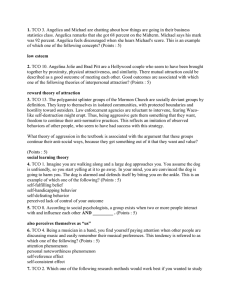

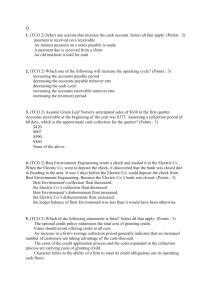

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235292888 Total Cost of Ownership: An Analysis Approach for Purchasing Article in International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management · October 1995 DOI: 10.1108/09600039510099928 CITATIONS READS 372 16,693 1 author: Lisa M. Ellram Miami University 147 PUBLICATIONS 17,019 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: The Future of Supply Chain Finance (SCF) - Financial Flows & Sustainability View project Purchasing ans Supply Performance management and cost savings View project All content following this page was uploaded by Lisa M. Ellram on 30 December 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. IJPDLM 25,8 Total cost of ownership An analysis approach for purchasing 4 Received June 1994 Revised January 1995 Revised May 1995 International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 25 No. 8, 1995, pp. 4-23. © MCB University Press, 0960-0035 Lisa M. Ellram Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona Background Total cost of ownership (TCO) is a purchasing tool and philosophy which is aimed at understanding the true cost of buying a particular good or service from a particular supplier. While there have been references to the TCO approach in the literature for some time[1,2], many firms, particularly in the USA, have been slow to adopt TCO. Total cost of ownership is a complex approach which requires that the buying firm determines which costs it considers most important or significant in the acquisition, possession, use and subsequent disposition of a good or service. In addition to the price paid for the item, TCO may include such elements as order placement, research and qualification of suppliers, transportation, receiving, inspection, rejection, replacement, downtime caused by failure, disposal costs and so on. TCO may be applied to any type of purchase. The cost factors considered may be unique by item or type of purchase[3]. Based on case studies of 11 organizations that are actively using formalized TCO approaches in purchasing, this article explores the answers to the following questions: ● What are the theoretical underpinnings of TCO analysis? ● What are the benefits sought in TCO implementation and what are the barriers which slow down TCO adoption? ● What are the potential uses of TCO models? ● Is there a relationship between the type of TCO model selected and its primary use? ● Are there organizations which use their TCO model for more than one such primary use? Do certain types of TCO model better lend themselves to multiple uses? ● What are the implications of these findings for TCO model development and modification? The author would like to thank the Center for Advanced Purchasing Studies and the Arizona State University College of Business, Alumni Association and Council of 100 for their support in this research. Before proceeding to the case studies, TCO is compared with other supplier selection and evaluation systems. TCO versus other methods of supplier evaluation and selection Traditional approaches to supplier selection and ongoing evaluation include selecting and retaining a supplier based on price alone, or based primarily on price, or qualitatively evaluating the supplier’s performance using categorical or weighted point/matrix approaches[4,5]. While the latter approaches are preferred to a “price only” focus, they tend to de-emphasize the costs associated with all aspects of a supplier’s performance, and generally disregard internal costs. Examination of such costs is a strength of the TCO approach. Selection and evaluation approaches which are closely aligned with TCO include life-cycle costing[2,6], zero-base pricing or all-in-costs[7], cost-based supplier performance evaluation[8], and the cost-ratio method[4,5]. None of these approaches has received significant, widespread support in the literature or in practice for a variety of reasons. Life-cycle costing focuses primarily on capital or fixed assets[2,6]. The emphasis is understanding the purchase price of the asset and also on determining how much it actually costs the organization to use, maintain and dispose of that asset during its lifetime. Pre-transaction costs tend to be deemphasized. The life-cycle approach is congruent with TCO, but represents only a subset of TCO activity. TCO is broader in scope and includes the prepurchase costs associated with a particular supplier. Zero-base pricing[7] and cost-based supplier performance evaluation[8] both advocate understanding suppliers’ total costs. In contrast to TCO, zero-base pricing focuses heavily on understanding the supplier’s pricing structure and the supplier’s cost of doing business. Cost-based supplier performance evaluation has a narrower scope than TCO by focusing primarily on the external costs of doing business with a supplier rather than on both the internal and external costs, as does TCO. Recently, there have been several articles published which focus specifically on the total cost of ownership. Handfield and Pannesi[9] explore understanding total cost of ownership specifically for components, using the product life-cycle approach. They note that TCO components’ issues are directly related to where the component is its life cycle and that the component life cycle may not be related to the overall product life cycle. Carr and Ittner[10] present an overview of total cost of ownership approaches used by several organizations. The models which they present are all modified versions of the cost ratio method. Using the cost ratio method, an organization usually identifies several key factors that increase costs. Factors that increase costs, such as those resulting from poor quality and late delivery, are added to the total purchase price. Dividing these total costs by the total purchase price yields an “index”. This index is then used as a multiple for future bids/prices from the supplier to evaluate the true “total cost of ownership” of doing business with that supplier. Ellram and Siferd[11] developed a conceptual Total cost of ownership 5 IJPDLM 25,8 6 framework for costs to be included in TCO analysis. Ellram used case studies of organizations which have used formal TCO analysis to develop a framework for TCO implementation[3,12]; Ellram[13] also developed a taxonomy for classifying TCO models according to the type of buy, also known as “buy class” (type of purchase), and whether the TCO model is standard or unique. Approaches similar to the total cost of ownership in purchasing have been advocated in the logistics literature[14-17] and strategic management literature[18] as means of understanding total costs throughout the supply chain. Previous work in logistics supply chain costs is conceptual in nature. Such work does highlight the importance of understanding total cost of ownership related to purchasing in developing a realistic cost perspective of the total channel. Thus, TCO concepts can make a significant contribution to understanding total channel costs. Lack of understanding of TCO can be very costly to the firm. Poor decisions will likely result, hurting the firm’s overall competitiveness, profitability, pricing decisions and product mix strategies [3,7,11,12,14-22]. This study extends the previous research by considering the primary motivation for using TCO and relating that to the type of TCO model chosen. This article makes a contribution by analysing actual practices of firms that use a variety of TCO approaches and developing alternative frameworks for TCO. Many previous studies of total cost analysis in both the purchasing and logistics literature have been broad and conceptual[4,5,15,16,23], or limited to one or two case studies[2,6,8]. Theoretical underpinnings for TCO analysis Economists have discussed the importance of going beyond price to encompass transaction cost analysis in purchasing from external sources. Economists tend to focus on asset specificity (the need to invest in specific assets to support certain activities) and the likelihood for opportunistic behaviour to occur. Economists have viewed transaction cost analysis primarily from a make-orbuy perspective[24-26], considering internal production of goods or services versus buying in the market. However, transaction costs are the foundation for TCO analysis as well. While TCO analysis can be applied to the make-or-buy decision, it should also be applied after an organization has determined that it will use a third party (buy) rather than an internal source (make). Transaction costs can vary significantly among suppliers and can be an important decision factor. From this perspective, transaction cost analysis in the economics literature provides the theoretical basis for TCO analysis in the purchasing and logistics literature. Turning to applications of transaction cost analysis in the marketing literature, Heide[27] notes that transaction specific investments may involve human assets that are difficult/costly to replace. In terms of purchasing, this could include suppliers’ employees, such as engineers, account executives and customer service personnel who have specialized knowledge and are dedicated to making the account run smoothly. For example, a supplier’s concurrent engineering and after-sales support may significantly lower the buying organization’s cost of doing business with this supplier versus the free market. In dealing with external uncertainty – which creates an environment conducive to opportunistic behaviour – the marketing literature notes that opportunism is decreased when there is an interpenetration of organizational boundaries[28]. This is relevant to the total cost of ownership of buyer-supplier relationships in that there are costs which should be recognized which are associated with forming such close buyer-supplier relationships. These costs include dedicating assets, such as key account personnel. Likewise, there should be a reduction in transaction costs from creating such close relationships. Examples of this include a reduction in the costs of soliciting and evaluating bids and proposals from numerous suppliers, and searching for and evaluating potential new suppliers. Previous literature on TCO analysis defined transaction costs based on costs that are incurred prior to actual sale; costs associated with the sale, including price; and costs after the sale has occurred, including disposal[3]. Such cost considerations are supported by the marketing literature’s application of transaction cost analysis to specific assets and opportunism. TCO analysis is a valuable tool and philosophy to support the application of the theory of transaction cost analysis to buyer-seller relationships. Barriers to and benefits of TCO The complexity of TCO may limit its widespread adoption. Lack of readily available accounting and costing data in many organizations is a major barrier. This situation has the potential to change as more organizations implement activity-based costing[13,22,29]. However, this change has been very slow in coming. Another complicating factor is that there is no standard approach to TCO analysis. Research and a review of the literature have indicated that TCO models used vary widely by company, and may even vary within companies depending on the buy class and/or item purchased[3,6,7,11,19,21]. Thus, user training and education are probably needed to support TCO efforts. Further, TCO adoption may require a cultural change, away from a price orientation in procurement and towards total cost understanding[3,11]. That potential for cultural change is a major reason why TCO is regarded as a philosophy, rather than as merely a tool. An additional factor which complicates TCO is that TCO costs are often situation-specific. The costs which are significant and relevant to decision making vary on the basis of many factors – such as the nature, magnitude and importance of the buy[13,20]. However, TCO provides many benefits that are documented in the literature[2,7,8,11] and confirmed by case studies[12]. Some of the primary benefits of adopting a TCO approach are that TCO analysis: ● provides a consistent supplier evaluation tool, improving the value of supplier performance comparisons among suppliers and over time; ● helps clarify and define supplier performance expectations both in the firm and for the supplier; Total cost of ownership 7 IJPDLM 25,8 ● ● 8 ● ● ● provides a focus and sets priorities regarding the areas in which supplier performance would be most beneficial (supports continuous improvement), creating major opportunities for cost savings; improves the purchaser’s understanding of supplier performance issues and cost structure; provides excellent data for negotiations; provides an opportunity to justify higher initial prices based on better quality/lower total costs in the long run; provides a long-term purchasing orientation by emphasizing the TCO rather than just price. This list of benefits is by no means comprehensive. It provides a summary of some of the key benefits of adopting a TCO philosophy in purchasing. It is important to note that none of the organizations studied use TCO for all purchases. The use of TCO is reserved for certain items/services where the organization feels that such analysis can provide greatest benefit. Before proceeding with the research results, the next section will discuss the research methodology used. Methodology This research involved case studies of 11 organizations which were actively involved with and used formalized TCO models in purchasing. A formalized model is defined as a written, documented method for determining the total costs associated with the acquisition and subsequent use and disposition of a given item/service from a given supplier. As previously mentioned, much of the current literature on TCO is anecdotal or descriptive in nature[17, 23], or involves only one case study firm[6,8]. Thus, because of the limited amount of data available on TCO models in the literature, this research is exploratory in nature. It seeks to describe and understand TCO analysis in depth, rather than provide a broad but limited picture of TCO practices among a large population of organizations. Interview approach The interview guide used in the research was developed based on the research questions of interest and combined with a review of the relevant literature. Both academics and purchasing practitioners reviewed the interview guide for content and clarity. The interview guide was also pre-tested with one firm. The interview guide was modified based on these inputs. Sample selection Owing to the relatively limited availability of firms which actively use TCO in purchasing, the case study firms in this research are not a random sample. This purposive sample was developed based on the author’s knowledge, a review of the literature and recommendations of purchasing practitioners. Each case study firm was pre-screened over the phone to determine, first, whether it actually used a formalized TCO model, in terms of the above definition, and, second, whether it would be willing to participate in the research as a case study. Case study firms The use of TCO models is widely dispersed across industries, as shown in Table I. The convenience sample includes: two semi-conductor firms and a semi-conductor consortium; one manufacturer of diversified electronics and computer components; one manufacturer of telecommunications systems; one manufacturer of transportation vehicle components; a defence electronics manufacturer; an oil company; a manufacturer of medical systems; a manufacturer of defence aviation products; and a manufacturer from the process industry. While this is clearly not a representative sample, there are two issues to consider. First, high technology companies often lead purchasing innovations due to the importance of supplier performance to their products and the relatively high dollar value of purchased items to the firm. Second, the research did not find a common pattern among TCO models across high-technology companies. Total cost of ownership 9 Potential use of TCO models The potential uses of TCO models are closely related to the benefits of TCO models pointed out above. In general, based on the case study firms, there are a number of uses for TCO model data. However, for each firm, there is one primary use for the data which drives the development of the model. That primary use is based on the impetus for implementingTCO. The two lists which follow show the uses for TCO data identified by the case study firms, followed by the primary reason each case study firm uses TCO. Industry Oil (Shell) Semi-conductor (Intel, Motorola SPS) Semi-conductor consortium (SEMATECH) Telecommunications equipment and support (Northern Telecom) Defence/electronics (Motorola) Diversified electronics/computer (Texas Instruments) OEM manufacturer for transportation industry (Firm W) Medical systems (Firm X) Defence/aviation (Firm Y) Process industry (Firm Z) Number of organizations 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Table I. Industry representation of case studies IJPDLM 25,8 10 Reasons for using TCO These include: (1) support supplier selection/RFP, RFQ, RFB: ● new suppliers; ● choose among existing suppliers; (2) give supplier performance recognition awards; (3) drive supplier improvements, identify priorities; (4) drive major process changes; (5) plan or anticipate future supplier performance; (6) measure ongoing supplier performance; (7) provide data for negotiations; (8) forecast new item performance based on historical data; (9) concentrate resources on important few purchases; (10) compare supplier performance (benchmark) against others and self over time; (11) support strategic alliance efforts; (12) supply base reduction/volume allocation decisions. Primary reasons for TCO adoption These include: ● supplier selection decisions: e.g. Intel, Motorola SPS, SEMATECH, Firm W, Motorola GSTG, Firm Z; ● measure ongoing supplier performance (evaluation): e.g. Texas Instruments, Northern Telecom, Shell; ● drive major process changes: Firm X, Firm Y. Primary use of TCO As indicated, there are three primary uses of TCO model data by the case study firms: supplier selection, supplier evaluation or measurement of ongoing supplier performance, and to drive major process changes/re-engineer. The case study firms lean towards supplier selection as the primary driving force behind TCO adoption. The six firms which use TCO primarily for supplier selection also use TCO data for a variety of other purposes, from driving supplier improvements to negotiating. There is no strong pattern among the secondary data uses for those who cite supplier selection as a primary TCO use. The three organizations which indicate evaluation of ongoing supplier performance as the primary reason for using TCO modelling, also note driving performance improvements and providing data for negotiations as secondary reasons for TCO modelling. Thus, in some sense, these firms were using TCO to support supplier selection decisions. In addition, these organizations use their TCO data for benchmarking supplier performance among suppliers and for looking at supplier performance improvements over time. Another use of data noted by both of the “performance evaluation”-focused firms was in allocating volume among the existing supply base and/or reducing the existing supply base. The two organizations which use TCO primarily to analyse and drive process changes take a very broad, systemic approach to TCO analysis. Rather than focusing on purchasing-related issues and supplier performance only, these organizations used TCO analysis to support broad outsourcing/make/buy decisions that had implications far beyond purchasing. While other organizations use TCO analysis to support strategic and/or make or buy decisions, it was not the driving force. The firms which focused on driving process change do not use TCO for ongoing supplier evaluation, but do use it to support the selection decision. One surprising finding is that only four of the firms – Texas Instruments, Northern Telecom, Shell and Firm Z – use TCO for both supplier selection and ongoing supplier performance evaluation. In other words, firms who use TCO for supplier selection generally do not use TCO for ongoing evaluation of the supply base. Firms who use TCO for ongoing supplier evaluation tend not to use TCO data for supplier selection of new suppliers. This will be discussed in greater depth later in the article. Approaches for determining TCO There are two major approaches to determining TCO used by organizations considered in this research: dollar-based and value-based approaches. Dollar-based approach A dollar-based system is one that relies on gathering or allocating actual cost data for each of the relevant TCO elements. Thus, if a dollar-based model indicated a TCO of, say, US$15.32 for a component, it would be possible to trace the costs of the items that make up that TCO on a cost element by cost element basis. An example of the dollar-based approach to TCO modelling is shown in Figure 1. While determining which cost elements to include and gathering the data to determine the TCO may be complicated, explaining the results of a dollar-based approach is relatively straightforward. There is a variation on the dollar-based approach which uses formulae to allocate actual costs by item purchased by supplier. The formulae are based on the effort or resource level required to support a given activity, much like the practice of activity-based costing. One type of activity clearly related to a particular purchase from a particular supplier is inspection. Thus, such systems determine the cost of inspection and develop a formula for allocating the cost of inspection to purchases based on the effort required to inspect. When parts are inspected, the parts receive an allocation of actual inspection costs for the period during which the inspection occurred. Those parts which do not Total cost of ownership 11 IJPDLM 25,8 Price paid, F.O.B. origin (12.632/unit) $12,000.00 Delivery charge 500.00 Quality: 12 Cost to return defects $100.00 Inspection (in-house) 300.00 Delay costs (downtime) – Rework parts – Rework finished goods 200.00 –––––––––– $600.00 Subtotal quality costs Technology Our engineers at their facility <credit> Their engineers at our facility <credit> Their design change to improve yield $1,500.00 <300.00> –––––––––– –––––––––– $1,200.00 Subtotal technology Support/service Cost of delivery delays Charge for not using EDI ($50.00/order) Subtotal support/service Total costs Figure 1. Dollar-based TCO illustration Units shipped TCO per unit (total costs/units shipped) $104.00 150.00 –––––––––– $254.00 $14,554.00 950 –––––––––– $15.32 –––––––––– require inspection do not receive the inspection allocation. Thus, this approach creates a more accurate picture of the true cost of doing business. This creates a methodology for using the TCO approach for repetitive decisions, rather than creating a new analysis each time or for each commodity. As mentioned above, using activity level to allocate costs is the basis for activity-based costing, also known as ABC. This principle improves matching activities which drive costs with the items that benefit from those activities, and was a key factor in the development of both Texas Instrument’s and Northern Telecom’s total cost systems. A further discussion of ABC is beyond the scope of this article (see[22,29,30]). Value-based approaches A value-based TCO model combines cost/dollar data with other performance data that are often difficult to “dollarize”. These models have a tendency to become rather complex, as qualitative data are transformed to quantitative data. They often require very lengthy explanations of each cost category. An abbreviated illustration of this method is shown in Figure 2. As illustrated in Figure 2, some value-based TCO models do calculate a total cost of ownership. The total cost derived from value-based models is not directly traceable to dollars spent in the past, spent currently or estimated to be spent in the future, as are the dollar-based TCO results. However, the way in which the supplier’s performance is scored within categories and points allocated among categories reflects the buying organization’s estimate of the cost of various performance discrepancies. Organizations which choose a valuebased approach prefer it because, as costs and the organization’s priorities change, the “weighting” of cost factors can be changed accordingly. Valuebased models require a great deal of fine tuning and effort to develop the proper weightings and point allocations so that they reflect the TCO. Like dollar-based TCO analysis, value-based models are derived from historical data and/or Total cost of ownership 13 Total cost of item per dollar purchased = [(100 - score)/100] + 1 Category Quality Delivery Technology Support Maximum points 30 20 30 20 __ 100 Example: Delivery Percentage of “% of line items delivered maximum points allotted on time” (A) (B) 100% 99% 95-98% 90-94% 85-89% 80-84% <80% 100% of maximum 95% 85% 70% 45% 25% 0% Example: Acme's Score Category Quality Delivery Technology Support Total score Score (A x B) 20 19 17 14 9 5 0 Month ending 12/31/92 Points awarded 25 19 30 18 __ 92 Total cost per item per dollar purchase = [(100 - 92)/100] +1 = $1.08 total cost factor Adjusted cost per unit = Price X total cost factor = $10.00 unit X 1.08 = $10.80/unit TCO Figure 2. Value-based TCO illustration IJPDLM 25,8 14 estimates of future costs. Value-based models tend to focus on a small number of major cost issues, generally around three or four. Calculations beyond this point tend to become too complex. Not all of the case study organizations converted their TC analyses into unitary or some other type of cost. Six of the cases specifically used TC analysis data to develop cost per unit data. Three used a dollar-based TC analysis to develop total cost savings from a process change rather than looking at individual product/service costs. Two used a value-based combination of cost and weighting factors to develop a total “score” which, although based on total cost calculations, was not converted into dollar savings. The relative advantages and disadvantages of the TCO approaches are shown in Table II. The primary uses of each type of model by the case studies is shown in Table III. All of the case study organizations acknowledged and discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the approach they had chosen for TCO analysis. Perhaps the major issue in developing a TCO approach was the trade-off between an approach that was easy to use, and one that was complex and flexible enough to capture key issues. The selection of the approach to TCO was made based on a number of factors, including the types of decision the organizations would be using TC modelling to support. In all of the case study organizations, the TC analysis results were used to support decision making rather than flowing to the organizations’ financial statements. Northern Telecom has a goal of using its model for product/service valuation in the future. This is contingent on implementation of an organizationwide approach to activity-based costing and total cost modelling. Model advantages Disadvantages Dollar-based – direct cost Tailor factors considered to decision Very flexible Alter level of complexity to fit decision Help identify critical issues Time consuming Does not make sense for repetitive decisions Not cost beneficial for low dollar buys Dollar-based – formula Easy to use once system is in place Excellent for repetitive decisions where costs for key factors can be determined Table II. Comparison of relative advantages of dollarbased and value-based TCO models Value-based model Can incorporate issues where costs cannot be determined Considers the importance of factors using weighting Easy to use for repetitive decisions Time consuming to establish system Formulae need to be periodically reviewed and updated Inflexible to different types of decisions Considers a limited set of factors Time consuming to develop; only good for important and/or repetitive decisions Much judgement in establishing weightings Type of model Primary uses Dollar-based – direct cost Supplier selection Supply base reduction Make versus buy/outsource Process improvement Dollar-based – formula Supplier volume allocation Supply base reduction Ongoing supplier evaluation Process improvement Value-based Supplier selection Make versus buy/outsource Process improvement Unique versus standard models The organizations studied tended to use unique models that are specially developed for each buy. These models may share a common set of total cost factors, such as quality, delivery and service. But the data need to be separately developed for each buy. Organizations chose to use a unique versus a standard type of model for a number of reasons, as shown: ● Factors which favour a unique model: buys to be considered vary greatly; no one set of factors captures critical issues across buys; desire for flexibility in cost modelling (adapting to user needs, adapting to various buys, adapting to changes in internal focus). ● Factors which favour a standard model: issues of concern are same across buys; desire for user-friendly/relatively easy to use model; desire to computerize the system; desire to analyse repetitive purchases. The key factor which determined the choice between a unique and a standard TCO model was the type of buy to be considered (see Table IV). In instances where an organization desired to analyze repetitive buys, or buys where the same cost factors were of primary concern across buys, a “standard” model was developed. This was the case for Northern Telecom, Texas Instruments and the SEMATECH capital model. The remaining models studied were unique. Some TCO models were developed to support a particular commodity and would be used repetitively for evaluation or selection over the life of that commodity. Other models were developed for a one-time buy or for a long-term decision, and would not be specifically reused. The latter was particularly true in make/buy or outsourcing decisions. Total cost of ownership 15 Table III. Primary uses of various types of models among case studies IJPDLM 25,8 Non-repetitive buys Productive capital 16 Table IV. Determination of whether to use standard or unique models Develop a relatively standard model for capital which can be adapted for other capital purchases Repetitive buys Type of buy Major acquisitions, Supplier selection make-buy or with no or ad hoc process analysis updates Ongoing supplier performance monitoring, perhaps selection Recommended TCO approach Develop a unique Develop a standard model which fits model that can be that buy, and can be used across buys, updated to evaluate manual or actual performance computerized versus estimate Develop a standard computerized model that is automatically updated monthly or quarterly, can be used across buys Comparison of the two TCO approaches Based on previous research[13], the classification of TCO model type by primary model use has been expanded, as shown in Figure 3. The models are further classified as to whether they are standard models (basically the same costs considered for each buy, with a standard format) or unique (a new model developed for each buy) and by type of buy, also known as buy class. All of the organizations that use a TCO model primarily for supplier evaluation also use it to some degree for selection. This figure provides some interesting insights. Two of the firms which use TCO models primarily for evaluation use standard models. This is logical, given that these models will be used repetitively for tracking and reporting supplier performance and communicating performance information to suppliers. The third organization, Shell, has a standardized format it recommends. However, the cost factors considered are unique, based on their relative importance to that purchase. Thus each model is unique. All of the users of standard evaluation models share TCO data with their suppliers. Standardization makes the models easier to maintain. In addition, if the TCO model format and content were changing, the supplier would probably find the model output less useful. Thus, some sort of standardization of evaluation models seems prudent. Further, since Northern Telecom and Texas Instrument’s TCO models are based on ABC principles – which require a great deal of work to set up – it seems wise to standardize them from a resource usage standpoint. Most of the TCO models used primarily for selection are unique. The exception is the model used for production capital. The case study firms use fairly standardized models for production capital because the issues – yield, uptime, maintenance, and so on – are relatively constant across production capital buys. All of these organizations use the standardized SEMATECH capital model or some variation of it. Value-based Primary use Standard Dollar-based Unique Standard Unique Production capital W, Z SEMATECH, TI, SPS, Intel Operating capital W,SPS Intel MRO SPS, Z Intel Components W, GSTG SPS Intel Materials W, SPS Intel Service GSTG, SPS, Z Intel Production capital Shell Operating capital Shell MRO Shell TI Components Shell NT, TI Shell NT, TI S E Total cost of ownership 17 L E C T I O N E V A L U A T I O N Materials Services Process re-engineering SPS Shell Firm X, Y The standard MRO and component models used by Texas Instruments and Northern Telecom were developed as computerized systems. Their models follow the same format for both components and MRO. Model standardization was necessary in order to have the model extract data directly from the firms’ sophisticated computer networks. The models are used for high volume, repetitive buys which have relatively standard TCO elements affecting them. Both Texas Instruments and Northern Telecom developed these models primarily for ongoing supplier evaluation, and currently use them for supplier selection and volume allocation where they have experience with a supplier. The remaining selection-focused models are unique, representing the fact that the case study firms believe that each supplier selection decision is unique. Figure 3. Cross classification of major TCO model use IJPDLM 25,8 18 While building unique models creates more work, it also gives the process more credibility and flexibility to respond to user needs and changing market conditions. Because the users of unique TCO models employ such models only for supplier selection of crucial items, the burden of model creation is not as great as it might otherwise be. Intel is the only one of the six selection-focused firms, excluding SEMATECH, to use dollar-based TCO models. Since it is based on actual costs, dollar-based TCO is relatively easy to explain to other members of the commodity team. The remaining firms use a value-based approach. A possible rationale for this will be discussed in the next section. Organizations which use TCO primarily for process re-engineering use unique models, since each area/process analysed is unique. These organizations also use dollar-based models to reflect their actual past or projected future expenditures. TCO model for selection and evaluation Supplier selection and supplier evaluation are closely related activities. The former relates to choosing the supplier for the right reasons. The latter relates to maintaining a relationship with that supplier over time and helping the supplier identify improvement opportunities as long as it still makes sense to do business with that supplier. This section discusses the finding that using TCO for both selection and evaluation in the same organization appears to be the exception rather than the rule. It further discusses the benefits of integrating supplier-selection and supplier-evaluation models. TCO selection/evaluation modelling in the same firm Only four case study organizations use a total cost of ownership approach for both supplier selection and supplier evaluation. The firms include all three firms that use TCO primarily for ongoing evaluation – TI, NT and Shell – and one firm that uses TCO primarily for selection – Motorola SPS. Shell and Motorola SPS use unique models, while NT and TI use standardized models. Motorola SPS uses a standard TCO model to track ongoing supplier performance and allocate volume among suppliers for one crucial raw material. However, they do not utilize that model in making supplier-selection decisions in the same buy class (raw materials) or other buy classes. This supplierevaluation model is unique to that particular purchased item, while “standard” for that item over time. Thus, although Motorola SPS routinely uses TCO for supplier selection, TCO is used for evaluation only on an exceptional basis. Thus, this firm’s TCO modelling may not be indicative of that of other firms desiring to use TCO for both supplier selection and supplier evaluation. It is interesting to note that Motorola SPS originally implemented TCO for ongoing evaluation of the particular raw material mentioned above. It began with a value-based approach. When it expanded TCO for use in supplier selection, it followed most of the other selection-oriented case study firms in using a unique approach for each buy. It did not, however, switch over to a dollar-based approach like most of the other case study firms. While the number of cases reviewed is too limited to draw conclusions, the type of model with which a firm begins its TCO efforts may have implications when it expands TCO usage. Commonality between selection and evaluation models Both the selection model and the evaluation model provide excellent transaction cost data for reducing the supply base or for allocating volume among suppliers. Indeed, both selection-focused and evaluation-focused firms use their TCO models for this purpose. The evaluation-focused case study firms use TCO data for supplier selection in that they may use such data to allocate volume among suppliers or to reduce the supply base. However, this is quite different from using TCO data to analyse new suppliers. Both selection-focused and evaluation-focused TCO firms also use their TCO data for communicating priorities to suppliers and driving supplier improvements. They use TCO for process re-engineering at a more functional or micro-level than do the two firms which focus on process re-engineering as the driver of TCO. By using TCO at a micro level, they tend to focus on improvements in the purchasing area or at the supplier’s end, rather than on broader, corporate-wide issues. Both sets of firms use TCO data for negotiation purposes, which may be closely related to driving supplier improvements. Thus, there are some definite commonalities between selection- and evaluationfocused TCO approaches. The next section discusses how to give leverage to these synergies. Importance of a TCO model for both selection and evaluation While TCO is a philosophy that involves evaluating suppliers and purchases on a basis beyond price, in execution TCO is a model. TCO models provide a snapshot of supplier performance at a point in time. If historical data are limited or unavailable, as in the case of a potential new supplier, TCO provides data regarding expected performance, based on estimates and externally gathered information. Thus, regardless of whether it is cost based or value based, selection focused or evaluation focused, TCO is an evaluative tool. Using total cost of ownership to select a supplier can be compared to interviewing a prospective employee. The interviewer knows what the organization is seeking in terms of qualifications and what the job duties are. The post should be filled with the best available candidate. Likewise, in performing a TCO analysis for supplier selection, the supplier’s qualifications, in terms of cost elements, are determined. The firm knows how the supplier will be required to perform to meet the firm’s needs. Thus, the best supplier is selected based on the right combination of low TCO and ability to perform additional “duties”, such as special delivery requirements, lead times, and so on. In order to understand and improve on performance, an employee requires feedback. After an employee has been working for an organization for a certain period of time, she or he usually receives a performance appraisal. This gives the employee performance feedback regarding strengths and areas to improve Total cost of ownership 19 IJPDLM 25,8 20 on. An appraisal also verifies whether the hiring decision was a good one. Performance appraisals continue throughout the employee’s career, to ensure that she or he is still doing well and supporting the company’s goals. If the employee is not performing, improvement tactics are implemented, or the relationship is terminated. Likewise, a firm should continue to evaluate suppliers on an ongoing basis. As discussed in the transaction cost analysis literature, the potential for supplier opportunism exists; thus ongoing evaluation of the relationship is required[27]. The firm invested time and effort in choosing the right supplier. Does it not make sense to verify whether the supplier is meeting expectations? Might it not be valuable to give the supplier feedback regarding strengths and areas for improvement? Might it not also be wise to keep the supplier informed of the firm’s goals and expectations, and of how the firm perceives the supplier to be performing against those goals and expectations? How can the supplier be expected to improve without such dialogue? Generally, unless priorities have changed, the supplier should be evaluated based on the same criteria that were considered when the supplier was selected. If that is not the case, the supplier selection model is not looking at the “right things” initially. The two organizations that use unique TCO models for selection and evaluation specifically develop one model that can address both issues. The employer-employee situation can be extended from the standpoint of using TCO for evaluation, but not selection. That is analogous to hiring someone without a proper interview, then hoping that she or he can perform the job duties. Assessment would be made at his or her performance evaluation. If a supplier is selected using a model other than TCO, that is akin to hiring someone based on one set of qualifications, but evaluating his or her performance based on another set. Either way, it does not make good business sense. The selection and evaluation processes are inherently linked. A firm’s own internal hiring processes and supplier management processes should reflect this relationship. Recommendations Based on the results of this study, TCO represents an excellent means to improve supplier selection and evaluation. TCO analysis provides valuable data for improving supplier performance, focusing on and negotiating the cost and performance issues that are of most value to the firm, and monitoring supplier performance over time. As such, TCO represents a valuable tool and philosophy for firms to adopt in understanding supplier-related transaction costs. If competitors in an industry are using such an approach, the organizations not using TCO are at a disadvantage in terms of their supplier and purchased item/service knowledge[12,16]. Neither the dollar-based nor the value-based approach to TCO modelling appears to be superior to the other. Likewise, there is no evidence to support that it is better to use TCO for supplier selection than for evaluation, or process re-engineering or vice versa. In developing and implementing TCO, the best approach is to plan the process, assess what TCO will be used for, and focus on the benefits the firm desires[11]. This is precisely what TI and NT did in developing a TCO approach to support both selection and evaluation. The major weakness of their models is that neither is useful for selecting new suppliers. Two of the major reasons for TCO analysis among the case study firms – supplier selection and supplier evaluation – should work together to benefit the firm. Keeping in mind that TCO modelling is performed on only a limited number of selected items by all of the case study firms, developing a system to focus properly on both selecting and evaluating key suppliers using TCO is not unreasonable. The data derived from these models can be used to support or highlight opportunities for process re-engineering. Whether the firm desires to use a standard or a unique approach for each item will vary with the firm. The researcher recommends that once a model is in place for a particular item, that same model should be used to the greatest extent possible for all supplier selection and evaluation decisions related to that item. This will provide consistency over time for both internal and external communication concerning evaluation and selection. As discussed previously, if process re-engineering is the primary goal of TCO analysis, a unique model is required to reflect the process being analysed. The researcher strongly recommends the use of standardized models whenever they are viable. If the model can be extended to all items in that buy class, or slightly modified without distorting decisions, all the better in terms of work load. However, the integrity of the results should not be sacrificed simply to use an existing model. When a standard model will not fit the situation, an approach recommended by the author, based on Shell and Firm W, is to have a standard listing of major total cost elements common to model builders/users. These can be chosen based on their relevance to the situation and the availability of data. Methods for calculating the costs and/or sources of data should also be made available to simplify the procedures. When considering a new supplier, where internal data are unavailable, one selection-focused firm projects the new supplier’s cost performance on the unknown element to be the same as the worst performing current supplier. The reasons behind this approach are: first, the conservative convention, that it is generally preferred to have a new supplier perform better than expected, rather than worse; and second, there are always costly and unexpected issues with adding a new supplier. A high cost for unknown elements helps cover those issues. Organizations that are currently using TCO only for evaluation and not selection, or for selection and not evaluation, should modify their approach. Combining the benefits of TCO analysis for both supplier selection and supplier evaluation should prove to be a powerful, competitive tool and communication tool. Regardless of the type of supplier selection or evaluation system currently used in a firm, the selection and evaluation systems should be linked, using the same criteria and consistent rating scheme. Total cost of ownership 21 IJPDLM 25,8 22 Using a common model for both supplier selection and evaluation has many benefits. First, the linkage provides focus and a consistent message about what is important to both suppliers and internal users. Second, using a common model will create less work, confusion and training requirements than would different models. Third, the outcome of selection/evaluation can be used directly to pre-qualify suppliers, qualify suppliers, and even be part of the supplier certification process. Thus, all of the firm’s supplier measurement tools will be linked and consistent. Summary and conclusion This article makes a contribution to purchasing and logistics theory and practice in a number of ways, first, by showing the linkage between TCO and understanding total supply chain costs, purchasing costs are highlighted as a crucial element of total supply chain costs. The principles advocated here can be used to understand and evaluate better any link in the supply chain, as well as total supply chain costs. Second, this article establishes a theoretical framework for TCO analysis by linking it to transaction cost analysis in the economic literature. Third, by comparing TCO to other purchasing frameworks, differences are explored, deepening the understanding of the benefits of and barriers to TCO. Third, different TCO methods (cost- and value-based) are compared based on organizations that use TCO. Examples of TCO models are included. The rationale behind using unique versus standardized TCO models is also discussed. As TCO continues to evolve, and more firms implement a TCO approach, research is needed to explore how companies link their supplier-selection and supplier-evaluation models. It would be beneficial to other firms to know if the linked models are generally standard or unique and dollar based or value based. If there is a pattern, can the firms explain their model choices? Further, as firms expand their TCO modelling efforts from selection to include evaluation, or from evaluation to include selection, what issues do they face in modifying current models? Are their new TCO models largely a function of their existing TCO models, or are major changes required? Clearly, there exists a wealth of opportunity for continued research into the use of TCO modelling in purchasing and understanding supply chain costs. References 1. Harriman, N.F., Principles of Scientific Purchasing, 1st ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1928. 2. Jackson, D.W. Jr and Ostrom, L.L., “Life cycle costing in industrial purchasing”, Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vol. 18 No. 4, 1980, pp. 8-12. 3. Ellram, L.M., “Total cost of ownership: elements and implementation”, International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vol. 29 No. 2, 1993, pp. 3-11. 4. Soukup, W., “Supplier selection strategies”, Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vol. 23 No. 2, 1987, pp. 7-12. 5. NAPM, Supplier Performance Evaluation: Three Quantitative Approaches, video from National Association of Purchasing Management, Tempe, AZ, 1991. 6. Fernandez, J.P., “Life-cycle costing”, NAPM Insights, September 1990, p. 6. 7. Burt, D.N., Norquist, W.E. and Anklesaria, J., Zero Base Pricing, Probus, Chicago, IL, 1990. 8. Monckza, R.M. and Trecha, S.J., “Cost-based supplier performance evaluation”, Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vol. 24 No. 1, 1988, pp. 2-7. 9. Handfield, R.B. and Pannesi, R.T., “Managing component life cycles in dynamic technological environments”, International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vol. 30 No. 2, 1994, pp. 19-27. 10. Carr, L.P. and Ittner, C.D., “Measuring the cost of ownership”, Journal of Cost Management, Vol. 6 No. 3, 1992, p. 7. 11. Ellram, L.M. and Siferd, S.P., “Purchasing: the cornerstone of the total cost of ownership concept”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 14 No. 1, 1993, pp. 163-84. 12. Ellram, L.M., Total Cost of Ownership in Purchasing, Center for Advanced Purchasing Studies, Tempe, AZ, 1994. 13. Ellram, L.M., “A taxonomy of total cost of ownership models”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 15 No. 1, 1994, pp. 171-92. 14. Lambert, D.M. and Stock, J.R., Strategic Logistics Management, 3rd ed., Irwin, Homewood, IL, 1993. 15. Tyndall, G.R., “Analyzing the costs and value of the product distribution chain”, Cost Management, Spring 1988, pp. 45-51. 16. Cavinato, J.L., “A total cost/value model for supply chain competitiveness”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 13 No. 2, 1992, pp. 285-301. 17. Porter, A.M., “Tying down total cost”, Purchasing, 21 October 1993, pp. 38-43. 18. Hergert, M. and Morris, D., “Accounting data for management analysis”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 10, 1989, pp. 175-88. 19. Hale, R.L., Kowal, R., Carlton, D. and Sehnert, T., Made in the USA, Tennant, Minneapolis, MN, 1991. 20. Schmenner, R.W., “So you want to lower costs?”, Business Horizons, July-August 1992, pp. 24-8. 21. Henry, J. and Elfant, C., “Cost of ownership”, Purchasing Management, 28 March 1988, pp. 15-20. 22. Kaplan, R.S., “In defense of activity-based cost management”, Management Accounting, November 1992, pp. 58-63. 23. Harrington, L., “Plotting the perfect purchasing program”, Inbound Logistics, June 1993, pp. 23-7. 24. Walker, G., “Strategic sourcing, vertical integration and transaction costs”, Interfaces, May-June 1988, pp. 62-73. 25. Williamson, O.E., The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting, The Free Press, New York, NY, 1985. 26. Coase, R.H., “The nature of the firm”, Economica, Vol. IV, 1937, pp. 386-405. 27. Heide, J.B., “Interorganizational governance in marketing channels”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58 No. 1, 1994, pp. 71-85. 28. Heidi, J.B. and George, J., “Alliances in industrial purchasing: the determinants of joint action in buyer-supplier relationships”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 27 No. 2, 1990, pp. 24-36. 29. Roehm, H.A., Critchfield, M.A. and Castellano, J.F., “Yes, ABC works with purchasing, too”, Journal of Accountancy, November 1992, pp. 58-62. 30. Ellram, L.M., “Activity based costing and total cost of ownership: a critical linkage”, Journal of Cost Management, Vol. 8 No. 4, Winter 1995, p. 22-30. View publication stats Total cost of ownership 23