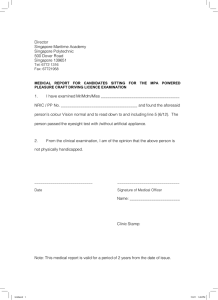

Keep an open mind on history of Operation Coldstore Vernon Lee Senior Editor Yahoo News Singapore 10 April 2018 A set of books that run counter to the dominant national narrative on Operation Coldstore. (Left to right): “The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye” by Sonny Liew, “The 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore – Commemorating 50 Years”, “Comet in Our Sky” – a collection of essays on secretarygeneral of Barisan Sosialis Lim Chin Siong, and “Living In A Time of Deception” by ex-Coldstore detainee Poh Soo KaiLess The recent media spotlight on Operation Coldstore has shown that one of the darkest chapters in Singapore’s history remains a sensitive topic to broach more than 55 years after it took place. Coldstore, carried out by the police and Special Branch officers in the wee hours of 2 February 1963, was at the centre of a six-hour long exchange between Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam and historian Thum Ping Tjin at the hearing of the Select Committee of Deliberate Online Falsehoods in Parliament House on 29 March. Central to the sometimes terse exchange was Thum’s assertion that Coldstore, which saw the arrests of more than 100 people including leaders of opposition party Barisan Sosialis, was motivated by political considerations rather than a justifiable security operation to thwart a conspiracy by the communists to seize power in Singapore. Thum said in his written submission to the committee, “Beginning with Operation Coldstore in 1963, politicians have told Singaporeans that people were being detained without trial on national security grounds due to involvement with radical communist conspiracies to subvert the state. Declassified documents have proven this to be a lie.” But Shanmugam slammed Thum for his work into Coldstore at the hearing, pointing out for instance that his research ignored critical circumstances leading to the arrests and accounts given by leaders of Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), such as then Secretary-General Chin Peng. “You ignore and suppress what is inconvenient…I’m suggesting to you, based on what you have said to us, what we have seen is not scholarship, but sophistry,” said Shanmugam. The exchange and the discussions that followed underscored Coldstore as Singapore’s most historically sensitive event. It was just one of many occasions over the years that government leaders have sought to debunk the “revisionist” version of Coldstore. Any accounts that run counter to the dominant national narrative – specifically by those deemed as “revisionist historians” – could undermine the standing of the leaders behind the decision to execute Coldstore and call into question the political legitimacy of the People’s Action Party (PAP) government back then. In late 2014, there was a flurry of statements from top government leaders and officials who spoke at length about the communist threat, and related public education activities were also held. At the launch of the reprint of the “Battle for Merger” book – a compilation of talks delivered by Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew in late 1961 – Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean spoke about the critical steps taken by the then authorities to crush the communist movement. Teo said, “The wrong decision, and it would have gone the other way and Singapore would have turned out very differently.” An accompanying exhibition on the same topic was held at the National Library. After attending the exhibition, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in a post on his Facebook page, “Their first person (CPM leaders) accounts, like the British documents (UK government archives), confirm the extent of the Communist united front in Singapore, and leave no doubt that the Barisan was formed at the instigation of the CPM, and that Lim Chin Siong was a Communist cadre.” Give greater access to Coldstore secret files The historians, however, are still divided on many key issues surrounding Coldstore, particularly on the arrests of senior leaders of Barisan Sosialis, a party formed by a breakaway faction of the PAP. Was the security sweep partly a calculated move to deny the Barisan Sosialis a chance to secure power through the ballot box in 1963? Were Lim Chin Siong, secretary-general of Barisan Sosialis and co-founder of the PAP, and his party members avowed communists who were conspiring as part of the Communist united front to overthrow the government through an armed struggle if necessary? Was the CPM already a spent force years before Coldstore or did it have considerable sway on Singapore politics and trade unions even after it was defeated during the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960)? Given that Coldstore will continue to be a subject of intense debate and speculation in the years to come, there should be new and bold approaches to shed further insight into the event so that Singaporeans can make an informed choice on which competing versions of history to believe in. The most important step that should be undertaken is for the government to open the files on the event archived in the Internal Security Department. Currently, only a few academics have gained access to the files including Associate Professor Kumar Ramakrishna of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, who has written several articles published in The Straits Times and other media outlets to reject Thum’s findings. One argument against allowing greater access to the files is that it would lead to cherrypicking of evidence and biased interpretation by some historians to reinforce a prior narrative on Coldstore. Others, however, brush aside such concerns, saying that transparency in the field of historical research is par for the course. Thum said in a post on Facebook, “As a historian, I would be happy to modify my arguments based upon the government archives. Its unwillingness to do so weakens its own case. Please declassify the archives and let us know the truth once and for all. I would be delighted by this even if it proved me wrong. The truth is what matters.” Another area that can help facilitate wider discussion is for the relevant authorities overseeing the creative fields, such as the Info-communications Media Authority of Singapore and the National Arts Council (NAC), to loosen the regulations that are curbing works perceived to be inimical to the established narrative. Filmmaker Tan Pin Pin’s “To Singapore With Love” film, about Singapore’s political exiles including those who had escaped from the Coldstore dragnet, was not given any film rating by then Media Development Authority when it was released in 2013. Rejecting Tan’s appeal for classification, the Film Appeal Committee said “the film would pose a serious risk to Singapore’s national security by condoning the use of violence and subversion as a means to achieve political ends in Singapore.” Nonetheless, the authorities have adopted a more accommodating approach towards “revisionist” books that are focused primarily or partly on Coldstore. For example, books like “The 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore – Commemorating 50 Years”, which compiles the writings of academics and former Coldstore detainees, “Living In A Time of Deception” by Coldstore detainee Poh Soo Kai, and the award-winning “The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye” by comic artist Sonny Liew, probably would have been banned during the Lee Kuan Yew era, but are available for sale in the bookshops. This is a step in the right direction and authors who are looking to mine Coldstore for their future works should be allowed to have unfettered space to release them so long as they do not breach the relevant laws. Singapore’s history Secondary Two textbook One acceptable version of history? In the area of secondary school education, students should be exposed to the works of historians on Coldstore beyond what is described in the approved history textbook. Being able to read widely on the different historical perspectives is a step towards the broader goal by the education ministry to encourage students to develop critical thinking skills. There should be open and rigorous debate in the classroom on sensitive topics, be it on Coldstore, the move towards merger with Malaya, and Operation Spectrum, otherwise known as the 1987 “Marxist Conspiracy”, which saw the arrest of 22 people for allegedly being involved in subversive activities. In the secondary two history textbook, there were mentions on Coldstore and several of the detainees including Lim and his fellow Barisan Sosialis leader Fong Swee Suan. Lim was arrested during “an anti-communist raid” and was detained for his “suspected links” with the CPM, according to the textbook. A separate section described those who were detained during Coldstore were “believed to be under communist influence” and that they were “accused of trying to sabotage the formation of Malaysia and planning to launch an uprising in Singapore.” Shortly after the NAC withdrew its grant for “Charlie Chan”, which drew inspiration partly from Coldstore, a teacher spoke about the saga during a talk organised by Liew’s publisher Epigram Books in 2015. He said that the NAC was aware that while its action would create a “Barbara Streisand effect” and boost sales of the book, its broader intention was to signal to educators that a line had been drawn on what was the acceptable version of history. Rival proponents of the history of Coldstore should be able to hold public debates in places such as schools, institutes of higher learning and libraries without having to navigate through red tape or fear of repercussion. The historians whose research into the event converged with the government’s account should go beyond publishing their views in the mainstream media and academic journals and challenge their “revisionist” peers such as Thum and Hong Lysa in front of an audience, with both sides subject to scrutiny from members of the academia and the public. The two sides should be wary of taking intransigent positions on Coldstore when new evidence is available, and bear this advice from Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan who said, “We can learn from history, but we can also deceive ourselves when we selectively take evidence from the past to justify what we have already made up our minds to do.” Finally, the validity of Coldstore research should not be conditioned upon the imprimatur of the present-day authorities. They must step aside from sanctifying what ought to be the “truthful” version of history and leave it to the historians to conduct research and publish works that are subject to systematic reviews by their peers in Singapore and overseas. The first-hand accounts of the key players behind Coldstore and the detainees – who are either dead, exiled or living their twilight years in Singapore and elsewhere – should assume primacy over the views of the authorities for the purpose of research. Singapore’s modern history is not a simple, linear progression of the dominant narrative. It requires nuanced interpretations at times of crucial junctions such as Coldstore based on dispassionate analysis of a myriad of sources. To let a single narrative set the course of historical research and mainstream education is to eviscerate a discourse on an event central to understanding the country’s tumultuous path towards nationhood.