21.1) 6 (15.8) 8 (21.1) 14 (38.9) 7 (18.4) 13.50 (9.8) 17.7 (11.0) 6.08 (4.70) 2.34 (3.69) 67.4 (12.4) 2.7 (1.5) 56.9 (7.2) 12 (31.6 %) 9 (23.7) 4 (10.5) 10 (26.3) 14 (36.18 8 (21.1) 11.03 (7.60) 19.3 (11.2) 5.55 (5.24) 1.03 (2.56) 71.8 (12.6) 2.6 (1.3) 59.6 (6.2) 20 (52.6 %) x2(1, n=76)=0.08, N.S. x2(1, n=76)=0.46, N.S. x2(1, n=76)=0.29, N.S. x2(1, n=76)=0.03, N.S. x2(1, n=76)=0.08, N.S. t(74)=1.29, N.S. t(73)=0.63, N.S. t(74)=0.46, N.S. t(74)=1.81, N.S. t(74)=1.55, N.S. t(74)=0.15, N.S. t(74)=x1.58, N.S. x2(1, n=76)=3.46, p=0.06 19 (50) 16 (42.1) 10 (26.3) 10 (26.3) 0 (0.0) 26 (68.4) 17 (44.7) 11 (28.9) 5 (13.2) 7 (18.4) 1 (1.3) 23 (60.5) Marital status, n ( %) Single Married Divorced Diagnosis, n ( %) Bipolar I Bipolar II Co-morbid Axis I diagnosis, n ( %) Alcohol abuse/dependency Substance abuse/dependency Anxiety disorders Psychotic mood-related symptoms, n ( %) Personality disorder, n ( %) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Self-Rating Mania Scale (SRMS) Bech–Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (BRMS) Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMAS) Global Assessment Scale (GAS) Somatotherapy Indexa Cognitive functioningb Recurrence (9 months treatment) Recurrence (9 months plus 24 months follow-up), n ( %) Major depressive episode Any manic episodes Hypomanic episode Manic episode Mixed episode Any affective episode Statistics x2(1, n=76)=0.61, N.S. t(74)=0.32, N.S. t(74)=x1.28, N.S. Mann–Whitney U=708.5, Z=x0.14, N.S. S.D., a Standard deviation ; N.S., not significant. The Somatotherapy Index is a score varying between 0 and 5 to describe the quality of prescribed and taken medication based primarily on blood serum levels (M. Bauer et al., unpublished manuscript). b Cognitive functioning was assessed with an intelligence test (Leistungsprüfsystem, Horn, 1983), which provide standardized t scores (mean=50, S.D.=10). Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the final sample. No significant baseline differences between CBT and ST were found for any of the variables, suggesting successful randomization. Completers were those patients who attended at least 16 out of 20 sessions. A total of 11 patients attended less than 16 sessions and were considered drop-outs (14.5 %). Most patients (82 %) dropped out before session 10. Dropping out was not related to treatment condition, sex, marital status, type of BD or co-morbid substance use or anxiety disorders (all x2 f1.81 or Fisher’s exact test p>0.15). The same was true for age, current symptoms of depression, number of episodes or psychosocial functioning according to the GAS (all t<1.58). Drop-outs were more likely to have a personality disorder diagnosis (54.5 %) than completers (13.8 %) (Fisher’s exact test p=0.006). When excluding drop-outs, the average number of sessions attended was 18.53 (S.D.=1.09) for CBT and 19.28 (S.D.=1.17) for ST. 1434 T. D. Meyer and M. Hautzinger Table 2. Symptoms and indicators of psychosocial functioning pre- (t0) and post-intervention (t1) Outcome Drop-outs Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Self-Rating Mania Inventory (SRMS) Bech–Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (BRMS) Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMAS) Global Assessment Scale (GAS) Medication adherence (Somatotherapy Index)a LC : internal LC : external – powerful others LC : external – chance Trust in medication (KK) Trust in psychiatrist (KK) Negative expectations (KK) Feeling of guilt (KK) Chance (KK) Personal vulnerability (KK) Idiosyncratic assumptions (KK) Cognitive behaviour therapy Supportive therapy n ( %) n ( %) Mean S.D. 5 (13.2) t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 t0 t1 37 38 38 38 37 38 38 Mean S.D. Statistics 7.60 4.35 11.22 10.09 5.24 4.53 2.56 1.19 12.62 16.79 1.41 1.47 5.60 5.59 5.72 5.36 7.29 7.02 4.05 4.48 2.90 2.39 3.42 3.31 2.27 2.48 3.72 3.95 2.68 2.85 3.57 3.01 x2(1, n=76)=0.11 T : F=17.81, p<0.001 TrI : F=1.86 T : F=7.07, p<0.01 TrI : F=1.05 T : F=10.26, p<0.005 TrI : F=0.06 T : F=2.14 TrI : F=0.53 T : F=8.90, p<0.01 TrI : F=0.17 T : F=0.00 TrI : F=0.03 T : F=12.68, p<0.011 TrI : F=0.17 T : F=0.13 TrI : F=0.84 T : F=10.29, p<0.01 TrI : F=0.10 T : F=0.00 TrI : F=2.63, p=0.11 T : F=0.89 TrI : F=3.55, p=0.06 T : F=4.559, p<0.05 TrI : F=0.02 T : F=0.02 TrI : F=1.56 T : F=3.23, p=0.08 TrI : F=0.74 T : F=0.35 TrI : F=0.68 T : F=4.82, p<0.05 TrI : F=0.00 6 (15.8) 13.50 10.93 17.65 15.83 6.08 4.29 2.34 1.64 67.37 73.29 2.55 2.53 26.42 28.13 24.24 24.92 20.34 18.03 13.14 13.78 9.95 10.58 7.53 6.79 4.71 5.03 7.27 6.92 6.13 6.45 6.92 6.21 9.38 9.17 10.98 11.66 4.70 5.08 3.69 3.37 12.43 14.11 1.59 1.45 7.54 5.15 5.34 4.88 7.74 7.10 3.77 4.10 2.78 3.22 4.17 3.43 3.04 2.40 3.53 3.70 3.21 3.06 3.66 4.02 38 38 38 38 38 38 37 11.03 6.00 19.27 15.18 5.55 3.47 1.03 0.79 71.82 76.32 2.50 2.53 26.24 28.41 25.59 25.30 22.66 20.76 13.21 12.61 10.05 9.84 8.00 7.36 5.34 4.95 8.63 7.63 6.11 6.05 8.30 7.62 KK, Krankheitskonzeptskala (Disease Concept Scale) ; LC, Locus of Control ; S.D., standard deviation ; T, F value for main effect of time ; I, F value for main effect of treatment condition ; IrT, F value for the interaction term of time and treatment condition. a The Somatotherapy Index is a score varying between 0 and 5 to describe the quality of prescribed and taken medication based primarily on blood serum levels (M. Bauer et al., unpublished manuscript). Primary outcomes : post-treatment effects and relapse rates Post-treatment effects Descriptive data for baseline and post-treatment symptoms and indicators for psychosocial functioning are presented in Table 2. This table shows that symptoms of depression decreased significantly over time, but there was no significant timertreatment interactions for self-ratings or observer ratings. Self-rated but not clinician-rated manic symptoms decreased significantly over time. Psychosocial functioning (GAS) improved, but this was not specific to either treatment condition. Using the Somatotherapy Index to quantify current medication adherence based on blood levels of different medications, there was no evidence for any change. Internal LC increased significantly over time and external LC (chance) decreased but no significant timertreatment interaction was observed. External LC (powerful others) did not change over time. Some of the illness-related cognitions (e.g. negative expectations, idiosyncratic assumptions) changed over time in the expected direction, but no significant effect CBT versus ST for BD 1435 was found favouring CBT. There was only a nonsignificant trend for CBT-treated patients to trust their clinicians more after therapy. decrease in risk for a recurrence compared to bipolar II patients. Examination of the logarithm of the number of episodes for each increase of one point increased the risk for relapse by 7 %. However, risk for relapse decreased by 10 % with each therapy session. Analysis of survival time until first depressive episode indicates that again the covariates contributed significantly to the prediction [log likelihood x2(df= 7)=20.68, p<0.005, R2=0.24], with bipolar I versus II and the number of therapy sessions being significant predictors. More therapy sessions were again associated with longer time until a depressive episode, and bipolar II was associated with increased risk for a depressive relapse. A different picture emerged for manic-like episodes. Although the number of prior episodes emerged as a significant predictor of shortened survival time, overall the set of covariates did not significantly predict survival time [log likelihood x2(df=7)=8.11, N.S., R2=0.10 (Table 3)]. Relapse rates Discussion Overall, 64.5 % (n=49) of the patients had at least one recurrence within the 33 study months (see Table 1). On average, the first recurrence occurred 67.53 (S.E.= 9.21) weeks after treatment had started for the CBT group and 66.25 (S.E.=10.58) weeks for the ST group. Kaplan–Meier analyses revealed that survival times until first recurrence of any affective episode did not differ significantly between therapy conditions [log rank (Mantel–Cox) x2=0.004, N.S. (Fig. 2)]. With regard to first depressive recurrence, the mean survival times were 86.05 (S.E.=9.75) and 88.86 (S.E.=11.15) weeks for CBT and ST respectively (log rank x2=0.02, N.S.). The corresponding survival times for any hypomanic, manic or mixed episode were 95.85 (S.E.=10.05) and 113.60 (S.E.=0.97) weeks, again revealing no significant difference in survival time (log rank x2=1.33, N.S.). Several reviews have concluded that, overall, studies have shown that adjunctive psychotherapy has beneficial effects for patients with BD (e.g. Beynon et al. 2009 ; Miklowitz & Scott, 2009 ; Szentagotai & David, 2010). However, at least when focusing on the studies evaluating CBT, it is only justified to conclude that adjunctive CBT is mostly more effective than TAU, waiting for treatment or a brief psychoeducation. We therefore addressed the question of whether CBT shows any evidence for post-treatment benefits and relapse prevention that go beyond those of an ST equal in number and duration of sessions and including information and a mood diary. Disregarding any trends, the general picture is that the changes observed over time in both CBT and ST in subsyndromal symptoms and cognitive factors such as LC were the same, but that the treatments did not differ on post-treatment outcome. The same was true for rates of recurrence and time to recurrence. Partially in line with prior studies (e.g. Scott et al. 2006 ; Zaretsky et al. 2008), higher risk for any recurrence was predicted by a greater number of prior episodes, a lower number of therapy sessions and bipolar II disorder. The pattern for depressive and manic recurrence was different but it is not clear whether this is due to low power for distinct episodes or evidence for polarity-specific predictors (e.g. Johnson & Meyer, 2004). Our results contrast with other studies that have shown that psychosocial treatments significantly reduced relapse rates (e.g. Lam et al. 2003 ; Miklowitz et al. 2003). However, most studies either used a waiting list control group, TAU or fewer sessions Cumulative proportion without any episode 1.00 CBT (n = 38) ST (n = 38) .80 .60 .40 .20 .00 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 Time untill first recurrence (in weeks) Fig. 2. Cumulative survival functions with regard to recurrence of any affective episode for cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and supportive therapy (ST). Secondary outcomes : predictors of survival time Proportionality of hazards was tested and was given for all but ‘ number of prior episodes (ln) ’ so that its interaction with time was included in the analysis. The results of the Cox regression model are displayed in Table 3. Confirming the prior analysis, there was no statistically significant effect of therapy condition after adjusting for the seven covariates [x2 log likelihood x2(df=1)=0.11, p=0.75, R2=0.001]. Survival time till any mood episode was, however, predicted by the set of covariates [log likelihood x2(df=7)= 20.12, p<0.005, R2=0.23], with three predictors being significant and not including 1.00 in the confidence interval. Patients with bipolar I disorder had a 60 % 1436 T. D. Meyer and M. Hautzinger Table 3. Predictors in the Cox regression models for recurrence of depression, mania and any affective episode Variables Any affective episode Diagnosis Medication adherence Age of onset Psychosocial functioning (GAS t0) Number of episodes Number of episodesrtime Number of therapy sessions Treatment condition Recurrence of depression Diagnosis Medication adherence Age of onset Psychosocial functioning (GAS t0) Number of episodes Number of episodesrtime Number of therapy sessions Treatment condition Recurrence of mania Diagnosis Medication adherence Age of onset Psychosocial functioning (GAS t0) Number of episodes Number of episodesrtime Number of therapy sessions Treatment condition B (S.E.) Wald OR 95 % CI x0.91 (0.37) 0.04 (0.11) 0.20 (0.01) x0.01 (0.01) 0.57 (0.25) x0.16 (0.01) x0.11 (0.04) 0.10 (0.30) 6.07** 0.00 2.13 0.39 5.27** 6.77*** 6.45** 0.11 0.40 1.00 1.02 0.99 1.77 0.98 0.90 1.10 0.20–0.83 0.81–1.25 0.99–1.05 0.97–1.02 1.09–2.87 0.97–1.00 0.83–0.98 0.61–1.96 x1.05 (0.41) x0.07 (0.12) 0.03 (0.02) x0.02 (0.02) 0.47 (0.29) x0.02 (0.01) x0.11 (0.05) x0.01 (0.01) 6.65*** 0.30 3.81* 1.16 2.70 4.70** 4.95** 0.00 0.35 0.94 1.03 0.98 1.60 0.98 0.90 0.99 0.16–0.78 0.73–1.19 1.00–1.06 0.96–1.01 0.91–2.81 0.07–1.00 0.81–0.98 0.97–1.00 x0.60 (0.48) x0.06 (0.15) x0.02 (0.02) 0.00 (0.02) 0.71 (0.32) x0.01 (0.01) x0.07 (0.08) 0.51 (0.40) 1.57 0.19 0.82 0.03 4.95** 2.36 0.96 1.62 0.55 0.94 0.98 1.00 2.04 0.99 0.93 1.66 0.21–1.40 0.71–1.25 0.95–1.02 0.97–1.04 1.09–3.81 0.98–1.00 0.80–1.08 0.98–1.00 GAS, Global Assessment Scale ; S.E., standard error ; OR, odds ratio ; CI, confidence interval. Diagnosis coded ‘ 1 ’ as bipolar I and ‘ 2 ’ as bipolar II. Number of prior episodes were logarithmically transformed (ln). Medication adherence was scored according to the Somatotherapy Index : 0=no medication and 4=optimal level of medication. Treatment condition coded ‘ 0 ’=supportive therapy (ST), ‘ 1 ’=cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. (e.g. Zaretsky et al. 2008). As Colom et al. (2003) used an unstructured group setting as a control condition, their study and ours are not directly comparable ; they focused on group treatment whereas we had an individual therapy setting. Furthermore, our ST included information and daily mood monitoring. Most closely resembling our ST condition is the ‘ intensive clinical management ’ used by Frank et al. (2005) as a control group in their RCT evaluating interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT). Initial analyses revealed that it is not the specific kind of treatment per se but the continuity of the treatment condition from the acute to the maintenance phase that was beneficial (Frank et al. 1999). What do our results imply ? Time effects do not necessarily reflect treatment effects because other factors could also contribute to or account for those changes. Non-significant differences in relapse rates can indicate either a lack of efficacy for both CBT and ST or equal effectiveness. The pattern of results (decreases in depression, increases in psychosocial functioning, no changes in medication adherence, specific changes in LC) does resemble other studies (e.g. Scott et al. 2001 ; Lam et al. 2003). Very few other studies have included such a long follow-up of 2 years in addition to the treatment period, but the overall relapse rate of 64.5 % for 33 months is still within the range of relapse rates reported by some others (e.g. Colom et al. 2003 : 66.7 % v. 91.7 % ; Lam et al. 2005 : 63.8 % v. 84 %). We therefore conclude that the observed effects are unlikely in the absence of any treatment added to medication. The question remains : why did CBT and ST lead to these comparable outcomes ? First, information was incorporated in both conditions and is generally considered essential in all psychosocial treatments for BD (Scott et al. 2007 ; Miklowitz & Scott, 2009). Second, the mood diary was originally used to increase the CBT versus ST for BD credibility of our ‘ control condition ’ and to disguise the outcome of the randomization process. However, we consider that the self-monitoring proved to be central for many patients and triggered in many patients self-management and self-regulation processes regardless of the treatment condition. Before drawing any final conclusions, some limitations should be considered. First, the sample size might be considered small. Although we acknowledge that this study is smaller than others (e.g. Lam et al. 2003, 2005 ; Scott et al. 2006), the sample was larger than needed according to our original power analysis. Additionally, the effect size of R2=0.001 for treatment effects with regard to recurrences implies that only an enormous sample would potentially find any evidence for differential effects or moderators for CBT versus ST. Second, we did not formally assess adherence to the treatment manuals. We cannot totally rule out that this could have affected the results, but the training and especially the weekly video-based supervision were aimed at reducing risk of deviating from the manuals. Third, a potential bias in participation and drop-out was observed, which affects generalizability of the results but this is not surprising (e.g. Shea et al. 1990 ; McFarland & Klein, 2005). However, we were less restrictive in our inclusion criteria than other studies trying to increase external validity. In summary, our study adds to the complex picture that CBT might work better when there is nothing else in place (e.g. waiting, TAU), but we did not find much evidence for specific effects of CBT for BD. Given that there are several psychological approaches for BD, future research should focus on the question of matching patients to treatments. Furthermore, with regard to depression, different treatments have been developed so that treatment options now differ for acute depression, chronic depression and recurrent depression (e.g. McCullough, 2000 ; Segal et al. 2002 ; Barton et al. 2008). A similar approach might be needed for improving outcomes in patients with bipolar I or II disorder or those with different co-morbidities. Acknowledgements This research was supported by a grant provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG ME 1681/6-1 to 6-3). We are indebted to all the therapists and independent raters, especially Drs P. Peukert and K. Salkow, and also the research assistants for all their work, support and help. We also especially thank Professor J. Scott (Newcastle University) who provided very helpful and highly valued comments on an earlier draft of this paper with regard to the analyses, and Dr J. Rogers (Newcastle University) for final editing and proofreading. 1437 Declaration of Interest None. References Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, Neeren AM (2005). The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder : environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clinical Psychology Review 25, 1043–1075. Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Gerstein RK, Keyser JD, Whitehouse WG, Urosevic S, Nusslock R, Hogan ME, Harmon-Jones E (2009). Behavioral Approach System (BAS) – relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders : concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 118, 459–447. APA (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association : Washington, DC. Ball JR, Mitchell PB, Corry JC, Skillecorn A, Malhi GS (2006). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder : focus on long-term change. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67, 277–286. Barton S, Armstrong P, Freeston M, Twaddle V (2008). Early intervention for adults at high risk of recurrent/chronic depression : cognitive model and clinical case series. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 36, 263–282. Bauer MS (2001). The collaborative practice model for bipolar disorder : design and implementation in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. Bipolar Disorders 3, 233–244. Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ (1980). The use of rating scales exemplified by a comparison of the Hamilton and the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 62 (Suppl. 285), 126–131. Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ, Kramp P, Bolwig TG (1978). The mania rating scale : scale construction and inter-observer agreement. Neuropharmacology 17, 430–431. Beck AT, Steer RA (1987). The Beck Depression Inventory. The Psychological Corporation : San Antonio, TX. Beynon S, Soares-Weiser K, Woolscott N, Duffy S, Geddes J (2009). Psychosocial interventions for the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder : systematic review of controlled trials. British Journal of Psychiatry 192, 5–11. Chambless DL, Hollon SD (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66, 7–18. Cohen J (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates : Hillsdale, NJ. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reimares M, Goiholea JM, Benabarre A, Terrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Patramon G, Corominas J (2003). A randomized trial of the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry 60, 402–407. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press Inc., Washington, DC. 1438 T. D. Meyer and M. Hautzinger [German version : Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Fydrich T (1997). Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM IV. Hogrefe : Göttingen]. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press Inc., Washington, DC. [German version : Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Fydrich T (1997). Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM IV. Hogrefe : Göttingen]. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Swart HA, Fagiolini AM, Grochocinski V, Houck P, Scott J, Thompson W, Monk T (2005). Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 996–1004. Frank E, Swartz HA, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Weaver EV, Kupfer DJ (1999). Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder : effects of changing treatment modality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108, 579–587. Goldfried MR, Wolfe BE (1998). Toward a more clinically valid approach to therapy research. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology 66, 143–150. Horn W (1983). Leistungsprüfsystem (LPS). Hogrefe : Göttingen. Johnson SL (2005). Mania and dysregulation in goal pursuit : a review. Clinical Psychology Review 25, 241–262. Johnson SL, Meyer B (2004). Psychosocial predictors of symptoms. In Psychological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder (ed. S. L. Johnson and R. L. Leahy), pp. 83–105. Guilford Press : New York. Jones L, Scott J, Haque S, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Caesar S, Cooper C, Forty L, Hyde S, Lyon L, Greening J, Sham P, Farmer A, McGuffin P, Jones I, Craddock N (2005). Cognitive styles in bipolar disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 187, 431–437. Judd LL, Akiskal HS (2003). The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population : re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. Journal of Affective Disorders 73, 123–131. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB (2002). The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 59, 530–537. Lam D, Hayward P, Watkins ER, Wright K, Sham P (2005). Relapse prevention in patients with bipolar disorder : cognitive therapy outcome after 2 years. American Journal of Psychiatry 162, 324–329. Lam D, Watkins ER, Hayward P, Bright J, Wright K, Kerr N, Parr-Davis G, Sham P (2003). A randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60, 145–152. Linden M, Nather J, Wilms HU (1988). Definition, significance and measurement of disease concepts of patients. The Disease Concept Scale for schizophrenic patients [in German]. Fortschritte der Neurologie – Psychiatrie 56, 35–43. Lohaus A, Schmitt GM (1989). Questionnaire for the Assessment of Locus of Control for Illness and Health [in German]. Hogrefe : Göttingen. Lynch D, Laws KR, McKenna PJ (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for major psychiatric disorder : does it really work ? A meta-analytical review of well-controlled trials. Psychological Medicine 40, 9–24. McCullough Jr. JP (2000). Treatment for Chronic Depression. Guilford Press : New York. McFarland BR, Klein DN (2005). Mental health service use by patients with dysthymic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 46, 246–253. Meyer TD, Hautzinger M (2003). The structure of affective symptoms in a sample of young adults. Comprehensive Psychiatry 44, 110–116. Meyer TD, Hautzinger M (2004). Manic Depressive Disorders – Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Relapse Prevention [in German]. Beltz : Weinheim. Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL (2003). A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60, 909–912. Miklowitz DJ, Scott J (2009). Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder : cost-effectiveness, mediating mechanisms, and future directions. Bipolar Disorders 11 (Suppl. 2), 110–122. Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D : a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 3, 385–401. Scott J, Colom F, Vieta E (2007). A meta-analysis of relapse rates with adjunctive psychological therapies compared to usual psychiatric treatment for bipolar disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 10, 123–129. Scott J, Garland A, Moorhead S (2001). A pilot study of cognitive therapy in bipolar disorders. Psychological Medicine 31, 450–467. Scott J, Paykel E, Morriss R, Bentall R, Kinderman P, Johnson T, Abbott R, Hayhurst H (2006). Cognitive behavioural therapy for severe and recurrent bipolar disorders : a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 188, 313–320. Segal ZV, Williams MJG, Teasdale JD (2002). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. Guilford Press : New York. Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin I, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP (1990). Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. American Journal of Psychiatry 147, 711–718. Shugar G, Scherzer S, Toner BB, di Gasbarro J (1992). Development, use, and factor analysis of a self-report inventory for mania. Comprehensive Psychiatry 33, 325–331. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Chunsham MA, Fiedorowicz JG, Boyken L, Keller MB (2010). Longitudinal course of bipolar I disorder : duration of mood episodes. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 339–347. CBT versus ST for BD Szentagotai A, David D (2010). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder : a quantitative meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 71, 66–72. 1439 Zaretsky AE, Lancee W, Miller C, Harris A, Parikh SV (2008). Is cognitive-behavioural therapy more effective than psychoeducation in bipolar disorder ? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 53, 441–448.