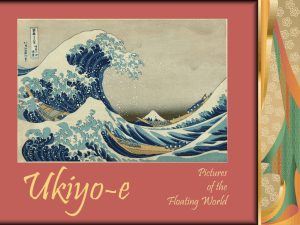

James Zhu ARTS1107.01 Prof. Brian Reeves Systematic Art Analysis 12/14/20 Hiroshige’s Japanese Sunset through the Centuries In 1853, Captain Matthew Perry of the United States Navy sailed into Japan aboard his steam powered ships. The Japanese, amazed by the strength of Perry’s naval fleet, soon realised the power of western technology and Japan’s need for industrialisation. Perry’s visit helped to usher in the Meiji Restoration— a series of economic and military reforms that helped Japan industrialise and rise to world power status. As factories and mines sprawled up around Tokyo, gone was the old landscape of the Japanese countryside. The blue skies, so often featured in traditional Japanese paintings, were contaminated by the black chimney smokes and became a product of the past. That’s why Hiroshige’s work remains influential almost two centuries later. His woodcut prints still present a piece of Japanese history and give viewers a sense of nostalgia and peacefulness. Hiroshige created visual harmony on paper by using popular Ukiyo-e techniques in colour, line strokes and composition. This paper will analyse “Fuji on the Left of the Tōkaidō Road” (東海堂左り不⼆) as a part of Hiroshige’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” Series (富⼠三⼗六景). Utagawa Hiroshige was a Japanese woodcut print artist who lived in the Edo Period in Japan during the early 19th Century. Hiroshige’s style could be described by the word “Ukiyo-e” which could be interpreted as “pictures of the floating world”.1 Ukiyo-e was focused on narrating scenes from every facet of Japanese life from the teahouse to the battlefield. It is unlike more religious oriented paintings from earlier Japanese history. A key signature of the Ukiyo-e style is the use of vibrant and bright colours to illuminate the improving quality of life in late Edo Period Japan.2 “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” is a great representation of Hiroshoge’s works in Ukiyo-e style.3 The rich pigments immortalised the scenes around Mt.Fuji, a prominent Japanese cultural symbol. “Fuji on the left of the Tōkaidō Road” captures a sunset near a small Japanese village far away from the bottom of Mount Fuji. Three trees make up the foreground, providing shade for two villagers walking parallel to Tōkaidō road. The road continues beyond the vertical frame of the wood print, and the travellers lead the viewer’s gaze past the picture and into an imaginary world off screen. One villager is looking to his left and marvelling at Mount Fuji in the far distance. Right beneath the pastel yellow road, lies a lush and turquoise farmland, extending as far as the eye can see towards Mount Fuji and the forest that lies beneath the mountain. 4 farmers labour in the field in traditional Japanese clothing. Near the edge of the farm and forest, 5 bright straw huts stand out from its surroundings. Perhaps the residences of the farmers, the houses represent a community where humans can coexist with the nature nearby. Mount Fuji sits in the “Ukiyo-E”, Artsy, Accessed November 29th, 2020, https://www.artsy.net/gene/ukiyoe#:~:text=Literally%20meaning%20%E2%80%9CPictures%20of%20the,romantic%20landscapes%2C% 20and%20erotic%20scenes. 1 “Ukiyo-E Japanese Prints”, The Art Story. Accessed November 29th, 2020, https://www.theartstory.org/ movement/ukiyo-e-japanese-woodblock-prints/ 2 3 For more information on Hiroshige’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”, visit “The Woodblock Prints of Utagawa Hiroshige”, Hiroshige.org. Accessed December 1st, 2020, https://www.hiroshige.org.uk/ Tokaido_Series/Tokaido_Series.htm very background of the painting and the tip of the mountain blends into a royal blue sky. The only source of light is from the orange sunset. The sun peeks over the mountains slightly. The painter’s perspective looks down at the villagers and farmers while the angle tilts up at Mount Fuji far away. The painter’s perspective is as if he was sitting on a small dirt hill just to the side of the road and soaking in the scenery. The viewer can only imagine what the painter was thinking when he created this piece. However, the same serene feeling of observing a countryside sunset has transcended through time. The composition of the artwork helps Hiroshige achieve visual cohesiveness. Every object in the frame appears to be placed purposefully. The straw huts in the background, for example, are closely placed with each other to achieve togetherness and unity. Analysing through the lens of gestalt principles, one can see that Hiroshige was an avid user of repetition. The sharp thin lines on the grass field and the use of thicker strokes in the midway point of the image all help to create a visual balance. The sharp lines give the grass field a sense of depth while the thicker strokes emphasise the texture of the forest, making the trees appear thick and luscious. The artwork is also continuous and fluid. Every element in the image acts as an arrow that directs the viewers’ eyes. For example, the trees and branches stand from the bottom of the print to the top. As the audience’s eyes move up the painting, they naturally follow the trees and branches onto other elements and layers of the picture. Because one object can continuously lead to the following, every feature appears to be in order within the frame. The colour palette and line strokes both construct the spatial system within the artwork. Traditional Ukiyo-e style prints implement precise lines and flat colours to create clearcut outlines on the page. In “Fuji on the left of Tōkaidō Road”, both techniques are evident. Mount Fuji, the highlight of the print, blends into the beige colour of the canvas because of its snowy peak. However, through a few clean lines, Hiroshige created an obvious outline for the mountain and made it appear distant in the sky. The usage of distinct colours also shaped the print’s dynamic. Where outlines were not separated by a fine line, the artist painted a series of analogous colours to imitate the same effect. From the grass field to the vegetated hills, Hiroshige printed various shades of green and turquoise to produce space on paper and mimic the different levels of light reflected by the plants’ surfaces. Unlike western artists from the renaissance, traditional Chinese and Japanese artists rarely spawn shadows to construct a dimensional image. True to its Asian heritage, Hiroshige’s clear lines and non-contrasting colours heightened the realism of the painted world by fabricating a deeper spatial sense. Hiroshige’s work exists within the context of a revolutionary period of Japanese history and art. Hiroshige, while working for the Japanese magistrate, had the privilege of touring the Japanese countryside. He created “The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” during his journey through a blend of imagination and memory to display the beauties of Japan to the average Japanese citizen.4 Ukiyo-e was an inexpensive art medium and a person could “own a masterpiece Ukiyo-e print for about the price of a bowl of noodles.”5 Since his works were geared towards catering to the masses of the public, the prints were primarily intended for Anna Willmann, “Yamato-e Painting”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Last Revised April 2012, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/yama/hd_yama.htm 4 “Ukiyo-E”, Artsy, Accessed November 29th, 2020, https://www.artsy.net/gene/ukiyoe#:~:text=Literally%20meaning%20%E2%80%9CPictures%20of%20the,romantic%20landscapes%2C% 20and%20erotic%20scenes. 5 pleasure inducing.6 The different hues from “Fuji on the Left of Tōkaidō Road” did not carry any symbols or icons. Instead, they were meant to capture the free spirits of Japanese society. Set in a rural Japanese village, Hiroshige’s drawing of Tōkaidō Road also saw a break from traditional Yamatō-e style— which often captured the lives of the famous, the noble or renditions of traditional folklores. Using traditional methods to paint modern subjects, Hiroshige immortalised the bustling imagery around Tokyo for generations to behold. In many Asian paintings, the mood(意境) of the painting is more important than accuracy of the subject. In China, traditional watercolours can leave an entire page of canvas blank for the admirer to imagine. In Hiroshige’s style, the realism is created through careful colour choices and detailed inscriptions. His album of “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” is nothing more than vignettes of 19th century Japanese life. “Fuji on the Left of Tōkaidō” is only a beautiful example from Hiroshige’s series and it is the audience’s duty to piece the fragments together. Whether a person is observing this masterpiece as a contemporary or historian, Hiroshige’s sunset on Tōkaidō Road leaves you with a flow of tranquility. This image have inspired and will continue to enlighten artists for generations to come. 6 Asian Department, “Art of the Pleasure Quarter and the Ukiyo-e Style”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm