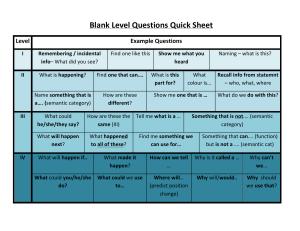

6. INTRALINGUISTIC RELATIONS OF WORDS. TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS 1 2 Intralinguistic Relations of Words. 1.1. Syntagmatic Relations. 1.2. Paradigmatic Relations. Basic Types of Semantic Relations. 2.1. Proximity. 2.2. Equivalence. 2.3. Inclusion. Hyponymic Structures. 2.4. Opposition. KEY TERMS Syntagmatic relations, paradigmatic relations, free (denominative) meanings, semantic proximity, semantic equivalence, inclusion, hyponyms, hyperonym, semantic opposition, polar opposition, relative opposition. 1. INTRALINGUISTIC RELATIONS OF WORDS The principles which determine the internal structure of the language were derived by Ferdinand de Saussure from two basic notions which have become traditional in linguistics. Word-meaning can be perceived through intralinguistic relations that exist between words. Intralinguistic relations of words are basically of two types: syntagmatic and paradigmatic. 1.1. SYNTAGMATIC RELATIONS Syntagmatic relations are the relationships that a linguistic unit has with other units in the stretch of speech in which it occurs. Syntagmatic relations define the meaning the word possesses when it is used in combination with other words, for example, the meaning of the verb to get can be understood from the following contexts: He got a letter (to receive); He got tired (to become); He got to London (to arrive); He could not get the piano through the door (to move smth. to or from a position or place). So, syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words. Most words come to the fore only when the word is used in certain contexts. This is true of all polysemantic words. The adjective yellow, for example, when used in isolation is understood to denote a certain colour, whereas other meanings of this word, for instance, ‘envious’, ‘suspicious’ or ‘sensational’, ‘corrupt’ are perceived only in certain contexts: a yellow look, the yellow press, etc. Context is the minimal stretch of speech determining each individual meaning of the word. The meaning or meanings representative of the semantic structure of the word and least dependent on context are usually described as free or denominative meanings. Thus, we assume that the meaning ‘a piece of furniture’ is the denominative meaning of the word table, the meaning ‘construct, produce’ is the free or denominative meaning of the verb make. 1.2. PARADIGMATIC RELATIONS Paradigmatic relations are the relations that a linguistic unit has with units by which it may be replaced. Paradigmatic relations exist between words which make up one of the subgroups of vocabulary units: sets of synonyms, pairs of antonyms, lexico-semantic groups, etc. Paradigmatic relations define the meaning the word possesses through its interrelations with other members of the subgroup in question. For instance, the meaning of the verb to get can be fully understood in comparison with other units of the synonymic set: to obtain, to receive, to gain, to acquire, etc (see Diagram 11. Diagram 11. Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations of words Syntagmatic relations He got a letter. I received an e-mail She obtained a note Paradigmatic relations Paradigmatic relations are associative relationships between words. The distinction between syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations is conventionally indicated by horizontal and vertical presentation. 2. BASIC TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS There are four basic types of semantic relations: proximity, equivalence, inclusion and opposition. 2.1. PROXIMITY Words very seldom are the same semantically, i.e. they are not identical in meaning and show a certain semantic difference as well as similarity. Meaning similarity is seldom complete and is nearly always partial which makes it possible to speak about the semantic proximity of words and, in general, about the relations of semantic proximity. Let us compare the meanings of some adjectives, which form a lexico-semantic group (see Table 5). Table 5. Adjectives used for describing a female appearance from the point of view of similarity and dissimilarity in their content side Beautiful Extremely good-looking, much more so than most women Pretty Good-looking in an ordinary way but not really beautiful or sexually exciting Attractive Good-looking, especially in a way that makes you feel sexually interested Striking Very attractive, especially because a woman has a particular feature, such as hair or eyes, that is beautiful and unusual Handsome Good-looking in an unusual way, especially because a woman is tall or strong or looks as if she has a strong character We can see that the adjectives are characterized by certain features of semantic dissimilarity which shows that they are not absolutely identical in meaning. Semantic proximity implies that two (or more) words however different may enter the semantic relations of proximity if they share certain semantic features, for example, the words red and green share the semantic features of ‘colour’, ‘basic or rainbow colour’, ‘complementary colour, etc. The words may be graded in semantic proximity. A higher degree of semantic proximity helps to single out synonyms while a lower degree of proximity provides for a description of boarder and less homogeneous semantic groups. For example, the degree of proximity will be much lower in the words red and green which share the semantic feature of ‘colour’ than in red and scarlet or green and emerald. The words table and chair share the semantic features of ‘thingness’, ‘object’, ‘piece of furniture’ that form a good basis for grouping them together with other nouns denoting ‘pieces of furniture’. 2.2. EQUIVALENCE Semantic equivalence implies full similarity of meaning of two or more language units. Being an extreme case of semantic proximity it is qualitatively different from all other cases suggesting the existence of units different in form but having identical meaning, i.e. one and the same content side. Semantic equivalence is very seldom observed in words and is claimed to be much oftener encountered in case of sentences, for instance, the phrase John is taller than Bill may be considered equivalent to the phrase Bill is shorter than John, and the phrase She lives in Paris is semantically equivalent to She lives in the capital of France. Semantic equivalence in words is highly unstable, it tends to turn into the relations of semantic proximity. This pronounced tendency to semantic differentiation may be viewed as a realization of the economy principle in the language system which ‘does not need’ words different in form and absolutely similar in meaning. 2.3. INCLUSION. HYPONYMIC STRUCTURE Another type of semantic relations is the relationship of inclusion which exists between two words if the meaning of one word contains the semantic features constituting the meaning of the other word. The semantic relations of inclusion are called hyponymic relations. For example, vehicle includes car, bus, taxi, tram and flower includes daffodil, carnation, snowdrop, lily. The hyponymic relations may be viewed as the hierarchical relationships between the meaning of the general and the individual terms. The general term – vehicle, tree, animal – is referred to as the classifier or the hyperonym. The specific term is called the hyponym (car, tram, train; oak, ash, birch; cat, tiger, horse). The more specific term (the hyponym) is included in the more general term (the hyperonym), for example, the classifier move and members of the group – walk, run, saunter. The individual terms contain the meaning of the general term in addition to their individual meanings which distinguish them from each other. It is important to note that in hyponymic structure certain words may be both classifiers (hyperonyms) and members of the group (hyponyms) (see Diagram 12). Diagram 12. Hyponymic structure of words describing plants Plant Grass bush pine white pine shrub куст tree oak ash flower maple yellow pine The diagram demonstrates that the words tree and pine are both hyperonyms (the classifiers) and hyponyms (the members of the group). 2.4. OPPOSITION The contrast of semantic features helps to establish the semantic relations of opposition. For instance, the meaning of the word black is contrasted to that of the word white. The relations of opposition imply the exclusion of the meaning of one word by another, which, in fact, implies that the referential areas of the two (or more) words are opposed. Thus, black is opposed to white but it is not opposed to either red or yellow. In the latter case we can speak about contrast of meaning, but not the semantic relations of opposition. There are two types of relations of semantic opposition: 1) Polar oppositions are those which are based on the semantic feature uniting two linguistic units by antonymous relations, for example, rich – poor, dead – alive, young – old. 2) Relative oppositions imply that there are several semantic features on which the opposition rests. The verb to leave means ‘to go away from’ and its opposite, the verb to arrive denotes ‘to reach a place, esp. at the end of a journey’. It is quite obvious that the verb to leave implies certain finality and movement in the opposite direction from the place specified. The verb to arrive lays special emphasis semantically on ‘reaching something’, i.e. attaining a point which is set as an aim and implies effort in achieving the goal. Thus, it is not just one semantic feature the presence of which in one case accounts for the polarity of meaning, but a whole system of semantic features which underlies the opposition of two words in the semantic aspect. QUESTIONS 1. What are the basic types of intralinguistic relations of words? 2. What do syntagmatic relations mean? 3. What relations are called paradigmatic? 4. How do most polysemantic words come to the fore? 5. Which meanings are called free or denominative? 6. What are the main types of semantic relations? 7. What does semantic proximity imply? What are the two extreme cases of semantic proximity? 8. What is semantic equivalence? Is semantic equivalence a stable type of semantic relations? 9. What is meant by inclusion as a type of semantic relations? 10.What is the other linguistic term used to denote semantic relations of inclusion? 11.What do the terms hyponym and hyperonym mean? 12.What is opposition as a type of semantic relations? 13.What types of semantic opposition can be singled out? REFERENCES: 1. Гинзбург Р.З. Лексикология английского языка. М. Высшая школа, 1979. – С.- 47-55. 2. Зыкова И.В. Практический курс английской лексикологии. М.: Академия, 2006. – С. – 39-43.