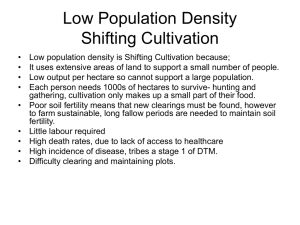

AN EVALUATION OF THE CONCEPT OF CARRYING CAPACITY John M . Street University of H m a i i T H E calculation of the carrying capacity of the environment of some particular primitive society and the improvisation of formulae for the determination of carrying capacities have been fairly common objectives of anthropologists and cultural geographers in recent years. According to William Allan, a student of African husbandry, whose definition of carrying capacity seems to have the greatest currency among anthropologists and geographer investigators of primitive agriculturalists, it is “the maximum number of people that a given land area will maintain in perpetuity under a given system of usage without land degradation setting in.” (I) L. G. Loffler, (2) H. C. Conklin, (3) H. C. Brookfield (4) and others imply that “a given system of usage” involves: unvarying technology and crop patterns; qualitatively and quantitatively constant per capita food consumption. Conklin and Brookfield to name but two out of many, fail to make any serious effort t o determine whether land degradation is setting in. Unfortunately, the assumptions of technological and gastronomic stagnation mentioned above depart so markedly from reality as to seriously diminish the utility of the computed population density values. Not only do primitive peoples readily adopt new crops, new tools, new techniques-as is attested by the rapid diffusion of maize, Xanthosoma spp., and steel in New Guinea, of watermelons, horses, and bananas in the New World, of maize, manioc and papayas in Africa-under the pressure of circumstances, they may practice techniques already known, but not previously utilized. W e may cite a number of examples: Allan, in describing the intensive agriculture of Wakara Island, Lake Victoria wrote, “faced with the problem of maintaining permanent cultivation-the Kara adopted the expedient of manuring. There is nothing remarkable in this; it is a mistake to suppose that African people are ignorant of the use of manure or that its value as a soil fertilizer is beyond their understanding.” (5) At first hand, I have observed in the Bismarck Mountains of New Guinea, a t the village of Kompiai, war refugees, whose traditional system was slash and burn, busily spading sod. Though they prefer the ancestral system, circumstances obliged them to employ another well-known, but laborious and distasteful system. (6) Ester Boserup deals at length with the topic of agrarian change under population pressure. “Thus the new approach to agricultural development which is signalled by the concept of frequency of cropping draws the attention to the effects upon agricultural technology which are likely to result from population changes. This is a sharp contrast to the usual approach which takes agricultural technology as a largely autonomous factor in relation to population changes.” (7) The assumption of an unvarying crop pattern which is implicit in “a given system of usage” is clearly a t odds with empirical fact. As people press upon their resources they tend to raise those crops that give a high yield as related to area available for cropping-not necessarily those that they prefer to eat nor those that they formerly ate. Many inhabitants of south China and Okinawa who prefer rice and whose ancestors subsisted o n rice derive sustenance from sweet potatoes which outyield other upland crops. By the same token the quality and quantity of per caput food consumption tend to decline with crowding upon the land. The inhabitants of the limestone country near Jogjakarta on Java have in recent times changed their diet from rice and maize to manioc and concurrently have developed widespread protein deficiency symptoms. (8) In most of the studies reviewed the criterion of the maintenance of the resource base is treated perfunctorily. R. L. Carneiro, in a study of an Amazonian village states that, “the number of years the plot must lie fallow before it can be recultivated” is the equivalent of the length of fallow required to prevent any long term impairment of the soil. (9) I infer that he determined “the number of years the plot must lie fallow” simply by calculating the 104 VOL. XXI, NUMBER 2, MARCH,1969 average fallow practiced by his villagers. There is no indication that he made any serious effort to find out whether soil degradation was occurring. R. F. Salisbury, in a report on the Siane of the New Guinea highlands, writes, “the technique of cultivation and the acreages used would support an equilibrium analysis projecting the present both forward and backward-.” “The ratio of cultivation to fallow would clearly indicate that no progressive impoverishment of the land need occur.” (10) Alas, Salisbury fails to offer any evidence to support his assertion that the land is not being impoverished. I have the uneasy feeling that he has simply equated contemporary fallowing practice with that requisite to soil conservation. H. C. Conklin, in his treatise on Hanunoo agriculture on the island of Mindoro in the Philippines works out an “estimate of the critical carrying capacity of the Yagaw area through time.” (11) Again current fallowing practice is equated with the ideal. True, he does state that the community under study seems to have been stable through time, through references to erosion and the existence of savannas suggest past, and possibly present, instability. Harold Brookfield, in a study on New Guinea’s upper Chimbu Valley, a region of precipitous slopes where rural population densities approach six hundred per square mile, once more identifies permissible fallowing practice with the contemporary mean for purposes of estimating carrying capacity. He justifies this procedure with the comment, “there is only limited evidence to suggest that active soil degradation is taking place in Chimbu today-.” “We may thus assume, in the absence of contrary data, that the values we employ here are reasonable.” (12) In 1956, seven years before Brookfield‘s book was published, District Agricultural Officer J. W. Barrie wrote of the Chimbu, “with reference to the negative factor of diminishing land potential there is ample evidence to illustrate that on the steeper slopes the practice of shifting cultivation is resulting in soil loss and soil nutrient depletion. Crop yields are decreasing, denudation is apparent, loss and degradation of the soil is (sic) widespread.” (13) I tramped the trails of the Chimbu in October, 1964, and saw numerous unmistakable signs of environmental deterioration, to wit: many land 105 slips, hard soil with poor structure, sediment-laden streams, rill wash, exposed subsoil. In a recent commentary on the use of the methods of ecological potential in estimating the aboriginal American population, Peter Kunstadter states: “One underlying assumption of the whole argument is that human populations will fill to the point of equilibrium the ecological space available to them.” “Finding that an isolated pristine human population did not conform to the equilibrium model might dispel some of the mysticism surrounding the idea that primitive man is always in balance with nature, while modern man despoils and upsets that balance.” (14) Of course we do have evidence of “pristine” human populations having despoiled their environment, for example, the Chimbu discussed in this paper or the Kara referred to in Allan’s 1965 work. Determination of that fallow period which allows maximum population density consistent with maintenance of the soil resource is difficult if not impossible. Deterioration of the land is a cumulative process and short term changes may be so slight as to be exceeded by errors in measurement. Cowgill in a study of soil fertility and the ancient Maya attempted to determine the rate of soil recovery under bush fallow by means of chemical analyses of randomly chosen fields which had been under fallow for various lengths of time. ( 1 5 ) Not only did she not know the nutrient status of these fields at the time of garden abandonment, but the measurement of changes in available phosphorus would be suspect even if the nutrient status were known. Referring to the work of Nye and Greenland on T h e Soil under Shifting Cultiuation I found that “the value of soil analysis as an index of fertility decline is limited because of difficulties in interpretation. The conventional measurements-tell us about the amounts of nutrients present, but not directly about their ‘availability-.” (16) “Changes in total soil phosphorus during a period of cropping are relatively so small that they cannot normally be measured.” “These authors have not found any generally valid method of estimating the availability of soil phosphorus.” (I 7) Further to confound the reckoner of the soil fertility budget there exist only vague 106 THE PROFESSIONAL notions of the rate of formation of most tropical soils. And to quote once more from Nye and Greenland, “Essential knowledge is also lacking on the extent of leaching losses particularly during the cropping period.” ( I 8) A deficiency common in calculations of carrying capacity is the assumption that, as the intensity of land use increases, the incidence of weeds, diseases, harmful insects, human and animal parasites will remain constant, whereas there is a tendency for pests to increase more rapidly than crop acreage and human numbers. Propinquity and long-continued cropping or residence in a given place favor pests. W e should not allow the elusiveness of “long-term carrying capacity” to distract us from a very proper concern with the ecological soundness of the relationship between our chosen people and the land. Let us address ourselves to the question posed by Spencer, “What does the practice of shifting cultivation do to the landscape and the environment?” (19) Several investigators have approached this problem in a most constructive manner. I shall cite a few. J. D. Freeman in a thorough and logical study of the Sea Dayaks in Borneo ascertained that cropping for two years in succession raised considerable hazards of erosion and of displacement of forest by a highly combustible savanna o f lmperuta cylindricu, whereas cropping for but one year coupled with a fallow of 11-14 years markedly lessened these hazards. (20) L. G. Loffler working in the Chittagong Hills assembled data on yields per unit area, fallow land included, showing that o u t m t of a territorv rises then with progressive shortening of the GEOGRAPHER fallow period. (21) David Simonett used air photos to measure the incidence of landslides as a function of vegetation cover in the eastern highlands of New Guinea, finding a higher frequency in anthropogenic grasslands than in forests. (22) A pitfall that often traps enquirers into the ecology of shifting agriculturalists is the tendency to become enamored of the object of their scrutiny; the swiddeners appear to be so self-sustaining, so well integrated with their environment, so in harmony with nature that it is hard to believe that they may be damaging their resource base. W. R. Geddes, who studied the Mia0 of northern Thailand, staunchly maintained that his people and primitives in general would not fire the savannas simply for pleasure. (23) Unfortunately, my observations and those of many botanists and foresters are at variance with this belief. Much research is still needed to indicate the effect of the shifting cultivator on his environment: measurement of erosion, measurement of leaching, measurement of yields under diverse systems of land rnanagement and in various environments. T o date anthropologists and geographers have confined themselves to field studies with relatively short periods of direct observation, while experimental studies of tropical subsistence agriculture have been few and often ill-structured. T o achieve progress it is necessary to conduct experiments on replicated plots, to control variables other than those under investigation, to continue observations over a long span of time, to describe the experiments in sufficient detail so that other workers in the field may properly evaluate them. * * * Allan, William. “Studies in African Land Usage in Northern Rhodesia.” Rhodes Livingstone Papers, No. 15, 1949. Loffler, Lorenz G. “Bodenbedarf und Ertragsfaktor im Brandrodungsbau.” Tribus, Vol. 9, 1960, pp. 3943. Conklin, Harold C. Hanumoo Agriculture. FAO, Rome, 1957, p. 146. Brookfield, Harold C. and Paula Brown. Struggle f o r Lund; Agriczcltiire und Group Territories among (5) (6) (7) the Chimbu o f the New Guinea Highlands. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1963. Allan, William. The African Husbandmen. London, 1965, p. 200. William Clarke discusses population pressure and resulting technological change in the general area of Kompiai in “From Extensive to Intensive Cultivation: a Succession from New Guinea.” Ethnology, Vol. 5 , 1966, pp. 347-359. Boserup, Ester. T h e Economics o f XXI, N U M I ~ E2,R MAIICH,1969 107 Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. Aldine Press, Chicago, 1765, p. 14. Bailey, K. V. and Merle J. “Cause and Effect of Soil Erosion in Indonesia.’’ Symposium on the lmpact of Primitive Man on Humid Tropics Vegetation. UNESCO, Goroka, Sept. 1960, p. 272. Carneiro, Robert L. “Slash and Burn Agriculture, a Closer Look at its Implications for Settlement Patterns.” Selected Papers of the 5th International Congress o f Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1960, p. 231. Salisbury, R. F. “Changes in Land Use and Tenure among the Siane of the New Guinea Highlands (1952Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 5, 1961) No. 1, May, 1964, pp. 1-10, p. 10. Conklin, op. cit., p. 146. Brookfield and Brown, 09. cit., p. 123. Barrie, J. W. “Population-Land Investigation in the Chimbu District.” Papua and New Guinea Agricultural Journal, Vol. 11, No. 2, October, 1956, p. 51. Kunstadter, Peter. Current Anthropology. Vol. 7, No. 4, Oct. 1965, p. 437. Cowgill, Ursula M. “Soil Fertility of the Ancient Maya.” Trans. o f the Conn. Acud. o f Arts and Sciences, Vol. 42, October 1961, p. 45. Nye, P. H. and D. J. Greenland. T h e Soil under Shifting Cultivation. Commonwealth Bureau of Soils, Technical Communication No. 51, 1960, p. 98. lbid., p. 112. Ibid., p. 119. Spencer, J. E. “Introduction.” Symposium: Effects of Shifting Agriculture on Natural Resources with Special Reference to Problems in Southeast Asia. Proceedings of the 9th Pacific Science Congress, Vol. 7, Bangkok, 1759, p. 51. Freeman, J. D. Ibun Agriculture. London, 1955, p. 130. Loffler, op. cit., p. 42. Simonett, David S. “Soil Erosion in the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea.” Paper presented at the national meeting of the Soil Science Society of America, 1963. Geddes, W. R. “Discussion.” S y m posium on the Impact o f Primitive M a n on Humid Tropics Vegetation. UNESCO, Goroka, Sept. 1963, pp. 135, 143. The newest map title in the Bureau of the Census GE-50 series, No. 24, is “Families in Poverty Areas for Selected Cities of the United States: 1960.” Circle sizes show the number of families in cities, and families in poverty and non-poverty city areas expressed as portions of total numbers of families in the city. The price of the map at the Supt. of Documents is 50 cents. ada: A Geographical Interpretation, edited by John Warkentin. .” Frederick Watts, editor of the Canadian Geographer and staff member at the University of Toronto, died on January 2. After completing his M.A. degree at Syracuse University he lectured at the University of Manitoba. His geographical interest centered mainly on the field of climatology, and he contributed the section on “Climate, Vegetation, and Soil” to the volume, Can- A recent newsletter announces that the sixth international symposium on remote sensing of environment is to be held at the University of Michigan October 14-16, 1969. The registration fee, which includes the cost of the published proceedings, will be $30. Further information may be obtained from Extension Service, Conference Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 48104. Leslie J. King of Ohio State University is the director of a NSF grant to support a summer institute for college teachers in the social science fields during the summer of 1969.