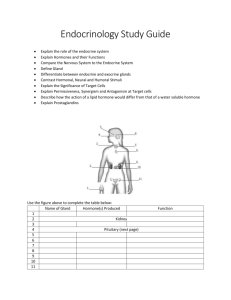

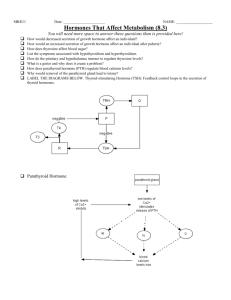

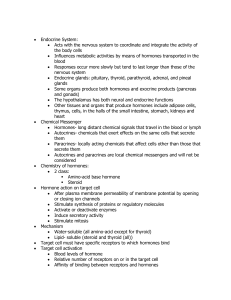

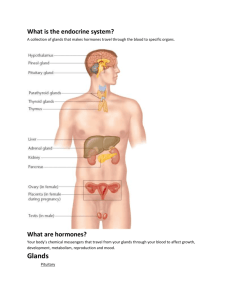

Saladin 6e Extended Outline Chapter 17 The Endocrine System I. Overview of the Endocrine System (pp. 634–637) A. The body has four principal avenues of communication from cell to cell. (p. 634) 1. Gap junctions join single-unit smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, epithelial, and other cells, allowing passage of nutrients, electrolytes, and signaling molecules via the cytoplasm. (Fig. 5.28) 2. Neurotransmitters are released by neurons, diffuse across the synaptic cleft, and bind to receptors. 3. Paracrines are secreted by one cell and diffuse to nearby cells of the same tissue and stimulate them; they are sometimes called local hormones. 4. Hormones in the strict sense are chemical messengers transported by the bloodstream that stimulate physiological responses of cells of another tissue or organ. B. This chapter deals with hormones and some paracrine secretions. The glands, tissues, and cells that secrete hormones are the endocrine system. (p. 634) 1. The study of this system is endocrinology. 2. The most familiar hormone sources are the endocrine glands, such as the pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal glands, etc. (Fig. 17.1) 3. Hormones are also secreted by organs and tissues not usually thought of as glands, such as the brain, heart, small intestine, bones, and adipose tissue. C. The classical distinction between endocrine and exocrine glands has been the absence or presence of ducts. (pp. 634–636) 1. Most exocrine glands secrete their products by way of a duct onto an epithelial surface. (Fig. 5.32) 2. Endocrine glands, in contrast, are ductless and release their secretions into the bloodstream. Hormones were originally called the body’s internal secretions, from which the glands get their name. 3. Exocrine secretions have extracellular effects, whereas endocrine secretions have intracellular effects, altering cell metabolism. 4. Endocrine glands have a high density of blood capillaries, which are of a highly permeable type called fenestrated capillaries that have patches of large pores in their walls. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 2 5. Some glands and secretory cells are not easily classified as one or the other type. For example, liver cells behave as exocrine cells when they secrete bile, but they also secrete hormones into the blood, along with other factors. D. The nervous and endocrine systems complement each other rather than duplicate each other’s functions. (pp. 636–637) (Table 17.1) 1. They differ in means of communication, which is both electrical and chemical in the nervous system and solely chemical in the endocrine system. (Fig. 17.2) 2. The systems also differ in terms of response to stimuli or their cessation. a. The nervous system responds to a stimulus in a few milliseconds, whereas hormone release may occur from several seconds up to days after the stimulus. b. When a stimulus ends, the nervous system stops responding almost immediately, whereas endocrine effects may persist for several days or weeks. c. Under long-term stimulation, most neurons adapt and response declines, but endocrine system response is more persistent. 3. An efferent nerve fiber innervates only one organ and a limited number of cells, so its effects are targeted, while in contrast, hormones circulate throughout the body and have more widespread effects. 4. In terms of similarities, several chemicals function both as neurotransmitters and as hormones, including norepinephrine, dopamine, thyrotroponin-releasing hormone, and others. a. Some hormones, such as oxytocin and ephinephrine, are secreted by neuroendocrine cells—neurons that release secretions into the bloodstream. b. Some hormones and neurotransmitters produce overlapping effects on the same targets, such as glucagon and norepinephrine acting on the liver cells. c. The two systems regulate each other—neurons can trigger hormone secretion, and hormones can stimulate or inhibit neurons. 5. Both neurotransmitters and hormones depend on receptors on the receiving cells. The specificity of target organs or cells allows selective action of circulating hormones. E. In terms of nomenclature, many hormones are denoted by standard abbreviations. (p. 637) (Table 17.2) II. The Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland (pp. 638–645) A. The pituitary gland and hypothalamus have a more wide-ranging influence than any other part of the endocrine system. (p. 638) B. Anatomically, the pituitary is suspended from the floor of the hypothalamus. (pp. 638–640) 1. The hypothalamus is shaped like a flattened funnel and forms the floor and walls of the third ventricle of the brain. (Figs. 14.2, 14.12b) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 3 2. The pituitary gland (hypophysis) is connected to the hypothalamus by a stalk (infundibulum) and housed in a depression of the sphenoid bone, the sella turcica. a. The gland is roughly the size and shape of a kidney bean, usually about 1.3 cm wide; it grows 50% larger in pregnancy. b. It is composed of two structures, the adenohypophysis and the neurohypophysis, which have independent origins and separate functions. (Fig. 17.3) i. The adenohypophysis arises from a hypophyseal pouch that grows upward from the embryonic pharynx. ii. The neurohypophysis arises as a downgrowth of the brain, the neurohypophyseal bud. c. The adenohypophysis constitutes the anterior three-quarters of the pituitary and has two parts. (Figs. 17.4a, 17.5a) i. The anterior lobe (pars distalis) is most distal to the stalk. ii. The pars tuberalis is a small mass of cells that wraps around the stalk. iii. In the fetus, the pars intermedia is also present between the anterior lobe and neurohypophysis but degenerates during later development. d. The hypophyseal portal system connects the hypothalamus to the anterior lobe of the adenohypophysis. (Fig. 17.4b) i. It consists of a network of primary capillaries in the hypothalamus, a group of veins called portal venules that travel down the stalk, and a complex of secondary capillaries in the anterior pituitary. ii. The hypothalamus controls the anterior pituitary by secreting hormones into the primary capillaries. e. The neurohypophysis constitutes the posterior one-quarter of the pituitary and has three parts. i. The median eminence is an extension of the floor of the brain. ii. The infundibulum is the stalk mentioned earlier. iii. The largest part is the posterior lobe (pars nervosa). f. The neurohypophysis is nervous tissue and not a true gland. (Fig. 17.5b) i. The nerve fibers arise from certain cell bodies in the hypothalamus and pass down the stalk as the hypothalamo-hypophyseal tract to end in the posterior lobe. (Fig. 17.4a) ii. The hypothalamic neurons synthesize hormones and transport them to the axons in the posterior pituitary, where they are stored until a nerve signal from the same axons triggers release into the blood. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 4 C. Eight hormones are produced in the hypothalamus: six regulate the anterior pituitary and two are stored in the posterior pituitary and released on demand. (pp. 640–641) (Fig. 17.4) 1. The first six are described as releasing hormones if they stimulate pituitary cells to secrete hormones of their own, or inhibiting hormones if they suppress pituitary secretion. (Table 17.3) a. The releasing or inhibiting effect is identified in the names of the hormones. For example, somastatin inhibits growth hormone, which is known as somatotropin. 2. The other two hypothalamic hormones are oxytocin (OT) and antidiuretic hormone (ADH). a. OT comes mainly from neurons in the right and left paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, named because they lie in the walls of the third ventricle. b. ADH comes mainly from the supraoptic nuclei, named for the location just above the optic chiasm. c. They are stored and released by the posterior pituitary and so are considered posterior lobe hormones even though not synthesized there. D. The six anterior pituitary hormones are summarized as follows. (pp. 641–642) (Table 17.4) 1. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is secreted by pituitary cells called gonadotropes. a. In the ovaries, FSH stimulates secretion of ovarian sex hormones and the development of follicles. b. In the testes it stimulates sperm production. 2. Luteinizing hormone (LH) is also secreted by the gonadotropes; FSH and LH are collectively termed gonadotropins. a. LH stimulates ovulation in females; after ovulation the follicle becomes a yellowish body termed the corpus luteum, from which LH gets its name. b. LH also stimulates the corpus luteum to secrete progesterone. c. In males, LH stimulates the testes to secrete testosterone. 3. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), or thyrotropin, is secreted by cells called thyrotropes; it stimulates growth of the thyroid gland and secretion of thyroid hormone. 4. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), or corticotropin, is secreted by cells called corticotropes. a. Its target organ is the adrenal cortex. b. It stimulates the cortex to release glucocorticoids (especially cortisol), which are involved in the stress response. 5. Prolactin (PRL) is secreted by cells called lactotropes (mammotropes). a. PRL secretion increases during pregnancy but has no effect until after a woman gives birth, when it stimulates the mammary glands to synthesize milk. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 5 b. In males, PRL makes the testes more sensitive to LH and thus enhances the secretion of testosterone. 6. Growth hormone (GH), or somatotropin, is secreted by somatotropes, the most numerous cells of the anterior pituitary. a. The pituitary produces at least a thousand times as much GH as any other hormone. b. GH stimulates mitosis and cellular differentiation to promote tissue growth. 7. The anterior pituitary is thus involved in a chain of events linked by hormones. This chain begins in the hypothalamus and ends with binding of hormones from the anterior pituitary to target organs. (Fig. 17.6) E. The pars intermedia is absent from the adult human pituitary but is present in other animals and in the human fetus. (p. 642) 1. In other species it secretes melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), which influences pigmentation of the skin, hair, or feathers. It has no such function in humans, who do not have circulating MSH. 2. Some anterior lobe cells derived from the fetal pars intermedia produce the polypeptide proopiomelanocortin (POMC), which is not secreted but processed into smaller fragments such as ACTH and endorphins. F. The two posterior lobe hormones are ADH and OT, which are synthesized in the hypothalamus and then transported to the posterior pituitary for storage. (pp. 642–643) 1. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases water retention by the kidneys, reduces urine volume, and helps prevent dehydration. a. ADH also functions as a neurotransmitter and is usually called vasopressin or arginine vasopressin (AVP) in neuroscience. b. It is also called vasopressin because it can cause vasoconstriction, but the concentration required is unnaturally high, so it is of doubtful significance except in pathological states. 2. Oxytocin (OT) has a variety of reproductive functions ranging from intercourse to birth to breast-feeding. a. OT surges during sexual arousal and orgasm. b. In childbirth, it stimulates labor contractions. c. In lactating mothers, it stimulates the flow of milk from mammary gland acini to the nipple. d. It may also play a role in bonding between sexual partners and between mother and infant. G. The control of pituitary hormone secretion in terms of type, timing, and amount are regulated by the hypothalamus, other brain centers, and feedback from target organs. (pp. 643–644) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 6 1. Hypothalamic control enables the brain to monitor conditions within and outside the body and to stimulate or inhibit the pituitary anterior-lobe hormones appropriately. a. In times of stress, the hypothalamus triggers ACTH secretion that leads to secretion of cortisol and mobilization of materials for tissue repair. b. During pregnancy, the hypothalamus induces prolactin secretion so a woman will be prepared to lactate after giving birth. 2. The posterior pituitary is controlled by neuroendocrine reflexes—the release of hormones in response to nervous system signals. a. Dehydration raises the osmolarity of the blood, which detected by hypothalamic neurons called osmoreceptors that trigger ADH release, conserving water. b. Excessive blood pressure stimulates stretch receptors in the heart and certain arteries, and via another neuroendocrine reflex, ADH release is inhibited, increasing urine output. c. The suckling of an infant stimulates nerve endings in the nipple, sending sensory signals to spinal cord, brainstem, and hypothalamus, and finally to the posterior pituitary, causing release of OT and milk ejection. d. Neuroendocrine reflexes can also involve higher brain centers, as when hearing a baby’s cry stimulates a lactating woman to eject milk. 3. Feedback from target organs also regulates the pituitary and hypothalamus through feedback loops. a. Most often, this regulation occurs by negative feedback inhibition, in which the hormone itself inhibits further secretion by binding to the pituitary or hypothalamus. (Fig. 17.7) b. In the pituitary–thyroid system, the feedback inhibition is as follows: i. The hypothalamus secretes TRH. ii. TRH stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete TSH. iii. TSH stimulates the thyroid to secrete TH. iv. TH stimulates the metabolism of most cells throughout the body. v. TH also inhibits the release of TSH by the pituitary. vi. To a lesser extent, TH inhibits the release of TRH by the hypothalamus. c. Steps five and six are the negative feedback inhibition steps, and they ensure that hormone secretion is kept within a certain limit (set point). d. Feedback is not always inhibitory. OT triggers a positive feedback cycle during labor that continues until the infant is born. (Fig. 1.12) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 7 H. Growth hormone is unlike other pituitary hormones in that it is not targeted to just one or a few organs but has widespread effects on the body. (pp. 644–645) 1. GH directly stimulates tissues, especially cartilage, bone, muscle, and fat. It also induces the liver and other tissues to produce insulin-like growth factors (IGF-I and IGFII), also known as somatomedins, which then stimulate target cells. (Fig. 17.6) a. One effect of IGF is to prolong the action of GH. The half-life of GH is only 6 to 20 minutes, whereas that of IGFs is about 20 hours. 2. The mechanisms of GH–IGF action include the following four: a. Protein synthesis. i. Within minutes of its secretion, GH boosts the translation of existing mRNA, and within a few hours it also boosts DNA transcription. ii. It also enhances amino acid transport into cells. iii. GH also suppresses protein catabolism. b. Lipid metabolism. i. GH stimulates adipocytes to catabolize fat and release fatty acids and glycerol. ii. By providing these fuels, GH makes it unnecessary for cells to consume their proteins, which is called the protein-sparing effect. c. Carbohydrate metabolism. i. GH also has a glucose-sparing effect. Its role in mobilizing fatty acids reduces the dependence of cells on glucose so they will not compete with the brain. ii. GH also makes more glucose available for glycogen synthesis and storage. d. Electrolyte balance. i. GH promotes Na+, K+, and Cl– retention by the kidneys. ii. GH enhances Ca2+ absorption by the small intestine. 3. The most conspicuous effect of GH are on bone, cartilage, and muscle growth, especially during childhood and adolescence. a. IGF-I accelerates bone growth at the epiphyseal plates and stimulates multiplication of chondrocytes and osteogenic cells. b. It increases protein deposition in the cartilage and bone matrix. c. In adulthood it stimulates osteoblast activity and the appositional growth of bone, influencing bone thickening and remodeling. 4. GH secretion fluctuates over the course of a day. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 8 a. The GH level in blood plasma rises to 20 nanograms per milliliter or higher during the first 2 hours of deep sleep, and may reach 30 ng/mL in response to vigorous exercise. b. Smaller peaks occur after high-protein meals, but a high-carbohydrate meal tends to suppress GH secretion. c. Trauma, hypoglycemia, and other conditions also stimulate GH secretion. 5. GH levels decline gradually with age. a. Average concentration is 6 ng/mL in adolescence, and one-quarter of that in very old age. b. At age 30, the average adult body is 10% bone, 30% muscle, and 20% fat. At age 75, the average is 8% bone, 15% muscle, and 40% fat. III. Other Endocrine Glands (pp. 645–653) A. The pineal gland is attached to the roof of the third ventricle beneath the posterior end of the corpus callosum. (p. 645) (Figs. 17.1, 17.4a) 1. Its name alludes to a shape resembling a pine cone. 2. A child’s pineal gland is about 8 mm long and 5 mm wide, but after age 7 it regresses, a process called involution. 3. Pineal secretion peaks between the ages of 1 and 5 years and declines 75% by the end of puberty. 4. The pineal gland’s function is somewhat mysterious; it may plan a role in establishing circadian rhythms of physiological function. a. During the night it synthesizes melatonin, a monoamine, from serotonin. i. Melatonin has been implicated in some human mood disorders, although the evidence is inconclusive. ii. Its secretion fluctuates seasonally with changes in day length, and in animals that have seasonal breeding cycles. iii. Melatonin may suppress gonadotropin secretion, since removal of the pineal gland from animals causes premature sexual maturation. b. The pineal gland may regulate the timing of puberty in humans, but this has not been conclusively demonstrated. c. Pineal tumors cause premature puberty in boys, but they also damage the hypothalamus, so it is inconclusive of what causes the effect. B. The thymus is a bilobed gland in the mediastinum superior to the heart, behind the sternal manubrium. It plays a role in the endocrine, lymphatic, and immune systems. (p. 645) 1. In the fetus and infant it is relatively large, sometimes protruding between the lungs nearly as far of the diaphragm and extending upward in to the neck. (Fig. 17.8a) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 9 2. It continues to grow until 5 or 6 years od age. In adults it weighs about 20 g up to age 60 but becomes less glandular with age, remaining as a small fibrous and fatty remnant in the elderly. (Fig. 17.8b) 3. The thymus is a site of maturation for T cells that are critically important for immune defense. 4. It secretes thymopoietin, thymosin, and thymulin, which stimulate development of other lymphatic organs and development and activity of T cells. Insight 17.1 Melatonin, SAD, and PMS C. The thyroid gland weighs about 25 g and is the largest endocrine gland in adults. It is composed of two lobes that lie adjacent to the trachea immediately below the larynx (pp. 646– 647) 1. It is named for the shieldlike thyroid cartilage of the larynx. 2. Near the inferior end, the two lobes are usually joined by a narrow anterior bridge of tissue, the isthmus. (Figs. 17.8, 17.9a) 3. It receives one of the highest rates of blood flow per gram of tissue and is dark reddish brown in color. (Fig. 17.9a) 4. Histologically, it is composed mostly of sacs called thyroid follicles. (Fig. 17.9b) a. Thyroid follicles are filled with a protein rich colloid and lined with a simple cuboidal epithelium of follicular cells. b. These cells secrete thyroxine (T 4, tetraiodothyronine) and triiodothryonine (T3); they are collectively termed thyroid hormone (TH). i. An average adult thyroid secretes 80 μg of TH daily, of which 98% is T4. ii. Most T4 is converted to T3 in target cells. T3 is the more physiologically active form. c. Thyroid hormone is secreted in response to TSH from the pituitary, and the primary effect of TH is to increase the body’s metabolic rate. d. TH raises oxygen consumption and has a calorigenic effect—it increases heat production. i. TH secretion rises in cold weather to help compensate for increased heat loss. It raises respiratory rate, heart rate, and strength of heartbeat, as well as stimulating the appetite. ii. It also promotes alertness, reflex response, secretion of GH, growth of bones, skin, hair, nails, and teeth, and development of the fetal nervous system. 5. The thyroid gland also contains nests of C (clear) cells, or parafollicular cells, between the follicles. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 10 a. These cells secrete calcitonin in response to rising levels of blood calcium, which stimulates osteoblast activity and calcium deposition while antagonizing the action of parathyroid hormone. b. It is important mainly in children, having relatively little effect in adults. D. The parathyroid glands are ovoid glands about 3 to 8 mm long and 2 to 5 mm wide. Four of them are found partially embedded in the posterior surface of the thyroid, separated by a thin fibrous capsule. (p. 647) (Fig. 17.10) 1. Sometimes they occur in other locations ranging from as high as the hyoid bone to as low as the aortic arch; about 5% of people have more than four. 2. They secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH) in response to low blood calcium. E. The adrenal (suprarenal) glands sit like caps on the superior surface of each kidney. (pp. 647–650) (Fig. 17.11) 1. Like the kidneys, they are retroperitoneal. 2. The adult adrenal gland measures about 5 cm vertically, 3 cm wide, and 1 cm anterior to posterior. It weighs about 8 to 10 g in the newborn, but by the age of 2 years following involution of its outer layer, it becomes 4 to 5 g and remains this weight in adults. 3. The gland forms by the merger of two fetal glands with different origins and functions: the gray to dark red adrenal medulla, 10% to 20% of the gland, and the yellowish adrenal cortex, 80% to 90% of the gland. 4. The adrenal medulla has a dual nature, acting as both an endocrine gland and as a ganglion of the sympathetic nervous system. a. Sympathetic preganglionic nerve fibers extend through the cortex to reach chromaffin cells in the medulla. i. These cells have no dendrites or axon, and they release their products into the bloodstream; they are considered neuroendocrine cells. b. Upon stimulation by nerve fibers—usually under conditions of fear, pain or stress—the chromaffin cells release catecholamines. i. About three- quarters is epinephrine, one-quarter is norepinephrine, and a trace is dopamine. ii. These increase alertness and prepare the body for physical activity. iii. They mobilize high energy fuels and boost glucose levels by glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. c. Epinephrine has a glucose-sparing effect in that it inhibits secretion of insulin, so that muscles and other insulin-dependent organs absorb and consume less glucose. d. The adrenal catecholamines also raise heart rate and blood pressure, stimulate circulation and pulmonary airflow, and raise metabolic rate. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 11 e. The catecholamines inhibit functions such as digestion and urine production. 5. The adrenal cortex, which surrounds the medulla, produces more than 25 steroid hormones known as the corticosteroids or corticoids. a. Only five of these are produced in physiologically significant amounts or active forms. b. These five fall into three categories, which are produced in three layers of glandular tissue: mineralocorticoids by the zona glomerulosa; glucocorticoids by the zona fasciculata; and sex steroids by the zona reticularis. c. The zona glomerulosa is a thin layer located just beneath the capsule at the gland surface. i. Glomerulosa refers to the rounded clusters of cells in this zone. ii. The zona glomerulosa mainly secretes aldosterone, a mineralocorticoid that stimulates kidneys to retain sodium and excrete potassium. iii. Because water is retained along with sodium, aldosterone helps to maintain blood volume and pressure. d. The zona fasciculata is a thick middle layer constituting about three-quarters of the adrenal cortex. i. The cells in this zone are arranged in parallel cords (fascicles) separated by blood capillaries, perpendicular to the gland surface. ii. The cells are called spongiocytes because of the abundance of cytoplasmic lipid droplets. iii. The zona fasciculata secretes glucocorticoids in response to ACTH from the pituitary, of which the most potent is cortisol (hydrocortisone), although some effect is due to corticosterone. iv. Glucocorticoids stimulate fat and protein catabolism, gluconeogenesis, and the release of fatty acids and glucose into the blood. v. These hormones also have an anti-inflammatory effect and are used to relieve swelling and other inflammation. vi. Long-term secretion suppresses the immune system. e. The zona reticularis is the narrow, innermost layer, adjacent to the renal medulla. i. Cells of this zone form a branching network (reticulum). ii. They secrete sex steroids, including androgens and smaller amounts of estrogen. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 12 iii. The adrenal androgens are dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, many tissues convert these to testosterone. iv. DHEA is produced in tremendous quantities by the large adrenal glands of the male fetus and plays an important role in prenatal development of the reproductive tract. v. In both sexes, androgens are responsible for development of secondary sexual characteristics in puberty. vi. In men, testosterone produced by the testes greatly overshadows that converted from DHEA, but in women, DHEA provides about 50% of the androgen requirement. vii. The main adrenal estrogen is estradiol; this is of minor importance to women during reproductive years, but is it is the main source of estrogen after menopause. 6. The medulla and cortex are not as functionally independent as once thought; each of them stimulates the other. a. Without stimulation by cortisol, the adrenal medulla atrophies significantly. b. Conversely, some chromaffin cells extend into the cortex, and when stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, these cells stimulate the cortex to secrete corticosterone. F. The pancreas is an elongated, spongy, primarily exocrine gland below and behind the stomach that secretes digestive enzymes—but scattered throughout its exocrine tissue are 1 to 2 million endocrine cell clusters called pancreatic islets (islets of Langerhans). (pp. 650–651) (Fig. 17.12) 1. Although they are less than 2% of pancreatic tissue, the islets secrete hormones of vital importance to glycemia, the blood glucose concentration. 2. An islet measures about 75 by 175 um and contains from a few to 3,000 cells, of which about 20% are alpha cells, 70% are beta cells, 5% are delta cells, and a small number are PP and G cells. a. Alpha (α) cells, or A cells, secrete glucagons between meals when the blood glucose concentration is falling. i. In the liver, glucagons stimulates gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and the release of glucose into the circulation. ii. In adipose tissue, it stimulates fat catabolism and the release of free fatty acids. iii. Glucagon is also secreted in response to rising amino acid levels after a high-protein meal. It promotes amino acid absorption, providing cells with raw material for gluconeogenesis. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 13 b. Beta (β) cells, or B cells, secrete insulin during or immediately following a meal, when glucose and amino acid levels are rising. i. Insulin stimulates cells to absorb these nutrients and store or metabolize them. ii. It promotes the synthesis of glycogen, fat, and protein, and thus the storage of excess nutrients. iii. It also antagonizes the effects of glucagons. iv. Brain, liver, kidneys, and red blood cells absorb and use glucose without insulin, but insulin does promote glycogen synthesis in the liver. v. Insulin insufficiency or inaction is the cause of diabetes mellitus. c. Delta (δ) cell, or D cells, secrete somatostatin (growth hormone–inhibiting hormone) concurrently with the release of insulin by the beta cells. i. Somatostatin inhibits some digestive enzyme secretion and nutrient absorption. ii It acts locally in the pancreas as a paracrine secretion that modulates other islet cells. iii. It partially suppresses the secretion of glucagons and insulin by A and B cells. d. PP cells, or F cells, secrete pancreatic polypeptide that inhibits gallbladder contraction and secretion of pancreatic digestive enzymes. e. G cells secrete gastrin, which stimulates the stomach’s acid secretion, motility, and emptying. The stomach and small intestine also secrete gastrin. 3. Any hormone that raises blood glucose level is called a hyperglycemic hormone.Insulin is a hypoglycemic hormone because it lowers blood glucose level. G. The gonads, ovaries and testes, are like the pancreas in that they are both endocrine and exocrine. (pp. 651–652) 1. Their exocrine products are whole cells—eggs and sperm—and thus they are sometimes called cytogenic glands. 2. Their endocrine products are the gonadal hormones, most of which are steroids. 3. The ovaries secrete chiefly estradiol, progesterone, and inhibin. 4. Each egg develops in its own follicle, which is lined by a wall of granulosa cells and surrounded by a capsule, the theca. (Fig. 17.13a) a. Theca cells synthesize androstenedione, and both theca and granulosa cells convert this to estradiol and lesser amounts of estriol and estrone. b. In the middle of the ovarian cycle, a mature follicle ruptures and releases the egg. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 14 c. The remains of the follicle become the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone for the next 12 days in a typical cycle, or several weeks in the event of pregnancy. i. Inhibin, which is also secreted by the follicle and corpus luteum, suppresses the secretion of FSH by the anterior pituitary. d. The female gonadal hormones contribute to the development of the reproductive system and female physique as well as promoting growth, and they regulate the menstrual cycle, sustain pregnancy, and prepare the mammary glands for lactation. e. A testis consists mainly of seminiferous tubules that produce sperm. f. Its endocrine secretions are testosterone, lesser amounts of other androgens and estrogens, and inhibin. i. Inhibin comes from sustentacular (Sertoli) cells that form the walls of the seminiferous tubules. ii. By limiting FSH secretion, inhibin regulates the rate of sperm production. g. Nestled between the tubules are clusters of interstitial cells (cells of Leydig), the source of the gonadal steroids. (Fig. 17.13b) h. Testosterone stimulates development of the male reproductive system in the fetus and adolescent, development of the male physique in adolescence, and the sex drive. H. Several other tissues and organs secrete hormones or hormone precursors. (pp. 652–653) 1. The skin. Keratinocytes of the epidermis convert a cholesterol-like steroid into cholecalciferol using UV radiation from the sun. a. The liver and kidneys convert cholecalciferol to a calcium-regulating hormone, calcitriol. 2. The liver. The liver is involved in production of at least five hormones. a. It converts cholecalciferol into calcidiol, the next step in calcitriol synthesis. b. It secretes angiotensinogen, a protein that is converted by kidneys, lungs, and other organs into the hormone angiotensin II, which is a regulator of blood pressure. c. The liver secretes about 15% of the body’s erythropoietin (EPO), which stimulates the production of red blood cells by the red bone marrow. d. It secretes hepcidin, a recently discovered hormone involved in iron homeostasis. i. Hepcidin promotes intestinal absorption of dietary iron and mobilization of iron for hemoglobin synthesis and other uses. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 15 e. The liver secretes insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), a hormone that mediates the action of growth hormone. 3. The kidneys. The kidneys produce three hormones. a. They convert calcidiol into calcitriol (vitamin D), which raises blood concentration of calcium by promoting its intestinal absorption. b. They secrete renin, an enzyme that converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I. i. As angiotensin I circulates, it is converted to angiotensin II by angiotensin-coverting enzyme (ACE) in the linings of certain blood capillaries. Angiotensin II constricts blood vessels and raises blood pressure. c. The kidneys secrete about 85% of the body’s erythropoietin. 3. The heart. Rising blood pressure stretches the heart wall and stimulates atrial muscle to secrete atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and ventricle muscle to secrete brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). a. BNP was so named because it was first discovered in the brain. The heart produces five times as much ANP as BNP. b. Both peptides increase sodium excretion and urine output and oppose the action of angiotensin II. 5. The stomach and small intestine. These contain enteroendocrine cells that secrete at least ten eneteric hormones that coordinate actions of the digestive system. a. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is secreted when fats arrive and stimulates the gall bladder to release bile. It also acts as an appetite suppressant in the brain. b. Gastrin is secreted by cells in the stomach upon arrival of food and stimulates hydrochloric acid secretion. c. Ghrelin is one of the enteric hormones that act on the hypothalamus; it is secreted when the stomach is empty, producing the sensation of hunger. d. Peptide YY (PYY), secreted by cells of the small and large intestines, signals satiety. 6. Adipose tissue. Fat cells secrete the hormone leptin, which has long-term effects on appetite-regulating centers of the hypothalamus. a. A low level of leptin (low body fat) increases appetite, whereas a high level of leptin (high body fat) tends to decrease appetite. b. Leptin also serves as a signal for the onset of puberty, which is delayed in persons with abnormally low body fat. 7. Osseous tissue. Osteoblasts secrete the hormone osteocalcin, which increases the number of pancreatic beta cells, pancreatic output of insulin, and the insulin sensitivity of other body tissues. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 16 a. Osteocalcin seems to inhibit fat deposition and the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. 8. The placenta. This organ functions during pregnancy for fetal nutrition and waste removal, but also secretes estrogen, progesterone, and other hormones that regulate pregnancy and stimulate development of the fetus and mammary glands. 9. Endocrine organs and tissues other than the hypothalamus and pituitary are reviewed in Table 17.5. IV. Hormones and Their Actions (pp. 655–665) A. Hormones fall into three chemical classes: steroids, peptides, and monoamines. (p. 655) (Fig. 17.14) (Table 17.6) 1. Steroid hormones are derived from cholesterol. a. They include the sex hormones and corticosteroids produced by the adrenal gland. b. Calcitriol, the calcium-regulating hormone, is not a steroid but is derived from one and has the same character and mode of action as the steroids. 2. Monoamines (biogenic amines) are made from amino acids and retain an amino group;,they include several neurotransmitters as well as hormones. (Fig. 12.21) a. The monoamine hormones include dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, melatonin, and thyroid hormone. b. Dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine are called catecholamines. 3. Peptide hormones are chains of 3 to 200 or more amino acids. a. Oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone, from the posterior pituitary, are very similar, differing only in two of their nine amino acids. (Fig. 17.14c) b. Except for dopamine, the releasing and inhibiting hormones of the hypothalamus are polypeptides. c. Most hormones of the anterior pituitary are polypeptides or glycoproteins. d. Most glycoprotein hormones have an identical alpha chain of 92 amino acids and a variable beta chain. B. All hormones are synthesized from either cholesterol or amino acids, with carbohydrate added in the case of glycoproteins. (pp. 656–660) 1. Steroid hormones are synthesized from cholesterol and differ mainly in the functional groups attached to the four-ringed steroid backbone. (Fig. 17.15) a. Although estrogen and progesterone are thought of as “female” hormones and testosterone as a “male” hormone, they are interrelated in synthesis and have roles in both sexes. 2. Peptide hormones are synthesized in the same way as any other protein. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 17 a. The gene is transcribed to form mRNA, and ribosomes translate the mRNA and assemble amino acids in the right order to make the hormone. b. The newly synthesized polypeptide is an inactive preprohormone i. The first several amino acids serve as a signal peptide that guides it into the cisterna of the rough endoplasmic reticulum. ii. Here the signal peptide is split off and the remainder is now a prohormone. c. The prohormone is transferred to the Golgi complex which may process it further and then package it for secretion. d. Insulin begins as preproinsulin. i. When the signal peptide is removed, the chain folds back on itself and forms three disulfide bridges—it is now proinsulin. ii. This is packaged into a secretory vesicle, where enzymes remove the connecting (C) peptide. iii. The remainder is now insulin, composed of two polypeptide chains totaling 51 amino acids connected to each other by two of the three disulfide bridges. (Fig. 17.16) 3. Monoamines are also made from amino acids. a. Melatonin is synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan, and the other monoamines from the amino acid tyrosine. b. Thyroid hormone is unusual in that each molecule is composed of two tyrosines. c. The synthesis, storage, and secretion of thyroxine take place as follows: (Fig. 17.17) i. Follicular cells absorb iodide ions (I–) from the blood plasma and secrete them into the follicle where the iodide is oxidized to a reactive form. ii. Meanwhile, the follicular cells synthesize thyroglobulin via the rough ER and Golgi complex and release it onto the cell surface where an enzyme at the plasma membrane adds iodine to some of its tyrosines. a. Each thyroglobin has 123 tyrosines in its amino acid chain but only 4 to 8 of them will become thyroid hormone. iii. In the lumen, tyrosines link to each other to form thyroxine (T 4), but T4 remains bound to thyroglobulin. Stored thyroglobulin forms colloid. (Fig. 17.9b) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 18 iv. When stimulated by TSH, follicular cells absorb droplets of thyroglobulin by pinocytosis. A lysosome fuses with the vesicle and releases an enzyme that liberates T 4 from the thyroglobulin. v. Thyroxine is released into the blood and binds with transport proteins that carry it to its target cells.The thyroid synthesizes a small amount (5% of total) of triiodothyronine (T 3). d. Iodine and tyrosine are combined in the follicular lumen by the following processes. (Fig. 17.18) i. An iodine atom binds to the tyrosine ring, converting it to monoiodotyrosine (MIT). ii. MIT binds a second iodine, becoming diiodotyrosine (DIT). iii. Two DITs become linked through an oxygen atom of one of their rings, forming thyroxine (T 4). The rest of the peptide chain splits away from one of the tyrosines, but the thyroxine remains temporarily bound to thyroglobulin through the other tyrosine. iv. When the cell is singaled to release thyroid hormone, the lysosomal enzyme degrades the peptide chain of thyroglobulin and releases thyroxine. e. T3 is synthesized in small amounts by the binding of an MIT and a DIT. Most T3, however, is produced in the liver and other tissues by removing an iodine from circulating T4. C. Hormone transport through the blood, which is mostly water, is a simple matter of monoamines and peptides, but the hydrophobic steroids and thyroid hormone must bind to hydrophilic transport proteins. (p. 660) 1. Albumins and globulins synthesized by the liver act as transport proteins. 2. A hormone attached to a transport protein is called bound hormone, and the one that is not attached is an unbound or free hormone. 3. Only the unbound hormone can leave a blood capillary and get to a target cell. (Fig. 17.19) 4. Unbound hormone can be broken down or removed from the blood in a few minutes, whereas bound hormone may circulate for hours to weeks. 5. Thyroid hormone binds to three transport proteins: albumin, thyretin (an albumin-like protein), and an alpha globulin names thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). a. TBG binds the greatest amount. b. More than 99% of circulating TH is bound. 6. Steroid hormones bind to globulins such as transcortin, the transport protein for cortisol.7. Aldosterone is unusual in that it has no specific transport protein but binds Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 19 weakly to albumin and others; however, 85% remains unbound and thus it has a half-life of only 20 minutes. Insight 17.2 Hormone Receptors and Therapy D. Hormones stimulate only those cells that have receptors for them, and the receptors act like switches to turn certain metabolic pathways on or off when the hormone binds to them. (pp. 660–663) 1. Receptor–hormone interactions are similar to enzyme–substrate interactions. Unlike enzymes, receptors do not chemically change their ligands; they do, however, exhibit specificity and saturation. a. Specificity means that a receptor for one hormone will not bind other hormones. b. Saturation is the condition in which all receptor molecules are occupied by hormone molecules. 2. Steroid hormones and thyroid hormone enter the target cell nucleus and act directly on the genes by activating or inhibiting transcription. a. Steroid hormones are hydrophobic and diffuse easily through the plasma membrane. b. Most pass directly into the nucleus, but glucocorticoids bind to a receptor in the cytosol, and the complex is then transported into the nucleus. c. Estrogen and progesterone both act on cells of the uterine mucosa in a way typical of steroids. i. Estrogen activates a gene for the protein that functions as the progesterone receptor. ii. Progesterone binds to these receptors later, stimulating transcription of the gene for a glycogen-synthesizing enzyme. iii. The uterine cell then synthesizes and accumulates glycogen for the nourishment of an embryo in the case of pregnancy. iv. Progesterone has no effect on these cells unless estrogen has been there earlier. d. Thyroid hormone in the T4 form has little metabolic effect, but in the target cell cytoplasm, an enzyme converts T 4 to the more potent T3. i. T3 enters the target cell nucleus and binds to receptors. (Fig. 17.20) ii. One of the genes activated by T 3 is for the enzyme Na+-K+ ATPase, the sodium–potassium pump. One of the effects of this pump is to generate heat. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 20 iii. T3 also activates transcription of genes for β-adrenergic receptors and a component of myosin, enhancing cell responsiveness to sympathetic nervous system stimulation. e. Steroids and thyroid hormones typically require several hours to days to show an effect, due to the lag time for transcription, translation, and accumulation of protein. 3. Peptides and catecholamines are hydrophilic and cannot penetrate into a target cells, so they bind to cell-surface receptors linked to second-messenger systems. (Fig. 17.19) a. Glucagon binds to receptors on the surface of a liver cell, which activates a G protein. i. This G protein in turn activates adenylate cyclase to produce cAMP, a second messenger. ii. cAMP ultimately activates enzymes that hydrolyze glycogen. (Fig. 17.21) b. Somatostatin inhibits cAMP synthesis. c. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) works through cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). d. Second messengers do not linger in the cell, but are quickly broken down. For example, cAMP is broken down by phosphodiesterase. e. Other commonly employed second messengers include diacylglycerol (diglyceride; DAG) and inositol triphosphate (IP 3). f. The DAG pathway follows the steps on the left side of Fig. 17.22: i. (1) A hormone binds to a receptor, which activates a G protein. ii. (2) The G protein migrates to a phospholipase molecule and activates it. iii. (3) Phospholipase removes the phosphate-containing group from the head of a membrane phospholipid, leaving DAG embedded in the plasma membrane. iv. (4) DAG activates protein kinase (PK) that phosphorylates enzymes. g. The IP3 pathway follows the steps on the right side of Fig. 17.22. The first two steps are the same as in the DAG pathway, and the new steps are: i. (5) The phosphate-containing group removed at step 3 is IP 3, which raises calcium concentration in the cytosol in two ways: ii. (6) IP3 opens gated channels and admits Ca2+. iii. (7) IP3 opens gated channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and releases Ca2+ from storage. Calcium, a third messenger, can have three effects: Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 21 iv. (8) Ca2+ may bind to other gated membrane channels and alter the potential or permeability. v. (9) Ca2+ may activate cytoplasmic enzymes that alter metabolism. vi. (10) Ca2+ may bind to calmodulin which in turn activates a protein kinase (step 4). h. In this way, hydrophilic hormones that cannot enter the cell can have marked effects on metabolic activity by binding to a surface receptor. i. Hormonal effects mediated through surface receptors are relatively quick because the cell does not have to synthesize new proteins. j. A hormone may employ more than one second messenger. i. ADH uses the IP3-calcium system in smooth muscle but the cAMP system in kidney tubules. k. Insulin is different in that it binds to a plasma membrane enzyme, tyrosine kinase, which directly phosphorylates cytoplasmic proteins. E. One hormone molecule can trigger synthesis of an enormous number of enzyme molecules, a mechanism called enzyme amplification. (pp. 663–664) (Fig. 17.23) 1. One glucagon molecule can ultimately result in the production of 1 billion enzyme molecules. 2. Hormones are therefore potent in very low concentrations, and target cells do not need a great number of hormone receptors. F. Target cells can modulate their sensitivity to a hormone by up-regulation and down-regulation of receptors. (p. 664) 1. In up-regulation, a cell increases the number of receptors, becoming more sensitive to a hormone. (Fig. 17.24a) 2. In down-regulation, a cell reduces its receptor number and becomes less sensitive to a hormone. (Fig. 17.24b) 3. Hormone therapy often involves long-term use of abnormally high pharmacological doses of a hormone, which may have undesirable effects. For example, hydrocortisone negatively affects bone metabolism. 4. These effects can come about in two ways: a. Excess hormone may bind to receptor sites for other, related hormones and mimic their effects. b. A target cell may convert one hormone into another, such as testosterone into estrogen. G. Hormones may interact with one another because many hormones are present in the blood at any time; their interactive effects may be grouped into three classes. (pp. 664–665) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 22 1. Synergistic effects—two or more hormones act together to produce an effect greater than the sum of their separate effects. 2. Permissive effects—one hormone enhances the target organ’s response to a second hormone secreted later, such as the effect of estrogen on up-regulation of progesterone receptors in the uterus. 3. Antagonistic effects—one hormone opposes the action of another, such as insulin and glucagon. H. Hormone clearance occurs when hormones are taken up and degraded by the liver and kidneys and then excreted in bile or urine. (p. 665) 1. The rate of hormone removal is the metabolic clearance rate (MCR). 2. The length of time required to clear 50% of the hormone from the blood is its half-life. V. Stress and Adaptation (pp. 665–666) A. Stress is any situation that upsets homeostasis and threatens an individual’s physical or emotional well-being. (p. 665) B. The body reacts to stress with the stress response or general adaptation syndrome (GAS). This typically involves elevated levels of epinephrine and glucocorticoids, especially cortisol. (p. 665) C. Hans Selye showed that GAS occurs in three stages: the alarm reaction, the stage of resistance, and the stage of exhaustion. (p. 665) D. The alarm reaction is the initial response to stress and is mediated mainly by norepinephrine from the sympathetic nervous system and epinephrine from the adrenal medulla. (p. 665) 1. These catecholamines prepare the body to take action such as when fighting or escaping. 2. The consumption of stored glycogen occurs, which is important to transition to the next stage. 3. Adosterone and angiotensin also increase, raising blood pressure and promoting water conservation. E. The stage of resistance is entered when the glycogen reserves are depleted, and the first priority is to provide alternative fuels for metabolism; cortisol dominates this stage. (pp. 665–666) 1. The hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH); the pituitary then releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)and the adrenal cortex then releases cortisol and other glucocorticoids. 2. Cortisol promotes breakdown of fat and protein into glycerol, fatty acids, and amino acids, so that the liver can perform gluconeogenesis. 3. Cortisol also inhibits glucose uptake (glucose-sparing action) and protein synthesis. a. Inhibition of protein synthesis has an adverse effect on the immune system. i. Mast cells release histamine and other inflammatory chemicals. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 23 ii. Wounds heal poorly and a person becomes susceptible to infections. iii. Ulcers may occur due to reduced resistance to bacteria and reduced secretion of gastric mucus and pancreatic bicarbonate, suppressed by epinephrine. 4. Cortisol suppresses the secretion of sex hormones. F. The stage of exhaustion sets in when the body’s fat reserves are depleted and stress overwhelms homeostasis. (p. 666) 1. This stage may be marked by rapid decline and death. 2. With fat stores gone, the body relies primarily on protein breakdown to meet energy needs, accompanied by wasting away of the muscles and weakening. 3. The adrenal cortex may stop producing glucocorticoids. 4. A state of hypertension may be the result of aldosterone. 5. Aldosterone also hastens elimination of potassium and hydrogen ions, creating a state of hypokalemia and alkalosis that can lead to nervous and muscular system dysfunctions. VI. Eicosanoids and Paracrine Signaling (p. 666) A. Paracrine messengers are chemical signals released by cells into the tissue fluid; they do not travel by way of the blood but diffuse to nearby cells in the same tissue. (p. 670) 1. Histamine is released by mast cells alongside blood cells in connective tissue, and it diffuses to the smooth muscle of the blood vessel causing dilation. 2. Nitric oxide is released by endothelial cells of the blood vessel itself and also causes vasodilation. 3. In the pancreas, somatostatin released by delta cells acts as a paracrine signal when it diffuses to alpha and beta cells, inhibiting their secretion of glucagon and insulin. 4. Catecholamines diffuse from adrenal medulla to cortex to stimulate corticosterone secretion. B. The eicosanoids are an important family of paracrine secretions. (p. 666) 1. These compounds have 20-carbon backbones derived from arachidonic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid. 2. Some peptide hormones and other stimuli liberate arachidonic acid from a phospholipid of the plasma membrane, and then two enzymes convert it to eicosanoids. (Fig. 17.25) a. Lipoxygenase helps convert arachidonic acid to leukotrienes, eidcosanoids that mediate allergic and inflammatory reactions. b. Cyclooxygenase converts arachidonic acid to three other types of eicosanoids. i. Prostacyclin is produced by walls of blood vessels, where it inhibits blood clotting and vasoconstriction. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 24 ii. Thromboxanes are produced by platelets and override prostacyclin to stimulate vasoconstriction and clotting. iii. Prostaglandins are a diverse group of eicosanoids that contain a five-sided ring structure and were first found in semen and the prostate gland. They are named PG plus a third letter indicating type of ring structure, plus a subscript indicating number of double bonds, for example PGF2α. (Fig. 17.25) (Table 17.7) 3. The action of some familiar drugs such as NSAIDs is due to their effect on the pathways of eicosanoid synthesis. Insight 17.3 Anti-Inflammatory Drugs VII. Endocrine Disorders (pp. 667–671) A. Hyposecretion is inadequate hormone release, and hypersecretion is excessive hormone release. (p. 668) 1. If the hypothalamo–hypophyseal tract is severed, such as by a fractured sphenoid, transport of oxytocin and ADH to the posterior pituitary is disrupted, leading to diabetes insipidus. 2. Autoimmune diseases also can lead to hormone hyposecretion when endocrine cells are attacked. This is one of the causes of diabetes mellitus. 3. Some tumors result in overgrowth of functional endocrine tissue and hypersecretion. A pheochromocytoma, a tumor of the adrenal medulla, can cause hypersecretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine. (Table 17.8) 4. Some autoimmune disorders can cause hypersecretion, such as toxic goiter (Graves disease. (Table 17.8) B. Pituitary disorders affect growth. (p. 668) 1. Hypersecretion of growth hormone (GH) in adults causes acromegaly. (Fig. 17.26) 2. GH hypersecretion in childhood or adolescence causes gigantism. 3. GH hyposecretion in childhood or adolescence causes pituitary dwarfism. (Table 17.8) a. Pituitary dwarfism is rarer now that genetically engineered human GH is available. C. Thyroid and parathyroid disorders are discussed together because of these glands’ proximity. (pp. 668–669) 1. Congenital hypothyroidism is hyposecretion of TH present from birth. 2. Severe or prolonged adult hypothyroidism can cause myxedema. Both congenital and adult hypothyroidism can be treated with oral thyroid hormone. 3. A goiter is a pathological enlargement of the thyroid. a. Endemic goiter is due to a dietary deficiency of iodine, required for TH synthesis. (Fig. 17.27) Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 25 b. Without TH, the pituitary produces extra TSH, and the thyroid gland undergoes hypertrophy. 4. The parathyroids are sometimes accidentally removed in thyroid surgery. a. Without hormone replacement, hypoparathyroidism causes a rapid decline in calcium levels leading to fatal tetany within 3 or 4 days. b. Hyperparathyroidism usually results from a tumor. It causes bone to become soft and fragile, and raises the blood levels of calcium and phosphate, promoting renal calculi (kidney stones) formed of calcium phosphate. D. Adrenal disorders include Cushing syndrome and adrenogenital syndrome. (p. 669) 1. Cushing syndrome is excess cortisol secretion due to any of several causes, including ACTH hypersecretion by the pituitary, ACTH-secreting tumors, or hyperactivity of the adrenal cortex. 2. Cushing syndrome disrupts carbohydrate and protein metabolism, leading to hyperglycemia, hypertension, muscle weakness, and edema. a. Muscle and bone mass are lost as protein is catabolized. b. Abnormal fat deposition between the shoulders or in the face may also occur, and these may also be effects of long-term hydrocortisone therapy. (Fig. 17.28) 3. Adrenogenical syndrome (AGS) is the hypersecretion of adrenal androgens and commonly accompanies Cushing syndrome. a. In children, AGS often causes enlargement of the penis or clitoris and the premature onset of puberty. b. Prenatal AGS can result in newborn girls exhibiting masculinized genitalia and being misidentified as boys. (Fig. 17.29) c. In women, AGS produces masculinizing effects such as increased body hair, deepening of the voice, and beard growth. E. Diabetes mellitus is the world’s most prevalent metabolic disease, occurring in about 7% of the U.S. population and even more in Scandinavia and the Pacific Islands (pp. 670–671) 1. It is the leading cause of adult blindness, renal failure, gangrene, and limb amputations. 2. Diabetes mellitus (DM) can be defined as a disruption of carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism resulting from hyposecretion or inaction of insulin. a. Classic signs are the three polys: polyuria (excessive urine), polydipsia (intense thirst), and polyphagia (ravenous hunger). b. Three further clinical signs are revealed by blood and urine tests: hyperglycemia (elevated blood glucose), glycosuria (glucose in the urine, from which the disease gets its name), and ketonuria (ketones in the urine). 3. Normally the kidneys remove glucose from the urine and return it to the blood, via glucose transporters (carrier-mediated transport). Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 26 4. In DM, the amount of glucose saturates the glucose transporters, and the excess glucose passes through into the urine. 5. Glucose and ketones in urine raise osmolarity, causing osmotic diuresis—water remains in the tubules. 6. A person with untreated DM may pass 10 to 15 L of urine per day, compared with 1 or 2 L normally. 7. There are two forms of DM: type 1 (formerly juvenile or insulin-dependent) and type 2 (formerly adult or non-insulin-dependent). The older terms have been abandoned because they are misleading given current knowledge. 8. Type 1 DM accounts for 5% to 10% of all cases in the U.S. a. Several genes have been identified that predispose a person to type 1 DM. b. When a genetically susceptible individual is infected by certain viruses, the body produces autoantibodies that destroy pancreatic beta cells. c. When 80% to 90% of the beta cells are gone, insulin falls to a critically low level and hyperglycemia occurs. d. Victims require insulin to survive, usually by injection, and meal planning, exercise, and self-monitoring of blood glucose are aspects of treatment. e. It is usually diagnosed before age 30, but may occur later. 9. Type 2 DM accounts for 90% to 95% of all cases. a. The chief problem is insulin resistance—unresponsiveness of the target cells to the hormones. b. There is clear evidence of a hereditary component because of differences in incidence from one ethnic group to another. i. Incidence is high among people of Native American, Hispanic, and Asian descent. ii. It also has a tendency to run in families and has high concordance in genetically identical twins. c. Age, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle are important risk factors. i. As muscle mass is replaced with fat, a person become less able to regulate blood glucose level. d. Type 2 DM develops slowly and is usually diagnosed after age 40, but is becoming more prevalent in young people because of childhood obesity. e. Another factor besides the effects of muscle loss is that adipose tissue secretes chemical signals that directly interfere with glucose transport into most cells. f. Type 2 DM can often be successfully managed through a weight loss program of diet and exercise; if these prove inadequate, insulin therapy is also employed. 10. Pathogenesis results from a combination of cell starvation and hyperglycemia. Saladin Outline Ch.17 Page 27 a. The body metabolizes fat and protein when cells cannot absorb glucose. b. Prior to insulin therapy, victims wasted away in pain, hunger, and despair. Children lived less than 1 year after diagnosis. c. Rapid fat catabolism elevates blood levels of free fatty acids and their breakdown products, the ketone bodies, and leads to ketonuria. i. Ketonuria flushes Na+ and K+ from the body, creating electrolyte deficiencies. ii. Ketones in the blood lower the pH, causing ketoacidosis and a deep gasping breathing called Kussmaul respiration, typical of terminal diabetes. Ketoacidosis also produces diabetic coma. d. DM leads to long-term degenerative cardiovascular disease. i. Chronic hyperglycemia has negative effects on small to medium blood vessels (microvascular disease) including atherosclerosis. ii. Two common complications are blindness and renal failure, brought on by arterial degeneration in retinas and kidneys. iii. Death by renal failure is more common in type 1 than in type 2. iv. In type 2, death due to heart failure from coronary artery disease is more common. e. DM leads to long-term degenerative neurological disease. i. Diabetic neuropathy is nerve damage resulting from impoverished blood flow. ii. This can lead to loss of sensation, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. iii. Microvascular disease in the skin results in poor healing, so that even a minor break easily becomes infected and even gangrenous, especially in the feet. iv. Neuropathy may make a person unaware of skin lesions so that they are not treated quickly. 11. Other types of diabetes exist, such as diabetes insipidus, described earlier. Insight 17.4 The Discovery of Insulin Connective Issues: Endocrine System Interactions Cross References Additional information on topics mentioned in Chapter 17 can be found in the chapters listed below. Chapter 1: Oxytocin and positive feedback cycles Chapter 2: Enzyme–substrate interactions Chapter 3: Effects of the sodium–potassium pump Saladin Outline Ch.17 Chapter 5: Exocrine glands Chapter 7: Mechanisms of parathyroid hormone action Chapter 12: Monoamines (biogenic amines) as neurotransmitters Chapter 14: Hypothalamus structure and function Chapter 18: Prostacyclin and thromboxane action Chapter 21: The histology and immune functions of the thymus Chapter 21: Eicosanoids and allergic and inflammatory reactions Chapter 23: Other forms of diabetes Chapter 26: Leptin and enteric hormone action Chapters 27, 28: Anatomy of gonads Chapter 28: Functions of estradiol and progesterone Page 28