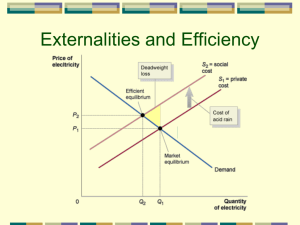

Policy Analysis - PIP 1 Chapter 1 A policy analyst gives professional advice to a client who has certain authority/influence. This is done by a report (see box 1.1) with clearly labeled sections and a brief executive summary where the issue is set and recommendation is done. 2 tasks to understand the policy problem: 1. Diagnose undesirable condition + put into quantitative perspective (comparisons). 2. Framing policy problem as a market/government failure or other circumstance that leads to undesirable outcomes. Market failure = situation in which individual choices do not lead to an efficient allocation of resources. Government failure = situation in which collective action leads to inefficient allocation of resources. In a report you give policy alternatives to the current one to solve these failures. Clarify values by setting out and justifying certain goals. 5 Main goals: efficiency, human dignity, equity, favorable fiscal impact, political feasibility. These goals take into account all the major consequences your alternatives (can) have. Human dignity and equity are distributional concerns, which means policies have impacts on both sides. Common procedure → borrowing and tinkering. You borrow a policy concept and tinker with its details. Alternatives may involve trade-offs among the goals. Chapter 2 Public policy = concerted plans and actions to steer society. - Legal distinction→ governed by public or private law - Economic distinction → funding (tax?) and ownership (government?) - Political distinction → kind of power (collective, pluralistic, individual?) and accountability (to citizens?) 2 Sides: 1. Analytical approach → policy making is rational, cyclical with clear phases. Goal oriented, theory/causal analysis, policy is designed and programmed. 2. Political approach → policy making is constructed, ongoing political battle. Conflict based, analyses are contested and used as weapons, policy results from vectors of power. Different assumptions: - Force of reason and power. - How the (social) world works → manageable, predictable? - Distribution of power → elitism (analytical) vs pluralism (political). Policy analysis = client-oriented advice relevant to public decisions and informed by social values. You have the content (the ´what´) and the process (the ´how´). Content is about the substance and implications of policies, and the last about processes through which policies are adopted. You have clients (individuals and organizations) and epistemic communities (network of professionals). 4 Activities: see table 2.1 1. Policy analysis → the ´what´, clients. Focus on normative aspects. 2. Policy research → the ´what´, epistemic communities. 3. Stakeholder analysis → the ´how´, clients. Focus on instrumental aspects. 4. Policy process research → the ´how´, epistemic communities. Link to political science. Policy research is often for some sort of personal gain, not to influence policy decisions; this limits its direct applicability. They don't write specific and detailed policies like policy analysts, because there is little general/disciplinary interest in this. Policy process research emphasises the relationship between substance of policy and political processes. It looks across political institutions, so focus on the collective effect. Stakeholder analysis is concerned with achieving adoption or implementation of policies rather than the social value outcomes. Policy analysis looks at relevant social values and the policies that promote these values. It tries to give alternatives, predictions, and trade-offs. Responsibility to present all sides. Chapter 3 Ethics in policy analysis → no single value can provide an adequate basis for all public decision making. 3 Important values: 1. Analytical integrity 2. Responsibility to client 3. Adherence to one's personal conception of the good society 3 Roles: see table 3.1 1. Objective technicians → analytical integrity is the fundamental value. Main goal is to give objective advice about consequences. Clients are necessary evils. Trade-offs should be left to the client. 2. Client's advocate → focus on responsibility to the client. Loyalty and confidentiality are important values. You can take advantage of ambiguity in favor of your client's positions. You should select client with the same values or try to change them. 3. Issue advocates → analysis is an instrument for making progress towards their conception of a good society. You should select clients opportunistically, if they don't agree you should leave them. You may take advantage of analytical uncertainty. 3 Common responses to value conflicts: see figure 3.1 → voice, exit, disloyalty. Important → the responsibility to the client against other values (ex: getting fired). Client = highest ranking superior who receives any sort of advice from the analyst. Disloyalty = action that undercuts the political position or policy preferences of the client. Loyalty helps determine how much voice is exercised before exit is chosen. Sub-categories: issue ultimatum (threat of exiting), leak, resign and disclose, speak out until silenced (whistle-blowing). Problem 1: when the client asks analyst to cook up different outcomes. Different reactions: - Objective technician: maybe, if it is likely that the opponent will find it and argument against it. - Client's advocate: maybe, depends on how loyal the analyst is. - Issue advocate: maybe, if they share the same policy preferences. Problem 2: when the client is misrepresenting what the analyst has done (intentionally). Chapter 4 Economic efficiency not as the optimal means/ends ratio, but as degree of achieving welfare optimality. However, it is not the only social value. Utility = perception of your own well-being. The more of any good a person has, the greater that person's utility. Second, there is declining marginal utility. Characteristics of a competitive economy: - Many consumers and (small) producers - Acting as price takers under perfect condition - All maximizing utility and profits (with free entry and exit) - Well defined property rights Pareto efficiency = allocation in which nobody can be made better off without making somebody else worse off. See figure 4.1: - Given is the total endowment and initial allocation. - Actual Pareto frontier (line connecting the agreed points) is relative to initial allocation (status quo point). - Potential Pareto frontier represents all the possible allocations between the 2 persons. - Status quo point indicates how much each person gets in the absence of an agreement. Social surplus = CS plus PS. Maximization of this surplus means Pareto efficiency. Producer/consumer surplus = the difference in what a consumer/producer is willing to pay/produce for and what they actually pay/produce for. Marginal valuation schedule (figure 4.2) indicates how much successive units of a good are valued by consumers in a market. Choke price (Pc) = the price that ´chokes off´ demand. Changes in consumer surplus: welfare assessment of increase in price. Example → tax. Change in CS: tax revenue and deadweight loss (loss in CS). Compensating variation of a price change = the amount by which the consumer's budget would have to be changed so that he/she would have the same utility after the price change as before. Theoretical measure of changes in individual welfare. With a constant utility demand schedule, the CS change is equal to the compensating variation. See figure 4.4. Equivalent variation = how much money you need to give to the consumer if a product X is not available so he/she is as well off as he/she would be with access to a product X. Market demand schedule = summing the amounts demanded by each of the consumers at each price → adding horizontally the demand schedules for all individuals. Pareto efficient equilibrium in perfect competition is characterized by zero profits for all firms. Monopoly rent = difference in profit between monopoly and competitive pricing (figure 4.6). Monopolist → supply is lower than socially optimal: deadweight loss. Producer surplus is the different between TR and TC which is the total rent (figure 4.7). Scarcity rents = excess payments to unique resources. Do not necessarily imply inefficiency. Inefficiencies result from deviations from the competitive equilibrium: marginal value in excess of marginal cost, or marginal cost in excess of marginal benefit (figure 4.8). Chapter 5 Market failure = situation in which decentralized behavior does not lead to Pareto efficiency. 4 common failures: public goods, externalities, natural monopolies, information asymmetries. Private goods: - Rivalrous consumption = what one person consumes cannot be consumed by another. - Excludable ownership = one has control over use of the good. Public goods: - Nonrivalrous consumption = more than one person can derive consumption benefits from some level of supply at the same time. - Nonexcludable in use = it is impractical for one person to maintain exclusive control over its use. Congestion/crowding = if the marginal social cost of consumption exceeds the marginal private cost of consumption. Related to demand; the more, the often there is congestion. Property rights = relationships among people concerning the use of things. De jure property rights are granted by the state but sometimes incomplete (they may be attenuated or superseded). De facto property rights = claims that actually receive compliance from duty bearers. Production of a private good will be in equilibrium at P = MC and MB = MC. The same principle applies to nonrivalrous goods. They should be produced when the sum of all individuals marginal benefits exceeds the marginal cost of producing it (MB = MC). Marginal benefit (MB) of a purely nonrivalrous public good is obtained by vertically summing the demand schedules of all individuals at that output level . → You get the aggregate marginal benefit schedule (figure 5.1). With public goods, there are zero marginal social costs of consumption but positive marginal costs of production at each level of supply. Distinction rivalrous and nonrivalrous: only the sum of valuations can tell how much of the nonrivalrous good should be provided, not the valuations of individuals. Price neither serves as an allocative mechanism nor reveals marginal benefits as it does for a rivalrous good, because once an output level is chosen, every person just consumes it. Public goods market cannot work as a normal market because of freeriding. Figure 5.2! Rivalry, excludability: private goods. Uncongested: efficient market supply and the other way around. Then overconsumption because consumers respond to price. Nonrivalry, excludability: toll goods. Ex: roads that can carry big levels of traffic, or goods that occur naturally like lakes. Exclusion is often economically feasible, so chance of private supplier. Problem: supplier may not efficiently price the good or provide the correct good size/quantity. Uncongested: the social marginal cost of consumption is zero, so any positive price discourages use of the good → underconsumption (figure 5.3). Congested: as additional people use the good, the marginal social costs of consumption become positive (physical capacity constraints). Solution: variable pricing. Nonrivalry, Nonexcludability: pure and ambient public goods. Uncongested: pure public goods (ex: defense). No supply by markets because of the inability of private providers to exclude those who do not pay for them. The larger the number of beneficiaries, the less likely to reveal your preferences. Privileged group: one person makes up a large fraction of total demand so the few persons together are a privileged group (the others can free ride on the one with big demand). Intermediate group: the group is so small, some provision of the good may result because members can negotiate directly with each other. Free-rider problem exists in the large-numbers case because it is impossible to get persons to reveal their true demand schedules for the good. Congested: ambient public goods with consumption externalities (ex: air). Very few goods, because as congestion sets in, you will get exclusion. Rivalry, nonexcludability: open access, common property and free goods. Open access = unrestricted entry of new users. Open effort = fixed number of users may share collective property rights to the good. Here no market failure, because incentive to do good and supply exceeds demand at zero price. Uncongested: free goods. Anyone can take them without interfering with anyone else´s use. Congested: open-access resource = no excess supply at zero price; demand is higher. Common property ownership when entry is restricted and the users own the good in common. Common property resource problem: rational behavior in the group may lead to inefficiency that may end up being indistinguishable from open access. Difference open access and common property ownership: possibility of self-governance. Open access problem: nonexcludability leads to overconsumption of rivalrous goods and underinvestment in preserving the stock of goods. Often with natural resources. Figure 5.5: loss in social surplus because of overconsumption when MSB = ASC = MPC. Nash equilibrium = two-person game where, given the strategy of the other player, neither player wishes to change strategies. Natural resources have the potential for scarcity rents, but these are dissipated with open access or open effort. 2 types of problems with open access and common property: structural (aspects of the good itself) and institutional (property rights). Spatial stationarity = when ownership of resources can be attached to the ownership of land (ex: trees). When goods are not spatial stationary, private ownership/exclusion is hard. Externality = any valued impact resulting from any action that affects someone who did not fully consent to it through participation in voluntary exchange. See table 5.1. Externality problem = situation in which the good conveying the valued impact on non-consenting parties is the by-product of production/consumption of some good. Network externalities = positive externality that arises when a person connects to a Web-based good like digital music exchange. MPC indicates the marginal costs borne by the firms, but does not reflect the negative impacts; MSC indicates total social marginal costs (see figure 5.7). For efficiency, MSC = D (demand), but firms only consider MPC resulting in overproduction. With positive externalities, you have marginal private benefits (MPB), and social marginal benefit (MSB), which includes both private and external marginal benefits (see figure 5.8). Natural monopoly = when average cost declines over the relevant rage of demand. Example: electricity, certain railways → require big infrastructures (figure 5.9). Price elasticity of demand measures how responsive consumers are to price changes. A good is unlikely to have inelastic demand when there are close substitutes, so then there is (often) no natural monopoly. However, forcing the monopolist to price efficiently drives it out of business. Average cost pricing represents a compromise to the natural monopoly dilemma. Natural monopoly firm forced to price at average cost because entry to, and exit from the industry is relatively easy, so threat of competition arises. Contestable markets = market with low barriers to entry and decreasing average costs, so pricing is closer to the efficient level. Competition is possible when the demand curve intersects the average cost curve at the flat part (figure 5.10). Different problems → sectoral (economic boundaries do not conform sectoral boundaries) and spatial (over what spatial area does the natural monopoly exist?). Social cost may be higher because they do not have the incentive to produce at min. cost. X-inefficiency = situation in which a monopoly does not achieve the minimum costs that are technically feasible (figure 5.11). Market failure: undersupply. Information asymmetry = between buyer and seller, when both have different information about a product. Result: over/underconsumption when the producer does not supply the amount of information that maximizes the difference between the reduction in deadweight loss and the cost of providing that information (see figure 5.12). 3 Categories of goods: 1. Search goods = consumers can determine its characteristics with certainty prior to purchase (ex: a chair in stock in a store). 2. Experience goods = consumers can determine its characteristics only after purchase (ex: meals, concerts). 3. Post-experience goods = it is difficult for consumers to determine quality even after they have begun consumption (ex: medicine). Effectiveness of information gathering depends on the variance in the quality and the frequency with which consumers make purchases. The cost of searching for candidate purchases + full price determine benefits of info search. Full price = purchase price + expected loss/damage collateral with consumption. Search goods A consumer pays a searching cost to see a combination of price and quality. When this price is high, the consumer will take smaller samples → information asymmetry. Samples will eliminate this asymmetry if the price and quality combinations are highly homogeneous. Frequent purchasers become experienced so that the searching costs begin to fall. Reputation can also play a big role, like in electronic commerce markets. Intervention in markets for search goods can rarely be justified on efficiency grounds. Experience goods: primary markets To sample, a consumer bears search costs and the full price. Smaller samples for more expensive experience goods. The more heterogeneous the quality of an experience good, the more inefficiency due to information asymmetry. If the quality is heterogenous/unstable, learning proceeds slowly. When consumers perceive that sellers do not have a stake in maintaining a good reputation, and marginal cost of supply rises with quality, only sellers of lower-than-average-quality goods can make profit and survive in the market. Solution: warranties. Experience goods: the role of secondary markets Private third parties can help remedy information asymmetry problems: - Agents → sell advice about the qualities of expensive, heterogeneous, infrequently purchased goods. - Loss control by insurers → send warnings through premium or direct information. - Certification services → ´guarantee´ minimum quality standards in products. - Subscription services → pay for published information about products (free rider problem) Inefficiency when: quality is heterogenous, branding is ineffective, and agents are too expensive/unavailable + distribution of quality unstable so consumers/agents learn slower. Post-experience goods Post-experience goods involve uncertainty, and frequent purchases are not effective in elimination information asymmetry. Secondary markets have a role, but less effective due to learning problems. Chapter 6 Other limitations to the competitive framework: Thin markets - Thin market = markets with few sellers or few buyers - Assumption: consumers take prices as given (behave competitively). - Imperfect competition → Pareto inefficient allocations. - Monopsony = single buyer can influence price by choosing purchase levels. - Oligopoly = 2 or more firms account for a significant fraction of output. Inefficient through cartelization or cutthroat competition → antitrust policies. Preference problems - Assumption: each person has a fixed utility function. - Endogenous preferences: economic inefficiency because advertising or addictive goods changes preferences. - Solution: policies that address addiction and reduce the costs of self-control. - Other-regarding preferences: we care about the consumption of at least some others, not all our preferences are self-regarding. When decreasing goods for 1 person and nothing happens to the rest (Pareto efficient) this may not be Pareto improving, if you care about relative consumption positions. - Process-regarding preferences: we care about how the distributions are produced. - Assumption: all preferences are legitimate, but we see some preferences as illegitimate when it has negative external effects and violates human dignity. Problem of uncertainty - Assumption: efficient markets exist for all goods under all contingencies. - Availability of insurance: actuarially fair when the premium exactly equals the payout, so each person´s utility remains constant → do not exist in real life: administrative costs + you must know the probabilities of the covered contingencies + risk premium (reflects lack of confidence in the estimates of probabilities). - Adverse selection, moral hazard, underinsuring: With adverse selection, those with higher-than-average probabilities will have insurance, which drives up insurance prices above the actuarially fair level. Moral hazard = reduced incentive that insurees have to prevent compensable losses - Assumption: people make rational decisions in situations involving risk. Expected utility hypothesis = people choose to maximize the probability-weighted sum of utilities under each of the possible contingencies. - Prospect theory: endowment effect + loss aversion (behavioral economics). Intertemporal allocation - Assumption: forward markets exist for all goods. Demand for borrowing must be equal to the supply of loans, resulting price is interest rate → not in real life. Problem: moral hazard, capital markets are imperfect. - Shift of costs and burdens between generations. - Underinvestment argument: no collective decision about how much to save for future generations will be any better than allocations made by private markets. Problem: unique goods + capital depreciates over time (but knowledge does not). - Option demand = willingness of nonusers to contribute to maintenance of resource for own possible use in the future. Existence value = willingness to pay for preservation of resource for use by future generations or for its own intrinsic worth. Adjustment costs - Assumption: perfect market is static and can move costlessly from one equilibrium to another → not in real life: slowly changing markets with sticky prices (ex: wages). Consequence: under/unemployment Macroeconomic dynamics - Economy goes through cycles of expansion and recession. Fiscal policy involves taxation and expenditures. Monetary policy refers to manipulation of the money supply (interest rates). Table 6.1! Chapter 7 Social welfare function aggregates the utilities of the individual members of society into an index of social utility. Efficiency is defined as the allocation of goods that maximizes the social welfare function. 3 Social welfare functions (table 7.1) 1. Utilitarianism (consequentialist theory) → goal: maximize average utility. Everybody´s utility counts (democratic), but weak protection of individual rights. Actions are to be evaluated in terms of preferences for various consequences. Sum up the utility of the people: U1 + U2 + U3. 2. Rawlsianism → veil of ignorance, original position to make a social contract, because people agree to institutions behind the veil of ignorance. Equal liberties + maximin principle. Criticism: extreme redistribution reduces incentives to create wealth + in practice it would turn out differently. 3. Multiplicative → maximize average utility with some floor constraint. Multiply the utility of the people: U1 x U2 x U3. Problems with social welfare functions (SWF) 1. Envy → principle of no envy = a social allocation is equitable if no one would prefer anyone else´s personal allocation to their own. Problem: utility is a subjective concept that defies direct measurement. ´Solution´: relating social welfare to the consumption that produces utility for the members of society. 2. No vote/choice for SWF → the SWF must somehow be specified, but no fair voting procedure can guarantee a stable outcome. Ultimatum game = proposer offers a division of a fixed sum of money to a responder, who can either accept or reject it. If accepted, both receive it, but if rejected, both receive nothing → people dislike being treated unfairly. Dictator game = proposer can dictate the allocation because the responder cannot refuse it → proposer offers less than before, but still some 20/30 percent. 3. Limitations in information and cognition → to make the application of the SWF more tractable, it is necessary to divide society into groups. Problem: risk of obscuring important differences among individuals within groups. 4. Longer-term consequences often unknown → now SWF only depends on immediate consequences to keep the burden of prediction manageable. Act-utilitarianism = rightness of an act depends on the utility that it produces. Rule-utilitarianism = rightness of an act depends on its adherence to general rules/principles that advance social utility → focus on institutions encourages a broader and less myopic perspective. Human dignity: equity of opportunity and floors on consumption All people have intrinsic value, need to respect the dignity of others → we should have the freedom to choose how you live. Pareto-efficient allocation involves the premature death of some people because you need endowments to participate in the market process. Most people have the potential to sell their own labor → policies for education, job training and anti-discrimination by employers. But some don't → direct public provision of money. Public policies are not only desirable for greater efficiency, but for respect of inherent values. Increasing the equality of outcomes Vertical equity = those with greater wealth should pay higher taxes so that everyone gives up the same amount of utility. There should be a minimum level of consumption to ensure commonly recognized needs to survive → this level can change as wealth in society as a whole changes. If everyone received the same share of wealth, incentives to work hard would be reduced. Imbalance between wages and executive compensation arises because of a weaker position in wage bargaining and diffuse ownership of stocks. Preserving institutional values Constitutions = definition of the rights/duties of those who reside within their boundaries, and the procedures their officials must follow in the creation and enforcement of laws. Social values: keep public policy within the bounds of the constitution + protecting constitutions from threats external to policy. Voluntary compliance reduces costs + enhances legitimacy → perception of fairness. Cautions in interpreting distributional consequences: - Measurement issues: not all wealth is fully reflected in measured income + tax and transfer programs alter the amount of available disposable income + individuals usually consume as members of households. - Index issues: no single index can fully summarize a distribution. Commonly used is the Gini index of relative inequality (related to the Lorenz curve, see figure 7.1). - Categorization issues: groups almost always differ in important ways other than their defining characteristics (ex: households (whites and nonwhites) → other factors?) - Silent losers issues → silent losers = those who fail to voice protest against the policies causing their losses. Reasons: they unexpectedly suffer losses as individuals + they do not connect their losses to the policy + they are not yet born. Instrumental values = things we desire not for their own sake but because they allow us to obtain policies that promote substantive values. The distributional consequences of policies are of fundamental concern for political feasibility → support for policies favored by their constituencies, which leads to distributional considerations not corresponding to substantive values. Revenues and expenditures important → raising public revenue is costly + expenditure levels serve as the level of effort government is making to solve social problems. Chapter 8 Government failures → see table 8.3! Problems of direct democracy - Paradox of voting: no method of voting is both fair and coherent. Problem gets more complicated because of opportunistic/sophisticated voting in which people try to avoid their least preferred alternative. General possibility theorem → axioms of fairness: - unrestricted domain (transitivity), Pareto choice (unanimous preference), independence, non-dictatorship. - Any fair rule for choice will fail to ensure a transitive social ordering of policy alternatives. Those who control the agenda can manipulate the social choice (figure 8.1). Persistent losers will introduce new issues to create voting cycles and defeat dominant coalitions because of periods of disequilibrium. - Preference intensity and bundling: voting only by referendum can be Pareto inefficient and distributionally inequitable (ex: express highway). Also, not everyone votes according to strictly private interests. Tyranny of the majority = majority inflicts high costs on a minority. Voting does not allow people to express the intensity of their preferences. Having to vote for a bundle of policies can also be Pareto inefficient (ex: candidate with minority position can still win). - Democracy as a check on power: advantages → encourages citizens to learn about public affairs + it provides a check on the abuse of power: intrinsic social value. Problems of representative democracy Representative as a trustee (accordance with constituency´s interest) and as a delegate (accordance with desires of a majority of constituency) → can bring dilemma´s. Influence on behavior of representatives: 1. Own private interests → want re-election (only focus on constituency + vote buying). 2. Individuals make costs to monitor behavior of representatives → interest groups more influence. 3. Party discipline may constrain self-interested behavior of representatives. - Rent seeking = lobbying for interventions that create economic benefits in the form of rents (ex: use government to restrict competition through licensing, tariffs/quotas). No political activity of individuals if the costs exceed the expected benefits. 4 Categories of political competition: interest group politics (costs and benefits concentrated), entrepreneurial politics (benefits diffused, costs concentrated), client politics (benefits concentrated, costs diffused), majoritarian politics (both diffused). Sometimes governments generate rents by directly setting prices (figure 8.2). Transitional gains trap = due to a price floor, price of land rises. Farmers will sell land and capture all rents, while the buyers will have debt. Supply curves shifts up, but elimination of supports will force owners into bankruptcy. Both concentrated and diffuse interests can become politically effective (lobbying). 3 Factors success diffuse interests: attention to issue from large segment of electorate, low public rust in concentrated, policy entrepreneurs willing to promote. → Can facilitate rent seeking (price ceilings), see figure 8.3: need rationing scheme. - Problems of geographic representation: legislators rely on voting to reach collective decisions + represent constituencies with heterogeneous preferences. Problem 2: efforts of representatives to serve the narrow interests of their constituencies (self-interest in terms of re-election, so not for national welfare). Problem 3: certain social costs sometimes appear as benefits to districts. Problem 4: pork barrel politics with logrolling = collection of projects that provide sufficient locally perceived benefits to gain adoption of the packages as a whole. - Electoral cycles: self-interest creates incentives to discount costs/benefits that will not occur in the short run + emphasize instant benefits + de-emphasize future costs. Factors: representatives´ perception of their re-election chances + ease with which an opponent can draw attention to the yet-unrealized future costs. - Posturing to public attention: candidates must compete for the attention of the electorate → mass media important, so they need money for political advertising. Problems: makes it harder for challengers to compete, soft-money contributions, independent spending that indirectly supports/attacks candidates. Media-driven policy agenda discourages the careful evaluation of alternatives, because if they wait too long the policy window may close. Reputation is important: sunk costs are viewed differently than economically logical. Other ´problems´: using precedents incorrectly + posturing + use of rhetoric. Problems of bureaucratic supply - Agency loss: contracting involves costs, less-costly is negotiating fairly general labor contracts → hierarchical firms. Principal-agent problem = employers and employees do not have exactly the same interests + costly for employers to monitor the behavior of their employees (agency loss)→ agents have more information about their own activities than their principals. Information asymmetry: discretionary budget = difference between the budget the agency receives and the minimum cost of producing that what will satisfy its sponsor. Executives that cannot/will not return this budget will find ways to spend it anyhow to make their job/life easier, etc.: slack maximization - Necessity to impute the value of output: most public agencies do not sell their output competitively, so representatives have to impute values on goods like national security → difficult to determine optimal size of public agencies. Harder for public agencies because they are expected to act in accordance with principles like equity. - Limited competition: public agencies do not face direct competition, so no incentive to operate efficiently → X-inefficiency (see chapter 5). No dynamic efficiency, weak incentives for innovation. No threats to firm survival + no profit making makes them less innovative as in the market. When there is innovation, no direct competitors to imitate, they cannot lend money from banks, restrictive rules. - Inflexibility because of Civil Service protections: ex ante controls that directly restrict the discretion of agency heads in how they use their resources. Fixed pay schedules under-reward the most productive and over-reward the least productive → former will leave for higher-paying jobs in the private sector. Difficulty to hire/fire employees → reduces ability to implement new programs quickly. Shielding from political interferences makes them unresponsive to the public. - Intra-organizational market failure: public good is non-rivalrous or non-excludable. Organizational public goods problems are like a manifestation of agency costs. Difficulty in assessing these costs is because the hierarchical structure. Inability of the executive to match individual rewards to organizational contributions. Profit sharing prohibited + strict line-item budgets prevent the moving of funds across categories → no effective internal transfer prices. Organizational externalities: public organizations can use resources without paying their full marginal social costs + responsibility for large external costs can be avoided. Civil service protections make it difficult to impose penalties on those responsible. Sometimes undersupply of services that have positive externalities. Problems of decentralization Advantages: system of check and balances + brings citizens closer to public decisions + permits citizens to exercise ´exit´. - Implementation problem: decentralization can hinder implementation of policies. Implementation describes the efforts made to execute the means. The greater the potential for people to withhold their necessary contributions, the - greater the possibility of failure. Many officials have the capability to withhold elements needed for implementation → bargaining power. Central governments must rely on lower levels of government to act, and becomes more difficult when central government has no authority to coerce. Flypaper effect = money intended for local use captured by state agencies handling the grants. Also problem when cooperation among organizations with different responsibilities is required for solving problems. Fiscal externalities: decentralization allows for fiscal externalities to occur in association with the supply of local public goods. The greater the variation in public goods across jurisdictions, the greater the opportunity to exercise choice by moving. Jurisdictions have an incentive to discourage some migrants and encourage others. Immigrants with below-average tax and above-average demands on public services impart a negative fiscal externality to established residents. Jurisdictions often inflict fiscal externalities on each other in competition for industry. Chapter 9 Market failures like information asymmetry and platform intermediation may create barriers to entry the market that allow established firms to reap rents. Regulated firms have a direct and strong interest in preserving such rules to protect their rents → lobbying. Figure 9.1: steps for linking market/government failure to policy interventions. Operational market = if prices legally exist as signaling mechanism (no matter how extensively regulated). If prices are not legally permitted (only black market), assume that market is not operational. Passive government failure = the failure of government to intervene. Non-operational market: if it could operate without serious flaws, you can assume that significant efficiency losses are associated with the existing government intervention. If intervention appears inappropriate, you can assume that both market failure and government failure are relevant → explain why it is failing and search for alternatives. If it is not possible to find changes in current policy that could increase efficiency, the current policy is at least efficient → question is whether other values are at stake. Chapter 10 Generic policies = types of actions that government can take to deal with perceived policy problems. Factors: 1. Rules and regulation 2. Incentives (taxes and subsidies) 3. Information 5 General categories of generic policies: markets, tax and subsidies, rules, non-markets, insurance and cushions. Market mechanisms (see table 10.1) Markets provide the yardsticks against which to measure the efficiency of government interventions. 1. Freeing markets: when there is no inherent market failure. - Deregulation → government failures are legislators responding to rent seeking, distributional concerns, changes in technology or patterns of demand. Removal of formal entry barriers but regulatory oversight. Problems: large distributional/windfall gains/losses + bankruptcies (ex: banks that are ´too big to fail´ and take on too much risk) + disadvantage for stakeholders. - Legalization → freeing a market by removing criminal sanctions. Changing social attitudes (ex: legalizing prostitution). Decriminalization = criminal penalties replaced by civil penalties (ex: fines). - Privatization → denationalization (selling of state-owned enterprises to private sector). Problem: restrictions put on competitors of the newly privatized firm. Demonopolization (relax/eliminate restrictions that prevent private firms from competing with government). Advantages of privatization: efficiency gains, innovation 2. Facilitating markets → allocating existing goods + creation of new goods. As demand increases, a free good can shift into an inefficient open-access situation if good property rights are not established. Problems: established firm that enjoyed use at below-efficient prices will oppose + from a distributional point of view it matters who gets a property rights (lobbying). Intermediation + a platform are solutions. Create new goods known as tradable permits = rights to access resources or discharge pollutants. Problems: thin markets + inferior to straightforward taxes. 3. Simulating markets → the right to provide the good can be sold through an auction. Happens with goods with natural monopoly characteristics (ex: cable television). Problem: winning bidder has both an incentive/opportunity to cheat by reducing quality of the good. Often used in the allocation of rights for the exploitation publicly owned natural resources (scarcity rents). Problem: bidders can collude to limit price. Taxes and subsidies (see table 10.2) Market-compatible forms of direct government intervention. Difference in incentives and rules. They change incentives by altering the relative prices of goods. 1. Supply-side taxes → output taxes and tariffs. Pigovian tax = a per unit tax can lead to an efficient internalization of a negative externality → allows firms to choose how much to reduce production to limit tax. Problem: government needs to know the shapes of social cost/benefit schedules + frequent adjustment of tax rates required. Also use of tax to capture rents. Tariff = tax on imported, and occasionally exported, goods. Justification: infant industry argument, monopsony effects (dominant country can affect world price). 2. Demand-side taxes → commodity taxes and user fees. Commodity taxes internalize the impact of goods with negative externalities. Used to dampen demand of demerit goods, but also revenue generation. User fees help to internalize externalities + price public goods appropriately. Problems: second-best pricing problem, MC pricing may involve prices that do not cover the costs of service provision (need for subsidies/two-part tariff), political feasibility, transaction costs too high 3. Supply-side subsidies → to increase the supply of goods, use of matching grants and tax expenditures. Grants are intergovernmental subsidies. Matching grants when it matches local expenditures as some fixed percentage. (figure 10.1) Decategorization when some of the subsidy spills over to other goods. Solution: maintenance-of-effort requirement = only units beyond a certain quantity are subsidized. Subsidies have to be paid for with other taxes. When negative externalities are reduced through subsidies, consumers bear a smaller burden than with taxation. Problem: opportunistic behavior. Tax expenditures change relative prices by making certain factor inputs less expensive. Research and development (R&D) assistance by governments. Exclusion of competitors impossible, underinvestment of private firms in R&D + when exclusion is possible, firms restrict the information of R&D to suboptimal levels + risky 4. Demand-side subsidies → increase consumption of goods by reducing price. - In-kind grants subsidize the consumption of specific goods (figure 10.2). Subsidize works better than cash if the good generates positive externalities + in the presence of utility interdependence. - Vouchers allow consumers to purchase marketed goods at reduced prices. Vouchers are used for subsidizing a wide range of goods, stimulate market demand. Problem: short-run supply inelasticities (ex: rise of price with housing). Educational vouchers permit public financing and competitive supply. Problem: information asymmetry → vouchers cannot be used without direct regulation of quality. - Tax expenditures stimulate demand for housing, education, medical care and childcare. Lower the after-tax price of the good. Problems: rent seeking encouraged, inequitable distributional consequences. Rules Government uses rules to coerce certain behaviors. There is no such thing as the unregulated economy. 1. Frameworks → civil laws, criminal laws. Establishment of property rights, including rights to health and safety: tort law. Problem: information asymmetry (post-experience goods) + transaction costs. Reduce consequences info asymmetry → contract law (ex: insurance law). Antitrust law prevents firms from realizing rents through cartelization. Enforcement via prosecution under criminal laws by government agency or creation of incentives (ex: multiple damages). 2. Regulations → seek to alter choices that people would otherwise make in markets. Command and control: directives are given, compliance is monitored, noncompliance punished. Can be costly. - Price regulation → prevent monopolies from charging rent-maximizing prices with rate-of-return regulation. Criticism: regulators are ´captured´ by firms that they are supposed to be regulating + inefficient and wasteful behavior. Price cap regulation: regulatory agency sets an allowed price for a specified time period. There is a ceiling but no floor. Often with removal of entry barriers. More dynamic efficiency, investors in the firm need to carry the risk of profit variability. - Quantity regulation → desirable in situations where the cost of error is great because of certainty of outcome. Appropriate when marginal benefit curve is steep, and marginal costs are constant. Quotas transfer rent to foreign producers. The design of efficient standards requires that noncompliance be taken into account. - Direct information provision → to tackle information asymmetry, require the provision of info (but: government or suppliers?). Ex: warning labels on cigarettes. Also: whistleblower protection, organizational report cards, quality standards (limited by lack of expertise in determining the standards + political environments that undervalue some errors). Good policy when there are pure information asymmetry problems, because MC of providing info and enforcing compliance is low. Problem: regulatory capture (rent seeking, reducing competition). - Indirect information provision → direct information cannot always be provided as service quality is not fixed. Solution: register, license, certify certain providers. Licensure different than registration (just a simple declaration) and certification (exclusive rights but not to practice). Problem licensure: monopoly pricing + social costs of entry barriers. - Choice architecture (nudging) → behavioral economics. Encouraging self-beneficial choices by changing circumstances (advance social policy goals). Problems: non-normative ethics takes over + choice architecture is increasingly coercive + paternalism (it's in your own interest) + positive liberty under pressure. Non-market provision Why government provision and not just intervention? (ex: defense). Double market-failure test = there is a market failure + generic policy is not effective. 1. Direct supply → bureaus (ex: national defense). Vague seperation of government bureaus and government corporations. Some generic policies inevitably involve some direct government provision (ex: vouchers). 2. Independent agencies → government corporations and special districts. Government corporations operate with their own source of revenue that gives them some independence from legislative/executive interference. They meet the single market-failure test → need for government intervention. Problem: principle-agent. Without effective governance institutions, corporation not superior to the bureau. Special districts created to supply goods that are believed to have natural monopoly, public goods, or externality characteristics (ex: schooling). Can internalize externalities that spill across boundaries of local governments. Collections of special districts prevent logrolling across issue areas. 3. Contracting out → government goes to private firms or to non-profits (ex: rest facilities in government buildings, sometimes part of the national defense). Problem: new, more complex contract-monitoring for governments. Government can delegate responsibility for the development of rules to stakeholder organizations when it is difficult for an agency to maintain the expertise for good info. Insurance and cushions 1. Insurance → to reduce individual risk through the pooling of risks borne by a group. Reduce moral hazard by investing in monitoring systems + payment structures. Mandatory insurance: adverse selection may limit the availability of insurance, solution is making it mandatory. Losses suffered by those left uncovered involve negative externalities + paternalism (it will combine actuarially based risk pooling with income transfers) + privatize regulation (minimum levels of liability insurance). Subsidized insurance: government often forces private insurers to write subsidized policies in proportion to their total premiums (assigned risk pools). Fairness. 2. Cushions → to reduce the variance in outcomes through a centralized mechanism. With insurance ex ante preparations, with cushions ex post compensation. Stockpiling: insurance for supply disruptions or price shocks for goods without close substitutes that are central to economic activity (ex: oil). Accumulation of quantities during normal periods so that they can be released during periods of disruption. Releasing the goods can dampen the price rise and reduce economic losses. Also used to help support prices (ex: agriculture) + stockpile financial resources. Problems: rent seeking + inequity in availability. Transitional assistance: compensation when projects increase welfare but impose disproportionate costs on individuals → buy-out (government purchases a give benefit) and grandfather clause (allows current right holders to retain their benefits that will not be available in new rights holders in the future). Cash grants: do not interfere with the consumption choices of a target population. (ex: universal basic income). Problems: dependency + reduction in work effort. Table 10.6! Chapter 11 Adoption phase begins with the formulation of a policy proposal and ends with its formal acceptance (ex: law). Formal models of strategic behavior usually take the form of games than unfold through a series of moves by players. Political feasibility important. Table 11.1! Players of the game 1. Interest group theory → concentrated/organized interests advantage over diffused. Analysts wishing to advance policies that favor diffuse interests should mobilize organizations that represent those interests. Try to identify those who would bear diffuse costs from policies if they were adopted → mobilize for repeal of policy. 2. Advocacy coalition framework (ACF) → public policy occurs within policy subsystems (ex: health care). Importance of external events + shocks. Coalitions share deep core beliefs about values + core policy beliefs span the issues within the policy subsystem. Secondary policy beliefs concern specific issues/locales. The 3rd is more amenable to change than the second, second more than the 1st. Lessons: evidence/interventions can change beliefs + exploit shocks that change resources and create a policy window + encourage negotiation in presence of hurting stalemates. Rules of the game 1. Institutional rational choice → strategic behavior within a set of rules. Three levels of rules: operational level ((in)formal), collective choice level (formulated by legislative and executive authorities), constitutional level (rules about collective choice). Provides starting point for framing policy problems and thinking about changes/alternatives. Interrelationship among the levels! Opponents of operational rules will bypass them by changing rules at other levels. 2. Path (State) dependence → ex: QWERTY. Policy feedback makes political processes dependent upon previous policy adoptions. Path dependence when the sequence of policy outcomes/opportunities affect political feasibility of future policy alternatives. State dependence when only current policies affect feasibility. How: increasing returns to scale + policy that affects distribution of cost/benefits of future policies. Three lessons: learn the relevant policy history + beware of quick fixes & radical proposals that are likely to fail + policies create new constituencies. 3. Social construction framework → Four target groups: advantaged (political power, benefits) + dependents (positive social constructions but weak political power, benefits small) + contenders (negative social constructions but political power, both) + deviants (negative social construction and weak political power, burdens). Pay attention to framing (who is your target?), storylines + socialization, identity (´this is who we are´). Mobilize support when constructions are not universal. Course of the game 1. Multiple streams framework → Kingdon´s model: when the lines (problem stream, policy stream, politics stream) intersect there is a policy window. Assumption: problems and solutions are independent. Policy entrepreneurs can bring the streams together. Develop policy alternatives that are ready when a policy window opens. 2. Punctuated equilibrium theorem → process of general stability interrupted by large changes → long-term equilibria with sudden ruptures. Policy stay stable over a long time, but stability can be disturbed (ex: crisis, policy breakthrough). Assessing and influencing political feasibility - Identifying the relevant actors → 2 sets: individuals and organized groups with interest in the issue + those with official standing in the decision arena. Assume that anyone with a strong interest will become an actor. - Understanding the motivations and beliefs of actors → often apparent, if not then look at costs and benefits. Multiple motivations for elected officials, political appointees and civil servants → where you stand depends on where you sit. - Assessing the resources of actors → based on positions and relationships. - Choosing the arena → each arena has its own set of rules about how decisions are made. You can dodge certain disadvantages by moving the issue to another arena. Legislators and executive branches will try to shift the arena to the courts. Political strategies within arenas - Co-optation → getting others to believe that your proposal is partly their idea: co-opt potential opponents, they will see you less as a threat. Use when your proposal infringes on the turf of other political actors. - Compromise → substantive modifications of policy proposals intended to make them more politically acceptable → to achieve greater political feasibility. Remove/modify features that are most objectionable to its opponents or add features that opponents find attractive. Compromise often takes the form of negotiation: reach agreement through bargaining. Factors of influence: frequency with which the participants must deal with each other + political resources of participants. Remember that you deal with people (emotions, beliefs, etc.) + try to negotiate interests rather than positions. - Heresthetics → strategies that attempt to gain advantage through manipulation of the circumstances of political choice → through agenda or dimension of evaluation. Manipulation of agenda: changing the order/what in which policies are considered. Design proposals so they appeal to agenda setters or mobilize other actors to gain influence. Sophisticated voting = by not voting for your true preference you get a better outcome. Introduce a new consideration that splits the majority. - Rhetoric → use of persuasive language to frame issues in favorable ways. Most effective when you influence indirectly through public opinion (policy window). Emphasize very negative, but unlikely, consequences. Tell stories to communicate complicated ideas. Best way to appear honest is to be honest. Chapter 12 Implementation → many actors with sometimes conflicting interests which makes it more complex. Prerequisite → logic of a policy is a chain of hypotheses. A policy alternative is likely to be intrinsically unimplementable if you cannot specify a logical chain. Elements of a policy are the hypotheses linking policy to desired outcomes. Assembly metaphor → the more numerous, heterogeneous, and tightly linked the elements are that must be assembled, the greater is the implementation complexity. Tightly linked elements make it difficult to select/replace coupled elements independently + risk of overall failure because need for redesign when any one element fails. Roles in the implementation process (see figure 12.1) - Implementation managers → provide the detailed designs for implementation. A manager who views policy as undesirable is less likely to expend resources during the process. Solution: create new organizational units. Important: goal congruence at the organizational level + visible/personal responsibility + ability to assess the outcome immediately + available resources + legal authority + political support + skills. - Doers → provide any of the elements needed for the desired policy outcome. Often organizational members who directly provide services to clients (street-level bureaucrats). They actually implement almost all policies. Important resources: monetary, realistic time frame, staff to train frontline personnel, reliable information technology systems. Tactics to hinder implementation: tokenism (implementer bears burden of showing compliance was inadequate), delayed compliance (politically costly implementer), blatant resistance (rare). Legal authority of implementation manager is not enough for success. - Fixers → help gain elements that are being withheld; has specialized expertise. Boundary spanners facilitate communication between implementation managers and doers. Eyes and ears of the implementation manager/ designers/ analysts. Important: allies at the local level + progress reports/advisory bodies + unburdened by routine organizational responsibilities. Implementation analysis techniques - Forward mapping (table 12.1) → specification of the chain of behaviors that linka policy to desired outcomes. To anticipate problems likely to be encountered during implementation of already formulated policies. Need cleverness, courage, research. Dirt mindedness = what can go wrong + who has an incentive to make it go wrong. 1. Write the scenario → what, who, when, why. Quotes from interviews and noting past behaviors that are similar help. 2. Critique the scenario → is the scenario plausible? Consider motivations of actors! Can you counter noncompliance → positive/negative incentives. Think about what actors will oppose the policy and interfere. 3. Revise the scenario → strive for a plot that is plausible. If it still does lead to the desired outcome, then basis for a plan of implementation. - Backward mapping → generate policies with good prospects for successful implementation. Begin thinking about policies by looking at the behavior that you wish to change. Bottom-up approach to let people self-select. Uncertainty and error correction - Redundancy and slack → insurance device. Designing forms of redundancy into new policies makes them more feasible and robust. Useful in facilitating experimentation + reduction of uncertainty (easier to cope with unexpected loss of one supplier) + if supplementing initial allocation during implementation is difficult. - Designing in evaluation → learning and adjusting. Before/after comparisons take measures on variables of interest before and after the policy is implemented. Nonequivalent group comparisons take measurements of variable of interest for a group subjected to intervention and a group that is not. Important for evaluation: will results influence a future decision, skills, completed soon enough, results credible. Also: reporting requirements. - Facilitating termination → anticipate possibility of termination + strengthen bargaining position. Sunset provisions set expiration dates for policies. Most effective if coupled with evaluation requirements. Keep cost of termination to employees low → avoid designing permanent organizations + contracting out. Buy off the beneficiaries of the policy you hope to terminate + compensation. - Responding to heterogeneity → relevance of context. Not every situation is the same → design in flexibility and decentralization. 1. Bottom-up processes → allow self-selection: permits the participation of interest groups to prevent political attacks on the entire policy. Capacity building: facilitating improvements in the capabilities of local organizations → better able to initiate bottom-up policies. 2. Phased implementation → when there are limited resources. Select a representative set of sites in the first phase or picking sites where the conditions for success seem most favorable (if early failure will create political attack). Understanding the implications of repeated interaction Rational choice theory of institutions models social interactions as repeated games → insight into social norms, leadership, corporate culture, and policy design. - Social and organizational norms (figure 12.2) → create repeated game. Strategy: cooperate on the first play and continue as long as other player cooperated in previous round; if other player defects, then defect in all subsequent plays. α has to be smaller than 1/(1-δ) to reach an equilibrium. The more likely it is that interaction will continue, the stronger temptation for defection can be controlled. - Leadership and corporate culture → tit-for-tat strategy when one cooperates until you encounter a defection and from then play the strategy played by the other player in previous round. Problem: repeated games have infinite number of equilibria. Leadership to provide solutions → create focal points (attractive outcomes). Corporate culture = set of norms associated with the organization itself. Reputation! Externally imposed changes that forces organizations to violate corporate cultures may result in reductions in performance. Chapter 13 Lot of potential organizational forms; government delivery not necessary direct production, only some form of government provision. Neo-institutional economics (NIE) focuses on the specific nature of the transaction → useful in considering boundaries for organizations. Which organization will deliver the promised service product: provision of production? Difference public and private for-profit organizations is that public managers cannot retain any fiscal residual. Contracting out/outsourcing = delivery of public services through for-profit firms or private not-for-profit organizations. Mixed enterprises (public and private ownership), Social (ownership between for-profit and not-for-profit private organizations), Government sponsored (privileges for-profit owners). Public-private partnerships involves private entity that constructs a project in return for payments. Typically large, complex and unique projects → often capital intensive infrastructure projects. Fragmented ownership/property rights + partners with different and often conflicting goals + recipe for high transaction costs and opportunism. Address relative efficiency of organizational forms: transaction cost theory (Coase). Mainly concerned with the governance of contractual relations (that are almost never complete). Analysts should take into account transaction and production costs, both are social costs. Types of costs - Production costs → opportunity costs of real resources, actually used to produce something. Lowest in competitive environments free from market failures. In-house production: production at too low levels to be efficient. Large not-for-profit organizations may be able to achieve economies of scale. No min. costs that are technically feasible because of absence of competition, resulting in X-inefficiency. Also X-inefficiency because of inflexibility in the choice of factor inputs (civil service rules). Contracting out generally results in lower costs. Not with cost-plus contracts: these guarantee contractee a profit no matter how high the production costs. - Bargaining costs → costs directly in negotiating contract details, negotiating changes to the contract, monitoring, contract breaking mechanisms. Advantage not contracting out: distribution of costs can be resolved by the existing arrangements of hierarchical authority. - Opportunism costs → behavior by a party to a transaction designed to change the agreed terms of that transaction to be more in its favor → bad faith. More likely in contracting out because the question of who gets the rents is more relevant. Take advantage of imperfect monitoring + claim that behavior results from unexpected change in circumstances so they need additional payments, etc. Factors that determine the sum of bargaining and opportunism costs (table 13.1) - Task complexity → degree of difficulty in specifying and monitoring the terms and conditions of a transaction. Determines uncertainty + potential for info asymmetry. Complex tasks: uncertainty about nature/costs of the production process itself + more likely to be affected by shocks → more bargaining costs. Info asymmetry because it implies specialized knowledge whose characteristics are only known to contractees → transaction party can behave opportunistically. Often production externalities. - Contestability → contestable market when many suppliers would become available if price exceeds AC incurred by potential contract providers. Public agencies can reduce production costs by contracting out. Contestability when providers can switch production without sinking upfront costs. Low contestability: pricing above MC (bargaining cost), if they make profit then it is a social cost (paid by tax revenue) + risk of opportunism because supplier cannot be quickly replaced & contract breach externalities (core services). Contracting out when economy of scale + sunk costs → solve through exchange agreements + own the sunk costs assets. - Asset specificity → asset is specific if it makes a necessary contribution to production and has much lower value in alternative uses. High asset specificity raises the potential for opportunism + reduces contestability at the time of contract renewal + reduces contracting out + more monitoring. Useful to distinguish between ex ante and ex post mechanisms. Not-for profits provide public goods + contributors do not have the info to assess whether their contribution is actually used for production → principle-agent. Not allowed to make profit, but they can transfer/dissipate excess of revenue over costs. Advantages: voluntary contributions, flexibility. Problems: relative independence, contracting out can lead to change in strategies. More autonomous public organizations more focus on efficiency, managers more discretion. Flexibility in hiring/firing, more efficiency, higher-powered incentives (ex: bonuses). But weakens authority of government oversight mechanism + conflict other public goals. Public-private hybrid organizations often principal-principal problems + opportunism. Features of property rights to help guide consideration of ownership (table 13.2) - Ownership fragmentation → much fragmentation: transaction costs + costs of monitoring high + principal-principal problems. - Clarity of allocation of ownership rights → lack: opportunism because of the need to resolve ambiguities arising (incompleteness of contracts), often by private partner. - Cost of alienation → high when one has veto power over transactions + differentiated ownership rights (principal-principal bargaining). - Security from trespass→ ensures that rights holders can exercise them. Trespass if weak compliance norms, imperfect enforcement, costly self-protection. - Credibility of persistence → determines willingness for investing. Lack if the liability of private partner does not extend beyond assets of the hybrid. - Autonomy given to managers → increases efficiency + principal-agent problems. Example: Amsterdam South axis → great recession in 2008, banks (´too big to fail´) pulled out of the partnership. Project came to an immediate standstill. Building organizational capacity to monitor service quality may reduce opportunism, effective contracting out begins with adding capacity to central functions of public agencies. Chapter 15 Begin with self-analysis → linear writers should adopt nonlinear thinking strategies, while nonlinear thinkers should adopt linear writing strategies + analysts should simultaneously utilize linear and nonlinear modes when conducting policy analyses. Policy analysis is client driven → address the issue that the client poses + better to answer with uncertainty the question that was asked + good analysis does not suppress uncertainty. If your client asks the wrong question, you must fully explain why you think that. Reformulate expressions of symptoms/statements of alternatives into analytical frameworks. Analysis process: figure 15.1. Balance between problem and solution analysis to create credibility. Problem analysis 1. Understanding the problem - Assessing symptoms → clients specify problems in terms of undesirable symptoms. Assess them and provide an explanation of how they arise. Locate data that put the symptoms in quantitative perspective, become familiar with current public discussion + history of existing policies. - Framing the problem → there is a policy problem. Specification of the expected deviation between utility maximization by individuals and aggregate social welfare. Avoid reductionism, integrate other goals than efficiency. Is it a market or government failure? - Modeling the problem → develop models that relate the conditions of concern to variables that can be manipulated by public policy. 2. Choosing and explaining goals and constraints - Goal vagueness: goals as outputs of analysis → ask for goals before starting the analysis, because client may not have decided or is unwilling to reveal them. Always consider relevance of (aggregate) efficiency and equity. Present arguments for including/excluding a goal. Substantive (society cares about for their own sake) and Instrumental goals (increases achievement of substantive goals). Constraint set should include resources that are essential for maintaining current policy or implementing alternatives. - Clarifying trade-offs between goals → set of feasible policies determine possible trade-offs. Weights placed on goals are an output of policy analysis. - Clarifying distinction between goals and policies → distinction between values we seek to promote and alternatives/strategies for promoting them. Confusion because policies are often stated as goals. Formulate goals as abstractly as possible, and alternatives concretely (specific actions). Goals must be normative. Impact categories that are relevant for a goal may be varied. 3. Choosing a solution method (see figure 15.2) Program evaluation = assessment of an implemented policy (ex post analysis). Is connected with ex ante analysis, because use same goals + can provide information. - Cost-benefit analysis → efficiency only relevant goal. Reduce impacts of an alternative to a common unit of impact. Recommend when it has the largest aggregate net benefits. - Qualitative cost-benefit analysis → efficiency only, but not all impacts can be monetized. Make qualitative arguments about magnitude of the impacts. - Modified cost-benefit analysis → analysis almost never involves a single goal unless that goal is efficiency. Monetize efficiency and the other goal. Distributionally weighted CBA: single metric for ranking alternatives, but only achieved by claiming the equity and efficiency are commensurable. - Cost-effectiveness analysis: identifying technical efficiency → both efficiency and other goal can be quantified but the other goal cannot be monetized. 2 ways: fixed budget approach ( choose level of expenditures and find alternative that provides largest benefits) + fixed effectiveness approach (specify level of benefit and choose alternative that achieves this at lowest cost). Cannot tell whether a given alternative is worth doing (CBA can). - Multi-goal analysis → three or more goals are relevant or 1 of 2 goals cannot be quantified. Solution analysis Goals/alternatives matrix displays the impacts of alternatives relevant to goals (table 15.1). 1. Choosing impact categories for goals → thinks of all the possible impacts that might be relevant to the goals. Make sure there is a place to record every valued impact predicted for your alternatives. 2. Specifying policy alternatives → Look at existing policy proposals and current policy. You can use tinkering. Generic policy solutions good starting point. Almost never a perfect/dominant policy alternative. Do not contrast a preferred policy with bad alternatives. Ensure that alternatives are mutually exclusive. Alternatives should provide real choices, alternatives should be consistent with available resources. 3. Prediction in terms of goals and their impact categories → list as many different effects that the policy can have and value these effects of each alternative on every impact category. Then you will be able to compare them. Do not suppress uncertainty in predictions. Baseline scenario = most likely state of the world. When uncertainty requires more than 1 scenario, produce a goals/impact matrix for each scenario. 4. Valuing alternatives in terms of goals and their impact categories → a common metric for several impacts makes them directly comparable. Make impact categories as comparable as possible. Do not focus too much on easily measured impact categories. 5. Assessment: comparing alternatives across incommensurable goals → be overt about values in the final phase of assessment + be explicit about uncertainty. You can construct a number of scenarios that cover the probable range and choose the best alternative under each scenario. Or, conduct a best case, most likely case, and worst case assessment for alternatives with very uncertain outcomes. 6. Presenting recommendations → What do you believe your client should do? Why? How? Recommendations should follow from your assessment of the alternatives. Briefly summarize (dis)advantages of policy you recommend. Provide a clear set of instructions for action. Communicating analysis (table 15.5) 1. Structuring interaction → prepare full drafts of your analysis at regular intervals over the course of your project, clients can comment on these drafts. Decompose your analysis into component parts + make the presentation within the components clear and unambiguous. Crystallizes disagreement. 2. Keeping your client's attention → timelines most import elements, and imperfect analysis delivered before an important decision is always better than a perfect one delivered after the decision has been made. Executive summary is a concise statement of the most import elements including your recommendations. Last sentence of your first paragraph is recommendation, the rest is support of it. Table of contents makes sure you can see where your analysis is going . 3. Establishing credibility → make sure that you cite your sources completely and accurately + flag uncertainties and ambiguities, good explanation of your goals. Chapter 17 Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a technique for systematically assessing the efficiency impacts of policies. If efficiency is the dominant goal, you have adopt the policy that offers the largest net benefits, because it has the most potential to be Pareto improving. Meta-analysis identifies all relevant evaluations of each type of relevant program, assesses the validity of them, and combines results to obtain estimates of the likely impacts of the program. CBA based on Kaldor-Hicks criterion = policy should be adopted if those who will gain could fully compensate losers and still be better off. Problem: compares utility across individuals in terms of a common dollar measure, or money metric. Structure of a CBA: Specify current and alternative policies Starting point: clear statement of current policy → identify which elements are relevant for assessing alternatives + impacts of current policy may change over time + policy changes at superior levels of government may be relevant to specifying ´current policy´over time. Net benefits of CBA are incremental = based on differences in impacts relative to current policy that the alternative would produce. Specify whose costs and benefits count Determining standing means to specify whose costs and benefits count. National standing and subnational standing → important if policy impacts spill across subnational borders or if they involve fiscal transfers across jurisdictions. Determining societal membership may also require determining who located within a jurisdiction should have standing. Issues of standing often arise in assessing policies that affect addictive consumption. Catalogue relevant impacts Use of resources (costs) to produce impacts (benefits) → cataloguing sets out the scorecard. Specify appropriate units to facilitate prediction and monetization. Impacts and costs are relevant when they are likely to affect net benefits/costs. Predict impacts over the time horizon of policies Determining the relevant time horizon → identify a realistic period over which the policy is being assessed. Terminal/scrap value is specified for the final year of the project. Sources of evidence for prediction → regression discontinuity design (study taking advantage of natural experiments) + difference-in-differences design (changes in outcomes can be compared to changes in outcomes for the constructed comparison group). Change in effective prices → base predictions on elasticities (if not available, find most similar elasticity). No quantitative evidence → expert opinions (Delphi method for combining expert opinions). Point estimates are the particular values of impacts viewed as most likely. Provide standard errors for point estimates, as no prediction is certain! Monetize all impacts Valuing inputs: opportunity costs → the opportunity cost of a policy is the value of the required resources in their best alternative uses. Important: the nature of the market for a resource. With no market failure and a flat supply schedule, opportunity costs are equal to the expenditures on the resources. When there are failures, you need to account for social surplus changes. Reservation wage = minimum wage at which one will offer labor. Opportunity cost = expenditures on the facor minus gains in social surplus occuring in the factor market. Valuing impacts: willingness to pay/accept → WTP = sum of max amounts that people would be wtp to obtain the increases in consumption of the good. WTA = sum of min amount people would be wta as compensation for the decreases in consumption of the good. Can differ substantially when the good does not have close substitutes. Use changes in consumer surplus. - Constructed markets → market for a good does not exist, but demand schedule can be estimated. Interpret constructed demand schedule as the marginal valuation schedule for the good, which provides a basis for valuing changes in prices/quantities - Hedonic price models → levels of non-marketed goods sometimes affect the prices of goods that are traded in markets (ex: housing market). Identify independent contribution of specific characteristics on price → hedonic price model. Need data! - Stated preferences → contingent valuation surveys for estimating the benefits of public goods (ask how much wtp to obtain them). But problems of survey research + may not treat hypothetical choice as an economic decision and ignore budget constraints, to gain a warm glow + respondents may answer strategically. The travel cost method → survey people about their actual behavior: estimation of the value of recreation sites from people´s use patterns. - Shadow prices → marginal valuations of impacts not revealed in the ´light´ of markets, because some types of policy impacts commonly arise. Value of statistical life (VSL) depends on income and base mortality risk. Cost of crime differs with bottom-up and stated preference methods. Marginal excess tax burden (METB) is the ratio of additional costs of taxation to the amount of revenue collected. Take account of general inflation when using an old shadow price. Discount costs and benefits to obtain present values If present value of receiving $100 next year is $90, then this $90 is the future payment discounted back to the present. Present value of consumption is the highest level of consumption that can be obtained in the present period. CN/(1+r)^N-1 Discounting makes costs/benefits accruing at different times commensurate so that they can be summed to obtain present values. Figure 17.3: production possibility frontier = locus of combinations of production on the curve connecting X1 and X2. Each additional unit of consumption in period 1 costs (1+r) units of consumption in period 2; the other way around 1/(1+r). Most favorable consumption possibility frontier is when the discount rate line is just tangent to the production possibility frontier. Most desirable consumption opportunity is at the highest indifference curve. With CBA: (Bt - Ct)/(1+d)^t-1, where d is the social discount rate (SDR). Marginal rate of pure time preference = rate at which consumers are willing to trade between marginal current and marginal future consumption. Marginal rate of return on private investment = rate at which the private economy transforms marginal current consumption into marginal future consumption. In perfect capital markets, the SDR equals the market rate of interest; but more complicated. People have finite lives, so not always take into account consumption possibilities of future generations + taxes and other distortions lead to differences in future/current consumption. Shadow price of capital approach allows for financing at the expense of both consumption and private investment. Problem: rarely enough information → choose a particular value of SDR, but: MR of pure time preference or return on private investment? Often gap between the two. Solution: a range of discount rates, report the largest SDR that yields positive net benefits, use the same SDR for all projects. Compute the present value of net benefits Present value of net benefits (NPV) → discount benefits and costs at the mid-year for years 1 … N-1. Ex: table 17.1. C0 = immediate cost; n = year; N = subsequent years; Bn = benefits of year n, Cn = costs of year n, and Sn = scrap value of freed-up resources of year n. Decide if you work with either real (strips out the effect of inflation) or nominal dollars. Nominal interest rates are directly observable in the marketplace; real interest rates not. Nominal: correct for inflation rate i. Real discount rate d = (r-i)/(1+i); when inflation is zero, this coincides with nominal discount rate r. i i s the expected rate of inflation. You cannot directly compare alternatives with different time horizons. If you want to compare them, one must convert each alternative to a stream of constant net benefits over its time horizon by dividing by the annuity factor =(1-(1+d)^-N)/d d i s discount rate (used across alternatives) and N is the time horizon (specific to each alternative). - FORMULA NPV Perform sensitivity analysis Each of the previous steps requires assumptions. 2 Types of analysis: how sensitive are the calculated NPVs for these assumptions?, how sensitive are the recommendations for these assumptions? Calculate average, worse and best case scenarios. Partial sensitivity analysis → systematically varying the value of a point estimate to assess how such variation affects net benefits. Partial because CBAs involve quite a number of uncertain parameters. Ex: investigating the impact of alternative values of the SDR on predicted net benefits → if the sign of net benefits does not change over the plausible range of the SDR, then it does not make a major difference. Some potential impact cannot be monetized → use breakeven value: how large do the excluded benefits have to be to produce positive net benefits for the policy change? Advantage: focus on particular assumption. Problem: not taking account of other uncertainties. Monte carlo simulation → 4 steps: specify a probability distribution for each uncertain parameter; randomly draw values from each distribution to calculate a predicted net benefit; repeat second step many times; present/analyze resulting distribution of net benefits. Specified distribution can be normal, uniform, or triangular. Reporting the standard deviation and the percent of trials providing net benefits conveys the degree of uncertainty. Recommendation Choose the combination of policies that maximizes net benefits. Problems: - Physical and budgetary constraints → when all policies are mutually exclusive, maximize efficiency by choosing the one with the largest positive net benefits. Avoid using benefit-cost ratios when comparing mutually exclusive alternatives. When combining projects they can be synergistic (together more worth than individually) or interfere with each other. There are also often budget constraints! - Distributional constraints → Kaldor-Hicks criterion does not require that people actually be compensated for the cost that they bear. Not convincing for policies that impose high costs on small groups → spread costs more evenly/provide direct compensation. Other solution: distributional constraints, which introduces values beyond efficiency → cost/benefit disaggregated for ´relevant´ groups. Valuable in anticipating political opposition + if policy needs to be mandatory. - Analytical Honesty → CBA should be well documented (use of appendices) + CBA should make the degree of certainty about the predicted net benefits clear. Chapter 18 PASA = public agency strategic analysis. Enables agencies to use available resources more effectively + reallocate resources among their programs to increase the social value they create + preserve/enhance their value as organizational resources for implementing policies. Goal → maximizing instrumental value of an agency as an organizational resource. You also have strategic analysis (more private). Differences in maximizing private rents or social value + legal and political environments. PASA focuses on alternative strategies for developing/using organizational resources. Creating public value → less economic, multifaceted, distributional impact relevant. Assesses both the external and internal resources of an agency. Political influence more central role in the external environments of agencies than with firms. Agencies are under influence of external forces (figure 18.1): lack of fit between agency resources and constraints imposed by external environment causes strategic failure. - Supplier bargaining power → public agency suppliers have bargaining power to their advantage. Power in the sense of economic (public agencies purchase most inputs from profit-maximizing supplier markets) and political dimensions. Non-monetized inputs are more common in public agency context, so bargaining more complex (not just about price and quality). Reduce bargaining power of suppliers → centralize purchasing across agencies (but then purchasing less flexible) Increase social value when good use of bargaining power ensures the lowest price. - Threat of entrants/substitutes barriers → government can anticipate conventional entry, but not radical technologically-based substitution threats. These bypass an agency through ´self-service´. With the advent of new cost-lowering technology, a threat of entry becomes real. Anticipating substitution threats helps with deciding whether to fight, flee, or adopt other strategy. - Purchaser/user bargaining power → 2 types of customers in the public sector: those who use the product, those who make the actual purchase decision. Most extreme form of bifurcation if users of the service do not participate in the purchase decision at all (ex: prison inmates). In this case, purchasers important. Purchasers have different interests than users. Assessment of bargaining power of purchaser complex when: multiple purchasers, differing demands, differing demand elasticities, political actors may be interested. Agents have stronger bargaining power when concentrated and less information asymmetry. Non-paying users: lobbying. Organizing costs lowers bargaining power of individual users. - Extent of actual competition or the threat of contestability → with natural monopolies, issue of the contestability of the monopoly. If agency prices are forced to approximate the MC of delivery, or technological change that erodes entry barriers, or broader socioeconomic change that alters demand, then more competition. - Political influence → 2 factors determine political influence force: institutional structure surrounding the agency´s establishment (formal legal and administrative structure) + degree to which these formal barriers are permeable in practice. Politically salient program outputs tend to attract attention that undercuts insulation + high degree of complexity tends to discourage political influencers. Political influence can directly affect level of competition of contestability. Dominant focus on rent extraction of private firms generally conflicts with the social value perspective. Internal analysis of public organizations → the value creation process can often be analyzed by thinking of it as a chain of steps (involve value chains), when the production process has a clear temporal sequencing of activities (inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics). Otherwise: modular assembly process solutions can be built from standard analytic components) or platform production process (agency at the nexus of an exchange process where it acts as an intermediary). First way of assessing value creation in public agency → focus on potential for cost reduction, but holding current level of output constant. Usually assessable, but reductionist. Reconfiguring (or eliminating) the current activity steps (business process reengineering). Second way → observe social benefits changes while holding cost constant. Third way → assess value creation within each agency program, holding neither costs nor outputs constant. Apply cost-benefit analysis. Agency autonomy is a function of the combined absence of policy and fiscal constraints. Assessment of current constraints helps determine the feasible alternatives for changing the value chain, anticipating changes helps identify feasible alternatives in the future. Lecture 3 Milton Friedman: market failure is no justification for government to step in because government failure exists too. Examples of other ways: tipping, rest facilities. Remember the contract curve: all points on it are pareto efficient. But which one is the best? This depends on your values → a matter of equity. How to steer this? → influence initial endowment points (decisive for where you end up on the contract curve) with incentives or use other policy instruments. 2 Theorems of welfare economics 1. Under certain conditions, any competitive equilibrium leads to a Pareto efficient allocation → perfect markets are Pareto efficient. 2. Under certain conditions, any Pareto efficient allocation can via public policy be attained by a competitive equilibrium → you can shift from one point to another via lump sum redistribution of initial endowments. Institutions (formal + informal): questions of compliance, legitimacy, justice. Lecture 6 Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is grounded in consequentialism (intentions, motivations are not interesting) → normative ethics. Steps CBA 1. Problem analysis → what is the problem? Who? In what extent? 2. Reference case → world without the project 3. Project alternative → world with a project 4. Estimating quantitative effects → financial effects, effects which make people happy or annoyed → positive & negative effects 5. Converting effects into monetary units Advantages of CBA - CBA provides in order of magnitude insight in welfare effects MCA is without costs - Forces to make lines of reasoning objective Politician forced to; expected effects → prove less subjective fantasy - Optimization of the project → after you see the CBA you can optimize + in advance: in the planning process more attention to costs and benefits of the project. Improved decision making: bullshit detector - Gives a warning signal if costs of a project are enormous Disadvantages - CBA cannot include all effects → image, knowledge developed during construction. - Effects that are easy to monetize will dominate the CBA Ex: how much is a life worth? (unethical?) - Uncertainty, lot of assumptions - Some people assign too much/too little value to the CBA - Not aware of limitations, and those who are aware will use CBA strategically How do politicians use research - Instrumental → direct and immediate implementation of recommendations always decide in line with the CBA - Conceptual → use of study for general enlightenment, change way of thinking CBA can change way of thinking towards a project - Opportunistic → use of study as political ammunition If CBA supports view I use, otherwise I don´t - Symbolic → use of study to make decision and politician look more rational CBA is a ´rational ritual´. The decisions don´t change. Lecture 8 Types of sources for your paper: 1. Systematic reviews of research 2. Scholarly books/articles 3. Organizational sources 4. Governmental sources 5. Popular media Chapter 18 - standard narrative: 1. Bureaucracy (hierarchy) → rules (deontology), strictly guided by political decisions. 2. NPM (new public management) → results (consequentialism), efficiency prime value, ´steering but not rowing´. 3. PVM (public value management) → public value(s) (pragmatism), government cannot be modelled on the market. Public value mapping (figure 8.1). Public value failure = neiter market/public sector provides goods/services required to achieve public values. Chapter 19: give useful advice, do no harm & improve society, human dignity, and freedom.