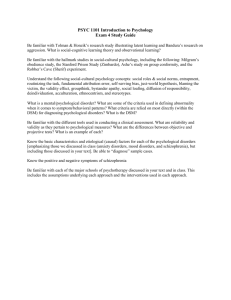

Defining Psychological Disorders: Dysfunction, Distress, Culture

advertisement