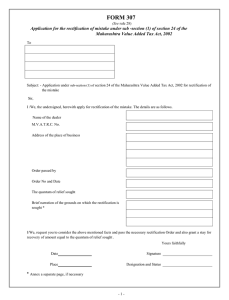

RECTIFICATION OF MISTAKE

BY SUHRID BHATNAGAR, B.Sc., MBA(Exe.), EPGDM (IIM-I), LL.B., LL.M.

Partner, Acumen Tax Consultants, Jaipur

A.

IN SERVICE TAX

A Central Excise Officer, after passing an order becomes functus officio and the order passed by

him become ‘final’ to the extent that it cannot be modified by him so as to affect changes therein,

subject to something to the effect provided by law.

While the orders of an adjudicating authority (Central Excise Officer) are reviewed by the

designated departmental reviewing authority, a power of amendment to the same by the

adjudicating authority himself lies to a limited extent in section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994

which provides for ‘rectification of mistake’.

1.

WHO CAN RECTIFY THE MISTAKE

Subsection (1) of section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994 reads as under:

(1)

With a view to rectifying any mistake apparent from the record, the

Central Excise Officer who passed any order under the provisions of this Chapter

may, within two years of the date on which such order was passed, amend the

order.

Therefore, section 74(1) provides that only the Central Excise Officer, who passed the order

under the provisions of Finance Act, 1994, can rectify the mistake. However, it is very much

probable that the officer who had passed the order might have been transferred, promoted or

retired. In such cases, can the successor Central Excise Officer rectify the mistake?

The answer to this question was given by Calcutta High Court in the case of Sushil Chandra

Ghosh v. Income Tax Officer (AIR 1958 Cal 159) where the rectification order was challenged

on the ground that the order was rectified by the successor officer. The High Court in that case

did not find any infirmity in the order since section 35 of the Income Tax Act at that material

time did not have anything to that effect.

Even in section 74, only the word Central Excise Officer is used, and it can be taken to also

include any succeeding Central Excise Officer. Therefore, even for the purpose of this section

“Central Excise Officer who passed the order” is taken to mean the designation of the

adjudicating authority and not the particular person.

2.

WHO CAN AGITATE THE RECTIFICATION PROCEEDING

As per subsection (3) of section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994, the Central Excise Officer may

make amendment to the order passed by him:

1

a) on his own motion i.e. by himself, or

b) if any mistake is brought to his notice by

i. the assessee, or

ii. Commissioner of Central Excise, or

iii. Commissioner of Central Excise (Appeals)

Therefore, in respect of an order passed by a Deputy / Assistant Commissioner or Additional /

Joint Commissioner, their reviewing as well as first appellate authorities are also empowered to

bring into notice the mistake so that the said Deputy / Assistant Commissioner or Additional /

Joint Commissioner can rectify the mistake under section 74(3). However, the section lacks in

the sense that it does not elaborately cover the cases where the order has been passed by the

Commissioner for which reviewing authority is the jurisdictional Chief Commissioner and

appellate authority is CESTAT.

3.

WHAT CAN BE RECTIFIED

As per subsection (1) of section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994, only a mistake apparent from the

record can be rectified by way of amending the order.

Further, as per subsection (2) of section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994, even if the matter has been

considered and decided in any proceeding by way of appeal or revision relating to the order

requiring the amendment, the Central Excise Officer passing such order may, notwithstanding

anything contained in any law for the time being in force, amend the order under sub-section (1)

in relation to any matter other than the matter which has been so considered and decided.

4.

WHAT IS ‘MISTAKE APPARENT FROM THE RECORD’

The phrase ‘mistake apparent from the record’ has not been defined in the Finance Act, 1994.

However, to find as to what is a ‘mistake apparent from the record’, we have to look at various

case laws, most of which relate to Income Tax.

In TS Balaram, ITO v. Volkart Brothers, Bombay {(1971) 2 SCC 526} it has been held by the

Supreme Court that “a mistake apparent on the record must be an obvious and patent mistake and

not something which can be established by a long drawn process of reasoning on points on which

there may conceivably be two opinions.”

In Gammon India Limited v. Commissioner of Income-Tax {1995 214 ITR 50 Bom} ‘mistake

apparent from the record’ has been discussed in elaborate details and while relying upon the

aforesaid case of TS Balaram, ITO, it has been held by the Bombay High Court that

“Besides, it must be a mistake which is patent on the face of the record and does not call

for detailed investigation of the facts or require an elaborate argument to establish it. It

does not cover any mistake which may be discovered by a complicated process of

investigation, argument or proof. The mistake sought to be rectified must be manifest and

self-evident on the face of the record. It must be one which is apparent and not lurking,

which is visible and not dormant, which can be seen and not hidden. It cannot be

2

demonstrated to exist by relying upon materials outside the record. A decision on a

debatable point of law or failure to apply the law to a set of facts which remain to be

investigated cannot be corrected by way of rectification. The legal position is thus now

settled that a mistake which is not obvious, patent and self-evident and mistake on which

conceivably there can be two opinions cannot be rectified by way of rectification of

mistake under section 154 of the Act. In other words, in the garb of exercise of the power

of rectification under section 154 of the Act, the income-tax authorities cannot revise or

review their order generally or reconsider the conclusions arrived therein on the facts

before them at that time on the basis of new facts brought on record by the party seeking

rectification or coming into possession otherwise, because the jurisdiction under section

154 is confined to rectification of mistakes apparent from the record.”

It is also worthwhile to note here that the term ‘record’ has not been defined in the Finance Act,

1994. Only the term ‘specified records’ is provided in the explanation to Section 73(4A) of the

Finance Act, 1994 (which is proposed to be omitted by clause 110 of the Finance Bill, 2015)

which is not relevant here. In the above case of Gammon India Limited, the High Court also

held that:

“‘Record’ in such a case would mean record of the case comprising the entire

proceedings including documents and materials produced by the parties and taken on

record by the authorities which were available at the time of passing of the order which

is the subject-matter of proceedings for rectification. They cannot go beyond the records

and look into fresh evidence or materials which were not on record at the time the order

sought to be rectified was passed.”

In Batuk K. Vyas v. Surat Municipality {ILR 1953 Bom 191 : AIR 1953 Bom 133}, it was held

that no error can be said to be apparent on the face of the record if it is not manifest or selfevident and requires an examination or argument to establish it.

In the leading case of Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Syed Ahmad Ishaque {(1955) 1 SCR 1104}, the

Constitution Bench of this Court quoted the observations of Chagla, C.J. in aforesaid Batuk K.

Vyas case and admitted that though the said test might apply in majority of cases satisfactorily,

however, the court proceeded to comment that there might be cases in which it might not work

inasmuch as an error of law might be considered by one Judge as apparent, patent and selfevident, but might not be so considered by another Judge. The Court, therefore, concluded that

an error apparent on the face of the record cannot be defined exhaustively there being an element

of indefiniteness inherent in its very nature and must be left to be determined judicially on the

facts of each case.

In CIT v. Harnand Roy Shrikishan A. Kodia {(1966) 61 ITR 50 (MP)}, it was held that a mistake

will not be a mistake apparent from record if it required extraneous evidence to be brought in for

rectifying that mistake. Rather, a mistake apparent from record should be shown to be a mistake

that can be gathered from the records of the case.

In CTO v. Sri Venkateswara Oil Mills {(1974) 3 SCC 5: (1973) 32 STC 660 (SC)}, it was held

that a decision on a debatable point of law is not a mistake apparent from record. Thus a

3

“mistake apparent on record” must not be something which can be established by a long drawn

process of reasoning on points on which there may be conceivably two opinions.

In N. Rajamoni Amma v. Dy. CIT {(1990) 86 CTR 12 (Ker)}, it was held that a decision on the

debatable point of law or fact or failure to apply the law to a set of facts which remain to be

investigated cannot be corrected by rectification. However, a glaring and obvious mistake of law

not requiring long drawn process of reasoning can be rectified as a mistake apparent from record

as held in M.K. Venketachalam v. Bombay Dyeing & Mfg. Co. Ltd. {AIR 1958 SC 875: (1958)

34 ITR 143 (SC)}. In this case certain assessments became erroneous because Parliament

enacted an amendment with retrospective effect. These assessments were taken to be suffering

from a mistake apparent from the record.

In CIT v. Kesri Metal Private Limited {AIR 1999 SC 3801, 1999 237 ITR 165 SC, JT 1999 (3)

SC 45, (1999) 9 SCC 165}, it has been held by the Supreme Court that “a look at the record must

show there has been an error, and that error may be rectified.”

In ACIT v. Saurashtra Kutch Stock Exchange Ltd. in Civil Appeal No. 1171 of 2004, the

Supreme Court on September 15, 2008 opined that non-consideration of a decision of

Jurisdictional Court or of the Supreme Court can be said to be a "mistake apparent from the

record" which could be rectified.

In Deva Metal Powders (P) Limited v. Commissioner, Trade Tax, Uttar Pradesh, reported in

2008 (2) S.C.C.439, the Supreme Court held that a `rectifiable mistake' must exist and the same

must be apparent from the record. It must be a patent mistake, which is obvious and whose

discovery is not dependant on elaborate arguments.

In Commissioner of Central Excise, Calcutta v. A.S.C.U. Limited [2003 (151) E.L.T. 481 (SC)],

it was held that a `rectifiable mistake' is a mistake which is obvious and not something which has

to be established by a long drawn process of reasoning or where two opinions are possible.

Decision on debatable point of law cannot be treated as "mistake apparent from the record".

In Onkar Travels (P) Ltd. v. CCE, Jalandhar [2006 (3) S.T.R. 164 (Tri. - Del.)], it has been held

that when assessment under section 71 of Finance Act, 1994 is done finally, it cannot be said that

there was an error and appellant did not produce relevant records. [Maintained in 2008 (10) STR

237 (Punjab & Haryana High Court)]

In Force Seven Security v. CCE (2007) 8 STT 10 (CESTAT) it has been held that rectification of

order pertains to certain clerical or arithmetic mistakes and not of revising the order.

In Gujarat Security Services v. CST(2008) 13 STT 166 (CESTAT SMB), it has been held that

mistake that can be rectified may be arithmetical, typographical or calculation mistake. By no

stretch of imagination, it can be extended to an interpretation of provision of law.

5.

LIMITATION:

4

As per subsection (1) of section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994, for rectification of mistake apparent

from the record, the Central Excise Officer may amend the order within two years of the date on

which such order was originally passed. The section does not provide for condonation of delay,

and therefore it has to be within two years from the date of passing the order that such an order

be amended for rectification of mistake apparent from the record. Therefore, such mistake has to

be brought to the notice of the Central Excise Officer well in time, so that if so necessitates, he is

allowed time to give notice and a reasonable opportunity to be heard to the assessee.

6.

MANNER OF PASSING THE AMENDING ORDER

6.1

The amending order by the Central Excise Officer may have an impact either way, i.e. it

can enhance the liability of the assessee or reduce the refund to the assessee, or it can reduce the

liability of the assessee or increase the refund to the assessee.

6.2

In terms of subsection (4) of section 74, if the amendment has effect of enhancing the

liability of the assessee or reducing a refund, the order shall be made only after giving a notice to

the assessee of his intention so to do and after allowing the assessee a reasonable opportunity of

being heard. In nutshell, if the effect of the order is adverse to the interests of the assessee, the

principle of natural justice must be followed. In terms of subsection (5), for making the

amendment to the original order, the Central Excise Officer shall pass an order in writing

wherein, in terms of subsection (7), the sum payable by the assessee shall be specified.

The section is not explicit enough to speak that in case of increase / decrease in liabilities and

decrease / increase in refund, what shall happen to the penalties already imposed. Subsection (7)

only speaks that “and the provisions of this Chapter shall apply accordingly”, which implies that

along with enhancing the liability, the applicable penalties which depend upon the quantum of

liability may also be enhanced accordingly, wherever applicable.

In Force Seven Security v. CCE (2007) 8 STT 350 (CESTAT SMB), it was held that rectification

proceedings cannot be used to enhance penalty already imposed. Proper course is for

Commissioner to use revisionary powers. However, this case pertains to the period when the

Commissioner used to issue Orders-in-Revision in service tax cases.

6.3

In terms of subsection (4) of section 74, if the amendment has the effect of reducing the

liability of the assessee or increasing the refund, the Central Excise Officer shall make any

refund which may be due to such assessee.

There is no doubt here that such refund shall be consequential in nature. The important question

here is as to what shall be the relevant date from which limitation for filing the refund shall

apply. None of the categories given in Explanation (B) to Section 11B of Central Excise Act,

1944 defining the ‘relevant date’ pertains to the amending orders passed by the Central Excise

Officer for rectification of mistake under section 74 of the Finance Act, 1994. The closest entry

which is found is clause (ec) to the said explanation which pertains to the cases where the duty

becomes refundable as a consequence of judgment, decree, order or direction of appellate

authority, Appellate Tribunal or any court and the relevant date in such cases is the date of such

judgment, decree, order or direction. However, it does not mention the orders for rectification of

mistake passed by the original adjudicating authorities under section 74 of the Finance Act,

5

1994. The last entry is clause (f) which speaks ‘in any other case, the date of payment of duty’,

and therefore if this entry is taken into account, the refunds are more than likely to be hit by

limitation.

7.

PROBABLE MISUSE OF THIS PROVISION

In cases where limitation for appeal has expired, the assessee may take recourse to this provision

by contending some mistake in the order. However, it is to be carefully seen by the Central

Excise Officer that such mistake should be apparent from the record of the proceedings itself,

and the attempt of the assessee to introduce any new or extraneous document / evidence may be

turned down.

In the case of Onkar Travels (P) Ltd. v. CCE, Jalandhar reported at 2006 (3) S.T.R. 164 (Tri. Del.), it has been held that if an appeal is not filed within time under Section 85 ibid, opportunity

to re-open assessment cannot be read into provisions of Section 74 ibid. [Maintained in 2008

(10) STR 237 (Punjab & Haryana High Court)]

In KP Dinakaran v. CCE (2007) 9 STT 277 (CESTAT), it has been held that in guise of

rectification of mistake, entire complexion of order cannot be altered under section 74. Proper

course of action will be revision by Commissioner under section 84.

In Girnar Impex v. State of Punjab (2009) 20 STT 477 (P&H HC DB) it has been held that fresh

issue cannot be taken in rectification proceedings.

8.

OTHER ISSUES

8.1

There is no restriction in section 74 upon the number of amending orders that can be

passed by the Central Excise Officer. Therefore, the Central Excise Officer may issue more than

one amending orders. Again, such mistakes should be apparent from the record and the

amending orders must be passed within the limitation of two years from the date of the original

order.

B.

IN CENTRAL EXCISE

There is no provision for rectification of mistake by the Central Excise Officer in Central Excise

Act, 1944.

C.

BY COMMISSIONER (APPEALS)

There is no provision for rectification of mistake by the Commissioner (Appeals) in Central

Excise under Central Excise Act, 1944 or in Service Tax under Finance Act, 1994.

D.

BY APPELLATE TRIBUNAL

1.

As per section 35B(7) of the Central Excise Act, 1944, every application made before the

Appellate Tribunal for rectification of mistake shall be accompanied by a fee of five hundred

6

rupees, provide that no such fee shall be payable in the case of an application filed “by or on

behalf of the Commissioner of Central Excise under this sub-section”.

2.

As per section 86(6A) of the Finance Act, 1994, every application made before the

Appellate Tribunal for rectification of mistake shall be accompanied by a fee of five hundred

rupees, provide that no such fee shall be payable in the case of an application filed “by the

Commissioner of Central Excise or Assistant Commissioner of Central Excise or Deputy

Commissioner of Central Excise, as the case may be under this sub-section.”

3.

In terms of section 86(7) of the Finance Act, 1994, the in respect of hearing the appeals

and making orders under the section 86, the Appellate Tribunal shall exercise the same powers

and follow the same procedure as given in Central Excise Act, 1944. Such powers and

procedures are given in Section 35C of the Central Excise Act, 1944.

4.

Further, section 35C(2) of Central Excise Act, 1944 provides that:

“(2) The Appellate Tribunal may, at any time within six months from the date

of the order, with a view to rectifying any mistake apparent from the record,

amend any order passed by it under sub-section (1) and shall make such

amendments if the mistake is brought to its notice by the Commissioner of

Central Excise or the other party to the appeal:

Provided that an amendment which has the effect of enhancing an

assessment or reducing a refund or otherwise increasing the liability of the

other party, shall not be made under this sub-section, unless the Appellate

Tribunal has given notice to him of its intention to do so and has allowed him

a reasonable opportunity of being heard.”

Therefore, it emanates from the above that limitation for rectifying the mistake apparent from the

record is six months from the order of the Tribunal. Such mistake may be brought to the notice

of the Tribunal by the Commissioner of Central Excise or the other party to the appeal. Also, an

amendment which has the effect of enhancing an assessment or reducing a refund or otherwise

increasing the liability of the other party can be made only after giving a notice to the assessee

and also allowing him a reasonable opportunity of being heard.

Further, the meaning of the phrase ‘‘mistake apparent from the record’ shall carry the same

meaning as decided by appellate tribunals and courts as discussed in detail above.

5.

In the case of Sirpur Paper Mills v. CCE [1986 (24) E.L.T. 49], Saurashtra Cement and

Chemical Industries [1987 (29) E.L.T. 87], M.C. Desai v. Collector [1991 (56) E.L.T. 425] and

National Rayon Corporation Ltd. [1993 (67) E.L.T. 186], the Tribunal has held that rectification

of an earlier order of the Tribunal cannot be made on the basis of a later order interpreting

relevant provisions differently.

7

In Gujarat State Fertilizers and Chemicals Ltd. v. Commr. Of C. Ex., Vadodara [2000 (122) ELT

282 (Tri LB)], again the issue referred to the Larger Bench was as to whether a subsequent

decision of the Tribunal or a High Court or the Supreme Court can form the basis for

rectification of mistake in terms of Section 35C(2) of the Central Excise Act, 1944. While the

counsel of the appellants had contended that a subsequent decision of the Supreme Court is a

ground for recalling the Tribunal's final order for rectification of mistake apparent from record,

the Larger Bench, relying on the above said case laws, held that a subsequent decision of the

Tribunal cannot form the basis of rectification of a mistake in terms of the section 35C(2) of the

Central Excise Act, 1944.

However, the above case was overruled in the case of Hindustan Lever Ltd. v. Commissioner of

C.Ex., Mumbai-I [2008 (10) STR 91 (Tribunal LB)] and it was held that:

“Rectification of mistake - When Supreme Court pronounces on true position of law, any

decision rendered by any other authority contrary to that, is required to be regarded as

an error which is apparent on record and rectification of such an error within period

permissible under law and in accordance with provisions of statute was required to be

effected, as held by Madras High Court in case of V. Guard Industries Ltd. - Section

35C(2) of Central Excise Act, 1944.”

In the same case, it was also held that:

“Rectification of mistake - When a decision rendered by Apex Court is not considered,

non-consideration of such binding precedent would constitute an error apparent on face

of record by applicability of doctrine of per incuriam - Though in context of decisions of

Apex Court and jurisdictional High Courts which are rendered after order of Tribunal,

the doctrine of per incuriam cannot be invoked, yet these would be error apparent from

record of such order on reasoning that superior court declared law as it always was and

question whether there was error apparent from record of order, would still arise Section 35C(2) of Central Excise Act, 1944.”

6.

As for limitation of six months for filing application for rectification of mistake in

CESTAT, in Commissioner of Central Excise, Pune-III v. GE Medical Systems [2013 (29)

S.T.R. 327 (Kar.)] following has been held:

“Appeal to High Court - Scope of - Finding of CESTAT that ROM application was filed

beyond six months period prescribed in Section 35C(2) of Central Excise Act, 1944 HELD : Even if it is question of law, there being no error in it, appeal to High Court is

not maintainable against it - It is more so when law in that respect had already been

declared by Supreme Court - Section 35G of Central Excise Act, 1944 as applicable to

Service Tax vide Section 83 of Finance Act, 1994.”

8

“Rectification of mistake - Limitation - It cannot go beyond prescribed period of six

months from date of order - On facts, ROM application filed beyond six months of

CESTAT order, but within that period from date of its receipt - Rejection of ROM

application by CESTAT, upheld - Section 35C(2) of Central Excise Act, 1944.”

Therefore, looking at the above provisions of law, it emerges that power of ‘rectification of

mistake’ lies with the Central Excise Officer is service tax cases only and with the Appellate

Tribunal in respect of service tax as well as central excise cases. The power is an important tool

to fix any errors which are apparent from the record.

(The views expressed in the article are strictly personal)

9