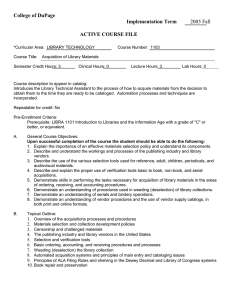

European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, 2006 Ó 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 0263-2373 $32.00 doi:10.1016/j.emj.2006.08.002 Determinants of International Acquisition Success: Lessons from FirstGroup in North America CATRIONA DUNCAN, Marks & Spencer MONIA MTAR, University of Edinburgh This paper proposes a process model of key determinants of international acquisitions success, drawing on strategic management, organisational and learning theories. The validity of this model is tested through the analysis of the successful acquisition by FirstGroup, the UK’s largest provider of public transport, of Ryder, the second largest player in the US School Bus industry. The case demonstrates the importance of identifying a target in a market sector in which the UK has a competitive advantage and which fits well with the acquirer’s core business. Going against the grain of theory on integration, findings also show that, under certain conditions, low integration can yield significant benefits, leaving further integration as an option for the future, to create further value. The impact of cultural fit on acquisition performance is found to be dependent upon the level of integration adopted. The capacity of the acquirer to learn from previous acquisition experience is critical in ensuring the successful management of both pre- and post-acquisition phases. The theoretical and practical implications of the findings are discussed. Ó 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction Keywords: Cross-border mergers & acquisitions, Post-merger integration, International strategy, British multinationals, Services industry, FirstGroup This paper aims to address this gap. It proposes a process and integrative model of the determinants of cross-border acquisition success, drawing on concepts of strategic management, organisational and learning theories. The validity of this model is tested through an in-depth analysis of the successful entry 396 In spite of a dramatic growth in the number of crossborder acquisitions over the last decade, there is limited research on the key factors that affect their success. In a recent review of the literature on cross-border M & As, Shimizu et al. (2004: 345) argue: An important research issue involves the explanatory variables for (cross-border M & As) wealth creation. The authors (2004: 345) note that the limited literature that exists on international acquisition performance has mainly drawn on the fields of economics and finance, overlooking factors of synergy and strategy, and that a firm-level focus is needed in order to uncover the mechanisms at play in the success of M & As. We also believe that research on international acquisitions which draws on other theories, such as cross-cultural and learning perspectives, has not systematically considered the strategic and/or performance dimensions of M & As. Furthermore, more attention needs to be given to important processes such as integration (Shimizu et al., 2004: 324). European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS of FirstGroup, the UK’s largest provider of public transport, to the North American market. In 1999, this Group acquired Ryder Transportation and immediately became the second largest player in the US School Bus industry. There are significant commercial links between the UK and North America, yet the U.S. is still seen as a graveyard for UK companies wishing to expand their operations. Understanding the reasons behind FirstGroup’s success is therefore of interest. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on the public transport industry. Yet, like many other services industries, this sector is increasingly becoming international. The UK is now home to five large quoted companies who are global players in the public transport arena. This has been brought about by the comparatively early privatisation of the industry, which has given these organisations a distinct competitive advantage and they are now leading the globalisation of the industry. This paper opens with the presentation of a model of critical success factors in cross-border acquisitions. The significance of these factors to FirstGroup’s North American acquisition is then assessed in detail as part of the case study, and these findings are compared and contrasted to current academic thinking on these issues. In the concluding section, the theoretical and managerial implications are discussed, and further research directions suggested. A Model of Success Factors in Cross-Border Acquisitions A model of critical success factors in cross-border acquisitions is proposed, based on an in-depth review of the relevant literature. The model draws on strategic management, organisational and learning theories. Research on acquisitions has shown that acquisition performance is the outcome of strategic and organisational variables (e.g. Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999). Learning theory is another influential perspective for explaining acquisition performance (e.g. Very and Schweiger, 2001). We selected variables from those three perspectives that most commonly appear in the literature as critical for acquisition performance, and that we believe will require greater emphasis in an international, as opposed to a domestic, acquisition: v Acquiring Firm’s Previous Experience v Strategic Fit v Focus On Core Business v Cultural Fit v Integration Process Acquisition Each of those factors will now be examined in detail. Previous Acquisition Experience A company’s previous acquisition experience can be identified as a factor for success (Hitt et al., 1998; Hubbard, 2001: 13–14; Very and Schweiger, 2001). While no two acquisitions are the same (Clemente and Greenspan, 1998: 157), the process of all acquisitions is similar. Experience with regards to acquisitions can be beneficial for two main reasons. Firstly, many of the processes are recurrent, and the firm will have honed key skills through previous experience. Secondly, firms will be more knowledgeable about issues connected to an acquisition, such as integration and cultural issues, and will have learnt lessons from past approaches. Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991: 51–52) identify the similarity of acquisitions, through firms using a standardised decision process and discipline for their capital appropriations. They (1991: 52–55) also highlight the differences between acquisitions, such as their sporadic nature, the dissimilarity from managers’ regular experiences, the opportunistic nature and the speed with which decisions must be made. In a similar vein, Hubbard (2001: 14) identifies the process issues that can cause an acquisition to fail. Hubbard argues that organisations, which have honed these processes through multiple acquisitions, stand a much better chance of achieving success. Hitt et al. (1998: 100) also note that two-thirds of the successful firms they examined had ‘considerable experience in implementing change in the years prior to the acquisition’. The experience of confronting a complex situation resulted in the firm being ‘more flexible, with developed adaptation skills’, and being more capable in dealing with an acquisition. Hitt et al. (1998: 102) also identify that ‘careful and deliberate selection of target firms and conduct of negotiations’ is critical as it ‘reduces the probability of paying a premium’. This is a skill that is undoubtedly developed through previous acquisition experience, as shown by Very and Schweiger (2001). However, this process will be affected by the acquirer’s experience of the target country (Very and Schweiger, 2001). Experience alone is not sufficient to ensure acquisition success (Finkelstein and Haleblian, 2002; Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999; Hayward, 2002). A vital practice in making previous acquisition experience a key factor for future acquisition success is learning from that experience. Haspelagh and Jemison (1991: 88–89) argue that for learning to occur, companies must have formal acquisition review mechanisms in place. The nature of prior acquisition experience will also influence firms’ ability to learn (Finkelstein and Haleblian, 2002; Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999; Hayward, 2002). How experienced acquirers learn and apply their knowledge to subsequent deals has seldom been investigated in an international context (Shimizu European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 397 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS et al., 2004: 335). The examination of this variable therefore departs from the literature. Strategic Fit The strategic fit of the acquisition is critical for capitalising on mutual synergies, a key point that will be explored below in Focus on Core Business. In this section however, the business philosophies of the two entities will be considered (Hubbard, 2001: 14). Child et al. (2001: 9) describe M & As as ‘among the most important strategic decisions companies ever make’. With this in mind Haspelagh and Jemison (1991: 32) define the impact of acquisitions in terms of their contribution to corporate-level strategy, ‘Acquisitions can deepen the firm’s presence in an existing domain; they can broaden that domain in terms of products, markets or capabilities; or they can bring the company into entirely new areas’. However, this acquisition result must fit with the overall corporate strategy of the acquirer. Similarly Hubbard (2001: 56) explains that the acquired company has to be aligned with the strategic objective of the acquirer, whether that is market penetration, vertical expansion or market entry for example. Haspelagh and Jemison (1991: 9) identify maintaining consistency with the company’s strategy as one of the major challenges in managing an acquisition, and a problem that has to be continually addressed. Focus on Core Business An important element of strategic fit is the degree of diversification pursued by the acquirer. Acquiring a company within a purchaser’s core business has been identified as a factor that impacts international acquisition performance. Continuing to focus on the acquiring firm’s core business helps to ‘maintain its strengths and to hold or gain a long-term competitive advantage’ (Hitt et al., 1998: 102). Hitt et al. argue that acquiring a core business, such as an active competitor or business in the same industry but operating in a different geographical region, can result in the creation of positive synergy. The trend of stock markets discounting the shares of conglomerates (De Wit and Meyer, 2004: 603) illustrates that while diversification allows firms to protect themselves against poor returns in certain areas of the business, unrelated diversification is accompanied by ‘lower financial performance, lower capital productivity, higher market-related risks and a higher degree of variance in performance’ (e.g. Shrivastava, 1986: 65). Shareholders are eager to see organisations achieving economies of scale and scope, and this can be achieved more readily by maintaining a focus on the core businesses. However, Hopkins (2002: 91) argues that expanding into additional industries, allows a firm to fully exploit 398 a core competence, and create a competitive advantage. This decision between expanding into additional industries, or expanding globally to fully exploit core competence is very dependent on the industry within which the firm operates. The key issue however, is the degree of diversification. Related diversification, which consists of expanding into related industries to gain market power, permits a focus on core business to be maintained, while strategic objectives can also be met. Whilst the role of relatedness has been extensively studied in the strategy literature on domestic acquisitions, it has seldom been studied in the context of international acquisitions, an exception being a study by Datta and Puia (1995) who found inconclusive evidence. Cultural Fit Culture is a primary factor of overall acquisition success (e.g. Cartwright and Cooper, 1992: 14) and this is particularly so when considering an international acquisition. As Child et al. (2001: 17) explain, ‘the sensitivity of post-acquisition management increases when it is cross-border in scope’, with acquirer and acquired ‘bearing different management philosophies and practices’. Differences can result from either national or organisational cultures (e.g. Barkema et al., 1996; Calori et al., 1994; Child et al., 2001; Weber et al., 1996), organisational culture being firm specific and strongly influenced by the company’s history. As culture is intangible (Clemente and Greenspan, 1998: 178), it is a very difficult concept to evaluate. With an acquisition there are two distinct organisational cultures to understand. A detailed analysis must be conducted to avoid ‘culture clashes’ that can destroy alliances (Clemente and Greenspan, 1998: 178). Similarly, Calori et al. (1994: 361) state that ‘differences in organizational culture and management practices between merging firms may be sources of conflict’ resulting in the benefits of the merger not being fully realised. Differences in management values and practices between nations have been well documented (e.g. Chandler, 1986; Hofstede, 1980). Examining UK and US management, we can gain an understanding of some of these contrasts. UK and US styles have been described as some of the most similar (e.g. Hofstede, 1980). The UK and the US’ similarities stem from shared cultural traditions, and Britain’s long-term exposure to the US influence (Lawrence, 1996: 41). However, many fundamental differences have also been noted, for instance with regard to conflict resolution and management styles (Lawrence, 1996: 41). Consequently, in the case of international acquisitions, there are two separate national cultures to assimilate, along with internal organisational European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS cultures. This results in a greater possibility of incompatibility between the acquirer and the acquired. tors and operating performance measures, but critics argue that financial performance alone is not sufficient to account for acquisition performance. Culture has serious implications for the integration of a cross-border acquisition, and the company’s subsequent performance. Norburn and Schoenberg (1994, cited in Child et al., 2001: 27) found that ‘65 per cent of those acquirers who had experienced serious problems with post-acquisition integration said that these difficulties had been due to cultural differences’. Cultural fit is therefore a vital success factor for international acquisitions. In this paper, we examine changes in key financial indicators of the acquired firm since the take-over. We also adopt Larsson and Finkelstein (1999) concept of ‘synergy realisation’ defined as: ‘the actual net benefits. . . created by the interaction of two firms involved in a merger or acquisition’ (Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999: 3). This measure tracks all the major types of synergy sources in acquisitions. Although this indicator is more subjective than financial measures, by capturing the benefits which have actually taken place post-acquisition and which have solely resulted from the combination of two firms, it gives a more accurate picture of value creation in acquisitions (Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999: 4). Integration ‘The integration process is key to making acquisitions work.’ (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991: 105). They argue that ‘not until the two firms come together and begin to work toward the acquisition’s purpose can value be created’. The integration of two distinct firms, with separate cultures, as discussed above, is challenging. There are a range of hurdles associated with the integration process, the authors have identified three recurring problems as determinism, value destruction and leadership vacuum (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991: 122). Successful firms are able to overcome these problems, through management being able to quickly recognise and deal with them. In a similar vein, Shrivastave (1986: 65) claims that, key to a firm’s acquisition long-term success, is ‘how well one integrates the business after the merger’. However, Child et al. (2001: 95) argue that it is not how well the business is integrated, but that it is integrated at an appropriate level, ‘an inappropriate level of integration might be detrimental.’ Whilst Child et al. (2001: 96–97) find that an acquirer can sit anywhere on a ‘spectrum of integration’ ranging from a low level, through partially integrated situations, to those where integration is almost total, Hubbard (2001: 57) has found that generally firms choose one of four degrees of integration: total autonomy, restructuring followed by financial controls, centralization or integration of key functions and full integration. As illustrated, the level of integration is a well-documented aspect of the integration process, however the actual process of integration is largely omitted within the existing literature, and is a concept that will be examined within the case study. Relationships Among Variables and Acquisition Success As none of these factors can be taken in isolation in understanding successful cross-border acquisition, we now propose a process model that shows how their relationships constitute key success factors for cross-border acquisitions (Figure 1). Based on the above arguments, previous acquisition experience will positively affect acquisition success by helping ensure the presence of all four other antecedents to acquisition performance: strategic fit, focus on core business, cultural fit and integration. The validity of the model is now tested through the case study of FirstGroup’s North American acquisition. The Method This research examines one company within the Public Transport Industry, exploring its acquisition success in North America. This company is Previous Acquisition Experience Strategic Fit Acquisition Success Post-acquisition performance has been assessed from a variety of perspectives in the literature, and what constitutes appropriate criteria for measuring success is debatable (for a recent review, see Sudarsanam, 2003: 63-89). Studies adopting a financial perspective have examined stock market returns-based indica- Integration Cultural Fit Focus on Core Business Acquisition Success Figure 1 Model of Key Success Factors in CrossBorder Acquisitions European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 399 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS FirstGroup, who are the largest public transport providers in the UK (FirstGroup Company Information). In recent years the public transport industry structure has changed dramatically, and a trend has emerged in which this traditionally national industry is becoming increasingly global. UK companies are playing a leading role in the globalisation of the industry. Yet, there is a distinct lack of research documenting those events. Due to the nature of this research project, a case study approach was selected, permitting a fuller understanding of the context and processes being enacted (Yin, 1994). Rather than testing any specific hypothesis, this sharp focus on one explanatory case study allowed an in-depth insight into the organisation and the acquisition process. Adopting the use of a case study also made it possible to provide a dynamic account of events, and illustrate how factors interact over time. Data Collection and Analysis A combination of in-depth interviews with key executives and extensive archival data was used to construct the case study. The length of the integration period investigated is five years, and spans the preand post-acquisition phases. Interviews Based on preliminary documentary analysis, individuals who played a key role in the North American acquisition, were identified for interview. Those interviewed were as follows: FirstGroup Chief Executive (CEO), FirstGroup former Business Change Director, FirstGroup Finance Director (FD), FirstGroup Chief Operating Officer (COO) and the VicePresident Maintenance of the School Bus Division of First America. The nature of their involvement in the acquisition is detailed in Table 1. Interviewing individuals across a range of functions enabled to Table 1 build a complete picture of the acquisition process, and ensured that, for each issue investigated, the views of multiple respondents were collected. The interview schedule was semi-structured, encouraging an extensive and descriptive answer, and allowing any key points, which were raised by the interviewee to be explored in greater detail. The same format was used for all interviews, creating standardisation and reliability. The key themes investigated were (1) the process of entry into the North American market and level of prior experience; (2) the strategic rationale for the acquisition; (3) cross-cultural issues; (4) the integration; (5) the acquisition outcomes. Throughout, emphasis was put on the factors identified as critical for success to establish their role and significance on the outcome of the transaction. Interviews were conducted by the first author at FirstGroup’s headquarters in Aberdeen, between January and March 2004. Interviews with each respondent typically lasted between one and two hours. All were face-to-face, except for the VP Maintenance based in the US where data was gathered via email. Notes were taken throughout the interviews, and a full record of each interview was written immediately after it took place to control interviewer bias. Several discussions were subsequently held with some of those respondents to verify the information and fill in gaps in the data. The finalised case study analysis was given to the managers of the company for corrections and adjustments. Other Sources of Evidence Documents and archival data were collected to augment and complement the interviews. Documentary evidence collected consisted of press releases, newspaper reports, corporate and miscellaneous websites, analyst research, promotional material, internal company presentations and market reports. Approxi- Interviewees’ Position and Roles in the North American Acquisition v FirstGroup Chief Executive (CEO). He has held this position since the Group’s formation in 1995, and has had a great deal of involvement in the North American acquisition, including negotiation of the deal. v FirstGroup former Business Change Director. Having been with the Group since 1986 before retiring in 2003, he was closely involved with the North American acquisition and subsequent operations. He held the position of Acting President of First America during this time, and spent eight months part time in the US. v FirstGroup Finance Director (FD). He was appointed to the Board in 2000, following the acquisition in North America. However, the integrated nature of the finance function has resulted in this Director working closely with the North American team, and making several international trips a year. v FirstGroup Chief Operating Officer UK (COO). He has had an overview of the international acquisition without being directly involved with running North American operations. He is now responsible for Yellow Bus (a US concept) within the UK. v Vice-President Maintenance of the School Bus Division of First America. A UK national currently placed in North America in a key engineering role, he has a great understanding of events and a unique expatriate perspective. 400 European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS mately 30 documents, totalling over 1000 pages, were analysed and around 20 websites were consulted. Data Reliability and Validity The use of retrospective accounts by executives for process research in strategic management enables to trace change over a long period of time when following change real-time is not possible. Furthermore, data is collected from those who are directly involved in shaping strategy processes and thus have greater strategic awareness (Hambrick, 1981, cited in Golden, 1992: 855). However, because it relies on individuals’ memories, retrospective data may be subject to errors (Golden, 1992). Various steps were taken to reduce the possibility of inaccuracies in respondents’ accounts. Firstly, the length of the integration period examined was five years, as this time span was long enough for at least some of the postacquisition changes to have been fully realised. At the same time, a five year-period was short enough for the company executives to be able to recall past facts with greater reliability. Secondly, in designing the interview questionnaires, care was taken to elicit past facts and behaviours rather than intentions and beliefs (Golden, 1992: 855). Thirdly, the use of multiple sources of evidence for each issue investigated enabled triangulation (Yin, 1994). A limitation of the study design however is that the respondents interviewed are all UK nationals. Data Analysis Results were analysed, by reconstituting the data in chronological order, in order to construct a process account of the events and issues in the acquisition process. The factors, which have been identified from the existing literature, were then used as categories to examine the data. This data was then compared and contrasted to literature already published. Case Study Background FirstGroup is the product of a series of domestic acquisitions, which took place in response to the deregulation of the industry in 1986. Up to this juncture, bus companies were regional, and owned and operated by the local authorities. Grampian Regional Transport (GRT) based in Aberdeen, was one such company and following deregulation, a successful management/employee buy-out was conducted. In 1995 GRT merged with a South-West England operator, Badgerline, to form FirstBus, and was subsequently floated on the London Stock Exchange. FirstBus aggressively acquired small and mediumsized UK bus operations. In 1997 and 1998, three privatised train companies and a 51% stake in Bristol International Airport were added to the portfolio, diversifying the company’s interests. 1 FirstBus took its preliminary international step through a joint venture in Hong Kong, operating transit buses on the mainland. To reflect the newfound diversity of the organisation, the name was changed to FirstGroup. In 1999 FirstGroup had disposed of its interest in Bristol Airport, and the Hong Kong joint venture to concentrate on the UK Bus and Rail market. As the UK market became mature, it offered limited opportunities for growth, necessitating FirstGroup to look towards international expansion. After conducting worldwide market analysis, North America became the chosen focus. In the summer of 1999, FirstGroup acquired Bruce Transportation, a school bus operator based in New England, and Ryder Transportation, the bus division of a global logistics group. Bruce gave FirstGroup an initial toehold in the North American market, but this was a small company compared to the scale of Ryder Transportation. With Ryder, FirstGroup acquired 10,000 buses and three divisions – school bus; public transit contracting and management services; fleet maintenance services -, operating in over 30 states across the country (WestLB Panmure Analyst Research, 2001). The acquisition also gave FirstGroup critical mass in a very large market with huge potential. FirstGroup’s North American Acquisition The Role of Previous Acquisition Experience FirstGroup’s History and Nature As noted above, prior to their entry into North America, FirstGroup had gained no real international acquisition experience but did have a great deal of experience on the domestic front. The UK bus division consists of 26 bus companies (FirstGroup Company Information, 2004), all of which have been acquired. The group was very familiar with the fast pace of growth that comes through acquisition, and their successful past experience and the lessons learned, had given them confidence to take on the acquisition of Ryder. This acquisition was however, considerably larger, than any that had gone before. 1 Although the company had no experience of international acquisitions, they had previous overseas business experience from which they had gained valuable lessons. The joint venture in Hong Kong, had taught FirstGroup about issues of cross-border control, and reinforced the belief that a wholly owned subsidiary was the right mode of entry for North America. The FD stated: Hong-Kong taught us that we could do an international acquisition, and that we didn’t like the joint-venture. That made the US a wholly-owned subsidiary decision. . . Jointventures have an accounting benefit, but the downside is that it takes a lot of management time. . . Joint-ventures have to go through boards and boards of people. This combination of a great number of domestic acquisitions, and the one international joint venture provided FirstGroup with experience in implementing change quickly. This experience would have European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 401 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS resulted in the firm being ‘more flexible, with developed adaptation skills’ (Hitt et al., 1998: 100), which have influenced the success of the US acquisition. FirstGroup has been described by their CEO as ‘a highly opportunistic organisation’. Continually assessing new options becoming available to them, FirstGroup concentrate their focus on areas of change within the industry, for instance the privatisation of the school bus industry in North America. The Group’s previous acquisition experience has therefore helped them develop the skills to quickly identify opportunities and take full advantage of them. One further unique element in FirstGroup’s advantage in making large acquisitions, was its past experience of itself being the product of a merger. In 1995 FirstGroup was formed through the merger of GRT with Badgerline. Badgerline was two to three times larger, but less profitable and well organised than GRT. The Former Business Change director, then a GRT executive, described the experience of the frustrations of being shackled by a merger with a larger, less nimble and less well organised group. Although this was a painful process, the GRT executives eventually dominated the organisation and as a result learned many valuable lessons. In particular it gave them a clear understanding of the de-motivational effects that a merger with a larger partner can have on the staff of the subordinate organisation. This was a vital learning process for FirstGroup executives, and was perhaps the critical factor in making them more aware of the need to ensure that the North American staff were on-side, motivated, empowered and felt that they were important to the development of FirstGroup as a whole. FirstGroup’s Inspection and Negotiation Approach to the US Target Through their domestic acquisitions FirstGroup have honed many skills that have aided them in their international acquisition process. In particular information gathering, negotiation and pre-acquisition planning have been very successfully developed. Because of the rapid, end on, nature of FirstGroup’s UK Bus company acquisitions in the 1990s, the Group had a very highly developed process of inspection. Whilst there was latterly a dedicated acquisition team, the function heads (Operations Director, Engineering Director, Commercial Director), as well as doing their day jobs, led the due diligence inspections into their specific function within the target companies. As a result, they had a very pronounced sense of ownership because they had to subsequently live with any shortcomings in this due diligence process when FirstGroup took over operational management. After initially using market research to evaluate the industry and select appropriate targets, the CEO 402 explains that he approached several organisations. After a visit to North America, he focused in on Ryder Transportation because of the close fit with his own Group. He explains: Ryder was 90% Trucking and Leasing and 10% Bus. I contacted the CEO of Ryder and offered to merge FirstGroup with their bus division, so as to get him interested. . . At this stage, Ryder was not for sale... (however) Ryder Business Development manager realised that it made sense to sell their bus division. . . After this initial sign of interest from the target, the CEO quickly moved on to the negotiation stage. The CEO and FD of the Group took charge of the negotiation, and over months of discussion, maintaining continuous contact with Ryder, managed to convince the target that their bus division was not one of their core sectors, and to achieve a good price for the acquisition from FirstGroup’s point of view. This point was confirmed by the warm reception received in the City for the rights issue to fund the acquisition. Clearly, the management team’s in-depth experience in negotiating previous acquisitions played a key role in obtaining best value for this transaction. Pre-acquisition Planning Due to FirstGroup’s extensive acquisition experience, the company’s pre-acquisition planning is highly practised, and can therefore be completed quickly. It has been described, by the former Business Change Director as being such a routine procedure as to be almost ‘formulaic’. With regards to the North American acquisition, the dedicated project team were responsible for pre-acquisition planning and a critical element of this – due diligence. As Ryder’s business was composed mainly of individual school contracts, it was relatively easy to investigate and there was high visibility of turnover and profit. Financial modelling was routinely executed, examining performance and sensitivities. As part of the due diligence inspections which function heads conducted in their respective function, FirstGroup were able to assess the competence of staff they would inherit and already be working on replacements for weak executives, usually by promoting others within the target. They also examined and planned the requirement for replacement systems and procedures where they were identified as inadequate. In conclusion, extensive acquisition experience has been a key factor in the success of FirstGroup’s US acquisition. Inspection, negotiation and due diligence skills are competences that have all been honed over a ten year period, and this has ensured selection of the correct acquisition target which is fundamental for long term success. In contrast with studies which highlight such system as essential for future success (Haspeslagh and European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS Jemison, 1991: (88–89)), FirstGroup have no formal mechanism for post-acquisition review. Instead FirstGroup’s continued success can be explained by their relatively stable board of directors and their ability to learn from past experience through informal mechanisms, which helped prevent them from making the same mistake twice. Indeed, according to the Former Business Change Director, it was not uncommon during new acquisitions for issues from previous ones to be referred to, so a learning process was taking place. Strategic Fit Evolution of FirstGroup’s Global Strategy Prior to the North American acquisition, FirstGroup had largely adopted an emergent strategy. This unstructured approach allowed the young Group to explore many options. The ‘take what comes along attitude’, 2 resulted in holdings as diverse as a 27 per cent share in a joint venture in Hong Kong, and a 51 per cent stake in Bristol airport. Both of these holdings have since been divested, as FirstGroup failed to gain critical mass in these markets. Subsequently, as a result of the restricted growth on the domestic front, FirstGroup’s approach to internationalisation became strategic. The company commissioned consultants reviews of all worldwide potential markets, and made a conscious decision to become a global player in its core business. It was following these developments that the Bruce and Ryder acquisitions took place. Entry to the North American market is one of the most important strategic decisions that FirstGroup have made (Child et al., 2001: 9). These acquisitions in a new geographic region (Hubbard, 2001) changed the shape of the Group and made it a truly multinational organisation. These acquisitions brought the Group immediate critical mass and elevated it to the number two position within the school bus industry. Assessment of the Target for Strategic Fit FirstGroup’s FD explained the three principal criteria used to assess Ryder as a suitable acquisition target: v Management Structure. ‘Does the structure of the company allow FirstGroup to have control over it?’ v Finance. ‘Can we finance this acquisition, in both the short and long-term?’ v Strategic Fit. ‘Does this company fit with our global strategy?’ FirstGroup’s Selection of a Favourable Set of Market Characteristics Critically, FirstGroup appear, as part of their overall strategy to have set out to replicate the unique set of circumstances which the UK provided them in the 1990s. At the time there was a major movement away from public ownership to private, with significant opportunities for cost savings and efficiencies. However, in North America FirstGroup had the opportunity of a growing overall market, whereas in the 1990s the total market in the UK was still shrinking. Timing and in particular first mover advantage, were also very critical to this strategy and no doubt FirstGroup saw the appointment of a Republican President, as a further positive omen for the movement towards outsourcing and privatisation. Whether by accident or design, FirstGroup have chosen a strategy of not merely reproducing their core business abroad, but of seeking out a political/economic set of circumstances which almost replicates that on which their previous success was founded. In conclusion, strategic fit was the single most important factor for FirstGroup’s successful acquisition. Selection of an acquisition target with a supportive set of market features, with a strong and sound management structure, which most importantly mirrored closely its core business, contributed greatly to the difference between success and failure. This focus on core business is an element of strategic fit that will now be explored. Focus on Core Business A key part of our global strategy is to stick with what we know. The words of FirstGroup’s CEO summarise the company’s emphasis on maintaining a focus on their core business. The acquisition of Ryder allowed FirstGroup to maintain its strengths and exploit its competitive advantage in a new geographical market (Hitt et al., 1998: 101–102). FirstGroup had no direct experience of operating in the US Transit, or School Bus markets, but the similarities to their core UK operations, presented FirstGroup with the opportunity to export their core competences. However, the Services division which FirstGroup inherited from the acquisition, moved outside the boundaries of the core business, although it remained related as it drew on one of FirstGroup core skills – vehicle maintenance. As this accounted for less than 10 per cent of the acquisition it was not perceived as a problem, and is currently a thriving and growing business. The FD explained: It is easy to say ‘this is not core, let’s get rid of it.’ But if it looks good, we have to ask the question, ‘can we make it work?’ If it doesn’t work out, and you decide that it’s not where you want to be, at least you are selling a going concern. FirstGroup’s North American acquisition was successful, partly due to the fact they bought a company they knew how to run. With an international acquisition, focussing on a core business, where it is clear European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 403 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS how to exploit your competitive advantage, provides an organisation with more time to dedicate to overcoming the ‘international’ problems such as culture and distance from the home country. sidiary of a much larger group, and fitted into this role relatively smoothly. This was perhaps aided by the fact that there was not a huge amount of corporate change for employees at the bottom of the hierarchy, post acquisition. Cultural Fit The combined culture of the two entities has evolved over time, and with greater exposure to each other, they have become more aligned. The FD reflected that: National Culture First America has operations in Canada and in over 35 states in the US, from Alaska to Florida (FirstGroup, 2003). Due to the sheer size of the continent, the culture varies from location to location. The VP Maintenance of the school bus division of First America, explained the diversity of the country cultures and business approach: from the ‘laid back’ approach of the West, and the ‘conservative’ mid-West; to the more ‘aggressive’ and at times, ‘European’ style of the East coast. Being so widely represented across the North American continent greatly amplified the potential culture related problems which might have resulted from such a cross-border acquisition. Several Directors interviewed, commented that there was a general misconception that the UK and US have similar cultures and values. In practice, they found the situation to be very different. One of the biggest disparities between the UK and North America that was expressed, was the presence of the ‘good news’ phenomenon, particularly in the US. The COO explained that US employees were more than eager to broadcast good news, but tended to hold back bad news. Another difference highlighted by the former Business Change Director, was that the Americans had a very ‘sales and customer orientated approach’, whereas the Brits were much more ‘bottom line’ driven. ‘Two countries divided by a common language’ George Bernard Shaw’s quote about the UK and US, highlights another problem initially faced by FirstGroup. Although the two countries speak the same language, the different uses and connotations of certain words was an initial problem. The COO illustrated this point, using the example of pensions. Discussing a pension ‘scheme’, was seen to the Americans as talking about a pension fiddle or scam, rather than a pension plan! The problems identified above, have largely been overcome through an awareness of the situation and anticipation of any differences that may arise. North American operations are run by host-country nationals, who are more aware of their own country’s cultural variations, and this cultural awareness is imperative when dealing with customers from geographically diverse areas. Organisational Culture The organisational cultures of Ryder and FirstGroup are complementary. Ryder was used to being a sub404 We’re now five years on and the organisational culture has got better in the latter stages. The Business Change Director ensured that the US worked closely with the UK. There was a three to six months time period where the FD and the Business Change Director were both in the US. It will have really shown the Ryder team that FirstGroup were together on all matters, and this was an important message. . . The UK and the US have a good working relationship, but it is clear that the UK calls the shots. The CEO highlighted the key issue of trust within the organisation. He stated that it was imperative for success, that the UK and US trust their colleagues on the other side of the Atlantic, but that it is only after a considerable change-out of Senior Executives, that the required level of trust has been achieved: The trust is now very strong and the US feels part of the FirstGroup team. In terms of organisational culture, FirstGroup places less emphasis on ‘soft issues’ such as human resource management and marketing than the US subsidiary. These are skills which Ryder consider important, and at which they are highly competent, partly because of the necessity for good relationships with schools, pupils and parents alike. This contrast not only provides the possibility of conflict, but an opportunity for learning if handled in the correct way. FirstGroup have left those matters in the hands of US nationals and even looked to adopt some of the North American practices, demonstrating their recognition and acceptance of the US subsidiary’s expertise. There is no doubt that FirstGroup’s 1995 merger helped their executives to understand the concerns of a large company being taken over, and this would have led to a more sympathetic, listening approach to Ryder. Whilst it is important that national and organisational cultural differences are recognised and taken on board in international acquisitions, the low level of integration in this particular case has meant that it is less of an issue for success. Nevertheless FirstGroup appear to have resolved the principal cultural issues which could have led to problems. Integration Level of Integration On the matter of integration, the CEO of FirstGroup explains: European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS First America is a stand alone company. . . You integrate to achieve synergies, and at this stage that’s just not possible. Due to the nature of the industry, and the distinct businesses on either side of the Atlantic, there are only a few possibilities for economies of scale or scope. 3 The low level of integration selected for First America has resulted in all main functions being retained by the subsidiary. Operations personnel in the UK and North America have little contact, as their functions are so distinct, with North America having a strong contracting focus. However, the audit, insurance and finance functions all work closely with their overseas partners, as these are areas where the few synergies available, do exist. FirstGroup have opted for restructuring of its acquired subsidiary, followed by the implementation of financial controls. This is the second least level of integration as identified by Hubbard (2001: 57) and consists of modifying the target company ‘to some extent’, then leaving it ‘to operate in a stand-alone capacity with little interaction with other business units. Financial controls are implemented to ensure that the business unit complies with head office strategies and objectives’. Child et al. (2001: 95) have identified that it is imperative that integration takes place at an appropriate level. There are several implications that stem from this fundamental decision of the ‘appropriate level’ of integration. Fuller integration often results in a loss of power on the part of the target, and as a consequence senior target employees are more likely to leave voluntarily. Further, where a higher degree of autonomy is given to the target company it results in a lower level of complexity in the implementation process, as integration affects a lower number of employees and business units. Finance: A Key to Integration Finance has played a fundamental role in the integration. Upon acquisition of Ryder, FirstGroup found the company to be less commercially aware and profit driven than the UK. The former Business Change Director explains that budgets were written, but deviation from these did not appear to be a problem to North American management. This was partly due to the fact that public sector values still dominate in the North American bus industry, as it is only starting to move into the private sector. This situation led FirstGroup to reinforce financial controls in the US subsidiary. The first CEO appointed to First America was FirstGroup’s FD. He brought with him a British Chief Financial Officer for North America and together they overhauled the financial function and put in place the UK finance system. FirstGroup introduced key performance indicators and a much greater emphasis on performance delivery throughout the organisation. The former Business Change Director explains: Deviation meetings were implemented once a month, where the Regional Vice-Presidents flew in to meet with the CEO. Contract by contract they compared performance to budget and agreed on corrective actions where necessary, as well as discussing issues that they were facing in their region. The Regional VPs found this level of accountability very difficult, and as a result many were replaced. FirstGroup’s quick implementation of total financial integration mirrors literary thinking. Studies have found that ‘the dominant influence of the City has encouraged a short-term financial emphasis’ for UK management (Child et al., 2001: 58), and many British firms rely on financial performance to control their subsidiary (Morgan et al., 2001: 49–50). Controls Over the Acquired Company In addition to installing their financial controls, FirstGroup have also appointed a small number of homenation staff to key positions. The first CEO following the acquisition was British, as was his replacement. The first Chief Financial Officer was also British, he implemented all the new financial controls, and has more recently been succeeded by the previous Group Internal Auditor from the UK. There has therefore been a strong UK presence at the top of the finance function, and from time to time, various other UK personnel came to assist in implementation of the finance systems. In the First Student Division, the VP Maintenance was appointed from the UK. At an early stage inadequacies in the maintenance system were recognised, and staff were changed out. He also brought with him an assistant from the UK and together they overhauled the company’s entire maintenance function. This has been the extent of the import of UK Executives onto the North American team, but their contribution has been very significant. By doing this FirstGroup has not only achieved a higher level of control in key functions, but as a byproduct has gained greater integration over time. These individuals have an increased knowledge of the UK’s processes and procedures and are generally more willing to embrace them. This highlights the overlap between integration and control (Child et al., 2001: 97). Despite the control mechanisms mentioned above, the subsidiary operates almost as a stand-alone entity, with reporting occurring to the Group via the First America CEO. In addition, the group today relies on a mix of home- and host-national control. The FD states: . . .FirstGroup need enough Brits in North America, but not too many. While the first two CEOs were British nationals, the decision was taken to appoint a US national because it was felt that both customers and staff would align themselves more readily with an American. This evolution in FirstGroup’s staffing approach is another example of their openness. European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 405 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS To sum up, FirstGroup’s integration approach is characterised by a low level of integration with stringent financial controls. While it is clear that the UK hold the purse strings 3, this approach has enabled the group to take advantage of the industry and cultural expertise that the US nationals hold. A delicate touch has been employed with the injection of UK nationals to key functional positions, and over time the Group has realised that North American operations should be run by host-country nationals, who are more aware of their own country’s cultural variations. Acquisition Performance Operating Performance In financial terms, FirstGroup views the North American acquisition as having been successful. As indicated in Table 2, turnover has increased from £462.7 mn in 2001 to £665.8 mn in 2005, an increase of 44%. Operating profit for the North American division has increased by 8.8% between 2001 (£56.3 mn) and 2005 (£61.2 mn). According to the 2004 company report, since the acquisition in 1999, turnover has grown by 73% and profit by 65%, generating a cash return on invested capital of 12%. FirstGroup reports earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization of £108.1 mn in 2005 (2004: £107.1 m; 2003: £103.3 m), and reports that its North American division is self-financing for maintenance capital expenditure and growth organically and via acquisitions. Synergy Realisation Various sources of synergy have been identified, which have contributed to a sound financial performance and enhanced FirstGroup’s long-term competitiveness. Firstly, as explained in the section on Strategic Fit, by acquiring the second largest player in the US school bus industry and positioning itself in a market with significant growth potential, FirstGroup has enhanced its market power, which in turn enables it to compete more effectively in the increasingly global public transport industry. Table 2 The following example explained by the former Business Change Director illustrates how the North American acquisition benefits from being part of a large group. In the US, bus specifications are invariably state specific. In the past this gave only two options upon loss of a contract. Either the vehicle had to be sold, or transferred to another contract in that State, neither being very efficient. FirstGroup has worked with its suppliers to produce an ‘InterState Bus’. The core of the vehicle is fitted with sockets capable of taking numerous additional optional fittings e.g. extra lights, flashers, horns, signs etc. so that these can be added or removed as appropriate. This creates a much more versatile transferable vehicle. Clearly, it has taken a global player with muscle with its suppliers to provide this economic solution. Second, by transferring its core competences in the finance and maintenance functions, which it developed as a result of its early experience of privatisation and deregulation in its domestic market, FirstGroup has improved the management of the US business. This expertise has been extremely beneficial to the acquired firm, as the US market is now evolving along a similar path as the UK. Third, synergies have resulted from the reverse transfer of knowledge from the North American operation to the UK market, an unexpected benefit for the group. FirstGroup has imported the US concept of the Yellow School bus, which was inexistent in the UK. In the US, the yellow school buses transport 23 million students to and from school every day (UBS Warburg, 2002), the whole system being based on a philosophy of ensuring the safety of the school pupils. The scheme was launched in the UK in 2002 and currently FirstGroup has 20 Yellow Buses in the UK operating on trial in several sites around the country. According to the COO, the introduction of the scheme has been positively received by communities and the government alike, as it coincides with growing concerns over safety, road congestion and pollution. Thus, this reverse transfer of know-how has resulted in the creation of new business opportunities for FirstGroup and enhanced its core business. Global learning has also successfully Financial Performance of FirstGroup’s North American Divisiona 2000b 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Turnover (£m) (% increase over previous year) 246.4 462.7 – 542.9 (+17.3%) 582.4 (+7.3%) 620.7 (+6.6%) 665.8 (+7.3%) Operating profit (£m) (% increase over previous year) 34.5 56.3 – 60.8 (+8%) 61.3 (+0.8%) 63.5 (+3.6%) 61.2 ( 3.6%) Operating margin (%) EBITDA (£m) 14.0 – 12.2 – 11.2 – 10.5 103.3 10.2 107.1 9.2 108.1 a b Sources: FirstGroup Company Reports 2000 to 2005. For 2000, results are only available for 6 1/2 months (September 1999 to March 2000). All other years are full financial year results. 406 European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS taken place in aspects of the HRM and safety functions, where, as explained above, FirstGroup have found that its US operation is relatively more advanced due to the specificities of its national and industrial environment. This has in turn provided FirstGroup with a competitive advantage over its competitors. Discussion The case study of FirstGroup’s North American acquisition supports the framework developed in this paper. The role of each variable as well as the interrelationships between all the variables and acquisition success is confirmed. Findings show that previous acquisition experience is significantly and positively associated with international acquisition success, through ensuring the presence of all the other success factors: strategic fit, focus on core business, cultural fit and integration. As a serial domestic acquirer, FirstGroup had honed many of its in-house skills, through its experience. The highly opportunistic nature of this organisation resulted in it experimenting with international joint ventures, non-core businesses and playing the role of the subordinate organisation in a sizeable merger. These events have resulted in FirstGroup learning key lessons early, fortunately, without fatal consequences. Both of these experiences have provided the UK group with essential skills, which have in turn ensured the selection of the correct acquisition target as well as facilitated the integration process. The study contributes to our understanding of the role of prior acquisition experience in an international context, and illustrates the mechanisms through which firms can learn from past experience in such a way as to enhance the performance of their subsequent acquisitions. In the case study, a key learning mechanism has been the group’s relatively stable board of directors and their ability to learn from past experience through informal mechanisms. This contrasts with the literature which highlights formal mechanisms for post-acquisition review as essential for future success (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991: 88–89). A second factor which explains that extensive learning has taken place is linked to the absorptive capacity of the group, which has in turn been shaped by its early experiences. Throughout its existence FirstGroup has shown an open attitude and a willingness to learn, which can partly be linked to the group’s emergence from a troublesome merger in its early years, as well as it’s young age. Findings also confirm that strategic fit and focus on core business are critical antecedents to cross-border acquisition success. FirstGroup’s strategy led them to find a unique favourable market position, with characteristics very similar to those which brought about their major growth in the UK during the privatisation process. Gaining first mover advantage in this market was also vital. Furthermore FirstGroup has maintained a focus on core business. Focus on core business positively affects success firstly by maximising the potential for value-creating synergies, due to the similarity of both firms’ industrial environments. Secondly, as the acquiring firm is knowledgeable about the industry, it can dedicate more time to overcome the other ‘international problems’ such as cultural differences. Nevertheless, an element of diversification can be beneficial by creating real options and new growth opportunities (e.g. Karim and Mitchell, 2000, Cited in Sudarsanam, 2003: 116), provided that it remains within the boundaries of the acquiring firm’s core competences. FirstGroup has gained a valuable related diversification in the domain of vehicle maintenance, which has helped the group realise the potentialities of this market. Thus, findings contribute to the limited research on the role of relatedness on cross-border acquisition performance. The case study confirms that integration is a critical success factor (e.g. Child et al., 2001; Haspelagh and Jemison 1991). However, our findings about the links between the level of integration and the realisation of synergies contradict existing theory on integration. Whilst recognising that different modes of integration will be adopted depending on the nature of the strategic interdependencies between acquired and acquiring firms, Haspelagh and Jemison (1991) argue that a company must integrate to create value from an acquisition. Similarly, Larsson and Finkelstein (1999: 16) find that a higher degree of synergy realisation is associated with higher levels of integration: ‘. . .structural and processual changes must be undertaken that allow (potential) synergies to be realised’. Low integration is typically associated with conglomerates, where mainly financial synergies are sought. However, the case study shows that significant and not merely financial, value-creating synergies can be achieved without the need for integration. Because of the nature of the public transport industry which requires local knowledge and the diversity of the US culture, FirstGroup opted for low integration coupled with stringent financial controls. Low integration has enabled FirstGroup to improve the management of the US business where necessary, while overcoming the problems arising from the many cultural differences, which exist between North America and the UK. In this transaction, value has been created through enhanced market power and revenues, thanks to the selection of a fundamentally sound business operating in a high growth market, and a better management of the US business. Another synergy that has been realised European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 407 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS without integrating the US business, has been the reverse transfer of best practices from the target to the UK, which has enhanced FirstGroup’s domestic core businesses. Therefore, an acquisition at the right price, at the right time, in the right market conditions, followed up by better management of the business, can create value in itself. This leaves further integration as an option for the future, to create further value. This finding makes sense in light of a study by Seth et al. (2002: 938), which suggests that some sources of value creation in cross-border acquisitions differ from those in domestic acquisitions, due to the diversity of motives that may underlie international acquisitions. It is therefore logical to expect that the links between modes of integration and the extent of synergy realisation need to be re-evaluated in an international context. The global nature of an industry will be a fundamental determinant of the potential types of synergies that exist in an international acquisition. A long line of studies have concluded that cultural fit is a critical determinant of acquisition success. However, few studies have considered its role in conjunction with other antecedents. First, the case study shows that problems which might arise from cultural differences can be solved through an awareness and anticipation of cultural differences. Second, findings point to a strong interdependence between cultural fit and integration. In the case study, cultural fit has not had a major impact on the North American acquisition, due to the low level of integration adopted. The importance of cultural fit on acquisition success will partly depend on the level of integration chosen. Conclusions The case study of FirstGroup’s successful market entry into North America supports a process and integrative framework for understanding the performance of cross-border acquisitions. Whilst only based on one case study, this exploratory study contributes to the limited research on the determinants of international acquisition success. Cross-border acquisition success is found to be function of the acquiring firm’s prior acquisition experience, strategic fit combined with a focus on core business, cultural fit and the integration process. Whilst factors such as national cultural fit uniquely affect cross-border acquisitions, other factors which have been found to affect acquisition performance in a domestic context, are also found to play an important role in an international context. The study also contributes by showing the relationships between all the variables and acquisition success, and in so doing has offered important insights. While there is a great deal of literature supporting the notion that North America is a graveyard for 408 UK companies, the case study shows that in the presence of the appropriate success factors, it is possible to succeed in this market. There is no doubt that certain sectors are particularly competitive, such as retail, telecoms and technology. However, there are sectors, particularly in the service industry, where UK companies are quite far advanced along the path of evolution. In the sector chosen for this study, the comparatively early promotion of privatisation in the UK has allowed companies to acquire expertise well ahead of other geographical regions. This identification of a market sector, in which the UK has a competitive advantage, combined with a respect for the diversity of culture in North America, can be very successful and leave plenty of scope for sustainable growth. Many practical implications can be drawn from the case study for companies conducting cross-border acquisitions: v This study has implications for the way in which companies conduct their global strategy. It is one thing to see a market opportunity, such as an opening for a core product. However, FirstGroup found a uniquely similar, favourable market climate, to that which had proved so successful domestically. This unique set of market circumstances has been a critical factor for the success of FirstGroup. When combined with a fast growing market it becomes a very compelling strategy. v Lessons can be learned from the integration approach adopted by FirstGroup. Under certain industry and cultural conditions, low integration can be very beneficial. Various sources of synergy can be capitalised upon. Partial integration can also help avoid cultural problems and have a motivational effect on the target staff. v Companies need to remain open to learning opportunities. Not ignoring opportunities for reverse transfer of knowledge, is another important lesson, as on some occasions, best practice will originate from a subsidiary. Two-way transfer of knowledge can also have a positive motivational, and early acceptance effect on the target staff. One of the clear limitations regarding this research, is the fact that the case study is merely based on one company, within one sector of the service industry. However, although findings of this research cannot necessarily be generalised across all business sectors, it may be highly appropriate to further apply the findings of this case study to similar sectors of the service industry as the basis of further research. It would also be interesting to examine the impact of these selected factors, on the success and failure of other service industry acquisitions in North America. A final appealing future research question would be to examine FirstGroup’s North American experience, European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS as it plays out over time, to determine whether their success is sustained, and the benefits from the acquisition continue to accrue. Acknowledgement We thank Paula Jarzabkowski (Aston U.) and three anonymous reviewers from the 2006 annual Academy of Management meeting for helpful comments on this paper. This paper was presented at this meeting in August 2006, Atlanta. We also thank the editorial team of this journal. Notes 1. Interview with former Business Change Director. 2. Interview with COO. 3. Interview with FD. References Barkema, H.J., Bell, J.H.J. and Pennings, J.M. (1996) Foreign entry, cultural barriers and learning. Strategic Management Journal 17, 151–166. Calori, R., Lubatkin, M. and Very, P. (1994) Control mechanisms in cross-border acquisitions: An international comparison. Organization Studies 15(3), 361– 380. Chandler, A.D. (1986) The evolution of modern global competition. In Competition in Global Industries ed. M.E. Porter, pp. 405–448. Harvard Business Press, Boston. Child, J., Faulkner, D. and Pitkethly, R. (2001) The Management of International Acquisitions. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Clemente, M.N. and Greenspan, D.S. (1998) Winning at Mergers and Acquisitions. John Wiley & Sons, New York. Datta, D. and Puia, G. (1995) Cross-border acquisitions: An examination of the influence of relatedness and cultural fit on shareholder value creation in U.S. acquiring firms. Management International Review 35, 337–359. De Wit, B. and Meyer, R. (2004) Strategy: Process, Content, Context. (3rd ed.). Thomson, London. Finkelstein, S. and Haleblian, J. (2002) Understanding acquisition performance: The role of transfer effects. Organization Science 13, 36–47. FirstGroup (2003) Annual Report. FirstGroup Company Information [cited 28th January 2004] http://www.firstgroup.com/corpfirst/company/company profile.php. Golden, B.R. (1992) The past is the past – or is it? The use of retrospective accounts as indicators of past strategy. Academy of Management Journal 35(4), 848–860. Haleblian, J. and Finkelstein, S. (1999) The influence of organizational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: a behavioural learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly 44, 29–56. Haspeslagh, P.C. and Jemison, D.B. (1991) Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value Through Corporate Renewal. Free Press, New York. Hayward, M.L.A. (2002) When do firms learn from their acquisition experience: Evidence from 1990-1995. Strategic Management Journal 23, 21–39. Hitt, M., Harrison, J., Ireland, D.R. and Best, A. (1998) Attributes of successful and unsuccessful acquisitions. British Journal of Management 9(2), 91–115. Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage, Beverly Hill. Hopkins, H.D. (2002) Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Global and regional perspectives. In International Mergers and Acquisitions, (eds) P.J. Buckley and P.N. Ghauri, pp. 86–116. Thomson, London. Hubbard, N. (2001) Acquisition Strategy and Implementation. (2nd ed.). Palgrave, Basingstoke. Larsson, R. and Finkelstein, S. (1999) Integrating strategic, organizational and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: A case survey of synergy realization. Organization Science 10(1), 1–26. Lawrence, P. (1996) Through a glass darkly: Towards a characterization of British management. In The Professional Managerial Class: Contemporary British Management in the Pursuer Mode, (eds) I. Glover and M. Hughes, pp. 37–48. Aldershot, Avebury. Morgan, G., Kristensen, P.H. and Whitley, R. (2001) The Multinational Firm: Organizing Across Institutional Divides. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Seth, A., Song, K.P. and Pettit, R.R. (2002) Value creation and destruction in cross-border acquisitions: An empirical analysis of foreign acquisitions of U.S. firms. Strategic Management Journal 23, 921–940. Shimizu, K., Hitt, M.A., Vaidyanath, D. and Pisano, V. (2004) Theoretical foundations of cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A review of current research and recommendations for the future. Journal of International Management 10(3), 307–353. Shrivastava, P. (1986) Postmerger integration. Journal of Business Strategy 7(1), 65–76. Sudarsanam, S. (2003) Creating Value from Mergers and Acquisitions: The Challenges. Prentice Hall, Harlow. UBS Warburg (2002) Bus and Rail Review. London. Very, P. and Schweiger, D.M. (2001) The acquisition process as a learning process: Evidence from a study of critical problems and solutions in domestic and cross-border deals. Journal of World Business 36(1), 11–31. Weber, Y., Shenkar, O. and Raveh, A. (1996) National and corporate fit in M& A: An exploratory study. Management Science 4, 1215–1227. WestLB Panmure (December 2001) US School Buses. London. Yin, R.K. (1994) Case Study Research: Design and Methods. (2nd ed.). Sage, Beverly Hills. European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006 409 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL ACQUISITION SUCCESS CATRIONA DUNCAN, Marks & Spencer, London, UK. Catriona Duncan has an MA(Hons) in International Business from the University of Edinburgh. She currently works for Marks and Spencer in Central London. 410 MONIA MTAR, School of Management, Strategy and International Business Group, University of Edinburgh, 50 George Street, Edinburgh EH8 9JY, Scotland, UK. Monia Mtar is a Lecturer in Strategic Management at the University of Edinburgh. She holds a Ph.D., from the University of Warwick. Her research interests are cross-border mergers and acquisitions, strategic and organisational aspects of multinational management; French multinationals; international institutional theory. European Management Journal Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 396–410, December 2006