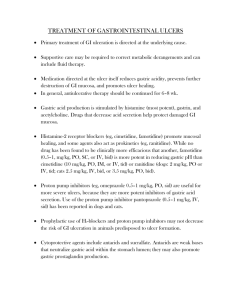

Peptic Ulcer Disease 002.5-7125/91 $0.00 + .20 Surgical Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease Ajit K. Sachdeva, MD, FRCS(C), FACS,* Howard A. Zaren, MD, FACS,t and Bernard Sige/, MD, FACS:!: Surgery for peptic ulcer disease has gone through a period of significant change over the past 15 years. The declining incidence of the disease, the introduction of H 2 -receptor antagonists (as well as other effective drugs to control acid secretion), the development of proximal gastric vagotomy, and re-evaluation of older procedures have all contributed to the emergence of a new era in the surgical management of peptic ulcer disease. The incidence of peptic ulcer disease was on the decline even prior to the introduction of H 2 -antagonists in 1977, and the decline in the number of patients hospitalized for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease has continued since that time. However, hospitalization rates for hemorrhage and perforation have remained constant. 33 In some series, hospital admissions for hemorrhage have even shown an increase. 1 Operations for peptic ulcer disease have followed these general trends. Emergency procedures for hemorrhage have increased and account for from 20% to 50% of all surgical procedures performed for peptic ulcer disease. 22,38, 34 . The use of proximal gastric vagotomy without a drainage procedure for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease was first reported between 1969 and 1970. Since that time, this "physiologic" procedure increased in popularity and then because of the significant ulcer recurrence rate enthusiasm diminished. However, the p;'ocedure is still a viable option in several clinical situations because of its low complication rate. Several age and gender differences in patients with peptic ulcer disease are worthy of note. In recent years, patients requiring surgery for peptic *Associate Professor of Surgery, and Director of Surgical Education, Medical College of Pennsylvania; and Chief, Surgical Services, Veterans AfFairs :\ledical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsvlvania tProfessor ~f Surgery, and Interim Chairman, Medical College of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsvlvania :j:Professor '01' Surgery, and Director of Surgical Research, J\[edical College of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Medical Clinics of North America-Vol. 7.5, No. 4, July 1991 999 lOOO AJIT K. SACHDEVA ET AL. ulcer disease have been older and have associated medical problems. Although the majority of candidates for surgery are men, the proportion of women requiring such operations has increased. 22 The prevalence of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug usage in the adult population might account for the increase seen in hospitalizations for bleeding gastric ulcers. 33 The operative mortality following elective surgery is generally from 1% to 2% and depends on the type of procedure as well as the operative risk of the patient. Emergency operations are associated with an almost 10fold increase in operative mortality.22 This underscores the need for earlier identification of patients who might benefit from elective surgery for peptic ulcer disease. OPERATIONS FOR PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE The surgical procedure for peptic ulcer disease must be taiiored to the specific needs of the individual patient. Efficacy of the procedure must be balanced against the risk to the patient. For optimum results, the surgeon should be able to select the appropriate procedure from a variety of available options. Truncal Vagotomy and Drainage Vagotomy remains pivotal in the surgical treatment of duodenal ulcer disease. Vagotomy decreases acid production by diminishing the cholinergic stimulation of the parietal cells and by decreasing the response of parietal cells to gastrin. Reports indicate that basal acid production is reduced by 70% and stimulated acid production is reduced by 50% following truncal vagotomy.40 Due to total denervation of the stomach (along with other intraabdominal viscera), truncal vagotomy alone would result in poor gastric emptying and gastric stasis. Hence, this procedure must be combined with a drainage procedure, either pyloroplasty (Fig. 1) or gastrojejunostomy. Truncal vagotomy and drainage are relatively easy to perform and are associated with low operative mortality and with an ulcer recurrence rate of from 10% to 15% (Table 1). Mild symptoms of diarrhea and dumping are fairly common following this procedure, but they can be managed conser- Figure 1. Truncal vagotomy and Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. 1001 SURGICAL TREATMENT OF PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE Table 1. Results of Operations for Duodenal Ulcer Disease OPERATIVE ULCER PROCEDURE MORTALITY RECURRENCE Truncal vagotomy and drainage Truncal vagotomy and antrectomy Subtotal gastrectomy Proximal gastric vagotomy 1% 1-2% 1-2% <O.S% 1O-1S% <1% 3-S% 1O-1S% Data from references 12, 2S, 40, and SO. vatively in most cases. The incidence of severe diarrhea and dumping is relatively low (Table 2). Truncal Vagotomy and Antrectomy The addition of antrectomy to truncal vagotomy (Fig. 2) results in the most effective operation for duodenal ulcer disease. Using this surgical treatment, the basal acid production is reduced by 85% and stimulated acid production is reduced by 80%.40 Reconstruction may be performed by a gastroduodenostomy (Billroth I) or a gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II). Although truncal vagotomy-antrectomy is associated with a slightly higher mortality rate, in elective situations with good-risk patients, mortality rates have been quite low. The ulcer recurrence rate for the truncal vagotomyantrectomy procedure is very low (see Table 1), and the incidence of diarrhea and dumping is similar to truncal vagotomy and drainage procedures (Table 2). Subtotal Gastrectomy Subtotal gastrectomy without vagotomy involves excision of up to 75% of the distal stomach with a Billroth I or Billroth II anastomosis. This procedure results in the removal of the gastrin-producing antrum and part of the parietal cell mass. The operative mortality rates are generally in the same range as for truncal vagotomy-antrectomy. However, the ulcer recurrence rate after subtotal gastrectomy is higher than for truncal vagotomyantrectomy (see Table 1). Although the incidence of diarrhea after subtotal gastrectomy has been reported to be a little lower than for vagotomyantrectomy in some series, the incidence of postoperative dumping is similar for both procedures. 12 Table 2. Undesirable Consequences Following Operations for Duodenal Ulcer Disease DIARRHEA PROCEDURE Truncal vagotomy and drainage Truncal vagotomy and antrectomy Proximal gastric vagotomy DUMPING Mild Severe Mild Severe 20-2S% 1% 10-20% 1% (or higher) 20-2S% 1% 10-20% 1% (or higher) <S% 1% Data from references 23, 40, SO, and SS. 2% <1% o ~ ~ ~ Figure 2. Truncal vagotomy and antrectomy. SURGICAL TREATMENT OF PEPTIC ULCEH DISEASE 1003 Proximal Gastric Vagotomy Proximal gastric vagotomy involves division of the vagus nerve branches to the parietal cells, leaving the nerve supply to the antrum and pylorus intact. Hence, the nerves of Latarjet are preserved and the proximal stomach denervated, including the distal 6 cm of the esophagus. The nerves are divided up to a point approximately 5 to 6 cm proximal to the pylorus (Fig. 3).24 Acid production may be reduced 80% to 90% in the early postoperative period, but this usually diminishes to 70% to 80% and remains at that level for years. Stimulated acid production may be reduced as much as 80% soon after the operation. However, this reduction also drops to around 50% after 1 year. 44 Although proximal gastric vagotomy is technically more demanding and is difficult to perform in obese individuals, it has been associated with a very low operative mortality (see Table 1). The operation does not require a drainage procedure, and other undesirable consequences are fewer (Table 2). However, the high ulcer recurrence rate reported following this procedure has made the procedure less popular. Recurrence rates of up to 30% have been reported in the literature, but the usual recurrence rates are around 10% to 15% when surgical technique is meticulous and includes denervation of the distal esophageal region (Table 1). Higher recurrence rates have also been reported in some series when the procedure was performed for pyloric channel or prepyloric ulcers. Selective Gastric Vagotomy In an attempt to selectively denervate the entire stomach (including the antrum and pylorus) but preserve the hepatic and celiac branches of the vagus nerves, the procedure of selective gastric vagotomy was performed by several surgeons in the United States and in Europe. However, it does require a drainage procedure because the antrum and pylorus are denervated. A recurrence rate of 2% after 5 years has been reported, attesting to the efficacy of selective gastric vagotomy.29 A lower incidence of diarrhea compared with truncal vagotomy has been reported in a few series, but the incidence of dumping after selective gastric vagotomy is similar to that following truncal vagotomy and drainage. 12 Overall, the procedure does not have significant advantages over truncal vagotomy and drainage, and it is Figure 3. Proximal gastric vagotomy. 1004 AJIT K. SACHDEVA ET AL. technically more demanding. Hence, selective gastric vagotomy currently is not very popular. Other Complications Following Operations for Peptic Ulcer Disease In addition to diarrhea and dumping, another troublesome complication following surgery for peptic ulcer disease is alkaline reflux gastritis. Alkaline reflux gastritis may occur after gastric resections (with Billroth I or 11 reconstruction) or following pyloroplasty. However, it is seen very rarely following proximal gastric vagotomy. If the diagnosis of alkaline reflux gastritis is confirmed by endoscopy and biopsy in a patient who presents with epigastric pain and bilious vomiting, reoperation may be indicated in severe cases. In cases in which the original procedure was resection and Billroth I or 11 anastomosis, conversion to a Roux-en-Y anastomosis may be undertaken (Fig. 4). If the original procedure was vagotomy and drainage, resection with Roux-en-Y reconstruction should be performed. Vagotomy must be added, if not previously performed, to prevent subsequent ulceration with a Roux-en-Y procedure. Results are generally favorable following Roux-en-Y conversion, although failure rates as high as 30% to 50% have been reported. 41 Also, Roux-en-Y conversion may result in delayed gastric emptying; Several authors have reported increased incidence of carcinoma in the gastric remnant 15 to 25 years after partial gastrectomy for benign peptic ulcer disease. In one series, risk appeared to be 3.2 times higher after 25 years, as compared with the general population. 52 Hence, careful endoscopic surveillance of such patients is indicated 12 to 15 years following gastrectomy. Other complications of gastric surgery include afferent loop syndrome, bezoar formation, and malnutrition. Figure 4. Roux-en-Y reconstruction after partial or subtotal gastrectomy. SURGICAL TREATMENT OF PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE 1005 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY AND CHOICE OF OPERATION FOR PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE Hemorrhage The overall mortality for hemorrhage from peptic ulcer disease remains around 10% to 20%. Although 75% of patients admitted with massive hemorrhage from peptic ulcer disease will stop bleeding spontaneously within 48 hours, some patients with life-threatening hemorrhage will require emergency surgery. Mortality rates are higher for patients who are older than 60 years, for patients who require more than five units of blood transfusion, and for patients who have multiple system failure. 35 Hunt20 reported that shock on admission to the hospital was associated with a significantly greater incidence of re-bleeding in 70% of cases. Also, patients with endoscopic stigmata of recent hemorrhage and those with hemoglobin levels of less than 8 g/dL at admission appear to be more likely to have further bleeding. 7 A visible vessel on endoscopy has been reported to be associated with up to a 60% chance of further bleeding. 27 Chronic ulcers that are bleeding from an artery at the time of endoscopy continue to bleed or re-bleed in 80% to 100% of patients and represent a very high-risk group.36 Patients with gastric ulcers have a greater risk of re-bleeding than patients with duodenal ulcers.5 An aggressive approach in these high-risk groups is indicated in order to decrease mortality. The use of endoscopic methods to control hemorrhage may be attempted as the first therapeutic step. These methods include monopolar or bipolar electrocoagulation, laser photocoagulation, and direct application of heat with a "heater" probe. The results of these treatment modalities have been mixed and are clearly operator-dependent. 13, 28, 36, 48 If these methods are unsuccessful or if brisk bleeding precludes the use of these methods, emergency operation must be performed immediately because delay in surgical intervention results in higher patient mortality,43 It should also be pointed out that on occasion, if bleeding is brisk, it may not be possible to adequately resuscitate the patient prior to the operation. In such cases, the patient must be taken to the operating room expeditiously, even if vital signs continue to remain unstable; otherwise, the condition of the patient will continue to worsen, resulting in increasing transfusion requirements and a formidable risk of perioperative mortality. Once the decision to operate has been made, it is very important to gain control of the bleeding vessel as quickly as possible. For a bleeding duodenal ulcer, an anterior duodenotomy is performed with suture ligature of the vessel at the base of the ulcer. Following this step, the choice of operation depends on several factors: location of the ulcer; age, stability, and general medical condition of the patient; and preference of the individual surgeon. For older patients and for those who are hemodynamically unstable, we prefer a truncal vagotomy-pyloroplasty. This procedure can be performed expeditiously and has a lower mortality rate than procedures involVing gastric resection. In younger, lower-risk patients, we recommend truncal vagotomy-antrectomy, with a Billroth I or 11 reconstruction. However, a very scarred duodenum might make this procedure hazardous due to the difficulty in dealing with the duodenal stump. A 1006 AJIT K. SAClIDEYA ET AL. Billroth II procedure might thcn requirc special steps, such as a tube duodenostoll1Y, or closure of the duodenal stump with a RO\lx-en- Y loop of jejunum. A scarred anterior duodenal wall might even make a pyloroplasty technically very difficult to perform. Although proximal gastric vagotomy has been successfully perf()rmed in patients requiring emergency surgery f()r massive hemorrhage,IO, 17 we do not recommend this approach because it prolongs operating time in these critically ill patients. If proximal gastric vagotomy is selected, the patient should be younger, lower-risk, and hemodynamically stable. Thc incidence of early re-bleeding following truncal vagotomy-pyloroplasty has been reported to be 4.3% versus a ratc of 0 ..5% for early re-bleeding following truncal vagotomy-antrectomy.16 For bleeding gastric ulcers located distally, a distal gastrectomy with a Billroth I or 11 reconstruction should be performed in relatively good-risk, stable patients. Since the resected specimen includes the ulcer, this also allows adequate pathologic evaluation of the ulcer. In higher-risk patients, excision of the ulcer with vagotomy-pyloroplasty may be performed. j(j For gastric ulcers located high along the lesser curve, following control of hemorrhage, biopsy of ulcer should be performed along with vagotomypyloroplasty. In very unstable patients, simple suture ligature of the bleeding vessel and biopsy of the ulcer should be considered. 42 Stress Ulceration Stress ulceration is associatcd with a number of risk factors, including sepsis, trauma, shock, and multiple-system failure. Prophylaxis of stress ulceration in these situations (with antacids, Hz-receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, or sucralhtte) and correction of the associated predisposing condition remain the primary methods of patient management. Such regimens have been successfiJl in preventing blecding in 88% to 97% of cases. 56 However, if hemorrhage occurs, and if it is of sufficient magnitude to requirc surgery, mortality rates of 40% to 60% result. Factors contril)uting to high mortality include multiple predisposing causes, massive blood transfusions (17 units or more), rcspiratory failure, and recurrent hemorrhage. 19 When hemorrhage persists, operation should be considercd after transfusion of five to six units of blood. Operation for stress ulceration must be adequate to diminish the incidence of continued or recurrent bleeding that results in high mortality rates. Also, mortality rates correlate more accurately with the general condition of the patient than with the operative procedure performed. Hence, a more aggressive surgical approach is indicated. We recommend a near-total or total gastrectomy for diffuse mucosal ulceration and bleeding. For the few patients with limited distal gastric ulceration, a distal gastrectomy may be adequate. Oespite initial control of hemorrhage following surgery, a significant number of patients are likely to re-bleed. In a retrospective review covering a period of 25 years, Hubert and associates 19 reported recurrent bleeding in 38% of cases following surgery. In poor-risk patients, emergency arteriography and selective embolization might be considered instead of surgery as the initial interventional approach. C sing these techniques, control of hem or rh age has been reported in 79% of cases and recurrent bleeding has been documented in 18% of SUHCICAL TREAT\IE'JT OF PEPTIC ULCEH DISEASE 1007 cases. 9 However, the complication rate for this technique remains quite high, even in experienced hands. Perforation If patients with perforated duodenal ulcer are in shock, they require aggressive resuscitation followed by prompt celiotomy. Preoperatively, nasogastric aspiration is instituted and broad-spectrum antibiotics started. There is still some controversy as to whether these patients should undergo only closure of the perforation with an omental patch or whether a definitive ulcer operation should be combined with closure of perforation. It has been claimed that a prior history of duodenal ulcer disease or findings of chronic ulcer at the time of the operation might identify suitable patients who will bencfit from immediate definitive surgery. However, this approach has been challenged because of the problems associated with obtaining an accurate history and because of the high ulcer recurrence rates reported in some series, irrespective of the duration of ulcer symptoms. In a series reported by Boey and associates, ulcer recurrence rates following simple closure of perforation were 36.6% after 3 years, compared with a 10.6% recurrence rate after definitive surgery (proximal gastric vagotomy). Recurrence rates between 14% and 80% f()lIowing closure of acute ulcers have been reported.:] Authors have reported comparable operative mortality in relatively good-risk patients whether simple closure is performed or a definitive procedure is added. 6 This makes a strong case for the latter approach in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer. 14 Despite the recommendations of some authors who suggest just closure of the perforation, 4. 30 we recommend a definitive procedure unless the patient is poor-risk and has significant peritoneal contamination or unless the peIforation is associated with an acute ulcer caused by drug ingestion or acute stress. The choice of the definitive operation also remains somewhat controversial. In patients with duodenal ulcer perforation, good results have been reported with proximal gastric vagotomy. 3. 21 Alternatively, truncal vagotomy-pyloroplasty may be peIformed. We have used truncal vagotomypyloroplasty quite frequently because its technical ease reduces operating time considerably. Perioperative mortality in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer has been found to be related to preoperative shock, severe concurrent medical illness, and presentation for treatment 24 hours after peIforation. 2 If all three risk factors were present, Boey and associates 2 reported mortality of 100%. Koness and associates 31 reported that patients with perforated ulcer who were older than 5,5 years and those with intraoperative hypotension had a higher mortality. For perforated gastric ulcers, a distal gastrectomy with Billroth I or 11 anastomosis should be undertaken if the ulcer is in the distal stomach and the patient is a good risk. .39 Unlike duodenal ulcers, gastric ulcers present the risk of malignancy. Hence, this procedure has the additional advantage of enabling excision of the ulcer for pathologic diagnosis. In high-risk patients, biopsy of the ulcer should be performed and the ulcer closed with an omental patch. 34 ..51, 53 1008 AJIT K. SACHDEVA ET AL. Obstruction Patients with peptic ulcer disease may present with acute gastric outlet obstruction because of inflammation and edema around a pyloric channel ulcer. Other patients present with a chronic history of ulcer disease that has resulted in scarring of the pyloroduodenal region and thus permanent narrowing. Many patients with permanent narrowing have a long history of ulcer disease, with periodic exacerbations. When thc diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction is made, the patient should be placed on a regimen of nasogastric decompression, intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement, and Hz-receptor antagonists. In patients with acute obstructions, improvement is generally seen within 72 hours. If the patient does not improve, operation should be performed. A slightly longer period of preoperative management may be required if the patient has been significantly depleted of fluid and electrolytes (resulting in severe metabolic problems), or if the patient needs parenteral nutritional support. In younger, better-risk patients, we recommend truncal vagotomyantrectomy, with a Billroth 11 reconstruction. This procedure is very effective and has a low ulcer recurrence rate. In older patients, truncal vagotomy and a drainage procedure should be considered. Delayed gastric emptying following operative procedures has been reported by some authors, but has not been found to be a significant problem by others. 11 Adequate preoperative nasogastric decompression helps to diminish gastric atony and facilitates postoperative gastric emptying. Several recent reports note good results with proximal gastric vagotomy and drainage. b . .37 Also, proximal gastric vagotomy with dilatation has been performed in patients with gastric outlet obstruction. 26 However, the longterm results of dilatation are still questionable. Kozarepz reported immediate symptomatic relief in 67% of patients following endoscopic dilatation. However, objective improvement (radiologically or endoscopically) at 3 months was seen in only 38% of patients. Restricturing after dilatation (surgical or endoscopic) continues to remain a concern. Intractability The availability of effective medication has led to high rates of healing of duodenal ulcers; for example, it is stated that over 80% of patients heal after 4 weeks of starting medical therapy and over 90% of patients heal after 8 weeks. 45 However, once treatment is stopped, 50% to 90% of patients will have a recurrence. 46 Thus, long-term maintenance therapy with H 2 -receptor antagonists is recommended. Medication does not, however, cure the underlying ulcer diathesis, and about 10% of patients will ultimately develop complications (hemorrhage, perforation, or stenosis).46 In some patients, ulcer recurrences are frequent, or ulcers do not respond to the usual medical management. These patients should be considered intractable and therefore candidates for elective surgery.40 Persistence with long-term medical treatment in these cases may result in a high complication rate. Also, a few patients will continue to be noncompliant with medical therapy, and they too should be considered candidates for elective surgical treatment. The cost of long-term maintenance therapy in comparison to the cost of surgery must be considered during treatment of duodenal ulcer SURCICAL TI\EAT\IE]\;T OF PEPTIC CLCEI\ DISL\SE 1009 disease. 'Neighing all these f~lctors, if electivc surgery for duodenal ulcer disease is indicated, we recommcnd proximal gastric vagotomy because of its very low complication rate coupled with a very low incidence of undesirable postoperative side effects (such as dumping or diarrheal. If proximal gastric vagotomy is not advisable for technical reasons, another procedure may be selected. Prior to initiation of medical therapy, a gastric ulcer must be evaluated endoscopically and biopsy perfcmned to assess for possible malignancy. Once medical treatment is begun, close follow-up is required. If the gastric ulcer does not heal within 6 to 8 weeks of placing the patient on medical therapy, we recommend elective surgery. For distal gastric ulcers, a distal gastrectomy should be performed. . . Recurrent Ulceration Recurrent ulceration may occur after a surgical procedure for peptic ulcer disease. The incidence varies according to the type of procedure performed and may be a result of technical error during the original procedure. Examples of technical errors resulting in recurrent ulceration include incomplete vagotomy, inadequate gastric resection, and retained gastric antrum in the duodenal stump following a Billroth 11 reconstruction. If recurrence occurs, other causes such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and hyperparathyroidism must also be considered. The recurrence rate after operations for benign gastric ulcers has been reported to be between 2% and 4%Y Once Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and hyperparathyroidism have been excluded, the patient may be placed initially on medical treatment. Hoffmann reported an 80% rate of healing of recurrent ulcers in patients on H 2 -receptor antagonist therapy after 4 weeks and a 95% rate of healing after 12 weeks of therapy. However, 30% to 75% of patients will develop a new ulcer within 9 months of stopping this treatment. Even on maintenance therapy, up to 50% of patients will develop ulcer recurrence. Generally, 50% of the patients who develop recurrent ulceration will require a second operation. 1R A variety of surgical options must be considered, depending upon the type of original procedure that was performed, the operative findings at the time of that first procedure, the pathology reports fi'om the first procedure, and other diagnostic studies that might provide information on a possible technical error that may have contributed to the recurrence. If the initial procedure was vagotomy and drainage or proximal gastric vagotomy, re-vagotomy and antrectomy should be considered. If the initial procedure was vagotomy-antrectomy, re-vagotomy or further gastric resection may have to be performed.1.5 If there is stenosis of the gastroenteric anastomosis, this should be revised at the time of reoperation. If there is no reason to go into the abdomen other than to perform re-vagotomy, it is technically much easier and safer to perform the vagotomy through the transthoracic route, away from adhesions from previous surgery.49 For recurrent gastric ulceration, further gastric resection may need to be performed. The specific operative procedure for recurrent ulceration depends on the requirements of the individual patient. 1010 AJIT K. SACHDEYA ET AL. SUMMARY Elective surgery for peptic ulcer disease has diminished significantly over the past 15 years. However, emergency surgery has not shown a decline. Some series have even reported an increase in hospitalizations and operations for hemorrhage. The appropriate surgical procedure for peptic ulcer disease must be tailored to the specific needs of the individual patient. During emergency operations for hemorrhage from duodenal ulcer, we recommend suture ligature of the bleeding vessel and vagotomypyloroplasty for high-risk patients, or vagotomy-antrectomy for the lowerrisk patient. Bleeding gastric ulcers should be resected, if possible. For massive hemorrhage from stress ulceration requiring surgery, near-total or total gastrectomy should be performed. Perforated duodenal ulcers are best managed by closure and a definitiye ulcer operation, such as vagotomy-pyloroplasty. Perforated gastric ulcers are best excised but may be simply closed if conditions do not favor resection. In these situations, biopsy should be performed. \Ve recommend truncal vagotomy-antrectomy for patients presenting with obstruction. Vagotomy (truncal or proximal gastric) with drainage is an acceptable alternative in this situation. For patients with intractable ulcer disease or for those who are noncompliant, proximal gastric vagotomy is the preferred operation. Howeyer, other operations may need to be considered, depending on the specific situation. Recurrent ulceration needs appropriate work-up to determine the possible cause. Although patients with ulcer recurrence initially may be placed on medical treatment, about 50% will require reoperation. The most effective procedure for peptic ulcer disease is truncal vagotomy-antrectomy, which has a recurrence rate of less than 1%. The procedure with the least morbidity and the fewest undesirable side effects is proximal gastric vagotomy. Ulcer recurrence after proximal gastric vagotomy or truncal vagotomy-pyloroplasty is in the range of 10% to 15%. ACKNOWLEDCl\IEKTS The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Juliette K. Smith, who prepared the illustrations for Figures 1 through 4, and Maureen Benzing, who assisted in preparation of the manuscript and provided technical editing. REFERENCES 1. Bardhan KD, Cust C, HinchlifI"e RFC, et a1: Changing pattern of admissions and operations for duodenal ulcer. Br J Surg 76:230, 1989 2. Boey J, Choi SKY, Poon A, et al: Risk stratification in perforated duodenal ulcers: A prospective validation of predictive factors. Ann Surg 205:22, 1987 3. Boey J, Branicki FJ, Alagaratnam TT, et al: Proximal gastric vagotomy: The preferred operation ft)r perf()rations in acute duodenal ulcer. Ann Surg 208:169, 1988 4. Bormnan PC, Theodorou NA, Jeflery PC, et a1: Simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer: A prospective evaluation of a conservative management policy. Br J Surg 77:73, 1990 SCI\CIC\L THKH"!E".;T OF PEPTIC l'LCEH DISEASE 1011 5. Brearlev S, Hawker PC, ~lorris DL, et al: Selection of patients f()r surgerv f()llowing pepti~· ulcer haemorrhage. Br J Surg 74:H9:3, 19H7 6. Christiansen J, Andersen OB, Bonnesen 1', et al: Perf(m,ted duodenal ulcer managed bv simple closure versus closure and proximal gastric vagotomv, Br J Surg 74:286, 19H7 " Clason AE, Macleod DAD, Elton RA: Clinical hlctorS in the prediction of hlrther haemorrhage or mortality in acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg 73:985, 19H6 8. Donahue PE, Yoshida J, Richter HM, et al: Proximal gastric vagotomy with drainage ft)r obstructing lluodenal ulcer. Surgery 104:7.57, 19H8 9, Eckstein 1\1R, Kelemouridis V, Athanasoulis CA, et al: Gastric bleeding: Therapy with intraarterial vasopressin and transcatheter emholization, Hadiology 1.52:643, 1984 10, Falk CL, Hollinshead JW, Cillett DJ: Highly selective vagotomy in the treatment of complicated duodenal ulcer. Med J Austr 152:574, 1990 11. Fisher HD, Ebert PA, Zuidema CD: Obstructing peptic ulcers. Arch Snrg 94:724, 1967 12, Fromm D: Ulceration of the stomach and duodenum, In Fromm D (ed): Castrointestinal Surgery, New York, Churchill Livingstone, 198.5, p 23:3 1:3. Fullarton GM, Birnie CG, \laedonald A, et al: Controlled trial of heater probe treatment in bleeding peptic ulcers. Br J Surg 76:541, 191)9 14. Hay JM, Lacaine F, Kohlmann C, et al: Immediate definitive surgery f()r peri,)rated duodenal ulcer does not increase operative mortality: A prospective controlled trial. World J Surg 12:705, 1988 ],5, Hprringtoll JL, Bluett MK: The surgical management of recurrent ulceration, Conternp Surg 28:1.5, 191)6 16, Herri,;gton JL, Daddson J: Bleeding gastroduodenal ulcers: Choice of operations, \Vorld J Surg 11::304, 191)7 17, Hoflil1'UlI1 L Devantier A, Koelle T, et al: Parietal cell vagotomv as an emergency procedure for bleeding peptic ulcer. Ann Surg 206:.58:3, 19S7 11). Hoffmann J, Shokouh-Amiri MH: Treatment of recurrent ulceration after vagotomy flll' duodenal ulcer. Acta Chir Scam! 547(suppll:82, 1988 19, Hubert JP, Kiernan PD, \Velch JS, et al: The surgical management of hleeding stress ulcers. Ann Surg 191:672, 1980 20, Hunt PS: Bleeding gastroduodenal ulcers: selection of patients for surgery, \Vorld J Surg 11:2H9, 19S7 21. Jamicson GG: Should we be changing our operative strategies for the acute complications of peptic ulcer disease? Aust NZ J Surg .58:.525, 1988 22, Jensen 1\10, Buhrick MP, Onstad GH, et al: Changes in the surgical treatment of acid peptic disease. Am Surg 51:.5,56, 198.5 2:3. Johnston D: Duodenal and gastric ulcer. In Schwartz SI, Ellis H (eds): :Vlaingot"s Abdominal Operations, cd H, '\iorwalk, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1985, p 741 24, Johns(on D: Operative technique of highly selective (parietal cell) vagotomy, Acta Chir Scand 547(suppl):49, 191)tl 2.5. Johnstoll D, B1ackett HL: Hecurrent peptic ulcer. World J Surg 11:274, 191)7 26, Johnston D, Lyndon PJ, Smith HB, et al: Highlv selective vagotomy without a drainage procedure in the treatment of haemorrhage, perforation, amI pyloric stenosis due to peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 60:790, 1973 27, Johnston JH: The sentinel clot and invisible vessel: Pathologic anatomy of hleeding peptic ulcer (editorial), Gastrointest Endosc :30::31:3, 19H4 2S. Johnston Jll, Sones JQ, Long BW, et al: Comparison of heater probe and YAG laser in endoscopic treatment of major bleeding from peptic ulcers, Gastrointest Endose :31:17.5, 191),5 29. Kennedy 1', Connell AM, Love AHG, et al: Selective or truncal vagotomy? Br J Surg 60:944, 1973 :30. King 1''>1, Hoss AHMcL: Perforated duodenal ulcer: Long-term results of omental patch closure, J Royal Coli Surg Edin :32:79, 191)7 :31. Koness RJ, Cutitar M, Bmchard K\V: Perf<lrated peptic ulcer: Determinants of morbidity and mortalitv, Am Surg .56:21)0, 1990 32, Kozarek RA: Hvdrostatic-balloon dilation of gastrointestinal stenoses: A national survey, Gastrointest Endosc :32:15, 1986 3:3. Kurata JH, Corboy ED: Current peptic ulcer time trends, J Clin Castroentcrol 10:259, 1981) 1012 AJIT K. SACIIDEYA ET AL. :34. Lanng C, Palnaes Hansen C, Christensen A, et al: Perf(mlted gastric ulcer. Br J Surg 7.5:7.58, 1988 3.5. Larson G, SC'lllnidt T, Gott J, et al: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Predictors of outcome. Surgery 100:76.5, 1986 36. Laurence BH, Cotton PB: Bleeding gastroduodenal ulcers: Nonoperative treatment. World J Surg 11:295, 1987 37. Lunde 0, Liavag I, Roland M: Proximal gastric vagotomy and pyloroplasty for duodenal ulcer with pyloric stenosis: A thirteen-year experience. World J Surg 9:165, 198.5 38. McConnell DB, Baba GC, Deveney CW: Changes in surgical treatment of peptic ulcer disease within a veterans hospital in the 1970s and the 1980s. Arch Surg 124:1164, 1989 39. McGee GS, Sawyers JL: Perforated gastric ulcers. Arch Surg 122:5.5.5, 1987 40. ~Iulholland MW, Dellas HT: Chronic duodenal and gastric ulcer. Surg Clin North Am 67:489, 1987 41. Hheault ~IJ, Legros G, Nyhus L: Reflux gastritis. Dig Surg 5:5, 1988 42. Rogers PN, Murrav WH, Shaw R, et al: Surgical management of bleeding gastric ulceration. Br J Surg 75:16, 1988 43. Roher HD, Thon K: Impact of early operation on the mortality from bleeding peptic ulccr. Dig Surg 1:32, 1984 44. Schinner BD: Current status of proximal gastric vagotomy. Ann Surg 209:131, 1989 4,5. Simon B, Porro GB, Cremer M, et al: A single nighttime dose of ranitidine 300 mg versus ranitidine 1.50 mg twice daily in the acute treatment of duodenal ulcer: A European multicenter trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 8:367, 1986 46. Sontag S: Current status of maintenance therapy in peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol 83:607, 1988 47. Stabile BE, Passaro E Jr: Progress in gastroenterology: Recurrent peptic ulcer. Gastroenterology 70: 124, 1976 48. Steele RJC: Endoscopic haemostasis for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage (review). Br J Surg 76:219, 1989 49. Thirlhy HC, Feldman ]\\: Transthoracic vagotomy for postoperative peptic ulcer. Ann Surg 201 :648, 198.5 50. Thompson JC: The stomach and duodenum. In Sabiston DC (ed): Textbook of Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saul1l1ers, 1986, p 810 .51. Thurston OG: Perforated benign gastric ulcer: The case for simple closure. Can J Surg 32:94, 1989 52. Toftgaard C: Gastric cancer after peptic ulcer surgery: A historic prospective cohort investigation. Ann Surg 210: 159, 1989 .53. Turner WW, Thompson WM, Thai EH: Perforated gastric ulcers. Arch Surg 123:960, 1988 .54. Walker LG: Trends in the surgical management of duodenal ulcer. Am J Surg 1.5.5:436, 1988 .55. Wastell C: Proximal gastric vagotomy. In Nyhus LM, Wastell C (eds): Surgery of the Stomach and Duodenum, ed 4. Boston, Little Brown and Company, 1986, p 36.5 56. Zuckerman GH, Shuman H: Therapeutic goals and treatment options for prevention of stress ulcer syndrome. Am J ~Ied 83:29, 1987 Address reprint requests to Ajit K. Sachdeva, MD Department of Surgery The Medical College of Pennsylvania 3300 Henrv Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19129